Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Logophobia in Jane Eyre

Hochgeladen von

Wiem BelkhiriaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Logophobia in Jane Eyre

Hochgeladen von

Wiem BelkhiriaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

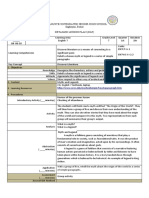

Logophobia in "Jane Eyre"

Author(s): Randall Craig

Source: The Journal of Narrative Technique, Vol. 23, No. 2 (Spring, 1993), pp. 92-113

Published by: Journal of Narrative Theory

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30225382

Accessed: 16-09-2016 09:11 UTC

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted

digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about

JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

http://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of Narrative Theory is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Narrative Technique

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre

Randall Craig

On the night before her wedding is to take place, Jane Eyre is troubled by a sense

of foreboding, as she later explains to Rochester:

I continued in dreams the idea of a dark and gusty night. I continued also the

wish to be with you, and experienced a strange, regretful consciousness of

some barrier dividing us. ... I thought, sir, that you were on the road a long

way before me; and I strained every nerve to overtake you, and made effort

on effort to utter your name and entreat you to stop-but my movements were

fettered, and my voice still died away inarticulate. (309)1

She, of course, cannot know that this oneiric barrier takes the corporeal form of a

Mrs. Rochester currently residing at Thornfield. Were Mr. Rochester to be believed,

his existing marriage to Bertha is nothing more than "an obstacle of custom-a mere

conventional impediment" (247). But Jane's nightmare of inarticulate desire

suggests that more is at stake here than social proprieties, as he seems to believe, or

even ethical norms, such as she grapples with after learning Rochester's uxorial

secret. Another problem and an ineradicable one confronts the lovers: the nature and

(mis)uses of language itself. When she most needs it, Jane is afraid that her voice

will fail her, and throughout Jane Eyre speakers have good reason for concern about

the medium they employ.

Fears about language use take two quite different forms, depending upon whether

it is believed that words are too weak to serve human needs or that human needs are

too frail to survive verbal expression. The former inclination produces a kind of

linguistic skepticism whose nature varies from the conviction that language is

inherently unequal to the demands placed upon it (ontological fear), to the belief that

words are readily misused by mendacious speakers and that such duplicity is

virtually undetectable (pragmatic fear), to the concern that telling one's story

inevitably invokes the irreconcilable claims of truth and plausibility (narrative fear).

The ontological fear of language raises the possibility that experience and articulation are incompatible by nature. Words may fail speakers at any time, not only at

moments of emotional intensity such as those depicted in Jane's nightmare. A less

radical notion is that love and language are at odds in practice rather than in

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre 93

principle. The "honeyed terms" (302) of romance are partic

calculated abuse, as the flattering epithets of Celine an

demonstrate. The tales with which courtships are often cond

ing the deceit accompanying professions of love, serve rea

figure of the tale of romance told to them. Hence read

autobiographical narrative, which originate with Jane's learn

story plausible to Miss Temple and are reinforced by Roch

misleading accounts of his past, spread to encompass Jane E

If such are the trepidations deriving from the belief that lan

quite different fears affect those who hold that words poss

to reveal rather than to distort or simply to conceal the truth.

is the conviction that words can turn actions into lies and men

exactly reversing the supposition of the first type of logopho

actions are the proofs of true or false speaking). Language n

seemingly disproportionate to its size. Thus Mrs. Reed will

syllable" (60) from Jane, and Rochester warns her of the dir

careless word" (245). She, of course, discovers firsthand the

word" (342); nevertheless, the silence imposed upon Jane in

fatal word" (342) places her in double jeopardy. Not only d

threaten the integrity of self, but also the inability to make h

with her force of character, leaves no alternative for expre

passionate utterance that-when it does erupt--carries the s

formulations of conventional society and into the inarticulaten

society is quick to associate with insanity-and to use as furt

enforced silence. But rhetorical oppressors, no less than thei

danger. Not only do they typically have the most to lose from

but they are also susceptible to the incoherent excess hear

Rochester's "frantic strain" (345) with Jane.

Afflicted with language fear of either variety, characters

expression and communication. Logophobic lovers of the firs

to the "natural" language of the body as an alternative to

inarticulate" or that "draw you into a snare deliberately laid

all spoken words are either definitionally or intentionally e

lover relies upon "words almost visible" (182), the language

trustworthy than its audible counterpart. A suitor's promise

can be trusted only if corroborated by the eyes, "the faithful i

soul. Apprehensive lovers may even find themselves in the p

accepting silence as the only reliable expression of erotic des

logic, if a glib tongue signals a shallow heart, then Jane's vo

eloquent statement of love.

Logophobic lovers of the second type, fearing language's

speaking rather than for tergiversation, turn neither to body

they seek refuge in the very forms of social confabulation

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

94 The Journal of Narrative Technique

experiencing the first kind of language fear. Or, when this diversionary tack fai

as it must, they invoke a higher "supernatural" discourse. In the first instance, t

"conventionally vague and polite" (162) language of social interchange is used

conceal awkward or isolating silences. Flirtation in the "key of sweet subdue

vivacity" (197) mutes contrapuntal voices and avoids the double-edged violen

accompanying unbridled expressions of passion. But erotic desire remains un

voiced in these colloquies and ultimately demands a "supernatural" alternative

conventional or mildly unconventional courtship discourse. When Jane can

longer suppress her love, she claims to speak not "through the medium of cust

conventionalities, nor even of mortal flesh" (281); when Rochester seems on t

brink of losing her, he appeals to her "spirit ... not [her] brittle frame" (345).

lovers wishfully attempt to circumvent the soul's unreliable interpreters by m

of an unmediated appeal from and to the soul.

In practice, these alternative languages prove to be as problematic as that to wh

they are a reaction. Neither "natural" nor "supernatural" discourse reliably rev

the speaker's spirit; neither affords the certitude of a transcendental signifi

Speakers, therefore, find themselves driven back upon the very communicat

forms from which they sought to escape. Rochester, fearing that the "natur

language of his face will belie his asseverations of good character, has no choice b

to ask Jane to "take my word for it" (167). In the same way, his "supernatural" ap

to her spirit gives way to an attempted carnal embrace (345-46), therein mer

reenacting previous courtship patterns. Language and counter-language prov

liable to the same abuses. Furthermore, Brontd's resorting to a logos ex machin

bring her lovers together at the end of the novel is unlikely to restore reade

confidence in linguistic efficacy. There appears to be no escape from the Babe

competing but equally flawed, equally feared, discursive modes.

