Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Retallack's Notion of The Experimental Feminine in Rachel Blau DuPlessis's"Family, Sexes, Psyche: An Essay On H.D. and The Muse of The Woman Writer".

Hochgeladen von

May SyedaOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Retallack's Notion of The Experimental Feminine in Rachel Blau DuPlessis's"Family, Sexes, Psyche: An Essay On H.D. and The Muse of The Woman Writer".

Hochgeladen von

May SyedaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Syeda 1

MaySyeda

ProfessorAmyRobbins

ENGL319.75WomenandtheAvantGarde

Analysispaperassignment

Due:10/25/12

Retallacks Notion of the Experimental Feminine in Rachel Blau DuPlessissFamily, Sexes,

Psyche: An Essay on H.D. and the Muse of the Woman Writer.

In her essay The Experimental Feminine, Joan Retallack calls for a grammar that

counters the empty form of mainstream narratives and resists habituated responses (78). The

experimental feminine, as a grammar, embraces the illogical and the unintelligible as a means

of resistance to a dominant culture that works to subjugate the feminine unintelligible by a

masculine logic. The experimental feminine is conceptually separate from the sexed body and

can be enacted by anyone on the gender spectrum. Rachel Blau DuPlessiss essay Family,

Sexes, Psyche: An Essay on H.D. and the Muse of the Woman Writer challenges the

conventions of the traditional critical essay by embracing a feminine dyslogic. DuPlessis is a

poet-critic and her critical essay on the poet H.D. is informed by and in conversation with her

own identity as a woman poet. She infuses her critical essay with experimental syntax, poetic

language, autobiography and shifting authorial voices. The form of her critical essay works

concurrently with its exploration of H.D.s struggle to disrupt the status-quo models of gender

and sexuality through her career as a women poet and creatively stifled poetess. It is

unintelligible as a critical essay but intelligible as an avant-gardist text. DuPlessis disrupts the

form of the academic essay to achieve a dyslogical feminist aesthetic.

Syeda 2

DuPlessiss essay works in opposition to the masculine objectives of the academic critical

essay which are to theorize, hypothesize, characterize and achieve a logical order. Montaigne,

the father of the essay, imbues the form with feminine traits like incoherence and inconsistency

(Retallack 94). The original spirit of the essay is diluted by the dominant cultures academia.

Twentieth-century avant-gardists began to experiment with form as answer and art-object rather

than as the promise of an answer or the forbearer of the art-object. As an avant-garde practice,

DuPlessis embraces the essay as a space for investigation and not the documented results of an

extra-textual investigation. Her essay is a site of struggle and reads incoherent in its openness

to its inability to conclude (Retallack 98). DuPlessiss essay breaks with syntactical

conventions to avoid a clear, logical progression and it reads as if she does not know to what

conclusion she will arrive by the end of the essay. In embracing the unintelligible she creates a

space for new meaning to emerge through shifting associations and identities rather than an

imposition of meaning or a control of identity.

DuPlessis uses poetic conventions and poetical syntax throughout Family, Sexes,

Psyche, defying the formal syntax of a critical paper. Examples of her alternate syntactical

conventions include frequent line breaks, sentence fragments, short paragraphs, single-line

paragraphs, page breaks, and the use of empty space to frame emotionally charged lines. As

illustrated by the soldier in La Belle Dame Sans Merci, men determine the narrative.

DuPlessis uses wordplay to emphasize womens need to take control of their story. De-story?

Destory? and lever lover. She makes a list of the central struggles of the woman writer and

in the next one-line paragraph she simply states All must be re-made (25). By setting it apart

with empty space she creates a silence in which the unintelligible can be heard and repeats this

Syeda 3

technique throughout the essay. The use of poetical syntax serves to re-make the structure of the

critical essay as an experimental space.

DuPlessis uses poetic language and repeats the image of woman as rock throughout the

essay. Through this repetition she reaches for a new understanding of women by creating new

associations. She starts with the line No, my poetry was not dead but it was built on or around

the crater of an extinct volcano, from H.D.s End to Torment. This line is repeated and then

extended into other rock-images. This essay is about a woman, so there is a rock (DuPlessis

30). She speaks of men eroding voice, a term with geological connotations. She creates

associative meaning by speaking of women in relation to Rodins statue Thought and the

immovable Sphynx with the stone vulval lips. The Thinker sits on a rock. Thought

emerges. She emerges or is sinking. She is self and rock (DuPlessis 39). The essay ends with

images of volcanic rock, women as rock, buried to the neck but born up through the glottal

inelegant column (DuPlessis 40). Women are rock and buried by layers of rock (the extinct

volcano), but through their voice they can free themselves out from under the geologic ruin and

into the world. The lyrical sequences in DuPlessiss critical essay give the text a valence that

cuts into the bone of the reader, conveying the urgency of the ongoing struggle that is the life of

the woman poet. The use of the lyric in the critical essay works to create emotionally charged

associative meanings that straight academic prose would fail to do. The lyric form is feminine in

the way it allows for a multiplicity of interpretations rather than imposing any one meaning on to

the reader.

