Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Hur Tin Yang Vs People

Hochgeladen von

diamajolu gaygonsOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Hur Tin Yang Vs People

Hochgeladen von

diamajolu gaygonsCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 195117

HUR TIN YANG,

Petitioner,

Present:

- versus -

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES,

Respondent.

VELASCO, JR., J., Chairperson,

PERALTA,

ABAD,

MENDOZA, and

LEONEN, J.J.

Promulgated:

AUG l 4 2013 rt/(&0~

I

X-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------X

RESOLUTION

VELASCO, JR., J.:

This is a motion for reconsideration of our February I, 2012 Minute

2

Resolution 1 sustaining the July 28, 201 0 Oecision and December 20, 201 0

Resolution-' of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. CR No. 30426,

finding petitioner Hur Tin Yang guilty beyond reasonable doubt of the crime

of Estaj'a under Article 315, paragraph I (b) of the Revised Penal Code

(RPC) in relation to Presidential Decree No. 115 (PO 115) or the Trust

Receipts Law.

In twenty-four (24) consolidated Informations, all dated March 15,

2002, petitioner Hur Tin Yang was charged at the instance of the same

complainant with the crime of Estafa under Article 315, par. 1(b) of the

RPC, ~ in relation to PO 115, 5 docketed as Criminal Case Nos. 04-223911 to

1

Rollo. p. 252.

c Id. at 57-87. Penned by Associa;c Justice Isaias Dicdican and concurred in by Associate Justice~

Stephen C. Cruz and Danton Q. Bucser.

' ld. at 88-89 .

.J Ar1. 315. SHindling (estaji1!.

Al1\ person \\ho shall defraud another b: am of the mean\

mentioned hereinbelow shall be punished by:

:\:\XX

I.

With unfaithfulness or abuse of confidence. namely:

X X X \

(b) B) misappropriating or convening. to the prejudice of another. money. goods or an: other

personal property received by the offender in trust. or on commission. or for administration. or under an;

other obligation involving the duty to make delivery oC or to return the same. even though such obligation

Resolution

G.R. No. 195117

34 and raffled to the Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch 20. The 24

Informationsdiffering only as regards the alleged date of commission of

the crime, date of the trust receipts, the number of the letter of credit, the

subject goods and the amountuniformly recite:

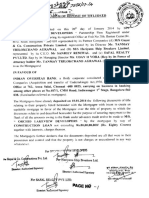

That on or about May 28, 1998, in the City of Manila, Philippines,

the said accused being then the authorized officer of SUPERMAX

PHILIPPINES, INC., with office address at No. 11/F, Global Tower,

Gen Mascardo corner M. Reyes St., Bangkal, Makati City, did then and

there

willfully,

unlawfully

and

feloniously

defraud

the

METROPOLITAN

BANK

AND

TRUST

COMPANY

(METROBANK), a corporation duly organized and existing under and by

virtue of the laws of the Republic of the Philippines, represented by its

Officer in Charge, WINNIE M. VILLANUEVA, in the following

manner, to wit: the said accused received in trust from the said

Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company reinforcing bars valued at

P1,062,918.84 specified in the undated Trust Receipt Agreement covered

by Letter of Credit No. MG-LOC 216/98 for the purpose of holding said

merchandise/goods in trust, with obligation on the part of the accused to

turn over the proceeds of the sale thereof or if unsold, to return the goods

to the said bank within the specified period agreed upon, but herein

accused once in possession of the said merchandise/goods, far from

complying with his aforesaid obligation, failed and refused and still fails

and refuses to do so despite repeated demands made upon him to that

effect and with intent to defraud and with grave abuse of confidence and

trust, misappropriated, misapplied and converted the said

merchandise/goods or the value thereof to his own personal use and

benefit, to the damage and prejudice of said METROPOLITAN BANK

AND TRUST COMPANY in the aforesaid amount of P1,062,918.84,

Philippine Currency.

Contrary to law.6

Upon arraignment, petitioner pleaded not guilty. Thereafter, trial on

the merits then ensued.

The facts of these consolidated cases are undisputed:

Supermax Philippines, Inc. (Supermax) is a domestic corporation

engaged in the construction business. On various occasions in the month of

April, May, July, August, September, October and November 1998,

be totally or partially guaranteed by a bond; or by denying having received such money, goods, or another

property.

5

Trust Receipts Law, Section 13. Penalty clause. The failure of an entrustee to turn over the

proceeds of the sale of the goods, documents or instruments covered by a trust receipt to the extent of the

amount owing to the entruster or as appears in the trust receipt or to return said goods, documents or

instruments if they were not sold or disposed of in accordance with the terms of the trust receipt shall

constitute the crime of estafa, punishable under the provisions of Article Three hundred and fifteen,

paragraph one (b) of Act Numbered Three thousand eight hundred and fifteen, as amended, otherwise

known as the Revised Penal Code. If the violation or offense is committed by a corporation, partnership,

association or other juridical entities, the penalty provided for in this Decree shall be imposed upon the

directors, officers, employees or other officials or persons therein responsible for the offense, without

prejudice to the civil liabilities arising from the criminal offense.

