Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Climate Change and Health Fact Sheet

Hochgeladen von

Nuraimi NadirahOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Climate Change and Health Fact Sheet

Hochgeladen von

Nuraimi NadirahCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Climate Change and Health

Human-caused climate changes lead to the deaths of at least 150,000 people around the world every year,1 a figure which

is likely to increase as global warming continues to exacerbate existing environmental health threats around the world.

Children, the elderly, and those in disadvantaged communities are the most vulnerable to such exacerbations. The

following expected health impacts of global climate change can be separated into direct and indirect effects. Direct

impacts stem from extreme events such as heatwaves, floods, droughts, windstorms, and wildfires, while the indirect

effects may arise from the disruption of natural systems, causing infectious disease, malnutrition, food and water-borne

illness, and increased air pollution.

Heatwaves and UV Radiation

Heat already accounts for the greatest number of

weather-related deaths in the United States. There has

been a 50% increase in the number of unusually warm

nights, which deprives the body of breaks from the heat.2

The elderly and young children are most susceptible to

the effects of heat stress. Most heat related deaths occur

in cities, where what is known as the urban heat island

effect can potentially amplify temperatures as much as

10 C. Low-income families are especially vulnerable to

heat because they may have less access to adaptive

features such as thorough insulation or air-conditioning.3

The stratospheric ozone layer absorbs most of the

harmful UV radiation emitted from the sun, but that

amount of absorption has decreased since ozonedepleting substances, which are also powerful

greenhouse gases, caused the thinning of the ozone

layer. Children burn from sun exposure easily, putting

them at increased risk of skin damage from UV

radiation.4 A study showed that children sunburned

between the ages of 10 and 15 years have a threefold

increase in the risk of later developing skin cancer.5

Floods, Droughts, & Wildfires

Sea level rise is already putting low-lying coastal

populations at risk, and intense rainfall events are

projected to increase with climate change. This increases

the risk of flooding, which can introduce chemicals,

pesticides, and heavy metals into water systems and

increase the risk of water-borne disease outbreak.

Droughts, which are expected to become more common

in the United States, can destroy crops and grazing land,

reduce the quantity and quality of water resources, and

increase risk of fire. Furthermore, the increase in the

frequency and intensity of wildfires that has occurred

over the past few decades is very likely to continue. In

addition to destroying homes and property, these

wildfires can cause eye and respiratory diseases. Strong

tropical storms, like Hurricane Katrina in 2005, are also

likely to become more common with climate change,2 the

trauma of which can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder,

grief, depression, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders,

and drug and alcohol abuse.6

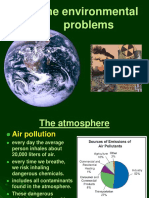

Air Pollution and Aeroallergens

Climate change is projected to cause more respiratory

disease. Higher temperatures cause ground-level ozone to

increase, and short term exposure to ozone increases the

rate and severity of asthma attacks, causes nasal and eye

irritation, coughs, bronchitis, and respiratory infections. In

addition, long-term exposure may lead to the development

of asthma. Children are more vulnerable to these effects

because they take in more air per body weight than adults

and have narrower airways. The severity of asthma is also

affected by aeroallergens, concentrations of which are

projected to increase with increasing temperature. For

example, ragweed is a particularly important risk to

human health: it has highly allergic pollen and is

spreading in several parts of the world.7 Allergic reactions

to poison ivy may also increase because these plants grow

faster and become more potent when carbon dioxide levels

are higher. Furthermore, algal blooms, which may cause

respiratory irritation, are increasing on a global scale.8

Vector-borne Disease

Climate change may cause vector-borne diseases to shift

in geographic distribution as well as changes in vector

development, reproduction, behavior, and population

dynamics.

Malaria: By 2080, an estimated 260-320 million

more people around the world will be affected by

malaria as a result of climate change.9 Children are

most at risk: 75% of malaria deaths occur in children

under five.10

Dengue fever/DHS: Children aged three to five have

a greater risk of developing dengue hemorrhagic

fever, which has a death rate of 50%. By 2080, about

2.5 billion more people will be at risk of contracting

dengue fever globally. The disease has shifted north

and has already reached the borderlands of Mexico

and the United States.11

West Nile Virus, Rift Valley fever, and

Chikungunya fever have also demonstrated shifts

related to higher temperatures and increased

precipitation from climate change.

