Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Hugger v. Rutherford Institute, 4th Cir. (2003)

Hochgeladen von

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Hugger v. Rutherford Institute, 4th Cir. (2003)

Hochgeladen von

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

UNPUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

VICKIE C. HUGGER; CAROLYN SETTLE,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE; THE

RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE OF NORTH

CAROLINA, INCORPORATED; JOHN W.

WHITEHEAD; STEVEN H. ADEN,

Defendants-Appellees.

No. 02-1520

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of North Carolina, at Statesville.

Carl Horn, III, Chief Magistrate Judge.

(CA-00-180-5-H)

Argued: February 27, 2003

Decided: May 2, 2003

Before LUTTIG, WILLIAMS, and GREGORY, Circuit Judges.

Affirmed in part, reversed in part, and remanded by unpublished per

curiam opinion.

COUNSEL

ARGUED: John Michael Logsdon, MCELWEE LAW FIRM,

P.L.L.C., North Wilkesboro, North Carolina, for Appellants. Thomas

Stephen Neuberger, Wilmington, Delaware, for Appellees. ON

BRIEF: William H. McElwee, III, MCELWEE LAW FIRM,

P.L.L.C., North Wilkesboro, North Carolina, for Appellants.

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

Unpublished opinions are not binding precedent in this circuit. See

Local Rule 36(c).

OPINION

PER CURIAM:

Vickie C. Hugger and Carolyn Settle appeal from the district

courts denial of their motion to remand and its grant of summary

judgment for The Rutherford Institute (TRI), The Rutherford Institute

of North Carolina (TRINC),1 John W. Whitehead, individually, and

Steven H. Aden, individually, on Hugger and Settles claims of defamation, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and negligent

infliction of emotional distress. Because federal diversity jurisdiction

is proper between the parties, we affirm the district courts denial of

the motion to remand. Additionally, we affirm, on state law grounds,

the district courts grant of summary judgment on the intentional

infliction of emotional distress and negligent infliction of emotional

distress claims. Because the district court erred in reaching the constitutional issue of whether Hugger and Settle are required to meet the

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan actual malice standard before deciding the state law issue of whether sufficient evidence was proffered

to establish a claim of defamation, we reverse the district courts grant

of summary judgment on the defamation claim and remand for consideration of the state law issue in proceedings consistent with this

opinion.

I.

The claims in this case stem from two stories that H.D.,2 a twelveyear old student at C.B. Eller Elementary in Wilkes County, North

Carolina, told her mother about Settle, her sixth grade teacher, and

Hugger, her school principal. First, H.D. told her mother that Settle

1

Although the district court held that TRINC was a "sham" defendant,

TRINC has not been formally dismissed as a party.

2

Initials of minor child used pursuant to the Judicial Conference Policy

on Privacy and the E-Government Act of 2002.

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

ordered her to read the word "damn" in front of the class even though

H.D. explained that she does not say curse words for religious reasons. H.D. told her mother that when she refused, Settle sent her to

Principal Huggers office, who ordered H.D. to read the word "damn"

or receive in-house suspension for the rest of the day. At that point,

H.D. said, she returned to class and read the word in front of the class.

Second, H.D. told her mother that Settle made her erase "WWJD"3

and several crosses that she had drawn on the chalkboard in the "feature one student" section.

On November 8, 1999, H.D.s mother contacted The Rutherford

Institute (TRI) regarding H.D.s stories. TRI telephoned H.D.s

mother on November 10, 1999, to obtain more information and spoke

with H.D. who retold the stories and provided the name of the book

that the class was reading. TRI obtained a copy of the book and confirmed that it contained the word "damn." On November 15, 1999,

Whitehead, president of TRI, faxed a demand letter to the Superintendent of Wilkes County Schools and Hugger. The letter stated that

"Ms. Hugger and Ms. Settle have violated [H.D.]s First Amendment

rights of free speech and religious expression." (J.A. at 95.) The letter

demanded a written apology and indicated that if TRI did not receive

a response by the close of business the next day, it would "seek

redress for [H.D.] and her family in federal court." (J.A. at 97.)

