Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Jean-Philippe Rameau

Hochgeladen von

Diana GhiusCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Jean-Philippe Rameau

Hochgeladen von

Diana GhiusCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

1 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jean-Philippe Rameau (French: [ filip amo]; 25 September 1683

12 September 1764) was one of the most important French composers

and music theorists of the Baroque era.[1] He replaced Jean-Baptiste

Lully as the dominant composer of French opera and is also considered

the leading French composer for the harpsichord of his time, alongside

Franois Couperin.[2]

Little is known about Rameau's early years, and it was not until the

1720s that he won fame as a major theorist of music with his Treatise

on Harmony (1722) and also in the following years as a composer of

masterpieces for the harpsichord, which circulated throughout Europe.

He was almost 50 before he embarked on the operatic career on which

Jean-Philippe Rameau,

his reputation chiefly rests today. His debut, Hippolyte et Aricie

by Jacques Aved, 1728

(1733), caused a great stir and was fiercely attacked by the supporters

of Lully's style of music for its revolutionary use of harmony.

Nevertheless, Rameau's pre-eminence in the field of French opera was soon acknowledged, and he

was later attacked as an "establishment" composer by those who favoured Italian opera during the

controversy known as the Querelle des Bouffons in the 1750s. Rameau's music had gone out of

fashion by the end of the 18th century, and it was not until the 20th that serious efforts were made

to revive it. Today, he enjoys renewed appreciation with performances and recordings of his music

ever more frequent.

Contents

1 Life

1.1

1.2

1.3

2 Music

2.1

2.2

Early years, 16831732

Later years, 17331764

Rameau's personality

General character of Rameau's music

Rameau's musical works

2.2.1 Motets

2.2.2 Cantatas

2.2.3 Instrumental music

2.2.4 Opera

2.2.4.1 Rameau and his librettists

2.3 Reputation and influence

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

2 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

3 Theoretical works

3.1 Treatise on Harmony, 1722

4 List of works

4.1 Instrumental works

4.2 Motets

4.3 Canons

4.4 Songs

4.5 Cantatas

4.6 Operas and stage works

4.6.1 Tragdies en musique

4.6.2 Opra-ballets

4.6.3 Pastorales hroques

4.6.4 Comdies lyriques

4.6.5 Comdie-ballet

4.6.6 Actes de ballet

4.6.7 Lost works

4.6.8 Incidental music for opras comiques

4.7 Writings

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

Life

The details of Rameau's life are generally obscure, especially concerning his first forty years,

before he moved to Paris for good. He was a secretive man, and even his wife knew nothing of his

early life,[3] which explains the scarcity of biographical information available.

Early years, 16831732

Rameau's early years are particularly obscure. He was born on 25 September 1683 in Dijon, and

baptised the same day.[4] His father, Jean, worked as an organist in several churches around Dijon,

and his mother, Claudine Demartincourt, was the daughter of a notary. The couple had eleven

children (five girls and six boys), of whom Jean-Philippe was the seventh.

Rameau was taught music before he could read or write. He was educated at the Jesuit college at

Godrans, but he was not a good pupil and disrupted classes with his singing, later claiming that his

passion for opera had begun at the age of twelve.[5] Initially intended for the law, Rameau decided

he wanted to be a musician, and his father sent him to Italy, where he stayed for a short while in

Milan. On his return, he worked as a violinist in travelling companies and then as an organist in

provincial cathedrals before moving to Paris for the first time.[6] Here, in 1706, he published his

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

3 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

earliest known compositions: the harpsichord works that make

up his first book of Pices de clavecin, which show the

influence of his friend Louis Marchand.[7]

In 1709, he moved back to Dijon to take over his father's job as

organist in the main church. The contract was for six years, but

Rameau left before then and took up similar posts in Lyon and

Clermont. During this period, he composed motets for church

performance as well as secular cantatas.