6

Rollo, pp. 58-59.

Resolution

G.R. No. 195117

Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company (Metrobank), Magdalena Branch,

Manila, extended several commercial letters of credit (LCs) to Supermax.

These commercial LCs were used by Supermax to pay for the delivery of

several construction materials which will be used in their construction

business. Thereafter, Metrobank required petitioner, as representative and

Vice-President for Internal Affairs of Supermax, to sign twenty-four (24)

trust receipts as security for the construction materials and to hold those

materials or the proceeds of the sales in trust for Metrobank to the extent of

the amount stated in the trust receipts.

When the 24 trust receipts fell due and despite the receipt of a demand

letter dated August 15, 2000, Supermax failed to pay or deliver the goods or

proceeds to Metrobank. Instead, Supermax, through petitioner, requested the

restructuring of the loan. When the intended restructuring of the loan did not

materialize, Metrobank sent another demand letter dated October 11, 2001.

As the demands fell on deaf ears, Metrobank, through its representative,

Winnie M. Villanueva, filed the instant criminal complaints against

petitioner.

For his defense, while admitting signing the trust receipts, petitioner

argued that said trust receipts were demanded by Metrobank as additional

security for the loans extended to Supermax for the purchase of construction

equipment and materials. In support of this argument, petitioner presented as

witness, Priscila Alfonso, who testified that the construction materials

covered by the trust receipts were delivered way before petitioner signed the

corresponding trust receipts.7 Further, petitioner argued that Metrobank

knew all along that the construction materials subject of the trust receipts

were not intended for resale but for personal use of Supermax relating to its

construction business.8

The trial court a quo, by Judgment dated October 6, 2006, found

petitioner guilty as charged and sentenced him as follows:

His guilt having been proven and established beyond reasonable

doubt, the Court hereby renders judgment CONVICTING accused HUR

TIN YANG of the crime of estafa under Article 315 paragraph 1 (a) of the

Revised Penal Code and hereby imposes upon him the indeterminate

penalty of 4 years, 2 months and 1 day of prision correccional to 20 years

of reclusion temporal and to pay Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company,

Inc. the amount of Php13,156,256.51 as civil liability and to pay cost.

SO ORDERED.9

TSN, April 24, 2006, p. 13.

Rollo, p. 40.

9

Id. at 206. Penned by Judge Marivic T. Balisi-Umali.

8

Resolution

G.R. No. 195117

Petitioner appealed to the CA. On July 28, 2010, the appellate court

rendered a Decision, upholding the findings of the RTC that the prosecution

has satisfactorily established the guilt of petitioner beyond reasonable doubt,

including the following critical facts, to wit: (1) petitioner signing the trust

receipts agreement; (2) Supermax failing to pay the loan; and (3) Supermax

failing to turn over the proceeds of the sale or the goods to Metrobank upon

demand. Curiously, but significantly, the CA also found that even before the

execution of the trust receipts, Metrobank knew or should have known that

the subject construction materials were never intended for resale or for the

manufacture of items to be sold.10

The CA ruled that since the offense punished under PD 115 is in the

nature of malum prohibitum, a mere failure to deliver the proceeds of the

sale or goods, if not sold, is sufficient to justify a conviction under PD 115.

The fallo of the CA Decision reads:

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing premises, the appeal

filed in this case is hereby DENIED and, consequently, DISMISSED.

The assailed Decision dated October 6, 2006 of the Rregional Trial Court,

Branch 20, in the City of Manila in Criminal Cases Nos. 04223911 to

223934 is hereby AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

Petitioner filed a Motion for Reconsideration, but it was denied in a

Resolution dated December 20, 2010. Not satisfied, petitioner filed a petition

for review under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court. The Office of the Solicitor

General (OSG) filed its Comment dated November 28, 2011, stressing that

the pieces of evidence adduced from the testimony and documents submitted

before the trial court are sufficient to establish the guilt of petitioner.11

On February 1, 2012, this Court dismissed the Petition via a Minute

Resolution on the ground that the CA committed no reversible error in the

10

Id. at 79-80. The CA Decision dated July 28, 2010 reads, The evidence for the accusedappellant further tended to show that the transactions between Metrobank and Supermax could not be

considered trust receipts transactions within the purview of PD No. 115 but rather loan transactions because

the equipment and construction materials, which were the goods subject of the trust receipts, were never

intended to be put up for sale or to be manufactured for ultimate sale as they would be utilized by

Supermax in the prosecution of its various projects and that Metrobank knew beforehand that the proceeds

of the loans would be used to purchase constructions materials because, before the approval of such loans,

documents such as articles of incorporation, by-laws and financial reports of Supermax were submitted to

said bank.

11

Id. at 243-244. The OSG Comment reads, The following pieces of evidence adduced from the

testimony and documents submitted before the trial court are sufficient to establish the guilt of petitioner, to

wit:

First, the trust receipts bearing the genuine signatures of petitioner; second, the two demand letters

of Metrobank addressed to petitioner dated August 15, 2000 and October 11, 20001; and third, the initial

admission by petitioner that he signed as Vice President for Internal Affairs of Supermax.

