Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Barker

Hochgeladen von

Ronz de BorjaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Barker

Hochgeladen von

Ronz de BorjaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Sierra Nevada College

IMPROVING HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS PARTICIPATION

IN PHYSICAL EDUCATION

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Master of Arts in Teaching

by

Billy H. Barker

Dr. Marsha Kobre Anderson/Thesis Advisor

May 2013

We recommend that the thesis by Billy H. Barker

prepared under our supervision be accepted in

partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

MASTER of ARTS in TEACHING

______________________________________________

Marsha Kobre Anderson, Ph.D., Thesis Advisor

_______________________________________________

Tommy Krier, M.S., Committee Member

________________________________________________

Liz Castoe, M.Ed., Committee Member

May 2013

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

List of Tables .................................................................................................................... v

Abstract ............................................................................................................................. vi

Acknowledgments............................................................................................................. vii

Chapter I Introduction to the Study ..................................................................................

Purpose Statement .................................................................................................

Research Questions ...............................................................................................

Importance of the Study ........................................................................................

1

2

2

3

Chapter II Review of the Literature .................................................................................. 4

Student Motivation During Physical Education ................................................... 4

Gender Differences in Physical Education Participation ...................................... 11

The Relationship Between Physical Activity and Health ..................................... 14

Chapter III Methodology .................................................................................................. 20

School Context ...................................................................................................... 21

Participants ............................................................................................................ 21

Classroom Setting ................................................................................................. 22

Data Collection and Analysis................................................................................ 22

Procedural Plan ..................................................................................................... 23

Chapter IV Results ............................................................................................................ 25

Survey ................................................................................................................... 25

Small Group Interviews ........................................................................................ 28

Chapter V Discussion, Conclusion, and Implications ...................................................... 32

Discussion and Conclusion ................................................................................... 32

Implications........................................................................................................... 34

Reflection .............................................................................................................. 35

References ......................................................................................................................... 36

iii

Appendix A: Letter of Informed Consent ......................................................................... 39

Appendix B: Survey and Interview Questions.................................................................. 43

iv

LIST OF TABLES

Page

Table 1

Student Survey Results by Variable and Gender ...................................... 27

Table 2

Participation in Activities Before and After Implementation

of Student Choice...................................................................................... 30

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this action research project was to explore how student choice in activity

during physical education affects student motivation to participate in daily physical

activity. I administered a survey to identify student attitudes towards physical education.

This survey also identified preferences for activities by gender. Interviews were

conducted with students to clarify questions unanswered by the survey. Survey data

indicated that both male and female students enjoyed the choices being offered during

PE. In addition, data revealed students had a positive attitude toward motivation during

PE; however, interviews suggested otherwise. A majority of females would like samegender classes, while males expressed a neutral attitude. Interviews confirmed much of

the data reported during the survey.

vi

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Dr. Marsha Kobre Andersonwith her insight and

knowledge, she made finishing this thesis possible.

I would also like to thank Tommy Krier and Liz Castoe for being my committee

members and being there for me when I needed them.

Most of all, I would like to thank my wonderful wife and sister-in-law for all of

their help, support, and patience through this entire process.

vii

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY

The participation rate of children in physical activity is declining drastically

among adolescents in America. Students self-motivation during Physical Education (PE)

class is declining, leading to heightened rates of obesity. The obesity rate for students

aged 12-19 is 18%. Johnston, Delva, and OMalley (2007) reported that between the

grades of 8-12, participation rates in PE were on the decline. Why are more students not

motivated to participate in PE?

PE classes help children develop healthy lifestyles, encouraging students to eat

healthy and get the recommended 60 minutes of physical activity daily suggested by the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012). If students do not have selfmotivation to participate in physical activity while they are young and in school, how will

they be self-motivated outside of high school? Being physically active has the ability to

keep down heart disease and high blood pressure. Beets and Pitetti (2005) reported that

PE promotes muscle training and healthy weight management. According to the Physical

Activity Council (2012), a recent study found an adult who participated in PE at school is

four times more likely to participate in a racquet sport and about three times more likely

to participate in a team sport, outdoor activity, or golf.

High school students in Nevada, where I teach PE, are required to earn a

minimum of two high school PE credits in order to graduate. Many students who attend

PE struggle to make passing grades due to their lack of self-motivation to participate

actively during class. Participation in PE includes the following: (a) attendance at school,

(b) dressing out (changing into a PE uniform), (c) wearing tennis shoes, and (d) active

movement. As a high school physical education teacher, I am concerned about my

students lack of participation and unwillingness to be physically active inside and

outside of school. Currently, 30% of my students are at risk of not passing PE. I do not

believe this is due to my ability to teach or encourage, but it is directly linked to their

self-motivation, or lack thereof. PE is used as a way to teach children about sports, but

what if the current students want something more from PE? What choices can I provide

to students, and how can I help them motivate themselves?

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this action research study was to explore why high school students

are unwilling and not self-motivated to participate in physical activity during PE class. In

addition, this research will identify physical activities that are preferred by high school

students.

Research Questions

This action research study was guided by the following questions:

1. What is causing students unwillingness and lack of motivation to participate in

PE class?

2. What activities, if any, would motivate students to be more physically active

during class?

3. What social factors influence high school students desire to participate or not

participate during PE class?

Importance of the Study

The current problem in my PE classes is the lack of participation and selfmotivation by high school students. This problem is worth researching because obesity

and inactivity are on the rise, especially among young people. I want to do my part to

help students realize the importance of physical activity. I know that self-motivation in

PE is directly linked to self-motivation in other classes. As a result of this study, I am

hoping to discover what is making my students unwilling to participate. It is important to

uncover what activities I could provide that would encourage students to participate on a

regular basis.

This research may aid other PE teachers in making adjustments to their PE

programs that would encourage students to self-motivate and participate in PE. Through

participation in this research, students may find an activity with which they can have

success. If students can find success with one physical activity, it is possible that students

will participate in the activity outside of school or throughout adulthood.

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

The review of literature examined the research conducted on motivation and

participation of students in PE. The studies reviewed provided current research within the

span of years 2005-2011. The studies were located by searching Google Scholar and the

ERIC database. The literature is organized into three categories: (a) research on PE

education motivation, (b) PE gender differences, and (c) the relationship between

physical activity and heath.

Student Motivation During Physical Education

Participation in PE among students can happen due to several reasons. Couturier,

Chepko, and Coughlin (2005) examined four main reasons students participated: (a)

movement, (b) competition, (c) health, and (d) enjoyment. These reasons were examined

in order to see whether or not it made a difference in participation levels. A survey was

administered to over 5,000 middle and high school students from an urban school system.

From this survey, the researchers wanted to understand student perspectives and the

choices being made in their school. Local teachers and administrators paired up with a

nearby college to help discover how students felt about PE. This study aimed to answer

two main questions: (a) What attracts students to PE, and (b) What barriers exist in

students participation?