Counsel for Wilkes County Schools immediately responded to

TRIs letter, saying that he was "in the process of ascertaining the

facts applicable to the incidents identified in [the] letter [and that] [a]n

appropriate response [would] be issued following completion of [the]

inquiry." (J.A. at 98.) On November 16, after counsel for Wilkes

County Schools spoke with TRIs legal coordinator and expressed his

concerns about the truthfulness of H.D.s stories, TRI contacted H.D.

again; she claimed that she had not lied and that the stories were true.

H.D. provided the name of a student in her class who could confirm

her story, but TRI was not able to get in touch with the student or the

students parents.

3

"WWJD" stands for "What Would Jesus Do" and is a popular admonition for Christians to consider how Jesus would act as a model for their

own actions.

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

On that same day, TRI issued a press release entitled "Sixth Grader

Punished for Refusing to Curse in Class." (J.A. at 99.) The press

release stated:

John W. Whitehead, president of The Rutherford Institute,

has intervened on behalf of [H.D.] and her mother . . ., with

the Wilkes County School Superintendent, Dr. Joseph Johnson. Twelve-year-old [H.D.], a student at C.B. Eller Elementary School in Elkin, North Carolina, was directed by

her teacher to read a portion of a book out loud in front of

her classmates. When [H.D.] skipped over the word "damn"

in the text and respectfully explained that she did so because

of her Christian beliefs, she was sent to the principals

office. The principal then ordered [H.D.] to say the swear

word or receive an in-house suspension for the remainder of

the day.

One week later, [H.D.] wrote "WWJD" ("What Would

Jesus Do") and drew some crosses on the blackboard as part

of the "feature one child" class participation program where

students express themselves on the class blackboard. When

her classmates left the room for lunch, however, [H.D.]s

teacher informed her that this type of information could not

be displayed on the blackboard and ordered her to remove

it.

The Rutherford Institute has demanded that a formal written apology be sent to [H.D.] and that informational copies

be sent to all district administrative and instructional personnel. In addition to the apology, The Rutherford Institute has

demanded that the teacher and the principal be given a written reprimand for the incident. . . . "[H.D.]s teacher and her

principal have violated not only [H.D.]s First Amendment

rights of free speech and religious expression, but also her

right not to be forced to go against her religious beliefs,"

said Steven H. Aden, Chief Litigation Counsel for The

Rutherford Institute. . . .

(J.A. at 99.)

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

On November 22, 1999, H.D. admitted that she had lied about the

stories. On November 23, TRI wrote a letter of apology to Hugger

and Settle and, on November 24, issued a press release entitled "Rutherford Institute Expresses Regret After Fraud is Disclosed; School

Girl Confesses To Fabricating A Claim Of Religious Discrimination."

(J.A. at 169.)

Hugger and Settle, both citizens of North Carolina, filed a complaint in state court alleging that the demand letter and the press

release were "false and impeached [them] in their character and their

profession." (J.A. at 12.) Hugger and Settle alleged that "defendants

had a duty . . . to make reasonable efforts to determine the truth or

falsity of the allegations[,] . . . failed to conduct a reasonable investigation of the allegations of [H.D.] prior to publishing false statements

to others," and acted "maliciously or with reckless disregard as to

whether the statements were false." (J.A. at 12.) Hugger and Settle

also alleged intentional infliction of emotional distress and negligent

infliction of emotional distress.

TRI, TRINC, Whitehead, and Aden removed the case to federal

court based on diversity of citizenship. Hugger and Settle moved to

remand the case, arguing that because TRINC is a North Carolina corporation, there was not complete diversity between the parties and

federal jurisdiction was not proper. Hugger and Settle also argued that

TRI should be deemed a citizen of North Carolina based on its relationship with TRINC, which would also destroy complete diversity.

The district court held that TRI is a citizen of Virginia and that

TRINC was a "sham" defendant under the doctrine of fraudulent joinder, and thus, despite TRINCs North Carolina citizenship, there was

complete diversity between the parties. The district court denied Hugger and Settles motion to reconsider its jurisdictional ruling based on

the citizenship of TRI.