That petitioner did not sell the goods under trust receipts is of no moment. The offense

punished under Presidential Decree No. 115 is in the nature of malum prohibitum. A mere failure to deliver

the proceeds of the sale or the goods, if not sold, constitutes a criminal offense that causes prejudice not

only to another, but more to the public interest x x x. (Emphasis supplied.)

Resolution

G.R. No. 195117

assailed July 28, 2010 Decision. Hence, petitioner filed the present Motion

for Reconsideration contending that the transactions between the parties do

not constitute trust receipt agreements but rather of simple loans.

On October 3, 2012, the OSG filed its Comment on the Motion for

Reconsideration, praying for the denial of said motion and arguing that

petitioner merely reiterated his arguments in the petition and his Motion for

Reconsideration is nothing more than a mere rehash of the matters already

thoroughly passed upon by the RTC, the CA and this Court.12

The sole issue for the consideration of the Court is whether or not

petitioner is liable for Estafa under Art. 315, par. 1(b) of the RPC in relation

to PD 115, even if it was sufficiently proved that the entruster (Metrobank)

knew beforehand that the goods (construction materials) subject of the trust

receipts were never intended to be sold but only for use in the entrustees

construction business.

The motion for reconsideration has merit.

In determining the nature of a contract, courts are not bound by the

title or name given by the parties. The decisive factor in evaluating such

agreement is the intention of the parties, as shown not necessarily by the

terminology used in the contract but by their conduct, words, actions and

deeds prior to, during and immediately after executing the agreement. As

such, therefore, documentary and parol evidence may be submitted and

admitted to prove such intention.13

In the instant case, the factual findings of the trial and appellate courts

reveal that the dealing between petitioner and Metrobank was not a trust

receipt transaction but one of simple loan. Petitioners admissionthat he

signed the trust receipts on behalf of Supermax, which failed to pay the loan

or turn over the proceeds of the sale or the goods to Metrobank upon

demanddoes not conclusively prove that the transaction was, indeed, a

trust receipts transaction. In contrast to the nomenclature of the transaction,

the parties really intended a contract of loan. This Courtin Ng v. People14

and Land Bank of the Philippines v. Perez,15 cases which are in all four

corners the same as the instant caseruled that the fact that the entruster

bank knew even before the execution of the trust receipt agreements that the

construction materials covered were never intended by the entrustee for

resale or for the manufacture of items to be sold is sufficient to prove that

the transaction was a simple loan and not a trust receipts transaction.

12

Id. at 278.

Aguirre v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 131520, January 28, 2000, 323 SCRA 771, 774.

14

G.R. No. 173905, April 23, 2010, 619 SCRA 291.

15

G.R. No. 166884, June 13, 2012, 672 SCRA 117.

13

Resolution

G.R. No. 195117

The petitioner was charged with Estafa committed in what is called,

under PD 115, a trust receipt transaction, which is defined as:

Section 4. What constitutes a trust receipts transaction.A trust

receipt transaction, within the meaning of this Decree, is any transaction

by and between a person referred to in this Decree as the entruster, and

another person referred to in this Decree as entrustee, whereby the

entruster, who owns or holds absolute title or security interests over

certain specified goods, documents or instruments, releases the same to the

possession of the entrustee upon the latters execution and delivery to the

entruster of a signed document called a trust receipt wherein the

entrustee binds himself to hold the designated goods, documents or

instruments in trust for the entruster and to sell or otherwise dispose of the

goods, documents or instruments with the obligation to turn over to the

entruster the proceeds thereof to the extent of the amount owing to the

entruster or as appears in the trust receipt or the goods, documents or

instruments themselves if they are unsold or not otherwise disposed of, in

accordance with the terms and conditions specified in the trust receipt, or

for other purposes substantially equivalent to any of the following:

1. In the case of goods or documents: (a) to sell the goods or

procure their sale; or (b) to manufacture or process the goods with the

purpose of ultimate sale: Provided, That, in the case of goods delivered

under trust receipt for the purpose of manufacturing or processing before

its ultimate sale, the entruster shall retain its title over the goods whether

in its original or processed form until the entrustee has complied full with

his obligation under the trust receipt; or (c) to load, unload, ship or

transship or otherwise deal with them in a manner preliminary or

necessary to their sale; or

2. In the case of instruments: (a) to sell or procure their sale or

exchange; or (b) to deliver them to a principal; or (c) to effect the

consummation of some transactions involving delivery to a depository or

register; or (d) to effect their presentation, collection or renewal.

