Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

State Request For Restitution in Hubbard Case

Hochgeladen von

Mike CasonOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

State Request For Restitution in Hubbard Case

Hochgeladen von

Mike CasonCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

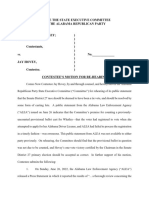

DOCUMENT 773

ELECTRONICALLY FILED

8/5/2016 4:24 PM

43-CC-2014-000565.00

CIRCUIT COURT OF

LEE COUNTY, ALABAMA

MARY B. ROBERSON, CLERK

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF LEE COUNTY, ALABAMA

STATE OF ALABAMA,

)

)

)

)

v.

)

)

)

)

MICHAEL GREGORY HUBBARD, )

)

Defendant.

)

CASE NO.

CC-2014-000565

STATES SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF

SENTENCING RECOMMENDATION

This Court requested supplemental briefing on interpreting victim in the

Restitution to Victims of Crime Act (the Act), Ala. Code 15-18-66, to include

the State. This interpretation of the Act is consistent with the statutory text and

surrounding statutes, the Acts purpose, other states interpretations of similar

statutes, and judicial economy. And it is just in this case. Interpreting the Act to

allow Hubbard and defendants like him to keep their ill-gotten gains would create a

perverse incentive for white collar criminals to engage in efficient breach-style, costbenefit analysis to determine whether the time is worth the money. This Court

should conclude that the State is the victim of Hubbards crimes under the Act and

order Hubbard to pay restitution of $1,125,000.00.

DOCUMENT 773

ARGUMENT

Restitution orders are not overturned except in cases of clear and flagrant

abuse. Ex parte Theodorou, 53 So. 3d 151, 156 (Ala. 2010) (quoting Richardson v.

State, 603 So. 2d 1132, 1134 (Ala. Crim. App. 1992)). And ordering restitution in

this case is reasonable. The State has presented the factual basis necessary to

establish the exact amount of restitution. At trial, the State introduced evidence

showing the salary Hubbard received while receiving consulting contracts and

investments from lobbyists and principals, as well as the total ill-gotten gain from

those things of value. Consistent with the evidence, the plain meaning of Ala. Code

15-18-66, and persuasive authority from other states, this Court should conclude

that the State is the victim under Ala. Code 15-18-66 and grant the State restitution

in the amount of $1,125,000.00.

I.

Interpreting victim to include the State is consistent with the

statutory text, the common meaning of person, and other states

practice.

The Act defines victim as [a]ny person whom the court determines has

suffered a direct or indirect pecuniary damage as a result of the defendants

criminal activities. Ala. Code 15-18-66 (emphasis added). Consistent with the

text of the statute, other provisions of Alabama law, and the Acts purpose, the

State can be a victim under the Act. And interpreting person to include the State

DOCUMENT 773

is consistent with other states interpretation of their statutes that identify a victim

as a person without specifically including the State.

A. Person is a legal term of art not limited to natural persons.

Under basic legal principles, the common meaning of the word person

includes the State of Alabama. For example, Blacks Law Dictionary defines

person as [a]n entity (such as a corporation) that is recognized by law as having

most of the rights and duties of a human being. Person, Blacks Law Dictionary

(10th ed. 2014). The State is well established as an entity with rights and duties,

expressly enumerated in the Alabama State Constitution. Blacks Law Dictionary

has thirty-five particularized types of person, such as natural person (defined as a

human being), and public person (defined as a sovereign government, or a body

or person delegated authority under it). Id. If the legislature had intended to limit

the definition of person to natural persons, it could have done so expressly.

And the legislature demonstrated this ability by expressly excluding

individuals who participated in the defendants criminal activities from the

definition of victim under the Act. See Ala. Code 15-18-66(4). Where a single

exclusion exists, this Court should not read additional exclusions into the statute.

Instead, this Court should give person its common legal meaning, which can

include the State.

DOCUMENT 773

B. Reading the statute in pari materia with Alabama Code Title 15 on

Criminal Procedure shows that the stated definition of person

includes the State.