In 1722, he returned to Paris for good, and here he published his

most important work of music theory, Trait de l'harmonie

(Treatise on Harmony). This soon won him a great reputation,

and it was followed in 1726 by his Nouveau systme de musique

thorique.[8] In 1724 and 1729 (or 1730), he also published two

more collections of harpsichord pieces.[9]

The Cathedral of Saint-Bnigne,

Dijon

Rameau took his first tentative steps into composing stage

music when the writer Alexis Piron asked him to provide songs for his popular comic plays written

for the Paris Fairs. Four collaborations followed, beginning with L'endriague in 1723; none of the

music has survived.[10]

On 25 February 1726 Rameau married the 19-year-old Marie-Louise Mangot, who came from a

musical family from Lyon and was a good singer and instrumentalist. The couple would have four

children, two boys and two girls, and the marriage is said to have been a happy one.[11]

In spite of his fame as a music theorist, Rameau had trouble finding a post as an organist in

Paris.[12]

Later years, 17331764

Bust of Rameau by Caffieri, 1760

It was not until he was approaching 50 that Rameau decided to

embark on the operatic career on which his fame as a composer

mainly rests. He had already approached writer Houdar de la

Motte for a libretto in 1727, but nothing came of it; he was

finally inspired to try his hand at the prestigious genre of

tragdie en musique after seeing Montclair's Jepht in 1732.

Rameau's Hippolyte et Aricie premiered at the Acadmie

Royale de Musique on 1 October 1733. It was immediately

recognised as the most significant opera to appear in France

since the death of Lully, but audiences were split over whether

this was a good thing or a bad thing. Some, such as the

composer Andr Campra, were stunned by its originality and

wealth of invention; others found its harmonic innovations

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

4 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

discordant and saw the work as an attack on the French musical tradition. The two camps, the

so-called Lullyistes and the Rameauneurs, fought a pamphlet war over the issue for the rest of the

decade.[13]

Just before this time, Rameau had made the acquaintance of the powerful financier Alexandre Le

Riche de La Poupelinire, who became his patron until 1753. La Pouplinire's mistress (and later,

wife), Thrse des Hayes, was Rameau's pupil and a great admirer of his music. In 1731, Rameau

became the conductor of La Pouplinire's private orchestra, which was of an extremely high

quality. He held the post for 22 years; he was succeeded by Johann Stamitz and then Gossec.[14] La

Pouplinire's salon enabled Rameau to meet some of the leading cultural figures of the day,

including Voltaire, who soon began collaborating with the composer.[15] Their first project, the

tragdie en musique Samson, was abandoned because an opera on a religious theme by Voltairea

notorious critic of the Churchwas likely to be banned by the authorities.[16] Meanwhile, Rameau

had introduced his new musical style into the lighter genre of the opra-ballet with the highly

successful Les Indes galantes. It was followed by two tragdies en musique, Castor et Pollux

(1737) and Dardanus (1739), and another opra-ballet, Les ftes d'Hb (also 1739). All these

operas of the 1730s are among Rameau's most highly regarded works.[17] However, the composer

followed them with six years of silence, in which the only work he produced was a new version of

Dardanus (1744). The reason for this interval in the composer's creative life is unknown, although

it is possible he had a falling-out with the authorities at the Acadmie royale de la musique.[18]

The year 1745 was a watershed in Rameau's career. He received several commissions from the

court for works to celebrate the French victory at the Battle of Fontenoy and the marriage of the

Dauphin to Infanta Maria Teresa Rafaela of Spain. Rameau produced his most important comic

opera, Plate, as well as two collaborations with Voltaire: the opra-ballet Le temple de la gloire

and the comdie-ballet La princesse de Navarre.[19] They gained Rameau official recognition; he

was granted the title "Compositeur du Cabinet du Roi" and given a substantial pension.[20] 1745

also saw the beginning of the bitter enmity between Rameau and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Though

best known today as a thinker, Rousseau had ambitions to be a composer. He had written an opera,

Les muses galantes (inspired by Rameau's Indes galantes), but Rameau was unimpressed by this

musical tribute. At the end of 1745, Voltaire and Rameau, who were busy on other works,

commissioned Rousseau to turn La Princesse de Navarre into a new opera, with linking recitative,

called Les ftes de Ramire. Rousseau then claimed the two had stolen the credit for the words and

music he had contributed, though musicologists have been able to identify almost nothing of the

piece as Rousseau's work. Nevertheless, the embittered Rousseau nursed a grudge against Rameau

for the rest of his life.[21]

Rousseau was a major participant in the second great quarrel that erupted over Rameau's work, the

so-called Querelle des Bouffons of 175254, which pitted French tragdie en musique against

Italian opera buffa. This time, Rameau was accused of being out of date and his music too

complicated in comparison with the simplicity and "naturalness" of a work like Pergolesi's La serva

padrona.[22] In the mid-1750s, Rameau criticised Rousseau's contributions to the musical articles in

the Encyclopdie, which led to a quarrel with the leading philosophes d'Alembert and Diderot.[23]

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

5 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

As a result, Rameau became a character in Diderot's then-unpublished dialogue, Le neveu de

Rameau (Rameau's Nephew).