Simply stated, a trust receipt transaction is one where the entrustee has

the obligation to deliver to the entruster the price of the sale, or if the

merchandise is not sold, to return the merchandise to the entruster. There

are, therefore, two obligations in a trust receipt transaction: the first refers to

money received under the obligation involving the duty to turn it over

(entregarla) to the owner of the merchandise sold, while the second refers to

the merchandise received under the obligation to return it (devolvera) to

the owner.16 A violation of any of these undertakings

constitutes Estafa defined under Art. 315, par. 1(b) of the RPC, as provided

in Sec. 13 of PD 115, viz:

Section 13. Penalty Clause.The failure of an entrustee to turn

over the proceeds of the sale of the goods, documents or instruments

covered by a trust receipt to the extent of the amount owing to the

16

Ng v. People, supra note 14, at 304.

Resolution

G.R. No. 195117

entruster or as appears in the trust receipt or to return said goods,

documents or instruments if they were not sold or disposed of in

accordance with the terms of the trust receipt shall constitute the crime

of estafa, punishable under the provisions of Article Three hundred fifteen,

paragraph one (b) of Act Numbered Three thousand eight hundred and

fifteen, as amended, otherwise known as the Revised Penal Code. x x x

(Emphasis supplied.)

Nonetheless, when both parties enter into an agreement knowing fully

well that the return of the goods subject of the trust receipt is not possible

even without any fault on the part of the trustee, it is not a trust receipt

transaction penalized under Sec. 13 of PD 115 in relation to Art. 315, par.

1(b) of the RPC, as the only obligation actually agreed upon by the parties

would be the return of the proceeds of the sale transaction. This

transaction becomes a mere loan, where the borrower is obligated to

pay the bank the amount spent for the purchase of the goods.17

In Ng v. People, Anthony Ng, then engaged in the business of

building and fabricating telecommunication towers, applied for a credit

line of PhP 3,000,000 with Asiatrust Development Bank, Inc. Prior to the

approval of the loan, Anthony Ng informed Asiatrust that the proceeds

would be used for purchasing construction materials necessary for the

completion of several steel towers he was commissioned to build by

several telecommunication companies. Asiatrust approved the loan but

required Anthony Ng to sign a trust receipt agreement. When Anthony Ng

failed to pay the loan, Asiatrust filed a criminal case for Estafa in relation

to PD 115 or the Trust Receipts Law. This Court acquitted Anthony Ng

and ruled that the Trust Receipts Law was created to to aid in financing

importers and retail dealers who do not have sufficient funds or

resources to finance the importation or purchase of merchandise, and

who may not be able to acquire credit except through utilization, as

collateral, of the merchandise imported or purchased. Since Asiatrust

knew that Anthony Ng was neither an importer nor retail dealer, it should

have known that the said agreement could not possibly apply to petitioner,

viz:

The true nature of a trust receipt transaction can be found in the

whereas clause of PD 115 which states that a trust receipt is to be

utilized as a convenient business device to assist importers and merchants

solve their financing problems. Obviously, the State, in enacting the law,

sought to find a way to assist importers and merchants in their financing in

order to encourage commerce in the Philippines.

[A] trust receipt is considered a security transaction intended to aid

in financing importers and retail dealers who do not have sufficient funds

or resources to finance the importation or purchase of merchandise, and

who may not be able to acquire credit except through utilization, as

collateral, of the merchandise imported or purchased. Similarly, American

17

Land Bank of the Philippines v. Perez, supra note 15, at 126-127.

Resolution

G.R. No. 195117

Jurisprudence demonstrates that trust receipt transactions always refer to a

method of financing importations or financing sales. The principle is of

course not limited in its application to financing importations, since the

principle is equally applicable to domestic transactions. Regardless of

whether the transaction is foreign or domestic, it is important to note that

the transactions discussed in relation to trust receipts mainly involved

sales.

Following the precept of the law, such transactions affect situations

wherein the entruster, who owns or holds absolute title or security interests

over specified goods, documents or instruments, releases the subject goods

to the possession of the entrustee. The release of such goods to the

entrustee is conditioned upon his execution and delivery to the entruster of

a trust receipt wherein the former binds himself to hold the specific goods,

documents or instruments in trust for the entruster and to sell or otherwise

dispose of the goods, documents or instruments with the obligation to turn

over to the entruster the proceeds to the extent of the amount owing to the

entruster or the goods, documents or instruments themselves if they are

unsold. x x x [T]he entruster is entitled only to the proceeds derived

from the sale of goods released under a trust receipt to the entrustee.

Considering that the goods in this case were never intended for

sale but for use in the fabrication of steel communication towers, the

trial court erred in ruling that the agreement is a trust receipt

transaction.

xxxx

To emphasize, the Trust Receipts Law was created to to aid in

financing importers and retail dealers who do not have sufficient

funds or resources to finance the importation or purchase of

merchandise, and who may not be able to acquire credit except

through utilization, as collateral, of the merchandise imported or

purchased. Since Asiatrust knew that petitioner was neither an

importer nor retail dealer, it should have known that the said

agreement could not possibly apply to petitioner.18

Further, in Land Bank of the Philippines v. Perez, the respondents

were officers of Asian Construction and Development Corporation (ACDC),

a corporation engaged in the construction business. On several occasions,

respondents executed in favor of Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP) trust

receipts to secure the purchase of construction materials that they will need

in their construction projects. When the trust receipts matured, ACDC failed

to return to LBP the proceeds of the construction projects or the construction

materials subject of the trust receipts. After several demands went

unheeded, LBP filed a complaint for Estafa or violation of Art. 315, par.