Couturier et al. (2005) used action research to survey students. The survey

included several open-ended questions about why they liked PE and what they did not

like about PE. Using a ranking system on the survey, the students were asked to rank the

activities currently taught in PE class. Upon completion of the surveys, the researchers

found themes that emerged along with the ranking of approved PE activities. Results

showed that team sports were most well-liked. Following team sports were activities like

swimming, dance, fitness, individual games, and cooperative games. Of the students,

70% of them felt that PE made them healthier, and 69% liked having fun (Couturier et

al., 2005).

According to Couturier et al. (2005), health and having fun were the two main

reasons students chose to participate in PE. The two main reasons for not participating in

PE were as follows: (a) students felt they did not have enough time to change clothes, and

(b) they did not want to go to their following class sweaty. Along with these reasons,

students wanted to have more options to choose from when it came to the activities

played in PE. Courturier et al. established that students can intelligently provide feedback

on how PE courses could have more participation if these issues were corrected.

Choice plays an important role in a students motivation and willingness to

participate in PE class. A study by Hill and Cleven (2006) aimed to determine PE activity

preferences along with gender preferences of students in southern California high

schools. Participants in this study included 22 ninth grade PE classes. Data were gathered

using a survey. The survey asked students to identify the following: (a) their gender, (b)

their activity preference, and (c) if they felt the activities could be taught and played in a

coeducational setting, or if a single-gender class would be more appropriate. In addition

to asking students activity preference, students were also asked whether PE ranked

among their favorite classes. The researchers speculated that differences might exist in

choice of activity due to the fact that many boys chose specific activities that were

competitive, while girls preferences focused more on individual sports. This has been

confirmed by much of the research reviewed.

As the researchers (Hill & Cleven, 2006) were analyzing the data they found, of

the 37 activity choices boys and girls selected, Basketball and Softball/Baseball were in

their top five. The differences were important, however. For example, boys chose

Football, Bowling, and Weight Training. Girls selected Volleyball, Swimming, and

Dance. The survey also revealed that 60% of boys chose PE as their favorite subject; only

40% of girls agreed. An important part of this study evaluated gender differences. The

researchers were unable to find significant differences in students preference for

coeducational classes and same-gender classes. Teachers did not agree with students:

44% reported having difficulty with coeducational classes due to differences in choice of

activity and a lack of motivation and participation. It is also worth noting that other

research has shown that students more often receive positive feedback when participating

in single-gender classes. Research has suggested that teachers should survey their

students and provide gender-specific activities when teaching coeducational classes.

Hohepa, Schofield, and Kolt (2005) conducted a qualitative study to explore the

views of high school students towards physical activity and their ideas on how to promote

physical activity during PE. The researchers addressed what benefits students ascribed to

physical activity, the barriers to participating in PE, and the potential activity promoting

strategies to increase physical activity. In the study, 44 students in a New Zealand area

high school were asked questions in a focus group that included a series of nine sessions.

At each session, students were guided to answer questions about the three research

questions posed by the authors. Each session had probes to allow students to discuss the

benefits of being active, availability of activities, and an ecological approach to how to

increase student participation. These sessions were then transcribed to uncover themes in

the areas of: (a) benefits of PE, (b) barriers to allowed activities, and (c) how to increase

physical activity levels. The results showed that students felt restricted to the access and

use of equipment and that peers and self-perception of ability negatively affected

students. Hohepa et al. stated that students would like to be given choices during class

and encouragement from the teacher, which aligns with the findings of Couturier et al.

(2005).

It has been demonstrated by research that intrinsic motivation and selfdetermination are related to persistence in physical activity (Liukkonen, Barkoukis, Watt,

& Jaakkola, 2010). School PE plays an important role in the development of a physically

active lifestyle. Liukkonen et al. examined the impact of a self-determined motivational

climate on students effort in PE. The researchers wanted to evaluate whether the

motivational climate in PE influenced students intentions to participate. Similarly, the

questions asked were about the relationship between motivational theory and the

cognitive, affective, and behavioral mechanisms that determine if students find PE

enjoyable and want to participate or if it causes anxiety.

The participants in the study conducted by Liukkonen et al. (2010) were 338

sixth-grade students from private schools in two large cities. Using quantitative research,

a questionnaire was administered and used multiple regression path analysis for the data.

The questionnaire covered areas of motivational climate, enjoyment, anxiety, and effort.

The area of motivational climate asked students about their self-attitude and experiences

in PE and how they compared to other pupils in their class. The area of enjoyment was

linked to the effect PE had on students, along with their excitement and perceptions of

competence. The researchers noted that one of the most important psychological factors

affecting participation in physical activity was anxiety about success or failure

(Liukkonen et al., 2010).

Liukkonen et al. (2010) hypothesized that a connection would be evident between

enjoyment of PE activities and participation/success in PE courses. The multiple

regression path analysis created a chart to connect the areas from the questionnaire to

each other. Overall, the motivational climate fostering self-determination was associated

with better participation by students along with high enjoyment, low anxiety, and high

effort.

Using the achievement goal theory framework, Moreno-Murcia, Sicilia, Cervell,

Huscar, and Dumitru (2011) assessed the motivational climate of a task-oriented climate

and an ego-oriented climate in relation to discipline and indiscipline responses in PE

classes in a large city in Spain. These researchers had two purposes in mind while

conducting this research while using this framework: (a) to find self-reporting discipline

in PE between task- and goal-oriented motivations and (b) to identify gender differences

in ego and task orientation in self-discipline or indiscipline. A questionnaire that took

approximately 20 minutes to complete was given to 565 students in their second year of

high school in which the median age was 14.5. The questionnaire involved the following:

(a) perception of success, (b) motivational climate in sport, and (c) disciplined and

undisciplined behavior. After completing the questionnaire, the researchers used

MANOVA and several other statistical methods to analyze their data.

Moreno-Murcia et al. (2011) found a connection between motivational climate,

self-reported discipline, and gender. Significantly, they found that a task-oriented climate

was positively correlated to self-reported discipline in the PE activities. As for gender

differences, boys were more inclined to involve themselves in an ego-involved climate

than the girls. Overall, both genders responded better to a task-oriented motivational

climate in which they reported self-discipline.

Ommundsen and Kvalo (2007) conducted a study in response to their observation

that current research has not yet evaluated the role of social-contextual factors as

possibilities related to motivation and enjoyment of physical education. The researchers

wanted to investigate the role of the motivational climate, teacher support, and perceived

competence on students self-regulated motivation in PE class. Ommundsen and Kvalo

asked whether the achievement goal theory and self-determination theory acted as

mediating factors between students motivation in PE. Using a 5-point Likert-type rating

scale questionnaire and path analyses, 194 10th graders enrolled in a Norwegian high

school were asked to be voluntary participants in this study. The 5-point rating scale had

students rank the following: (a) autonomy support of the teacher, (b) motivational

10

climate, (c) autonomy climate in PE, (d) competences in PE, (e) self-regulation of

motivation, and (f) interest/enjoyment. Using quantitative data, the authors used zeroorder relationship, path analysis, and logistic regression to analyze the data. Results

indicated that perceived mastery climate was positively correlated to perceived

competence, autonomy, and teacher support that led to increased motivation.