In 1753, La Pouplinire took a scheming musician, Jeanne-Thrse Goermans, as his mistress. The

daughter of harpsichord maker Jacques Goermans, she went by the name of Madame de SaintAubin, and her opportunistic husband pushed her into the arms of the rich financier. She had La

Pouplinire engage the services of the Bohemian composer Johann Stamitz, who succeeded

Rameau after a breach developed between Rameau and his patron; however, by then, Rameau no

longer needed La Pouplinire's financial support and protection.

Rameau pursued his activities as a theorist and composer until his death. He lived with his wife and

two of his children in his large suite of rooms in Rue des Bons-Enfants, which he would leave

every day, lost in thought, to take a solitary walk in the nearby gardens of the Palais-Royal or the

Tuileries. Sometimes he would meet the young writer Chabanon, who noted some of Rameau's

disillusioned confidential remarks: "Day by day, I'm acquiring more good taste, but I no longer

have any genius" and "The imagination is worn out in my old head; it's not wise at this age wanting

to practise arts that are nothing but imagination."[24]

Rameau composed prolifically in the late 1740s and early 1750s. After that, his rate of productivity

dropped off, probably due to old age and ill health, although he was still able to write another

comic opera, Les Paladins, in 1760. This was due to be followed by a final tragdie en musique,

Les Borades; but for unknown reasons, the opera was never produced and had to wait until the late

20th century for a proper staging.[25] Rameau died on 12 September 1764 after suffering from a

fever. He was buried in the church of St. Eustache, Paris the following day.[26]

Rameau's personality

While the details of his biography are vague and fragmentary, the

details of Rameau's personal and family life are almost completely

obscure. Rameau's music, so graceful and attractive, completely

contradicts the man's public image and what we know of his character

as described (or perhaps unfairly caricatured) by Diderot in his satirical

novel Le Neveu de Rameau. Throughout his life, music was his

consuming passion. It occupied his entire thinking; Philippe Beaussant

calls him a monomaniac. Piron explained that "His heart and soul were

in his harpsichord; once he had shut its lid, there was no one

home."[27] Physically, Rameau was tall and exceptionally thin,[28] as

can be seen by the sketches we have of him, including a famous

portrait by Carmontelle. He had a "loud voice." His speech was

difficult to understand, just like his handwriting, which was never

fluent. As a man, he was secretive, solitary, irritable, proud of his own

achievements (more as a theorist than as a composer), brusque with

those who contradicted him, and quick to anger. It is difficult to

imagine him among the leading wits, including Voltaire (to whom he

Portrait of Rameau by

Carmontelle, 1760

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

6 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

bears more than a passing physical resemblance[28]), who frequented La Pouplinire's salon; his

music was his passport, and it made up for his lack of social graces.

His enemies exaggerated his faults; e.g. his supposed miserliness. In fact, it seems that his

thriftiness was the result of long years spent in obscurity (when his income was uncertain and

scanty) rather than part of his character, because he could also be generous. We know that he helped

his nephew Jean-Franois when he came to Paris and also helped establish the career of ClaudeBnigne Balbastre in the capital. Furthermore, he gave his daughter Marie-Louise a considerable

dowry when she became a Visitandine nun in 1750, and he paid a pension to one of his sisters when

she became ill. Financial security came late to him, following the success of his stage works and

the grant of a royal pension (a few months before his death, he was also ennobled and made a

knight of the Ordre de Saint-Michel). But he did not change his way of life, keeping his worn-out

clothes, his single pair of shoes, and his old furniture. After his death, it was discovered that he only

possessed one dilapidated single-keyboard harpsichord[29] in his rooms in Rue des Bons-Enfants,

yet he also had a bag containing 1691 gold louis.[30]

Music

General character of Rameau's music

Nouvelles Suites de pices de

clavecin - Suite en la mineur

Gavotte et six doubles (6:47)

Rameau's music is characterised by the exceptional

technical knowledge of a composer who wanted

above all to be renowned as a theorist of the art.

