Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Severe Asthma: Definition, Diagnosis and Treatment

Hochgeladen von

Halim Muhammad SatriaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Severe Asthma: Definition, Diagnosis and Treatment

Hochgeladen von

Halim Muhammad SatriaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

MEDICINE

REVIEW ARTICLE

Severe Asthma: Definition, Diagnosis

and Treatment

Marek Lommatzsch, J. Christian Virchow

SUMMARY

Background: A minority of patients with asthma have uncontrolled or partially

controlled asthma despite intensive treatment. These patients present a special

challenge because of the extensive diagnostic evaluation that they need,

insufficient evidence regarding personalized treatments, and their high

consumption of health-care resources.

Methods: The definition, diagnosis, and treatment of severe asthma are

presented on the basis of a selective literature review and the authors clinical

experience.

Results: Severe asthma is present, by definition, when adequate control of

asthma cannot be achieved by high-dose treatment with inhaled corticosteroids and additional controllers (long-acting inhaled beta 2 agonists,

montelukast, and/or theophylline) or by oral corticosteroid treatment (for at

least six months per year), or is lost when the treatment is reduced. Before any

further treatments are evaluated, differential diagnoses of asthma should be

ruled out, comorbidities should be treated, persistent triggers should be

eliminated, and patient adherence should be optimized. Moreover, pulmonary

rehabilitation is recommended in order to stabilize asthma over the long term

and reduce absences from school or work. The additional drugs that can be

used include tiotropium, omalizumab (for IgE-mediated asthma), and

azithromycin (for non-eosinophilic asthma). Antibodies against interleukin-5 or

its receptor will probably be approved soon for the treatment of severe

eosinophilic asthma.

Conclusion: The diagnosis and treatment of severe asthma is time consuming

and requires special experience. There is a need for competent treatment

centers, continuing medical education, and research on the prevalence of

severe asthma.

Cite this as:

Lommatzsch M, Virchow JC: Severe asthma: definition, diagnosis and treatment.

Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 84755. DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0847

Department of Pneumology/Interdisciplinary Intensive Care Unit, University of Rostock:

Prof. Dr. med. Lommatzsch, Prof. Dr. med. Virchow

Deutsches rzteblatt International | Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 84755

he prevalence of asthma increased significantly in

the 20th century and is currently estimated to be 5

to 10% in Europe (1). In the 20th century, the pertinent

medical concepts were dominated by the classification

of asthma as allergic asthma (evidence of allergic

sensitization) or intrinsic asthma (no evidence of

allergic sensitization); this classification was proposed

by Francis M. Rackemann in 1918 (2, 3). In the 21st

century, this is slowly being replaced by biomarkerbased phenotyping of asthma, for targeted treatment of

particular subtypes. The concept of asthma severity has

also changed: classification by lung function is giving

way to classification by degree of asthma control. This

concept has been adopted in German (www.versor

gungsleitlinien.de) and international (www.ginasthma.

com) recommendations.

In clinical practice, asthma control is assessed using

questionnaires such as the Asthma Control Test (ACT)

(Table 1) and the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ)

(4). The majority of patients can be successfully treated

with modern standard therapy. As a result, emergency

room consultations and hospitalizations of asthma

patients have decreased (5). However, the asthma of a

minority remains only partially controlled, or even uncontrolled, despite intensive treatment. This asthma,

termed severe asthma, is also important in terms of

health economics, as this minority of patients accounts

for the majority of medical resource use (6, 7).

Definition

There is no universally accepted definition of the

features that constitute severe asthma. In 2010, the

World Health Organization (WHO) recommended

that severe asthma be divided into three groups (6)

(Table 2). The advantage of the WHO classification

is its realistic assessment of patients with severe

asthma: in most cases severe asthma is not therapy

resistant but falls into one of the following three

categories (8):

Untreated asthma

Incorrectly treated asthma

Difficult-to-treat asthma (as a result of nonadherence, persistent triggers, or comorbidities)

In the current definition (2014) of severe asthma

established by a task force of the European Respiratory

Society (ERS) and the American Thoracic Society

(ATS), untreated patients (who need not necessarily

have genuinely severe asthma) are omitted. This definition

847

MEDICINE

TABLE 1

Asthma Control Test (ACT)

1 points

Everyday restriction

Daytime complaints

5 points

Most of the time

Some of the time

A little of the time

None of the time

Once a day

3 to 6 times

a week

Once or twice

a week

Not at all

During the past 4 weeks, how often did your asthma symptoms (wheezing, coughing, shortness

of breath, chest tightness or pain) wake you up at night or earlier than usual in the morning?

4 or more

nights a week

2 or 3 nights

a week

Once a

week

Once or

twice

Not at all

During the past 4 weeks, how often have you used your rescue inhaler or nebulizer medication

(such as albuterol)?

3 or more

times per day

Subjective

assessment

4 points

During the past 4 weeks, how often have you had shortness of breath?

More than

once a day

Rescue inhaler use

3 points

In the past 4 weeks, how much of the time did your asthma keep you from getting as much

done at work, school or at home?

All of the time

Nighttime complaints

2 points

1 or 2 times

per day

2 or 3 times

per week

Once a week

or less

Not at all

How would you rate your asthma control during the past 4 weeks?

Not controlled

at all

Poorly controlled

Somewhat controlled

Well controlled

Completely

controlled

In the ACT (4) five questions must be answered, and between 1 and 5 points are assigned per answer. There is thus a maximum score of 25. The definition

established by the European Respiratory Society and the American Thoracic Society in 2014 defines severe asthma as a score under 20 during high-dose ICS

(inhaled corticosteroid) therapy with an additional controller or during oral corticosteroid therapy for more than 6 months per year

TABLE 2

Classification of severe asthma according to WHO recommendation (2010) (6)

WHO class

Name

Explanation

Untreated severe asthma

Uncontrolled, as yet untreated asthma

II

Difficult-to-treat asthma

Uncontrolled asthma due to adherence problems, persistent

triggers, or comorbidities

III

Therapy-resistant asthma

Uncontrolled asthma despite maximum therapy or asthma

control that can only be maintained with maximum therapy

WHO, World Health Organization

specifies the criteria for severe asthma (7) (Box 1).

