Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Gonza 124

Hochgeladen von

Chris BuckOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Gonza 124

Hochgeladen von

Chris BuckCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Gonza124

NOTICE: This opinion is subject to motions for rehearing under

Rule 22 as well as formal revision before publication in the New

Hampshire Reports. Readers are requested to notify the Reporter,

Supreme Court of New Hampshire, One Noble Drive, Concord, New

Hampshire 03301, of any editorial errors in order that

corrections may be made before the opinion goes to press. Errors

may be reported by E-mail at the following address:

reporter@courts.state.nh.us. Opinions are available on the

Internet by 9:00 a.m. on the morning of their release. The direct

address of the court's home page is:

http://www.courts.state.nh.us/supreme.

THE SUPREME COURT OF NEW HAMPSHIRE

___________________________

Hillsborough-southern judicial district

No. 2002-474

THE STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE

v.

RUBEN GONZALEZ

Argued: July 10, 2003

Opinion Issued: September 30, 2003

Peter W. Heed, attorney general (Karen E. Huntress,

assistant attorney general, on the brief and orally), for the

State.

Dawnangela Minton, assistant appellate defender, of Concord,

by brief and orally, for the defendant.

DUGGAN, J. The defendant, Ruben Gonzalez, was convicted

after a jury trial in Superior Court (Hicks, J.) of three counts

of aggravated felonious sexual assault, see RSA 632-A:2 (Supp.

2002), two counts of felonious sexual assault, see RSA 632-A:3

(Supp. 2002), and two counts of misdemeanor sexual assault, see

RSA 632-A:4 (1996). The victim was the defendant's stepdaughter,

who was eight years old when the assaults began. We affirm.

On appeal, the defendant argues that the trial court erred

when it admitted testimony from two lay witnesses regarding the

tendency of victims to

fail to contemporaneously report abuse and the tendency of

victims to recant or deny abuse.

At trial, the State's first witness was Kris Geno, a New

Hampshire Division for Children, Youth and Families social

worker. The State questioned Geno as to whether she had

"received any training and education relative to specifically

dealing with allegations of sexual abuse." Geno testified that

she had received training on interviewing sexual abuse victims,

victim recantations, and dealing with different types of sexual

offenders. The State asked Geno about the frequency of victim

recantations or denials. Geno testified that denials or

recantations were not unusual.

Detective Brooke Lemoine also testified at trial. After

eliciting testimony from him regarding his training and

experience, the prosecutor asked, "In your experience with your

caseload, are sexual assaults reported contemporaneous with the

abuse?" Lemoine testified that contemporaneous disclosure of

Page 1

Gonza124

sexual abuse is unusual.

The defendant argues that this testimony was inadmissible.

The State argues that the defendant failed to preserve the issue

of the admissibility of Geno's testimony because he failed to

make a timely objection. In the alternative, the State argues

that Geno's and Lemoine's testimony was admissible lay witness

testimony because it was based upon their perceptions and not

specialized training. The State further argues that, even if the

testimony was inadmissible, the error was harmless.

We first address the State's argument that the defendant

failed to preserve the issue of Geno's testimony for our review.

The defendant first objected when the State asked Geno whether

she "received any training and education relative to

specifically dealing with allegations of sexual abuse?" During

the bench conference, the prosecutor offered that the reason she

was "asking [Geno] for her education and her training

background, and what she has done specifically in her caseload,

is because I intend to ask her about recantations and denials."

In response, defense counsel further objected stating that "the

offer of proof's been made [that the prosecutor's] gonna [sic]

ask about recantations and denials. That is expert testimony.

There was - you know, there was no expert testimony noticed up.

That is absolutely inappropriate." The trial judge noted that

defense counsel was objecting to the prosecution's anticipated

question regarding Geno's experience with recantations and

denials and permitted the anticipated question over the

defendant's objection.

The State then asked Geno, "In your experience, are denials

or recantations unusual?" Defense counsel did not object to

this question. Geno answered, "No." Next, the State asked

Geno: "In your experience, why or why not?" Defense counsel

immediately objected. At the bench conference, the defendant

again raised his objection that Geno's testimony constituted

expert testimony, requiring that she be qualified as an expert.