Consequently, the results indicated that perceived poor competence in PE was negatively

correlated with competence, autonomy, and lack of teacher support. This combination of

factorscompetence, autonomy, and lack of teacher supportrelated ultimately to the

motivation in students.

In an article published in Adolescent Literacy in Perspective, Kevin Perks (2010)

discussed the importance of crafting effective choices for motivating students. The study

was conducted using teachers in American high schools. Teachers were trained on

important factors to consider when giving students choices. Teachers then constructed

choices for student work, using proven motivational strategies. These strategies included

giving students the following: (a) a sense of control, (b) a sense of purpose for the

activity, and (c) a sense of competence. In addition, to suggesting using proven

motivational strategies, teachers were told to offer a small choice of options; however, if

a student had an idea deemed acceptable, the teacher should be flexible. This article used

a qualitative approach to how teachers felt about the effectiveness of crafting effective

choices for students. Perks found that a majority of teachers who received training and

offered choices based on the motivational strategies had a very high success rate in

improving work quality and completion of work.

11

Gender Differences in Physical Education Participation

One of the many issues facing physical education is gender differences in

preference of activity. Constantinou, Manson, and Silverman (2009) posed the following

question: Are girls affected by their gender in coed physical education class? The

problem seen by the researchers was that females are participating less than males in their

coed PE classes. Consequently, the researchers wanted to see if the girls were affected by

their gender, and they also aimed to discover how girls perceive themselves compared to

boys during class. This was an action research study. Seventh- and eighth-grade girls

from a Midwestern school were participants in this study; 98% of the students were

Caucasian, thereby eliminating ethnicity from the study as an important factor. The study

also included two teachers as participants. Formal and informal interviews were

conducted with the teachers and the female students. In addition to interviews, the

authors took field notes on the girls actions during class.

After transcribing the interviews, Constantinou et al. (2009) developed themes.

These themes included: (a) the teachers primary expectations were the same for both

boys and girls, (b) girls hold gender-role stereotypes, and (c) a competitive atmosphere

and peers behavior influence girls participation in and attitude toward physical

education. Traditional PE curriculum was being taught including basic team sports such

as volleyball, soccer, and basketball. Regardless of gender, both males and females were

expected to participate and improve their skills for all activities taught. Girls also

perceived some activities to be girlish or boyish and were not as willing to compete

with the boys in these activities. Overall, the girls agreed that expectations were the same

12

for both genders. Girls also believed that boys were skillful and aggressive, and boys

brought competition into the games. It is worth noting that the behavior of the boys

sometimes created a physically or emotionally unsafe learning environment for the girls

and for other boys. The girls further felt that the boys were putting them down, which

made the girls less likely to want to be on a team with a boy.

PE can be a struggle for some students. Students self-perceptions and gender

often get in the way of their willingness to participate. What attracts students to PE and

what barriers exist in students participation? Couturier, Chepko, and Coughlin (2007)

performed a two-part action research study to discover how students perceive PE and

what makes them want to participate or not participate during class. The first part of the

study focused on what motivates them; this portion of the study focused on gender

preferences of the same group of students. The question the posed was: Do boys and

girls activity preferences differ? Middle and high school teachers noticed that some

activities had higher participation than others.

In the study conducted by Couturier et al. (2007), a survey was given to over

5,000 students from middle and high school in an urban school system. Examining the

surveys and the themes that arose, the researchers found which activities had high levels

of participation and which activities did not. The researchers compared the activities by

gender to find where the differences were occurring. The results showed no significant

differences found in the area of enjoyment. The largest gaps were found between the

preferred activities. Males chose team and individual sports, due to the competition and

the physicality required by these activities. In contrast, females chose activities that

13

required less competition and allowed them to work at their own pace. Females wanted to

participate in activities such as fitness and dance. Other big differences found between

males and females were environmental issues including the following: (a) not having

enough time to change, (b) not wanting to shower, and (c) preferring not to go to the next

class sweaty. These findings are also similar to the other studies which showed that girls

felt unsafe when participating with the boys.

In the study by Wilkinson and Bretzing (2011), the authors identified a problem

with the physical activity of high school students, particularly girls. They wanted to

discover what girls perceptions of physical education were. Wilkinson and Bretzing

wanted to discover what PE educators could do to provide curricula that would teach

female students to be more physically active throughout life. The researchers of this study

proposed a fitness unit to be taught to female students at a high school in the

Intermountain West. Through this fitness unit, themes developed on how the girls felt

towards the fitness activities compared to traditional PE activities. In all, 88 students

participated in the qualitative research study.

The researchers (Wilkinson & Bretzing, 2011), in cooperation with a PE teacher,

administered an open-ended questionnaire about the fitness unit they completed. During

the unit, field notes were also taken to find insight, emerging ideas, and student

conversations. The questionnaire helped develop the following themes about fitness: (a)

health-promoting, (b) fun and varied, (c) more physically active, (d) easier skills than

sports, (e) good lifetime activities, (f) ease to schedule outside of school, (g) a help in

increasing other abilities, and (h) not competitive. The activities included in the fitness

14

unit were Pilates, kickboxing, and core training. During acquisition of field notes, the

authors noted that many of the girls had gone to a class at the local gym or were feeling

better about the way they were able to move. Many girls also noted that these activities

were easier for them to participate in, and they could follow the teachers lead more

easily. When compared to traditional PE, fitness was preferred 74% to 18% by the female

students.

The Relationship Between Physical Activity and Health

Reducing childrens physical activity during childhood and adolescence increases

their risk for cardiovascular disease in adulthood. So why are students less physically

active than ever? Beets and Pitetti (2005) desired to see if students who demonstrated

high levels of physical activity by participating in both PE and school-sponsored sports

had better cardiovascular fitness, muscle strength, flexibility, and body-mass index (BMI)

than those who participate solely in PE. The participants for this study were 187 high

school students aged 14-19 from a Midwestern city. To compare the two groups of

students, quantitative data were used from a fitness test called FITNESSGRAM.

FITNESSGRAM measured the speed of each students 20-meter shuttle, the number of

90-degree sit-ups completed, the sit and reach, and the measurement of the students

BMI.

Beets and Pitetti (2005) analyzed these data from FITNESSGRAM through SPSS

software. The data revealed that males and females in school-sponsored sports and PE

had a faster 20-meter shuttle and were able to complete more sit-ups. No significant

difference in BMI or the sit and reach appeared, however. The authors reported that these

15

findings suggested that the current PE environment was not providing activities of

sufficient intensity and duration to improve cardiovascular fitness. Although, PE classes

do not provide enough cardiovascular activity, they do promote weight management and

muscle training, which if carried outside of the PE class can create a more active lifestyle.

The objective of a study by Hannon (2008) was to examine the physical activity

levels of overweight and non-overweight African American and Caucasian students

during game play in PE class. Hannon wanted to uncover if previous studies on physical

activity with non-overweight and overweight students were correct. He sought to

discover if a difference appeared between African American and Caucasian students, and

if the difference would differ by gender also. The participants for this study were 198

high school students in a Southwestern U.S. school.