It also defines the term high-dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) (7) (Table 3). In a few cases (e.g. ciclesonide: maximum authorized daily dose 160 g in

Germany), the recommended doses in high-dose ICS

therapy can be higher than the highest daily dose established in specific countries. It is important not to forget

that the lung function-based criterion (Box 1) (forced

expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] <80%) applies

only if the Tiffeneau index (FEV1/FVC [forced vital

capacity]: a parameter of airway obstruction) is low;

this proviso is important, because restrictive lung diseases, which do not automatically make asthma more

severe, are also associated with low FEV1.

848

Diagnosis

Basic diagnostic procedures (9) includes the following:

Clinical history (Box 2)

Clinical examination

Lung function testing (spirometry or whole-body

plethysmography) followed by reversibility testing (in case of airway obstruction) or hyperreactivity testing (if there is no airway obstruction).

Allergy testing should also always be performed

(clinical history, skin prick tests, blood tests). Other

tests, such as the measurement of exhaled nitric oxide

levels (FeNO, in ppb [parts per billion]), are optional

(9). Typically, patients with severe asthma have already

had a basic assessment of their disease. In the following,

Deutsches rzteblatt International | Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 84755

MEDICINE

we describe how to proceed if a patient presents for

therapy optimization.

Confirmation of the diagnosis

If severe asthma is suspected, differential diagnoses

that may mimic asthma (Box 3) should first be ruled

out. This requires a detailed clinical history (Box 2).

Because up to 40% of asthma patients in Europe smoke

(10), subacute reversibility testing using systemic steroid therapy (e.g. prednisolone 50 mg for 7 to 14 days)

should be performed in addition to acute reversibility

testing (using a short-acting bronchodilator) to rule out

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). If

prednisolone therapy largely or completely restores

lung function, COPD is unlikely.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest may also

be useful, as it can rule out many differential diagnoses

(including malformations, dysplasias, tumors, bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, pulmonary embolism, alveolitis, and various interstitial lung diseases). The consensus paper of the ERS/ATS task force (7) therefore gives

a conditional recommendation for a chest CT in case of

atypical presentation of severe asthma. The following

procedures may also be useful:

Bronchoscopy to rule out endobronchial changes,

for biopsy, or for diagnostic bronchoalveolar

lavage

Echocardiography to rule out heart failure or

structural heart disease

24-hour pH measurement to rule out gastroesophageal reflux.

Ruling out diseases associated with asthma

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), also

known as ASA (acetylsalicylic acid) intolerance, is an

intolerance of cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 inhibitors. It is

associated with hypersensitivity to ASA, nasal polyps,

chronic sinusitis, and asthma (often severe). The exact

prevalence of AERD is uncertain and is reported as between 4 and 21% of asthma patients (37). Diagnosis

can be confirmed only using ASA provocation as there

is no valid skin or laboratory test for AERD (9).

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA)

should be suspected in the following cases:

Very high total IgE levels (usually well over

1000 kU/L)

Specific IgG and IgE antibodies to Aspergillus

fumigatus (particularly IgE antibodies to recombinant Aspergillus antigens rAsp F4 and rAsp f6)

Fleeting pulmonary opacities

Central bronchiectasis.

ChurgStrauss syndrome (CSS) should be suspected

in the following cases:

Blood eosinophils >10%

Migrating pulmonary opacities

Sinusitis

Neuropathy.

Wherever possible, suspected cases of CSS should

be further clarified by biopsy (evidence of extravascular eosinophilic infiltrations).

Deutsches rzteblatt International | Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 84755

BOX 1

The definition of severe asthma

(according to ERS/ATS 2014) (7)

During treatment with:

High-dose ICS + at least one additional controller (LABA, montelukast,

or theophylline) or

Oral corticosteroids >6 months/year

...at least one of the following occurs or would occur if treatment

would be reduced:

ACT <20 or ACQ >1.5

At least 2 exacerbations in the last 12 months

At least 1 exacerbation treated in hospital or requiring mechanical ventilation in

the last 12 months

FEV <80% (if FEV /FVC below the lower limit of normal)

1

The lower limit of normal (LLN) for FEV /FVC can be calculated using appropriate spirometer soft1

ware (www.lungfunction.org). Current recommendations advocate a FEV /FVC <LLN to detect airway

1

obstruction (40). However, if LLN is unknown, in our opinion the formerly universal limit (FEV1/FVC

<70% for adults, FEV1/FVC <75% for children) can still be used.

ICS: Inhaled corticosteroid; ACT, Asthma Control Test; ACQ: Asthma Control Questionnaire; FEV :

1

Forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC: Forced vital capacity; ERS: European Respiratory

Society; ATS: American Thoracic Society; LABA: Long-acting 2 agonist

TABLE 3

Definition of high-dose ICS therapy according to ERS/ATS consensus 2014

6 to 12 years

Beclomethasone

>12 years

800 g*

2000 g*1

320 g*

1000 g*2

Budesonide

800 g

1600 g

Ciclesonide

160 g*3

320 g

500 g

1000 g

500 g*3

800 g

Fluticasone propionate

Mometasone furoate

Doses shown are total daily doses of inhaled steroids (ICSs) which are classified as high-dose ICS therapy

according to the consensus (7) of the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the American Thoracic

Society (ATS), by age group (patients aged 6 to 12 years and those aged over 12 years).

*1

Beclomethasone dose for dry powder inhalers

*2

Beclomethasone for hydrofluoroalkane (HFA) metered-dose inhalers

*3

Not approved for children under 12 in Germany

849

MEDICINE

BOX 2

BOX 3

Content of detailed history taking for asthma

Nature, duration, and triggers of symptoms

Age at and circumstances of initial onset of symptoms

Relationship between symptoms and physical exertion and between

Diseases that may mimic asthma

Congenital or acquired immunodeficiency

Primary ciliary dyskinesia

Cystic fibrosis (CF)

Vocal cord dysfunction (VCD)

Central airway obstruction

Recurrent aspiration

Bronchiolitis

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

Psychogenic hyperventilation

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Heart failure

Drug side effects (e.g. ACE inhibitor-induced cough)

Pulmonary embolism

symptoms and occupation

Seasonality and circadian variations in symptoms

Responsiveness of symptoms to asthma-specific therapies

Changes of symptoms on travels

Active and passive smoking

Allergies and comorbidities

Family history (asthma/allergic diseases)

Regular contact with animals

Occupational or private stress factors

Tolerance of cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 inhibitors

Long-term medication, adherence, inhalation technique

Exacerbations/hospitalizations in the last 12 months

Adherence, triggers, and comorbidities

Common causes of severe asthma are poor treatment

adherence and/or persistent triggers (WHO class II:

Table 2 (8). Because of this, adherence and triggers

should always be systematically investigated (Box 4)

before additional medication is prescribed. In addition,

comorbidities that affect asthma severity, such as

chronic rhinosinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux, sleeprelated breathing disorders, or heart disease, must be

sought. Obesity can not only adversely affect asthma

control but can also be the cause of an asthma misdiagnosis, as both its symptoms and its lung function

findings can mimic asthma (7). This requires examination by a respiratory physician.

