Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Kapolka Cultural Autobiography

Hochgeladen von

api-257190713Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Kapolka Cultural Autobiography

Hochgeladen von

api-257190713Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Running header: MY WHITE CULTURE

Accepting the Realities of My White Culture

Corey Kapolka

Michigan State University

TE 822-301 Summer 2014

MY WHITE CULTURE

I was raised in a comfortably middle-class family. Our family home was located in a

high-quality suburban school district, where I had (mostly) very good teachers in (mostly) wellbehaved classes. I never really wanted for anything materially important in life, though we

werent particularly wealthy. In my schools, some students were noticeably from well-off

families, while others were poor. But almost all of us were the same in one important respect: we

were white.

The boundaries of our district extended only to the limits of the suburbs not into nearby

Grand Rapids city and its urban neighborhoods. Our schools were not intentionally segregated,

but the fact that those neighborhoods which fed into these schools were predominantly inhabited

by white families meant that the student population in the schools could hardly have been

considered racially diverse. For a short period after I began studying in high school, we had rare

few students of color in a school of 1500 students several of whom were adopted into white

families. Soon after, some groups of students from outside of this ethnic monoculture entered the

district at various times, but those that I remember remained isolated within the social structure

of our school.

Shortly after the Bosnian War, our area received a large community of ethnic Bosnian

families fleeing the carnage. Though they could have been considered white, the children of

these families generally stayed within their own ethnic social groups. Differences in language

and upbringing created a perceptible divide between the pre-existing social groups of my school

and those of our newly accepted refugees. Several years later, a similar pattern emerged when

students from neighborhoods within the city of Grand Rapids were bussed to our high school to

enroll. The dominant majority of white middle-class suburban students did not merge well with

this new group. It was not a malicious or even intentional divide; it felt more like a disinterested

MY WHITE CULTURE

neglect. Our racial groups remained comfortably separate, reinforcing through inaction a kind of

modern school segregation.

I was among the students of the dominant white culture who neglected to try to

incorporate these new classmates. At the time, it didnt seem important to intentionally approach

transfer students and include them in social activities or try to become friends. Eventually, I

thought, things would work out and our school would naturally become integrated. That never

really materialized. I, like most of my classmates, remained focused on our own studies and

close social circles. I didnt think anything wrong of that then, which still bothers me today.

Being from a comfortable middle-class family in a good suburban school, I was expected

to succeed in academics. To us, high school was simply preparation for college, and our teachers

were largely of a similar mind. We had siblings and friends with siblings who all went to college,

got decent jobs, and settled into family lives. We saw students portrayed on TV that looked like

us, talked like us, and had aspirations that became ours. We could relate to the struggles of lonely

teenagers and road-tripping friends in movies. We knew what we could be, and we knew that we

could succeed. For many of us, not receiving As and Bs in our classes was horrible, because it

meant that we werent moving along the smooth life path that our parents, teachers, and

television shows said that we would. We had to be good students, because to us, that was the

whole point of being in school.

Since I did not often socialize with races other than my own in high school, the

development of my beliefs, behaviors, mannerisms in a word, my culture was limited to

white culture. We weren't taught much about other cultures beyond a few units in history and

social studies classes. We were taught culture by our parents, by our peers, and by our teachers

all of whom (aside from a select few peers) were white. Looking back, it is rather striking that

MY WHITE CULTURE

none of the teachers at our high school were of any other ethnic or racial group than the

dominant race of the school. Like the neglectful divide between the dominant and introduced

racial groups of our school, I do not believe that our teachers intended to prevent us from

learning the perspectives of other racial groups. But their entire teaching ideologies were built

from within white culture, and so we were not encouraged to critically analyze the role of our

own culture in the struggles of subordinate ones (Sleeter, 2005). The lack of a variety of

experiences and perspectives on racial issues gave us a stunted understanding of racial diversity

and the importance thereof. It wouldn't be until college that I would learn to appreciate

something of the modern struggle of subordinate racial and ethnic groups.

