Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Kenis 085

Hochgeladen von

Chris Buck0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

18 Ansichten6 SeitenN.H. Supreme Court judicial opinion, 2005

Originaltitel

kenis085

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenN.H. Supreme Court judicial opinion, 2005

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

18 Ansichten6 SeitenKenis 085

Hochgeladen von

Chris BuckN.H. Supreme Court judicial opinion, 2005

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 6

Kenis085

NOTICE: This opinion is subject to motions for rehearing under

Rule 22 as well as formal revision before publication in the New

Hampshire Reports. Readers are requested to notify the Reporter,

Supreme Court of New Hampshire, One Noble Drive, Concord, New

Hampshire 03301, of any editorial errors in order that

corrections may be made before the opinion goes to press. Errors

may be reported by E-mail at the following address:

reporter@courts.state.nh.us. Opinions are available on the

Internet by 9:00 a.m. on the morning of their release. The direct

address of the court's home page is:

http://www.courts.state.nh.us/supreme.

THE SUPREME COURT OF NEW HAMPSHIRE

___________________________

Coos

No. 2004-815

TERRY W. KENISON AND DIANA L. KENISON, CO-ADMINSTRATORS OF THE

ESTATE OF BRODY J. KENISON

v.

ANDRE DUBOIS & a.

Argued: April 20, 2005

Opinion Issued: July 18, 2005

McDowell & Osburn, P.A., of Manchester (Joseph F. McDowell,

III and Mark D. Morrissette on the brief, and Mr. Morrissette

orally), for the plaintiffs.

Devine, Millimet & Branch, Professional Association, of

Manchester (Robert C. Dewhirst and Donald L. Smith on the brief,

and Mr. Smith orally), for the defendants.

DALIANIS, J. The plaintiffs, Terry W. Kenison and Diana L.

Kenison, co-administrators of the Estate of Brody J. Kenison,

appeal a ruling of the Superior Court (Vaughan, J.) granting

summary judgment to the defendants, Andre Dubois and the Waumbek

Methna Snowmobile Club (Waumbek). On appeal, the plaintiffs

argue that the trial court erred in ruling that the defendants

are immune from liability under RSA 508:14, I (1997), RSA 212:34,

I (2000) (amended 2003) and RSA 215-A:34, II (2000). We reverse

and remand.

The record reflects the following facts. On the morning of

February 26, 2001, the decedent, Brody Kenison, was riding his

snowmobile on the "Corridor 5" snowmobile trail in Jefferson,

when he collided with a snow-trail grooming machine (snow

groomer) owned by Waumbek and operated by Dubois, resulting in

his death. "Corridor 5" is a recreational trail open year-

round to the public for multiple uses, including use by

snowmobiles. It runs from Portland, Maine, through New Hampshire,

to Montreal, Quebec, and is owned by Portland Pipeline. Waumbek

is a nonprofit snowmobile club that, for over twenty years, has

voluntarily maintained, groomed and developed the portion of the

"Corridor 5" trail where the collision took place. Waumbek

receives compensation to recover its trail-grooming expenses

through a grant-in-aid program sponsored by the State of New

Hampshire.

After the plaintiffs brought suit, the defendants moved for

summary judgment, arguing that they are immune from liability

under the recreational use statutes, RSA 508:14, I, RSA 212:34,

Page 1

Kenis085

I, and RSA 215-A:34, II. The trial court granted the defendants'

motion. This appeal followed.

When reviewing a trial court's grant of summary judgment, we

consider the affidavits and other evidence, and all inferences

properly drawn from them, in the light most favorable to the non-

moving party. Estate of Joshua T. v. State, 150 N.H. 405, 407

(2003). If our review of the evidence does not reveal any

genuine issue of material fact, and if the moving party is

entitled to judgment as a matter of law, we will affirm the trial

court's decision. Id.

On appeal, the plaintiffs first argue that the defendants

are not immune from liability because they do not qualify as

owners, lessees or occupants of land. Because we agree, we need

not address the plaintiffs' other arguments on appeal.

RSA 508:14, I, provides:

An owner, occupant, or lessee of land, including

the state or any political subdivision, who without

charge permits any person to use land for recreational

purposes or as a spectator of recreational activity,

shall not be liable for personal injury or property

damage in the absence of intentionally caused injury or

damage.