Tick-borne Disease: Cases of Lyme disease have

increased from less than 100 cases per year in 2000

to more than 500 in 2007, and may continue to

expand its reach northward.12 Ticks carrying

encephalitis and Rocky Mountain spotted fever are

also projected to shift from south to north as

temperatures rise.13

Hantavirus: Weather extremes increase the risk of

hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, which is

transmitted by rodents.14

Food and Water-borne Disease

Outbreaks of infectious diarrhea, Cryptosporidium,

Giardia, Salmonella, E. coli, and rotavirus are projected

to increase. These diseases occur as a result of the

contamination of water supplies through the disruption

of water and sanitation systems, which can be caused by

toxic runoff from increased rainfall and flooding. Food

contamination can result from lack of air-conditioning or

refrigeration; for example, higher temperatures in

Europe were found to contribute to an estimated increase

of 30% in cases of Salmonella.15,16 Children are

especially vulnerable to food and water borne-diseases

because they are more likely to die from dehydration

from diarrhea and vomiting. Minority children and

children of lower socioeconomic status in areas that lack

adequate capacity to provide food and water supplies are

at the greatest risk.

Malnutrition and Resource Scarcity

Globally, approximately 800 million people are

currently undernourished. Climate change is likely to

further affect food production, distribution, and storage,

especially in sub-Saharan Africa. In the United States,

higher food prices are more likely to lead to foodinsecurity than an actual shortage. In 2005 there were a

reported 35 million food-insecure people in the United

States, 12.4 million of them children, mostly of AfricanAmerican or Hispanic descent.17 Water availability is

also projected to decrease with climate change.

According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment of

2005, 60% of global resources are already in decline or

are being used in unsustainable ways.18 Resource

scarcity coupled with population growth can lead to war,

political instability, poverty, substance abuse, crop or

catch failure, rising consumer prices, and the disruption

of social structure.

1. Anthony J. McMichael et al. in Comparative Quantification of

Health Risks: Global and Regional Burden of Disease due to Selected

Major Risk Factors, ed. Ezzati, M. Lopez, A.D. Rodgers, A & Murray,

C.J.L., 1543-1649 (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004).

2. National Science and Technology Council, Scientific Assessment of

the Effects of Global Change on the United States (Washington D.C.:

Committee on Environment and Natural Resources, 2008).

3. J. Andrew Hoerner and Nia Robinson, A Climate of Change

(Oakland: The Environmental Justice and Climate Change Initiative,

2008), 11.

4. Katherine M. Shea, Global Climate Change and Children's Health,

Pediatrics 120 (2007): e1359.

5. American Cancer Society, Skin Cancer Fact Sheet (Atlanta, Ga:

American Cancer Society; 1996).

6. Janet Swim et al., Psychology and Global Climate Change:

Addressing a Multi-faceted Phenomenon and Set of Challenges

(American Psychological Association, 2009).

7. International Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2007:

Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group

II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change, eds. M.L. Parry et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2007).

8. Stephanie K. Moore et al., Impacts of climate variability and future

climate change on harmful algal blooms and human health,

Environmental Health 7 (2008): S4.

9. Anthony Costello et al., Managing the health effects of climate

change, The Lancet 373 (2009): 1702.

10. P. Krause, Malaria (Plasmodium), in: Nelson Textbook of

Pediatrics, 16th edition, edited by RE Berhman et al. (Philadelphila,

PA: WB Saunders Co, 2000).

11. World Health Organization, Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic

fever. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en//.

12. Maine CDC, Lyme Disease Surveillance Report Maine 2008,

http://www.maine.gov/dhhs/boh/ddc/epi/publications/2008-Lymedisease-Surveillance-Report.pdf.

13. Supinda Bunyavanich et al., The Impact of Climate Change on

Child Health, Ambulatory Pediatrics 3 (2003): 44-52.

14. Center for Health and the Global Environment, Climate Change

and Health in New Mexico, Harvard Medical School 2009.

15. Jonathan A. Patz, Impact of regional climate change on human

health, Nature 438 (2005): 310-317.

16. R.S. Kovats et al., The effect of temperature on food poisoning: a

time-series analysis of salmonellosis in ten European countries,

Epidemiology and Infection 132 (2004): 443-453.

17. David Wood, Effect of Child and Family Poverty on Child Health

in the United States, Pediatrics 112 (2003): 707-711.

18. Paul R. Epstein, Climate change and Human Health, New

England Journal of Preventative Medicine 353 (2005): 1433-1436.

4301 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 160 Washington, DC

20008 202.833.2933 Email: health@neefusa.org

www.neefusa.org/health.htm

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Climate Change Fact Sheet Brand UpdateDokument3 SeitenClimate Change Fact Sheet Brand UpdateRonald AlvaradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects Solid Waste Treatment and DisposalDokument5 SeitenEffects Solid Waste Treatment and DisposalNdahayoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change: Human Rights 1ADokument15 SeitenClimate Change: Human Rights 1AAlan GultiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Effects On HealthDokument26 SeitenClimate Effects On HealthLean Ashly MacarubboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change and Health in JamaicaDokument2 SeitenClimate Change and Health in JamaicaGail HoadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Health As A Motivator For Climate Change Adaptation and MitigationDokument5 SeitenHuman Health As A Motivator For Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigationapi-272488699Noch keine Bewertungen

- Articles On National IssuesDokument116 SeitenArticles On National IssuesdukkasrinivasflexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Long Truong-1500w.editedDokument7 SeitenLong Truong-1500w.editedJessy NgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Global Warming On Our HealthDokument3 SeitenEffects of Global Warming On Our HealthRifat Rahman SiumNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Climate Change?: Assessment Report Concludes That Climate Change Has Probably Already BegunDokument9 SeitenWhat Is Climate Change?: Assessment Report Concludes That Climate Change Has Probably Already BegunjafcachoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming and Excessive Climate Change A Risk To Human Lives.Dokument6 SeitenGlobal Warming and Excessive Climate Change A Risk To Human Lives.wamburamuturi001Noch keine Bewertungen

- Missing Microbes: How the Overuse of Antibiotics Is Fueling Our Modern PlaguesVon EverandMissing Microbes: How the Overuse of Antibiotics Is Fueling Our Modern PlaguesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- ClimateHealth RMITDokument12 SeitenClimateHealth RMITodetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Climate Change To HumanDokument10 SeitenEffects of Climate Change To HumanJan Vincent Valencia RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Protect Yourself: Advice For The Public Myth Busters Questions and Answers Situation Reports All Information On The COVID-19 OutbreakDokument56 SeitenProtect Yourself: Advice For The Public Myth Busters Questions and Answers Situation Reports All Information On The COVID-19 OutbreakJennylyn GuadalupeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Enviromental Health ProblemDokument36 SeitenGlobal Enviromental Health Problemsufian abdo jiloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Occupational and Environmental Health Assignment: Masters in Public Health (MPH)Dokument10 SeitenOccupational and Environmental Health Assignment: Masters in Public Health (MPH)Nadrah HaziziNoch keine Bewertungen

- The blood bath has begun, are we too late to save humanity?Von EverandThe blood bath has begun, are we too late to save humanity?Noch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change & Waterborne Disease Climate Change & Waterborne DiseaseDokument16 SeitenClimate Change & Waterborne Disease Climate Change & Waterborne DiseasetanishaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change HealthDokument2 SeitenClimate Change HealthNur SolichahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change Induced Environmental Health of Children - PaperDokument33 SeitenClimate Change Induced Environmental Health of Children - PaperADB Poverty ReductionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Key Facts - 20240204 - 205908 - 0000Dokument3 SeitenKey Facts - 20240204 - 205908 - 0000jovelcastro329Noch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Problems Due To Global Warming and Climate Change Global and Bangladesh PerspectivesDokument11 SeitenEnvironmental Problems Due To Global Warming and Climate Change Global and Bangladesh PerspectivesrahilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change PaperDokument13 SeitenClimate Change Paperapi-531666073Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ass Triangle of Human EcologyDokument6 SeitenAss Triangle of Human EcologyClarissa Marie Limmang100% (1)

- Climate Change and Impact On HealthsDokument8 SeitenClimate Change and Impact On HealthsNakul RaibahadurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Audrey Kubis-Discourseproject 2Dokument8 SeitenAudrey Kubis-Discourseproject 2api-579157817Noch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change and Public Health: Nautilus Institute at RMITDokument2 SeitenClimate Change and Public Health: Nautilus Institute at RMITAttamam TamamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Social and Political Consequences of Abrupt Climate ChangeDokument13 SeitenThe Social and Political Consequences of Abrupt Climate Changeapi-533471367Noch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change On HumanDokument5 SeitenClimate Change On HumanSisa RuwanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bridge EssayDokument5 SeitenBridge Essayoliveck10Noch keine Bewertungen

- Enviromedics by Jay Lemery and Paul Auerbach Is A Book About The Impact of ClimateDokument4 SeitenEnviromedics by Jay Lemery and Paul Auerbach Is A Book About The Impact of ClimateAnsh SrivastavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CPH PrefinalDokument22 SeitenCPH PrefinalZharmaine ChavezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tsunami in South Asia: What Is The Risk of Post-Disaster Infectious Disease Outbreaks?Dokument7 SeitenTsunami in South Asia: What Is The Risk of Post-Disaster Infectious Disease Outbreaks?Andha HandayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- INTRODUCTIONDokument14 SeitenINTRODUCTIONmoses samuelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Policy Memo: Climate Change and SecurityDokument11 SeitenPolicy Memo: Climate Change and SecurityJuan ForrerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environment and HealthDokument2 SeitenEnvironment and HealthSajjal NoorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obesity and Lung Disease: A Guide to ManagementVon EverandObesity and Lung Disease: A Guide to ManagementAnne E. DixonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate ChangeDokument82 SeitenClimate ChangeSimer FibersNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Environmental ProblemsDokument19 SeitenThe Environmental ProblemsAlexandru GribinceaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change Is A Pressing Issue That Has Significant and Far-Reaching Ef - 20240204 - 202428 - 0000Dokument6 SeitenClimate Change Is A Pressing Issue That Has Significant and Far-Reaching Ef - 20240204 - 202428 - 0000jovelcastro329Noch keine Bewertungen

- Global Environmental Change and Infectious DiseaseDokument2 SeitenGlobal Environmental Change and Infectious Diseasejhean dabatosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Health Impacts & AdaptationDokument10 SeitenHuman Health Impacts & AdaptationSaleh UsmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Children's Vulnerability To Environmental Health An OverviewDokument4 SeitenChildren's Vulnerability To Environmental Health An OverviewKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNoch keine Bewertungen

- W9L1 - Article CDokument2 SeitenW9L1 - Article CShaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming: The Biggest Threat of The Century 1Dokument8 SeitenGlobal Warming: The Biggest Threat of The Century 1Nour El Houda ChaibiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Department of Life Sciences: So What Is Climate Change?Dokument5 SeitenDepartment of Life Sciences: So What Is Climate Change?lekha1997Noch keine Bewertungen

- Module 9 Project - Environmental HealthDokument3 SeitenModule 9 Project - Environmental HealthAdeola JosephNoch keine Bewertungen

- ReportDokument12 SeitenReportJeane ann JordanNoch keine Bewertungen

- FS - ParmaClosure Environmental ArticleDokument3 SeitenFS - ParmaClosure Environmental ArticleLaramy Lacy MontgomeryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Global Warming: HumanDokument2 SeitenEffects of Global Warming: HumanJoyce Nichole SuarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pandemic Effect: Ninety Experts on Immunizing the Built EnvironmentVon EverandThe Pandemic Effect: Ninety Experts on Immunizing the Built EnvironmentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Know Something Concerning Climate Change Go Through This For Details!.20140512.154710Dokument2 SeitenKnow Something Concerning Climate Change Go Through This For Details!.20140512.154710cannonash16Noch keine Bewertungen

- Essay On Climate Change PDFDokument11 SeitenEssay On Climate Change PDFNida ChaudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effect of Climate Change On HumansDokument2 SeitenThe Effect of Climate Change On HumansVijaaynranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jenny Spyres: Increasing Threat From The EnvironmentDokument5 SeitenJenny Spyres: Increasing Threat From The EnvironmentkimoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- TLE - Waste ManagementDokument22 SeitenTLE - Waste ManagementRobe SolonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iaea Tecdoc 1472 PDFDokument584 SeitenIaea Tecdoc 1472 PDFRussell ClarkNoch keine Bewertungen

