Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Ravago To Panis Full Cases Labor

Hochgeladen von

joan dlcOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Ravago To Panis Full Cases Labor

Hochgeladen von

joan dlcCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 1

(Ravago to Panis Full Cases)

1. Ravago vs Esso

G.R. No. 158324. March 14, 2005

ROBERTO RAVAGO, Petitioners,

vs.

ESSO EASTERN MARINE, LTD. and TRANS-GLOBAL MARITIME AGENCY,

INC., Respondents.

DECISION

CALLEJO, SR., J.:

Before us is a petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 of the 1997

Rules of Court, as amended, of the Decision 1 of the Court of Appeals (CA) as

well as its Resolution in CA-G.R. SP No. 66234 which denied the motion for

reconsideration thereof.

The Factual Antecedents

The Esso Eastern Marine Ltd. (EEM), now the Petroleum Shipping Ltd., is a

foreign company based in Singapore and engaged in maritime commerce. It

is represented in the Philippines by its manning agent and co-respondent

Trans-Global Maritime Agency, Inc. (Trans-Global), a corporation organized

under the Philippine laws.

Roberto Ravago was hired by Trans-Global to work as a seaman on board

various Esso vessels. On February 13, 1970, Ravago commenced his duty as

S/N wiper on board the Esso Bataan under a contract that lasted until

February 10, 1971. Thereafter, he was assigned to work in different Esso

vessels where he was designated diverse tasks, such as oiler, then assistant

engineer. He was employed under a total of 34 separate and unconnected

contracts, each for a fixed period, by three different companies, namely,

Esso Tankers, Inc. (ETI), EEM and Esso International Shipping (Bahamas) Co.,

Ltd. (EIS), Singapore Branch. Ravago worked with Esso vessels until August

22, 1992, a period spanning more than 22 years, thus:

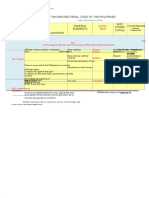

CONTRACT FROM DURATION TO

POSITION

VESSEL

COMPANY

13 Feb 70

10 Feb 71

SN/Wiper

Esso Bataan

ETI2

07 May 71

27 May 72

Wiper

Esso Yokohama

EEM3

07 Aug 72

02 Jul 73

Oiler

Esso Kure

EEM

03 Oct 73

30 Jun 74

Oiler

Esso Bangkok

ETI

18 Sep 74

26 July 75

Oiler

Esso Yokohama

EEM

23 Oct 75

22 Jun 76

Oiler

Esso

Dickson

10 Sep 76

26 Dec 76

Oiler

Esso Bangkok

ETI

27 Dec 76

29 Apr 77

Temporary

3AE

Jr. Esso Bangkok

ETI

08 Jul 77

15 Mar 78

Jr. 3AE

Esso Bombay

ETI

03 Jun 78

03 Feb 79

Temporary 3AE

Esso Hongkong

ETI

Port EEM

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 2

04 Apr 79

24 Jun 79

3AE

Esso Orient

EEM

25 Jun 79

16 Jul 79

3AE

Esso Yokohama

EEM

17 Jul 79

05 Dec 79

3AE

Esso Orient

EEM

10 Feb 80

25 Oct 80

3AE

Esso Orient

EEM

19 Jan 81

03 Jun 81

3AE

Esso

Dickson

04 Jun 81

11 Sep 81

3AE

Esso Orient

EEM

06 Dec 81

20 Apr 82

3AE

Esso Chawan

EEM

21 Apr 82

01 Aug 82

Temporary 2AE

Esso Chawan

EEM*

03 Nov 82

06 Feb 83

2AE

Esso Jurong

EEM

07 Feb 83

10 Jul 83

2AE

Esso Yokohama

EEM

31 Aug 83

13 Mar 84

2AE

Esso Tumasik

EEM

04 May 84

08 Jan 85

2AE

Esso

Dickson

13 Mar 85

31 Oct 85

2AE

Esso Castellon

EEM

29 Dec 85

22 Jul 86

2AE

Esso Jurong

EIS4

13 Sep 86

09 Jan 87

2AE

Esso Orient

EIS

21 Mar 87

15 Oct 87

2AE

Esso

Dickson

20 Nov 87

18

Dec

Temporary

19 Dec 87

25 Jun 88

2AE

Esso Melbourne EIS

04 Aug 88

19 Mar 89

Temporary 1AE

Esso

Dickson

Port EIS

20 Mar 89

19 May 89

1AE

Esso

Dickson

Port EIS*

28 Jul 89

17 Feb 90

1AE

Esso Melbourne EIS

16 Apr 90

11 Dec 90

1AE

Esso Orient

09 Feb 91

06 Oct 91

1AE

Esso Melbourne EIS

16 Dec 91

22 Aug 92

1AE

Esso Orient

87 1AE

Esso Chawan

Port EEM

Port EEM

Port EIS

EIS

EIS

EI

* Upgraded/Confirmed on regular rank on board.5

On August 24, 1992, or shortly after completing his latest contract with EIS,

Ravago was granted a vacation leave with pay from August 23, 1992 until

October 28, 1992. Preparatory to his embarkation under a new contract, he

was ordered to report, on September 28, 1992, for a Medical Pre-

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 3

Employment Examination.6 The Pre-Employment Physical Examination

Record shows that Ravago passed the medical examination conducted by the

O.P. Jacinto Medical Clinic, Inc. on October 6, 1992. 7 He, likewise, attended a

Pre-Departure Orientation Seminar conducted by the Capt. I.P. Estaniel

Training Center, a division of Trans-Global, on October 7, 1992.8

On the night of October 12, 1992, a stray bullet hit Ravago on the left leg

while he was waiting for a bus ride in Cubao, Quezon City. He fractured his

left proximal tibia and was hospitalized at the Philippine Orthopedic Hospital.

Ravagos wife, Lolita, informed Trans-Global and EIS of the incident on

October 13, 1992 for purposes of availing medical benefits. As a result of his

injury, Ravagos doctor opined that he would not be able to cope with the job

of a seaman and suggested that he be given a desk job. 9 Ravagos left leg

had become apparently shorter, making him walk with a limp. For this

reason, the company physician, Dr. Virginia G. Manzo, found him to have lost

his dexterity, making him unfit to work once again as a seaman. 10 Citing the

opinion of Ravagos doctor, Dr. Manzo wrote:

Because of his unsteady gait, pronounced limp, and loss of normal

dexterity of his leg and foot, we doubted whether Mr. Ravago can physically

tackle the usual activities of a seaman in the course of his work without any

added risk over and above the ordinary or standard risk inherent to his job.

These activities include climbing up and down the engine room through a

long flight of iron stairs with narrow steps which could be slippery at times

due to grease or oil, jumping from an unsteady and floating motor launch or

boat to board or alight a tanker through a flight of steps or climbing up and

down a pilot ladder, wearing of heavy safety shoes, etc.

Mr. Ravagos doctor replied that, after being informed about the nature of the

job, he believes that Mr. Ravago would not be able to cope with these kinds

of activities. In effect, the Orthopedic doctor said Mr. Ravago is not fit to go

back to his work as a seaman.

We concur with the opinion of the doctor that Mr. Ravago is not fit to go back

to his job as a seaman in view of the risk of physical injury to himself as

result of the deformity and loss of dexterity of his injured leg.

As a seaman, we consider his inability partial permanent. His injury

corresponds to Grade 13 in the Schedule of Disability of the Standard

Employment Contract. 11

Consequently, instead of rehiring Ravago, EIS paid him his Career

Employment Incentive Plan (CEIP)12 as of March 1, 1993 and his final tax

refund for 1992. After deducting his Social Security System and medical

contributions from November 1992 to February 1993, EIS remitted the net

amount of P162,232.65, following Ravagos execution of a Deed of Quitclaim

and/or Release.13

However, on March 22, 1993, Ravago filed a complaint 14 for illegal dismissal

with prayer for reinstatement, backwages, damages and attorneys fees

against Trans-Global and EIS with the Philippine Overseas Employment

Administration Adjudication Office.