I appreciated in grade school that I did not have a good understanding of racial groups

beyond my own, though I did not realize just how important my racial identity was to my entire

worldview. I did not appreciate just how powerful my racial privilege was because the privileged

culture was really all that I knew. Nearly a decade removed from my secondary schooling, it is

plain to see many privileges that we had that I failed to consider at the time. For instance,

because white Americans tend to be more well-educated and employed than other racial groups,

they can afford to locate their families in districts that are known for quality schools. My own

parents did just that when they were planning to start their family. Within these quality schools

with predominantly white students, study of the culture of the dominant racial group

(white/caucasian) is given a great deal of importance relative to other racial cultures. This is still

largely true even in predominantly non-white schools because the textbooks, teaching materials,

and standards available for those schools are often the very same as for suburban white schools.

Where ever a white student may go, they will find that their racial identity is given a great deal of

weight in their studies (McIntosh, 1989).

MY WHITE CULTURE

Similar to what Olson (1992) observed, as white students in a predominantly white

school we did not need to worry about relating to the racial identities of our teachers and

administrators. Our faculty and staff were staggeringly white, and were members of the

community around our schools. In schools populated by mostly students of color, the proportions

of racial identities of teachers and administrators are often very similar to those of suburban

schools mostly white. But in the context of schools whose students are a mix of black, latino/a,

asian, and white, most of these students have difficulty finding teachers who look like

themselves. They see people in positions of power and knowledge and can get discouraged at the

wild disparity between the demographics of their communities and the makeup of the teachers

who are supposed to help them bridge the racial divide.

Considering the problems that exist in schools with a large disparity between the racial

makeup of the students and that of faculty, I worry that I am perpetuating these problems by

entering teaching as a white educator in urban schools. How can I help bring a greater racial

diversity to the teaching faculty in schools dominated by students of color when I am a white

man? No matter how hard I may push my students to join the profession and become examples

of great teachers for their own future students, my own skin will betray that I am still a part of

the dominant racial group that exerts immense control over secondary education.

But regardless of my worries about my own skin, I will be a teacher in racially diverse

schools. If I cannot expect my students to empathize with me based on my race, I may be able to

instead approach them by accepting some of their own culture, such as subtle language styles, as

my own (Christensen, 2008; Delpit, 1994). In me, they may not see a black man or a Latina

woman, but they may see that many of the ways that they talk and behave that are not typically

'white' are also not unacceptable ways to act. I cannot expect my students to conform to the

MY WHITE CULTURE

standards expected of me at my own high school, because those standards were couched in the

expectations of one particular culture that is not their own. If I can show my students that I do

not look down on their culture, but rather that I am trying to embrace it as far as a teacher can, I

believe that I can begin to bridge the cultural divide between us.

In my schooling, 'gifted' students were identified using standards based on mathematical

and logical skills-based testing. Being raised to excel in these areas, many of us in those schools

qualified for inclusion into the gifted group. But for students who have not been raised and

taught to exceed expectations in the academic areas considered important for the 'gifted'

distinction, their talents can be neglected due to a nearsighted focus on one particular set of skills

rather than considering a wide set of abilities as being special. In racially diverse schools where

teachers have not pushed and prepared their students to think independently and develop a

critical eye for questions, these schools can appear to be full of students who lack the sorts of

special qualities that children in white schools possess. This is not necessarily true - there may be

an abundance of gifted students who are simply not recognized by teachers who are not looking

for them, and many students may simply be gifted with skills that are not included in the

conventional definition of gifted that emanates from suburban schools (Ford, 2010).

As Philipe Ernewein of the Denver Academy advocates, teachers should consider how is

this student smart? rather than how smart is this student? Every student is capable of some

sort of achievement in the classroom; it is the responsibility of their teachers to encourage the

growth of physical and mental skills that are appropriate for each individual student. I want to

teach with this goal in mind. My students may not meet the standards for being 'gifted' that

existed when I was a young student, but they may be capable of artistic, linguistic, or analytical

feats that are not normally associated with giftedness. I want to encourage each of my students to

MY WHITE CULTURE

grow as scientists using their own individual abilities, and not to worry about conforming to

standards of excellence that just aren't relevant for them. In fact, science can often be an artistic

pursuit mathematics and logical reasoning are important, of course, but finding out why the

universe is the way it is takes a great deal of creative thinking.