The Act states the provisions of this section shall be read and deemed in

pari materia with other provisions of law. Ala. Code 15-18-78(b). Under the

in pari materia canon of statutory construction, statutes addressing the same

subject matter generally should be read as if they were one law. Wachovia Bank

v. Schmidt, 543 U.S. 303, 315-16 (2006). In the twenty-three definition sections in

Title 15, the term victim is always defined as a person or persons. See, e.g., Ala.

Code 15-14-52, 15-18-142, 15-23-3, 15-23-41, and 15-23-60. And the term

person is defined twice in Title 15: in the Alabama Crime Victims Court

Attendance Act and in the Alabama Restitution Withholding Act.

Under the Alabama Crime Victims Court Attendance Act, person

includes a government or a governmental instrumentality, including, but not

limited to, the State of Alabama or any political subdivision thereof. Ala. Code

15-14-52(1).

Under the Alabama Restitution Withholding Act, person

includes [a] government or governmental instrumentality, including, but not

limited to, the State of Alabama or any political subdivision thereof. Id. 15-18142(1)(c). These provisions, read in pari materia with the Act, show that the State

is a person under the Act and other provisions of Title 15.

DOCUMENT 773

C. Interpreting victim to include the State, making it eligible for

restitution, is reasonable, consistent with the Acts purpose, and just.

As a practical matter, the States position on restitution is reasonable,

consistent with the Acts purposes, and just. It is axiomatic that a guide to the

meaning of a statute is found in the evil which it is designed to remedy. Holy

Trinity Church v. United States, 143 U.S. 457, 463 (1892). Restitution serves not

only remedial but also rehabilitative purposes. See State v. Redmon, 885 So. 2d

850, 853 (Ala. Crim. App. 2004) ([R]estitution is . . . a measure that has both

salutary remedial and rehabilitative characteristics. Restitution is a part of the

criminal sentence rather than merely a debt between the defendant and the victim.).

Generally speaking, restitution also acts as a deterrent to future criminality.

Roberts v. State, 863 So. 2d 1149, 1155 (Ala. Ct. Crim. App. 2002) (quoting

People v. Bernal, 101 Cal. App. 4th 155, 16063 (2002)). And restitution is an

equitable remedy granted to the extent that justice between the parties requires.

United States v. Barnette, 10 F.3d 1553, 1556 (11th Cir. 1994).

In the context of a white-collar crime case, justice requires public officials to

be forbidden from keeping ill-gotten gains obtained as a result of breaching the

publics trust. As the Eleventh Circuit reasoned, if a white-collar criminal could

steal millions of dollars, place the money in an off-shore bank account, serve his

probationary sentence, and then be free to start a new life with his newly-acquired

fortune, this court sees little incentive for that person to think twice before

5

DOCUMENT 773

concocting such a scheme. United States v. Livesay, 587 F.3d 1274, 1279 (11th

Cir. 2009). Unless this Court orders restitution, Hubbard and his businesses will

continue reaping the returns from his sale of his office as Speaker even after he

serves his prison sentence.

And, without paying restitution of his ill-gotten gains, Hubbard will not be

rehabilitated from his criminal conduct.

Under the Act, rehabilitation is one

consideration courts must weigh in determining the amount of restitution to award.

Ala. Code 15-18-68(a)(3) (requiring courts to consider the anticipated

rehabilitative effect on the defendant regarding the manner of restitution or the

method of payment). Without restitution, Hubbard cannot experience the

rehabilitative effect of making the State whole for its loss of his honest services.

Pennsylvanias restitution statute, like Alabamas, does not explicitly name

the State as a potential victim. But Pennsylvania courts have interpreted victim

to include the State, considering the purposes of its restitution statute.

Pennsylvanias former House Speaker, John Perzel, was convicted based on a

course of conduct like Hubbards. The Pennsylvania court concluded that the State

was a direct victim of Perzels use of government staff, equipment, and facilities

for personal gain. Com. v. Perzel, 116 A.3d 670, 673 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2015).