In their Answer dated April 14, 1993, respondents denied that Ravago was

dismissed without notice and just cause. Rather, his services were no longer

engaged in view of the disability he suffered which rendered him unfit to

work as a seafarer. This fact was further validated by the company doctor

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 4

and Ravagos attending physician. They averred that Ravago was a

contractual employee and was hired under 34 separate contracts by different

companies.

In his position paper, Ravago insisted that he was fit to resume pre-injury

activities as evidenced by the certification 15 issued by Dr. Marciano Foronda

M.D., one of his attending physicians at the Philippine Orthopedic Hospital,

that "at present, fracture of tibia has completely healed and patient is fit to

resume pre-injury activities anytime."16 Ravago, likewise, asserted that he

was not a mere contractual employee because the respondents regularly and

continuously rehired him for 23 years and, for his continuous service, was

awarded a CEIP payment upon his termination from employment.

On December 15, 1996, Labor Arbiter Ramon Valentin C. Reyes rendered a

decision in favor of Ravago, the complainant. He ruled that Ravago was a

regular employee because he was engaged to perform activities which were

usually necessary or desirable in the usual trade or business of the employer.

The Labor Arbiter noted that Ravagos services were repeatedly contracted;

he was even given several promotions and was paid a monthly service

experience bonus. This was in keeping with the increasing number of long

term careers established with the respondents. Finally, the Labor Arbiter

resolved that an employer cannot terminate a workers employment on the

ground of disease unless there is a certification by a competent public health

authority that the said disease is of such nature or at such a stage that it

cannot be cured within a period of six months even with proper medical

treatment. He concluded that Ravago was illegally dismissed. The decretal

portion of the Labor Arbiters decision reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, judgment is hereby rendered finding the

dismissal illegal and ordering respondents to reinstate complainant to his

former position without loss of seniority rights and other benefits. Further,

the respondents are jointly and severally liable to pay complainant

backwages from the time of his dismissal up to the promulgation of this

decision. Such backwages is provisionally fixed at US$96,285.00 less the

P162,285.83 (sic) paid to the complainant as Career Employment Incentive

Plan. And ordering respondents to pay complainant 10% of the total

monetary award as attorneys fees.

All other claims are dismissed for lack of merit.

SO ORDERED.17

Aggrieved, the respondents appealed the decision to the National Labor

Relations Commission (NLRC) on July 3, 1997, raising the following grounds:

THE DECISION IS VITIATED BY SERIOUS ERRORS IN THE FINDINGS OF FACT

WHICH, IF NOT CORRECTED, WOULD CAUSE GRAVE OR IRREPARABLE

DAMAGE OR INJURY TO THE RESPONDENTS. THESE FINDINGS ARE:

(A) THAT COMPLAINANT WAS A REGULAR EMPLOYEE BECAUSE HE WAS HIRED

AND REHIRED IN VARIOUS CAPACITIES ON BOARD ESSO VESSELS IN A SPAN

OF 23 YEARS;

(B) THAT COMPLAINANT WAS A REGULAR EMPLOYEE BECAUSE HE WAS

ENGAGED IN THE SERVICES INDISPENSABLE IN THE OPERATION OF THE

VARIOUS VESSELS OF RESPONDENTS;

(C) THAT COMPLAINANT WAS FIT TO RESUME PRE-INJURY ACTIVITIES AND HIS

FRACTURE COMPLETELY HEALED NOTWITHSTANDING A CONTRARY MEDICAL

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 5

OPINION OF COMPLAINANTS OWN PHYSICIAN AND RESPONDENTS COMPANY

PHYSICIAN; AND

(D) THAT COMPLAINANT WAS ILLEGALLY DISMISSED BY RESPONDENTS. 18

On April 26, 2001, the NLRC rendered a decision affirming that of the Labor

Arbiter. The NLRC based its decision in the case of Millares v. National Labor

Relations Commission,19 wherein it was held that:

It is, likewise, clear that petitioners had been in the employ of the private

respondents for 20 years. The records reveal that petitioners were

repeatedly re-hired by private respondents even after the expiration of their

respective eight-month contracts. Such repeated re-hiring which continued

for 20 years, cannot but be appreciated as sufficient evidence of the

necessity and indispensability of petitioners service to the private

respondents business or trade.

Verily, as petitioners had rendered 20 years of service, performing activities

which were necessary and desirable in the business or trade of private

respondents, they are, by express provision of Article 280 of the Labor Code,

considered regular employees.20

The NLRC, likewise, declared that Ravago was illegally dismissed and that

the quitclaim executed by him could not be considered as a waiver of his

right to question the validity of his dismissal and seek reinstatement and

other reliefs. According to the NLRC, such quitclaim is against public policy,

considering the economic disadvantage of the employee and the inevitable

pressure brought about by financial capacity.

The respondents filed a motion for reconsideration of the decision, claiming

that the ruling of the Court in Millares v. NLRC21 had not yet become final and

executory. However, the NLRC denied the motion.

Thereafter, the respondents filed a petition for certiorari before the CA on the

following grounds: (a) the ruling in Millares v. NLRC had not yet acquired

finality, nor has it become a law of the case or stare decisis because the

Court was still resolving the pending motion for reconsideration; (b) Ravago

was not illegally dismissed because after the expiration of his contract, there

was no obligation on the part of the respondents to rehire him; and (c) the

quitclaim signed by Ravago was voluntarily entered into and represented a

reasonable settlement of the account due him.

On August 29, 2001, the respondents filed an Urgent Application for the

Issuance of a Temporary Restraining Order and Writ of Preliminary Injunction

to enjoin and restrain the Labor Arbiter from enforcing his decision. On

September 5, 2001, the CA issued a Resolution 22 temporarily restraining

NLRC Sheriff Manolito Manuel from enforcing and/or implementing the

decision of the Labor Arbiter as affirmed by the NLRC.

On November 14, 2001, the CA granted the application for preliminary

injunction upon filing by the respondents of a bond in the amount of

P500,000.00. Thus, the respondents filed the surety bond as directed by the

appellate court. Before the approval thereof, however, Ravago filed a motion

to set aside the Resolution dated November 14, 2001, principally arguing

that the instant case was a labor dispute, wherein an injunction is proscribed

under Article 25423 of the Labor Code of the Philippines.

In their comment on Ravagos motion, the respondents professed that the

case before the CA did not involve a labor dispute within the meaning of

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 6

Article 212(l)24 of the Labor Code of the Philippines, but a money claim

against the employer as a result of termination of employment.

On August 28, 2002, the CA rendered a decision in favor the respondents.

The fallo of the decision reads:

WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED. The assailed decisions of the NLRC

are hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE and the injunctive writ issued on

November 14, 2001, is hereby made PERMANENT.

SO ORDERED.25

The CA ratiocinated as follows:

The employment, deployment, rights and obligation of Filipino seafarers are

particularly set forth under the rules and regulations governing overseas

employment promulgated by the POEA. Section C, Part I of the Standard

Employment Contract Governing the Employment of All Filipino Seamen on

Board Ocean-Going Vessels emphatically provides the following:

"SECTION C. DURATION OF CONTRACT

The period of employment shall be for a fix ( sic) period but in no case to

exceed 12 months and shall be stated in the Crew Contract. Any extension of

the Contract period shall be subject to the mutual consent of the parties."

It is clear from the foregoing that seafarers are contractual employees whose

terms of employment are fixed for a certain period of time. A fixed term is an

essential and natural appurtenance of seamens employment contracts to

which, whatever the nature of the engagement, the concept of regular

employment under Article 280 of the Labor Code does not find application.