RSA 212:34 provides, in pertinent part:

I. An owner, lessee or occupant of premises owes

no duty of care to keep such premises safe for entry or

use by others for hunting, fishing, trapping, camping,

water sports, winter sports or OHRVs as defined in RSA

215-A, hiking, sightseeing, or removal of fuelwood, or

to give any warning of hazardous conditions, uses of,

structures, or activities on such premises to persons

entering for such purposes, except as provided in

paragraph III hereof.

II. An owner, lessee or occupant of premises who

gives permission to another to hunt, fish, trap, camp,

hike, use OHRVs as defined in RSA 215-A, sightsee upon,

or remove fuelwood from, such premises . . . does not

thereby:

(a) Extend any assurance that the premises are

safe for such

purpose, or

(b) Constitute the person to whom permission

has been

granted the legal status of an invitee to whom a

duty of care is

owed, or

(c) Assume responsibility for or incur

liability for an injury to

person or property caused by any act of such person

to whom

permission has been granted except as provided in

paragraph III

hereof.

RSA 215-A:34, II provides, in pertinent part:

It is recognized that OHRV operation may be

Page 2

Kenis085

hazardous. Therefore, each person who drives or rides

an OHRV accepts, as a matter of law, the dangers

inherent in the sport, and shall not maintain an action

against an owner, occupant, or lessee of land for any

injuries which result from such inherent risks,

dangers, or hazards.

The issue before us presents questions of statutory

interpretation. We are the final arbiter of the intent of the

legislature as expressed in the words of the statute considered

as a whole. In the Matter of Jacobson & Tierney, 150 N.H. 513,

515 (2004). We first examine the language of the statute, and,

where possible, we ascribe the plain and ordinary meanings to the

words used. Id. We review the trial court's interpretation of a

statute de novo. Remington Invs. v. Howard, 150 N.H. 653, 654

(2004).

For the purposes of the above statutes, the parties agree

that a snowmobile qualifies as an off-highway recreational

vehicle (OHRV), see RSA 215-A:1, VI (2000). Under RSA 508:14, I,

RSA 212:34, and RSA 215-A:34, II, immunity from liability is

provided to a party who is an owner, lessee or occupant of the

land where the accident occurred. The parties agree that the

defendants were not owners or lessees of the land. Thus, for the

defendants to be entitled to immunity under any of the three

recreational use statutes, they must have been occupants of the

land.

None of the recreational use statutes provides a definition

of "occupant." When statutory terms are undefined, we ascribe

to them their plain and ordinary meaning. In the Matter of

Blanchflower & Blanchflower, 150 N.H. 226, 227 (2003). Webster's

dictionary defines "occupant" in several different ways,

including: (1) "one who takes the first possession of something

that has no owner and thereby acquires title by occupancy"; (2)

"one who takes possession under title, lease or tenancy at

will"; (3) "one who occupies a particular place or premises";

and (4) "one who has actual use or possession of something."

Webster's Third New International Dictionary 1560 (2d unabridged

ed. 2002). Black's Law Dictionary defines "occupant" as either

"[o]ne who has possessory rights in, or control over, certain

property or premises" or "[o]ne who acquires title by

occupancy." Black's Law Dictionary 1106 (7th ed. 1999). These

varying definitions demonstrate that the term "occupant" has

the potential to encompass either a broad or a narrow class of

persons depending upon the context in which the term is used. An

"occupant" could be someone who is on the premises, someone who

is using the premises, someone who has control of the premises,

someone who has a possessory interest in the premises, or someone

who has title to the premises.

The defendants refer us to Smith v. Sno Eagles Snowmobile

Club, Inc., 823 F.2d 1193, 1197-98 (7th Cir. 1987) (construction

approved by Wisconsin intermediate appellate court in Hall v.

Turtle Lake Lions Club, 531 N.W.2d 636 (1988)), in which the

Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, interpreting a similar

Wisconsin statute, determined that a snowmobile club qualified as

an occupant because it made actual use of the property with a

degree of permanence. But see Ward v. State, 890 P.2d 1144,

1147-48 (Ariz. 1995) (rejecting Seventh Circuit's interpretation

and concluding that "occupant" must have ability to exclude

persons from land or grant persons access to land). The

defendants argue that we should interpret the New Hampshire

recreational use statutes using this definition of "occupant."