TRI, TRINC, Whitehead, and Aden then moved for summary judgment on all three claims on the ground that the claims failed under

state law and on the ground that Hugger and Settle were public officials and had not shown the required actual malice. The district court

granted summary judgment to TRI, TRINC, Whitehead, and Aden on

the defamation claim on the ground that Hugger and Settle were public officials and had failed to present evidence of actual malice; the

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

district court granted summary judgment on the intentional and negligent infliction of emotional distress claims on the grounds that the

claims failed under state law and that Hugger and Settle had failed to

present evidence to support the existence of actual malice. Hugger

and Settle filed a timely notice of appeal of the denial of the motion

to remand and of the grant of summary judgment.

II.

We first address Hugger and Settles argument that the district

court erred by denying their motion to remand the case to the state

court. "[A]ny civil action brought in a State court of which the district

courts of the United States have original jurisdiction, may be removed

by the defendant or the defendants . . . ." 28 U.S.C.A. 1441(a) (West

1994). TRI, TRINC, Whitehead, and Aden based their removal on

diversity jurisdiction. The district courts have original jurisdiction

based on diversity over actions "where the matter in controversy

exceeds the sum or value of $75,000 . . . and is between . . . citizens

of different States." 28 U.S.C.A. 1332(a) (West 1993 & Supp.

2002). The requirement that the controversy be between "citizens of

different States" has been interpreted to require complete diversity

between the plaintiffs and defendants. In other words, "[t]o sustain

diversity jurisdiction there must exist an actual, substantial controversy between citizens of different states, all of whom on one side of

the controversy are citizens of different states from all parties on the

other side." City of Indianapolis v. Chase Natl Bank, 314 U.S. 63, 69

(1941) (internal citations omitted).

"The parties agree that the plaintiffs are citizens of North Carolina

and defendants Whitehead and Aden are citizens of Virginia. The parties also agree that TRI was incorporated in Virginia and TRINC was

incorporated in North Carolina." (Appellants Br. at 11-12.) For purposes of diversity jurisdiction, "a corporation shall be deemed to be

a citizen of any State by which it has been incorporated and of the

State where it has its principal place of business." 28 U.S.C.A.

1332(c)(1). The district court held that TRINCs North Carolina citizenship did not destroy complete diversity because TRINC was a

"sham" defendant under the doctrine of fraudulent joinder. See Wilson

v. Republic Iron & Steel Co., 257 U.S. 92, 97 (1921) (holding that the

"right of removal cannot be defeated by a fraudulent joinder of a resi-

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

dent defendant having no real connection with the controversy"). As

Hugger and Settle "acknowledge that there is no evidence that

[T]RINC independently performed any act or omission [that] would

create liability for tortious conduct," (J.A. at 61), we find no error in

the district courts holding that TRINC was a "sham" defendant that

does not defeat removal.

Hugger and Settle also argue that TRI should be deemed to be a

North Carolina citizen. The district court held that Hugger and Settles "contention that [T]RI is a North Carolina citizen by virtue of

reincorporation through [T]RINC and [T]RINCs alleged consolidation into [T]RI is manifestly contradicted by the undisputed facts."

(J.A. at 65 n.1.) We review the finding that TRI is not a citizen of

North Carolina for clear error. Sligh v. Doe, 596 F.2d 1169, 1171 (4th

Cir. 1979) ("Citizenship . . . presents a preliminary question of fact

to be determined by the trial court. Appellate review should be limited

by the usual standards applicable to such determinations."). TRI is

incorporated in Virginia, and is thus a citizen of Virginia. No evidence suggests, and neither party contends, that TRI was formally

incorporated in North Carolina or has its principal place of business

there. Hugger and Settle make two arguments why TRI should nevertheless be deemed a citizen of North Carolina.

First, they argue that TRINC was consolidated into TRI and that

this consolidation gives TRI citizenship in North Carolina. They rely

on Town of Bethel v. Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company, 81 F.2d

60 (4th Cir. 1936), for the proposition that a consolidation results in

the consolidated company being a citizen of each state in which its

constituent corporations existed.