The contract entered into by a seafarer with his employer sets in detail the

nature of his job, the amount of his wage and, foremost, the duration of his

employment. Only a satisfactory showing that both parties dealt with each

other on more or less equal terms with no dominance exercised by the

employer over the seafarer is necessary to sustain the validity of the

employment contract. In the absence of duress, as it is in this case, the

contract constitutes the law between the parties.26

The CA noted that the employment status of seafarers has been established

with finality by the Courts reconsideration of its decision in Millares v.

National Labor Relations Commission,27 wherein it was ruled that seamen are

contractual employees. According to the CA, the fact that Ravago was not

rehired upon the completion of his contract did not result in his illegal

dismissal; hence, he was not entitled to reinstatement or payment of

separation pay. The CA, likewise, affirmed the writ of preliminary injunction it

earlier issued, declaring that an injunction is a preservative remedy issued

for the protection of a substantive right or interest, an antidote resorted to

only when there is a pressing necessity to avoid injurious consequences

which cannot be rendered under any standard compensation.

Hence, the present recourse.

Ravago, now the petitioner, has raised the following issues:

I.

[WHETHER OR NOT] THE COURT OF APPLEALS GRAVELY ERRED AND

VIOLATED THE LABOR CODE WHEN IT ISSUED A RESTRAINING ORDER AND

THEREAFTER A WRIT OF PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION IN CA-G.R. SP NO. 66234.

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 7

II.

[WHETHER OR NOT] THE COURT OF APPEALS GRAVELY ERRED, [AND]

BLATANTLY DISREGARDED THE CONSTITUTIONAL MANDATE ON PROTECTION

TO FILIPINO OVERSEAS WORKERS, AND COUNTENANCED UNWARRANTED

DISCRIMINATION WHEN IT RULED THAT PETITIONER CANNOT BECOME A

REGULAR EMPLOYEE.28

On the first issue, the petitioner asserts that the CA violated Article 254 of

the Labor Code when it issued a temporary restraining order, and thereafter

a writ of preliminary injunction, to derail the enforcement of the final and

executory judgment of the Labor Arbiter as affirmed by the NLRC. On the

other hand, the respondents contend that the issue has become academic

since the CA had already decided the case on its merits.

The contention of the petitioner does not persuade.

The petitioners reliance on Article 254 29 of the Labor Code is misplaced. The

law proscribes the issuance of injunctive relief only in those cases involving

or growing out of a labor dispute. The case before the NLRC neither involves

nor grows out of a labor dispute. It did not involve the fixing of terms or

conditions of employment or representation of persons with respect thereto.

In fact, the petitioners complaint revolves around the issue of his alleged

dismissal from service and his claim for backwages, damages and attorneys

fees. Moreover, Article 254 of the Labor Code specifically provides that the

NLRC may grant injunctive relief under Article 218 thereof.

Besides, the anti-injunction policy of the Labor Code, basically, is freedom at

the workplace. It is more appropriate in the promotion of the primacy of free

collective bargaining and negotiations, including voluntary arbitration,

mediation and conciliation, as modes of settling labor and industrial

disputes.30

Generally, an injunction is a preservative remedy for the protection of a

persons substantive rights or interests. It is not a cause of action in itself but

a mere provisional remedy, an appendage to the main suit. Pressing

necessity requires that it should be resorted to only to avoid injurious

consequences which cannot be remedied under any measure of

consideration. The application of an injunctive writ rests upon the presence

of an exigency or of an exceptional reason before the main case can be

regularly heard. The indispensable conditions for granting such temporary

injunctive relief are: (a) that the complaint alleges facts which appear to be

satisfactory to establish a proper basis for injunction, and (b) that on the

entire showing from the contending parties, the injunction is reasonably

necessary to protect the legal rights of the plaintiff pending the litigation.31

It bears stressing that in the present case, the respondents petition contains

facts sufficient to warrant the issuance of an injunction under Article 218,

paragraph (e) of the Labor Code of the Philippines. 32 Further, respondents

had already posted a surety bond more than adequate to cover the judgment

award.

On the second issue, the petitioner earnestly urges this Court to re-examine

its Resolution dated July 29, 2002 in Millares v. National Labor Relations

Commission33 and reinstate the doctrine laid down in its original decision

rendered on March 14, 2000, wherein it was initially determined that a

seafarer is a regular employee. The petitioner asserts that the decision of the

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 8

CA and, indirectly, that of the Resolution of this Court dated July 29, 2002,

are violative of the constitutional mandate of full protection to labor, 34

whether local or overseas, because it deprives overseas Filipino workers,

such as seafarers, an opportunity to become regular employees without valid

and serious reasons. The petitioner maintains that the decision is

discriminatory and violates the constitutional provision on equal protection of

the laws, in addition to being partial to and overly protective of foreign

employers.

The respondents, on the other hand, asseverate that there is no law or

administrative rule or regulation imposing an obligation to rehire a seafarer

upon the completion of his contract. Their refusal to secure the services of

the petitioner after the expiration of his contract can never be tantamount to

a termination. The respondents aver that the petitioner is not entitled to

backwages, not only because it is without factual justification but also

because it is not warranted under the law. Furthermore, the respondents

assert that the rulings in the Coyoca v. NLRC,35 and the latest Millares case

remain good and valid precedents that need to be reaffirmed. The

respondents cited the ruling of the Court in Coyoca case where the Court

ruled that a Filipino seamans contract does not provide for separation or

termination pay because it is governed by the Rules and Regulations

Governing Overseas Employment.

The contention of the respondents is correct.

In a catena of cases, this Court has consistently ruled that seafarers are

contractual, not regular, employees.

In Brent School, Inc. v. Zamora,36 the Court ruled that seamen and overseas

contract workers are not covered by the term "regular employment" as

defined in Article 280 of the Labor Code. The Court said in that case:

The question immediately provoked ... is whether or not a voluntary

agreement on a fixed term or period would be valid where the employee "has

been engaged to perform activities which are usually necessary or desirable

in the usual business or trade of the employer." The definition seems non

sequitur. From the premise that the duties of an employee entail "activities

which are usually necessary or desirable in the usual business or trade of the

employer" the conclusion does not necessarily follow that the employer

and employee should be forbidden to stipulate any period of time for the

performance of those activities. There is nothing essentially contradictory

between a definite period of an employment contract and the nature of the

employees duties set down in that contract as being "usually necessary or

desirable in the usual business or trade of the employer." The concept of the

employees duties as being "usually necessary or desirable in the usual

business or trade of the employer" is not synonymous with or identical to

employment with a fixed term. Logically, the decisive determinant in term

employment should not be the activities that the employee is called upon to

perform, but the day certain agreed upon by the parties for the

commencement and termination of their employment relationship, a day

certain being understood to be "that which must necessarily come, although

it may not be known when." Seasonal employment, and employment for a

particular project are merely instances of employment in which a period,

were not expressly set down, is necessarily implied.37

...

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 9

Some familiar examples may be cited of employment contracts which may

be neither for seasonal work nor for specific projects, but to which a fixed

term is an essential and natural appurtenance: overseas employment

contracts, for one, to which, whatever the nature of the engagement, the

concept of regular employment with all that it implies does not appear ever

to have been applied, Article 280 of the Labor Code notwithstanding; also

appointments to the positions of dean, assistant dean, college secretary,

principal, and other administrative offices in educational institutions, which

are by practice or tradition rotated among the faculty members, and where

fixed terms are a necessity without which no reasonable rotation would be

possible. ... 38

...