Teaching in a poor urban setting is not easy, and neither is providing individual

motivation to hundreds of students. But students in high-need urban schools deserve a good

education just as much as students in suburban white-dominated districts, and I know that most

of them appreciate their dedicated teachers. I have worked with many students at Everett and

Eastern High School who made it clear that they did not enjoy school, but their reactions to

individualized teaching showed that they certainly enjoyed learning. If I find that the students in

my classroom resent education but love learning, I will need to teach in such a way that the

educational system that has failed them so far is merely a backdrop for their own learning

processes.

MY WHITE CULTURE

References

Christensen, L. (2008). Putting out the linguistic welcome mat: Honoring students home

language builds an inclusive classroom. Rethinking schools, 23(1), 19-23.

Delpit, L. (1994). Language diversity and learning. In Other peoples children: Cultural

conflict in the classroom (pp. 48-69). New York: The New Press.

Ford, D. Y. (2010). Recruiting and retaining gifted students from diverse ethnic, cultural, and

language groups. In J. Banks and C. A. Banks (Eds.), Multicultural education, 7th

edition (pp. 371-391). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

McIntosh, P. (1989, July/August). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. Peace

and Freedom, 10-12.

Olson, R. A. (1992). White privilege in schools. Staff, Family, and Community, 83-84.

Sleeter, C. E. (2005). Teachers beliefs about knowledge. In Un-standardizing curriculum:

Multicultural teaching in the standards-based classroom (pp. 28-42). New

York, Teachers College Press.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Tao Te Ching, W. BynnerDokument26 SeitenTao Te Ching, W. BynnerariainvictusNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Principles in Life (Essay Sample) - Academic Writing BlogDokument3 SeitenMy Principles in Life (Essay Sample) - Academic Writing BlogK wongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kapolka 15te804 Learningstory1Dokument12 SeitenKapolka 15te804 Learningstory1api-257190713Noch keine Bewertungen

- Myp Pedigree Lesson PlanDokument2 SeitenMyp Pedigree Lesson Planapi-257190713Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ckapolka Resume 4 10 15Dokument2 SeitenCkapolka Resume 4 10 15api-257190713Noch keine Bewertungen

- DP Biology - Speciation Lesson PlanDokument2 SeitenDP Biology - Speciation Lesson Planapi-257190713100% (1)

- Myp Quiz 4 - PhotosynthesisDokument2 SeitenMyp Quiz 4 - Photosynthesisapi-257190713Noch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 4 ObjectivesDokument1 SeiteUnit 4 Objectivesapi-257190713Noch keine Bewertungen

- Myp Biology Genetics ExamDokument8 SeitenMyp Biology Genetics Examapi-257190713100% (1)

- Cell Biology ActivityDokument7 SeitenCell Biology Activityapi-257190713Noch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 3 ObjectivesDokument1 SeiteUnit 3 Objectivesapi-257190713Noch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 2 ObjectivesDokument1 SeiteUnit 2 Objectivesapi-257190713Noch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 1 ObjectivesDokument1 SeiteUnit 1 Objectivesapi-257190713Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cell Biology Test Study GuideDokument2 SeitenCell Biology Test Study Guideapi-257190713100% (1)

- Ckapolka ResumeDokument3 SeitenCkapolka Resumeapi-257190713Noch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurial Self TestDokument2 SeitenEntrepreneurial Self TestAngge CortesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Exercise 3 STS 2021Dokument6 SeitenPractice Exercise 3 STS 2021Tiana NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brave New World Web QuestDokument3 SeitenBrave New World Web QuestΑθηνουλα ΑθηναNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basarab Nicolescu, The Relationship Between Complex Thinking and TransdisciplinarityDokument17 SeitenBasarab Nicolescu, The Relationship Between Complex Thinking and TransdisciplinarityBasarab Nicolescu100% (2)

- Medieval TortureDokument7 SeitenMedieval TortureCarolina ThomasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Candidate Assessment Activity: Written Responses To QuestionsDokument2 SeitenCandidate Assessment Activity: Written Responses To Questionsmbrnadine belgica0% (1)