DuPlessis uses several voices throughout her essay including the voice of the academic,

the voice of the woman-poet, the voice of her subjects, and the voice of Rachel Blau DuPlessis

herself. Traditional critical essays maintain an unwavering academic voice that is a distant and

Syeda 4

impassioned vehicle for an argument supported by direct textual analysis. The unstable voice of

her essay accounts for a multiplicity of identity that simultaneously defies the masculine logic

and embraces the feminine dyslogic. The essay begins in the voice of the academic that states

the essays attempt to explore the cultural problems posed by H.D.s male sexual attachments.

This academic voice, however, is quickly destabilized with the line Im telling you what to do,

now do it! which is DuPlessis adopting the voice of D.H. Lawrences character Rico in Bid Me

To Live. Further down, the line Not rigor morits. No, No.! (21) is separated by blank space,

framing it in silence and giving it a weight that demands consideration. This line can be read as

the voice of H.D. or DuPlessiss own voice as a woman-poet fighting against the dominant

cultures myth of the dead woman-poet who does as commanded. What does a woman do who

will be a poet? Those from whom you stand to learn the most can also destroy you. /I flee from

them. She asks that of both H.D. and herself and the response of I flee from them is

understood as both her voice and H.D.s voice. This situates the text as not just a critical essay

on H.D. but an essay in which DuPlessis explores her own identity as a woman-poet in a

patriarchal society. As H.D. fled from Pound, DuPlessis fled from male mentors in university

(Frost 106). She combines the voices of H.D. and herself with the line That I am inside the

truck. I am the highway of my own repression (28). In the next paragraph she shifts into the

autobiographical I of Rachel Blau DuPlessis in the passage that begins On my desk, Capulin

Mountain and shifts back to H.D. by echoing the line from End of Torment. The shifting

identity of the authorial I gives life to the struggle on the page. The career of the woman poet

is the career of that struggle; to resist being reduced to either muse or poetess. H.Ds struggle is

DuPlesssiss struggle is the struggle of every woman poet.

Syeda 5

As the feminine cannot exist without the masculine, there is a final attempt towards logic.

But that logic gives way to dyslogic. DuPlessis rejects the idea of the male-muse for the womanpoet but when she concludes the family is the women-poets muse it is unclear if she means the

traditional heteronormative structure of family or the structure in which the woman-poet creates

her own family. Can the Janus-faced doors of parents and sexuality be unhinged by adopting a

sexuality that resists classification and resists classifying any one person as lover, husband, wife,

mother, father, brother, sister, child, cousin, uncle, aunt, and so forth? Can it be done? DuPlessis

recognizes that H.D.s long and close relationship to Winfried Bryher, which cycled through

periods of sexual activity and inactivity, did not serve as a satisfactory solution to her sexual

desire for men (DuPlessis 20). Does the erotic cupid that is her imagined child with Pound

satisfy the role of muse to the woman poet? The meaning of her argument is open to

interpretationvague, unclear, unintelligiblethe embodiment of the experimental feminine.

Rachel Blau DuPlessiss Family Sexes Psyche, features a weaving in and out to form

an argument lacking tensile strength. It is unable to hold up against its own weight. The

tenuousness of meaning allows for a multiplicity of meaning through associations and reassociations, embracing Retallacks notion of the experimental feminine. The essay is chaotic,

disordered, and frustrating to read as a critical essay. It does not satisfy under the rules of

dominant culture. It does not present a clear linear argument but allows for meanings to emerge

gradually through unstable associations. The essay is an embodiment of struggle. The poetic

conventions work to embody a tension as frustrating and revolutionary as water flowing

upwards. She does not burn the myth of the woman as muse and summon a new muse from its

ashes but attempts to destabilize the myth and form new associations through a new grammar.

DuPlessis uses this essay to reach for a new feminist aesthetic and the unintelligible becomes a

Syeda 6

new way of engaging with the world rather than a problem that needs to be solved or

incorporated into a logical, masculine framework.