How often COPD and asthma co-occur is currently

being discussed using the term asthmaCOPD overlap

syndrome (ACOS) (www.ginasthma.com). In most

unclear cases, however, the clinical history and course

of disease indicate either COPD or asthma relatively

clearly. Evidence of a psychiatric disorderdepression

or an anxiety disorder is present in up to 50% of

patientsshould be clarified by a specialized physician

(11, 12).

Biomarkers

Allergy testing (skin prick test and/or measurement of

allergen-specific IgE antibodies) are part of standard

assessment. Total serum IgE level is required to evaluate omalizumab therapy (9). A differential blood count

is needed to identify the eosinophilic phenotype (this is

essential for specific treatment decisions (e.g. antiinterleukin-5 therapy or macrolide therapy) (13). Total

850

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme

eosinophil count in peripheral blood is the key parameter in this regard: cut-off values between 0.15

109/L (13, 14) and 0.3 109/L (15) are currently being

discussed. Systemic corticosteroid therapy makes it

impossible to ascertain patients' genuine eosinophil

status; a steroid-free interval can be considered in such

cases. The ERS/ATS consensus paper gives a conditional recommendation against asthma management

using FeNO measurement (7). Persistently high FeNO

levels (above 50 ppb) during high-dose ICS therapy,

however, may indicate poor adherence, persistent exposure to allergens, or strong intrinsic disease activity (16).

Treatment

The details of standard therapy can be found in the

asthma guidelines (17) and the German National Disease Management Guideline. Basic therapy consists of

an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), to which additional

controllers are added if asthma control is inadequate: an

inhaled long-acting beta 2 agonist (LABA), montelukast, and/or theophylline. If this therapy does not

adequately control asthma, oral corticosteroids (e.g.

prednisolone) are added. Specific immunotherapy for

severe asthma is only a theoretical possibility, for the

following reasons (18, 19):

Either there is no detectable allergen or there is

polysensitization with no clear relationship between allergen exposure and symptoms.

Lung function is often too poor (immunotherapy

requires FEV1 >70% for safety reasons).

There is a lack of randomized clinical trials on

severe asthma.

Deutsches rzteblatt International | Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 84755

MEDICINE

BOX 4

Systematic assessment of adherence

and persistent triggers

Does the patient understand the concept of inhaled therapy for asthma control?

Is the patient receiving basic inhaled therapy according

to guidelines and adapted to the severity of his/her

asthma?

TABLE 4

Treatment principles for diseases associated with asthma

Disease

Abbreviation

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory AERD

disease (ASA intolerance)

Lifelong ASA therapy (at least

300 mg/day); treatment must be

begun on an inpatient basis (37)

Allergic bronchopulmonary

aspergillosis

ABPA

Systemic corticosteroid therapy

beginning with 0.5 to 0.75 mg prednisolone equivalent per kg body

weight and then tapering down;

concomitant antimycotic therapy

(itraconazole, alternatively voriconazole if itraconazole not tolerated)

in case of recurrent exacerbations

(7, 38)

ChurgStrauss syndrome

CSS

Corticosteroid plus an additional

immunosuppressant (methotrexate,

cyclophosphamide, or azathioprine); after high-dose initial

therapy, reduce gradually to lowest

possible long-term therapy (39)

Does the patient handle his/her inhaler(s) correctly?

(If not, who trains the patient and who monitors the

success of training?)

Does the patient take inhaled therapy regularly? (If not,

how can this be optimized on an individual basis?)

Does the patient avoid active and passive smoking?

Does the patient know his/her allergen spectrum and

does he/she effectively avoid these allergens?

Does the patient avoid detrimental medications (e.g. be-

Treatment principles

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid

ta blockers for which there are treatment alternatives)?

Although patients with severe asthma are often deficient in vitamin D, current evidence does not support

a universal recommendation of vitamin D therapy (20).

There are specific treatment principles for the diseases

associated with asthma (Table 4). Below we outline

basic measures and additional treatment options following a diagnosis of severe asthma.

may not consider it worth reporting. Eliminating

sources of allergens (e.g. cats) can be even more difficult, due to emotional obstacles. One underestimated

challenge is the elimination of occupational allergens,

the avoidance of which may threaten patients emotionally as well as economically (e.g. a baker working in a

family-owned bakery).

Basic therapy

Therapy for comorbidities

For obese patients, weight reduction can have a

positive effect on asthma control (22). Chronic rhinosinusitis is an important trigger of asthma and should be

investigated and properly treated by a specialized

physician; there is a guideline on this subject (ARIA:

Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma) (23).

Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

also requires treatment, as does depression or an

anxiety disorder (11, 12).

Optimizing inhaled therapy

Poor inhalation technique and poor adherence are common and very straightforward causes of uncontrolled

asthma. Where necessary, patients must be re-educated

and retrained; resources for this include freely available

online videos (approximately 2 to 3 minutes per video)

(www.atemwegsliga.de). Whether switching to inhalers

with extrafine formulations (average particle size 1 to

3m) can improve asthma control by means of better

ICS deposition in the smaller airways is currently under

discussion (21). Optimized patientinhaler interaction

is an essential key to successful inhaled therapy. Therefore, patients should be involved in inhaler selection

(e.g. dry powder or metered-dose inhaler). Finally,

check whether the maximum daily ICS dose stated in

international recommendations has been prescribed

(Table 3).