1(b) of the RPC, in relation to PD 115, against the respondent officers of

ACDC. This Court, like in Ng, acquitted all the respondents on the postulate

that the parties really intended a simple contract of loan and not a trust

receipts transaction, viz:

18

Supra note 14, at 305-307.

Resolution

G.R. No. 195117

When both parties enter into an agreement knowing that the

return of the goods subject of the trust receipt is not possible even

without any fault on the part of the trustee, it is not a trust receipt

transaction penalized under Section 13 of P.D. 115; the only obligation

actually agreed upon by the parties would be the return of the proceeds of

the sale transaction. This transaction becomes a mere loan, where the

borrower is obligated to pay the bank the amount spent for the purchase of

the goods.

xxxx

Thus, in concluding that the transaction was a loan and not a

trust receipt, we noted in Colinares that the industry or line of work

that the borrowers were engaged in was construction. We pointed out

that the borrowers were not importers acquiring goods for resale.

Indeed, goods sold in retail are often within the custody or control of the

trustee until they are purchased. In the case of materials used in the

manufacture of finished products, these finished products if not the raw

materials or their components similarly remain in the possession of the

trustee until they are sold. But the goods and the materials that are used

for a construction project are often placed under the control and custody of

the clients employing the contractor, who can only be compelled to return

the materials if they fail to pay the contractor and often only after the

requisite legal proceedings. The contractors difficulty and uncertainty

in claiming these materials (or the buildings and structures which

they become part of), as soon as the bank demands them, disqualify

them from being covered by trust receipt agreements.19

Since the factual milieu of Ng and Land Bank of the Philippines are in

all four corners similar to the instant case, it behooves this Court, following

the principle of stare decisis,20 to rule that the transactions in the instant case

are not trust receipts transactions but contracts of simple loan. The fact that

the entruster bank, Metrobank in this case, knew even before the execution

of the alleged trust receipt agreements that the covered construction

materials were never intended by the entrustee (petitioner) for resale or for

the manufacture of items to be sold would take the transaction between

petitioner and Metrobank outside the ambit of the Trust Receipts Law.

For reasons discussed above, the subject transactions in the instant

case are not trust receipts transactions. Thus, the consolidated complaints for

Estafa in relation to PD 115 have really no leg to stand on.

The Courts ruling in Colinares v. Court of Appeals21 is very apt, thus:

19

Supra note 15, at 126-127, 129.

The doctrine stare decisis et non quieta movere (stand by the decisions and disturb not what is

settled) is firmly entrenched in our jurisprudence. Once this Court has laid down a principle of law as

applicable to a certain state of facts, it would adhere to that principle and apply it to all future cases in

which the facts are substantially the same as in the earlier controversy. Agra v. Commission on Audit, G.R.

No. 167807, December 6, 2011, 661 SCRA 563, 585.

21

G.R. No. 90828, September 5, 2000, 339 SCRA 609, 623-624.

20

Resolution

G.R. No. 195117

10

The practice of banks of making bonowers sign trust receipts to

facilitate collection of loans and place them under the threats of criminal

prosecution should they be unable to pay it may be unjust and inequitable.

if not reprehensible. Such agreements are contracts of adhesion \\hich

bonowers have no option but to sign lest their loan be disapproved. The

resort to this scheme leaves poor and hapless borrowers at the mercy of

banks. and is prone to misinterpretation x x x.

Unfortunately, what happened in Colinares is exactly the situation in

the instant case. This reprehensible bank practice described in Colinares

should be stopped and discouraged. For this Court to give life to the

22

constitutional provision of non-imprisonment for nonpayment of debts, it

is imperative that petitioner be acquitted of the crime of Estafa under Art.

3 15, par. I (b) of the RPC, in relation to PD 115.

WHEREFORE, the Resolution dated February 1. 2012, upholding

theCA's Decision dated July 28, 2010 and Resolution dated December 20,

20 l 0 in C A-G.R. CR No. 30426, is hereby RECONSIDERED. Petitioner

Hur Tin Yang is ACQUITTED ofthe charge of violating Art. 315, par. 1(b)

of the RPC, in relation to the pertinent provision of PD 115 in Criminal Case

Nos. 04-223911 to 34.

SO ORDERED.

I

J. VELASCO, JR.

'c CoNSTIIl

pa;.mcnt of poll tax.'

TIO'-i.

Art. III. Sec. 20 provides. "No person shall be imprisoned for debt or nnn-

Resolution

G.R. 1\io. 195117

11

\VE CONCUR:

~

ROBERTO A. ABAD

Associate Justice

JOSEC

~

VICT~-L.EONEN

MARVIC MARIO

Associate Justice

......."~

ATTESTATION

I attest that the conclusions in the above Resolution had been reached

in consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the Jinion of

the Comi's Division.