I. Allemande (3:54)

Nevertheless, it is not solely addressed to the

intelligence, and Rameau himself claimed, "I try to

Performed in 1953 by Marcelle

conceal art with art." The paradox of this music was

Meyer

that it was new, using techniques never known

before, but it took place within the framework of

Problems playing these files? See media

old-fashioned forms. Rameau appeared

help.

revolutionary to the Lullyistes, disturbed by the

complex harmony of his music; and reactionary to the "philosophes," who only paid attention to its

content and who either would not or could not listen to the sound it made. The incomprehension he

received from his contemporaries stopped Rameau from repeating such daring experiments as the

second Trio des Parques in Hippolyte et Aricie, which he was forced to remove after a handful of

performances because the singers had been either unable or unwilling to render it correctly.

Rameau's musical works

Rameau's musical works may be divided into four distinct groups,[31] which differ greatly in

importance: a few cantatas; a few motets for large chorus; some pieces for solo harpsichord or

harpsichord accompanied by other instruments; and, finally, his works for the stage, to which he

dedicated the last thirty years of his career almost exclusively. Like most of his contemporaries,

Rameau often reused melodies that had been particularly successful, but never without

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

7 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

meticulously adapting them; they are not simple transcriptions. Besides, no borrowings have been

found from other composers, although his earliest works show the influence of other music.

Rameau's reworkings of his own material are numerous; e.g., in Les Ftes d'Hb, we find

L'Entretien des Muses, the Musette, and the Tambourin, taken from the 1724 book of harpsichord

pieces, as well as an aria from the cantata Le Berger Fidle.[32]

Motets

For at least 26 years, Rameau was a professional organist in the service of religious institutions, and

yet the body of sacred music he composed is exceptionally small and his organ works nonexistent.

Judging by the evidence, it was not his favourite field, but rather, simply a way of making

reasonable money. Rameau's few religious compositions are nevertheless remarkable and compare

favourably to the works of specialists in the area. Only four motets have been attributed to Rameau

with any certainty: Deus noster refugium, In convertendo, Quam dilecta, and Laboravi.[33]

Cantatas

The cantata was a highly successful genre in the early 18th century. The French cantata, which

should not be confused with the Italian or the German cantata, was "invented" in 1706 by the poet

Jean-Baptiste Rousseau[34] and soon taken up by many famous composers of the day, such as

Montclair, Campra, and Clrambault. Cantatas were Rameau's first contact with dramatic music.

The modest forces the cantata required meant it was a genre within the reach of a composer who

was still unknown. Musicologists can only guess at the dates of Rameau's six surviving cantatas,

and the names of the librettists are unknown.[35][36]

Instrumental music

Along with Franois Couperin, Rameau is one of the two masters of the French school of

harpsichord music in the 18th century. Both composers made a decisive break with the style of the

first generation of harpsichordists, who confined their compositions to the relatively fixed mould of

the classical suite. This reached its apogee in the first decade of the 18th century with successive

collections of pieces by Louis Marchand, Gaspard Le Roux, Louis-Nicolas Clrambault,

Jean-Franois Dandrieu, Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, Charles Dieupart, and Nicolas Siret.

Rameau and Couperin have different styles. They seem not to have known one another (Couperin

was one of the official court musicians while Rameau was still an unknown; fame would only come

to him after Couperin's death). Rameau published his first book of harpsichord pieces in 1706 while

Couperin (who was fifteen years his senior) waited until 1713 before publishing his first "ordres."

Rameau's music includes pieces in the pure tradition of the French suite: imitative ("Le rappel des

oiseaux," "La poule") and character ("Les tendres plaintes", "L'entretien des Muses") pieces and

works of pure virtuosity that resemble Scarlatti ("Les tourbillons," "Les trois mains") as well as

pieces that reveal the experiments of a theorist and musical innovator ("L'Enharmonique", "Les

Cyclopes"), which had a marked influence on Daquin, Royer, and Jacques Duphly. The suites are

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

8 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

grouped in the traditional way, by key.

Rameau's three collections appeared in 1706, 1724 and 1726 or 1727, respectively. After this, he

only composed a single piece for the harpsichord: "La Dauphine" (1747). Other works, such as

"Les petits marteaux," have been doubtfully attributed to him.

During his semiretirement in the years 1740 to 1744, he wrote the Pices de clavecin en concert

(1741), which some musicologists consider the pinnacle of French Baroque chamber music.