This time the trial court sustained the objection.

"The general rule in New Hampshire is that a

contemporaneous and specific objection is required to preserve an

issue for appellate review." State v. Searles, 141 N.H. 224,

230 (1996) (quotation omitted). In State v. Bouchard, 138 N.H.

581, 584 (1994), we held that the defendant's oral motion on the

day of trial to exclude certain evidence was adequate to preserve

the issue, thus making a contemporaneous objection at trial

unnecessary. The oral motion served the purpose of the

contemporaneous objection requirement by allowing the trial court

the opportunity to correct any claimed errors. State v. Mello,

137 N.H. 597, 600 (1993).

At the bench conference that occurred before Geno's

testimony was admitted, defense counsel anticipated that after

asking Geno about her training and education, the prosecutor

would then ask her about recantations and denials and that this

would constitute inadmissible expert testimony. In addition, the

trial judge acknowledged that defense counsel was objecting to

the anticipated question and ruled accordingly. This objection,

like the oral motion in Bouchard, adequately preserved the issue

even though the objection was made before the pertinent question

was asked. Bouchard, 138 N.H. at 584. Defense counsel stated

the specific basis for the objection and gave the trial court the

opportunity to correct any claimed errors. Mello, 137 N.H. at

600. We conclude this objection adequately preserved the issue

of the admissibility of Geno's testimony.

We next consider whether the trial court erroneously

admitted Geno's testimony regarding victim recantations. We

Page 2

Gonza124

review the ruling to determine whether it was an unsustainable

exercise of discretion. See State v. Lambert, 147 N.H. 295, 296

(2001). We will reverse the trial court "only if the appealing

party can demonstrate that the ruling was untenable or

unreasonable and that the error prejudiced the party's case."

State v. Searles, 141 N.H. 224, 227 (1996) (quotation omitted).

The question of the admissibility turns on the

characterization of Geno's testimony. Expert testimony involves

"matters of scientific, mechanical, professional or other like

nature, which requires special study, experience, or observation

not within the common knowledge of the general public." State

v. Martin, 142 N.H. 63, 65 (1997) (quotation omitted). Lay

testimony must be confined to "personal observations which any

lay person would be capable of making." Id. (brackets and

quotation omitted). If Geno's testimony is expert testimony,

then it was not properly admitted as lay testimony. See id. at

66; accord Sample v. State, 643 So. 2d 524, 529-30 (Miss. 1994)

(plurality opinion) (stating that testimony must be considered

expert testimony if in order to testify, "the witness must

possess some experience or expertise beyond that of the average,

randomly selected adult"). If Geno's testimony is not expert

testimony, then it must be determined whether it is permissible

lay testimony. See N.H. R. Ev. 602, 701. Because Geno's

testimony regarding victim recantations is expert testimony, it

was erroneously admitted as lay testimony.

This case is similar to the testimony at issue in State v.

Martin, 142 N.H. 63 (1997). In Martin, a sexual assault victim's

treating physician testified to the physical condition of the

victim based on the physician's personal observations during an

internal gynecological examination. See Martin, 142 N.H. at 66.

In determining whether this testimony should be treated as expert

testimony, we stated that: "The focus is not solely on whether a

professional speaks from personal observation, but also whether

the personal observations require specialized skills not within

the ken of the ordinary person." Id. We also explained that

lay testimony must be confined to "personal observations which

any lay person would be capable of making" and is improperly

admitted when it goes "beyond mere observation and require[s]

professional training not possessed by the public at large."

Id. at 65-66 (brackets and quotation omitted). While in Martin

the State argued that the physician's testimony was not expert

testimony because it involved personal or first-hand knowledge

based on her experience, we held that it was expert testimony

because the observations and findings "required special skills

and knowledge not possessed by the average layperson." Id. at

66-67; see Seal v. Miller, 605 So. 2d 240, 244 (Miss. 1992)

(holding that police officer's testimony based on experience

investigating accidents is not lay testimony).