In Town of Bethel, we considered whether the Atlantic Coast Line

Railroad Company (ACL) was a citizen of North Carolina for diversity purposes. Id. ACL was formed pursuant to a complicated "agreement of consolidation or merger," id. at 62, between many railroad

companies in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, including

two that were relevant to our decision, the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company of Virginia (ACLVA), a corporation created under the

laws of Virginia and North Carolina, and the Wilmington & Weldon

Railroad Company, a corporation created under the laws of North

Carolina. The North Carolina enabling act, which authorized the Wil-

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

mington & Weldon Railroad Company to consolidate with other companies, provided that "any and all corporations consolidated, leased or

organized under the provisions of this act shall be domestic corporations of North Carolina." Id. at 62. The agreement provided that all

of the companies would be consolidated into ACLVA, and then

ACLVA would change its name to ACL.

ACL argued that it was not a North Carolina citizen because what

the agreement provided for was actually a merger whereby only the

Virginia corporation remained. Our holding, however, did not turn on

the distinction between mergers and consolidations. We held that

ACL was a North Carolina corporation because ACLVA "the immediate predecessor of [ACL], was already a corporation of both states

when the consolidation . . . took place and the [North Carolina]

enabling acts [regarding Wilmington & Weldon] expressly provided

that it should continue to be a domestic corporation after the railroad

properties should have been united." Id. at 65.

In contrast, TRI, which would be the "immediate predecessor" in

the alleged consolidation in this case, was not a North Carolina corporation prior to the alleged consolidation and there is no indication that

the North Carolina legislature passed an enabling act requiring that a

consolidation between TRINC and another corporation would result

in a North Carolina corporation. Accordingly, Town of Bethel does

not support Hugger and Settles argument that TRI should be deemed

a North Carolina citizen.

Even assuming, arguendo, that a "consolidation" results in the consolidated corporation being a citizen of each state in which its constituent corporations existed, there was no "consolidation" in this case.4

4

As noted in the text, we assume without deciding that where a state

legislature passes an enabling act authorizing a corporation organized in

that state to execute articles of consolidation with a corporation organized outside of that state, the "new consolidated company has a legal

existence in each of the states in which the constituent companies previously existed," Winn v. Wabash R. Co., 118 F. 55, 58 (C.C.W.D. Mo.

1902) (cited in Town of Bethel, 81 F.2d at 68). We find no support in our

case law, however, for the proposition that something less than a formal

consolidation authorized by legislative acts of the various states results

in a corporation that is a citizen in each state in which its constituent corporations existed.

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

Hugger and Settle base their argument that there was a consolidation

solely on the affidavit of one of the directors of TRI, who stated that

"[i]n 1992, TRI reorganized into regional offices operated by TRI."

(J.A. at 30.) According to Blacks Law Dictionary, a consolidation of

corporations "[o]ccurs when two or more corporations are extinguished, and by the same process a new one is created." Blacks Law

Dictionary 309 (6th ed. 1990). Hugger and Settle concede that TRINC

"has not been administratively dissolved and has not filed articles of

dissolution." (Appellants Br. at 13.) Moreover, there is no evidence

that TRI was extinguished pursuant to its reorganization. Thus, the

district courts finding that TRI is not a North Carolina citizen by virtue of "consolidation" with TRINC is not clearly erroneous.

Second, Hugger and Settle argue that "TRINC is merely a reincorporation of TRI in North Carolina." (Appellants Br. at 18.) TRINC

is a separate corporation that was incorporated and directed by North

Carolina residents, not by TRI. Again, the district courts finding that

there are no facts to support a formal reincorporation is not clearly

erroneous.

Accordingly, we affirm the district courts denial of the motion to

remand as the requisite diversity existed between the parties.

III.

We now consider Hugger and Settles argument that the district

court erred in granting summary judgment to TRI, TRINC, Whitehead, and Aden (hereinafter, collectively, TRI) on their intentional

and negligent infliction of emotional distress claims. The district court

held that there were no affidavits or other evidence to support Hugger

and Settles "bare allegations," (J.A. at 81(a)), of an essential element

of both intentional and negligent infliction of emotional distress under

state law, namely severe emotional distress, and thus, granted summary judgment to TRI.5 "Summary judgment is appropriate when a

5

The district court also held that TRI was entitled to summary judgment on the intentional and negligent infliction of emotional distress

claims on the ground that Hugger and Settle, as "public officials," were

required to prove actual malice under Hustler Magazine v. Falwell, 485

10

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

party, who would bear the burden on the issue at trial, does not forecast evidence sufficient to establish an essential element of the case,

such that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and the

moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law." Wells v.