Reasoning that Pennsylvanias restitution laws have dual purposes of rehabilitation

and deterrence, the Court concluded that failing to award restitution to the State

6

DOCUMENT 773

would therefore be contrary to the statutes purpose and the General Assemblys

intentnot to mention common sense. Id. at 673. Put another way, the restitution

statute both provided compensation to victims and rehabilitated defendants. Id.

Here, awarding restitution to the State would repay the State for its loss of

Hubbards honest services and would have a rehabilitative effect.

D. Interpreting victim to include the State would be consistent with

other states interpretation of their restitution statutes which define

victim as a person or persons without defining person.

The States position on restitution is also consistent with similar

interpretations in other states. For instance, a court in Indiana concluded that the

State qualifies as a victim under its restitution statutes. See Ault v. Indiana, 705

N.E.2d 1078, 1082 (Ind. Ct. App. 1999) (citing I.C. 35-50-5-3); see also

Hendrickson v. Indiana, 690 N.E.2d 765, 768 (Ind. Ct. App. 1998) (affirming

restitution to the State because public policy requires ensuring that victims are

reimbursed and defendants are prevented from being unjustly enriched by their

criminal acts.) (emphasis added). In Ault, the Court looked not to whether the

language included the State, but whether the language precluded the State from

being a victim. 705 N.E.2d at 1082.

In finding that the language did not

preclude[] the State from being found a victim, the Court in Ault found that

restitution in this case advances Indianas public policy of ensuring that victims of

criminal acts are reimbursed. Id.

7

DOCUMENT 773

Similarly, Connecticut law provides that a victim is eligible for restitution

when one person is convicted of an offense that resulted in injury to another

person. Conn. Gen. Stat. 53a-28(c). When reviewing an award to the State, a

Connecticut court determined that when the people of the State are the victim, then

[t]he people of the state cannot have fewer rights than a private victim. In re

Pellegrino, 42 B.R. 129, 134 (Bankr. D. Conn. 1984) (refusing to discharge

responsibility for restitution to the State after bankruptcy) (citing Kelly v.

Robinson, 479 U.S. 36, 5253 (1986) (recognizing that state criminal restitution

orders serve a rehabilitative and deterrent purpose and holding that restitution

owed the State was non-dischargeable in bankruptcy)).

And other states whose restitution statutes define victim with reference to

person without specifically defining person have concluded that the State is a

victim for purposes of restitution. See, e.g., Washington v. Tobin, 166 P. 3d 1167,

1168, 117074 (Wash. 2007) (en banc) (upholding restitution to the State that

included extraordinary administrative and investigatory costs); Haynes v. Alaska,

15 P.3d 1088, 1091 (Alaska Ct. App. 2001) (citing Alaska Stat. Ann. (West)

12.55.045(a)).

Interpreting the Act to include the State of Alabama in the

definition of victim would be consistent with the law in other jurisdictions

interpreting similar statutes.

DOCUMENT 773

E. While this issue is a matter of first impression, it is not

unprecedented.

Although this is a matter of first impression in Alabamas appellate courts, a

state district court ordered restitution to the State as part of a plea agreement based

on the same course of conduct as Hubbards. Plea Agreement, State v. Wren, No.

DC-14-809 (Dist. Ct. Montgomery Cty. April 1, 2016). Specifically, the Court

ordered former State Representative Greg Wren to pay restitution to the State in

the amount of $24,000. See id. at 1. And Wren paid full restitution of the $24,000

he received in consulting contracts because the State was the victim of his

dishonest services. See id. at 1. That Court accepted the plea agreement on that

theory. This Court should award restitution to the State on the same theory.1

*

Interpreting the Acts definition of victim to include the State is consistent

with the statutes text and surrounding statutes. That interpretation is consistent

with the statutes purpose. And it is consistent with other states interpretations of

their similar statutes. The State of Alabama lost Hubbards honest services when

he sold his office as Speaker for personal gain, and Hubbard should pay restitution

to the State of his ill-gotten gains.

It is also not unprecedented for the State of Alabama to be the victim of violations of

federal law by state public officials. In those case, the federal district courts awarded restitution

to the State under similar circumstances. See States Brief in Support of Sentencing

Recommendation (Doc. 756), at pp. 17-19.