Logically, the two forms of logophobia would seem to be mutually exclusi

The beliefs that language does not work and works only too well, that love is b

expressed by silence and by oratorical ferocity, are obviously incompati

Dialogically, however, such is not the case. Logophobic lovers are lost in a lingui

labyrinth rife with competing, contradictory, and ultimately unreliable signs.

communicative mode in Jane Eyre, irrespective of individual fears or belief

escapes the possibility of equivocal and potentially destructive use. No langu

stands outside the confines of the labyrinth orof the narrative itself. This unreliabili

therefore, expands to encompass the narrator and even the author, giving read

themselves ample reason for logophobia.2

The logic of the first type of language fear leaves speakers in an irresolvab

dilemma. As Jane's nightmare suggests, if deep feeling is antithetical to articulat

then by necessity and not simply by choice is the subject of talk limited to t

comparatively superficial experiences amenable to linguistic formulation an

convention. It is not simply that words are insufficiently vivid or precise to

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre 95

trusted-not merely a matter of finding the right locution to

issue rather is the efficacy of linguistic expression itself, espe

feelings seem to render the individual incapable of speech. J

suffers from this situational aphasia:

It is one of my faults, that though my tongue is sometimes prom

answer, there are times when it sadly fails me in framing an

always the lapse occurs at some crisis, when a facile word or plaus

is specially wanted to get me out of painful embarrassment. (2

Facile words and plausible pretexts are the currency of social

be conversant in this language, admitting, for instance, that

Reed (262). Nevertheless, she cannot frame heartfelt emotion

does social excuses. Hence her dialogues with Rochester are pe

when she either loses her voice or cannot trust herself to spe

327,425). This inarticulateness is more expressive than langua

"sad" failure in words bespeaks a praiseworthy capacity to f

occasions would signify only the superficiality of the spoken

love, she could not be in love. Jane Eyre thus poses the romanti

is a particularly credible erotic statement. Speechlessness m

say," but its ostensive dimension-the here and now, the vis

unable to speak--says it all.

The expressive dimension of silence--as well as the pervas

gives credibility to it-is emphasized by Bront' s portrayal of

courtship of the upperclasses, for whom silences are invariab

treat the evasions and half-truths of social expedience as int

language of love. For Rochester and his friends, romantic co

primarily by performances, which may be either literal or fi

song of Donna Bianca and Signor Eduardo illustrates the for

rhetorical contests, the latter. In both cases, their actions are im

reiterative. While she "repeat[s] sounding phrases from book

a style of courtship which ... was ... in its very carelessness

In such dramatic performances style counts more than substa

for very little. Success depends less on what individuals say

impersonate, and, of course, the voice heard most frequently

at Thomfield is Byron's.3

Acting of this kind is but a specific instance of the genera

erotic norm among this class, which is "(what is vernacular

(202). To trail is to elicit unwarranted belief or, especially in th

In the vernacular sense as well as in common practice, tr

misleading, a gullible lover either into or out of marriage. Fo

hopes to trick Jane into wedlock, just as Celine trailed him out o

its literal sense also means the opposite, that is, to follow or tr

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

96 The Journal of Narrative Technique

to lead, and Brontd fully exploits this ambiguity. Blanche, for instance, thinks t

she is trailing Rochester in the first sense. In actuality he is trailing her in b

senses-in the first, by concealing his own lack of interest in marrying her and

legal proscriptions against his doing so, and, in the second, by exposing

mercantilist motivation for marriage.

The prototype of these seductive performances in Jane Eyre is an occasion o

apparently different nature: Adele's introduction to her governess. Since ad

courtships, however, are merely a specialized and extended form of introduc

this scene presents, along with Rochester's ward, the defining characteristics

romantic discourse. Equally prominent in Adele's recitation to Jane and in lov

conversations with each other is performance. To introduce herself to the

governess, Adele selects a song and a poem from an apparently extensive, sligh

risque repertoire. The former concerns "a forsaken lady" (184) and the disguis

which she plans to gain revenge on her lover. The latter, a fable by La Fontai

illustrates Adele's "attention to punctuation and emphasis, .... flexibility of v

and ... appropriateness of gesture" (134). These aspects of style, exactly thos

deictic and ostensive references lost in novelistic transcription, are more import

to the meaning of the performance than the words Adele mouths. For not only is

what counts in this society, but on this occasion style identifies the speaker as

mother more than the daughter. In effect, this scene introduces Celine, spea

ventriloquially through her daughter. Jane meets, then, not only a little girl-

"miniature of Celine Varens" (170)-but also her mother-the ghostly wom

whose presence explains Rochester's distaste for his ward's "prattle" (161); t

"wronged" woman whose voice blends with Bertha's laugh in aFuries' chorus f

which he unsuccessfully tries to flee; and the fallen woman whom Jane very nea

becomes, despite conscious intentions to the contrary (298).

Unlike Maisie Farange, whose situation resembles Adele's in several impor

ways, Adele can only quote; she cannot speak.4 In impersonating Celine, her o

voice is largely eclipsed. Yet her unselfconscious style, "the lisp of childhoo

(134), is both audible and essential to understanding the performance. In the cont

between the vocative strains of mother and daughter, Jane detects both past

present performances, and she intuits a good deal about Celine: "The su

seemed strangely chosen for an infant singer; but I suppose the point of th

exhibition lay in hearing the notes of love and jealousy warbled with the lisp

childhood" (134). Because the song and recitation are double-voiced, Jane is

to infer the mother's "bad taste" (134) in trailing her daughter for her frien

amusement.

Jane's acuity and sensitivity to the double-voiced quality of performance do not

characterize her reading, however, when her own heart is at stake. When she

observes the love talk of Blanche and Rochester, she is inclined to listen monophonically. For example, during the game of charades, Blanche and Rochester mime

both a wedding ceremony and the ventriloquial courtship of Rebecca by Isaac

through Eliezer. The subject, Bridewell, is replete with ironic echoes concerning

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre 97

marrying well, the imprisoning effects of not doing so, and th

consequences of ignoring conjugal law. ("Bridewell" is also an e

wordplay when it is agreed that Rochester resembles Bothwel

husband of Mary Queen of Scots. "Both-well" extends the mea

to the situation of the would-be bigamist.) Even more telling

ironies, however, is the structural function of the scene, espe

the issues of language and performance.

The game of charades is both an embedded figure and a spec

typical practice of conversation and courtship. In the game,

as playthings; in lovers' talk generally, they are treated as

disguised as something quite serious. Under the aegis of

attitudes toward the language of love are given free reign. Th

of the game allow words to be severed from one context and ap

to another. The severance is of a distinctive nature: con

significance (yielding in this instance the words "bride" and

literal and arbitrary text ("Bridewell"). Although guessing th

of play, the term has no semantic connection with either the pr

combination of words that constitute it. The visual and referen

"bride" and "well" correct choices has nothing to do with the

reasoning producing the correct answer, "Bridewell." Su

language that sounds right, irrespective of reference. Signi

signifiers refer only to other signifiers.

This situation obtains outside the game whenever courtsh

impersonation and quotation rather than by statement. Word

words; texts and contexts are severed and arbitrarily juxtapose

case in Rochester's gipsy disguise and less obviously so in his

The aristocrats' charades further recall Adele's performance

dramatic impersonation and both feature "notes of love and

child's performance is innocent, her guardian's transformatio

figurative game of charades (in part by using the literal game

ventriloquism of the dramatic performance is compounded

conscious manipulation of texts and dramatis personae. I

tableaux, Eliezer (played by Rochester) speaks ventriloquially f

Rebecca (played by Blanche). Presumedly, Eliezer is also Roc

Blanche. At least, no one in the room seems hesitant to apply th

(the text) to the lives of the players (the context). This applicat

the structural procedure of charades but reverses its semio

audience restores the missing signifieds by going outside th

game. Rochester plays upon this manoeuver in joking w

whatever I am, remember you are my wife; we were married

presence of all these witnesses" (214). The joke is on Blan

become the bride in life that she was in the pantomime. Th

"witnesses," who similarly clothe themselves in illusion.

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

98 The Journal of Narrative Technique

freedom of play, they conflate text and context with impunity. None interpre

scene correctly because all rely on the shared, though unannounced, rules

amorous pursuit and discourse that Rochester exploits.