Accordingly, and since the entire purpose behind the development of

legislation culminating in the present Article 280 of the Labor Code clearly

appears to have been, as already observed, to prevent circumvention of the

employees right to be secure in his tenure, the clause in said article

indiscriminately and completely ruling out all written or oral agreements

conflicting with the concept of regular employment as defined therein should

be construed to refer to the substantive evil that the Code itself has singled

out: agreements entered into precisely to circumvent security of tenure. It

should have no application to instances where a fixed period of employment

was agreed upon knowingly and voluntarily by the parties, without any force,

duress or improper pressure being brought to bear upon the employee and

absent any other circumstances vitiating his consent, or where it

satisfactorily appears that the employer and employee dealt with each other

on more or less equal terms with no moral dominance whatever being

exercised by the former over the latter. Unless, thus, limited in its purview,

the law would be made to apply to purposes other than those explicitly

stated by its framers; it thus becomes pointless and arbitrary, unjust in its

effects and apt to lead to absurd and unintended consequences.39

The Court made the same ruling in Coyoca v. National Labor Relations

Commission40 and declared that a seafarer, not being a regular employee, is

not entitled to separation or termination pay.

Furthermore, petitioners contract did not provide for separation benefits. In

this connection, it is important to note that neither does the POEA standard

employment contract for Filipino seamen provide for such benefits.

As a Filipino seaman, petitioner is governed by the Rules and Regulations

Governing Overseas Employment and the said Rules do not provide for

separation or termination pay. ...

...

Therefore, although petitioner may not be a regular employee of private

respondent, the latter would still have been liable for payment of the

benefits had the principal failed to pay the same. 41

In the July 29, 2002 Resolution of this Court in Millares v. National Labor

Relations Commission,42 it reiterated its ruling that seafarers are contractual

employees and, as such, are not covered by Article 280 of the Labor Code of

the Philippines:

From the foregoing cases, it is clear that seafarers are considered contractual

employees. They cannot be considered as regular employees under Article

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 10

280 of the Labor Code. Their employment is governed by the contracts they

sign every time they are rehired and their employment is terminated when

the contract expires. Their employment is contractually fixed for a certain

period of time. They fall under the exception of Article 280 whose

employment has been fixed for a specific project or undertaking the

completion or termination of which has been determined at the time of

engagement of the employee or where the work or services to be performed

is seasonal in nature and the employment is for the duration of the season.

We need not depart from the rulings of the Court in the two aforementioned

cases which indeed constitute stare decisis with respect to the employment

status of seafarers.

...

... The Standard Employment Contract governing the Employment of All

Filipino Seamen on Board Ocean-Going Vessels of the POEA, particularly in

Part I, Sec. C, specifically provides that the contract of seamen shall be for a

fixed period. And in no case should the contract of seamen be longer than 12

months. It reads:

Section C. Duration of Contract

The period of employment shall be for a fixed period but in no case to

exceed 12 months and shall be stated in the Crew Contract. Any extension of

the Contract period shall be subject to the mutual consent of the parties.

Petitioners make much of the fact that they have been continually re-hired or

their contracts renewed before the contracts expired (which has admittedly

been going on for twenty [20] years). By such circumstance they claim to

have acquired regular status with all the rights and benefits appurtenant to

it. Such contention is untenable. Undeniably, this circumstance of continuous

re-hiring was dictated by practical considerations that experienced crew

members are more preferred. Petitioners were only given priority or

preference because of their experience and qualifications but this does not

detract the fact that herein petitioners are contractual employees. They can

not be considered regular employees. We quote with favor the explanation of

the NLRC in this wise:

xxx The reference to "permanent" and "probationary" masters and

employees in these papers is a misnomer and does not alter the fact that the

contracts for enlistment between complainants-appellants and respondentappellee Esso International were for a definite periods of time, ranging from

8 to 12 months. Although the use of the terms "permanent" and

"probationary" is unfortunate, what is really meant is "eligible for-re-hire."

This is the only logical conclusion possible because the parties cannot and

should not violate POEAs requirement that a contract of enlistment shall be

for a limited period only; not exceeding twelve (12) months.

From all the foregoing, we hereby state that petitioners are not considered

regular or permanent employees under Article 280 of the Labor Code.

Petitioners employment have automatically ceased upon the expiration of

their contracts of enlistment (COE). Since there was no dismissal to speak of,

it follows that petitioners are not entitled to reinstatement or payment of

separation pay or backwages, as provided by law. 43

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 11

The Court ruled that the employment of seafarers for a fixed period is not

discriminatory against seafarers and in favor of foreign employers. As

explained by this Court in its July 29, 2002 Resolution in Millares:

Moreover, it is an accepted maritime industry practice that employment of

seafarers are for a fixed period only. Constrained by the nature of their

employment which is quite peculiar and unique in itself, it is for the mutual

interest of both the seafarer and the employer why the employment status

must be contractual only or for a certain period of time. Seafarers spend

most of their time at sea and understandably, they can not stay for a long

and an indefinite period of time at sea. Limited access to shore society

during the employment will have an adverse impact on the seafarer. The

national, cultural and lingual diversity among the crew during the COE is a

reality that necessitates the limitation of its period.44

In Pentagon International Shipping, Inc. v. William B. Adelantar,45 the Court

cited its rulings in Millares and Coyoca and reiterated that a seafarer is not a

regular employee entitled to backwages and separation pay:

Therefore, Adelantar, a seafarer, is not a regular employee as defined in

Article 280 of the Labor Code. Hence, he is not entitled to full backwages and

separation pay in lieu of reinstatement as provided in Article 279 of the

Labor Code. As we held in Millares, Adelantar is a contractual employee

whose rights and obligations are governed primarily by [the] Rules and

Regulations of the POEA and, more importantly, by R.A. 8042, or the Migrant

Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act of 1995.

The latest ruling of the Court in Marcial Gu-Miro v. Rolando C. Adorable and

Bergesen D.Y. Manila46 reaffirmed yet again its rulings that a seafarer is

employed only on a contractual basis:

Clearly, petitioner cannot be considered as a regular employee

notwithstanding that the work he performs is necessary and desirable in the

business of respondent company. As expounded in the above-mentioned

Millares Resolution, an exception is made in the situation of seafarers. The

exigencies of their work necessitates that they be employed on a contractual

basis.

Thus, even with the continued re-hiring by respondent company of petitioner

to serve as Radio Officer onboard Bergesens different vessels, this should be

interpreted not as a basis for regularization but rather a series of contract

renewals sanctioned under the doctrine set down by the second Millares

case. If at all, petitioner was preferred because of practical considerations

namely, his experience and qualifications. However, this does not alter the

status of his employment from being contractual.

The petitioner failed to convince the Court why it should restate its decision

in Millares and reverse its July 29, 2002 Resolution in the same case.

IN LIGHT OF ALL THE FOREGOING, the petition is hereby DENIED. The

assailed Decision dated August 28, 2002 of the Court of Appeals is hereby

AFFIRMED. No pronouncement as to costs.

SO ORDERED.

2. Sunace vs NLRC

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 12

SUNACE INTERNATIONAL

MANAGEMENT SERVICES, INC.

Petitioner,

- versus

NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION, Second Division; HON.

ERNESTO S. DINOPOL, in his capacity as Labor Arbiter, NLRC; NCR,

Arbitration Branch, Quezon City and DIVINA A. MONTEHERMOZO,

Respondents.

DECISION

CARPIO MORALES, J.:

Petitioner, Sunace International Management Services (Sunace), a

corporation duly organized and existing under the laws of the Philippines,

deployed to Taiwan Divina A. Montehermozo (Divina) as a domestic helper

under a 12-month contract effective February 1, 1997.[1] The deployment

was with the assistance of a Taiwanese broker, Edmund Wang, President of

Jet Crown International Co., Ltd.

After her 12-month contract expired on February 1, 1998, Divina

continued working for her Taiwanese employer, Hang Rui Xiong, for two more

years, after which she returned to the Philippines on February 4, 2000.

Shortly after her return or on February 14, 2000, Divina filed a

complaint[2] before the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) against

Sunace, one Adelaide Perez, the Taiwanese broker, and the employer-foreign

principal alleging that she was jailed for three months and that she was

underpaid.

The following day or on February 15, 2000, Labor Arbitration Associate

Regina T. Gavin issued Summons[3] to the Manager of Sunace, furnishing it

with a copy of Divinas complaint and directing it to appear for mandatory

conference on February 28, 2000.