Eliminating persistent triggers

Persistent asthma triggers are a common feature of

difficult-to-treat asthma (WHO class II). Identifying

persistent (often perennial and/or domestic) sources of

allergens can be challenging. Allergens may be uncommon, or exposure may not be obvious and the patient

Deutsches rzteblatt International | Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 84755

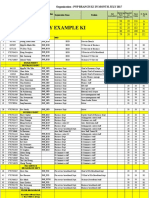

Additional treatment options

If the basic therapeutic measures mentioned above

have been exhausted, additional treatment options

that serve in particular to reduce oral and inhaled

corticosteroid doses should be evaluated. In general,

the evidence advocating these additional options is

weak (7), as there are only a few clinical trials on

severe asthma that address each one specifically. As a

result, in everyday clinical practice treatment decisions

can often be made only on the basis of experience and

outcomes in similar circumstances. Treatment options

can be divided into two groups according to whether

or not they can be begun without further phenotyping

(Figure 1).

851

MEDICINE

FIGURE 1

High-dose ICS therapy with additional controllers (LABA, montelukast and/or theophylline) or oral corticosteroid therapy

>6 months per year, without achieving asthma control or with loss of control on therapy reduction

Consider referring to specialized physician

Any other disease?

Any asthma-associated disease (ABPA, CSS, AERD)?

Yes

Treat underlying disease

Yes

Eliminate triggers

Treat comorbidities

Increase adherence

Inhaler training or selection of inhaler

that may be more suitable for patient

No

Persistent triggers or comorbidities?

Infrequent therapy use by patient?

Problems handling the inhaler?

No

No phenotyping

Rehabilitation

Tiotropium

Evaluate additional

treatment options

Aim to include patient in a

severe asthma registry

Phenotyping

IgE-mediated asthma: omalizumab

Eosinophilic asthma: anti-IL5 therapy*1

Noneosinophilic asthma: azithromycin*2

Diagnosing and treating severe asthma

*1 Currently possible in Germany only within clinical trials

*2 In case of low eosinophil count (<0.2 109/L during cessation of systemic corticosteroid therapy) and considering contraindications for

macrolide therapy

ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta 2 agonist; ABPA, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; CSS, ChurgStrauss syndrome;

AERD, aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (ASA intolerance); IgE, immunoglobulin E; IL, interleukin

Rehabilitation

For most patients, asthma requires lifelong medical

care which cannot be optimally provided on an

outpatient basis or in acute-care hospitals. Inpatient

rehabilitation in appropriate specialized facilities is,

therefore, recommended. This is particularly important

in patients with severe asthma, in whom additional

psychosocial or socioeconomic factors often contribute

to asthma severity (24, 25). Rehabilitation aids in

incorporating therapeutic needs into daily routine

and provides patients with knowledge of their

disease that allows them to organize their daily lives.

Rehabilitation can stabilize asthma in the long term,

significantly reduce resource consumption, and

result in fewer hospitalizations and days off school

or work (26).

852

Long-acting anticholinergics

The usefulness of long-acting muscarinic antagonists

(LAMAs) is obvious, because it is primarily the parasympathetic nervous system that controls airway tone

(27) (Figure 2). Three placebo-controlled clinical trials

all showed that additional tiotropium therapy improved

asthma patients lung function (mean FEV1 increase

approximately 100 mL greater than the placebo effect)

and reduced their number of exacerbations. These

patients had had persistent symptoms and at least one

exacerbation treated with systemic corticosteroids in

the last 12 months despite high-dose ICS/LABA therapy (ICS dose 800 g budesonide equivalent) (28,

29). Tiotropium was therefore approved for asthma

patients in Germany, with this restriction (medium- or

high-dose ICS/LABA combination therapy, at least one

Deutsches rzteblatt International | Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 84755

MEDICINE

FIGURE 2

Epithelium

Smooth

muscle

LAMA

M3

Parasympathetic

nervous system

LABA

Neuronal control of airway tone and

effect of bronchodilators (simplified).

In parasympathetic ganglia in the airway

wall, preganglionic parasympathetic nerve

fibers (from the vagus nerve) synapse on

postganglionic parasympathetic neurons

that lead to bronchoconstriction by releasing

acetylcholine (mediated in particular by the

M3 receptor on the airway smooth muscle).

Postganglionic sympathetic fibers do not

innervate the human airway smooth muscle

but affect airway tone indirectly (via innervation of the parasympathetic ganglia and

control of vessel permeability and catecholamine release). Long-acting muscarinic

antagonists (LAMAs) lead to bronchodilation

by inhibiting muscarinic receptors (particularly the M3 receptor). Long-acting beta 2

agonists (LABAs) cause bronchodilation in

particular by stimulating beta 2 receptors on

the smooth muscle of the airways (27)

2

Vessels

exacerbation treated with systemic corticosteroids in

the last 12 months), in September 2014. No clinical

trials of other anticholinergics (glycopyrronium, aclidinium, umeclidinium) have yet been published for the

indication severe asthma.

Anti-IgE therapy

For patients with severe allergic asthma, additional

treatment with the anti-IgE antibody omalizumab leads

to a reduction (by 50%) in the number of severe exacerbations, improved asthma control and quality of life

(30), and reduced need for corticosteroids: the average

daily dose of prednisolone falls from 15.5 mg to 5.8 mg

(31). Omalizumab therapy is safe (32) but is expensive.

Omalizumab is administered subcutaneously every 2 to

4 weeks and is approved for the treatment of asthma,

provided the following conditions are all met:

Persistent symptoms and recurrent exacerbations

despite high-dose ICS/LABA therapy

FEV1 <80%

Sensitization to perennial airborne allergens

Total serum IgE between 30 and 1500 kU/L (although the upper limit is lower for body weights

above 50 kg: see summary of product characteristics).

If there is no improvement within four months of

therapy, a subsequent response is unlikely (7). Omalizumab can be as effective in intrinsic asthma (patients

with no evidence of allergy) as in allergic asthma (3) but is

approved only for the latter. Such off-label use of omalizumab to treat intrinsic asthma should be evaluated on a

case-by-case basis in an experienced asthma center.