PRES BITE

CERTIFICATION

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution and the

Division Chairperson's Attestation, I certify that the conclusions in the

above Resolution had been reached in consultation before the case \\as

assigned to the writer of the opinion of the Court's Division.

~MARIA LOURDES P. A. SERENO

Chief Justice

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Warehouse ReceiptDokument30 SeitenWarehouse ReceiptShane Fernandez JardinicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reply EditedDokument7 SeitenReply EditedSamii JoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court upholds freeze order on accounts linked to fertilizer fund scamDokument24 SeitenSupreme Court upholds freeze order on accounts linked to fertilizer fund scamAnonymous KgPX1oCfrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elizabeth Lee and Pacita Yu Lee DigestDokument2 SeitenElizabeth Lee and Pacita Yu Lee DigestaaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remr FINAL EXAMINATION 2016Dokument6 SeitenRemr FINAL EXAMINATION 2016Pilacan KarylNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court Rules on Minors' Rights in Life Insurance PoliciesDokument8 SeitenSupreme Court Rules on Minors' Rights in Life Insurance PoliciesAmer Lucman IIINoch keine Bewertungen

- Main Reviewer For The AML Home Study ProgramDokument43 SeitenMain Reviewer For The AML Home Study ProgramMike E DmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bail TranscriptDokument13 SeitenBail TranscriptavrilleNoch keine Bewertungen

- AMLA 3 Republic V Bolante GR 186717 PDFDokument21 SeitenAMLA 3 Republic V Bolante GR 186717 PDFMARIA KATHLYN DACUDAONoch keine Bewertungen

- Crisologo vs. PeopleDokument10 SeitenCrisologo vs. PeopleCourt JorsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Batas Pambansa Blg. 22 An Act Penalizing The Making or Drawing and Issuance of A Check Without Sufficient Funds or Credit and For Other PurposesDokument28 SeitenBatas Pambansa Blg. 22 An Act Penalizing The Making or Drawing and Issuance of A Check Without Sufficient Funds or Credit and For Other PurposesPaul Christian Lopez FiedacanNoch keine Bewertungen

- G, Upreme Qeourt: Second DivisionDokument12 SeitenG, Upreme Qeourt: Second Divisionmarvinnino888Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pcib V Ca 255 Scra 299Dokument6 SeitenPcib V Ca 255 Scra 299cmts12Noch keine Bewertungen

- Midterms: Page - 1Dokument3 SeitenMidterms: Page - 1suigeneris28Noch keine Bewertungen

- Henson, Jr. vs. UCPB General InsuranceDokument2 SeitenHenson, Jr. vs. UCPB General InsuranceXavier BataanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meralco Vs BarlisDokument22 SeitenMeralco Vs BarlischarmssatellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawyers League VsDokument3 SeitenLawyers League VsJuralexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Portugal V IACDokument1 SeitePortugal V IACJoshua PielagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hygienic Packaging Corp. v. Nutri-Asia, Inc PDFDokument26 SeitenHygienic Packaging Corp. v. Nutri-Asia, Inc PDFgrurocketNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ansaldo vs. Court of Appeals 177 SCRA 8, August 29, 1989Dokument9 SeitenAnsaldo vs. Court of Appeals 177 SCRA 8, August 29, 1989Roland MarananNoch keine Bewertungen

- PNB Vs CA and Delfin PerezDokument2 SeitenPNB Vs CA and Delfin PerezCes DavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consent DecreeDokument29 SeitenConsent DecreeJermain GibsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amparo Petition by CourageDokument41 SeitenAmparo Petition by CourageInday Espina-VaronaNoch keine Bewertungen

- OCA Vs CuntingDokument2 SeitenOCA Vs CuntingbowbingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crim Cornejo2Dokument76 SeitenCrim Cornejo2Ambisyosa PormanesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alamayri vs. PabaleDokument25 SeitenAlamayri vs. Pabaleanon_614984256Noch keine Bewertungen

- Legitimes V Intestacy TableDokument2 SeitenLegitimes V Intestacy TableJames Francis VillanuevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Code of Commerce and Ra 8792Dokument10 SeitenCode of Commerce and Ra 8792carlo_tabangcuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meralco Ordered to Pay Additional Backwages to Illegally Dismissed EmployeeDokument11 SeitenMeralco Ordered to Pay Additional Backwages to Illegally Dismissed Employeekristel jane caldozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arts of IncDokument31 SeitenArts of IncMaria Cristina MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agpalo 1Dokument93 SeitenAgpalo 1sujeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs EduarteDokument1 SeitePeople Vs EduarteCarl Philip100% (1)

- Leonen: FactsDokument38 SeitenLeonen: FactsLeroj HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Banking LawsDokument72 SeitenBanking LawsMariel MontonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03 GR 206590Dokument14 Seiten03 GR 206590Ronnie Garcia Del Rosario100% (1)