Adopting a formula successfully employed by Mondonville a few years earlier, these pieces differ

from trio sonatas in that the harpsichord is not simply there as basso continuo to accompany other

instruments (the violin, flute or viol) playing the melody but has an equal part in the "concert" with

them. Rameau also claimed that the pieces would be equally satisfying as solo harpsichord works

although this statement is far from convincing, since the composer took the trouble to transcribe

five of them himself those where the lack of other instruments would show the least.[37][38]

Opera

From 1733, Rameau dedicated himself almost exclusively to opera. On a strictly musical level,

18th-century French Baroque opera is richer and more varied than contemporary Italian opera,

especially in the place given to choruses and dances but also in the musical continuity that arises

from the respective relationships between the arias and the recitatives. Another essential difference:

whereas Italian opera gave a starring role to female sopranos and castrati, French opera had no use

for the latter. The Italian opera of Rameau's day (opera seria, opera buffa) was essentially divided

into musical sections (da capo arias, duets, trios, etc.) and sections that were spoken or almost

spoken (recitativo secco). It was during the latter that the action progressed while the audience

waited for the next aria; on the other hand, the text of the arias was almost entirely buried beneath

music whose chief aim was to show off the virtuosity of the singer. Nothing of the kind is to be

found in French opera of the day; since Lully, the text had to remain comprehensiblelimiting

certain techniques such as the vocalise, which was reserved for special words such as gloire

("glory") or victoire ("victory"). A subtle equilibrium existed between the more and the less musical

parts: melodic recitative on the one hand and arias that were often closer to arioso on the other,

alongside virtuoso "ariettes" in the Italian style. This form of continuous music prefigures

Wagnerian drama even more than does the "reform" opera of Gluck.

Five essential components may be discerned in Rameau's operatic scores:

Pieces of "pure" music (overtures, ritornelli, music which closes scenes). Unlike the highly

stereotyped Lullian overture, Rameau's overtures show an extraordinary variety. Even in his

earliest works, where he uses the standard French model, Rameauthe born symphonist and

master of orchestrationcomposes novel and unique pieces. A few pieces are particularly

striking, such as the overture to Zas, depicting the chaos before the creation of the universe,

that of Pigmalion, suggesting the sculptor's chipping away at the statue with his mallet, or

many more conventional depictions of storms and earthquakes, as well perhaps as the

imposing final chaconnes of Les Indes galantes or Dardanus.

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

9 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

Dance music: the danced interludes, which were obligatory even in tragdie en musique,

allowed Rameau to give free rein to his inimitable sense of rhythm, melody, and

choreography, acknowledged by all his contemporaries, including the dancers themselves. [39]

This "learned" composer, forever preoccupied by his next theoretical work, also was one who

strung together gavottes, minuets, loures, rigaudons, passepieds, tambourins, and musettes by

the dozen. According to his biographer, Cuthbert Girdlestone, "The immense superiority of all

that pertains to Rameau in choreography still needs emphasizing," and the German scholar

H.W. von Walthershausen affirmed:

Rameau was the greatest ballet composer of all times. The genius of his creation rests on

one hand on his perfect artistic permeation by folk-dance types, on the other hand on the

constant preservation of living contact with the practical requirements of the ballet

stage, which prevented an estrangement between the expression of the body from the

spirit of absolute music.[40]

Choruses: Padre Martini, the erudite musicologist who corresponded with Rameau, affirmed

that "the French are excellent at choruses," obviously thinking of Rameau himself. A great

master of harmony, Rameau knew how to compose sumptuous choruseswhether monodic,

polyphonic, or interspersed with passages for solo singers or the orchestraand whatever

feelings needed to be expressed.

Arias: less frequent than in Italian opera, Rameau nevertheless offers many striking examples.

Particularly admired arias include Tlare's "Tristes apprts," from Castor et Pollux; " jour

affreux" and "Lieux funestes," from Dardanus; Huascar's invocations in Les Indes galantes;

and the final ariette in Pigmalion. In Plate we encounter a showstopping ars poetica aria for

the character of La Folie (the madness), "Formons les plus brillants concerts / Aux langeurs

d'Apollon".

Recitative: much closer to arioso than to recitativo secco. The composer took scrupulous care

to observe French prosody and used his harmonic knowledge to give expression to his

protagonists' feelings.

During the first part of his operatic career (17331739), Rameau wrote his great masterpieces

destined for the Acadmie royale de musique: three tragdies en musique and two opra-ballets

that still form the core of his repertoire. After the interval of 1740 to 1744, he became the official

court musician, and for the most part, composed pieces intended to entertain, with plenty of dance

music emphasising sensuality and an idealised pastoral atmosphere. In his last years, Rameau

returned to a renewed version of his early style in Les Paladins and Les Borades.