9

DOCUMENT 773

II.

Awarding restitution in this case would preserve judicial economy.

At trial, the State proved the facts necessary to obtain an award of restitution.

See Ex parte Stutts, 897 So. 2d 431, 433 (Ala. 2004) (quoting Hagler v. State, 625

So. 2d 1190, 1191 (Ala. Crim. App. 1993) (holding that the trial judge need be

convinced only by a preponderance of the evidence as to whether restitution is

proper and the amount of restitution). Requiring the State to file another action

would unnecessarily burden the Court system with duplicative litigation.

And the restitution amount is up to the discretion of the trial judge and will

not be overturned except in cases of clear and flagrant abuse. Ex parte Theodorou,

53 So. 3d at 156. There is simply no need for any more litigation or judicial

proceedings on the States restitution claim. The time has come for Hubbard to

disgorge his ill-gotten gains obtained at the expense of the peoples right to honest

government.

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, the State respectfully asks this Court to enter an Order for

Restitution in the amount of $1,125,000.00, the amount of Hubbards ill-gotten

gains.

Respectfully submitted this 5th day of August 2016.

10

DOCUMENT 773

W. VAN DAVIS

ACTING ATTORNEY GENERAL

/s/ Michael B. Duffy

Michael B. Duffy

Deputy Attorney General

mduffy@ago.state.al.us

OF COUNSEL:

W. Van Davis

Supernumerary District Attorney

Acting Attorney General

423 23rd Street North

Pell City, AL 35125

vandclaw@centurylink.net

Miles M. Hart

Deputy Attorney General

mhart@ago.state.al.us

John D. Gibbs

Deputy Attorney General

jgibbs223@outlook.com

Katie Langer

Assistant Attorney General

klanger@ago.state.al.us

Megan Kirkpatrick

Assistant Attorney General

mkirkpatrick@ago.state.al.us

Kyle Beckman

Assistant Attorney General

kbeckman@ago.state.al.us

OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

STATE OF ALABAMA

501 Washington Avenue

P.O. Box 300152

Montgomery, AL 36130

11

DOCUMENT 773

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have, this the 5th day of August 2016, electronically

filed the foregoing using the AlaFile system which will send notification of such

filing to the following registered persons, and that those persons not registered with

the AlaFile system were served a copy of the foregoing by U. S. mail:

William J. Baxley

Joel E. Dillard

David McKnight

Baxley, Dillard, McKnight, James & McElroy

2700 Highway 280

Suite 110 East

Birmingham, AL 35223

bbaxley@baxleydillard.com

jdillard@baxleydillard.com

dmcknight@baxleydillard.com

R. Lance Bell

Trussell, Funderburg, Rea & Bell, P.C.

1905 1st Avenue South

Pell City, AL 35125

lance@tfrblaw.com

Phillip E. Adams, Jr.

Blake Oliver

Adams White Oliver Short & Forbus, L.L.P.

205 South 9th Street

Opelika, AL 36801

padams@adamswhite.com

boliver@adamswhite.com

/s/ Michael B. Duffy

Deputy Attorney General

12

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- EXHIBIT 071 (B) - Clearfield Doctrine in Full ForceDokument4 SeitenEXHIBIT 071 (B) - Clearfield Doctrine in Full ForceAnthea100% (2)

- Courts Are Free If You Don T Read and Learn This You Will End Up Paying Between 300 and 600 Dollars To File A Court CaseDokument5 SeitenCourts Are Free If You Don T Read and Learn This You Will End Up Paying Between 300 and 600 Dollars To File A Court CaseBar Ri88% (16)

- Dont Cite Federal LawDokument4 SeitenDont Cite Federal Lawbazyrkyr100% (1)

- What Is A State National (December 2022 Update)Dokument3 SeitenWhat Is A State National (December 2022 Update)Steven DukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- UNITED STATES Incorporated in England in 1871Dokument4 SeitenUNITED STATES Incorporated in England in 1871in1orNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trust Common Law Acting As Agents of Foreign Principal Public Notice/Public RecordDokument4 SeitenTrust Common Law Acting As Agents of Foreign Principal Public Notice/Public Recordin1or100% (4)