Liddy, 186 F.3d 505, 520 (4th Cir. 1999) (internal citation omitted)

(quoting Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(c)). "Viewing the facts in the light most

favorable to the non-moving party, we review a grant of summary

judgment de novo." Id.

Under North Carolina law, to recover for intentional infliction of

emotional distress, "a plaintiff must prove (1) extreme and outrageous conduct, (2) which is intended to cause and does cause (3)

severe emotional distress to another." Beck v. City of Durham, 573

S.E.2d 183, 190-91 (N.C. App. 2002) (quoting Dickens v. Puryear,

276 S.E.2d 325, 335 (N.C. 1981)). An action for negligent infliction

of emotional distress under North Carolina law "has three elements:

(1) defendant engaged in negligent conduct; (2) it was reasonably

foreseeable that such conduct would cause the plaintiff severe emotional distress and (3) defendants conduct, in fact, caused severe

emotional distress." Wells v. N.C. Dept of Corr., 567 S.E.2d 803,

814 (N.C. App. 2002) (quoting Robblee v. Budd Servs., Inc., 525

S.E.2d 847, 849 (N.C. App. 2000)).

Hugger and Settle argue that their medical records show that they

suffer from "severe emotional distress" because they both suffer from

depression. "[T]he term severe emotional distress [for purposes of

both intentional and negligent infliction of emotional distress claims]

means any emotional or mental disorder, such as, for example, neurosis, psychosis, chronic depression, phobia, or any other type of severe

and disabling emotional or mental condition which may be generally

recognized and diagnosed by professionals trained to do so." Waddle

v. Sparks, 414 S.E.2d 22, 27 (N.C. 1992) (emphasis in original) (quotU.S. 46, 56 (1988), which applied the New York Times Co. actual malice

requirement to claims for emotional distress. As our resolution of the

state law issue is dispositive of the intentional and negligent infliction of

emotional distress claims, we need not and do not reach this constitutional question in affirming the district courts grant of summary judgment.

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

11

ing Johnson v. Ruark Obstetrics and Gynecology Assocs., 395 S.E.2d

85, 97 (N.C. 1990)). As the Supreme Court of North Carolina

explained,

"It is only where [emotional distress] is extreme that the liability arises. Complete emotional tranquility is seldom

attainable in this world, and some degree of transient and

trivial emotional distress is a part of the price of living

among people. The law intervenes only where the distress

inflicted is so severe that no reasonable man could be

expected to endure it. The intensity and the duration of the

distress are factors to be considered in determining its severity."

Id. (emphasis in original) (quoting Restatement (Second) of Torts

46 cmt. j (1965)). Viewing the facts in the light most favorable to

Hugger and Settle, the evidence does not show that they suffer from

any emotional distress "so severe that no reasonable man could be

expected to endure it," id. (emphasis deleted). At most, the medical

reports show that Settle had "worsening anxiety" on November 29,

1999, (J.A. at 128), and that Hugger received "routine medication

management of depression," (J.A. at 148.). These conditions do not

rise to the level of severe emotional distress under North Carolina

law. See Waddle, 414 S.E.2d at 27. Moreover, with regard to Hugger,

she also did not forecast sufficient evidence to establish that her

depression was caused by TRIs actions. Her medical treatment was

not closely connected temporally with TRIs actions, and her medical

records indicate that her depression was caused by events in her childhood. Accordingly, we affirm the district courts grant of summary

judgment on the intentional and negligent infliction of emotional distress claims.

IV.

Finally, we turn to Hugger and Settles arguments that the district

court erred by granting summary judgment on their defamation claim

based on a finding that they were public officials required to prove

actual malice to recover damages for defamation and that they failed

to prove actual malice. A defamation claim is, at its root, a state law

tort claim. The First Amendment, incorporated and applied to the

12

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

states through the Fourteenth Amendment, however, limits the state

remedies available to a defamation plaintiff. New York Times Co. v.

Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964). Under New York Times Co., a plaintiff

who is a "public official" may not recover damages for defamation

"relating to his official conduct unless he proves that the statement

was made with actual malicethat is, with knowledge that it was

false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not." Id. at

279-80.