Even Jane, who knows little about such rules or charades (211), misconstru

many-voiced performance. Although "Jealousy" rather than "Bridewell" mig

the more accurate guess of the charade's meaning, its significance is not conc

and cannot be encapsulated in language. Rochester's objective is perlocutiona

wants Jane to feel jealousy, therefore, to be amenable to his illicit plans. In ter

the dynamics of introduction and seduction, he is both Celine and Adele, that is

jaded director indulging his poor taste and earnest actor confidently courti

audience's favor. That the two voices go undetected is testimony to his ventrilo

skill (although the ultimate ventriloquist is perhaps St. John Rivers, who in co

claims to speak not only for Jane's mute heart [427] but also for God [431]).

instance, however, Rochester misjudges his audience. The joke is ultimatel

him, for as the first tableau tacitly suggests and he himself wittily jokes, he is

married when he woos. When Jane ultimately discovers the two voices th

bigamist of necessity possesses, she very nearly acquiesces to her own traili

An additional aspect of charades returns us to the question of visual langu

an alternative to the pervasive use and distorting echoes of love talk. Cha

emphasize the pictorial over the verbal. Although words are the object of the g

its procedures are pantomimic. Its interest and challenge lie in the skills of

presentation and interpretation. Charades, therefore, are the appropriate ch

a logophobic society whose very commitment to rhetorical performances oc

a mistrust of them. Outside the game, the fear of language and the concom

appeal to the visual are manifest in an endemic tendency to read faces rathe

to trust words. Eyes, Jane tells us, are faithful interpreters of the soul (

Language too often provides either a veneer of social ease hiding poten

disruptive feelings or a facade of romantic grace concealing devious inten

Countenances, on the contrary, provide direct and reliable expressions of fe

The language of looks, for example, helps Jane to interpret her employ

troubled relationship with Mason. While Rochester utters only words of succ

face expresses what his "plausible pretexts" attempt to conceal. But Jane

insufficient attention to the drastic difference between Rochester's bi-lin

messages. She tends to trust looks rather than words; therefore, she monologiz

scene, suppressing its incongruous notes. When she struggles to understan

feelings for Rochester, she concludes that she must love him, becaus

"understand[s] the language of his countenance and movements" (204). She re

to this language when he proposes. Fearing that he "play[s] at farce" (283)

consults his visage, and only after reading his look in the moonlight does she a

the offer of his hand.

Rochester, too, places great value on the unspoken language of faces. In fa

he retells it, a "speechless colloquy" (296) directly leads to his engagement.

confident of his ability to read others' visages, and early on he tells Jane: "b

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre 99

by the by, what you express with that organ [the eye]; I am qui

language" (167). Although this claim is tarnished by his subse

her eye color (287), he repeatedly relies upon the language of l

talk is often no more than so much conventional nonsense an

Thus when Jane asks if he is not rather capricious in his trea

replies that he can be trusted with women of "clear eye and el

Rochester perhaps refines his society's standard of truthfulne

those statements made in both languages; nevertheless, his ow

proves that neither expressive mode, even in combination, is

Rochester's equivocal use of the language of looks is obvious

to be a gipsy fortune-teller and to construe Jane's character fro

forehead, about the eyes, and in the eyes themselves, in the lines

27). That his own face is blackened and shaded by a hat provi

of his duplicity. In general he seems to take a perverse p

countenance: "it [is] scarcely more legible than a crumpled, sc

He exploits this illegibility to keep interlocutors in disadvanta

expressions are used in the same way as words are, that is, to co

clarify. "[O]ne of his queer looks" (274) easily frustrates Mr

strange and equivocal demonstrations" (251) are equally conf

reader as Jane.

All performances and languages contain the discordant note

audiences to their unreliability. None fulfills generic expecta

recital to Rochester's fortune-telling, which on this occasion lea

fortune being told by his customer.6 The inherent inconsisten

discourse is signalled by the one line of Adele's recitation that

vous donc? lui dit un de ces rats; parlez! (134).? The peremptor

is appropriate to Rochester's discursive method (164, 290, 45

impatient, even aggressive, tone of many of the novel's "parle

line seems strangely chosen if it is intended to illustrate Adele's

The question, "Qu'avez-vous donc?", self-reflexively asks wha

scene, because it is not a question of the kind that defines int

you?"), and it is not uttered by the expected person (Should

Adele?). And, of course, it is not a question at all, but a quotation

introduces a former mistress on a stage already crowded by th

and a fiancee.

The discordant notes echoing throughout Adele's performan

to envelop the narrator and her readers. The choice of this

repeated by Adele and the consequent notes of incongruity

control and skill. But how are readers to respond when the n

precisely the amusement that Celine apparently found in Adel

is in poor taste? The suspicion of the uses to which language

from characters to narrator and author. For example, our rea

euphemism (related by Jane) that describes her mother's runn

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

100 The Journal of Narrative Technique

a musician as going "to the Holy Virgin" (133, 176) is presumedly no different fr

Celine's enjoyment at "hearing notes of love and jealousy warbled with the lis

childhood." In effect, the scene manifests the kind of dialogical exploitation th

appears to reject. Readers, caught up in a tale of trailing, may begin to suspect

narrator's intentions with regard to them.

The burlesque depictions of Georgiana and Eliza Reed, as well as of the Dowag

and Miss Ingram, are further examples. Readers are apt to enjoy the lampoon of R

Brocklehurst, especially when the sight of curly hair sends him into a fit o

fundamentalist zeal: "Why, in defiance of every precept and principle of this hou

does she conform to the world so openly-here in an evangelical, charit

establishment-as to wear her hair one mass of curls?" (96). That his own daugh

boast "a profusion of light tresses, elaborately curled" (97) heightens the satire

the scene and the contempt for Brocklehurst. But the narrator, who ridicules

hypocrisy, indulges in it when presenting characters for whom she maintain

degree of animus. The very "top-knots" ordered guillotined by Brocklehurst

also taken by Jane to be a sign of worldliness and superficiality and are used by

narrator to convey disapprobation. Georgiana Reed has "hair elaborately ringle

(60, 257) and interweaves "her curls with artificial flowers" (62); Adele flaunt

redundancy of hair falling in curls to her waist" (132, 199); Blanche, whose hai

a "jetty mass of curls" (189) is seldom mentioned without reference to thes

"[c]raven ringlets" (191, 196, 201, 207, 214); and Rosamund Oliver, too, displ

"the ornament of rich, plenteous curls" (389, 391, 393, 395). If with Miss Tem

we laugh at Brocklehurst (appropriately her silent mockery takes the form o

"involuntary smile that curled" her lips [96]), must we then not include the narr

in our critical amusement?'

Even more problematic, however, is the novel's presenting an interpretive n

that is inaccessible to its readers. Adele's introduction implicitly introduces

hermeneutics of performance that can be applied to dramatized discourse in gene

and especially to recitational courtship. To hear only a speaker's voice and to ig

the voice of quotation is necessarily to misconstrue the scene. Audiences and

auditors must be sensitive to at least three factors: utterance (the speaker), text

source), and context (the situation). Readers, however, are denied acces

utterance and may at best guess about the narrator's texts. Writing occludes

ostensive reference essential to interpretation. The novel thus posits a hermene

ideal that can never be applied to novels themselves. While readers may be insulat

to some extent from the trailing by characters, they are all the more susceptible

the "sweet lies" (190) of the narrator.