Deutsches rzteblatt International | Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 84755

Sympathetic

nervous system

Macrolides

Because of their immunomodulating effects, the use of

macrolides in asthma has been discussed for years. In a

clinical trial, azithromycin (3 250 mg per week;

initially 250 mg per day for five days) reduced the risk

of an exacerbation by 46% in severe noneosinophilic

asthma, but not in eosinophilic asthma (33). Because

this therapy has potential serious side effects (ototoxicity, QT interval prolongation, macrolide resistance),

and because there is only one positive trial, the current

ERS/ATS consensus paper gives a conditional recommendation against long-term macrolide therapy for severe asthma (7). As there are no specific alternative

treatment options for noneosinophilic asthma, however,

we believe that azithromycin therapy can be considered

as a last resort if a patient with a low eosinophil count

(less than 0.2 109/L in the absence of systemic corticosteroid therapy) suffers from frequent exacerbations.

Potential future treatment options

The phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor roflumilast has

shown clinical efficacy in asthma (34), but trials

exploring the role of roflumilast as an additional treatment option for severe asthma are lacking. Despite

some positive clinical studies, thermoplasty (endobronchial radiofrequency ablation through a dedicated

catheter) should be performed only within clinical trials

or independent registries (7). The use of antibodies targeting interleukin-5 (mepolizumab, reslizumab) or its

receptor (benralizumab) is currently being investigated

in phase III trials in patients with eosinophilic asthma

(14, 15, 35). As yet, patients can only be treated with

853

MEDICINE

anti-IL5 antibodies or anti-IL5 receptor antibodies as

part of clinical trials. This treatment is expected to be

approved in Germany for severe eosinophilic asthma in

the near future. Th2 cytokine antagonists (lebrikizumab, tralokinumab, dupilumab) are currently undergoing clinical development (35).

Requirements for treatment optimization

The treatment of patients with severe asthma requires

experience, is time-consuming, and often necessitates

off-label drug use. As a result, severe asthma is sometimes inadequately diagnosed and treated (36). In our

view, this situation makes the following desirable:

Inclusion of as many patients as possible in severe

asthma registries such as www.german-asthmanet.de

Better coverage of the diagnosis and treatment of

severe asthma in physicians training

Assessment of patients with severe asthma in

specialized asthma centers, in order to give them

the opportunity to participate in clinical trials.

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Lommatzsch has received consultancy and lecture fees and reimbursement of travel and participation costs from Allergopharma, Astra Zeneca,

Bencard, Berlin-Chemie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Janssen-Cilag,

MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Nycomed/Takeda, TEVA, and UCB. He has also

received fees for commissioned clinical trials from Astra Zeneca and research

funding from GSK.

Prof. Virchow has received consultancy and lecture fees and reimbursement of

travel and participation costs from Allergopharma, Astra Zeneca, Avontec,

Bayer, Bencard, Berlin-Chemie, Bionorica, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi,

Essex/Schering-Plough, GSK, Janssen-Cilag, Leti, MEDA, Merck, MSD,

Mundipharma, Novartis, Nycomed/Takeda, Pfizer, Revotar, Roche, SanofiAventis, Sandoz-Hexal, Stallergens, TEVA, UCB, and Zydus/Cadila. He has also

received research funding from GSK and MSD.

A precise definition of the term severe asthma was

proposed by a task force of the ERS and ATS in 2014.

The basic steps in the treatment of severe asthma are

confirmation of the diagnosis, treatment for comorbidities, elimination of persistent triggers, and optimization

of adherence.

Rehabilitation and tiotropium, omalizumab, or azithromycin therapy are additional treatment options for

severe asthma.

It is expected that antibodies targeting interleukin-5 or

its receptor will be approved for the treatment of severe

eosinophilic asthma in the near future.

There is a need for research on the prevalence of

severe asthma, for asthma competence centers, and for

continuing education for physicians.

9. Lommatzsch M, Virchow JC: Asthma-Diagnostik: aktuelle Konzepte

und Algorithmen. Allergologie 2012; 35: 45467.

10. To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, et al.: Global asthma prevalence in

adults: Findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC

public health 2012; 12: 204.

11. Vamos M, Kolbe J: Psychological factors in severe chronic asthma.

Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1999; 33: 53844.

12. Heaney LG, Conway E, Kelly C, Gamble J: Prevalence of psychiatric

morbidity in a difficult asthma population: Relationship to asthma

outcome. Respir Med 2005; 99: 11529.

13. Katz LE, Gleich GJ, Hartley BF, Yancey SW, Ortega HG: Blood

eosinophil count is a useful biomarker to identify patients with

severe eosinophilic asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014; 11: 5316.

Manuscript received on 30 May 2014, revised version accepted on

11 September 2014.

14. Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, et al.: Mepolizumab treatment in

patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:

1198207.

Translated from the original German by Caroline Devitt, M.A.

15. Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, et al.: Mepolizumab for severe

eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): A multicentre, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 6519.

REFERENCES

1. Sears MR: Trends in the prevalence of asthma. Chest 2014; 145:

21925.

2. Rackemann FM: A clinical study of one hundred and fifty cases of

bronchial asthma. Arch Intern Med 1918; 12: 51752.

3. Lommatzsch M, Korn S, Buhl R, Virchow JC: Against all odds: AntiIgE for intrinsic asthma? Thorax 2014; 69: 946.

4. Jia CE, Zhang HP, Lv Y, et al.: The asthma control test and asthma

control questionnaire for assessing asthma control: Systematic

review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131:

695703.

5. Rowe BH, Voaklander DC, Wang D, et al.: Asthma presentations by

adults to emergency departments in Alberta, Canada: A large

population-based study. Chest 2009; 135: 5765.

6. Bousquet J, Mantzouranis E, Cruz AA, et al.: Uniform definition of

asthma severity, control, and exacerbations: Document presented

for the World Health Organization consultation on severe asthma.

J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126: 92638.

7. Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al.: International ERS/ATS

guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma.

Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 34373.

8. Bush A, Pavord ID: Omalizumab: NICE to USE you, to LOSE you

NICE. Thorax 2013; 68: 78.

854

KEY MESSAGES

16. Dweik RA, Boggs PB, Erzurum SC, et al.: An official ATS clinical

practice guideline: Interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels

(FeNO) for clinical applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;

184: 60215.

17. Buhl R, Berdel D, Criee CP, et al.: [Guidelines for diagnosis and

treatment of asthma patients]. Pneumologie 2006; 60: 13977.