Works Cited

DuPlessis, Rachel Blau. The Pink Guitar: Writing as Feminist Practice. Tuscaloosa:

Univeristy of Alabama Press, 2006. Print.

Frost, Elisabeth A., and Cynthia Hogue, eds. innovative women poets: an anthology of

contemporary poetry and interviews. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2006. Print.

Retallack, Joan. The Poethical Wager. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003. Print.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Exposing Jewish Lies About HitlerDokument10 SeitenExposing Jewish Lies About HitlerAndrew Miller60% (5)

- Anal Sex With My WifeDokument8 SeitenAnal Sex With My WifeSGoud0% (1)

- Turas Math DhutDokument52 SeitenTuras Math DhutAnonymous WUSxJ3rNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pride Prejudice Teacher GuideDokument32 SeitenPride Prejudice Teacher GuideGriselda Delvo100% (2)

- Cimino DiaryDokument767 SeitenCimino Diarycgreen2877100% (1)

- The Beatles and The Mind ControlDokument2 SeitenThe Beatles and The Mind Controlalejandrocolon100% (2)

- Tolstoy or Dostoevsky: An Essay in the Old CriticismVon EverandTolstoy or Dostoevsky: An Essay in the Old CriticismBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (17)

- Psychosexual TheoryDokument27 SeitenPsychosexual Theoryrejeneil100% (1)

- Ted Hughes As A Modern PoetDokument5 SeitenTed Hughes As A Modern PoetMehar Waqas Javed67% (3)

- Rothschild FamilyDokument31 SeitenRothschild Familyfeeamali1445100% (1)

- Quentin TarantinoDokument160 SeitenQuentin TarantinoNinoska Marquez Romero100% (1)

- Affiavit of Single Parent (Teresita DayagDokument2 SeitenAffiavit of Single Parent (Teresita DayagRey BaltazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ma Pyu An Arakanese Love Story (First Burmese Novel in Burmese Literature History)Dokument64 SeitenMa Pyu An Arakanese Love Story (First Burmese Novel in Burmese Literature History)Moe Ma Ka100% (2)

- Omniscience in FictionDokument20 SeitenOmniscience in FictionMark J. Burton IINoch keine Bewertungen

- Jane EyreDokument131 SeitenJane Eyreadariadna100% (5)

- Analyzing Ecriture Feminine in "The Laugh of The Medusa"Dokument10 SeitenAnalyzing Ecriture Feminine in "The Laugh of The Medusa"Roxana Daniela AjderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Am No 02 1 19 SC Commitment of Children PDFDokument6 SeitenAm No 02 1 19 SC Commitment of Children PDFHaniyyah Ftm0% (1)

- Ariel by Sylvia Plath - Teacher Study GuideDokument1 SeiteAriel by Sylvia Plath - Teacher Study GuideHarperAcademicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freud FetishismDokument1 SeiteFreud FetishismMarianna KayeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feminist Discourse Bell JarDokument15 SeitenFeminist Discourse Bell JarÍtalo CoutinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparative Analysis of Helene Cixous and Virginia WoolfDokument4 SeitenA Comparative Analysis of Helene Cixous and Virginia WoolfBelma SarajlićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing and Deconstruction of Classical TalesDokument4 SeitenWriting and Deconstruction of Classical TalesEcho MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparative Review of ArticlesDokument3 SeitenA Comparative Review of ArticlesMian M Aqib SafdarNoch keine Bewertungen

- InterpretingRevisionistMythMaking CAD WorldsWife PDFDokument7 SeitenInterpretingRevisionistMythMaking CAD WorldsWife PDFAnandini MitraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hubert Preface-L'Esprit Créateur, Volume 29, Number 3, Fall 1989Dokument8 SeitenHubert Preface-L'Esprit Créateur, Volume 29, Number 3, Fall 1989Anonymous NtEzXrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shanlax International Journal of English: AbstractDokument8 SeitenShanlax International Journal of English: Abstractnishant morNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hélène CixousDokument3 SeitenHélène CixousCorina LupsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LURe Fall2012Dokument106 SeitenLURe Fall2012Mohammed TupacyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sedgwick ReviewBetween Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial DesireDokument7 SeitenSedgwick ReviewBetween Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial DesireMohamadNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Spivaks EchoDokument19 SeitenOn Spivaks Echozuza_ladygaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AlexanderDokument21 SeitenAlexandersalomonmarinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feminism and Deconstruction Ms. en Abyme2Dokument4 SeitenFeminism and Deconstruction Ms. en Abyme2Aprilo DielovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feminism and ShakespeareDokument4 SeitenFeminism and ShakespeareCarlos Rodríguez RuedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.format - Hum-A Study On The Characterizaton of Women in Shashi Deshpandey's NovelsDokument6 Seiten1.format - Hum-A Study On The Characterizaton of Women in Shashi Deshpandey's NovelsImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mrs Dalloway Annotated Bibliography - Meghan MillerDokument6 SeitenMrs Dalloway Annotated Bibliography - Meghan Millerdana ANoch keine Bewertungen