Unlike conventional autobiographies, Jane Eyre does not begin with an accou

of the protagonist's birth or earliest memory. Rather, the novel opens with

reserved heroine's discovery of "quite a new way of talking" (71). Jane's ini

words, like Adele's recitation of LesLigues des Rats, sound the note that somet

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre 101

is wrong: "What does Bessie say I have done?" (39). When John

for "impudence in answering mamma" (42), Jane likens him t

emperors, a comparison drawn "in silence, which I never thou

declared aloud" (43). But when she does speak out, the "infantin

is imprisoned in the Red Room. Her voice will not be muted, h

verbal rebellions are even more explosive. First, in a "stra

declaration" (59), she renews and expands her attack upon the R

refusing to be banished to the nursery-a place of enforced chil

solitary confinement-she disruptively intrudes upon the adult

routing her aunt from the breakfast-room. In this scene, Mrs. Re

"in a tone which a person might address an opponent of adult age

reduced to murmuring "sotto voce" (68). The force of Jane's tira

aunt continues to suffer from it on her deathbed: "I feel it q

understand: how for nine years you could be patient and quie

treatment, and in the tenth break out all fire and violence" (26

Mrs. Reed identifies a pattern of quietude infrequently but conv

by speech that characterizes Jane throughout her life. Such violen

her interlocutors' logophobia. While she describes herself

Lowood and is called "no talking fool" (181) by Rochester

irrepressible in certain circumstances. First with Mrs. Reed a

Rochester, she cannot refrain from speaking:

it seemed as if my tongue pronounced words without my will con

their utterance: something spoke out of me over which I had no c

Speak I must. (68)

An impulse held me fast-a force turned me round. I said-or som

me said for me, and in spite of me-(273)

I said this almost involuntarily ... The vehemence of emotion, stirre

and love within me, was claiming mastery, and struggling for full

asserting a right to predominate, to overcome, to live, rise, and rei

yes-and to speak. (279-81)

The direct, passionate, and preternaturally coherent speech t

impulses stands as the opposite to the loss of voice that Jane o

ences at times of deep feeling. At these moments, nothing

Rochester calls "the Lowood constraint... controlling your featu

voice" (169). The "infantine Guy Fawkes" speaks out to resist

efforts of her employer, when he suggests packing her off to

benefactor, when Rivers proposes taking her to India. She refus

of marriage; she subverts the protocol of the former's. Rochest

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

102 The Journal of Narrative Technique

much exaggeration, that " by the by, it was you who made me the offer" (291)-a

offer she repeats at Ferndean, "rashly overleap[ing] conventionalities" (460). As i

the scenes of Adele's introduction and Rochester's fortune-telling, the unexpecte

person asks the questions. In this instance-to reverse the earlier formulationmight be said that if Jane does not speak love, she cannot be in love.

This engagement is consistent with Jane's and Rochester's unorthodox court-

ship. The "blunt sentence[s]" (68) that shocked Mrs. Reed are their ordinary form

of intercourse, and their colloquies are a counterpoint of his "impetuous republican

(308) and her "ready and round" (341) answers. Rochester refuses to be constrain

by the norms of polite conversation, exclaiming, "Confound these civilities!" (161

He asks Jane to "dispense with a great many conventional forms and phrases" (16

because they stifle spontaneity and frustrate naturalness (170). Her disregard of

discursive amenities ultimately rivals his: "The sarcasm that had repelled, the

harshness that had startled me once, were only like keen condiments in a choice dish

their presence was pungent, but their absence would be felt as comparatively

insipid" (217). This harshness is more than a matter of style. The medium becom

the message when Jane credits the sincerity of his marriage proposal precisel

because of its "incivility" (283). Non-conventional and even rude language becomes the sign of truthfulness and the means of intimacy.9

This method of courtship may insulate the lovers from the searing expressions o

love for which Jane Eyre is famous, but it also enmeshes them in the rhetoric

jousting that Rochester and Blanche used to disguise their cool dislike. Both t

pretended and the intended courtships yield lively dialogues pitting the interlocu

tors as verbal antagonists. Wooing begins to resemble a military rather than

romantic engagement, one whose objective is maintaining distance rather tha

establishing common ground. Jane, for instance, deliberately employs a "needle

repartee" (301) to frustrate any show of love: "I whetted my tongue" (301). It is

wonder, then, that Rochester complains that "under the pretence ... of stroking an

soothing me into placidity, you stick a sly penknife under my ear!" (162, also se

306). The effect of this courtship of sharp tongues and pointed conversations is

make distance and detachment the indices of love. Their amorous exchanges a

hardly the "kindly conversation" (333) that Rochester claims to have missed wi

Bertha and that we never see with Blanche. They constitute, rather, another instan

of manipulation and antagonism, albeit a highly eroticized one.

Both courtships--the pretended and the intended-are conducted by perfor-

mance. With Blanche the method is imitative, a courtship by quotation. With Ja

the method is inventive; their discourse is characterized by imaginative conceits

which she typically figures as a fairy and he as an Oriental emir. In the most extend

of these metaphors, Rochester spins a tale of life on the moon, with pink clouds fo

clothing and manna for sustenance. Jane tells Adele "not to mind his badinag

(296), but she herself would do well to borrow from her pupil's "fund of genuin

French skepticism" (296). For his wish to leave the "common world" (296) behin

also expresses his desire to ignore common customs and laws. He is, in more way

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre 103

that Adele understands, "un vrai menteur" (296).

Rochester's wish for a transcendent existence recalls the "supe

to which he and Jane intermittently have recourse. Are thes

passionate protestations any more true or effective than the ro

which they so vividly stand out? John Kucich has suggested

"passionate displays are calculated both to conceal rather than

nature of desire, and to assail the strategic reserve of others

addition, direct and passionate speech is voiced at significant ri

leads to social ostracism at the least and to physical and emotio

worst. The speaker need not have the book thrown at her, as Ja

know that "criminal conversation" exacts a social penalty.

effects of unlicensed expression are even more traumatic. "A c

its furious feelings uncontrolled play, as I had given mine-wit

afterwards the pang of remorse and the chill of reaction" (69).

anger to Mrs. Reed, Jane feels "poisoned" and is unable to find

her books or in nature. Her victory is an "aromatic wine it seem

warm and racy; its after-flavour, metallic and corroding" (70)

This metaphor is also used to describe Jane's adult experience, f

she confesses her love to a man she knows is married. Speaking h

carries her into acting on it. But she resists being swayed by R

that running off to his "whitewashed villa on the shores of the M

if not a form of going to the Holy Virgin, at least violates no

become his mistress, he argues, will be to "transgress a mere h

being injured by the breach" (343). She resists only by recallin

was sane, and not mad-as I am now ... I am insane-quite insan

running fire" (344). The figure of speech with which Jane describ

occasion is related to that she applied to her childhood experien

Of the earlier scene she says:

A ridge of lighted heath, alive, glancing, devouring, would have b

emblem of my mind when I accused and menaced Mrs Reed; the

black and blasted after the flames are dead, would have represented

my subsequent condition, when half an hour's silence and ref

shown me the madness of my conduct. (69-70)

Later, when her hopes of marriage are dashed, she thinks:

Jane Eyre, who had been an ardent expectant woman ... was a co

girl again. ... A Christmas frost had come at midsummer; a whit

storm had whirled over June; ice glazed the ripe apples, drifts

blowing roses; on hayfield and cornfield lay a frozen shroud: lane

night blushed full of flowers, to-day were pathless with untrodden

the woods, which twelve hours since waved leafy and fragran

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

104 The Journal of Narrative Technique

between the tropics, now spread, waste, wild, and white as pine-forests in

wintry Norway. (323)

Whether black or white, the landscape of the soul after such passionate explosion

is cold and barren-as cold as England must seem to someone from the West Indie

as barren as "old thorn trees" (131) must appear to a woman accustomed to tropic

groves.