18. Abramson MJ, Puy RM, Weiner JM: Injection allergen immunotherapy for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; CD001186.

19. Kleine-Tebbe J, Bufe A, Ebner C, et al.: Die spezifische Immuntherapie (Hyposensibilisierung) bei IgE-vermittelten allergischen

Erkrankungen. Allergo J 2009; 18: 50837.

20. Castro M, King TS, Kunselman SJ, et al.: Effect of vitamin D3 on

asthma treatment failures in adults with symptomatic asthma and

lower vitamin D levels: The VIDA randomized clinical trial. JAMA

2014; 311: 208391.

21. van den Berge M, ten Hacken NH, van der Wiel E, Postma DS:

Treatment of the bronchial tree from beginning to end: Targeting

small airway inflammation in asthma. Allergy 2013; 68: 1626.

22. Dias-Junior SA, Reis M, de Carvalho-Pinto RM, Stelmach R, Halpern

A, Cukier A: Effects of weight loss on asthma control in obese

patients with severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 136877.

Deutsches rzteblatt International | Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 84755

MEDICINE

23. Bousquet J, Schunemann HJ, Samolinski B, et al.: Allergic rhinitis

and its impact on asthma (ARIA): Achievements in 10 years and

future needs. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 130: 104962.

24. Kolbe J, Vamos M, Fergusson W: Socio-economic disadvantage,

quality of medical care and admission for acute severe asthma.

Aust N Z J Med 1997; 27: 294300.

25. Wainwright NW, Surtees PG, Wareham NJ, Harrison BD: Psychosocial factors and incident asthma hospital admissions in the EPICNorfolk cohort study. Allergy 2007; 62: 55460.

26. Rochester CL, Fairburn C, Crouch RH: Pulmonary rehabilitation for

respiratory disorders other than chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease. Clin Chest Med 2014; 35: 36989.

27. Proskocil BJ, Fryer AD: Beta2-agonist and anticholinergic drugs in

the treatment of lung disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2005; 2:

30510; discussion 112.

28. Kerstjens HA, Disse B, Schroder-Babo W, et al.: Tiotropium improves

lung function in patients with severe uncontrolled asthma: A randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128:

30814.

29. Kerstjens HA, Engel M, Dahl R, et al.: Tiotropium in asthma poorly

controlled with standard combination therapy. N Engl J Med 2012;

367: 1198207.

30. Humbert M, Beasley R, Ayres J, et al.: Benefits of omalizumab as

add-on therapy in patients with severe persistent asthma who are

inadequately controlled despite best available therapy (GINA 2002

step 4 treatment): INNOVATE. Allergy 2005; 60: 30916.

31. Braunstahl GJ, Chen CW, Maykut R, Georgiou P, Peachey G, Bruce

J: The experience registry: the real-world' effectiveness of omalizumab in allergic asthma. Respir Med 2013; 107: 114151.

32. Busse W, Buhl R, Fernandez Vidaurre C, et al.: Omalizumab and the

risk of malignancy: Results from a pooled analysis. J Allergy Clin

Immunol 2012; 129: 9839.

33. Brusselle GG, Vanderstichele C, Jordens P, et al.: Azithromycin for

prevention of exacerbations in severe asthma (AZISAST): A multi-

Deutsches rzteblatt International | Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 84755

centre randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Thorax

2013; 68: 3229.

34. Bousquet J, Aubier M, Sastre J, et al.: Comparison of roflumilast, an

oral anti-inflammatory, with beclomethasone dipropionate in the

treatment of persistent asthma. Allergy 2006; 61: 728.

35. Hambly N, Nair P: Monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of

refractory asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2014; 20: 8794.

36. Sachverstndigenrat zur Begutachtung der Entwicklung im Gesundheitswesen: www.svr-gesundheit.de, Gutachten 2000/2001,

Kurzfassungen Band III (ber-, Unter- und Fehlversorgung),

Abschnitt 10.3.2 Asthma.

37. Kowalski ML, Makowska JS, Blanca M, et al.: Hypersensitivity to

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)classification,

diagnosis and management: Review of the EAACI/ENDA(#) and

GA2LEN/HANNA*. Allergy 2011; 66: 81829.

38. Patterson K, Strek ME: Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

Proc Am Thorac Soc 2010; 7: 23744.

39. Bosch X, Guilabert A, Espinosa G, Mirapeix E: Treatment of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis: A systematic

review. JAMA 2007; 298: 65569.

40. Quanjer PH, Brazzale DJ, Boros PW, Pretto JJ: Implications of

adopting the global lungs initiative 2012 all-age reference

equations for spirometry. Eur Respir J 2013; 42: 104654.

Corresponding author:

Prof. Dr. med. Marek Lommatzsch

Abteilung fr Pneumologie/Interdisziplinre Internistische Intensivstation

Medizinische Klinik I

Universittsmedizin Rostock

Ernst-Heydemann-Str. 6

18057 Rostock, Germany

marek.lommatzsch@med.uni-rostock.de

855

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Asthma in the 21st Century: New Research AdvancesVon EverandAsthma in the 21st Century: New Research AdvancesRachel NadifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 5A: Dental Management of Patients With Asthma: Prepared By: Dr. Maria Luisa Ramos - ClementeDokument27 SeitenModule 5A: Dental Management of Patients With Asthma: Prepared By: Dr. Maria Luisa Ramos - Clementeelaine100% (1)

- Restrictive Lung DiseaseDokument32 SeitenRestrictive Lung DiseaseSalman Khan100% (1)

- Cor PulmonaleDokument8 SeitenCor PulmonaleAymen OmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bronchial Asthma and Acute AsthmaDokument38 SeitenBronchial Asthma and Acute AsthmaFreddy KassimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asthma: Pio T. Esguerra II, MD, FPCP, FPCCP Pulmonary & Critical Care FEU-NRMF Medical CenterDokument98 SeitenAsthma: Pio T. Esguerra II, MD, FPCP, FPCCP Pulmonary & Critical Care FEU-NRMF Medical CenteryayayanizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GP Reg - Asthma and Spirometry 2011Dokument114 SeitenGP Reg - Asthma and Spirometry 2011minerva_stanciuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Severe AsthmaDokument19 SeitenAcute Severe AsthmaDurgesh PushkarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pulmonary EosinophiliaDokument19 SeitenPulmonary EosinophiliaOlga GoryachevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rheumatic Fever: DR: Kaem Shir AliDokument24 SeitenRheumatic Fever: DR: Kaem Shir AliMwanja Moses100% (1)