After establishing body fat percentages, Hannon (2008) categorized the students

as either overweight or not overweight. They were further separated by gender and

ethnicity. Using a quantitative research design, a questionnaire was given to each student

along with observations done by Hannon on composition, age, gender, and race for each

student individually. The data computed BMI and body fat percentage, which were then

coded and organized into groups of gender, race, and weight. At the beginning of each PE

session, all students participating in the study were given a pedometer. Each day, an

assistant handed out, collected, and recorded the information from the pedometer. Steps

per activity were converted into steps per minute. At the end of the study, Hannon

analyzed that data using SPSS software. Results showed no significant differences in the

number of steps taken during PE between overweight and non-overweight students. The

16

differences came in the areas of gender and race. Males were more physically active than

females. In addition, the results revealed that Caucasians had more steps per minute than

African Americans, regardless of activity.

Participation in PE and sports is dropping (Johnston et al., 2007). The purpose of

their study was to determine current levels of PE and sports in secondary schools.

Johnston et al. posed three questions: (a) What are the current levels of PE participation,

(b) What are the current requirements, and (c) Do PE participation and requirements

affect racial and socioeconomic levels? This study was conducted as part of a nationwide

school survey titled YES. YES is given to principals across the nation. This survey

collects a variety of information about the school. For the purpose of this study,

administrators answered questions about physical activity at their school, including rates

of sports, participation in PE, and required credits of PE. This survey was given to over

500 principals and was analyzed using a comparative quantitative method. After

completion of the surveys, the researchers were given the demographic information on

the schools including the following: (a) gender, (b) race, (c) socioeconomic status (SES),

(d) urbanicity, and (e) region. They were also given the information on PE at the schools.

Johnston et al. (2007) weighted and distributed the data into student

characteristics and by grade level. The researchers also compared middle and high school

programs, and racial groups along with SES levels. Tables were created to show the totals

in each group along with the means. In each table, calculations indicated comparisons to

other racial or gender groups. The study found that between grades eight and 12,

participation rates drastically declined. Further, less participation was seen in low SES

17

areas. Similar to other studies, this study showed less participation from African

American and Hispanic students than from Caucasian students.

Wiersma and Sherman (2008) took a psychological perspective to evaluate the

use of youth fitness tests in PE classrooms. The article was written using data from

previous studies dating back to the 1950s when President John F. Kennedy implemented

the initial use of fitness tests in public schools. The researchers question was one of

effectiveness of fitness testing as motivation for better performance. How would fitness

tests affect students (a) perceptions of competence, (b) intrinsic and extrinsic motivation,

(c) enjoyment, (d) goal orientation, and (e) physical activity promotion? Researchers

hypothesized that if explicitly taught and developed correctly, fitness testing could be one

aspect of a comprehensive PE curriculum used to motivate students. Researchers used

data published in past research that used the FITNESSGRAM test along with the PACER

fitness test. The outcomes were assessed quantitatively before being applied to the

psychological areas of, goal-orientation, competence, motivation, and cognitive

evaluation theories. In addition to using psychological theories, group size of testing was

also taken into account.

After reviewing the data, Wiersma and Sherman (2008) found that from a

psychological perspective, fitness testing can be an enjoyable and motivating tool for

students. In addition, if fitness testing is going to be used, it should be appropriately

taught and practiced with students before an official test is given. They also found that

when fitness testing is used as competition, students had negative feeling towards the test;

18

however, when used to evaluate student growth followed by goals for the next test,

students reacted positively and with greater motivation.

Underprivileged students are less physically active than those of a higher SES. It

was reported that only 50% of youth in these areas were receiving amount of physical

activity recommended by the surgeon general. Wilson, Evans, Williams, Mixon, Sirard,

and Pate (2005) aimed to give underprivileged students an opportunity to participate in

physical activity outside of the required school day. The participants in this study were 48

students aged 11-14. These students attended a low SES middle school in the rural

southeast. Research was conducted using a quasi-experimental design in which students

answered a questionnaire, participated in an after school fitness intervention program,

and had their levels of physical activity measured. The questionnaire was used to assess

students self-concept of their physical activity.

Results (Wilson et al., 2005) showed that most students had a moderate selfconcept of their physical activity and received enough exercise during the week. Students

participating in the after school program were then asked to provide a list of activities in

which they would enjoy participating. After reviewing the data, researchers offered the

top choices in the after school program. Offering student choices motivated and

encouraged students to participate with vigorous levels of activity. The program had an

86% retention rate; this was due to students enjoyment of the choices being offered. To

measure levels of physical activity, students wore a heart rate monitor. It was shown that

students in the intervention group spent a greater amount of time engaged in vigorous

physical activity than those participating during PE class. Overall, data results indicated

19

that students participating in the after school intervention program had an increase in

physical activity levels; in addition, their self-concept improved.

20

CHAPTER III

METHODOLOGY

This action research study used a mixed-method design. It took place over 6

weeks. Prior to conducting the research, I completed 5 weeks of participation checklists.

The data from these checklists became my baseline data to compare participation levels

before implementation of the intervention and after the research was complete.

On the first day of the 6-week research period, I offered informed consent

documents. Students 18 years-old or older were able to sign for themselves; however,

students under the age of 18 were required to obtain a signature from parents or

guardians. By the third day, I expected to have enough participants to begin to gather

quantitative data regarding students perceptions of PE. To this end, I administered a

survey that used a Likert-type scale to gain insight into the students perceptions of PE.

The four variables addressed in the survey were: (a) gender, (b) level of motivation, (c)

health, and (d) PE activity preferences. I then analyzed the data to see if connections

could be made among the variables to begin to understand why students do or do not

participate in PE.

After collecting the data from the first week, I used the second week to address

qualitative measures. Using a semi-structured interview, students were asked to step aside

into small groups and answer more in-depth questions following a script to find what

other activities might help with participation. I took careful notes and interpreted what

21

they said to find in what activities students have a desire to participate. In addition, I

asked them about their barriers to participation including social factors.

In weeks 3-5, I implemented new activities suggested by students. These activities

included: (a) tennis, the girls top suggestion; (b) kickball, the boys top suggestion; and

(c) bocce. Bocce was introduced as an alternative to the suggestion of bowling, as the

equipment for bowling is not available. I used a participation checklist to see how many

students participated in the offered activities. The participation checklist was the same as

the one used prior to implementation, but the goal was to determine if participation

increased with the addition of the newly introduced activities. This participation checklist

allowed me to learn if what students said they wanted to participate in would really

increase their participation in PE class.

School Context

This study took place in a high school PE class. Currently, 2,200 students are

enrolled at this high school. The grade levels range from 9-12. The majority of these

students are Hispanic with English as a second language. The school offers standard high

school courses along with the option to attend courses from a local college to gain college

credits. The school also offers a variety of clubs and sports for after school

extracurricular activities.