Bertha, of course, is the extreme of the madness of uncontrolled passion and

expression, but Rochester is no less susceptible to bouts of insanity.'0 In genera

Grace Poole's description of Bertha seems more appropriate to her husband, wh

is consistently "rather snappish, but not 'ragious" (321). He also has period

outcries rivalling Jane's and Bertha's in intensity and violence. After the public

revelation of his secret thwarts the plan to take a second wife, he too becomes craze

"His voice was hoarse; his look that of a man who is just about to burst a

insufferable bond and plunge headlong into wild licence" (330). Rochester

"flaming glance" is like the "draught and glow of a furnace" (344) and poses a

greater threat than Bertha's pyromania. Jane, in fact, fears that her disappearan

will drive Rochester insane (454). If the possibly hyperbolic innkeeper is to be

believed, the master of Thornfield does become "savage--quite savage on h

disappointment: he never was a mild man, but he got dangerous, after he lost he

(452). Whether its effects are railing and insanity or merely trailing and duplicit

expressing love in Jane Eyre is a risky proposition.

Logophobia is an endemic phenomenon, spreading from the central character

the narrator and even to the author herself. The nascent vocal power of the

protagonist coincides with the initial appearances of the autobiographer, Jane Eyre

and of the novelist, Currer Bell. The fledgling author's tentative assertions of se

closely resemble those of the youthful protagonist. When BrontS refers to Curr

Bell as "an obscure aspirant" and a "struggling stranger" (35), one must think o

Jane, who is surely both of these things, both as young orphan when the novel open

and as a novice author when it closes. Her autobiography, written after ten years o

married life, confirms the pattern, noted by Mrs. Reed, of her "break[ing] out all fi

and violence" in the tenth year of their acquaintance. A habitually quiet demeano

combined with unexpectedly vehement language, contributes to the Reed household

feeling that Jane is duplicitous. Given the "fire and violence" of the novel itsel

readers may harbor similar suspicions.

Despite their prejudice, the Reeds are fully justified in suspecting, if n

duplicity, then at least dissimulation, from Jane. Abigail Abbott expresses th

general sentiment when she says, "I never saw a girl of her age with so much cover

(44). For instance, as Jane awaits John Reed's blow, she entertains herself by

"mus[ing] on the disgusting and ugly appearance of him who would presently de

it" (42). Her silent mockery of the master, which is never uttered, is, however

plainly heard in the narrator's tone: "Habitually obedient to John, I came up to h

chair: he spent some three minutes in thrusting out his tongue at me as far as he co

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre 105

without damaging the roots" (42). The incipient but silent wit o

child receives expression in the hyperbole and caricature of t

narrator, who settles the girl's debt against her persecutors." T

tongue thrust out to the point of damaging the roots is the product

of a sardonic adult, indeed, the very "whetted tongue" that Jane a

Rochester and more unmercifully to characters like the Reeds.

Further indication that the adult narrator is capable of the "dan

(50) suspected in the child is the occasional inconsistency in t

example, Jane tells the story of the wronged but generously p

returning to her aunt's deathbed: "Forgive me.... If you could be

no more of it, aunt, and to regard me with kindness and forgiven

full andfree forgiveness" (267-68, my emphasis). She claims, som

the fact, that the "gaping wound of my wrongs was now... quit

even twenty years later, Jane can neither overlook nor forgive Mr

So importunate is her resentment that she actually addresses the

story: "Yes, Mrs Reed, to you I owe some fearful pangs of ment

ought to forgive you" (52). Her "ought" clearly indicates that sh

her aunt, whatever impression she wishes to convey by dram

conversations.

In the course of her autobiography, Jane claims to be "merely

(140), and she jokes with this idea when offering a mock apolog

reader ... for telling the plain truth" (141). Such jokes, as Roche

a way of redounding upon the teller. Readers are likely to suspect

from plain, especially since the narrator occasionally treats t

habitually do each other. For instance, the "illustration" (449) of h

seeing the ruins of Thornfield has precisely the effect of Roch

confuses rather than clarifies, encouraging readers to the mista

Rochester is dead. The joke is, of course, on readers, who

implicated in forms of humor shown to be in poor taste. But it is a

who, by reinforcing the logophobia rampant on the level of ac

becomes subject to it.

The novel provides several examples of disingenuous narration

herself "a plain, unvarnished tale" (190) concerning an "indigen

plebeian" (191) in order to destroy romantic illusions about Roc

made aware of the ulterior motives that narration can serve. Jane

in a similar way, as Annette Tromly has shown: "Jane creates

Rochester, Blanche, Rosamund, and herself] to contain and contr

own and others') rather than to represent her subjects" (Troml

taken in by this self-conscious pictorial manipulation, at least

readers should not be surprised to discover narrative used in

adopts the pose of humility and self-effacement when she apologi

autobiography of an "insignificant existence" (115). But this sta

autobiography itself, the writing of which entails no small act of

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

106 The Journal of Narrative Technique

state that the life she tells is "insignificant," but her explanation of the narrative a

editorial method suggests otherwise: "I am only bound to invoke memory wher

know her responses will possess some degree of interest" (115). Writing her ow

story is the conscious and natural culmination of the signature that unconscious

announces her identity to St. John; it is an adult version of the edited tale told to M

Temple to defend herself against the charge of deceit. The narrative, readers ma

suspect, is less autobiography than apologia.

Currer Bell sustains this pose of insignificance, deprecatingly describing he

novel as "a plain tale with few pretensions" (35). Perhaps we are intended to respon

with impatience, as Rochester does when Jane is formally introduced to him: "O

don't fall back on over-modesty" (153). But readers of the "unknown a

unrecommended Author" (35) are likely to be suspicious of the unimposing perso

presented by Currer Bell (the pseudonym itself is a kind of "cover"), especial

when an expression of gratitude to Public, Press, and Publishers, which seeming

augments her facade of docile self-effacement, is immediately followed by an

acerbic attack upon the "timorous or carping few" (35) who find the novel an affro

to religion and morality. Brontd's subsequent response to a critic, which she

describes with sarcastic understatement as "a quiet little chat" (Quarterly 444

evinces the same rhetorical strategy. Her verbal attacks are hardly "framed to tick

delicate ears" (36), and readers are justified in suspecting that what Rochester

described as Jane's "sly penknife" is but another name for the author's sly pen.