The scheduled mandatory conference was reset. It appears to have

been concluded, however.

On April 6, 2000, Divina filed her Position Paper[4] claiming that under

her original one-year contract and the 2-year extended contract which was

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 13

with the knowledge and consent of Sunace, the following amounts

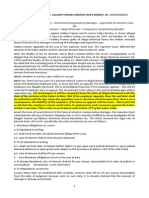

representing income tax and savings were deducted:

Year

Deduction for

Income Tax

Deduction

Savings

1997

NT10,450.00

NT23,100.00

1998

NT9,500.00

NT36,000.00

1999

NT13,300.00

NT36,000.00;[5]

for

and while the amounts deducted in 1997 were refunded to her, those

deducted in 1998 and 1999 were not. On even date, Sunace, by its

Proprietor/General Manager Maria Luisa Olarte, filed its Verified Answer and

Position Paper,[6] claiming as follows, quoted verbatim:

COMPLAINANT IS NOT ENTITLED

FOR THE REFUND OF HER 24 MONTHS

SAVINGS

3. Complainant could not anymore claim nor entitled for the refund of

her 24 months savings as she already took back her saving

already last year and the employer did not deduct any money

from her salary, in accordance with a Fascimile Message from

the respondent SUNACEs employer, Jet Crown International Co.

Ltd., a xerographic copy of which is herewith attached as ANNEX

2 hereof;

COMPLAINANT IS NOT ENTITLED

TO REFUND OF HER 14 MONTHS TAX

AND PAYMENT OF ATTORNEYS FEES

4. There is no basis for the grant of tax refund to the complainant as

the she finished her one year contract and hence, was not

illegally dismissed by her employer. She could only lay claim

over the tax refund or much more be awarded of damages such

as attorneys fees as said reliefs are available only when the

dismissal of a migrant worker is without just valid or lawful cause

as defined by law or contract.

The rationales behind the award of tax refund and payment of

attorneys fees is not to enrich the complainant but to

compensate him for actual injury suffered. Complainant did not

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 14

suffer injury, hence, does not deserve to be compensated for

whatever kind of damages.

Hence, the complainant has NO cause of action against respondent

SUNACE for monetary claims, considering that she has been

totally paid of all the monetary benefits due her under her

Employment Contract to her full satisfaction.

6.

Furthermore, the tax deducted from her salary is in

compliance with the Taiwanese law, which respondent SUNACE

has no control and complainant has to obey and this Honorable

Office has no authority/jurisdiction to intervene because the

power to tax is a sovereign power which the Taiwanese

Government is supreme in its own territory. The sovereign power

of taxation of a state is recognized under international law and

among sovereign states.

7. That respondent SUNACE respectfully reserves the right to file

supplemental Verified Answer and/or Position Paper to

substantiate its prayer for the dismissal of the above case

against the herein respondent. AND BY WAY OF x x x x (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

Reacting to Divinas Position Paper, Sunace filed on April 25, 2000 an . . .

ANSWER TO COMPLAINANTS POSITION PAPER [7]

alleging that Divinas 2-year extension of

her contract was without its knowledge and consent, hence, it had no liability

attaching to any claim arising therefrom, and Divina in fact executed a

Waiver/Quitclaim

and

Release

of

Responsibility

and

an

Affidavit

Desistance, copy of each document was annexed to said . . .

of

ANSWER TO

COMPLAINANTS POSITION PAPER.

To Sunaces . . .

ANSWER TO COMPLAINANTS POSITION PAPER,

Divina filed a 2-page reply,[8]

without, however, refuting Sunaces disclaimer of knowledge of the extension

of her contract and without saying anything about the Release, Waiver and

Quitclaim and Affidavit of Desistance.

The Labor Arbiter, rejected Sunaces claim that the extension of Divinas

contract for two more years was without its knowledge and consent in this

wise:

We reject Sunaces submission that it should not be

held responsible for the amount withheld because her

contract was extended for 2 more years without its

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 15

knowledge and consent because as Annex B[9] shows,

Sunace

and

Edmund

Wang

have

not

stopped

communicating with each other and yet the matter of the

contracts extension and Sunaces alleged non-consent

thereto has not been categorically established.

What Sunace should have done was to write to POEA

about the extension and its objection thereto, copy

furnished the complainant herself, her foreign employer,

Hang Rui Xiong and the Taiwanese broker, Edmund Wang.

And because it did not, it is presumed to have

consented to the extension and should be liable for

anything that resulted thereform (sic).[10] (Underscoring

supplied)

The Labor Arbiter rejected too Sunaces argument that it is not liable on

account of Divinas execution of a Waiver and Quitclaim and an Affidavit of

Desistance. Observed the Labor Arbiter:

Should the parties arrive at any agreement as to the whole

or any part of the dispute, the same shall be reduced to writing

and signed by the parties and their respective counsel (sic), if

any, before the Labor Arbiter.

The settlement shall be approved by the Labor Arbiter after

being satisfied that it was voluntarily entered into by the parties

and after having explained to them the terms and consequences

thereof.

A compromise agreement entered into by the parties not in

the presence of the Labor Arbiter before whom the case is

pending shall be approved by him, if after confronting the

parties, particularly the complainants, he is satisfied that they

understand the terms and conditions of the settlement and that

it was entered into freely voluntarily (sic) by them and the

agreement is not contrary to law, morals, and public policy.

And because no consideration is indicated in the

documents, we strike them down as contrary to law, morals, and

public policy.[11]

He accordingly decided in favor of Divina, by decision of October 9, 2000,[12]

the dispositive portion of which reads:

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 16

Wherefore, judgment is hereby rendered ordering

respondents SUNACE INTERNATIONAL SERVICES and its owner

ADELAIDA PERGE, both in their personal capacities and as agent

of Hang Rui Xiong/Edmund Wang to jointly and severally pay

complainant DIVINA A. MONTEHERMOZO the sum of NT91,950.00

in its peso equivalent at the date of payment, as refund for the

amounts which she is hereby adjudged entitled to as earlier

discussed plus 10% thereof as attorneys fees since compelled to

litigate, complainant had to engage the services of counsel.

SO ORDERED.[13] (Underescoring supplied)

On appeal of Sunace, the NLRC, by Resolution of April 30, 2002,[14]

affirmed the Labor Arbiters decision.

Via petition for certiorari,[15] Sunace elevated the case to the Court of

Appeals which dismissed it outright by Resolution of November 12, 2002,[16]

the full text of which reads:

The petition for certiorari faces outright dismissal.

The petition failed to allege facts constitutive of grave

abuse of discretion on the part of the public respondent

amounting to lack of jurisdiction when the NLRC affirmed the

Labor Arbiters finding that petitioner Sunace International

Management Services impliedly consented to the extension of

the contract of private respondent Divina A. Montehermozo. It is

undisputed that petitioner was continually communicating with

private respondents foreign employer (sic). As agent of the

foreign principal, petitioner cannot profess ignorance of such

extension as obviously, the act of the principal extending

complainant (sic) employment contract necessarily bound

it. Grave abuse of discretion is not present in the case at bar.

ACCORDINGLY, the petition is hereby DENIED DUE

COURSE and DISMISSED.[17]

SO ORDERED.

(Emphasis on words in capital letters in the original;

emphasis on words in small letters and underscoring supplied)

Its Motion for Reconsideration having been denied by the appellate court by

Resolution of January 14, 2004,[18] Sunace filed the present petition for

review on certiorari.

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 17

The Court of Appeals affirmed the Labor Arbiter and NLRCs finding that

Sunace knew of and impliedly consented to the extension of Divinas 2-year

contract. It went on to state that It is undisputed that [Sunace] was

continually communicating with [Divinas] foreign employer. It thus concluded

that [a]s agent of the foreign principal, petitioner cannot profess ignorance of

such extension as obviously, the act of the principal extending complainant

(sic) employment contract necessarily bound it.