TRI moved for summary judgment on the grounds that Hugger and

Settle were public officials who had not shown actual malice and that

the underlying statements were not defamatory. The district court proceeded directly to the constitutional question of whether Hugger and

Settle are public officials, without addressing the state law question

of whether Hugger and Settle proffered sufficient evidence to establish a claim of defamation under North Carolina law.

"[C]ourts should avoid deciding constitutional questions unless

they are essential to the disposition of a case." Bell Atl. Md., Inc. v.

Prince Georges County, Md., 212 F.3d 863, 865 (4th Cir. 2000)

(applying the rule of Ashwander v. Tenn. Valley Auth., 297 U.S. 288,

341-47 (1936) (Brandeis, J., concurring)); cf. Hutchinson v. Proxmire,

443 U.S. 111, 121 (1979).6 "[B]y deciding the constitutional question

6

In Hutchinson v. Proxmire, 443 U.S. 111, 122 (1979), the Court recognized that its practice is "to avoid reaching constitutional questions if

a dispositive nonconstitutional ground is available." Hutchinson, 443

U.S. at 122. In Hutchinson, the court of appeals addressed the constitutional issue of whether the plaintiff was a public figure without addressing the state law issue of whether the statements constituted defamation

under state law. Id. at 121-22. The Court noted that ordinarily it would

remand the case for resolution of the state law issue because resolution

of the state law issue might render resolution of the First Amendment

issue unnecessary. Id. at 122. The court of appeals observation that the

statements "may be defamatory falsehoods," in explaining its conclusion

that the statements were protected by the Speech and Debate Clause,

however, indicated that the court of appeals would have held that the

statements at issue constituted defamation under state law. Id. at 123.

The Court interpreted this observation to indicate the court of appeals

view that "the appeal could not be decided without reaching the constitu-

HUGGER v. THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE

13

. . . in advance of considering the state law question[ ] upon which the

case might have been disposed of, the district court committed reversible error." Bell Atl. Md., 212 F.3d at 866. Accordingly, we reverse

the district courts grant of summary judgment on Hugger and Settles

defamation claim and remand for consideration of the state law issue

in proceedings consistent with this opinion. We express no opinion on

the proper resolution of either the state law issue or the constitutional

law issue.

V.

For the foregoing reasons, we affirm the district courts denial of

the motion to remand and the grant of summary judgment to TRI on

the intentional and negligent infliction of emotional distress claims,

and we reverse the grant of summary judgment to TRI on the defamation claim and remand for consideration of the state law issue in proceedings consistent with this opinion.

AFFIRMED IN PART, REVERSED IN PART, AND REMANDED

tional question." Id. (internal quotation marks omitted). Thus, the Court

held that it was necessary to reach the constitutional issue as well. Id.

In the instant case, there is no indication that the district court would

consider the statements to constitute defamation under state law. In fact,

the district court refers to the statements as "the allegedly defamatory

publication." (J.A. at 80.) Accordingly, we follow what the Hutchinson

Court indicated would be the ordinary remedy when the lower court

reaches a constitutional issue without addressing a potentially dispositive

state law issue and remand to the district court for consideration of the

state law issue.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument9 SeitenUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument7 SeitenCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument20 SeitenUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument2 SeitenGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument21 SeitenCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument8 SeitenPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument4 SeitenUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument6 SeitenBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokument24 SeitenPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument15 SeitenApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument22 SeitenConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument50 SeitenUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument25 SeitenPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument5 SeitenWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument100 SeitenHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument25 SeitenUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokument10 SeitenPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokument14 SeitenPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument27 SeitenUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument5 SeitenUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument25 SeitenUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDokument17 SeitenPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument9 SeitenNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument18 SeitenWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument10 SeitenNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument15 SeitenUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument2 SeitenUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument4 SeitenUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument7 SeitenUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Dokument5 SeitenPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Preferensi Konsumen &strategi Pemasaran Produk Bayem Organik Di CVDokument8 SeitenPreferensi Konsumen &strategi Pemasaran Produk Bayem Organik Di CVsendang mNoch keine Bewertungen

- Genset Ops Manual 69ug15 PDFDokument51 SeitenGenset Ops Manual 69ug15 PDFAnonymous NYymdHgy100% (1)

