Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Wagashi

Hochgeladen von

Bookturnal PlaceOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Wagashi

Hochgeladen von

Bookturnal PlaceCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Wagashi and the Japanese Tradition

of Hospitality

In the last few years, the English term sweets has come to be used in Japanese as

a hold-all term referring to all kinds of cakes and confectionary. But it seems a

shame to lump the Japanesewagashi traditionally served with tea into the same

category. They have a special role in social ritual that makes them quite different.

This spring, I took part in a round-table on the subject of traditional Japanese

confectionary culture with the proprietors and artisans of some of Kyotos oldest

traditional wagashi shops. The colors and forms of the wagashi are inspired by

motifs celebrating the beauties of nature. The artistry and attention to detail that goes

into making them is truly remarkable. The artisans who create these edible works of

art somehow manage to impart into the wagashi the very essence of the seasons

mountains, fields, rivers, and lakes. You can almost feel the wind and light of the time

of year. The artisans have an uncanny sensitivity to nature, and live in intimate

proximity with the changing seasons.

During the round table, one wagashi maker explained that Traditional wagashi are

much more than simply a sweet snack. There are part of a culture of hospitality, with

its precise etiquette and traditions. In Kyoto, the host washes down the area in front

of the house and lights incense in the entrance porch in anticipation of a visit. The

ground mustnt be either too wet or too dry when the guest arrives. If the incense is

lit too soon, the scent will have disappeared by the time the guest arrives. But if the

smoke is still rising when the guest arrives, that is a discourtesy too. Timing is

essential. The host arranges a selection of seasonal flowers, and hangs a scroll with

some kind of relevance to the season, the expected guest, or the topic to be

discussed.

Wagashi and the Aesthetics of Minimalism

When the guest arrives the host serves tea, and then it is time for the wagashi to

make their appearance. Seasonal motifs are used in the wagashi, as well as elegant

poetic names. The guest will normally start by admiring the beauty of the design, and

then ask about the name of thewagashi. This provides a topic for conversation. Many

of the names allude to lines from classical literature. Finally, the guest raises

the wagashi to her lips. First one enjoys the wagashi with the eyes. Next comes the

imaginative enjoyment of the allusions evoked by the nameonly then does one

enter the world of flavor. The wagashi is not something to be scoffed down as soon

as it appears. It is a sophisticated pleasure for mature adults, resonant with the

empty space of the Japanese minimalist aesthetic.

Cherry Blossoms Against the Sunlight

The final stage in the ritual of hospitality is the farewell. In Kyoto, it is common in

private homes and restaurants alike for the host to remain on the threshold until the

guests are out of sight. Hospitality in Japan is the crystallization of many aspects of

Japanese culture: courtesy, consideration, and respect for others, along with an

esthetic enjoyment of nature and the changing seasons, and a culture that esteems

empty space. As part of such an intricate culture of hospitality, it doesnt seem right

to refer to traditional wagashi with a common catch-all term like sweets.

One spring day almost 20 years ago, I came across a beautiful example of the

Japanese confectioners art in a traditional old shop in Kyoto. It was made of sweet

white bean paste wrapped in a soft mochi coating called gyhi. I asked about the

name. Urazakura, the owner told me. Cherry blossoms against the backlit sun. He

explained that the pink color of the confection was reminiscent of the sunlight shining

translucent through cherry blossom petals. Such subtlety and depth! In the years

passed since, I have often remembered the hidden beauty of those cherry blossoms

against the sunlight, symbol of Japanese beauty.

(Originally written in Japanese on May 8, 2013.)

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Myths of China and Japan with illustrations in colour & monochrome after paintings and photographsVon EverandMyths of China and Japan with illustrations in colour & monochrome after paintings and photographsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Perfect Tagine Cookbook; The Complete Nutrition Guide To Moroccan One-Pot Tagine Culinary With Delectable And Nourishing RecipesVon EverandThe Perfect Tagine Cookbook; The Complete Nutrition Guide To Moroccan One-Pot Tagine Culinary With Delectable And Nourishing RecipesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Living Buddhism: Mind, Self, and Emotion in a Thai CommunityVon EverandLiving Buddhism: Mind, Self, and Emotion in a Thai CommunityBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (3)

- Sapa, Apa, Mana or Who, What, Where: Baba Malay TodayVon EverandSapa, Apa, Mana or Who, What, Where: Baba Malay TodayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wagashi - Jo-Namagashi - Nerikiri RecipeDokument9 SeitenWagashi - Jo-Namagashi - Nerikiri RecipeDavid100% (1)

- The Book of TeaDokument49 SeitenThe Book of TeawootszhinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Food Culture of Kansai and Kanto5Dokument12 SeitenFood Culture of Kansai and Kanto5Hans Morten Sundnes100% (1)

- Seoul HiSeoul Best Korean RestaurantsDokument97 SeitenSeoul HiSeoul Best Korean RestaurantsAnonymous XgX8kT100% (1)

- KOREA (2012 VOL.8 No.11)Dokument28 SeitenKOREA (2012 VOL.8 No.11)Republic of Korea (Korea.net)100% (3)