Contrary to the Court of Appeals finding, the alleged continuous

communication was with the Taiwanese broker Wang, not with the foreign

employer Xiong.

The February 21, 2000 telefax message from the Taiwanese broker to

Sunace, the only basis of a finding of continuous communication, reads

verbatim:

xxxx

Regarding to Divina, she did not say anything

about her saving in police station. As we contact with

her employer, she took back her saving already last

years. And they did not deduct any money from her

salary. Or she will call back her employer to check it

again. If her employer said yes! we will get it back for

her.

Thank you and best regards.

(sgd.)

Edmund Wang

President[19]

The finding of the Court of Appeals solely on the basis of the abovequoted telefax message, that Sunace continually communicated with the

foreign principal (sic) and therefore was aware of and had consented to the

execution of the extension of the contract is misplaced. The message does

not provide evidence that Sunace was privy to the new contract executed

after the expiration on February 1, 1998 of the original contract. That Sunace

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 18

and the Taiwanese broker communicated regarding Divinas allegedly

withheld savings does not necessarily mean that Sunace ratified the

extension of the contract. As Sunace points out in its Reply[20] filed before

the Court of Appeals,

As can be seen from that letter communication, it

was just an information given to the petitioner that the

private respondent had t[aken] already her savings from

her foreign employer and that no deduction was made on

her salary. It contains nothing about the extension or the

petitioners consent thereto.[21]

Parenthetically, since the telefax message is dated February 21, 2000,

it is safe to assume that it was sent to enlighten Sunace who had been

directed, by Summons issued on February 15, 2000, to appear on February

28, 2000 for a mandatory conference following Divinas filing of the complaint

on February 14, 2000.

Respecting the Court of Appeals following dictum:

As agent of its foreign principal, [Sunace] cannot profess

ignorance of such an extension as obviously, the act of its

principal extending [Divinas] employment contract necessarily

bound it,[22]

it too is a misapplication, a misapplication of the theory of imputed

knowledge.

The theory of imputed knowledge ascribes the knowledge of the agent,

Sunace, to the principal, employer Xiong, not the other way around.[23]

The knowledge of the principal-foreign employer cannot, therefore, be

imputed to its agent Sunace.

There being no substantial proof that Sunace knew of and consented to

be bound under the 2-year employment contract extension, it cannot be said

to be privy thereto. As such, it and its owner cannot be held solidarily liable

for any of Divinas claims arising from the 2-year employment extension. As

the New Civil Code provides,

Contracts take effect only between the parties, their

assigns, and heirs, except in case where the rights and

obligations arising from the contract are not transmissible

by their nature, or by stipulation or by provision of law.[24]

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 19

Furthermore, as Sunace correctly points out, there was an implied

revocation of its agency relationship with its foreign principal when, after the

termination of the original employment contract, the foreign principal

directly negotiated with Divina and entered into a new and separate

employment contract in Taiwan. Article 1924 of the New Civil Code reading

The agency is revoked if the principal directly manages the

business entrusted to the agent, dealing directly with third

persons.

thus applies.

In light of the foregoing discussions, consideration of the validity of the

Waiver and Affidavit of Desistance which Divina executed in favor of Sunace

is rendered unnecessary.

WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED. The challenged resolutions of

the Court of Appeals are hereby REVERSED and SET ASIDE. The complaint

of respondent Divina A. Montehermozo against petitioner is DISMISSED.

SO ORDERED.

3. Southeastern Shipping vs Navarro

SOUTHEASTERN SHIPPING, SOUTHEASTERN SHIPPING GROUP, LTD.,

Petitioners,

- versus

FEDERICO U. NAVARRA, JR., Respondent.

DECISION

DEL CASTILLO, J.

Money claims arising from employer-employee relations, including those specified

in the Standard Employment Contract for Seafarers, prescribe within three years

from the time the cause of action accrues.[1] However, for death benefit claims to

prosper, the seafarers death must have occurred during the effectivity of said

contract.

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 20

This Petition for Review assails the January 31, 2005 Decision[2] and the

April 4, 2005 Resolution [3] of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. SP. No. 85584.

The CA dismissed the petition for certiorari filed before it assailing the May 7, 2003

Decision[4] of the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) ordering

petitioners to pay to Evelyn J. Navarra (Evelyn), the surviving spouse of deceased

Federico U. Navarra, Jr. (Federico), death compensation, allowances of the three

minor children, burial expenses plus 10% of the total monetary awards as and for

attorney's fees.

Factual Antecedents

Petitioner Southeastern Shipping, on behalf of its foreign principal, petitioner

Southeastern Shipping Group, Ltd., hired Federico to work on board the vessel

"George McLeod." Federico signed 10 successive separate employment contracts

of varying durations covering the period from October 5, 1995 to March 30, 1998.

His latest contract was approved by the Philippine Overseas Employment

Administration (POEA) on January 21, 1998 for 56 days extendible for another 56

days. He worked as roustabout during the first contract and as a motorman during

the succeeding contracts.

On March 6, 1998, Federico, while on board the vessel, complained of

having a sore throat and on and off fever with chills. He also developed a soft

mass on the left side of his neck. He was given medication.

On March 30, 1998, Federico arrived back in the Philippines. On April 21,

1998 the specimen excised from his neck lymph node was found negative for

malignancy.[5] On June 4, 1998, he was diagnosed at the Philippine General

Hospital to be suffering from a form of cancer called Hodgkin's Lymphoma,

Nodular Sclerosing Type (also known as Hodgkin's Disease). This diagnosis was

confirmed in another test conducted at the Medical Center Manila on June 8, 1998.

On September 6, 1999, Federico filed a complaint against petitioners with

the arbitration branch of the NLRC claiming entitlement to disability benefits, loss

of earning capacity, moral and exemplary damages, and attorney's fees.

During the pendency of the case, on April 29, 2000, Federico died. His

widow, Evelyn, substituted him as party complainant on her own behalf and in

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 21

behalf of their three children. The claim for disability benefits was then converted

into a claim for death benefits.

Ruling of the Labor Arbiter

On May 10, 2000, Labor Arbiter Ermita T. Abrasaldo-Cuyuca rendered a Decision

dismissing the complaint on the ground that "Hodgkin's Lymphoma is not one of

the occupational or compensable diseases or the exact cause is not known," the

dispositive portion of which states:

WHEREFORE, premises considered judgment

rendered dismissing the complaint for lack of merit.

is

hereby

SO ORDERED.[6]

Evelyn appealed the Decision to the NLRC.

Ruling of the NLRC

On May 7, 2003, the NLRC rendered a Decision reversing that of the Labor

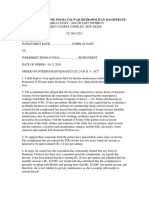

Arbiter, the dispositive portion of which provides:

WHEREFORE, the appealed decision is REVERSED and SET

ASIDE. Judgment is hereby rendered ordering the respondents

Southeastern Shipping/Southeastern Shipping Group Ltd. jointly and

severally, to pay complainant Evelyn J. Navarra the following:

Death compensation

Minor child allowance

(3 x US$ 7,000)

Burial expense

Total

US$ 50,000.00

21,000.00

1,000.00

US$ 72,000.00

Plus 10% of the total monetary awards as and for attorney's

fees.

SO ORDERED.[7]

Petitioners filed a Motion for Reconsideration which was denied by the

NLRC. They, thus, filed a petition for certiorari with the CA.

Ruling of the Court of Appeals

The CA found that the claim for benefits had not yet prescribed despite the

complaint being filed more than one year after Federico's return to the Philippines.

It also found that although Federico died 17 months after his contract had expired,

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 22

his heirs could still claim death benefits because the cause of his death was the

same illness for which he was repatriated. The dispositive portion of the CA

Decision states:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, petition is hereby

DISMISSED for lack of merit and the May 7, 2003 Decision of the

National Labor Relations Commission is hereby AFFIRMED en toto.