- 2005-05-12Dokument18 Seiten2005-05-12The University Daily KansanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isolation and Characterization of Galactomannan From Sugar PalmDokument4 SeitenIsolation and Characterization of Galactomannan From Sugar PalmRafaél Berroya Navárro100% (1)

- App 17 Venmyn Rand Summary PDFDokument43 SeitenApp 17 Venmyn Rand Summary PDF2fercepolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Experiment Report Basic Physics "Total Internal Reflection"Dokument10 SeitenExperiment Report Basic Physics "Total Internal Reflection"dita wulanNoch keine Bewertungen

- QUICK CLOSING VALVE INSTALLATION GUIDEDokument22 SeitenQUICK CLOSING VALVE INSTALLATION GUIDEAravindNoch keine Bewertungen

- Afforestation in Arid and Semi Arid RegionsDokument68 SeitenAfforestation in Arid and Semi Arid RegionsMilian Marian SanduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chemicals Zetag DATA Powder Magnafloc 351 - 0410Dokument2 SeitenChemicals Zetag DATA Powder Magnafloc 351 - 0410PromagEnviro.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accuracy of Real-Time Shear Wave Elastography in SDokument10 SeitenAccuracy of Real-Time Shear Wave Elastography in SApotik ApotekNoch keine Bewertungen

- ZP Series Silicon Rectifier: Standard Recovery DiodesDokument1 SeiteZP Series Silicon Rectifier: Standard Recovery DiodesJocemar ParizziNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edna Adan University ThesisDokument29 SeitenEdna Adan University ThesisAbdi KhadarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fischer FBN II BoltDokument5 SeitenFischer FBN II BoltJaga NathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Balloons FullDokument19 SeitenBalloons FullHoan Doan NgocNoch keine Bewertungen

- EXPERIMENT 5 - Chroamtorgraphy GRP9 RevDokument2 SeitenEXPERIMENT 5 - Chroamtorgraphy GRP9 RevMic100% (2)

- D Formation Damage StimCADE FDADokument30 SeitenD Formation Damage StimCADE FDAEmmanuel EkwohNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ielts Band Score 7Dokument2 SeitenIelts Band Score 7Subhan Iain IINoch keine Bewertungen

- CV Dang Hoang Du - 2021Dokument7 SeitenCV Dang Hoang Du - 2021Tran Khanh VuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bandong 3is Q4M6Dokument6 SeitenBandong 3is Q4M6Kento RyuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joyforce SDS - PVA Pellet - r2.ENDokument3 SeitenJoyforce SDS - PVA Pellet - r2.ENjituniNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSE 2103 - Lec 12 (7 Files Merged)Dokument118 SeitenMSE 2103 - Lec 12 (7 Files Merged)md akibhossainNoch keine Bewertungen

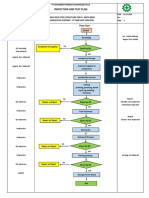

- Inspection and Test Plan: Flow Chart Start IncomingDokument1 SeiteInspection and Test Plan: Flow Chart Start IncomingSinden AyuNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pentester BlueprintDokument27 SeitenThe Pentester Blueprintjames smith100% (1)

- Arecaceae or Palmaceae (Palm Family) : Reported By: Kerlyn Kaye I. AsuncionDokument23 SeitenArecaceae or Palmaceae (Palm Family) : Reported By: Kerlyn Kaye I. AsuncionNamae BacalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Somali Guideline of InvestorsDokument9 SeitenSomali Guideline of InvestorsABDULLAHI HAGAR FARAH HERSI STUDENTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Siemens SIVACON S8, IEC 61439 Switchgear and Control PanelDokument43 SeitenSiemens SIVACON S8, IEC 61439 Switchgear and Control PanelGyanesh Bhujade100% (2)

- Radiol 2020201473Dokument37 SeitenRadiol 2020201473M Victoria SalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conder Separator Brochure NewDokument8 SeitenConder Separator Brochure Newednavilod100% (1)

- Regulation of Body FluidsDokument7 SeitenRegulation of Body FluidsRuth FamillaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ulcus Decubitus PDFDokument9 SeitenUlcus Decubitus PDFIrvan FathurohmanNoch keine Bewertungen