- Guevarra vs Eala: Lawyer Disbarred for Adulterous AffairDokument18 SeitenGuevarra vs Eala: Lawyer Disbarred for Adulterous Affairafro yowNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artex v. Wellington - JasperDokument1 SeiteArtex v. Wellington - JasperJames LouNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Road To Political MaturityDokument26 SeitenThe Road To Political MaturityEdu.October MoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Malpractice and Damages ComplaintDokument8 SeitenMedical Malpractice and Damages ComplaintResci Angelli Rizada-NolascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Banas vs. Asia Pacific Finance Corporation Promissory Note RulingDokument1 SeiteBanas vs. Asia Pacific Finance Corporation Promissory Note RulingpaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Requirements for buy-bust operationsDokument7 SeitenRequirements for buy-bust operationsJairus Rubio100% (1)

- Pre Trial Brief FinalDokument4 SeitenPre Trial Brief FinalJenyud Juntilla EspejoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gsis Laws JurisprudenceDokument95 SeitenGsis Laws Jurisprudencempo_214Noch keine Bewertungen

- Special Penal LawsDokument2 SeitenSpecial Penal LawsEmil BarengNoch keine Bewertungen

- SAMAYLA, Luriza Legal Forms Week4-5Dokument11 SeitenSAMAYLA, Luriza Legal Forms Week4-5Luriza SamaylaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 34.uy Siuliong vs. Director of Commerce and IndustryDokument7 Seiten34.uy Siuliong vs. Director of Commerce and Industryvince005Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bacalso V PadigosDokument11 SeitenBacalso V PadigosJalynLopezNostratisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurisdiction Over The PersonDokument37 SeitenJurisdiction Over The PersonFelip MatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nego Week 15Dokument13 SeitenNego Week 15akosiquetNoch keine Bewertungen

- TORTS NOTES - PHILIPPINE LAW AND PURPOSESDokument1 SeiteTORTS NOTES - PHILIPPINE LAW AND PURPOSESKim Laurente-AlibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Credit Transactions Outline 2018Dokument3 SeitenCredit Transactions Outline 2018Julian DubaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2009 Bar Question1Dokument4 Seiten2009 Bar Question1Joyce Somorostro Ozaraga100% (1)

- 161264306-Court of Appeals Sample-Decision PDFDokument30 Seiten161264306-Court of Appeals Sample-Decision PDFrobertoii_suarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torts and Damages ExplainedDokument22 SeitenTorts and Damages ExplainedRhodaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electronic Evidence Cases (As Listed in TheDokument11 SeitenElectronic Evidence Cases (As Listed in Themina villamorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondent: Third DivisionDokument9 SeitenPetitioner Vs Vs Respondent: Third Divisionaspiringlawyer1234Noch keine Bewertungen

- HUR TIN YANG v. PEOPLEDokument11 SeitenHUR TIN YANG v. PEOPLEChatNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 195117 August 14, 2013 Hur Tin Yang, Petitioner People of The Philippines, RespondentDokument7 SeitenG.R. No. 195117 August 14, 2013 Hur Tin Yang, Petitioner People of The Philippines, RespondentTovy BordadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 216467Dokument8 SeitenG.R. No. 216467Anonymous KgPX1oCfrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metro vs. Court of Appeals 2000Dokument10 SeitenMetro vs. Court of Appeals 2000Ramon DyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Second Division: Ronnie Caluag, G.R. No. 171511Dokument8 SeitenSecond Division: Ronnie Caluag, G.R. No. 171511diamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Table of Contents ATPDokument2 SeitenTable of Contents ATPdiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ra 9346 Prohibition of Death PenaltyDokument1 SeiteRa 9346 Prohibition of Death Penaltydiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oca Vs RuizDokument4 SeitenOca Vs Ruizdiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cir Vs SolidbankDokument3 SeitenCir Vs Solidbankdiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- SC Adm. Circular No. 12-2000Dokument2 SeitenSC Adm. Circular No. 12-2000diamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Matter 2012 Rule On Mandatory Legal Aid ServiceDokument9 SeitenBar Matter 2012 Rule On Mandatory Legal Aid Servicediamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malabed Vs de La PenaDokument1 SeiteMalabed Vs de La Penadiamajolu gaygons0% (1)

- Bar Matter 2012 Rule On Mandatory Legal Aid ServiceDokument9 SeitenBar Matter 2012 Rule On Mandatory Legal Aid Servicediamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1645Dokument4 Seiten1645Anonymous K286lBXothNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gaanan Vs IacDokument2 SeitenGaanan Vs Iacdiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- SC Adm. Circular No. 12-2000Dokument2 SeitenSC Adm. Circular No. 12-2000diamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malabed Vs de La PenaDokument1 SeiteMalabed Vs de La Penadiamajolu gaygons0% (1)