- Asthma and CopdDokument44 SeitenAsthma and CopdBeer Dilacshe100% (1)

- Dr. Sana Bashir DPT, MS-CPPTDokument46 SeitenDr. Sana Bashir DPT, MS-CPPTbkdfiesefll100% (1)

- Case Discussion - CopdDokument63 SeitenCase Discussion - CopdrajeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Copd PDFDokument28 SeitenCopd PDFDarawan MirzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approach To A Non-Resolving PnemoniaDokument20 SeitenApproach To A Non-Resolving PnemoniaFelix ManyerukeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Respiratory Path PathophysiologyDokument25 SeitenRespiratory Path Pathophysiologyaiadalkhalidi100% (1)

- Resp Bronch N LaDokument56 SeitenResp Bronch N LaMansi GandhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Non Resolving Pneumonia: by DR - Lokesh.L.V Moderators DR Mohan - Rao AND DR UmamaheshwariDokument58 SeitenNon Resolving Pneumonia: by DR - Lokesh.L.V Moderators DR Mohan - Rao AND DR Umamaheshwaridrlokesh100% (5)

- COPDDokument73 SeitenCOPDBroken OreosNoch keine Bewertungen

- COPD ExacerbationDokument2 SeitenCOPD ExacerbationjusthoangNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Management of Acute Respiratory Distress SyndromeDokument48 SeitenThe Management of Acute Respiratory Distress SyndromeLauraAlvarezMulettNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pneumonias: Associate Professor Dr. Lauren Ţiu ŞorodocDokument60 SeitenThe Pneumonias: Associate Professor Dr. Lauren Ţiu ŞorodocCristina Georgiana CoticăNoch keine Bewertungen

- COPD Lecture Slides For BlackBoardDokument52 SeitenCOPD Lecture Slides For BlackBoardClayton JensenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mucormycosis in Covid 19Dokument2 SeitenMucormycosis in Covid 19Editor IJTSRDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asthma Lancet 23febDokument18 SeitenAsthma Lancet 23febMr. LNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Management of Allergic RhinitisDokument80 SeitenFinal Management of Allergic RhinitisgimamrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bronchial AsthmaDokument46 SeitenBronchial AsthmaKhor Kee GuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pneumonia: DefinitionDokument5 SeitenPneumonia: DefinitionhemaanandhyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sleep Apnoea - Prof - DR K.K.PDokument44 SeitenSleep Apnoea - Prof - DR K.K.PjialeongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Referat Batuk NurfitriDokument45 SeitenReferat Batuk NurfitribellabelbonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caseous Pneumonia: by Makarova Elena AlexandrovnaDokument16 SeitenCaseous Pneumonia: by Makarova Elena AlexandrovnaAMEER ALSAABRAWINoch keine Bewertungen

- GINA 2014 ShortcutDokument44 SeitenGINA 2014 ShortcutKath Dellosa100% (1)

- Different Types of AsthmaDokument16 SeitenDifferent Types of AsthmaAmira Saidin0% (1)

- Drugs For Cough and Bronchial AsthmaDokument47 SeitenDrugs For Cough and Bronchial AsthmaNavlika DuttaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lung AuscultationDokument62 SeitenLung AuscultationOlea CroitorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ischemic Heart DiseaseDokument116 SeitenIschemic Heart DiseaseAndrew OrlovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Copd 200412082048Dokument139 SeitenCopd 200412082048Richard ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmacotherapy of PneumoniaDokument56 SeitenPharmacotherapy of Pneumoniahoneylemon.co100% (1)

- Asthma MedicationDokument6 SeitenAsthma Medicationmomina arshidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagnosis of PneumoconiosisDokument55 SeitenDiagnosis of PneumoconiosiselsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cerebral InfarctionDokument2 SeitenCerebral InfarctionMarie Aurora Gielbert MarianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- COPD HarrisonsDokument45 SeitenCOPD HarrisonsNogra CarlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Onchial AsthmaDokument13 SeitenOnchial Asthmaram krishna100% (1)

- Lung Sounds: An Assessment of The Patient in Respiratory DistressDokument40 SeitenLung Sounds: An Assessment of The Patient in Respiratory DistressJoseph Rodney de LeonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pulmonary Sarcoidosis Presenting With Cannonball Pattern Mimicking Lung MetastasesDokument5 SeitenPulmonary Sarcoidosis Presenting With Cannonball Pattern Mimicking Lung MetastasesIJAR JOURNALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chronic Obstructive Lung Diseases and Chronic Restrictive Lung DiseasesDokument59 SeitenChronic Obstructive Lung Diseases and Chronic Restrictive Lung DiseasesGEORGENoch keine Bewertungen

- Asthma: Diagnosis and Treatment GuidelineDokument27 SeitenAsthma: Diagnosis and Treatment GuidelineDinar Riny Nv100% (1)

- Approach To The Patient With Cough and Hemoptysis 15 11 13Dokument34 SeitenApproach To The Patient With Cough and Hemoptysis 15 11 13Sanchit PeriwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- AtaxiaDokument8 SeitenAtaxiaDivya Gupta0% (1)

- Primary Pulmonary TuberculosisDokument4 SeitenPrimary Pulmonary TuberculosisdocdorkmeNoch keine Bewertungen

- PneumoniaDokument48 SeitenPneumoniaSiti FatimahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Respiratory Failure PresentationDokument13 SeitenRespiratory Failure PresentationHusnain Irshad AlviNoch keine Bewertungen

- ByssinosisDokument32 SeitenByssinosisKaren KuniyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Respiratory EmergenciesDokument34 SeitenRespiratory EmergenciesRoshana MallawaarachchiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approach To Interstitial Lung Disease 1Dokument33 SeitenApproach To Interstitial Lung Disease 1MichaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- BronchiolitisDokument12 SeitenBronchiolitisEz BallNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tuberculosis: Communicable DiseaseDokument6 SeitenTuberculosis: Communicable DiseaseMiguel Cuevas DolotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bronchial AsthmaDokument21 SeitenBronchial AsthmashaitabliganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drug Resistant TuberculosisDokument58 SeitenDrug Resistant TuberculosisbharatnarayananNoch keine Bewertungen

