Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Gulf Resorts vs. Phil Charter Insurance

Hochgeladen von

Tonton Reyes0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

44 Ansichten5 Seitenwer

Originaltitel

Gulf Resorts Inc vs Phil Charter

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenwer

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

44 Ansichten5 SeitenGulf Resorts vs. Phil Charter Insurance

Hochgeladen von

Tonton Reyeswer

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 5

Gulf Resorts Inc. vs. Philippine Charter InsuranceCorporation [G.R.

No. 156167 May 16, 2005]

Facts: Gulf Resorts is the owner of the Plaza Resortsituated at

Agoo, La Union and had its properties in saidresort insured

originally with the American HomeAssurance Company (AHAC). In

the first 4 policiesissued, the risks of loss from earthquake shock

was

extended only to petitioners two swimming pools. Gulf

Resorts agreed to insure with Phil Charter theproperties covered

by the AHAC policy provided thatthe policy wording and rates in

said policy be copied inthe policy to be issued by Phil Charter. Phil

Charterissued Policy No. 31944 to Gulf Resorts covering theperiod

of March 14, 1990 to March 14, 1991 forP10,700,600.00 for a total

premium of P45,159.92. thebreak-down of premiums shows that

Gulf Resorts paidonly P393.00 as premium against earthquake

shock(ES). In Policy No. 31944 issued by defendant, the shock

endorsement provided that In consideration of the

payment by the insured to the company of the sumincluded

additional premium the Company agrees,notwithstanding what is

stated in the printed conditionsof this policy due to the contrary,

that this insurancecovers loss or damage to shock to any of the

propertyinsured by this Policy occasioned by or through or

inconsequence of earthquake (Exhs. "1-D", "2-D", "3-A","4-B", "5A", "6-D" and "7-C"). In Exhibit "7-C" the word"included" above

the underlined portion was deleted.On July 16, 1990 an

earthquake struck Central Luzon

and Northern Luzon and plaintiffs properties covered

by Policy No. 31944 issued by defendant, including thetwo

swimming pools in its Agoo Playa Resort weredamaged.Petitioner

advised respondent that it would be making aclaim under its

Insurance Policy 31944 for damages on

its properties. Respondent denied petitioners claim on

the ground that its insurance policy only affordedearthquake

shock coverage to the two swimming poolsof the resort. The trial

court ruled in favor of respondent. In its ruling, the schedule

clearly showsthat petitioner paid only a premium of P393.00

againstthe peril of earthquake shock, the same premium it

hadpaid against earthquake shock only on the twoswimming

pools in all the policies issued by AHAC.Issue: Whether or not the

policy covers only the twoswimming pools owned by Gulf Resorts

and does notextend to all properties damaged thereinHeld: YES.

All the provisions and riders taken andinterpreted together,

indubitably show the intention of the parties to extend earthquake

shock coverage to thetwo swimming pools only. An insurance

premium is theconsideration paid an insurer for undertaking

toindemnify the insured against a specified peril. In fire,casualty

and marine insurance, the premium becomes adebt as soon as

the risk attaches. In the subject policy,no premium payments

were made with regard toearthquake shock coverage except on

the twoswimming pools. There is no mention of any

premiumpayable for the other resort properties with regard

toearthquake shock. This is consistent with the history of

petitioners insurance policies with AHAC.

Petitioner contends that pursuant to this rider, no qualifications

were placed on the scope of the earthquake shock coverage.

Thus, the policy extended earthquake shock coverage to all of the

insured properties.

It is basic that all the provisions of the insurance policy should be

examined and interpreted in consonance with each other.[25] All

its parts are reflective of the true intent of the parties. The policy

cannot be construed piecemeal. Certain stipulations cannot be

segregated and then made to control; neither do particular words

or phrases necessarily determine its character. Petitioner cannot

focus on the earthquake shock endorsement to the exclusion of

the other provisions. All the provisions and riders, taken and

interpreted together, indubitably show the intention of the parties

to extend earthquake shock coverage to the two swimming pools

only.

A careful examination of the premium recapitulation will show

that it is the clear intent of the parties to extend earthquake

shock coverage only to the two swimming pools. Section 2(1) of

the Insurance Code defines a contract of insurance as an

agreement whereby one undertakes for a consideration to

indemnify another against loss, damage or liability arising from an

unknown or contingent event. Thus, an insurance contract exists

where the following elements concur:

The insured has an insurable interest;

The insured is subject to a risk of loss by the happening of the

designated peril;

The insurer assumes the risk;

Such assumption of risk is part of a general scheme to distribute

actual losses among a large group of persons bearing a similar

risk; and

In consideration of the insurer's promise, the insured pays a

premium.[26] (Emphasis ours)

An insurance premium is the consideration paid an insurer for

undertaking to indemnify the insured against a specified peril.[27]

In fire, casualty, and marine insurance, the premium payable

becomes a debt as soon as the risk attaches.[28] In the subject

policy, no premium payments were made with regard to

earthquake shock coverage, except on the two swimming pools.