- Will and WilleDokument5 SeitenWill and WillebenhjorthNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World's Wife's Personas Through The Psychoanalytic Lens: An Analysis of Mrs. Beast, Mrs. Lazarus, Mrs. Midas, Mrs. Quasimodo and Queen HerodDokument10 SeitenThe World's Wife's Personas Through The Psychoanalytic Lens: An Analysis of Mrs. Beast, Mrs. Lazarus, Mrs. Midas, Mrs. Quasimodo and Queen HerodIJELS Research JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper On Confessional PoetryDokument4 SeitenResearch Paper On Confessional Poetryafmdaludb100% (1)

- Nowhere or Somewhere Dis Locating GendeDokument21 SeitenNowhere or Somewhere Dis Locating Gendeghonwa hammodNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Journal on Multicultural Literature (IJML): Vol. 6, No. 2 (July 2016)Von EverandInternational Journal on Multicultural Literature (IJML): Vol. 6, No. 2 (July 2016)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Political Correctness: Deconstruction and LiteratureDokument6 SeitenPolitical Correctness: Deconstruction and LiteratureEdwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Politics of Language in Helene Cixous' La - The: (Feminine)Dokument5 SeitenPolitics of Language in Helene Cixous' La - The: (Feminine)farida nurulNoch keine Bewertungen

- CC 11Dokument9 SeitenCC 11PurpleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper Proposal American Literature: Surname:1Dokument2 SeitenPaper Proposal American Literature: Surname:1Sammy GitauNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Investigation of La Voix Et Le PhénomèneDokument34 SeitenAn Investigation of La Voix Et Le Phénomèneegryu9381Noch keine Bewertungen

- "To Be, or Not To Be, Is Still The Question": Identity and "Otherness" in D. H. Lawrence's WorkDokument14 Seiten"To Be, or Not To Be, Is Still The Question": Identity and "Otherness" in D. H. Lawrence's WorkGeli GestidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Glossary of Terms PDFDokument5 SeitenGlossary of Terms PDFnissan8852Noch keine Bewertungen

- Creating "The Second Self": Performance, Gender, and AuthorshipDokument9 SeitenCreating "The Second Self": Performance, Gender, and AuthorshipÉrika VitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading & Writing (As) Woman 2Dokument25 SeitenReading & Writing (As) Woman 2Noelle Leslie Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kamala Das PoemsDokument14 SeitenKamala Das PoemsAastha SuranaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 751-755 Mano Ranjani. G.MDokument5 Seiten751-755 Mano Ranjani. G.MOnkar DeshmukhNoch keine Bewertungen

- CixousDokument5 SeitenCixousIulia FasieNoch keine Bewertungen

- (16737423 - Frontiers of Literary Studies in China) Beyond Boundaries - Women, Writing, and Visuality in Contemporary ChinaDokument6 Seiten(16737423 - Frontiers of Literary Studies in China) Beyond Boundaries - Women, Writing, and Visuality in Contemporary ChinaLet VeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Soul That Knows How To Sing - A Post - Structural Analysis of Kamala Das's Poetry - Swetha Antony - AcademiaDokument12 SeitenThe Soul That Knows How To Sing - A Post - Structural Analysis of Kamala Das's Poetry - Swetha Antony - Academiavarsham2Noch keine Bewertungen

- The EssayDokument2 SeitenThe EssayValentin ClaudiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lady LazarusDokument4 SeitenLady LazarusIonut D. Damian100% (2)

- Full Text 01Dokument30 SeitenFull Text 01Compte Pour TravaillerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper 05 Module 31 E TextDokument20 SeitenPaper 05 Module 31 E TextSubhra SantraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Mental Context of PoetryDokument23 SeitenThe Mental Context of PoetrykoprivikusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Knjiz 2 ParcijalaDokument19 SeitenKnjiz 2 ParcijalaEminaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing in No Man's Land - Questions of Gender and TranslationDokument11 SeitenWriting in No Man's Land - Questions of Gender and TranslationAlexandre MarcelinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Postmodernism: An Analysis of Elements of Postmodernist Literature in A. K. Ramanujan's Selected PoemsDokument4 SeitenIntroduction To Postmodernism: An Analysis of Elements of Postmodernist Literature in A. K. Ramanujan's Selected PoemsHamzahNoch keine Bewertungen