His Zoroastre was first performed in 1749. According to one of Rameau's admirers, Cuthbert

Girdlestone, this opera has a distinctive place in his works: "The profane passions of hatred and

jealousy are rendered more intensely [than in his other works] and with a strong sense of reality."

Rameau and his librettists

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

10 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

Unlike Lully, who collaborated with Philippe Quinault on almost all his operas, Rameau rarely

worked with the same librettist twice. He was highly demanding and bad-tempered, unable to

maintain longstanding partnerships with his librettists, with the exception of Louis de Cahusac,

who collaborated with him on several operas, including Les ftes de l'Hymen et de l'Amour (1747),

Zas (1748), Nas (1749), Zoroastre (1749; revised 1756), La naissance d'Osiris (1754), and

Anacron (the first of Rameau's operas by that name, 1754). He is also credited with writing the

libretto of Rameau's final work, Les Borades (c. 1763).

Many Rameau specialists have regretted that the collaboration with Houdar de la Motte never took

place, and that the Samson project with Voltaire came to nothing because the librettists Rameau did

work with were second-rate. He made his acquaintance of most of them at La Pouplinire's salon, at

the Socit du Caveau, or at the house of the Comte de Livry, all meeting places for leading cultural

figures of the day.

Not one of his librettists managed to produce a libretto on the same artistic level as Rameau's

music: the plots were often overly complex or unconvincing. But this was standard for the genre,

and is probably part of its charm. The versification, too, was mediocre, and Rameau often had to

have the libretto modified and rewrite the music after the premiere because of the ensuing criticism.

This is why we have two versions of Castor et Pollux (1737 and 1754) and three of Dardanus

(1739, 1744, and 1760).

Reputation and influence

By the end of his life, Rameau's music had come under attack in France from theorists who

favoured Italian models. However, foreign composers working in the Italian tradition were

increasingly looking towards Rameau as a way of reforming their own leading operatic genre,

opera seria. Tommaso Traetta produced two operas setting translations of Rameau libretti that

show the French composer's influence, Ippolito ed Aricia (1759) and I Tintaridi (based on Castor et

Pollux, 1760).[41] Traetta had been advised by Count Francesco Algarotti, a leading proponent of

reform according to French models; Algarotti was a major influence on the most important

"reformist" composer, Christoph Willibald Gluck. Gluck's three Italian reform operas of the

1760sOrfeo ed Euridice, Alceste, and Paride ed Elenareveal a knowledge of Rameau's works.

For instance, both Orfeo and the 1737 version of Castor et Pollux open with the funeral of one of

the leading characters who later comes back to life.[42] Many of the operatic reforms advocated in

the preface to Gluck's Alceste were already present in Rameau's works. Rameau had used

accompanied recitatives, and the overtures in his later operas reflected the action to come,[43] so

when Gluck arrived in Paris in 1774 to produce a series of six French operas, he could be seen as

continuing in the tradition of Rameau. Nevertheless, while Gluck's popularity survived the French

Revolution, Rameau's did not. By the end of the 18th century, his operas had vanished from the

repertoire.[44]

For most of the 19th century, Rameau's music remained unplayed, known only by reputation.

Hector Berlioz investigated Castor et Pollux and particularly admired the aria "Tristes apprts," but

"whereas the modern listener readily perceives the common ground with Berlioz' music, he himself

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

11 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

was more conscious of the gap which separated them."[45] French humiliation in the FrancoPrussian War brought about a change in Rameau's fortunes. As Rameau biographer J. Malignon

wrote, "...the German victory over France in 187071 was the grand occasion for digging up great

heroes from the French past. Rameau, like so many others, was flung into the enemy's face to

bolster our courage and our faith in the national destiny of France."[46] In 1894, composer Vincent

d'Indy founded the Schola Cantorum to promote French national music; the society put on several

revivals of works by Rameau. Among the audience was Claude Debussy, who especially cherished

Castor et Pollux, revived in 1903: "Gluck's genius was deeply rooted in Rameau's works... a

detailed comparison allows us to affirm that Gluck could replace Rameau on the French stage only

by assimilating the latter's beautiful works and making them his own." Camille Saint-Sans (by

editing and publishing the Pices in 1895) and Paul Dukas were two other important French

musicians who gave practical championship to Rameau's music in their day, but interest in Rameau

petered out again, and it was not until the late 20th century that a serious effort was made to revive

his works. Over half of Rameau's operas have now been recorded, in particular by conductors such

as John Eliot Gardiner, William Christie, and Marc Minkowski.