But, in arguing that we follow Smith, the defendants overlook a

key difference between our policy of interpreting recreational

use statutes and the policy employed by Wisconsin courts. We

follow the policy of strictly interpreting statutes that are in

Page 3

Kenis085

derogation of the common law, Sweeney v. Ragged Mt. Ski Area, 151

N.H. 239, 241 (2004); Wisconsin courts do not. See Leu v. Price

County Snowmobile Trails Association, Inc., 695 N.W.2d 889, 893

n.6 (Wis. Ct. App. 2005) (noting that Wisconsin courts construe

recreational use statutes granting immunity liberally).

Our goal is to apply statutes in light of the legislature's

intent in enacting them, and in light of the policy sought to be

advanced by the entire statutory scheme. State v. Whittey, 149

N.H. 463, 467 (2003). When we interpret statutes that deal with

the same subject matter, we consider all of the statutes when

interpreting any one of them. See Berksdale v. Town of Epsom,

136 N.H. 511, 515-16 (1992). Although we look to the plain and

ordinary meaning of the statutory language to determine

legislative intent, we will not read words or phrases in

isolation; we read them in the context of the entire statute.

Franklin v. Town of Newport, 151 N.H. 508, 509 (2004).

RSA 508:14, I, expressly states that immunity shall apply to

"[an] owner, occupant, or lessee of land . . . who without

charge permits any person to use land for recreational purposes .

. . ." (Emphasis added.) RSA 212:34, I, provides that an

owner, lessee or occupant of premises owes no duty of care, while

RSA 212:34, II makes it clear that if that owner, lessee or

occupant gives permission to another to use the land, that

permission shall not, under certain circumstances, create a duty

of care under RSA 212:34, I. Thus, by implication, an owner,

occupant or lessee is one who has the ability or authority to

grant permission to use land. Though RSA 215-A:34, II contains

no language specifically referencing permission, it uses the same

terms as RSA 212:34 or RSA 508:14; i.e., owner, occupant or

lessee of land. Further, no different purpose is apparent from

the statute; rather, it simply gives more detail about an

owner's, occupant's, or lessee's potential immunity regarding

OHRVs. As we noted in a different context in Estate of Gordon-

Couture v. Brown, the model recreational use statute (drafted by

the Committee of State Officials on Suggested State Legislation

of the Council of State Governments), which shares much in common

with the New Hampshire recreational use statutes, "expressed a

basic quid pro quo in its declaration of policy, namely,

permission to the general public to use private land for

recreational purposes in exchange for immunity from liability for

resulting injuries." Estate of Gordon-Couture v. Brown, 152

N.H. ___, ___ (decided May 23, 2005) (quotation omitted; emphasis

added).

By suggesting that we adopt an interpretation of

"occupant" that includes persons who do not have the ability or

authority to permit access to land, the defendants overlook the

statutory language and our policy of strictly interpreting

statutes in derogation of the common law. For these reasons, we

hold that an occupant of land must, at least, have the ability or

authority to give persons permission to enter or use land.

The defendants also rely upon Kantner v. Combustion

Engineering, 701 F. Supp. 943 (D.N.H. 1988). While Kantner may

have ruled that defendants without the apparent ability or

authority to permit access to land were entitled to immunity,

Kantner did not specifically address whether permission is a

required element of the New Hampshire recreational use statutes.

More importantly, Kantner relied upon the broad definition of

"occupant" set forth in Smith. Kantner, 701 F. Supp. at 947.

As we rejected that definition above, we do not find Kantner

persuasive.

The defendants also refer to our memorandum decision in

Page 4

Kenis085

Fanny v. Pike Industries, Inc., 119 N.H. 108 (1979), in which we

upheld the grant of immunity to a general contractor who was an

occupant of land. The defendants point out that our opinion in

Fanny contains little factual detail and includes no discussion

of the general contractor's ability or authority to permit a

person's entry onto the land. Fanny, 119 N.H. at 108-09.

Further, neither party in Fanny appears to have argued that the

general contractor's ability or authority, or lack thereof, to

permit persons access to the land was a factor to be considered

when interpreting the term "occupant." Id. Thus, we do not

find Fanny helpful to this case. To the extent that it can be

read to hold that an "occupant" need not have the ability or

authority to give persons permission to enter or use land, it is

hereby overruled.

The defendants further argue that interpreting the term

"occupant" to require the ability or authority to permit access

to land would make the term "occupant" "virtually

indistinguishable from the term 'owner,' and, thus, render the

legislature's use of the term 'occupant' meaningless." We

disagree.