The testimony at issue in the present case involved whether,

in sexual abuse cases, victim denials and recantations were not

unusual. The tendency or frequency of sexual abuse victims'

denials and recantations are not observations that any layperson

is capable of making, but rather require special experience and

knowledge not possessed by the public at large. We have

recognized that a layperson is not capable of making such

observations because "a child's delayed disclosure of abuse,

inconsistent statements about abuse, and recantation of

statements about abuse, may be puzzling or appear

counterintuitive to lay observers when they consider the

suffering endured by a child who is continually being abused."

State v. Cressey, 137 N.H. 402, 411 (1993). Because of its

counterintuitive nature, expert testimony may be permitted to

educate the jury about apparent inconsistent behavior by a victim

following an assault and to "provid[e] useful information that

is beyond the common experience of an average juror." State v.

Page 3

Gonza124

MacRae, 141 N.H. 106, 109 (1996).

Here, Geno testified that, in sexual abuse cases, victim

denial or recantations are not unusual. As a social worker, she

was trained in interviewing sexual abuse victims and dealing with

recantations. Geno's employment and training provided her with

specialized knowledge and experience not available to the general

public about the frequency of victim denials and recantations.

While her testimony is based upon her personal experience with

sexual abuse cases, her conclusion that victim denials are not

unusual is based upon her training, experience, and observations

that are not within the common knowledge of the general public

and are beyond the common experience of an average juror. See

Martin, 142 N.H. at 65; MacRae, 141 N.H. at 109. Because Geno's

testimony regarding victim denials and recantations required

specialized knowledge and experience, we conclude that it was not

properly admitted lay testimony.

For the same reason, we conclude that the trial court

erroneously admitted Lemoine's testimony. Lemoine testified that

he was trained to interview child victims of sexual abuse. He

testified that he attended "advanced interviewing technique

schools, to enable me to better work these types of

investigations." Lemoine testified that, in more than four

years, he has served as the lead investigator on at least

seventy-four sexual assault cases. Lemoine further testified

that it is not unusual for a sexual assault victim to delay

disclosure.

Like Geno, Lemoine received training and had experience with

sexual assault victims not possessed by the public at large.

While Lemoine's testimony was based upon his personal

observations while investigating sexual assault cases, his

observations and conclusions regarding the frequency of delayed

disclosures required specialized training, experience and skill

"not within the ken of the ordinary person." Martin, 142 N.H.

at 66. Geno's and Lemoine's testimony regarding "the delayed

reporting of abuse, inconsistent recountings of the abuse, and

recantation of the initial disclosure" is expert testimony and

inadmissible as lay witness testimony. State v. Chamberlain, 137

N.H. 414, 417 (1993).

Finally, we consider whether the admission of Geno's and

Lemoine's testimony constituted harmless error. "The burden to

establish [harmless error] lies with the State." State v.

Reynolds, 136 N.H. 325, 327 (1992). That burden is "satisfied

by proof beyond a reasonable doubt that the erroneously admitted

evidence did not affect the verdict." State v. Thibedau, 142

N.H. 325, 329 (1997). In deciding whether the State has met its

burden, we consider the strength of the alternative evidence

presented at trial, and the character of the inadmissible

evidence, including whether the evidence was cumulative or

inconsequential. State v. Hodgdon, 143 N.H. 399, 401-02 (1999).

Here, as in State v. Lemieux, 136 N.H. 329, 331-32 (1992),

"the evidence most damaging to the defendant was the victim's

description, in vivid detail, of the various sexual acts." The

victim, who was seventeen years old by the time of trial, was

able to remember the details of assaults that occurred up to nine

years earlier. She testified that the first assault occurred in

the fall of 1992 when the defendant touched her breasts while she

was showering. According to the victim, she was ten years old

when the defendant assaulted her in the bathroom again. The

defendant entered the bathroom as the victim was brushing her

hair wearing only a towel. He turned her around, picked her up,

sat her on the sink, unzipped his pants, took out his penis, and

started rubbing it against her vagina. The victim also testified

that the defendant licked her vagina in her bedroom when she was

Page 4

Gonza124

twelve years old. The victim further testified that while she

was in her mother's bedroom watching a movie, the defendant

entered, pushed her onto the bed when she attempted to leave,

touched her breasts, kissed her lips, pulled his pants down to

his ankles, masturbated and had intercourse with her.