Presented with a tale of sensational incident and strong feeling, readers are place

in a position resembling the protagonist's when she watches the arrival of Rocheste

and his guests at Thornfield. Exposed to a fascinating, foreign, but forbidden worl

she experiences

an acute pleasure in looking--a precious yet poignant pleasure; pure gold,

with a steely point of agony: a pleasure like what the thirst-perishing man

might feel who knows the well to which he has crept is poisoned, yet stoops

and drinks divine draughts nevertheless. (203)

Or perhaps like St. John Rivers, we indulge ourselves in a tale of "love rising li

a freshly opened fountain" (399)--though we in all likelihood lack this "cold, ha

man['s]" (400) prophylactic pocket watch. Thoughts of Rosamund Oliver are to hi

like a "sweet inundation" of pastoral fields "assiduously sown with the seed of go

intentions, of self-denying plans. And now it is deluged with a nectarous flood--th

young germs swamped--delicious poison cankering them" (399). His plans surviv

the seductions of art-both Jane's drawing of "the Peri" (389) and her narrative

conjugal contentment. Readers, however, are unlikely to succumb, for the narrat

toys with us as impishly and as mercilessly as Jane does with St. John, enticing

with divine draughts of fiction, sweeping us away upon a flood of nectarous words

The emblem of Jane's and Rochester's passion is the "lightning-struck chestnu

tree" (469). From its "strong roots... unsundered below" (304) a fruitful conjug

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre 107

union emerges-after providential punishment by fire. The emb

ascetic desire is the "overshadowing tree, Philanthropy" (401)

stringy root of human nature" (401) a mighty missionary devel

like a giant the prejudices of creed and caste" (477)-at least afte

and training" (401). Perhaps unnoticed after the gods of orthod

the gardener's task, however, is the poetic "upas tree" (328), t

reader's aesthetic experience. Its "delicious poison" is language

our fears about words and their uses may be as a result of Charl

is precisely because of that art that we have "surfeited [ourselves]

swallowed poison as if it were nectar" (190).

Jane herself experiences the pleasure of devouring books wh

End (376), but this gratification would not seem to explain why sh

one. The personal incentives for self-assertion would seem to ha

when she acquires wealth and relations through inheritance, fol

family through marriage. Furthermore, one would expect Jane, w

slate" (97) had previously exposed her to opprobrium, to avoid t

again. In the first thirty years of her life she pens little more

advertisement and several letters with explicitly practical purp

keep a journal and, unlike Richardson's Pamela (whose situatio

sembles her own), she shows no epistolary aptitude.13 Even a

Lowood, she must admit to having read "[o]nly such books as ca

they have not been numerous, or very learned" (155). How, then

for the emergence of the autobiographer from a character neit

reader?

One possible explanation is that writing serves to maintain a sen

that has typified Jane's relationship to her employer, lover,

Throughout their courtship, she attempts to sequester herself f

avoids him on the evening that he proposes (276), resists setting

(287), dreads its arrival once it has been set (303), and wishes th

on the night before the ceremony is to be performed (307). T

reluctance we might turn to Julia Kristeva's analysis of the erotic

Song of Songs. Although allusions to this book are not among

references to the Old Testament, it offers a number of parallels t

of which can be described in terms of the barriers figured in

dream. For instance, in both texts an economic gap exists between

social status and a privileged man. The rhetorical structures o

oppositional: in both love is expressed by a counterpoint of v

powerful and powerfully erotic poetic dialogue. A third obstacl

juridical. The Song of Songs and Jane Eyre address the anarchic th

and its inclusion within the structures of convention, law, and

Kristeva focuses on the elusive and inaccessible nature of the l

and concludes that "the absolute tension of love for the Othe

centrally important:

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

108 The Journal of Narrative Technique

Supreme authority, be it royal or divine, can be loved as flesh while remaining

essentially inaccessible; the intensity of love comes precisely from that

combination of received jouissance and taboo, from a basic separation that

nevertheless unites. (Kristeva 90)

The "separation that unites" has consistently defined Jane's and Rocheste

situation. Initially, a social proscription divides employer and "paid subordinate

(165). When that gap is overcome by betrothal, she reimposes the econom

obstacle and implements various rhetorical strategies to "keep [him] in reasonab

check" (302). At the very moment that she admits that Rochester has become an id

eclipsing her view of God, she resolves to "maintain that distance between you a

myself most conducive to our real mutual advantage" (301). And just when th

advantage is about to be compromised by marriage, the lovers are separated b

Rochester's pre-existent marriage-a legal hiatus made literal by Jane's parado

cal expression of love, her flight from Thornfield. Marriage threatens the tensi

generating erotic intensity. If the condition that spawned their passion is to

sustained, fulfillment must remain in the future.

An appropriate figure of Jane's and Rochester's love, therefore, is the promis

the linguistic act whose very premise is incompletion and whose force resides in th

tension between desire for and distance from the promised act. When Rochester as

Jane to "[p]romise me one thing," she replies, "I'll promise you anything, sir, th

I think I am likely to perform" (254). In saying this, she alludes to the predicti

rather than the obligational dimension of promising. Emphasis is shifted to t

inherent futurity that is predicted by promises and that sustains their significanc

Promises in Jane Eyre are not so much descriptive of the emotions that give rise t

them as they are constitutive of the anticipatory anxiety upon which those emotio

depend. They speak not of the present, and even less of a fixed point in the future

but of the dynamic indeterminacy defined by these points. There is no bette

example of this than betrothal, which by its very nature enacts a separation-in tim

as well as between intention and action-whose premise is unity. The promise

marry both negotiates and sustains the contradictions between now and then

between the erotic and the social, between jouissance and taboo. As Kristeva put

it

Love in the Song of Songs appears to be simultaneously in the framework of

conjugality and of a fulfillment always set in the future. ... One is thus faced

with a true dialectical synthesis of amorous experience, including its universally disturbing, pathetic, enthusiastic, or melancholy aspect on the one hand,

and its singularly Judaic feature on the other-legislating, unifying, subsum-

ing burning sensuousness toward the One. (Kristeva 98)

Promising is less a synthesis than a dialectical suspension. The marriage promise

places Jane and Rochester in an erotically charged, but essentially ambiguous

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre 109

relation. Their cohabitation is neither concubinal nor conjuga

ence is indulged by deferment and circumscribed by language.

conversing itself becomes an erotic activity. Jane, for instance,

and soothing him by turns" (187). On the other hand, promissor

in the logophobia to which all utterance is subject.

Throughout the novel promising is consistent with the rhe

Promises are typically misleading, not because they will not be

they do not purport to be acts of courting at all. For example,

Rivers elicit or make promises concerning Jane's future employ

the pretense that he will marry Blanche and that Jane must

Rochester asks that she promise to "trust this quest of a situation

responds in similar fashion to her wish for honest employmen

spirit, I promise to aid you, in my own time and way" (375). E

both intend marriage. Thus their promises can only be fulfille

suitors reverse the strategy of Don Juan, who promises to marry

so. In effect, Rochester and Rivers promise not to marry in or

opposite strategies, however, yield an identical result: suspici

guage.'4

By having Jane write the story of her life, Bronta reasserts the distance and

futurity encoded in promises and threatened by marriage. Jane's autobiographical

voice resists the legitimizing and monologizing force of married life, despite her

claim that she and her husband are in "perfect concord" (476). She supports this

conclusion by observing that she and Rochester "talk, I believe, all day long" (476).

Readers who recall that "tete-a-tete conversation" (299) has previously served as

a kind of hand-to-hand combat will not be surprised by this garrulity, but they may

well question Jane's profession of "perfect concord." Given the teasing in- and

misdirections with which she tells Rochester of her life after leaving Thornfield (all

with the aim of eliciting "his old impetuosity" [470]), readers have every reason to

suspect that Jane's voice is once again used to establish the eroticized distance that

typified her betrothal. Furthermore, the Biblical metaphor applied to this marital

unity is double-edged. Jane says that she has become "bone of his bone and flesh

of his flesh" (476, Genesis 2:23). This figure of speech ingeminates the tension

between the sacred and the profane heard previously in Rochester's supernatural

discourse and reinforced by his telling Jane that she, not the "beneficent God" to

whom he appeals for her return, is "the alpha and omega of my heart's wishes"

(471). Her narrative, then, suggests a counterpoint to the happy hum of conjugal

conversation. To write her story is to bring it into question, for she can escape neither

logophobia, which the internal tales of love dramatize, nor the dialectic of distance

and desire, to which all such tales are subject.