- Affidavit of Corporate DenialDokument9 SeitenAffidavit of Corporate DenialHOPE6578% (9)

- Explanation of These "Oaths"Dokument5 SeitenExplanation of These "Oaths"ourinstantmatterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harvard Law Review: Volume 131, Number 6 - April 2018Von EverandHarvard Law Review: Volume 131, Number 6 - April 2018Noch keine Bewertungen

- Common Law Trust Declaration Revocation Rescission Public Notice Public RecordDokument10 SeitenCommon Law Trust Declaration Revocation Rescission Public Notice Public Recordin1or100% (7)

- Barrios-Velazquez v. Asociacion De, 84 F.3d 487, 1st Cir. (1996)Dokument11 SeitenBarrios-Velazquez v. Asociacion De, 84 F.3d 487, 1st Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutes Replaced With International Law Public Notice/Public RecordDokument5 SeitenStatutes Replaced With International Law Public Notice/Public Recordin1or100% (2)

- LETTER - Massachusetts Lawyers Thru GATADokument34 SeitenLETTER - Massachusetts Lawyers Thru GATAJ. Patrick SimpsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pennsylvania Department of Health v. D. Bruce HanesDokument35 SeitenPennsylvania Department of Health v. D. Bruce Hanesjsnow489Noch keine Bewertungen

- Attachment: (For Your State, It Might Be Court Registry Investment System.)Dokument3 SeitenAttachment: (For Your State, It Might Be Court Registry Investment System.)jim88% (8)

- La Tourette v. McMaster, 248 U.S. 465 (1919)Dokument4 SeitenLa Tourette v. McMaster, 248 U.S. 465 (1919)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- WhoDoYouThinkYouAreDealingWith PDFDokument10 SeitenWhoDoYouThinkYouAreDealingWith PDFChristian Comunity100% (3)

- American Standard of Jurisdictional Hierarchy 1Dokument6 SeitenAmerican Standard of Jurisdictional Hierarchy 1LEBJNoch keine Bewertungen

- Generic Bill of ParticularsDokument7 SeitenGeneric Bill of ParticularsJohnnyLarson100% (6)

- United States Means A Federal CorporationDokument3 SeitenUnited States Means A Federal Corporationin1or100% (3)

- Generic Bill of ParticularsDokument7 SeitenGeneric Bill of Particularsamexem74Noch keine Bewertungen

- Traffic Ticket RemedyDokument6 SeitenTraffic Ticket RemedyDonald Boxley91% (35)

- Oath "REQUIRED" To Take OfficeDokument8 SeitenOath "REQUIRED" To Take Officein1or100% (7)

- Birth Certificate LawDokument24 SeitenBirth Certificate LawClyde Pointe100% (3)

- Cases Rights and LibertiesDokument0 SeitenCases Rights and LibertiesAkil Bey100% (1)

- Judiciary WordsDokument45 SeitenJudiciary Wordsmuhammad irfanNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Action Is Not Given To One Who Is Not InjuredDokument4 SeitenAn Action Is Not Given To One Who Is Not Injuredin1or100% (8)

- Alaska Marijuana Officials Warned of Legal LiabilitiesDokument5 SeitenAlaska Marijuana Officials Warned of Legal Liabilitiesenter69Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fsia Coram Non Judice ObjectionDokument5 SeitenFsia Coram Non Judice ObjectionTracy Allen Haynes Sr.80% (10)

- 004 Basic DeclarationDokument8 Seiten004 Basic DeclarationDouglas Duff100% (3)

- Octavio Jimenez-Nieves v. United States of America, 682 F.2d 1, 1st Cir. (1982)Dokument9 SeitenOctavio Jimenez-Nieves v. United States of America, 682 F.2d 1, 1st Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attorney Lisa Coogle Rambo Impersonates A JudgeDokument9 SeitenAttorney Lisa Coogle Rambo Impersonates A JudgeourinstantmatterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asset Forfeiture Rules and ProceduresDokument22 SeitenAsset Forfeiture Rules and ProceduresFinally Home RescueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accredited SovereignDokument28 SeitenAccredited Sovereignrussell_lee_1100% (2)