There is no mention of any premium payable for the other resort

properties with regard to earthquake shock. This is consistent with

the history of petitioners previous insurance policies from AHACAIU.

In sum, there is no ambiguity in the terms of the contract and its

riders. Petitioner cannot rely on the general rule that insurance

contracts are contracts of adhesion which should be liberally

construed in favor of the insured and strictly against the insurer

company which usually prepares it.[31] A contract of adhesion is

one wherein a party, usually a corporation, prepares the

stipulations in the contract, while the other party merely affixes

his signature or his "adhesion" thereto. Through the years, the

courts have held that in these type of contracts, the parties do

not bargain on equal footing, the weaker party's participation

being reduced to the alternative to take it or leave it. Thus, these

contracts are viewed as traps for the weaker party whom the

courts of justice must protect.[32] Consequently, any ambiguity

therein is resolved against the insurer, or construed liberally in

favor of the insured.[33]

The case law will show that this Court will only rule out blind

adherence to terms where facts and circumstances will show that

they are basically one-sided.[34] Thus, we have called on lower

courts to remain careful in scrutinizing the factual circumstances

behind each case to determine the efficacy of the claims of

contending parties. In Development Bank of the Philippines v.

National Merchandising Corporation, et al.,[35] the parties, who

were acute businessmen of experience, were presumed to have

assented to the assailed documents with full knowledge.

We cannot apply the general rule on contracts of adhesion to the

case at bar. Petitioner cannot claim it did not know the provisions

of the policy. From the inception of the policy, petitioner had

required the respondent to copy verbatim the provisions and

terms of its latest insurance policy from AHAC-AIU. The testimony

of Mr. Leopoldo Mantohac, a direct participant in securing the

insurance policy of petitioner, is reflective of petitioners

knowledge

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Promissory NoteDokument1 SeitePromissory NoteTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Affidavit of Consent Exhumation 2 (BONG)Dokument3 SeitenAffidavit of Consent Exhumation 2 (BONG)Tonton Reyes100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Jenelyn AtilanoDokument1 SeiteJenelyn AtilanoTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- A.T. Reyes Law Office: Mr. Eldred Manuel President Simply Fast Wealth and Health SolutionDokument1 SeiteA.T. Reyes Law Office: Mr. Eldred Manuel President Simply Fast Wealth and Health SolutionTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Compromise Agreement (NestorManibog)Dokument3 SeitenCompromise Agreement (NestorManibog)Tonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Engr. Gerardo P. CorsigaDokument2 SeitenEngr. Gerardo P. CorsigaTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deed of Acknowledgment of Debt: Know All Men by These PresentsDokument2 SeitenDeed of Acknowledgment of Debt: Know All Men by These PresentsTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Complaint Against Tito Cuerdo (Collection of Sum of Money)Dokument8 SeitenComplaint Against Tito Cuerdo (Collection of Sum of Money)Tonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Map (Office)Dokument1 SeiteMap (Office)Tonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Demand Letter (Cha Sanidad)Dokument3 SeitenDemand Letter (Cha Sanidad)Tonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- Promissory Note Joint MakerDokument1 SeitePromissory Note Joint MakerTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Documentary Exhibits For The Defense (PP vs. ATR)Dokument4 SeitenList of Documentary Exhibits For The Defense (PP vs. ATR)Tonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Contract of Employment SummaryDokument6 SeitenContract of Employment SummaryTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Ontract For Probationary EmploymentDokument8 SeitenOntract For Probationary EmploymentTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Contract of Lease (Daymon)Dokument3 SeitenContract of Lease (Daymon)Tonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Milf Resort Build 4.1 WalkthroughDokument10 SeitenMilf Resort Build 4.1 WalkthroughNitin Saini0% (2)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Cirila MontesDokument1 SeiteCirila MontesTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Template Comments Opposition To Motion For ReconsiderationDokument2 SeitenTemplate Comments Opposition To Motion For ReconsiderationTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demand Letter (Donalyn)Dokument1 SeiteDemand Letter (Donalyn)Tonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rejoinder: National Labor Relations CommissionDokument7 SeitenRejoinder: National Labor Relations CommissionTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demand Letter (Cha Sanidad)Dokument3 SeitenDemand Letter (Cha Sanidad)Tonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Questions (JUDAF) RobertDokument1 SeiteQuestions (JUDAF) RobertTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supplemental-Affidavit (Norman Benjamin)Dokument4 SeitenSupplemental-Affidavit (Norman Benjamin)Tonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Template Comments Opposition To Motion For ReconsiderationDokument2 SeitenTemplate Comments Opposition To Motion For ReconsiderationTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ex Parte Motion To Set The Case For Trial (Narson)Dokument3 SeitenEx Parte Motion To Set The Case For Trial (Narson)Tonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complaint-Affidavit Intriguing Against HonorDokument2 SeitenComplaint-Affidavit Intriguing Against HonorConsigliere Tadili75% (4)