The language of RSA 508:14, I, demonstrates that the

legislature contemplated that there will be occupants who have

the ability or authority to permit persons onto land. As

discussed above, RSA 508:14, I, applies to: "An owner,

occupant, or lessee of land, including the state or any political

subdivision, who without charge permits any person to use land

for recreational purposes." (Emphasis added.) The legislature

must have contemplated at least some occupants, other than owners

or lessees, who have the ability or authority to permit persons

onto land. Such occupants might include a contractor who has

responsibility for access to land and maintenance of a project

site or an organization that manages a city-owned swimming pool

and has the ability to permit or deny access to the land, see

Ward, 890 P.2d at 1148, or a spouse who resides on land but does

not hold title to that land. Thus, we do not find the

defendants' argument persuasive.

The defendants also argue that interpreting the statute so

as not to include snow groomers would be inconsistent with the

purpose of the statute - to make more land available for

recreational uses. The defendants argue that without snow

groomers, the "snowmobile trails would not be available for

public use" because, presumably, such land, though accessible,

would not be usable by snowmobiles. We disagree with the

defendants' argument that our interpretation is inconsistent with

the purpose of the statute.

While a statute may abolish a common law right, there is a

presumption that the legislature has no such purpose. Sweeney,

151 N.H. at 241. If such a right is to be taken away, it must be

expressed clearly by the legislature. Id. As stated above,

these immunity provisions are strictly construed. Id. The only

purpose clearly expressed in the statutes is the purpose to

encourage persons to permit people to enter their land for

recreational uses. That purpose is fully served by our holding

in this case. The activities of snow groomers may facilitate the

use of land for certain recreational uses such as snowmobiling,

but the statutes, strictly construed, are intended to immunize

those who permit access to land, not those who simply facilitate

its use after permission has been granted.

Because we conclude that, in order to qualify for immunity

under the recreational use statutes, one must at least have the

ability or authority to permit persons to use or enter the land,

the defendants are not occupants for the purposes of the

recreational use statutes. The defendants had neither the

Page 5

Kenis085

ability nor the authority to make land available for recreational

purposes in the manner contemplated by the legislature; rather,

they merely had the ability and authority to make that land more

easily usable than it might otherwise be for recreational

purposes.

Reversed and remanded.

BRODERICK, C.J., and NADEAU, DUGGAN and GALWAY, JJ.,

concurred.

Page 6

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- TownsendDokument10 SeitenTownsendChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- SchulzDokument9 SeitenSchulzChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- C C B J.D./M.B.A.: Hristopher - UckDokument2 SeitenC C B J.D./M.B.A.: Hristopher - UckChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- BallDokument6 SeitenBallChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- JK S RealtyDokument12 SeitenJK S RealtyChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Om Ear ADokument12 SeitenOm Ear AChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Great American InsuranceDokument9 SeitenGreat American InsuranceChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- MoussaDokument19 SeitenMoussaChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- HollenbeckDokument14 SeitenHollenbeckChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- BondDokument7 SeitenBondChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Claus OnDokument12 SeitenClaus OnChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- City ConcordDokument17 SeitenCity ConcordChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- FranchiDokument7 SeitenFranchiChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- AtkinsonDokument8 SeitenAtkinsonChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- MooreDokument4 SeitenMooreChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- NicholsonDokument4 SeitenNicholsonChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philip MorrisDokument8 SeitenPhilip MorrisChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ba Kun Czy KDokument3 SeitenBa Kun Czy KChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barking DogDokument7 SeitenBarking DogChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- DaviesDokument6 SeitenDaviesChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Al WardtDokument10 SeitenAl WardtChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reporter@courts - State.nh - Us: The Record Supports The Following FactsDokument6 SeitenReporter@courts - State.nh - Us: The Record Supports The Following FactsChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- PoulinDokument5 SeitenPoulinChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- JefferyDokument7 SeitenJefferyChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- MarchandDokument9 SeitenMarchandChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dil BoyDokument8 SeitenDil BoyChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reporter@courts State NH UsDokument21 SeitenReporter@courts State NH UsChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lebanon HangarDokument8 SeitenLebanon HangarChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pha NeufDokument9 SeitenPha NeufChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boso Net ToDokument9 SeitenBoso Net ToChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- 10 Temporary Restraining OrderDokument5 Seiten10 Temporary Restraining OrderGuy Hamilton-SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angara Vs Electoral Commission DigestDokument1 SeiteAngara Vs Electoral Commission DigestGary Egay0% (1)