- United States v. Shirey, 359 U.S. 255 (1959)Dokument13 SeitenUnited States v. Shirey, 359 U.S. 255 (1959)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Beat Them at Their Own GameDokument3 SeitenHow To Beat Them at Their Own Gameerickutny100% (14)

- Lesson 4 Affidavit of TruthDokument14 SeitenLesson 4 Affidavit of TruthVernon Qumar PearsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Title Is in The Secretary of State As TrusteeDokument3 SeitenLegal Title Is in The Secretary of State As TrusteeJeff Leon100% (3)

- A Foreign Entity/The Courts/ Agency or State Cannot Bring Any Suit Against A United States Citizen Common Law Trust Public Notice Public RecordDokument4 SeitenA Foreign Entity/The Courts/ Agency or State Cannot Bring Any Suit Against A United States Citizen Common Law Trust Public Notice Public Recordstephanie harvey100% (5)

- Fair Warning Not A ThreatDokument3 SeitenFair Warning Not A ThreatBrian Kissinger100% (3)

- New Template Judicial Notice 2010Dokument25 SeitenNew Template Judicial Notice 2010Julie Hatcher-Julie Munoz Jackson100% (32)

- Clearfield Doctrine Proves Government Acts as Private CorporationDokument3 SeitenClearfield Doctrine Proves Government Acts as Private CorporationMicha Sanders97% (34)

- Final-Lawful Notification LetterDokument7 SeitenFinal-Lawful Notification LetterDavid Fields100% (1)

- 6 23 11 New Dismissal TemplateDokument12 Seiten6 23 11 New Dismissal Templatecalqlater100% (5)

- Gerald K. Adamson, Plaintiff-Appellant/cross-Appellee v. Otis R. Bowen, M.D., Secretary of Health & Human Services, Defendant - Appellee/cross-Appellant, 855 F.2d 668, 10th Cir. (1988)Dokument14 SeitenGerald K. Adamson, Plaintiff-Appellant/cross-Appellee v. Otis R. Bowen, M.D., Secretary of Health & Human Services, Defendant - Appellee/cross-Appellant, 855 F.2d 668, 10th Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- EXHIBIT 089 - NOTICE of Two National Govm - TDokument4 SeitenEXHIBIT 089 - NOTICE of Two National Govm - TDaveNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Ins. Co. v. Tidewater Co., 337 U.S. 582 (1949)Dokument55 SeitenNational Ins. Co. v. Tidewater Co., 337 U.S. 582 (1949)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lanzetta V New JerseyDokument7 SeitenLanzetta V New Jerseysheila rose lumaygayNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United StatesVon EverandThe Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United StatesNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals, Ninth CircuitDokument9 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals, Ninth CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States District Court For The Middle District of AlabamaDokument14 SeitenUnited States District Court For The Middle District of AlabamaEquality Case FilesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Overview of US Criminal Procedure and the ConstitutionVon EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Overview of US Criminal Procedure and the ConstitutionNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Constitution of the United States: A Primer for the PeopleVon EverandThe Constitution of the United States: A Primer for the PeopleBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (2)

- Was Frankenstein Really Uncle Sam? Vol Ix: Notes on the State of the Declaration of IndependenceVon EverandWas Frankenstein Really Uncle Sam? Vol Ix: Notes on the State of the Declaration of IndependenceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Identification Credentials: Mandatory or Voluntary?Von EverandIdentification Credentials: Mandatory or Voluntary?Bewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Remarks of Mr. Calhoun of South Carolina on the bill to prevent the interference of certain federal officers in elections: delivered in the Senate of the United States February 22, 1839Von EverandRemarks of Mr. Calhoun of South Carolina on the bill to prevent the interference of certain federal officers in elections: delivered in the Senate of the United States February 22, 1839Noch keine Bewertungen