Participants

This study included 30 students from an inner city high school in a large school

district in the southwestern United States. These students ranged from grades 9-12, ages

22

14 to 18. Fifteen boys and 15 girls participated; of these, 74% are Hispanic, 14% are

Caucasian, and 12% are African American.

Classroom Setting

This study was conducted in a variety of settings. Students reported to the PE

locker rooms where they changed into their PE uniforms and located the teachers

designated activity area. These activity areas include the following: (a) the gymnasium,

(b) the soccer field, (c) the football field, (d) the track, and (e) the outdoor courts. At each

designated area, the teacher brought the necessary equipment for the days activities.

Data Collection and Analysis

The materials used in this study were teacher-created. A 5-point Likert-type scale

survey was administered to all study participants at the beginning of the 6-week research

period to assess student attitudes towards PE. This survey consisted of 11 questions that

were answered by students ranging on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly

agree. Students also had the option of non-applicable if they found the question did not

suit one of the five levels. Student responses were calculated to find the average response

for each question.

The study also included student conferences. These conferences were used to

clarify how students felt about their choices in PE and what social factors, if any,

influenced their participation in PE. These conferences were held randomly with a small

group of 4-6 students. During the conferences, notes were taken and later analyzed to find

patterns and themes that shed light on reasons students participate in PE or not.

23

A participation checklist was used daily and by period to track what activities

were offered and how many students participated in each activity. For students not

participating in an offered activity, an alternative activity was given that was also tracked.

This checklist helped to identify the preferred activities.

The study also included field notes. The field notes were taken twice a week

during 2 class periods for the duration of the 6-week study. The field notes included

anything of importance, paying special attention to the following: (a) with whom students

were interacting, (b) how they were participating, (c) the motivation given, and (d)

statements about PE made by the students. The field notes were compared for common

patterns and themes.

Procedural Plan

The procedure for this action research study involved performing the following

steps:

1. Gather baseline participation data in all my PE classes.

2. Obtain permission from the school and the school district to conduct the

research.

3. Obtain permission from the colleges Institutional Review Board to conduct

the research.

4. Distribute to and receive back consent forms from students.

5. Discuss the purpose of the research and privacy with student participants.

6. Administer the student survey to each participant.

7. Analyze data from the survey.

24

8. Write field notes and complete the participation checklist.

9. Conduct semi-formal student conferences. Student conferences were held

during Week 2 after analyzing the student survey. Questions were prepared

based on student responses. These questions allowed for students to discuss

how they felt about certain aspects of PE. Notes were taken for each question

summarizing the students responses, paying close attention to activities in

which students would like to participate.

10. Plan lessons and activities to reflect student attitudes and interests.

11. Implement new activity choice strategy over a 5-week period.

12. Gather field notes and complete the participation checklist during the

implementation period.

13. Analyze data to gain an understanding of whether students were positively

responding to activities.

14. Conduct additional conferences and/or focus groups with participants to

determine if the changes made during PE had a positive effect on students

participation and motivation during class.

25

CHAPTER IV

RESULTS

The goal of this study was to examine why students express a lack of participation

and motivation during PE class. In particular, student-based choices were analyzed to see

if their availability would affect motivation to participate in PE where traditional sports

such as basketball, football, and soccer were the more common offerings. Participants

were randomly selected from 3 class periods in an urban high school in which grade

levels ranged from 9-12. The data collected consisted of survey answers on 11 Likerttype scale items evaluating: (a) motivation, (b) gender differences, and (c) health. After

collection of the survey, small group interviews were conducted to clarify unanswered

questions and obtain in-depth responses. Student participation charts were used daily to

track the number of participants in each activity.

Survey

Participants were given the 11-item questionnaire before the tracking of

participation began. Since this study mainly focused on motivation and participation, six

questions were geared toward these factors. For example, the first question about

motivation, Question #3, asked about students self-perception of their effort in PE,

resulting in an overall score of 4.32 (agree) for all students, suggesting that both boys and

girls perceive that they make an effort in PE. On another question about motivation,

Question #6, students were asked if they received enough motivation from their teacher.

26

An overall score showed 4.26 agree that they do receive enough motivation from their

teacher.

Question #7 was also about motivation and asked about the interaction with peers

in PE classes. This showed the highest favorability at 4.38 (agree). Of the six questions

about motivation, questions #3, #6, and #7 reported the most consistent levels of

agreement between females and males.

Question #5, again concerning motivation, asked students if they felt embarrassed

while participating in physical activities. Most students did not feel embarrassed (1.82, on

average, disagreed with the statement); however, males (2.64) reported more

embarrassment than females (2.00). When asked on Question #4 if students liked current

activities already being offered in PE, most (3.85) agreed; however, the average response

is somewhat neutral. Further examination revealed that girls (3.47) like the current

activities much less than do boys (4.23).

Question #11, the final question about motivation, referred to the perception of

peer influence on the outcome of the students daily participation in an activity. Results

showed an overall score of 3.03, a neutral response; however, males (3.48) averaged

nearly 1 full point higher than females (2.56) by agreeing with the statement that peer

perception affects their participation. The motivation questions yielded the greatest and

the least agreement for reasons for participating in PE; thus, motivation played a

significant role in participation in PE.

The remaining five questions on the questionnaire involved one gender-difference

question and four health-related questions. The gender-difference question, Question #1,

27

referred to students preference for coeducational PE classes. The results indicated an

overall (3.12) neutral response; however, girls (3.34) would be more likely than boys

(2.86) to participate in PE if the classes were not coed.

The four health questions pertained to students overall daily physical activity and

sleep. Questions #9 and #10 asked about their perception of their overall physical health,

and students, both boys and girls, seemed to agree that their general health was okay.

Males agreed more strongly (4.23) believed that their lack of sleep negatively impacted

their PE participation and performance in school.

In terms of physical activity, the responses to Question #2 revealed that both boys

(3.50) and girls (3.18) generally believe they get enough physical activity outside school.

The tendency of both genders was to indicate on Question #8 that they did not care to

participate in aerobics activities in PE class. The results of the survey are shown in Table

1.

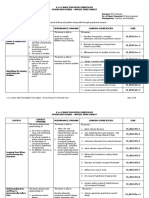

Table 1

Student Survey Results by Variable and Gender

Question #

Variable

Female

Male

3

4

5

6

11

7

1

9

2

8

10

Motivation

Motivation

Motivation

Motivation

Motivation

Motivation

Gender difference

Health

Health

Health

Health

4.18

3.47

2.0

4.35

2.56

4.18

3.34

3.41

3.18

2.52

3.88

4.47

4.23

2.64

4.18

3.48

4.59

2.86

4.23

3.5

2.78

3.94

4.32

3.85

1.82

4.26

3.03

4.38

3.12

3.82

3.21

2.65

3.91

28

Small Group Interviews

After the questionnaire was administered, small group interviews were conducted.

These interview questions were designed to gain insight into what activities the students

wanted offered, their enjoyment, their reasons for not participating, the benefits of PE,

what they would like to see eliminated, and overall safety during class.