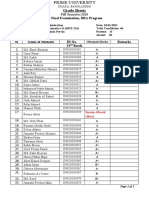

- Grade Sheet S: Final Examination, BBA ProgramDokument2 SeitenGrade Sheet S: Final Examination, BBA ProgramRakib Hasan NirobNoch keine Bewertungen

- cs14 2013Dokument3 Seitencs14 2013stephin k jNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basics of Legislation ProjectDokument21 SeitenBasics of Legislation ProjectJayantNoch keine Bewertungen

- PEPSI Cola Vs TanauanDokument2 SeitenPEPSI Cola Vs TanauanJimNoch keine Bewertungen

- IMS, University of Lucknow: Research Paper Business CommunicationDokument15 SeitenIMS, University of Lucknow: Research Paper Business CommunicationAnisha RajputNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rural Bank of Salinas V CADokument2 SeitenRural Bank of Salinas V CAmitsudayo_100% (2)

- 2 Muskrat Vs United StatesDokument1 Seite2 Muskrat Vs United StatesVanityHughNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cat Smith ManifestoDokument6 SeitenCat Smith Manifestoapi-3724768Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rhema International Livelihood Foundation, Inc., Et Al., v. Hibix, Inc. G.R. Nos. 225353-54, August 28, 2019Dokument2 SeitenRhema International Livelihood Foundation, Inc., Et Al., v. Hibix, Inc. G.R. Nos. 225353-54, August 28, 2019Kristel Alyssa MarananNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitutional Law Essay OneDokument8 SeitenConstitutional Law Essay OneshizukababyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jeanette Runyon - Respod of The Office of The Prosecutor General of Ukraine PDFDokument2 SeitenJeanette Runyon - Respod of The Office of The Prosecutor General of Ukraine PDFMyRed BootsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proposed Rule: Airworthiness Directives: Cirrus Design Corp. Models SR20 and SR22 AirplanesDokument2 SeitenProposed Rule: Airworthiness Directives: Cirrus Design Corp. Models SR20 and SR22 AirplanesJustia.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anser Key For Class 8 Social Science SA 2 PDFDokument5 SeitenAnser Key For Class 8 Social Science SA 2 PDFSoumitraBagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Articles of Confederation SimulationDokument7 SeitenArticles of Confederation Simulationapi-368121935100% (1)

- Estrada Vs Escritor 2 RevisedDokument4 SeitenEstrada Vs Escritor 2 RevisedJackie CanlasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minutes of The Meeting: Issues and ConcernsDokument5 SeitenMinutes of The Meeting: Issues and ConcernsBplo CaloocanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02 PSIR MAins 2019 Shubhra RanjanDokument9 Seiten02 PSIR MAins 2019 Shubhra Ranjanhard020% (1)

- Distributive JusticeDokument8 SeitenDistributive JusticethomasrblNoch keine Bewertungen

- "The German New Order in Poland" by The Polish Ministry of Information, 1941Dokument97 Seiten"The German New Order in Poland" by The Polish Ministry of Information, 1941Richard TylmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contract Tutorial Preparation 4Dokument4 SeitenContract Tutorial Preparation 4Saravanan Rasaya0% (1)

- Legislative Department Case DigestDokument10 SeitenLegislative Department Case DigestiyangtotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agent Orange CaseDokument165 SeitenAgent Orange CaseזנוביהחרבNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 5 Political History of PakistanDokument33 SeitenLecture 5 Political History of PakistanAFZAL MUGHALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Holman Et Al v. Apple, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 86Dokument2 SeitenHolman Et Al v. Apple, Inc. Et Al - Document No. 86Justia.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judicial Precedent As A Source of LawDokument8 SeitenJudicial Precedent As A Source of LawBilawal MughalNoch keine Bewertungen

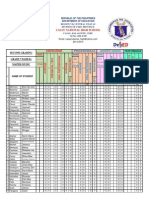

- Casay NHS K12 Grading TemplateDokument4 SeitenCasay NHS K12 Grading TemplatePrince Yahwe RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- QC MAPAPA Elementary (Public)Dokument11 SeitenQC MAPAPA Elementary (Public)Gabriel SalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Research Writing Syllabus FinalDokument5 SeitenLegal Research Writing Syllabus Finalremil badolesNoch keine Bewertungen