- Code Breaker; The § 83 Equation: The Tax Code’s Forgotten ParagraphVon EverandCode Breaker; The § 83 Equation: The Tax Code’s Forgotten ParagraphBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- Governor's Study Group On Efficiency in State GovernmentDokument12 SeitenGovernor's Study Group On Efficiency in State GovernmentMike Cason67% (3)

- Congressional Districts Livingston PlanDokument1 SeiteCongressional Districts Livingston PlanMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aaron Cody Smith Case Supreme Court Denies WritDokument17 SeitenAaron Cody Smith Case Supreme Court Denies WritMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alabama Infant Mortality Report 2021Dokument31 SeitenAlabama Infant Mortality Report 2021Mike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clergy Letter To Governor IveyDokument8 SeitenClergy Letter To Governor IveyMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter To John Merrill On Polling Place ListDokument9 SeitenLetter To John Merrill On Polling Place ListMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clergy Letter To Governor IveyDokument8 SeitenClergy Letter To Governor IveyMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- LTR ADAH Legislators FFT 230714Dokument4 SeitenLTR ADAH Legislators FFT 230714Craig MongerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic Impact Study SummaryDokument40 SeitenEconomic Impact Study SummaryMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minority Representation ReportDokument108 SeitenMinority Representation ReportMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steve Marshall V Ethics Commission ComplaintDokument17 SeitenSteve Marshall V Ethics Commission ComplaintMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court Ruling On Aaron Cody Smith (1/11/2018)Dokument56 SeitenSupreme Court Ruling On Aaron Cody Smith (1/11/2018)Montgomery AdvertiserNoch keine Bewertungen

- COJ Judgment in Tracie Todd CaseDokument5 SeitenCOJ Judgment in Tracie Todd CaseMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gov. Kay Ivey State Vehicle MemorandumDokument1 SeiteGov. Kay Ivey State Vehicle MemorandumMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alabama Medical Cannabis Commission Map of License Application RequestsDokument1 SeiteAlabama Medical Cannabis Commission Map of License Application RequestsMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statehouse To Prison Pipeline ReportDokument25 SeitenStatehouse To Prison Pipeline ReportMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Seeking Clarity On Abortion LawDokument4 SeitenLetter Seeking Clarity On Abortion LawMike Cason100% (1)

- Road Projects From Local Grant Program Announced September 2022Dokument1 SeiteRoad Projects From Local Grant Program Announced September 2022Mike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter To Gov. Ivey On Judgeship TransferDokument4 SeitenLetter To Gov. Ivey On Judgeship TransferMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alabama Prison Bond TermsDokument33 SeitenAlabama Prison Bond TermsMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Senate Bill 184Dokument11 SeitenSenate Bill 184Mike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jay Hovey Request For RehearingDokument7 SeitenJay Hovey Request For RehearingMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spreadsheet For Proposed Alabama General Fund Budget For 2023Dokument14 SeitenSpreadsheet For Proposed Alabama General Fund Budget For 2023Mike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alabama Medical Cannabis Law SummaryDokument38 SeitenAlabama Medical Cannabis Law SummaryJohn SharpNoch keine Bewertungen

- House Bill 266Dokument11 SeitenHouse Bill 266Mike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- FactsheetDokument4 SeitenFactsheetapi-356827363Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lynda Blanchard LawsuitDokument47 SeitenLynda Blanchard LawsuitMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secretary Merrill Letter To Jeff ColemanDokument1 SeiteSecretary Merrill Letter To Jeff ColemanMike CasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Merrill Vs MilliganDokument21 SeitenMerrill Vs Milliganstreiff at redstate100% (1)

- Appeal To Supreme Court Over OSHA COVID-19 Vaccine MandateDokument54 SeitenAppeal To Supreme Court Over OSHA COVID-19 Vaccine MandateWMBF News100% (1)

- Characteristics: Wheels Alloy Aluminium Magnesium Heat ConductionDokument4 SeitenCharacteristics: Wheels Alloy Aluminium Magnesium Heat ConductionJv CruzeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 04 Activity 2Dokument2 Seiten04 Activity 2Jhon arvie MalipolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lea 201 Coverage Topics in Midterm ExamDokument40 SeitenLea 201 Coverage Topics in Midterm Examshielladelarosa26Noch keine Bewertungen