- Abscbn Vs GozonDokument52 SeitenAbscbn Vs Gozondiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asia International Vs CirDokument3 SeitenAsia International Vs Cirdiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medico-Legal Investigation of DeathDokument10 SeitenMedico-Legal Investigation of Deathdiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cir Vs Kudos MetalDokument2 SeitenCir Vs Kudos Metaldiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marquez Vs Elisan CreditDokument17 SeitenMarquez Vs Elisan Creditdiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marquez Vs Elisan CreditDokument17 SeitenMarquez Vs Elisan Creditdiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oca Vs RuizDokument4 SeitenOca Vs Ruizdiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Special Proceedings Case DigestsDokument9 SeitenSpecial Proceedings Case Digestsjetzon2022Noch keine Bewertungen

- Suites Vs BinaroDokument3 SeitenSuites Vs Binarodiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heirs of Purisima Nala vs. CabansagDokument2 SeitenHeirs of Purisima Nala vs. Cabansagdiamajolu gaygons100% (1)

- MEDICO-LEGAL ASPECTS OF PHYSICAL INJURIES - FinDokument270 SeitenMEDICO-LEGAL ASPECTS OF PHYSICAL INJURIES - Findiamajolu gaygons100% (6)

- Republic of The Philippines Supreme Court Baguio CityDokument12 SeitenRepublic of The Philippines Supreme Court Baguio Citydiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medico-Legal Investigation of DeathDokument10 SeitenMedico-Legal Investigation of Deathdiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Okabe Vs SaturninoDokument11 SeitenOkabe Vs Saturninodiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- BBB Vs AAA GR No. 193225Dokument10 SeitenBBB Vs AAA GR No. 193225diamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medico-Legal Investigation of DeathDokument10 SeitenMedico-Legal Investigation of Deathdiamajolu gaygonsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samuel TesfahunegnDokument83 SeitenSamuel TesfahunegnGetachewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fintech in The Banking System of Russia Problems ADokument13 SeitenFintech in The Banking System of Russia Problems Amy VinayNoch keine Bewertungen

- AdaDokument8 SeitenAdaperapericprcasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Npa PNBDokument70 SeitenNpa PNBSahil SethiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ali Reza Iftekhar - A ProfileDokument2 SeitenAli Reza Iftekhar - A ProfileAthena Hasin0% (1)

- CEZA Regulations - 2018Dokument48 SeitenCEZA Regulations - 2018Eunice Sagun100% (1)

- Experience of Internship in EXIM BankDokument7 SeitenExperience of Internship in EXIM BankMd Shahidul IslamNoch keine Bewertungen

- ATM HackDokument2 SeitenATM HackMasta Dre88% (8)

- Summary JobDokument2 SeitenSummary JobHendry Piqué SNoch keine Bewertungen

- C ZDokument72 SeitenC Zvicky241989Noch keine Bewertungen

- BSP PresentationDokument27 SeitenBSP PresentationMika AlimurongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reported SpeechDokument2 SeitenReported SpeechKinga SzászNoch keine Bewertungen

- Description: Tags: RatesbylendersDokument187 SeitenDescription: Tags: Ratesbylendersanon-968180Noch keine Bewertungen

- DtonDokument122 SeitenDtonUtkarsh SinhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IMF Training Catalog 2013Dokument56 SeitenIMF Training Catalog 2013Armand Dagbegnon TossouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bank reconciliation problem computation of cash balanceDokument2 SeitenBank reconciliation problem computation of cash balanceLoid Gumera LenchicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Importance of the Five Cs of Finance for CreditworthinessDokument3 SeitenImportance of the Five Cs of Finance for Creditworthinessccm internNoch keine Bewertungen

- 28,000 ScriptDokument3 Seiten28,000 ScriptClarence RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- ConclusionDokument2 SeitenConclusionezekiel50% (2)

- Pre Closing Trial BalanceDokument1 SeitePre Closing Trial BalanceEli PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Trade Assignment 2Dokument22 SeitenInternational Trade Assignment 2Gayatri PanjwaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discounting, Factoring and Forfeiting Finance Methods ExplainedDokument33 SeitenDiscounting, Factoring and Forfeiting Finance Methods Explainednandini_mba4870Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rights of Surety Against CreditorDokument16 SeitenRights of Surety Against CreditorPrasenjit Tripathi100% (1)

- NGAS Illustrative Accounting EntriesDokument9 SeitenNGAS Illustrative Accounting EntriesDaniel OngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Know Your Customer Quick Reference GuideDokument2 SeitenKnow Your Customer Quick Reference GuideChiranjib ParialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reverse Mortgage For Dummies PDFDokument290 SeitenReverse Mortgage For Dummies PDFDaisuke GatsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marie Curie Presentation Financial ReportingDokument28 SeitenMarie Curie Presentation Financial ReportingArmantoCepongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Analysis of Public and PrivateDokument31 SeitenFinancial Analysis of Public and Privaten.beauty brightNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prudential Regulations For Corporate / Commercial BankingDokument73 SeitenPrudential Regulations For Corporate / Commercial BankingAsma ShoaibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bankers As Buyers 2023-1Dokument66 SeitenBankers As Buyers 2023-1devi_mamoniNoch keine Bewertungen