Participation and Enjoyment

From these questions, I learned that girls would be more willing to participate if it

were not for having boys in the classroom. Their reasons included safety and

embarrassment. According to the questions on safety, two girls reported feeling unsafe

around the boys, and one boy reported feeling unsafe due to bullying.

When asked about motivation to participate in the currently offered activities, the

students said that they were satisfied with what is currently offered for physical activities.

Along with this response, two frequent reasons were also given. One was that they

wanted to play something that is not feasible in the high school PE setting. The second

was that they liked the opportunity to get out of the regular classroom setting to socialize

with their peers while walking, a physical activity they seemed to enjoy. When discussing

activities to offer, students frequently suggested kickball, tennis, volleyball, and Zumba/

dance. Some of the less feasible suggestions were riding bikes, archery, and swimming.

As reported both on the survey and in the interviews, many students honestly feel

that they get the necessary exercise needed on a daily basis; therefore, receiving

additional exercise in PE is not necessary. For example, they commented that they played

sports outside of school or rode their skateboard or bicycle. Some boys reported they

29

would be more likely to participate if no girls were present with whom to socialize during

PE class because of the distraction involved. Other factors affecting their motivation to

participate included the weather, uniforms, freshmen, and boysfrom the female

respondents.

The factors listed affected the students motivation to participate and explained

the main reasons students did not enjoy PE. When asked exclusively about PE

enjoyment, students stated that they get the chance to be active and fit [outside of

school], go outside, and socialize with friends. This enjoyment transfers to students

feeling that PE benefits them in a number of ways, including staying fit, being healthy,

burning calories, and having energy.

Student Choice of Activities

The interviews were conducted to obtain student choices for participation. From

these interviews, alternative activities chosen by students were: (a) bocce, (b) kickball,

and (c) tennis. These activities were then implemented in the PE classes to see if

motivation would rise if students received their activity choice. Table 2 summarizes the

activity choices before and after data were gathered regarding activity preferences.

Prior to conducting student surveys and interviews regarding activity choice, 5

weeks of data were collected on student participation of already offered choices. Each

week, two activities were offered along with walking as an alternative. Data were

collected from three PE classes, with an average of 282 students per week. Walking was

always offered, and two other choices were offered from the following team sports: (a)

30

football, (b) basketball, (c) soccer, or (d) badminton. On average, participation was

equally divided among Activity 1, Activity 2, and walking.

After data regarding PE activity choice were gathered, Activity 1 was a studentselected activity selected from (a) bocce, (b) kickball, and (c) tennis, Activity 2 was the

traditional teacher-selected activityamong these 5 weeks were soccer, basketball, and

football, and walking was always the third choice. Results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Participation in Activities Before and After Implementation of Student Choice

Baseline participation

Participation with choice

Week

#

Activity 1

Activity 2

Walking

Activity 1

(choice)

Activity 2

Walking

1

2

3

4

5

29.8

31.4

34.0

35.2

33.0

34.0

32.7

30.5

34.5

30.5

36.2

35.9

35.5

30.3

36.5

17.0

31.4

30.2

37.7

33.3

36.2

34.3

34.9

27.1

30.9

46.8

34.3

34.9

35.2

35.8

32.7

32.5

34.9

29.9

32.7

37.4

The first student-identified choice was offered in Week 1; in lieu of bowling,

bocce was offered as bowling equipment was not installed in the school. A significant

decline in participation occurred, with only 17.0% of students participating. Walking

picked up the difference, with 46.8% of students selecting walking in the first week. The

first offering of tennis as a student choice during Week 4 garnered support (37.7%), but

that percentage diminished when tennis was again offered in Week 5 (33.3%).

31

Consistently, both before and after the research was conducted, walking was selected

most often by my PE students.

32

CHAPTER V

DISCUSSION, CONCLUSION, AND IMPLICATIONS

Discussion and Conclusion

As indicated by the data, student-based choices for activity appeared to make only

a limited increase in the motivation to participate. As shown from the survey, the largest

impact was the motivation the teacher brought to the PE setting. This factor linked to the

small group interviews where students stated they enjoyed the teacher-chosen activities

already in place. Unfortunately, I wanted to see change, and this did not happen by giving

students their choice of activity for better motivation to participate in a physical sport. In

Table 2, for example, the data revealed that pre- and post-participation in PE activities

remained the highest in my alternative activity of walking. After gathering information

from the small group interviews, I have come to the conclusion that walking is chosen for

socializing and lack of being embarrassed, and it still gives students the opportunity to

receive some form of physical movement and participation credit for PE class.

I chose to offer walking as an alternative to team sports because I wanted to create

an environment in which physical activity is enforced. As in the research by Liukkonen et

al. (2010), I found that a motivational climate was better for participation because

students had high enjoyment and effort. I found similar results in that my students

seemed to feel that I create a highly motivational climate in which participation in any

activity allows them to achieve a satisfactory grade. The participation may not be in the

33

activities I wish for my students; however, as long as they receive a motivational climate

in which some activity was received, students still appeared to enjoy PE class.

Along with teacher support and creating a positive climate, Ommundsen and

Kvalo (2007) found the same results as Liukkonen et al. (2010). Motivational climate is

highly related to teacher support.

Perks (2010) found that allowing students to make choices was important because

it gave them a sense of control and purpose; this compares favorably to my results. When

I offered the student-suggested activity, the overall mean of participation was lower than

my choice or the alternative, walking. When the student-suggested activity was offered,

walking participation increased significantly; however, when I chose the offered

activities, participation levels stayed consistent in both before and after the inquiry about

motivation, gender preferences, health, and choice of activities. Along with the

motivational factor of student-chosen activities, gender was seen as a major obstacle in

my small group interviews.

The research by Hill and Cleven (2006) found that choosing activities between the

male and female perceptions had cultural norms come into play. In discussion with my

students, I found that females wanted to participate in dance and fitness, and they also

expressed that they did not want a coed setting. On the other hand, males wanted to take

part in more competitive physical sports including basketball and football. This supported

the cultural assumption that males want a more competitive sport environment, while

females want a cooperative environment (Couturier et al., 2005; Hill & Cleven, 2006).

Hohepa et al. (2005) also reported similar results when it came to gender differences and

34

safety. From my group interviews, females expressed that males behavior made them

feel unsafe in the PE environment, making my data results congruent with Hohepa et al.

Gender differences throughout the research in PE has shown that gender plays a major

role in the motivation to participate in PE activities.

Implications

From my study, several implications for teaching PE courses have been shown.

Creating a highly teacher-motivated environment still aligns with past research in that

teacher support is linked to a positive student perception. Future researchers should look

into the differences in offering student-based activities and teacher-chosen activities in a

longitudinal period. In the current research, differences were evident in what students say

they want and what the data showed. For example, my students wanted to choose their

own activities; however, when they were able to choose their activity, they had the lowest

participation rate. According to Wilson et al. (2005), self-discipline was not correlated

with motivation to participate. This resonates with my data in that being disciplined and

having the teacher choose the activity resulted in better participation, discipline, and

motivation.