- Best Homeopathic Doctor in SydneyDokument8 SeitenBest Homeopathic Doctor in SydneyRC homeopathyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Memento Mori: March/April 2020Dokument109 SeitenMemento Mori: March/April 2020ICCFA StaffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accident Causation Theories and ConceptDokument4 SeitenAccident Causation Theories and ConceptShayne Aira AnggongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mesa de Trabajo 1Dokument1 SeiteMesa de Trabajo 1iamtheonionboiNoch keine Bewertungen

- UKBM 2, Bahasa InggrisDokument10 SeitenUKBM 2, Bahasa InggrisElvi SNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH 4 - Consolidated Techniques and ProceduresDokument18 SeitenCH 4 - Consolidated Techniques and ProceduresMutia WardaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fact Sheet Rocket StovesDokument2 SeitenFact Sheet Rocket StovesMorana100% (1)

- Human Resource Management: Chapter One-An Overview of Advanced HRMDokument45 SeitenHuman Resource Management: Chapter One-An Overview of Advanced HRMbaba lakeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Micro Controller AbstractDokument6 SeitenMicro Controller AbstractryacetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frequency Meter by C Programming of AVR MicrocontrDokument3 SeitenFrequency Meter by C Programming of AVR MicrocontrRajesh DhavaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippines Taxation Scope and ReformsDokument4 SeitenPhilippines Taxation Scope and ReformsAngie Olpos Boreros BaritugoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acceptance and Presentment For AcceptanceDokument27 SeitenAcceptance and Presentment For AcceptanceAndrei ArkovNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Jf613e) CVT Renault-Nissan PDFDokument4 Seiten(Jf613e) CVT Renault-Nissan PDFJhoanny RodríguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Market Participants in Securities MarketDokument11 SeitenMarket Participants in Securities MarketSandra PhilipNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intermediate Accounting Testbank 2Dokument419 SeitenIntermediate Accounting Testbank 2SOPHIA97% (30)

- English 8-Q3-M3Dokument18 SeitenEnglish 8-Q3-M3Eldon Julao0% (1)

- Fluke - Dry Well CalibratorDokument24 SeitenFluke - Dry Well CalibratorEdy WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shubh AmDokument2 SeitenShubh AmChhotuNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADC Driver Reference Design Optimizing THD, Noise, and SNR For High Dynamic Range InstrumentationDokument22 SeitenADC Driver Reference Design Optimizing THD, Noise, and SNR For High Dynamic Range InstrumentationAdrian SuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parasim CADENCEDokument166 SeitenParasim CADENCEvpsampathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role Played by Digitalization During Pandemic: A Journey of Digital India Via Digital PaymentDokument11 SeitenRole Played by Digitalization During Pandemic: A Journey of Digital India Via Digital PaymentIAEME PublicationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cagayan Electric Company v. CIRDokument2 SeitenCagayan Electric Company v. CIRCocoyPangilinanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nmea Components: NMEA 2000® Signal Supply Cable NMEA 2000® Gauges, Gauge Kits, HarnessesDokument2 SeitenNmea Components: NMEA 2000® Signal Supply Cable NMEA 2000® Gauges, Gauge Kits, HarnessesNuty IonutNoch keine Bewertungen

- Request Letter To EDC Used PE PipesDokument1 SeiteRequest Letter To EDC Used PE PipesBLGU Lake DanaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- STS Chapter 5Dokument2 SeitenSTS Chapter 5Cristine Laluna92% (38)

- HealthFlex Dave BauzonDokument10 SeitenHealthFlex Dave BauzonNino Dave Bauzon100% (1)

- Oscar Ortega Lopez - 1.2.3.a BinaryNumbersConversionDokument6 SeitenOscar Ortega Lopez - 1.2.3.a BinaryNumbersConversionOscar Ortega LopezNoch keine Bewertungen