- 21 Century Success Skills: PrecisionDokument13 Seiten21 Century Success Skills: PrecisionJoey BragatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quality GurusDokument39 SeitenQuality GurusShubham TiwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organizational Commitment and Intention To Leave: Special Reference To Technical Officers in The Construction Industry - Colombo, Sri LankaDokument47 SeitenOrganizational Commitment and Intention To Leave: Special Reference To Technical Officers in The Construction Industry - Colombo, Sri Lankadharul khairNoch keine Bewertungen

- Course BookDokument15 SeitenCourse BookSinta NisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1402-Article Text-5255-2-10-20180626Dokument5 Seiten1402-Article Text-5255-2-10-20180626Rezki HermansyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Formal PresentationDokument5 SeitenFormal PresentationMuhammad Ali Khalid100% (1)

- Hector Cruz, Matthew Gulley, Carmine Perrelli, George Dunleavy, Louis Poveromo, Nicholas Pechar, and George Mitchell, Individually and on Behalf of All Other Persons Similarly Situated v. Benjamin Ward, Individually and in His Capacity as Commissioner of the New York State Department of Correctional Services, Vito M. Ternullo, Individually and in His Capacity as Director of Matteawan State Hospital, Lawrence Sweeney, Individually and in His Capacity as Chief of Psychiatric Services at Matteawan State Hospital, 558 F.2d 658, 2d Cir. (1977)Dokument15 SeitenHector Cruz, Matthew Gulley, Carmine Perrelli, George Dunleavy, Louis Poveromo, Nicholas Pechar, and George Mitchell, Individually and on Behalf of All Other Persons Similarly Situated v. Benjamin Ward, Individually and in His Capacity as Commissioner of the New York State Department of Correctional Services, Vito M. Ternullo, Individually and in His Capacity as Director of Matteawan State Hospital, Lawrence Sweeney, Individually and in His Capacity as Chief of Psychiatric Services at Matteawan State Hospital, 558 F.2d 658, 2d Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- SF2 LACT 3 Teacher NanDokument5 SeitenSF2 LACT 3 Teacher NanLignerrac Anipal UtadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Barriers of CommunicationDokument2 SeitenCultural Barriers of CommunicationAndré Rodríguez RojasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sonnets of E.E CummingsDokument25 SeitenSonnets of E.E CummingsJonathan DubéNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science Webquest LessonDokument5 SeitenScience Webquest Lessonapi-345246310Noch keine Bewertungen

- Top Survival Tips - Kevin Reeve - OnPoint Tactical PDFDokument8 SeitenTop Survival Tips - Kevin Reeve - OnPoint Tactical PDFBillLudley5100% (1)

- Subject Offered (Core and Electives) in Trimester 3 2011/2012, Faculty of Business and Law, Multimedia UniversityDokument12 SeitenSubject Offered (Core and Electives) in Trimester 3 2011/2012, Faculty of Business and Law, Multimedia Universitymuzhaffar_razakNoch keine Bewertungen

- June 2010 MsDokument24 SeitenJune 2010 Msapi-202577489Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gender (Sexual Harassment) EssayDokument2 SeitenGender (Sexual Harassment) EssayTheriz VelascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developing The Leader Within You.Dokument7 SeitenDeveloping The Leader Within You.Mohammad Nazari Abdul HamidNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1D Used To and WouldDokument2 Seiten1D Used To and Wouldlees10088Noch keine Bewertungen

- Arlene Religion 8Dokument1 SeiteArlene Religion 8Vincent A. BacusNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 Silabus Population Development and Social ChangeDokument8 Seiten2013 Silabus Population Development and Social ChangeGajah MadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Political DoctrinesDokument7 SeitenPolitical DoctrinesJohn Allauigan MarayagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impacto de Influencers en La Decisiónde CompraDokument17 SeitenImpacto de Influencers en La Decisiónde CompraYuleisi GonzalesNoch keine Bewertungen

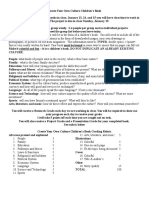

- Create Your Own Culture Group ProjectDokument1 SeiteCreate Your Own Culture Group Projectapi-286746886Noch keine Bewertungen