As Jane's summary allusion to Genesis suggests, Eve stands behind this wifely

narrative, in addition to the Shulamite maiden and to Delilah." When Rochester

fears Jane's questions, he both pleads and threatens: "for God's sake, don't desire

a useless burden! Don't long for poison--don't turn out a downright Eve on my

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

110 The Journal of Narrative Technique

hands!" (290). His upright wife does prove to be a "downright Eve," however, an

in ways that Rochester cannot envision. The "apple of his eye" (476) offers reader

a seductive narrative fruit that threatens the complacency and univocal power

authority. Brontf's Eve, like the heroine of the Song of Songs, "by her lyrica

dancing, theatrical language, by an adventure that conjugates a submission to

legality and the violence of passion" (Kristeva 99-100), leaves readers with the

ambivalent knowledge that her language is as unreliable as it is nectarous.

State University of New York

Albany, New York

NOTES

1. All parenthetical references, unless otherwise specified, are to Jane Eyre.

2. There have been a number of excellent readings of Jane Eyre in recent years. I wo

like to acknowledge the three by Bodenheimer, Hennelly, and Kucich, as having

particularly helpful to me. I would also like to recognize the students ofmy Britishno

classes who have provided stimulating discussions of Jane Eyre. I mention in parti

an insightful essay on style and the language of courtship written by Sandra Deel

3. The Corsair song itself suggests Byron's presence in Jane Eyre. Byron's influen

Brontd has been widely discussed. See Bloom, Schorer, Stone, and Beaty.

4. Jane alludes to the limits of childhood perception and expression in terms suggestiv

James's "Preface" to What Maisie Knew: "Children can cannot analyse their feelin

and if the analysis is partially effected in thought, they know nothow to express the r

of the process in words" (56, also see 66).

5. In addition to reading Rochester's face, Jane interprets Blanche's (197-98), Mas

(219), Mrs. Reed's (259), and St. John Rivers' (371). Other characters who rely on

language are Helen Burns (101), Mrs. Ingram (206), Mrs. Fairfax (293), and St. J

Rivers (366, 380, 382). (Bronta's interest in phrenology has been well-documented

her biographers. See Chase. For alistof phrenological allusions in the novel, see Dor

Roberts.)

6. Rochester, who has previously (and deviously) suggested through the charades that

marriage is a prison, now hears that story read to him. Jane tells the gipsy that the stories

of wealthy lovers "run on the same theme--marriage; and promise to end in the same

catastrophe-marriage" (228-29).

Other performances are characterized by similar incongruities. The charades, for

instance, contain a revealing anachrony in which a wedding (Tableau I) precedes a

courtship (Tableau II), as of course it does in real life for Rochester.

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre 111

7. The question is asked by a rat of a mouse that seeks the protection

against a voracious cat. In addition to the rhetorical incongruities of

choice of this fable is itself unsettling since the rats, who in self-inte

arrive too late to prevent the cat from eating a mouse.

8. There are few references to the hairstyles of more sympathetic

Temple or Diana and Mary Rivers. Those that do occur typically re

of coiffure (79). The exception are allusions to Diana's "thick cur

9. RobertBemard Martin also makes this point: "Brusqueness, teasin

throughout the novel have always been the mark of sincerity" ( Mart

not, however, question the adequacy of such discursive modes.

10. While Jane can be "a mad cat" (44) and has, by her own admission

insanity (44, 344), Bertha seems chronically to be a "wild animal" (

"lucid intervals of days--sometimes weeks" (336). "[O]ral od

shrieks (235), gibberish (242), yells (322), curses (334), foul v

constitute her primary language. Of the many readings of Bertha's

significance in the novel, John Maynard's is particularly relevant i

is also a monster of excess--far surpassing her prototype Zenobia.

was conceived from Brontd's own awareness of the interconnectio

excess and the suppressive forces it can call up. .... She seems c

Victorian idea of woman falling, when she falls, into comple

punishment follows the Victorian association between sexual exces

her mad curses are about the hidden life of the body: 'such lang

harlot ever had a fouler vocabulary than she ' " (Maynard 106-7)

11. Although these hyperbolic "three minutes" have been read as

youthful perception and articulation, it seems more likely that this

sions are the sarcastic accounts of a mature voice. Temporal exagg

exclusive province of children and are found in the narrative when

example, in her account of the dilatory postmistress at Lowton

typically appear either in broad caricatures of figures like John R

whose public denouncement of Jane as a liar is punctuated with a d

full ten minutes (98)-and Blanche Ingram.

In addition, Brontd usually signals the natural exaggeration of

to the deliberate irony of an adult. For instance, she contradicts J

journey to Lowood is of a "preternatural length," requiring "trave

miles of road" (74), by informing us that the school is fifty miles

Indeed, the child-like perception of her journey is accentuated

summary of her next trip (from Lowood to Thornfield), which is tak

when she is considerably more mature (125). Of her next journey,

Gateshead, nothing at all is said (255).

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

112 The Journal of Narrative Technique

12. Tromly also argues that Jane's narrative is not to be fully trusted, but she excludes Bron

herself from this criticism: 'Throughout the novel Jane's active artistic imagination

shapes the image she presents of herself; clearly Brontd does not intend the reader t

accept the limitations of romantic self-portraiture uncritically" (43).

The extent to which the narrator misleads readers is discussed by Hennelly. H

concludes that as a narrator Jane is neither " 'relatively reliable' like Moll Flanders no

'relatively unreliable' like Molly Bloom. She is somewhere in between the two, bu

more like Molly than has been acknowledged" (Hennelly 704).

Earl A. Knies holds the opposing view: "This complete honesty, this perfect candor

then, provides a structure upon which the reliability of thenarrative is built"(Knies 112)

13. Janet Spens and Jerome Beaty have traced the similarities between Richardson's and

Bronta's novels.

14. Rochester's request that Jane promise to sit up with him on his wedding night (248)

similarly false. When he keeps her to this promise (307), circumstances have change

considerably, for it is Jane not Blanche who is the prospective bride.

Rochester also speaks falsely when Jane asks him to promise "that I and Adele shall

be both safe out of the house before your bride enters it" (254). His bride, of cours

already lives there, so his agreement is doubly misleading because of the incorrec

supposition that it sustains.

15. Delilah figures as the archetypal temptress in both Jane's and Rochester's imagination

(289, 330, 456). See Sullivan, 192-98.

WORKS CITED

Beaty, Jerome. "Jane Eyre and Genre." Genre 10 (1977): 619-54.

."Jane Eyre at Gateshead: Mixed Signals in the Text and Context." VictorianLit

and Society: Essays Presented to Richard Altick. Ed. James R. Kincaid and Alb

Kuhn. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1984. 168-96.

Bloom, Harold. "Introduction." Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre. Ed. Harold Blo

York: Chelsea House, 1987.

Bodenheimer, Rosemarie. "Jane Eyre in Search of Her Story." Papers on Lang

Literature 16 (1980): 387402.

Bront#, Charlotte. "A Word to The Quarterly." Jane Eyre. Ed. Richard J. Dunn. N

W. W. Norton, 1971.

. Jane Eyre. Ed. Q. D. Leavis. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966.