Not only has research shown that cultural norms come into play, but apparent

sport favorability has also appeared among students in a low SES. In my results, the

highest levels of participation in an offered sport activity were basketball and football.

Johnston et al. (2007) found lower participation rates in low SES areas. My data indicated

that my students, although in a low SES area, do participate in activities; however, they

would rather walk. My students frequently stated that they believed that they have

35

received enough activity outside of the school setting. Future researchers should look into

the differences between high SES and low SES motivation to participate in PE and what

sport-related activities they feel is enjoyable. This would be useful for all teachers so they

could alter their PE program to incorporate and fit the student needs of their area.

Reflection

All in all, my research has been highly insightful in that I feel confident in leading

my chosen activities because of the level of motivation and participation my students

feel. It was interesting to learn that the student-based choices did not align with past

research that found that students preformed better with their own chosen activities.

Creating a highly motivational climate in which all students feel equal and safe continues

to show positivity in PE participation. I will continue to enforce a motivational

environment in which activities like basketball, football, and walking will be a major part

of my PE program. These activities showed the greatest participation and enjoyment,

which is what I hope to sustain.

36

References

Beets, M. W., & Pitetti, K. H. (2005). Contribution of physical education and sport to

health-related fitness in high school students. Journal of School Health, 75(1), 2530.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Childhood overweight and obesity.

Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/index.html

Constantinou, P., Manson, M., & Silverman, S. (2009). Female students perception

about gender-role stereotypes and their influence on attitude toward physical

education. Physical Educator, 66(2), 85-96.

Couturier, L. E., Chepko, S., & Coughlin, M. A. (2005). Student voicesWhat middle

and high school students have to say about physical education. Physical Educator,

62(4), 170-177.

Couturier, L. E., Chepko, S., & Coughlin, M. A. (2007). Whose gym is it? Gendered

perspectives on middle and secondary school physical education. Physical

Educator, 64(3), 152-158.

Hannon, J. C. (2008). Physical activity levels of overweight and nonoverweight high

school students during physical education classes. Journal of School Health,

78(8), 425-431. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00325.x

37

Hill, G., & Cleven, B. (2006). A comparison of 9th grade male and female physical

education activities preferences and support for coeducational groupings. Physical

Educator, 62(4), 187-197.

Hohepa, M., Schofield, G., & Kolt, G. S. (2005). Physical activity: What do high school

students think? Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 328-336. doi:10.1016/j.

jadohealth.2005.12.024

Johnston, L. D., Delva, J., & OMalley, P. M. (2007). Sports participation and physical

education in American secondary schools. American Journal of Preventive

Medicine, 33(4), 195-208. doi:10.1012/j.amepre.2007.07.015

Liukkonen, J., Barkoukis, V., Watt, A., & Jaakkola, T. (2010). Motivational climate and

students emotional experiences and effort in physical education. Journal of

Educational Research, 103(5), 295-308. doi:10.1080/00220670903383044

Moreno-Murcia, J., Sicilia, A., Cervello, E., Huescar, E., & Dumitru, D. C. (2011). The

relationship between goal orientations, motivational climate and self-reported

discipline in physical education. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 10, 119129.

Ommundsen, Y., & Kvalo, S. E. (2007). Autonomy-mastery, supportive or performance

focused? Different teacher behaviors and pupils outcomes in physical education.

Scandinavian Journal of Education Research, 51(4), 385-413. doi:10.1080/00313

830701485551

Perks, K. (2010). Crafting effective choices to motivate students. Adolescent Literacy in

Perspective, 2, 2-15.

38

Physical Activity Council. (2012). The Physical Activity Councils annual study tracking

sports, fitness and recreation participation in the USA. Retrieved from www.

physicalactivitycouncil.com/PDFs/2012PacReport.pdf

Wiersma, L. D., & Sherman, C. P. (2008). The responsible use of youth fitness testing to

enhance student motivation, enjoyment, and performance. Measurement in

Physical Education and Exercise Science, 12, 167-183. doi:10.1080/109136708

02216148

Wilkinson, C., & Bretzing, R. (2012). High school girls perceptions of selected fitness

activities. Physical Educator, 68(2), 58-65.

Wilson, D. K., Evans, A. E., Williams, J., Mixon, G., Sirard, J., & Pate, R. (2005). A

preliminary test of student-centered intervention on increasing physical activity in

underserved adolescents. The Society of Behavioral Medicine, 30(5), 119-124.

39

Appendix A

Letter of Informed Consent

40

Date: January 22, 2013

Dear Student,

The following information is provided to help you decide whether you wish to

participate in a research study. You should be aware that you are free to decide not to

participate or may withdraw at any time without affecting our teacher-student

relationship.

The purpose of this study is to discover what will motivate students to have

greater participation during physical education class.

Data group interviews will be conducted at random. Field notes about student

behaviors will also be taken, and a participation checklist will be used to keep track of

what activities students are participating in. At the end of the study, the information will

be analyzed to find what areas students have the highest rate of participation in.

Do not hesitate to ask questions about the study before it begins or while the

research is being conducted. I would be happy to share the findings with you after the

research is completed. Your name will not be associated with the research findings in any

way, and only the researcher will know your identity.

There are no known risks and/or discomfort associated with this study. The

expected benefits are associated with your participation information about the

experiences in learning research methods. The benefits of this study will help increase

students participation and motivation in PE.

Your participation is voluntary. By signing this consent form and returning it to

the PE office you are agreeing to participate.

_____________________________________

Signature

Billy H. Barker

M.A.T. Student

Sierra Nevada College

_______________________

Date

41

Date: January 22, 2013

Dear Parent or Guardian,

Your child is invited to participate in a research study, Gaining Participation in

PE, conducted by Billy Barker under the supervision of Dr. Marsha Kobre Anderson for

the Spring semester 2013 at Sierra Nevada College. This study is part of a masters

thesis. If you agree to your childs participation, he or she will be one of approximately

30 subjects. I anticipate that your childs participation in this study will take normal class

time for approximately 6 weeks.

The purpose of this study is to help me better understand what I can do to help my

students participate in PE. Students will be offering suggestions and participating in new

activities suggested by other students.

There are no physical or psychological risks for your child by participating in this

study.

Your child will benefit from this study by participating in activities selected by

their peers that may be interesting to them.

Any information that is obtained in connection with this study and that can be

identified with your child will remain confidential and will be disclosed only with your

permission or as required by law. Confidentiality will be maintained by means of a

numbering process. Data collected will be coded with numbers. No names will appear on

any information.

Your childs participation in this study is voluntary; you may withdraw him or her

at any time without consequences of any kind. Your child may also choose not to answer

any questions that he or she doesnt want answered specific to the study and still remain

in the study. I may withdraw your child from this research if circumstances arise which

warrant doing so.

If you have any questions about the research, please feel free to contact me at

bhbarker@interact.ccsd.net or my thesis chair, Dr. Marsha Kobre Anderson at

manderson@sierranevada.edu.