- WHO MDR 2020 Handbook Treatment PDFDokument88 SeitenWHO MDR 2020 Handbook Treatment PDFYuanita GunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conjunctivitis Infectious NoninfectiousDokument10 SeitenConjunctivitis Infectious NoninfectiousHalim Muhammad SatriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neurological Complications of CKDDokument10 SeitenNeurological Complications of CKDHalim Muhammad SatriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bulking For EctomorphsDokument45 SeitenBulking For EctomorphsSixp8ck100% (1)

- Tri-Phase TrainingDokument49 SeitenTri-Phase TrainingSixp8ck100% (1)

- VaccinationDokument31 SeitenVaccinationHalim Muhammad SatriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ageing and OsteoarthritisDokument9 SeitenAgeing and OsteoarthritisHalim Muhammad SatriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypertensive Crisis - ClinicalKeyDokument29 SeitenHypertensive Crisis - ClinicalKeyHalim Muhammad SatriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heart Failure and Kidney DysfunctionDokument14 SeitenHeart Failure and Kidney DysfunctionHalim Muhammad SatriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of Supply Chain Management A Balanced Approach 4th Edition Wisner Solutions ManualDokument36 SeitenPrinciples of Supply Chain Management A Balanced Approach 4th Edition Wisner Solutions Manualoutlying.pedantry.85yc100% (28)

- Fortigate Firewall Version 4 OSDokument122 SeitenFortigate Firewall Version 4 OSSam Mani Jacob DNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACCA F2 2012 NotesDokument18 SeitenACCA F2 2012 NotesThe ExP GroupNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fake News Infographics by SlidesgoDokument33 SeitenFake News Infographics by SlidesgoluanavicunhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pelayo PathopyhsiologyDokument13 SeitenPelayo PathopyhsiologyE.J. PelayoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Raksha Mantralaya Ministry of DefenceDokument16 SeitenRaksha Mantralaya Ministry of Defencesubhasmita sahuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benefits and Limitations of BEPDokument2 SeitenBenefits and Limitations of BEPAnishaAppuNoch keine Bewertungen

- PetrifiedDokument13 SeitenPetrifiedMarta GortNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stonehell Dungeon 1 Down Night Haunted Halls (LL)Dokument138 SeitenStonehell Dungeon 1 Down Night Haunted Halls (LL)some dude100% (9)

- PNP Ki in July-2017 AdminDokument21 SeitenPNP Ki in July-2017 AdminSina NeouNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Wren-Lewis - NDEDokument7 SeitenJohn Wren-Lewis - NDEpointandspaceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Verniers Micrometers and Measurement Uncertainty and Digital2Dokument30 SeitenVerniers Micrometers and Measurement Uncertainty and Digital2Raymond ScottNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 20 AP QuestionsDokument6 SeitenChapter 20 AP QuestionsflorenciashuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preparing For CPHQ .. An Overview of Concepts: Ghada Al-BarakatiDokument109 SeitenPreparing For CPHQ .. An Overview of Concepts: Ghada Al-BarakatiBilal SalamehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Sumer Flip BookDokument9 SeitenAncient Sumer Flip Bookapi-198624210Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 5 - CheerdanceDokument10 SeitenChapter 5 - CheerdanceJoana CampoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bgrim 1q2022Dokument56 SeitenBgrim 1q2022Dianne SabadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lect2 - 1151 - Grillage AnalysisDokument31 SeitenLect2 - 1151 - Grillage AnalysisCheong100% (1)

- Survivor's Guilt by Nancy ShermanDokument4 SeitenSurvivor's Guilt by Nancy ShermanGinnie Faustino-GalganaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GLOBE2Dokument7 SeitenGLOBE2mba departmentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Persuasive Speech 2016 - Whole Person ParadigmDokument4 SeitenPersuasive Speech 2016 - Whole Person Paradigmapi-311375616Noch keine Bewertungen

- Iec Codes PDFDokument257 SeitenIec Codes PDFAkhil AnumandlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Possessive Determiners: A. 1. A) B) C) 2. A) B) C) 3. A) B) C) 4. A) B) C) 5. A) B) C) 6. A) B) C) 7. A) B) C)Dokument1 SeitePossessive Determiners: A. 1. A) B) C) 2. A) B) C) 3. A) B) C) 4. A) B) C) 5. A) B) C) 6. A) B) C) 7. A) B) C)Manuela Marques100% (1)

- Academic Socialization and Its Effects On Academic SuccessDokument2 SeitenAcademic Socialization and Its Effects On Academic SuccessJustin LargoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Teachers' Journey: Phenomenological Study On The Puritive Behavioral Standards of Students With Broken FamilyDokument11 SeitenA Teachers' Journey: Phenomenological Study On The Puritive Behavioral Standards of Students With Broken FamilyNova Ariston100% (2)

- Report DR JuazerDokument16 SeitenReport DR Juazersharonlly toumasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Green Dot ExtractDokument25 SeitenGreen Dot ExtractAllen & UnwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Low Voltage Switchgear Specification: 1. ScopeDokument6 SeitenLow Voltage Switchgear Specification: 1. ScopejendrikoNoch keine Bewertungen

- GCP Vol 2 PDF (2022 Edition)Dokument548 SeitenGCP Vol 2 PDF (2022 Edition)Sergio AlvaradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measurement and Scaling Techniques1Dokument42 SeitenMeasurement and Scaling Techniques1Ankush ChaudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossVon EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsVon EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeVon EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityVon EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (24)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaVon EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (42)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedVon EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (80)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDVon EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Self-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!Von EverandSelf-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!Bewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsVon EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearVon EverandThe Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (23)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Von EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (110)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerVon EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (392)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityVon EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (3)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsVon EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (169)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryVon EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (44)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessVon EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (328)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsVon EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (3)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningVon EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (3)

- Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body's Most Underrated Organ (Revised Edition)Von EverandGut: The Inside Story of Our Body's Most Underrated Organ (Revised Edition)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (378)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceVon EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (51)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlVon EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (58)