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Logophobia in Jane Eyre 113

Chase, Karen. Eros & Psyche: The Representation of Personality in

Charles Dickens, and George Eliot. New York and London: Meth

Hennelly, Mark M., Jr. "Jane Eyre's Reading Lesson." ELH 51 (1984

James, Henry. "Preface." What Maisie Knew. New York: Charles Scr

Knies, Earl A. The Art of Charlotte Bronte'. Athens: Ohio University P

Kristeva, Julia. Tales of Love. Trans. Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Co

Press, 1987.

Kucich, John. "Passionate Reserve and Reserved Passion in the Works of Charlotte Bront#."

ELH 52 (1985): 913-37.

Martin, Robert Bernard. The Accents of Persuasion: Charlotte BrontFY's Novels. London:

Faber & Faber, 1966.

Maynard, John. Charlotte BrontdY and Sexuality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1984.

Roberts, Doreen. "Jane Eyre and 'The Warped System of Things.' " Reading the Victorian

Novel: Detail into Form. Ed. Ian Gregor. London: Vision, 1980. 131-49.

Schorer, Mark. "Jane Eyre." The World We Imagine: Selected Essays by MarkSchorer. New

York: Farrar, Strauss, & Giroux, 1968. 80-96.

Spens, Janet. "Charlotte Brontd." Essays and Studies by Members of the English Association

14 (1929): 53-70.

Stone, Donald D. The Romantic Impulse in Victorian Fiction. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980.

Sullivan, Paula. "Rochester Reconsidered: Jane Eyre in the Light of the Samson Story."

Bronte Society Transactions 16 (1973): 192-98.

Tromly, Annette. The Cover of the Mask: The Autobiographers in Charlotte Brontf's

Fiction. ELS Monograph Series 26. Victoria, B.C.: University of Victoria Press, 1982.

This content downloaded from 41.227.137.115 on Fri, 16 Sep 2016 09:11:00 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Business Book SummariesDokument197 SeitenBusiness Book SummariesSyed Abdul Nasir100% (6)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Connell Guide To Charlotte BronteDokument144 SeitenThe Connell Guide To Charlotte BronteWiem Belkhiria100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Performing ArtsDokument25 SeitenThe Performing ArtsAngelique Laplana Bañares100% (1)

- Between English and Arabic A Practical Course in Translation - Facebook Com LibraryofHILDokument137 SeitenBetween English and Arabic A Practical Course in Translation - Facebook Com LibraryofHILWiem Belkhiria75% (4)

- Qualitative Research ForDokument46 SeitenQualitative Research ForThanavathi100% (1)

- Recording Reality, Desiring The Real (Visible Evidence)Dokument232 SeitenRecording Reality, Desiring The Real (Visible Evidence)dominicmolise100% (1)

- Peter Lang Film Studies 2013Dokument92 SeitenPeter Lang Film Studies 2013prisconetrunner67% (3)

- Critical Discourse of The FantasticDokument20 SeitenCritical Discourse of The FantasticWiem Belkhiria100% (1)

- Martin M. Winkler - Classical Myth and Culture in The Cinema (2001) PDFDokument361 SeitenMartin M. Winkler - Classical Myth and Culture in The Cinema (2001) PDFDimitrisTzikas100% (3)

- Myths of The Other in The Balkans Eds by PDFDokument333 SeitenMyths of The Other in The Balkans Eds by PDFYiannis Alatzias100% (1)

- Mythology and FolkloreDokument3 SeitenMythology and FolkloreJE QUEST100% (1)

- Feminism and Fairy TalesDokument19 SeitenFeminism and Fairy TalesWiem Belkhiria80% (5)

- Lieberman (1986) Some Day My Prince Will ComeDokument17 SeitenLieberman (1986) Some Day My Prince Will ComeWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modul Bahasa Inggris Sma N SolokDokument108 SeitenModul Bahasa Inggris Sma N SolokmonickmahndaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Child of Nature, The Child of Grace, The Unresolved Conflict in Jane EyreDokument20 SeitenThe Child of Nature, The Child of Grace, The Unresolved Conflict in Jane EyreWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Relationship Between Psychology and LiteratureDokument4 SeitenThe Relationship Between Psychology and LiteratureWiem Belkhiria0% (2)

- Freud UncannyDokument22 SeitenFreud UncannyChris J RudgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Defense of Ugly WomenDokument140 SeitenIn Defense of Ugly WomenWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Always Sympathize! Surface Reading, Affect, and George Eliot's RomolaDokument19 SeitenAlways Sympathize! Surface Reading, Affect, and George Eliot's RomolaWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Towards A History of Intertextuality in Literary and Culture StudDokument10 SeitenTowards A History of Intertextuality in Literary and Culture StudWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Magic Realism in Song of SolomonDokument6 SeitenMagic Realism in Song of SolomonWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 51013109Dokument18 Seiten51013109Rehab ShabanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The South in Song of SolomonDokument16 SeitenThe South in Song of SolomonWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Genre and Intertextuality Analysis of THDokument9 SeitenGenre and Intertextuality Analysis of THWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Excess and Restraint in JeDokument14 SeitenExcess and Restraint in JeАна МладеновићNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Can T You Love Me The Way I Am FairDokument28 SeitenWhy Can T You Love Me The Way I Am FairWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reader I Buried Him PDFDokument20 SeitenReader I Buried Him PDFWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Patriarch of One's OwnDokument19 SeitenA Patriarch of One's OwnWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Burning Daylight Volume 2Dokument78 SeitenBurning Daylight Volume 2Wiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sympathy in Jane EyreDokument26 SeitenSympathy in Jane EyreWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intertextuality: Interpretive Practice and Textual StrategyDokument10 SeitenIntertextuality: Interpretive Practice and Textual StrategyWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Husbands and Gods As Shadowbrutes - Beauty and The Beast From ApulDokument14 SeitenHusbands and Gods As Shadowbrutes - Beauty and The Beast From ApulWiem BelkhiriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Narrative Writing CharacteristicsDokument2 SeitenNarrative Writing Characteristicsapi-293845244Noch keine Bewertungen

- Principles. Elements. Techniques and Devices of Creative NonfictionDokument11 SeitenPrinciples. Elements. Techniques and Devices of Creative NonfictionDonabel ValdezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1Dokument70 Seiten1Randy Palao-Fuentes HubahibNoch keine Bewertungen

- QuezonDokument36 SeitenQuezonvonneNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Wunderkammer-Gesamtkunstwerk Model A PDFDokument8 SeitenThe Wunderkammer-Gesamtkunstwerk Model A PDFjlnederNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLP #9 Eng 7Dokument2 SeitenDLP #9 Eng 7Lenn DonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabus q1 g7 Sy 16-17Dokument5 SeitenSyllabus q1 g7 Sy 16-17Keith Ann KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- 24 1.0166423 FulltextDokument38 Seiten24 1.0166423 Fulltextmary chris serranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophical Bases of ResearchDokument49 SeitenPhilosophical Bases of Researchapi-222431624Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cmap Sample EnglishDokument13 SeitenCmap Sample EnglishDante Jr. BitoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harvard OCS - Personal Statement and SecondariesDokument5 SeitenHarvard OCS - Personal Statement and SecondariestheintrepiddodgerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bed Bug and The LouseDokument10 SeitenBed Bug and The LouseMa. Concepcion DesepedaNoch keine Bewertungen