- And: A Portrait of The Artist As A Young Woman: The WriterDokument7 SeitenAnd: A Portrait of The Artist As A Young Woman: The WriterAnna Beatryz R. CardosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Changes of Heart: A Study of the Poetry of W. H. AudenVon EverandChanges of Heart: A Study of the Poetry of W. H. AudenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feminist DiscourseDokument15 SeitenFeminist DiscoursevirtualrushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bodies and Self-DisclosureDokument24 SeitenBodies and Self-DisclosureSilvia DMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approaches To Literary CriticismDokument24 SeitenApproaches To Literary CriticismCres Jules ArdoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ronald Bogue: "Deleuze's Style"Dokument18 SeitenRonald Bogue: "Deleuze's Style"pastorisilliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Penelopiad Exam Notes:EssayDokument3 SeitenThe Penelopiad Exam Notes:Essaygajan0% (1)

- 04-06-2021-1622788485-6-Impact - Ijrhal-4. Ijrhal - The Scarlet Letter Is Not A Puritan Novel But A Novel About The PuritansDokument4 Seiten04-06-2021-1622788485-6-Impact - Ijrhal-4. Ijrhal - The Scarlet Letter Is Not A Puritan Novel But A Novel About The PuritansImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAPTER 1 SYNTHESIS (The Maternal Disinheritance)Dokument5 SeitenCHAPTER 1 SYNTHESIS (The Maternal Disinheritance)KC TenorioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reinforcing Ideologies About Women: A Critique of The English Texts For UndergraduatesDokument9 SeitenReinforcing Ideologies About Women: A Critique of The English Texts For Undergraduatesnasem03218809980Noch keine Bewertungen

- Poaching On Men's Philosophies of RhetoricDokument17 SeitenPoaching On Men's Philosophies of RhetoricMarcosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Miguk and AmericaDokument17 SeitenMiguk and AmericaYoungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Masculinity, Whiteness, and The New EconomyDokument11 SeitenMasculinity, Whiteness, and The New EconomyFUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barony of Royston SecurityDokument4 SeitenBarony of Royston SecurityPAUL KAY FOSTER MACKENZIENoch keine Bewertungen

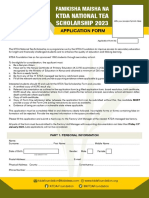

- KTDA Foundation 2023 Application Form 1 1Dokument5 SeitenKTDA Foundation 2023 Application Form 1 1johnny muhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Castillo vs. CastilloDokument7 SeitenCastillo vs. CastilloRomy IanNoch keine Bewertungen

- What's The Safe Period - New Health AdvisorDokument3 SeitenWhat's The Safe Period - New Health AdvisorEpatrick SisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Possessive CaseDokument9 SeitenPossessive CaseKevin LOZANO RAMIREZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family: Characteristics of A Healthy FamilyDokument14 SeitenFamily: Characteristics of A Healthy FamilyRoyce Vincent TizonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Children and Youth Services Review: Sonya Negriff TDokument8 SeitenChildren and Youth Services Review: Sonya Negriff TCrisstina AndreeaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017-11-30 Tier 2 5 Register of SponsorsDokument1.911 Seiten2017-11-30 Tier 2 5 Register of SponsorsjeffreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- TMS - Feminism and The Future of Women (Guidebook) PDFDokument74 SeitenTMS - Feminism and The Future of Women (Guidebook) PDFMohammad IrfanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reviewer Phil LitDokument7 SeitenReviewer Phil LitGirlieAnnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Checklist of Requirements For Municipal MeetDokument1 SeiteChecklist of Requirements For Municipal MeetKhrizzle Agsalon-VinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Genogram Assignment Mathews MarkDokument5 SeitenGenogram Assignment Mathews Markapi-664106052Noch keine Bewertungen

- Borang HC Tahun 6Dokument54 SeitenBorang HC Tahun 6ju9dahNoch keine Bewertungen

- William Wordsworth: William Wordsworth (1770-1850), British Poet, Credited With Ushering in The EnglishDokument2 SeitenWilliam Wordsworth: William Wordsworth (1770-1850), British Poet, Credited With Ushering in The EnglishMINoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment in Civil Law Review IDokument10 SeitenAssignment in Civil Law Review IMiguel Anas Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen