Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Chapter 7 Consti Digests

Hochgeladen von

Lady BancudCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Chapter 7 Consti Digests

Hochgeladen von

Lady BancudCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Chapter

7 Case Digests

Garcia vs. Executive Secretary

211 SCRA 219 Political Law Congress Authorizing the President to Tax

In November 1990, President Corazon Aquino issued Executive Order No.

438 which imposed, in addition to any other duties, taxes and charges

imposed by law on all articles imported into the Philippines, an additional

duty of 5% ad valorem tax. This additional duty was imposed across the

board on all imported articles, including crude oil and other oil products

imported into the Philippines. In 1991, EO 443 increased the additional duty

to 9%. In the same year, EO 475 was passed reinstating the previous 5%

duty except that crude oil and other oil products continued to be taxed at

9%. Enrique Garcia, a representative from Bataan, avers that EO 475 and

478 are unconstitutional for they violate Section 24 of Article VI of the

Constitution which provides:

All appropriation, revenue or tariff bills, bills authorizing increase of the

public debt, bills of local application, and private bills shall originate

exclusively in the House of Representatives, but the Senate may propose or

concur with amendments.

He contends that since the Constitution vests the authority to enact revenue

bills in Congress, the President may not assume such power by issuing

Executive Orders Nos. 475 and 478 which are in the nature of revenuegenerating measures.

ISSUE: Whether or not EO 475 and 478 are constitutional.

imposts . . . . In this case, it is the Tariff and Customs Code which

authorized the President ot issue the said EOs.

US vs. Ang Tang Ho

43 Phil. 1 Political Law Delegation of Power Administrative Bodies

In July 1919, the Philippine Legislature (during special session) passed and

approved Act No. 2868 entitled An Act Penalizing the Monopoly and Hoarding

of Rice, Palay and Corn. The said act, under extraordinary circumstances,

authorizes the Governor General (GG) to issue the necessary Rules and

Regulations in regulating the distribution of such products. Pursuant to this

Act, in August 1919, the GG issued Executive Order No. 53 which was

published on August 20, 1919. The said EO fixed the price at which rice

should be sold. On the other hand, Ang Tang Ho, a rice dealer, sold a ganta

of rice to Pedro Trinidad at the price of eighty centavos. The said amount

was way higher than that prescribed by the EO. The sale was done on the

6th of August 1919. On August 8, 1919, he was charged for violation of the

said EO. He was found guilty as charged and was sentenced to 5 months

imprisonment plus a P500.00 fine. He appealed the sentence countering that

there is an undue delegation of power to the Governor General.

HELD: Under Section 24, Article VI of the Constitution, the enactment of

appropriation, revenue and tariff bills, like all other bills is, of course, within

the province of the Legislative rather than the Executive Department. It does

not follow, however, that therefore Executive Orders Nos. 475 and 478,

assuming they may be characterized as revenue measures, are prohibited to

be exercised by the President, that they must be enacted instead by the

Congress of the Philippines.

ISSUE: Whether or not there is undue delegation to the Governor General.

Section 28(2) of Article VI of the Constitution provides as follows:

Anent the issue of undue delegation, the said Act wholly fails to provide

definitely and clearly what the standard policy should contain, so that it could

be put in use as a uniform policy required to take the place of all others

without the determination of the insurance commissioner in respect to

matters involving the exercise of a legislative discretion that could not be

delegated, and without which the act could not possibly be put in use. The

law must be complete in all its terms and provisions when it leaves the

legislative branch of the government and nothing must be left to the

judgment of the electors or other appointee or delegate of the legislature, so

that, in form and substance, it is a law in all its details in presenti, but

(2) The Congress may, by law, authorize the President to fix within specified

limits, and subject to such limitations and restrictions as it may impose, tariff

rates, import and export quotas, tonnage and wharfage dues, and other

duties or imposts within the framework of the national development program

of the Government.

There is thus explicit constitutional permission to Congress to authorize the

President subject to such limitations and restrictions as [Congress] may

impose to fix within specific limits tariff rates . . . and other duties or

HELD: First of, Ang Tang Hos conviction must be reversed because he

committed the act prior to the publication of the EO. Hence, he cannot be ex

post facto charged of the crime. Further, one cannot be convicted of a

violation of a law or of an order issued pursuant to the law when both the

law and the order fail to set up an ascertainable standard of guilt.

Chapter 7 Case Digests

which may be left to take effect in future, if necessary, upon the

ascertainment of any prescribed fact or event.

-

-

THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS and the HONG KONG &

SHANGHAI BANKING CORPORATION (HSBC) v. JOSE VERA, Judge ad

interim of the Court of First Instance of Manila, and MARIANO CU

UNJIENG (65 Phil 56)

November 16, 1937

FACTS:

-

The criminal case, People v. Cu Unjieng was filed in the Court of

First Instance (CFI) in Manila, with HSBC intervening in the case as

private prosecutor.

-

The CFI rendered a judgment of conviction sentencing Cu Unjieng to

an indeterminate penalty ranging from four years and two months

of prision correccional to eight years of prison mayor. (Jan. 8, 1934)

-

Upon appeal, it was modified to an indeterminate penalty of from

five years and six months of prison correccional to seven years, six

months and twenty-seven days of prison mayor, but affirmed the

judgments in all other respects.

-

Cu Unjieng filed a Motion for Reconsideration and four successive

motions for new trial which were all denied on December 17, 1935.

Final judgment was entered on Dec. 18, 1935. He filed for certiorari

to the Supreme Court but got denied on Nov 1936. The SC

subsequently denied Cu Unjiengs petition for leave to file a second

alternative motion for reconsideration or new trial, then remanded

the case to the court of origin for execution of judgment.

-

Cu Unjieng filed an application for probation before the trial court,

under the provisions of Act 4221 of the defunct Philippine

Legislature. He states he is innocent of the crime; he has no

criminal record; and that he would observe good conduct in the

future.

-

CFI Manila Judge Jose Vera set the petition for hearing for probation

on April 5, 1937.

-

HSBC questioned the authority of Vera to hold such hearings and

assailed the constitutionality of the Probation Act since it violates

the equal protection of laws and gives unlawful and improper

delegation to provincial boards.

Section 11 of Art 4221 states that the act shall only be applied in

those provinces wherein the probationary officer is granted salary

not lower than provincial fiscals by respective provincial boards.

The City Fiscal of Manila files a supplementary petition affirming

issues raised by HSBC, arguing that probation is a form of reprieve,

hence Act 4221 bypasses this exclusive power of the Chief

Executive.

Hence this petition in the Supreme Court.

ISSUES:

1. Whether or not the constitutionality of Act 4221 has been properly

raised in these proceedings;

2. If in the affirmative, whether or not Act 4221 is constitutional based

on these three grounds:

a. It encroaches upon the pardoning power of the executive

b. It constitutes an undue delegation of legislative power

c. It denies the equal protection of the laws

HELD/RATIO:

1. Yes. Constitutional questions will not be determined by the courts

unless properly raised and presented in appropriate cases and is

necessary to a determination of the case, lis mota. Constitutionality

issues may be raised in prohibition and certiorari proceedings, as

they may also be raised in mandamus, quo warranto, and habeas

corpus proceedings. The general rule states that constitutionality

should be raised in the earliest possible opportunity (during

proceedings in initial/inferior courts). It may be said that the state

can challenge the validity of its own laws, as in this case. The wellsettled rule is that the person impugning validity must have

personal and substantial interest in the case (i.e. he has sustained,

or will sustain direct injury as a result of its enforcement). If Act

4221 is unconstitutional, the People of the Philippines have

substantial interest in having it set aside.

2.

a.

b.

No. There exists a distinction between pardon and

probation. Pardoning power is solely within the power of

the Executive. Probation has an effect of temporary

suspension, and the probationer is still not exempt from

the entire punishment which the law inflicts upon him as he

remains to be in legal custody for the time being.

Yes. The Probation Act does not lay down any definite

standards by which the administrative boards may be

Chapter 7 Case Digests

c.

guided in the exercise of discretionary powers, hence they

have the power to determine for themselves, whether or

not to apply the law or not. This therefore becomes a

surrender of legislative power to the provincial boards. It is

unconstitutional.

Yes. Due to the unwarranted delegation of legislative

power, some provinces may choose to adopt the law or

not, thus denying the equal protection of laws. It is

unconstitutional.

People vs. Vera

G.R. No. L-45685 November 16 1937 En Banc [Non Delegation of Legislative

Powers]

FACTS:

Cu-Unjieng was convicted of criminal charges by the trial court of Manila. He

filed a motion for reconsideration and four motions for new trial but all were

denied. He then elevated to the Supreme Court of United States for review,

which was also denied. The SC denied the petition subsequently filed by CuUnjieng for a motion for new trial and thereafter remanded the case to the

court of origin for execution of the judgment. CFI of Manila referred the

application for probation of the Insular Probation Office which recommended

denial of the same. Later, 7th branch of CFI Manila set the petition for

hearing. The Fiscal filed an opposition to the granting of probation to Cu

Unjieng, alleging, among other things, that Act No. 4221, assuming that it

has not been repealed by section 2 of Article XV of the Constitution, is

nevertheless violative of section 1, subsection (1), Article III of the

Constitution guaranteeing equal protection of the laws. The private

prosecution also filed a supplementary opposition, elaborating on the alleged

unconstitutionality on Act No. 4221, as an undue delegation of legislative

power to the provincial boards of several provinces (sec. 1, Art. VI,

Constitution).

The provincial boards of the various provinces are to determine for

themselves, whether the Probation Law shall apply to their provinces or not

at all. The applicability and application of the Probation Act are entirely

placed in the hands of the provincial boards. If the provincial board does not

wish to have the Act applied in its province, all that it has to do is to decline

to appropriate the needed amount for the salary of a probation officer.

The clear policy of the law, as may be gleaned from a careful examination of

the whole context, is to make the application of the system dependent

entirely upon the affirmative action of the different provincial boards through

appropriation of the salaries for probation officers at rates not lower than

those provided for provincial fiscals. Without such action on the part of the

various boards, no probation officers would be appointed by the Secretary of

Justice to act in the provinces. The Philippines is divided or subdivided into

provinces and it needs no argument to show that if not one of the provinces

and this is the actual situation now appropriate the necessary fund for

the salary of a probation officer, probation under Act No. 4221 would be

illusory. There can be no probation without a probation officer. Neither can

there be a probation officer without the probation system.

Araneta vs. Dinglasan

Facts:

Antonio Araneta is being charged for allegedly violating of Executive Order

62 which regulates rentals for houses and lots for residential buildings. Judge

Rafael Dinglasan was the judge hearing the case. Araneta appealed seeking

to prohibit Dinglasan and the Fiscal from proceeding with the case. He

averred that EO 62 was issued by virtue of Commonwealth Act (CA) No. 671

which he claimed ceased to exist, hence, the EO has no legal basis.

Three other cases were consolidated with this one. L-3055 which is an appeal

by Leon Ma. Guerrero, a shoe exporter, against EO 192 which controls

exports in the Philippines; he is seeking to have permit issued to him.

ISSUE:

Whether or not there is undue delegation of powers.

L-3054 is filed by Eulogio Rodriguez to prohibit the treasury from disbursing

funds [from 49-50] pursuant to EO 225.

RULING:

Yes. SC conclude that section 11 of Act No. 4221 constitutes an improper

and unlawful delegation of legislative authority to the provincial boards and

is, for this reason, unconstitutional and void.

The challenged section of Act No. 4221 in section 11 which reads as follows:

"This Act shall apply only in those provinces in which the respective

provincial boards have provided for the salary of a probation officer at rates

not lower than those now provided for provincial fiscals. Said probation

officer shall be appointed by the Secretary of Justice and shall be subject to

the direction of the Probation Office."

L-3056 filed by Antonio Barredo is attacking EO 226 which was appropriating

funds to hold the national elections.

They all aver that CA 671, otherwise known as AN ACT DECLARING A STATE

OF TOTAL EMERGENCY AS A RESULT OF WAR INVOLVING THE PHILIPPINES

AND AUTHORIZING THE PRESIDENT TO PROMULGATE RULES AND

REGULATIONS TO MEET SUCH EMERGENCY or simply the Emergency Powers

Act, is already inoperative and that all EOs issued pursuant to said CA had

likewise ceased.

Chapter 7 Case Digests

ISSUE: Whether or not CA 671 has ceased.

HELD: Yes. CA 671, which granted emergency powers to the president,

became inoperative ex proprio vigore when Congress met in regular session

on May 25, 1946, and that Executive Orders Nos. 62, 192, 225 and 226 were

issued without authority of law. In setting the first regular session of

Congress instead of the first special session which preceded it as the point of

expiration of the Act, the SC is giving effect to the purpose and intention of

the National Assembly. In a special session, the Congress may consider

general legislation or only such subjects as he (President) may designate.

Such acts were to be good only up to the corresponding dates of

adjournment of the following sessions of the Legislature, unless sooner

amended or repealed by the National Assembly. Even if war continues to

rage on, new legislation must be made and approved in order to continue the

EPAs, otherwise it is lifted upon reconvening or upon early repeal.

Araneta v Dinglasan

G.R. No. L-2044 August 26, 1949

Tuason, J.:

Facts:

1. The petitions challenged the validity of executive orders issued by virtue

of CA No. 671 or the Emergency Powers Act. CA 671 declared a state of

emergency as a result of war and authorized the President to promulgate

rules and regulations to meet such emergency. However, the Act did not fix

the duration of its effectivity.

2.

EO 62 regulates rentals for houses and lots for residential buildings.

The petitioner, Araneta, is under prosecution in the CFI for violation of the

provisions of this EO 62 and prays for the issuance of the writ of prohibition.

3.

EO 192, aims to control exports from the Philippines. Leon Ma.

Guerrero seeks a writ of mandamus to compel the Administrator of the Sugar

Quota Office and the Commissioner of Customs to permit the exportation of

shoes. Both officials refuse to issue the required export license on the ground

that the exportation of shoes from the Philippines is forbidden by this EO.

4.

EO 225, which appropriates funds for the operation of the

Government during the period from July 1, 1949 to June 30, 1950, and for

other purposes was assailed by petitioner Eulogio Rodriguez, Sr., as a taxpayer, elector, and president of the Nacionalista Party. He applied for a writ

of prohibition to restrain the Treasurer of the Philippines from disbursing the

funds by virtue of this EO.

5.

Finally, EO 226, which appropriated P6M to defray the expenses in

connection with the national elections in 1949. was questioned by Antonio

Barredo, as a citizen, tax-payer and voter. He asked the Court to prevent

"the respondents from disbursing, spending or otherwise disposing of that

amount or any part of it."

ISSUE: Whether or not CA 671 ceased to have any force and effect

YES.

1. The Act fixed a definite limited period. The Court held that it became

inoperative when Congress met during the opening of the regular

session on May 1946 and that EOs 62, 192, 225 and 226 were

issued without authority of law . The session of the Congress is the

point of expiration of the Act and not the first special session after

it.

Executive Orders No. 62 (dated June 21, 1947) regulating house and lot

rentals, No. 192 (dated December 24, 1948) regulating exports, Nos. 225

and 226 (dated June 15,1949) the first appropriation funds for the operation

of the Government from July 1, 1949 to June 30, 1950, and the second

appropriating funds for election expenses in November 1949, were therefore

declared null and void for having been issued after Act No. 671 had lapsed

and/or after the Congress had enacted legislation on the same subjects. This

is based on the language of Act 671 that the National Assembly restricted

the life of the emergency powers of the President to the time the Legislature

was prevented from holding sessions due to enemy action or other causes

brought on by the war.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Can You Find The Names of 25 Books of The Bible in This ParagraphDokument1 SeiteCan You Find The Names of 25 Books of The Bible in This ParagraphLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

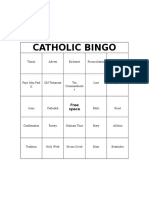

- Catholic Bingo: Trinity Advent Eucharist Reconciliation ApostlesDokument7 SeitenCatholic Bingo: Trinity Advent Eucharist Reconciliation ApostlesLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- CitizenshipDokument37 SeitenCitizenshipLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- The in Pari Delicto RuleDokument1 SeiteThe in Pari Delicto RuleLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Requirements of Contract ModificationDokument3 SeitenLegal Requirements of Contract ModificationLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- 224 SCRA 437 - Intellectual Property Law - Law On TrademarksDokument8 Seiten224 SCRA 437 - Intellectual Property Law - Law On TrademarksLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pearl & Dean (Phil.), Inc. v. Shoemart, Inc. and North Edsa Marketing, Inc. G.R. No. 148222, August 15, 2003 Corona, J. FactsDokument4 SeitenPearl & Dean (Phil.), Inc. v. Shoemart, Inc. and North Edsa Marketing, Inc. G.R. No. 148222, August 15, 2003 Corona, J. FactsLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- TORRES VsDokument1 SeiteTORRES VsLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dermaline, Inc. vs. Myra Pharmaceuticals, Inc., GR No. 190065, August 16, 2010Dokument6 SeitenDermaline, Inc. vs. Myra Pharmaceuticals, Inc., GR No. 190065, August 16, 2010Lady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consolidated IPL (PG 10-18)Dokument23 SeitenConsolidated IPL (PG 10-18)Lady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Additional Cases DigestsDokument8 SeitenAdditional Cases DigestsLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- ContractsDokument1 SeiteContractsLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manlar vs. DeytoDokument2 SeitenManlar vs. DeytoLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disposition of Obligations Under Extraordinary InflationDokument2 SeitenDisposition of Obligations Under Extraordinary InflationLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cagayan Valley vs. CADokument1 SeiteCagayan Valley vs. CALady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cheryl 19-21Dokument6 SeitenCheryl 19-21Lady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disposition of Obligations Under Extraordinary InflationDokument2 SeitenDisposition of Obligations Under Extraordinary InflationLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamentals of Compensation in The Extinguishment of An ObligationDokument2 SeitenFundamentals of Compensation in The Extinguishment of An ObligationLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Batch 2 #S 59 and 60Dokument3 SeitenBatch 2 #S 59 and 60Wsrc SmrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Municipal Court Ruling on Contract Dispute and Writ of AttachmentDokument14 SeitenMunicipal Court Ruling on Contract Dispute and Writ of AttachmentLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- CEMBRANO VS. CITY OF BUTUAN - Payment to Wrong Party Does Not Extinguish ObligationDokument2 SeitenCEMBRANO VS. CITY OF BUTUAN - Payment to Wrong Party Does Not Extinguish ObligationLady Bancud100% (1)

- Obligations Nature and Effects of ObligationsDokument56 SeitenObligations Nature and Effects of ObligationsLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICERDDokument6 SeitenICERDLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unno Commercial Enterprises and Societe-2Dokument3 SeitenUnno Commercial Enterprises and Societe-2Lady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obli Statute of FraudsDokument11 SeitenObli Statute of FraudsLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bancud 49,50,51Dokument3 SeitenBancud 49,50,51Lady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- SAMSON V. CABANOS 2005Dokument3 SeitenSAMSON V. CABANOS 2005Lady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tet Dillera - #4-6 - Mirpuri To Philip MorrisDokument5 SeitenTet Dillera - #4-6 - Mirpuri To Philip MorrisLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lacoste vs. Fernandez: Unfair Competition in Trademark RegistrationDokument2 SeitenLacoste vs. Fernandez: Unfair Competition in Trademark RegistrationLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine trademark cases on similarity, goodwill and mootnessDokument3 SeitenPhilippine trademark cases on similarity, goodwill and mootnessLady BancudNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Dobritch, Alan Gregory (PD Intern)Dokument5 SeitenDobritch, Alan Gregory (PD Intern)James LindonNoch keine Bewertungen

- C. Bloomberry Resorts and Hotels Inc. vs. Bureau of Internal RevenueDokument2 SeitenC. Bloomberry Resorts and Hotels Inc. vs. Bureau of Internal RevenueJoieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wu V Carleton Condominium CorporationDokument7 SeitenWu V Carleton Condominium Corporationcondomadness13Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ridiculous Email Chain With Little Rock Police DepartmentDokument13 SeitenRidiculous Email Chain With Little Rock Police DepartmentRuss RacopNoch keine Bewertungen

- Probate Court Exceeds Jurisdiction in Determining Property TitleDokument2 SeitenProbate Court Exceeds Jurisdiction in Determining Property TitleKarez MartinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Analysis 6Dokument12 SeitenCase Analysis 6Nikhil KalyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admission Form PDFDokument3 SeitenAdmission Form PDFsrishtiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Purchased Goods - Cheque DishonourDokument2 SeitenPurchased Goods - Cheque DishonourNagarjunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Ethics and Judicial Ethics Case DigestsDokument2 SeitenLegal Ethics and Judicial Ethics Case DigestsChris Von0% (1)

- JG Summit Holdings vs. CADokument3 SeitenJG Summit Holdings vs. CAFrancis Kyle Cagalingan SubidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lyceum of the Philippines vs Court of Appeals ruling on use of "LyceumDokument2 SeitenLyceum of the Philippines vs Court of Appeals ruling on use of "LyceumjohnsalongaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engr. Gerardo P. CorsigaDokument2 SeitenEngr. Gerardo P. CorsigaTonton ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application For Ombudsman Clearance (Omb Form 1) : Republic of The Philippines Office of The OmbudsmanDokument1 SeiteApplication For Ombudsman Clearance (Omb Form 1) : Republic of The Philippines Office of The OmbudsmanMissEu Ferrer MontericzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organic Theory: HL Bolton (Engineering) Co LTD V TJ Graham & Sons LTDDokument3 SeitenOrganic Theory: HL Bolton (Engineering) Co LTD V TJ Graham & Sons LTDKhoo Chin KangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Balbir Singh CommentaryDokument5 SeitenBalbir Singh CommentaryArindam BharadwajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endicott Law Is Necesarilly VagueDokument8 SeitenEndicott Law Is Necesarilly VagueClari PollitzerNoch keine Bewertungen

- G. R. No. 108998 Republic Vs Court of Appeals Mario Lapina and Flor de VegaDokument5 SeitenG. R. No. 108998 Republic Vs Court of Appeals Mario Lapina and Flor de VegaNikko Franchello SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Invalid or Void Orders From JudgesDokument5 SeitenInvalid or Void Orders From JudgesFayyazHaneef33% (3)

- 2nd-Set CRIM Case-Digest 24-25 20190208Dokument2 Seiten2nd-Set CRIM Case-Digest 24-25 20190208Hemsley Battikin Gup-ayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amatuzio Etc. IndictedDokument3 SeitenAmatuzio Etc. Indictedjhansen815Noch keine Bewertungen

- Republic v. Manalo, G.R. No. 221029, April 24, 2018 (Art 26)Dokument15 SeitenRepublic v. Manalo, G.R. No. 221029, April 24, 2018 (Art 26)Kristelle IgnacioNoch keine Bewertungen

- CrimPro Jurisprudence DoctrineDokument24 SeitenCrimPro Jurisprudence DoctrineAbegail Protacio GuardianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chavez v. Public Estates Authority, 384 SCRA 152 (2000)Dokument2 SeitenChavez v. Public Estates Authority, 384 SCRA 152 (2000)Al Jay MejosNoch keine Bewertungen

- By Anandram Sankar GENERALLY, SEZ Entities Export Goods/services or Supply Goods/services To Entities inDokument3 SeitenBy Anandram Sankar GENERALLY, SEZ Entities Export Goods/services or Supply Goods/services To Entities inChintan VasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Opinion For Mr. Peter BanagDokument2 SeitenLegal Opinion For Mr. Peter BanagMark Avner Acosta50% (2)

- Contract of Lease (Pro Forma)Dokument4 SeitenContract of Lease (Pro Forma)iamsmileNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tax CasesDokument168 SeitenTax CasesGe LatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PNCC Vs CADokument10 SeitenPNCC Vs CADonnabel SaoiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15.1 Knights of Rizal v. DMCIDokument8 Seiten15.1 Knights of Rizal v. DMCIPau SaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 Bar Notes in LTD PDFDokument12 Seiten2017 Bar Notes in LTD PDFHiroshi CarlosNoch keine Bewertungen