- Korean FoodsDokument15 SeitenKorean FoodsStephanie JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moritsuke Reference TSUDOI FB 2020Dokument3 SeitenMoritsuke Reference TSUDOI FB 2020ColletNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calendar of The Gods in ChinaDokument62 SeitenCalendar of The Gods in Chinadelphic78Noch keine Bewertungen

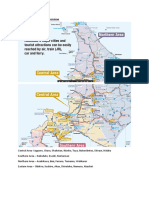

- Hokkaido 8D7N ItineraryDokument29 SeitenHokkaido 8D7N ItineraryGan Sze HanNoch keine Bewertungen

- UIC Newsletter: Spring 2024Dokument56 SeitenUIC Newsletter: Spring 2024Underwood International College100% (1)

- Highways and Homes of Japan PDFDokument564 SeitenHighways and Homes of Japan PDFEdwin Arce II100% (1)

- Yūgen and The Poetics of The Shinkokinshū PeriodDokument6 SeitenYūgen and The Poetics of The Shinkokinshū PeriodfavillescoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Basic Guide To Food PresentationDokument17 SeitenA Basic Guide To Food Presentationwhims varunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Japanese Cuisine - FinalDokument43 SeitenJapanese Cuisine - Finaldennis artugue100% (2)

- Japanese Food Presentation and Styling TechniquesDokument12 SeitenJapanese Food Presentation and Styling TechniquesAabhas Mehrotra100% (2)

- KOREA Magazine (DECEMBER 2011 VOL. 8 NO. 12)Dokument29 SeitenKOREA Magazine (DECEMBER 2011 VOL. 8 NO. 12)Republic of Korea (Korea.net)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Maangchi's Big Book of Korean Cooking: From Everyday Meals To Celebration Cuisine - MaangchiDokument5 SeitenMaangchi's Big Book of Korean Cooking: From Everyday Meals To Celebration Cuisine - MaangchijojasoleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Masterclass in MatchaDokument39 SeitenMasterclass in MatchatomasiskoNoch keine Bewertungen

- UKS11 Korean Cuisine EngDokument88 SeitenUKS11 Korean Cuisine EngParkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ikigai Diet The Secret of Japanese Diet To Health and Longevity (Sachiaki Takamiya)Dokument44 SeitenIkigai Diet The Secret of Japanese Diet To Health and Longevity (Sachiaki Takamiya)Gorki La TorreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chinese Calligraphy PDFDokument9 SeitenChinese Calligraphy PDFEm100% (1)

- Lobal EA UT: Tea UtensilsDokument48 SeitenLobal EA UT: Tea UtensilsHoàng Như Nguyễn100% (1)

- Zen & Tea: Lobal EA UTDokument48 SeitenZen & Tea: Lobal EA UTHoàng Như NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Korean SpiritualityDokument186 SeitenKorean SpiritualityrqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Japanese Arts: Company NameDokument44 SeitenJapanese Arts: Company NamePrincess Loraine DuyagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buddhism Japanese AestheticsDokument11 SeitenBuddhism Japanese Aestheticsanarcistic100% (1)

- Traditional craftsmanship in Japan - The Art of ImperfectionVon EverandTraditional craftsmanship in Japan - The Art of ImperfectionNoch keine Bewertungen

- KisetsuTheJapanesesenseoftheseasons ETdoc250208Dokument2 SeitenKisetsuTheJapanesesenseoftheseasons ETdoc250208RNoch keine Bewertungen

- Top Japanese CultureDokument11 SeitenTop Japanese CultureReynalynne Caye MagbooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eating India: An Odyssey into the Food and Culture of the Land of SpicesVon EverandEating India: An Odyssey into the Food and Culture of the Land of SpicesBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (24)

- Art of Chabana: Flowers for the Tea CeremonyVon EverandArt of Chabana: Flowers for the Tea CeremonyBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Exploring the World of Japanese Craft Sake: Rice, Water, EarthVon EverandExploring the World of Japanese Craft Sake: Rice, Water, EarthNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blossoms and Stones : Understanding Symbolism in Japanese GardensVon EverandBlossoms and Stones : Understanding Symbolism in Japanese GardensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Japanese TraditionDokument1 SeiteJapanese TraditionDiana Mae SudarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wabi Sabi: Japanese Wisdom for a Perfectly Imperfect LifeVon EverandWabi Sabi: Japanese Wisdom for a Perfectly Imperfect LifeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (12)

- Chado the Way of Tea: A Japanese Tea Master's AlmanacVon EverandChado the Way of Tea: A Japanese Tea Master's AlmanacBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- A Little Book of Japanese Contentments: Ikigai, Forest Bathing, Wabi-sabi, and MoreVon EverandA Little Book of Japanese Contentments: Ikigai, Forest Bathing, Wabi-sabi, and MoreBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (11)

- Tea Ceremony: The Way of TeaDokument4 SeitenTea Ceremony: The Way of TeaMarie Anne Bachelor100% (1)