She also testified that when she was thirteen, the defendant

yelled at her for having boys in her bedroom. At that time, the

defendant touched her breasts over her shirt. The victim

testified that the last assault occurred at the Red Roof Inn,

where the family lived after a fire destroyed their apartment.

She testified that she entered the room the defendant shared with

her mother and brothers to get a drink when the defendant touched

her breasts over her clothing.

The victim's sister, Kim, testified that on January 22,

1997, the victim came into her bedroom and told her that the

defendant "was touching her." Kim testified that in late

December 1997, she attended a meeting with the victim, the

victim's mother, the defendant and the defendant's brother and

sister-in-law. At the family meeting, the defendant apologized

and "said it wouldn't happen again." Given the defendant's

admission and the victim's detailed accounts of the assaults, we

conclude that Geno's and Lemoine's inadmissible lay testimony was

inconsequential, and thus the error was harmless. Lemieux, 136

N.H. at 332.

Affirmed.

NADEAU and DALIANIS, JJ., concurred.

Page 5

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- JK S RealtyDokument12 SeitenJK S RealtyChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- SchulzDokument9 SeitenSchulzChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- C C B J.D./M.B.A.: Hristopher - UckDokument2 SeitenC C B J.D./M.B.A.: Hristopher - UckChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Claus OnDokument12 SeitenClaus OnChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Great American InsuranceDokument9 SeitenGreat American InsuranceChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- TownsendDokument10 SeitenTownsendChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- BondDokument7 SeitenBondChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- NicholsonDokument4 SeitenNicholsonChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- BallDokument6 SeitenBallChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- MoussaDokument19 SeitenMoussaChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- MooreDokument4 SeitenMooreChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- City ConcordDokument17 SeitenCity ConcordChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Om Ear ADokument12 SeitenOm Ear AChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- HollenbeckDokument14 SeitenHollenbeckChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Al WardtDokument10 SeitenAl WardtChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- DaviesDokument6 SeitenDaviesChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- AtkinsonDokument8 SeitenAtkinsonChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philip MorrisDokument8 SeitenPhilip MorrisChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Reporter@courts - State.nh - Us: The Record Supports The Following FactsDokument6 SeitenReporter@courts - State.nh - Us: The Record Supports The Following FactsChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ba Kun Czy KDokument3 SeitenBa Kun Czy KChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Reporter@courts State NH UsDokument21 SeitenReporter@courts State NH UsChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barking DogDokument7 SeitenBarking DogChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- JefferyDokument7 SeitenJefferyChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- FranchiDokument7 SeitenFranchiChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Dil BoyDokument8 SeitenDil BoyChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pha NeufDokument9 SeitenPha NeufChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- PoulinDokument5 SeitenPoulinChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- MarchandDokument9 SeitenMarchandChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Boso Net ToDokument9 SeitenBoso Net ToChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lebanon HangarDokument8 SeitenLebanon HangarChris BuckNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Derridean Différance - UsiefDokument16 SeitenOn Derridean Différance - UsiefS JEROME 2070505Noch keine Bewertungen