- Rejoinder-Affidavit (Sharlene Callado)Dokument11 SeitenRejoinder-Affidavit (Sharlene Callado)Tonton Reyes100% (3)

- Complaint-Affidavit Intriguing Against HonorDokument2 SeitenComplaint-Affidavit Intriguing Against HonorConsigliere Tadili75% (4)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Junsan Case Comments Opposition To Motion For ReconsiderationDokument3 SeitenJunsan Case Comments Opposition To Motion For ReconsiderationPaul Espinosa50% (4)

- Readme Compressed VersionDokument1 SeiteReadme Compressed VersionTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 16 Aladdin Hotel Co V BloomDokument7 Seiten16 Aladdin Hotel Co V BloomlabellejolieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bucton vs. GabarDokument1 SeiteBucton vs. GabarJesa DumocloyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gujarat State Eligibility Test: Gset SyllabusDokument6 SeitenGujarat State Eligibility Test: Gset SyllabussomiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vida Divina v. T1 ProcessingDokument9 SeitenVida Divina v. T1 ProcessingThompson BurtonNoch keine Bewertungen

- CIVIL LAW REVIEW II: SALES, LEASES, AGENCY, PARTNERSHIP, TRUST AND CREDIT TRANSACTIONSDokument75 SeitenCIVIL LAW REVIEW II: SALES, LEASES, AGENCY, PARTNERSHIP, TRUST AND CREDIT TRANSACTIONSChristopher Sj SandovalNoch keine Bewertungen

- CIVREV-Property DigestsDokument160 SeitenCIVREV-Property DigestsMiguel CasimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sta. Fe Realty vs. SisonDokument9 SeitenSta. Fe Realty vs. SisonKristine KristineeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- SC upholds liquidation of unlawful partnership fundsDokument6 SeitenSC upholds liquidation of unlawful partnership fundsJesa BayonetaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03 Evidence - Rule 130 Statute of FraudsDokument16 Seiten03 Evidence - Rule 130 Statute of FraudsMa Gloria Trinidad ArafolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engineering Economics: 3170615-Eee&C (Assignment)Dokument4 SeitenEngineering Economics: 3170615-Eee&C (Assignment)yashrajsinh baradNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Case Brief on Enforcing Kharch-i-Pandan AgreementDokument5 SeitenCase Brief on Enforcing Kharch-i-Pandan AgreementRaghavendra NadgaudaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHUA V CSC G.R. No. 88979Dokument5 SeitenCHUA V CSC G.R. No. 88979Ariza ValenciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Aspect - Module 1 - Ruidera Marianne BSHM III-CDokument8 SeitenLegal Aspect - Module 1 - Ruidera Marianne BSHM III-CMarianne RuideraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedies - Full Course NotesDokument40 SeitenRemedies - Full Course NotesKaran Singh100% (1)

- Internacional Privado Def PDFDokument164 SeitenInternacional Privado Def PDFKavyaBalajiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recto Law and Maceda LawDokument15 SeitenRecto Law and Maceda LawZicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heirs of Sofia Quirong Vs Development Bank of The Philippines - G.R. No 173441Dokument6 SeitenHeirs of Sofia Quirong Vs Development Bank of The Philippines - G.R. No 173441Ivy VillalobosNoch keine Bewertungen

- TM502 User GuideDokument70 SeitenTM502 User GuideMiles LewittNoch keine Bewertungen

- D 1 XMDokument496 SeitenD 1 XMVikasSharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trainee AgreementDokument3 SeitenTrainee Agreementanon_98704194767% (3)

- Wooley v. Hoffmann-La Roche, IncDokument4 SeitenWooley v. Hoffmann-La Roche, IncAnonymous in4fhbdwkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Regulation Club Licencing FIFA PDFDokument49 SeitenRegulation Club Licencing FIFA PDFAriady ZulkarnainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Memorandum SampleDokument25 SeitenMemorandum SampleganiboyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment & Tariff DeterminationDokument18 SeitenAssessment & Tariff DeterminationMegha0% (1)

- The Place of The Minor in The AdministraDokument22 SeitenThe Place of The Minor in The AdministraRANDAN SADIQNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippines Supreme Court upholds legality of US-RP non-surrender agreementDokument19 SeitenPhilippines Supreme Court upholds legality of US-RP non-surrender agreementJoycelyn Adato AmazonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Principles of TaxationDokument36 SeitenGeneral Principles of Taxationnicole5anne5ddddddNoch keine Bewertungen

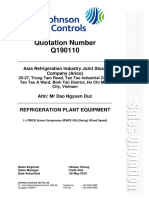

- Q190110 (Rwfii 100)Dokument8 SeitenQ190110 (Rwfii 100)Đạo NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obligations Digests, Civil Law ReviewDokument112 SeitenObligations Digests, Civil Law ReviewMadzGabiolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Process of Organization Development Chapter 4: Entering and ContractingDokument24 SeitenThe Process of Organization Development Chapter 4: Entering and ContractingLaarni Orogo-EdrosoNoch keine Bewertungen