- Harmony in Nature Exploring the Japanese ConnectionVon EverandHarmony in Nature Exploring the Japanese ConnectionNoch keine Bewertungen

- H ChawansDokument3 SeitenH Chawansanon-465023Noch keine Bewertungen

- Japanese Sake Bible: Everything You Need to Know About Great Sake (With Tasting Notes and Scores for Over 100 Top Brands)Von EverandJapanese Sake Bible: Everything You Need to Know About Great Sake (With Tasting Notes and Scores for Over 100 Top Brands)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ikebana - The Art of Flower Arrangement - Ikenobo SchoolVon EverandIkebana - The Art of Flower Arrangement - Ikenobo SchoolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Japan Travel GuideDokument20 SeitenJapan Travel GuideWilroseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summative Test Arts 8Dokument1 SeiteSummative Test Arts 8Jefray OmongosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elements of Japanese DesignDokument17 SeitenElements of Japanese DesignLinneferNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nintendo of America Inc. P.O. Box 957, Redmond, WA 98073-0957 U.S.ADokument18 SeitenNintendo of America Inc. P.O. Box 957, Redmond, WA 98073-0957 U.S.AsuperwakkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Women Warriors of Japan - The Japan TimesDokument10 SeitenWomen Warriors of Japan - The Japan TimesAshley StarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ryūteki: Otsuzumi. They Are Used in BothDokument5 SeitenRyūteki: Otsuzumi. They Are Used in BothCassandra LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mayumi Et Al-2018-Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic SciencesDokument5 SeitenMayumi Et Al-2018-Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic SciencesAndres RiveraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1474519157780Dokument66 Seiten1474519157780MarksdwarfNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brosur Meja Operasi PDFDokument8 SeitenBrosur Meja Operasi PDFkartikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Japanese PsycheDokument3 SeitenThe Japanese PsycheLorena OtaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Occhi, Debra J. 2012 Wobbly Aesthetics, Performance, and Message: Comparing Japanese Kyara With Their Anthropomorphic Forebears. Asian Ethnology 71:1, 109-132.Dokument24 SeitenOcchi, Debra J. 2012 Wobbly Aesthetics, Performance, and Message: Comparing Japanese Kyara With Their Anthropomorphic Forebears. Asian Ethnology 71:1, 109-132.15strawberryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Traditional Japanese Stair CabinetDokument12 SeitenTraditional Japanese Stair CabinetNoemi González100% (1)

- The Languages of Japan-1-200Dokument200 SeitenThe Languages of Japan-1-200XivdusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samurai ReadingDokument3 SeitenSamurai ReadingAnabel VarelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iwrbs 3Dokument36 SeitenIwrbs 3nhfdbhddhsdeyterhguyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Significance of The Number NineDokument1 SeiteSignificance of The Number NineJoão VictorNoch keine Bewertungen

- JLPT N5 Grammar Master Ebok by JLPTsensei - Com PreviewDokument12 SeitenJLPT N5 Grammar Master Ebok by JLPTsensei - Com PreviewPankaj SahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Japanese Fish KillingDokument19 SeitenJapanese Fish KillingPrashantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Collins Easy Learning Japanese BookletDokument48 SeitenCollins Easy Learning Japanese BookletAdriana Tbk100% (1)

- Fola TimeDokument31 SeitenFola TimemaizeeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accounts Lesson Plan 2Dokument4 SeitenAccounts Lesson Plan 2hitesh anilkumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- LIST ANIME WINTER 2014 (Januari-Maret 2014) NO ( (TV Series) )Dokument19 SeitenLIST ANIME WINTER 2014 (Januari-Maret 2014) NO ( (TV Series) )Arief MunandarNoch keine Bewertungen

- KamakuraDokument3 SeitenKamakuraGeorg GergiouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shiho S. Nunes, Sara Nunes-Atabaki - The Shishu Ladies of Hilo - Japanese Embroidery in Hawai'i (1999, University of Hawaii Press)Dokument156 SeitenShiho S. Nunes, Sara Nunes-Atabaki - The Shishu Ladies of Hilo - Japanese Embroidery in Hawai'i (1999, University of Hawaii Press)onecolorNoch keine Bewertungen

- L5R 1e - S2 Twilight HonorDokument52 SeitenL5R 1e - S2 Twilight HonorCarlos William LaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of The Grading System - DR M Callan 30may15 For BJADokument47 SeitenHistory of The Grading System - DR M Callan 30may15 For BJAcuradarsjrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Japanese Sentence Patterns For JLPT N5 Training Book (Japanese Sentence Patterns Training Book 1) (Noboru Akuzawa)Dokument202 SeitenJapanese Sentence Patterns For JLPT N5 Training Book (Japanese Sentence Patterns Training Book 1) (Noboru Akuzawa)KrasynskyiNoch keine Bewertungen

- j30 AnswerkeyDokument17 Seitenj30 AnswerkeysaintpandoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- USKF Black Belt Hall of Fame To Induct Grand Master Eddie MinyardDokument2 SeitenUSKF Black Belt Hall of Fame To Induct Grand Master Eddie MinyardPR.comNoch keine Bewertungen