- VSEPR (Shapes of Molecules) and Photochemical Smog RevisionDokument3 SeitenVSEPR (Shapes of Molecules) and Photochemical Smog RevisionAnonymous X8U3fpNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Air Quality ModelingDokument27 SeitenAir Quality ModelingZara IqbalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2010-01-1272 Catalyst Aging Method For Future Emissions Standard RequirementsDokument19 Seiten2010-01-1272 Catalyst Aging Method For Future Emissions Standard RequirementsSaurabh SumanNoch keine Bewertungen

- ORP Versus AmperometryDokument7 SeitenORP Versus AmperometryRoman MangalindanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hazardous Waste Case - Minamata Disease-Mercury Poisoning - 1950s-60sDokument13 SeitenHazardous Waste Case - Minamata Disease-Mercury Poisoning - 1950s-60sOPGJrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidro FrackingDokument24 SeitenHidro FrackingCalitoo IGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jehovah's Witnesses Warwick Property ContaminationDokument11 SeitenJehovah's Witnesses Warwick Property ContaminationsirjsslutNoch keine Bewertungen

- Errors Test - 1 (Questions From Previous Banking Exams)Dokument2 SeitenErrors Test - 1 (Questions From Previous Banking Exams)nilesh dhamaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Field (11 y 12) PDFDokument43 SeitenField (11 y 12) PDFGabriela ÑañezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Register Evaluation of Possible Emergencies (FMEA)Dokument4 SeitenEnvironmental Register Evaluation of Possible Emergencies (FMEA)Pandu BirumakovelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 FlotationDokument27 Seiten4 FlotationAnonymous c8tyA5XlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uv Disinfection Systems Tak SeriesDokument12 SeitenUv Disinfection Systems Tak SeriesCarlos RamírezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 MirandaDokument93 Seiten2013 MirandaRazif YusufNoch keine Bewertungen

- Khush BakhtDokument26 SeitenKhush BakhtMuhammad YousafNoch keine Bewertungen

- KSCST PresentationDokument44 SeitenKSCST PresentationAkshay SavvasheriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis BDokument312 SeitenAnalysis BKaren Sallo100% (1)

- Documents For Design and Construction of SVE/BV Systems: 6-1. IntroductionDokument6 SeitenDocuments For Design and Construction of SVE/BV Systems: 6-1. IntroductionAndré OliveiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Product Safety Assessment EthyleneDokument7 SeitenProduct Safety Assessment EthyleneBamrung SungnoenNoch keine Bewertungen

- EC - Case - Number - 86 - Bird Airport Hotel Pvt. Ltd. Dated 06.06Dokument6 SeitenEC - Case - Number - 86 - Bird Airport Hotel Pvt. Ltd. Dated 06.06nairfurnitureNoch keine Bewertungen

- Msds Irganox L 135Dokument7 SeitenMsds Irganox L 135budi budihardjoNoch keine Bewertungen

- WATER ACT, 1974: (Prevention and Control of Pollution)Dokument15 SeitenWATER ACT, 1974: (Prevention and Control of Pollution)ritik sarkarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fueling Station DesignDokument8 SeitenFueling Station Designlchavez04Noch keine Bewertungen

- Booth Application For Independence FestivalDokument2 SeitenBooth Application For Independence FestivalSCGC_ChamberNoch keine Bewertungen

- IM T20 - T60 TX001 B01 EN - TransDokument12 SeitenIM T20 - T60 TX001 B01 EN - TransGunnar HaffkeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2021 Esm 410 Topic Environmental ManagementDokument11 Seiten2021 Esm 410 Topic Environmental ManagementEdwardsNoch keine Bewertungen

- UK Fuel Storage Regulations - Sterling Fuel LTDDokument4 SeitenUK Fuel Storage Regulations - Sterling Fuel LTDMylesSterlingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jharkhand State Pollution Control Board, Ranchi: 7. Bank DetailsDokument6 SeitenJharkhand State Pollution Control Board, Ranchi: 7. Bank DetailsanjaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- 00final F-35 Fde Ws EisDokument578 Seiten00final F-35 Fde Ws Eisamenendezam100% (1)