SO ORDERED.[8]

After the denial by the CA of their motion for reconsideration, petitioners

filed the present petition for review.

Issues

Petitioners raise the following issues:

I

THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN RULING THAT PRESCRIPTION

DOES NOT APPLY DESPITE THE LATE FILING OF THE COMPLAINT OF

THE RESPONDENT FEDERICO U. NAVARRA, JR.

II

THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN RULING THAT

HODGKIN'S DISEASE IS A COMPENSABLE ILLNESS.

III

THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN ITS CONCLUSION THAT

PETITIONERS ARE LIABLE FOR THE DEATH OF THE RESPONDENT AS

SUCH DEATH WAS DURING THE TERM OF HIS EMPLOYMENT

CONTRACT.[9]

Petitioners' Arguments

Petitioners contend that the factual findings of the CA were not supported

by sufficient evidence. They argue that as can be seen from the medical report of

Dr. Salim Marangat Paul, Federico suffered from and was treated for Acute

Respiratory Tract Infection, not Hodgkin's Disease, during his employment in

March 1998. They further contend that Federico returned to the Philippines on

March 30, 1998 because he had already finished his contract, not because he had

to undergo further medical treatment.

They also insist that the complaint has already prescribed. Despite having

been diagnosed on June 4, 1998 of Hodgkin's Disease, the complaint was filed

only on September 6, 1999, one year and five months after Federico arrived in

Manila from Qatar.

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 23

They also posit that respondents are not entitled to the benefits claimed

because Federico did not die during the term of his contract and the cause of his

death was not contracted by him during the term of his contract.

Respondents' Arguments

Respondents on the other hand contend that the complaint has not

prescribed and that the prescriptive period for filing seafarer claims is three years

from the time the cause of action accrued. They claim that in case of conflict

between the law and the POEA Contract, it is the law that prevails.

Respondents also submit that Federico contracted on board the vessel the

illness which later caused his death, hence it is compensable.

Our Ruling

The petition is partly meritorious.

Prescription

The employment contract signed by Federico stated that "the same shall be

deemed an integral part of the Standard Employment Contract for Seafarers,"

Section 28 of which states:

SECTION 28. JURISDICTION

The Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) or

the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) shall have original

and exclusive jurisdiction over any and all disputes or controversies

arising out of or by virtue of this Contract.

Recognizing the peculiar nature of overseas shipboard

employment, the employer and the seafarer agree that all claims

arising from this contract shall be made within one (1) year from the

date of the seafarer's return to the point of hire.

On the other hand, the Labor Code states:

Art. 291. Money claims.-All money claims arising from

employer-employee relations during the effectivity of this Code shall

be filed within three (3) years from the time the cause of action

accrued; otherwise they shall forever be barred.

The Constitution affirms labor as a primary social economic force.[10] Along

this vein, the State vowed to afford full protection to labor, local and overseas,

organized and unorganized, and promote full employment and equality of

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 24

employment opportunities for all.[11]

"The employment of seafarers, including claims for death benefits, is

governed by the contracts they sign every time they are hired or rehired; and as

long as the stipulations therein are not contrary to law, morals, public order or

public policy, they have the force of law between the parties."[12]

In Cadalin v. POEA's Administrator,[13] we held that Article 291 of the Labor

Code covers all money claims from employer-employee relationship. It is not

limited to money claims recoverable under the Labor Code, but applies

also to claims of overseas contract workers.[14]

Based on the foregoing, it is therefore clear that Article 291 is the law

governing the prescription of money claims of seafarers, a class of overseas

contract workers. This law prevails over Section 28 of the Standard Employment

Contract for Seafarers which provides for claims to be brought only within one

year from the date of the seafarers return to the point of hire. Thus, for the

guidance of all, Section 28 of the Standard Employment Contract for Seafarers,

insofar as it limits the prescriptive period within which the seafarers may file their

money claims, is hereby declared null and void. The applicable provision is Article

291 of the Labor Code, it being more favorable to the seafarers and more in

accord with the States declared policy to afford full protection to labor. The

prescriptive period in the present case is thus three years from the time the cause

of action accrues.

In the present case, there is no exact showing of when the cause of action

accrued. Nevertheless, it could not have accrued earlier than January 21, 1998

which is the date of his last contract. Hence, the claim has not yet prescribed,

since the complaint was filed with the arbitration branch of the NLRC on

September 6, 1999.

Compensability and Liability

In petitions for review on certiorari, only questions of law may be raised, the

only exceptions being when the factual findings of the appellate court are

erroneous, absurd, speculative, conjectural, conflicting, or contrary to the findings

culled by the court of origin. Considering the conflicting findings of the NLRC, the

CA and the Labor Arbiter, we are impelled to resolve the factual issues in this case

along with the legal ones.[15]

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 25

Section 20 of the Standard Terms and Conditions Governing the

Employment of Filipino Seafarers On-Board Ocean-Going Vessels states:

A.

COMPENSATION AND BENEFITS FOR DEATH

1.

In case of death of the seafarer during the term of his

contact, the employer shall pay his beneficiaries the

Philippine currency equivalent to the amount of Fifty

Thousand US Dollars (US$50,000) and an additional

amount of Seven Thousand US Dollars (US$7,000) to

each child under the age of twenty-one (21) but not

exceeding four children, at the exchange rate prevailing

during the time of payment. (Emphasis supplied)

Thus, as we declared in Gau Sheng Phils., Inc. v. Joaquin, Hermogenes v.

Oseo Shipping Services, Inc., Prudential Shipping and Management Corporation v.

Sta. Rita, Klaveness Maritime Agency, Inc. v. Beneficiaries of Allas, in order to avail

of death benefits, the death of the employee should occur during the effectivity of

the employment contract.[16] For emphasis, we reiterate that the death of a

seaman during the term of employment makes the employer liable to his heirs for

death compensation benefits, but if the seaman dies after the termination of his

contract of employment, his beneficiaries are not entitled to the death benefits.

[17] Federico did not die while he was under the employ of petitioners. His

contract of employment ceased when he arrived in the Philippines on March 30,

1998, whereas he died on April 29, 2000. Thus, his beneficiaries are not entitled to

the death benefits under the Standard Employment Contract for Seafarers.

Moreover, there is no showing that the cancer was brought about by

Federico's stint on board petitioners' vessel. The records show that he got sick a

month after he boarded M/V George Mcleod. He was then brought to a doctor who

diagnosed him to have acute respiratory tract infection. It was only on June 6,

1998, more than two months after his contract with petitioners had expired, that

he was diagnosed to have Hodgkin's Disease. There is no proof and we are not

convinced that his exposure to the motor fumes of the vessel, as alleged by

Federico, caused or aggravated his Hodgkin's Disease.

While the Court adheres to the principle of liberality in favor of the seafarer

in construing the Standard Employment Contract, we cannot allow claims for

compensation based on surmises. When the evidence presented negates

compensability, we have no choice but to deny the claim, lest we cause injustice

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 26

to the employer.

The law in protecting the rights of the employees, authorizes neither

oppression nor self-destruction of the employer there may be cases where the

circumstances warrant favoring labor over the interests of management but never

should the scale be so tilted as to result in an injustice to the employer.[18]

WHEREFORE, the petition is PARTLY GRANTED. The January 31, 2005

Decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 85584 holding that the claim for

death benefits has not yet prescribed is AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION that

petitioners are not liable to pay to respondents death compensation benefits for

lack of showing that Federicos disease was brought about by his stint on board

petitioners vessels and also considering that his death occurred after the

effectivity of his contract.

SO ORDERED.

4. Catan vs NLRC

MANUELA S. CATAN/M.S. CATAN PLACEMENT AGENCY, petitioners,

vs.

THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION, PHILIPPINE

OVERSEAS EMPLOYMENT ADMINISTRATION and FRANCISCO D.

REYES, respondents.

Demetria Reyes, Merris & Associates for petitioners.

The Solicitor General for public respondents.

Bayani G. Diwa for private respondent.

CORTES, J.:

Petitioner, in this special civil action for certiorari, alleges grave abuse of

discretion on the part of the National Labor Relations Commission in an effort

to nullify the latters resolution and thus free petitioner from liability for the

disability suffered by a Filipino worker it recruited to work in Saudi Arabia.

This Court, however, is not persuaded that such an abuse of discretion was

committed. This petition must fail.

The facts of the case are quite simple.

Petitioner, a duly licensed recruitment agency, as agent of Ali and Fahd

Shabokshi Group, a Saudi Arabian firm, recruited private respondent to work

in Saudi Arabia as a steelman.

The term of the contract was for one year, from May 15,1981 to May 14,

1982. However, the contract provided for its automatic renewal:

FIFTH: The validity of this Contract is for ONE YEAR commencing

from the date the SECOND PARTY assumes hill port. This Contract

is renewable automatically if neither of the PARTIES notifies the

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 27

other PARTY of his wishes to terminate the Contract by at least

ONE MONTH prior to the expiration of the contractual period.

[Petition, pp. 6-7; Rollo, pp. 7-8].

The contract was automatically renewed when private respondent was not

repatriated by his Saudi employer but instead was assigned to work as a

crusher plant operator. On March 30, 1983, while he was working as a

crusher plant operator, private respondent's right ankle was crushed under

the machine he was operating.

On May 15, 1983, after the expiration of the renewed term, private

respondent returned to the Philippines. His ankle was operated on at the Sta.

Mesa Heights Medical Center for which he incurred expenses.

On September 9, 1983, he returned to Saudi Arabia to resume his work. On

May 15,1984, he was repatriated.

Upon his return, he had his ankle treated for which he incurred further

expenses.

On the basis of the provision in the employment contract that the employer

shall compensate the employee if he is injured or permanently disabled in

the course of employment, private respondent filed a claim, docketed as

POEA Case No. 84-09847, against petitioner with respondent Philippine

Overseas Employment Administration. On April 10, 1986, the POEA rendered

judgment in favor of private respondent, the dispositive portion of which

reads:

WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered in favor of the

complainant and against the respondent, ordering the latter to

pay to the complainant:

1. SEVEN THOUSAND NINE HUNDRED EIGHTY-FIVE PESOS and

60/100 (P7,985.60), Philippine currency, representing disability

benefits;

2. TWENTY-FIVE THOUSAND NINETY-SIX Philippine pesos and

20/100 (29,096.20) representing reimbursement for medical

expenses;

3. Ten percent (10%) of the abovementioned amounts as and for

attorney's fees. [NLRC Resolution, p. 1; Rollo, p. 16].

On appeal, respondent NLRC affirmed the decision of the POEA in a

resolution dated December 12, 1986.

Not satisfied with the resolution of the POEA, petitioner instituted the instant

special civil action for certiorari, alleging grave abuse of discretion on the

part of the NLRC.

1. Petitioner claims that the NLRC gravely abused its discretion when it ruled

that petitioner was liable to private respondent for disability benefits since at

the time he was injured his original employment contract, which petitioner

facilitated, had already expired. Further, petitioner disclaims liability on the

ground that its agency agreement with the Saudi principal had already

expired when the injury was sustained.

There is no merit in petitioner's contention.

Private respondents contract of employment can not be said to have expired

on May 14, 1982 as it was automatically renewed since no notice of its

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 28

termination was given by either or both of the parties at least a month

before its expiration, as so provided in the contract itself. Therefore, private

respondent's injury was sustained during the lifetime of the contract.

A private employment agency may be sued jointly and solidarily with its

foreign principal for violations of the recruitment agreement and the

contracts of employment:

Sec. 10. Requirement before recruitment. Before recruiting any

worker, the private employment agency shall submit to the

Bureau the following documents:

(a) A formal appointment or agency contract executed by a

foreign-based employer in favor of the license holder to recruit

and hire personnel for the former ...

xxx xxx xxx

2. Power of the agency to sue and be sued jointly and

solidarily with the principal or foreign-based

employer for any of the violations of the recruitment

agreement and the contracts of employment.

[Section 10(a) (2) Rule V, Book I, Rules to Implement

the Labor Code].

Thus, in the recent case of Ambraque International Placement & Services v.

NLRC [G.R. No. 77970, January 28,1988], the Court ruled that a recruitment

agency was solidarily liable for the unpaid salaries of a worker it recruited for

employment in Saudi Arabia.

Even if indeed petitioner and the Saudi principal had already severed their

agency agreement at the time private respondent was injured, petitioner

may still be sued for a violation of the employment contract because no

notice of the agency agreement's termination was given to the private

respondent:

Art 1921. If the agency has been entrusted for the purpose of

contra with specified persons, its revocation shall not prejudice

the latter if they were not given notice thereof. [Civil Code].

In this connection the NLRC elaborated:

Suffice it to state that albeit local respondent M. S. Catan Agency

was at the time of complainant's accident resulting in his

permanent partial disability was (sic) no longer the accredited

agent of its foreign principal, foreign respondent herein, yet its

responsibility over the proper implementation of complainant's

employment/service contract and the welfare of complainant

himself in the foreign job site, still existed, the contract of

employment in question not having expired yet. This must be so,

because the obligations covenanted in the recruitment

agreement entered into by and between the local agent and its

foreign principal are not coterminus with the term of such

agreement so that if either or both of the parties decide to end

the agreement, the responsibilities of such parties towards the

contracted employees under the agreement do not at all end,

but the same extends up to and until the expiration of the

employment contracts of the employees recruited and employed

pursuant to the said recruitment agreement. Otherwise, this will

ELS: Labor Law1

Full Cases (Ravago to Panis)

Twenty19 29

render nugatory the very purpose for which the law governing

the employment of workers for foreign jobs abroad was enacted.

[NLRC Resolution, p. 4; Rollo, p. 18]. (Emphasis supplied).

2. Petitioner contends that even if it is liable for disability benefits, the NLRC

gravely abused its discretion when it affirmed the award of medical expenses

when the said expenses were the consequence of private respondent's

negligence in returning to work in Saudi Arabia when he knew that he was

not yet medically fit to do so.

Again, there is no merit in this contention.

No evidence was introduced to prove that private respondent was not

medically fit to work when he returned to Saudi Arabia. Exhibit "B", a

certificate issued by Dr. Shafquat Niazi, the camp doctor, on November 1,

1983, merely stated that private respondent was "unable to walk properly,

moreover he is still complaining [of] pain during walking and different lower

limbs movement" [Annex "B", Reply; Rollo, p. 51]. Nowhere does it say that

he was not medically fit to work.

Further, since petitioner even assisted private respondent in returning to

work in Saudi Arabia by purchasing his ticket for him [Exhibit "E"; Annex "A",

Reply to Respondents' Comments], it is as if petitioner had certified his

fitness to work. Thus, the NLRC found:

Furthermore, it has remained unrefuted by respondent that

complainant's subsequent departure or return to Saudi Arabia on

September 9, 1983 was with the full knowledge, consent and

assistance of the former. As shown in Exhibit "E" of the record, it

was respondent who facilitated the travel papers of complainant.

[NLRC Resolution, p. 5; Rollo, p. 19].

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, the petition is DISMISSED for lack of

merit, with costs against petitioner.

SO ORDERED.

5. Hornales vs NLRC

MARIO HORNALES, petitioner,

vs.

THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS COMMISSION, JOSE CAYANAN AND

JEAC INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT CONTRACTOR SERVICES,

respondents.

SANDOVAL-GUTIERREZ, J.:

It is sad enough that poverty has impelled many of our countrymen to seek