- Plaza 66 Tower 2 Structural Design ChallengesDokument13 SeitenPlaza 66 Tower 2 Structural Design ChallengessrvshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organization and Management Module 3: Quarter 1 - Week 3Dokument15 SeitenOrganization and Management Module 3: Quarter 1 - Week 3juvelyn luegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 7 Sex Limited InfluencedDokument19 SeitenWeek 7 Sex Limited InfluencedLorelyn VillamorNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Construction of Optimal Portfolio Using Sharpe's Single Index Model - An Empirical Study On Nifty Metal IndexDokument9 SeitenThe Construction of Optimal Portfolio Using Sharpe's Single Index Model - An Empirical Study On Nifty Metal IndexRevanKumarBattuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proceeding of Rasce 2015Dokument245 SeitenProceeding of Rasce 2015Alex ChristopherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shostack ModSec08 Experiences Threat Modeling at MicrosoftDokument11 SeitenShostack ModSec08 Experiences Threat Modeling at MicrosoftwolfenicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Borang Ambulans CallDokument2 SeitenBorang Ambulans Callleo89azman100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- OZO Player SDK User Guide 1.2.1Dokument16 SeitenOZO Player SDK User Guide 1.2.1aryan9411Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fss Presentation Slide GoDokument13 SeitenFss Presentation Slide GoReinoso GreiskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Partes de La Fascia Opteva Y MODULOSDokument182 SeitenPartes de La Fascia Opteva Y MODULOSJuan De la RivaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5c3f1a8b262ec7a Ek PDFDokument5 Seiten5c3f1a8b262ec7a Ek PDFIsmet HizyoluNoch keine Bewertungen

- PR KehumasanDokument14 SeitenPR KehumasanImamNoch keine Bewertungen

- 74HC00D 74HC00D 74HC00D 74HC00D: CMOS Digital Integrated Circuits Silicon MonolithicDokument8 Seiten74HC00D 74HC00D 74HC00D 74HC00D: CMOS Digital Integrated Circuits Silicon MonolithicAssistec TecNoch keine Bewertungen

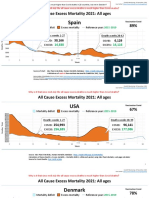

- Countries EXCESS DEATHS All Ages - 15nov2021Dokument21 SeitenCountries EXCESS DEATHS All Ages - 15nov2021robaksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDokument63 SeitenChapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDr. Shuva GhoshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecturenotes Data MiningDokument23 SeitenLecturenotes Data Miningtanyah LloydNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blue Prism Data Sheet - Provisioning A Blue Prism Database ServerDokument5 SeitenBlue Prism Data Sheet - Provisioning A Blue Prism Database Serverreddy_vemula_praveenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specificities of The Terminology in AfricaDokument2 SeitenSpecificities of The Terminology in Africapaddy100% (1)

- Equivalent Fractions Activity PlanDokument6 SeitenEquivalent Fractions Activity Planapi-439333272Noch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Personal Finance Towards Managing of Money - DraftaDokument35 SeitenRole of Personal Finance Towards Managing of Money - DraftaAndrea Denise Lion100% (1)

- B.SC BOTANY Semester 5-6 Syllabus June 2013Dokument33 SeitenB.SC BOTANY Semester 5-6 Syllabus June 2013Barnali DuttaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 5 Designing and Developing Social AdvocacyDokument27 SeitenLesson 5 Designing and Developing Social Advocacydaniel loberizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dialogue Au Restaurant, Clients Et ServeurDokument9 SeitenDialogue Au Restaurant, Clients Et ServeurbanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Regions of Alaska PresentationDokument15 SeitenRegions of Alaska Presentationapi-260890532Noch keine Bewertungen

- What Is TranslationDokument3 SeitenWhat Is TranslationSanskriti MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Homework Song FunnyDokument5 SeitenThe Homework Song Funnyers57e8s100% (1)

- Dtu Placement BrouchureDokument25 SeitenDtu Placement BrouchureAbhishek KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anatomy Anal CanalDokument14 SeitenAnatomy Anal CanalBela Ronaldoe100% (1)

- Week 7Dokument24 SeitenWeek 7Priyank PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadVon EverandThe Art of Fact Investigation: Creative Thinking in the Age of Information OverloadBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Litigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessVon EverandLitigation Story: How to Survive and Thrive Through the Litigation ProcessBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Busted!: Drug War Survival Skills and True Dope DVon EverandBusted!: Drug War Survival Skills and True Dope DBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (7)

- Strategic Positioning: The Litigant and the Mandated ClientVon EverandStrategic Positioning: The Litigant and the Mandated ClientBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Greed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsuranceVon EverandGreed on Trial: Doctors and Patients Unite to Fight Big InsuranceNoch keine Bewertungen