You may withdraw your consent at any time and discontinue your childs

participation without penalty. You are not waiving any legal claims, rights, or remedies

because of your participation in this research study. If you have questions regarding your

42

rights as a research participant, contact Dr. Maria J. Meyerson, Sierra Nevada College,

4300 E. Sunset Road, Suite E1, Henderson, Nevada 89014 (702-434-6599).

Sincerely yours,

Billy Barker

Signature of Research Participant or Legal Representative:

I have read this form and received a copy of it. I have had all of my questions answered

to my satisfaction. I agree to take part in this study or I agree to allow my child to take

part in this study.

Name of Participant or Child

Signature of Parent(s) or legal representative(s)

Date

Signature of Witness

Date

43

Appendix B

Survey and Interview Questions

44

Physical

Education

Survey

Grade Level 9

Gender

10

11

Female

12

Male

Strongly

Agree

I would be more likely to

participate in PE if the class was

not coed.

I get enough physical activity

outside of school.

I generally put forth effort in PE

class.

I like the activities being offered

during PE.

I feel embarrassed during sporting

activities.

I get enough motivation from my

teacher to participate.

Peers affect how I perform during

PE class.

I would like to participate in

aerobic activities during PE.

My lack of sleep and what I do

outside of school affect my

participation in PE.

I feel PE improved my overall

health.

I like getting out of the classroom

and interacting with my peers in a

PE setting.

Agree

Neutral

Disagree

Strongly

Disagree

45

Interview Questions

1. Do you enjoy PE? Why or why not?

2. When you choose not to participate in class what are your reasons?

3. If you could have your choice of any activities to participate in during class, what

would they be?

4. What would you like to see eliminated from PE?

5. What do you think are the benefits of PE?

6. Do you feel safe during PE? If not, what makes you feel unsafe?

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Argumentative EssayDokument6 SeitenArgumentative Essayapi-331322127Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reflection EssayDokument8 SeitenReflection Essayapi-252920642100% (1)

- Students' Attitudes Towards Physical Education Ludabella Aurora C. SanesDokument7 SeitenStudents' Attitudes Towards Physical Education Ludabella Aurora C. SanesJR100% (1)

- CSWIP-WS-1-90, 3rd Edition September 2011 PDFDokument10 SeitenCSWIP-WS-1-90, 3rd Edition September 2011 PDFdanghpNoch keine Bewertungen

- FARNACIO-REYES RA8972 AQualitativeandPolicyEvaluationStudyDokument16 SeitenFARNACIO-REYES RA8972 AQualitativeandPolicyEvaluationStudyJanelle BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attitudes of Students with Learning Disabilities Toward Participation in Physical Education: a Teachers’ Perspective - Qualitative ExaminationVon EverandAttitudes of Students with Learning Disabilities Toward Participation in Physical Education: a Teachers’ Perspective - Qualitative ExaminationNoch keine Bewertungen

- English 1201 - Rough DraftDokument8 SeitenEnglish 1201 - Rough Draftapi-483711291Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gender Isu in Physical EducationDokument8 SeitenGender Isu in Physical EducationJane HoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pe 1 1Dokument6 SeitenPe 1 1api-330991089Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gender Issues in Physical EducationDokument44 SeitenGender Issues in Physical EducationMilanie Miscala Panique100% (7)

- Signature Assignment FinalDokument16 SeitenSignature Assignment Finalapi-263735711Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Effects of Students ParticipationDokument19 SeitenThe Effects of Students ParticipationMary Marmeld UdaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- PR Chapter 1 G2 12 01 22 10pmDokument20 SeitenPR Chapter 1 G2 12 01 22 10pmJanyl ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Signature Assignment Rough DraftDokument11 SeitenSignature Assignment Rough Draftapi-263735711Noch keine Bewertungen

- Capstone - ReportDokument54 SeitenCapstone - Reportapi-341959014Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jose Conrad Braña - Reflection PaperDokument11 SeitenJose Conrad Braña - Reflection PaperJose Conrad C. BrañaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fountain, DougDokument25 SeitenFountain, Dougarup giriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compiled February 27 MANUSCRIPTDokument25 SeitenCompiled February 27 MANUSCRIPTStarlly Matriano ValienteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan: Physical EducationDokument3 SeitenLesson Plan: Physical Educationapi-396973326Noch keine Bewertungen

- Scholl Assessmentppe310Dokument6 SeitenScholl Assessmentppe310api-270320670Noch keine Bewertungen

- English Essay 2Dokument3 SeitenEnglish Essay 2Aleksandra PetrovićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis WorkDokument25 SeitenThesis Workapi-314559956Noch keine Bewertungen

- Freeman Desiree Assignment13-1Dokument16 SeitenFreeman Desiree Assignment13-1api-238107352Noch keine Bewertungen

- Senior Capstone PaperDokument23 SeitenSenior Capstone Paperapi-270413105Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rios Vanessa Assignment3-1 Ppe310Dokument7 SeitenRios Vanessa Assignment3-1 Ppe310api-246312242Noch keine Bewertungen

- BalancingDokument38 SeitenBalancingNorman AntonioNoch keine Bewertungen

- OBESEDokument23 SeitenOBESEJeraldine Gomez AningatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comprehensive School AssessmentDokument11 SeitenComprehensive School Assessmentapi-271276388Noch keine Bewertungen

- Physically Active Students Learn BetterDokument5 SeitenPhysically Active Students Learn Betterapi-507778293Noch keine Bewertungen

- Final Research PaperDokument13 SeitenFinal Research PaperJarett WallsNoch keine Bewertungen

- SampuDokument3 SeitenSampuslypiekunNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Does Being Involved in High School Extra Curriculars Affect The Students Overall High School Experience?Dokument8 SeitenHow Does Being Involved in High School Extra Curriculars Affect The Students Overall High School Experience?api-485814878Noch keine Bewertungen

- Comprehensive School AssessmentDokument9 SeitenComprehensive School Assessmentapi-250800207Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment mvsc486Dokument19 SeitenAssessment mvsc486api-650024037Noch keine Bewertungen

- BREAKING GENDER STEREOTYPES in pHYSICAL EDUCATION cLASS 2Dokument103 SeitenBREAKING GENDER STEREOTYPES in pHYSICAL EDUCATION cLASS 2Mikah de LeonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dissertation For Physical EducationDokument8 SeitenDissertation For Physical EducationPaySomeoneToWritePaperCanada100% (1)

- Final Ppe Sig AssignDokument17 SeitenFinal Ppe Sig Assignapi-250800207Noch keine Bewertungen

- UpsandDownsofLifeFactorsaffectingthemotivationofFirstYearCollegeStudentsoftheUST-AlfredoM VelayoColleg EditedDokument12 SeitenUpsandDownsofLifeFactorsaffectingthemotivationofFirstYearCollegeStudentsoftheUST-AlfredoM VelayoColleg EditedJenifer PableoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sarah Gormley Eip Edited - 3Dokument6 SeitenSarah Gormley Eip Edited - 3api-405492729Noch keine Bewertungen