Theoretical works

Treatise on Harmony, 1722

Rameau's 1722 Treatise on Harmony initiated a revolution in

music theory.[47] Rameau posited the discovery of the

"fundamental law" or what he referred to as the "fundamental

bass" of all Western music. Rameau's methodology incorporated

mathematics, commentary, analysis and a didacticism that was

specifically intended to illuminate, scientifically, the structure

and principles of music. He attempted to derive universal

harmonic principles from natural causes.[48] Previous treatises

on harmony had been purely practical; Rameau added a

philosophical dimension,[49] and the composer quickly rose to

prominence in France as the "Isaac Newton of Music."[50] His

fame subsequently spread throughout all Europe, and his

Treatise became the definitive authority on music theory,

forming the foundation for instruction in western music that

persists to this day.

List of works

RCT numbering refers to Rameau Catalogue

Thmatique established by Sylvie Bouissou and

Denis Herlin.[51]

Title page of the Treatise on

Harmony

Gavotte and Variations

Gavotte and Variations (1)

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

12 of 18

Instrumental works

Pices de clavecin.

Trois livres.

"Pieces for

harpsichord", 3

books, published

1706, 1724,

1726/27(?).

Tambourin

RCT 1

Premier livre

de Clavecin

(1706)

RCT 2

Pices de

clavecin

(1724) Suite

in E minor

RCT 3

Pices de

clavecin

(1724) Suite

in D major

RCT 4

Pices de

clavecin

(1724)

Menuet in C

major

RCT 5

Nouvelles

suites de

pices de

clavecin

(1726/27)

Suite in A

minor

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

Gavotte and Variations (2)

RCT 6

Nouvelles

suites de

pices de

clavecin

(1726/27)

Suite in G

Pieces de Clavecin

en Concerts Five

albums of character

pieces for

harpsichord, violin

and viol. (1741)

RCT 7

Concert I in C

minor

RCT 8

Concert II in

G major

RCT 9

Concert III in

A major

RCT 10

Concert IV in

B flat major

RCT 11

Concert V in

D minor

RCT 12 La

Dauphine for

harpsichord. (1747)

RCT 12bis Les

petits marteaux for

harpsichord.

Several orchestral

dance suites

extracted from his

operas.

Gavotte and Variations (3)

Gavotte and Variations (4)

Gavotte and Variations (5)

Gavotte and Variations (6)

Problems playing these files? See media

help.

Motets

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

13 of 18

RCT 13 Deus noster refugium

(c.17131715)

RCT 14 In convertendo (probably before

1720, rev. 1751)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

RCT 15 Quam dilecta (c. 17131715)

RCT 16 Laboravi (published in the

Trait de l'harmonie, 1722)

Canons

RCT 17 Ah! loin de rire, pleurons

(soprano, alto, tenor, bass) (pub. 1722)

RCT 18 Avec du vin, endormons-nous (2

sopranos, Tenor) (1719)

RCT 18bis L'pouse entre deux draps (3

sopranos) (formerly attributed to Franois

Couperin)

RCT 18ter Je suis un fou Madame (3

voix gales) (1720)

RCT 19 Mes chers amis, quittez vos

rouges bords (3 sopranos, 3 basses) (pub.

1780)

RCT 20 Rveillez-vous, dormeur sans fin

(5 voix gales) (pub. 1722)

RCT 20bis Si tu ne prends garde toi (2

sopranos, bass) (1720)

Songs

RCT 21.1 L'amante proccupe or A

l'objet que j'adore (soprano, continuo)

(1763)

RCT 21.2 Lucas, pour se gausser de

nous (soprano, bass, continuo) (pub. 1707)

RCT 21.3 Non, non, le dieu qui sait

aimer (soprano, continuo) (1763)

RCT 21.4 Un Bourbon ouvre sa carrire

or Un hros ouvre sa carrire (alto,

continuo) (1751, air belonging to Acante

et Cphise but censored before its first

performance and never reintroduced in the

work).

Cantatas

RCT 23 Aquilon et Orithie (between

1715 and 1720)[52]

RCT 28 Thtis (same period)

RCT 26 Limpatience (same period)

RCT 22 Les amants trahis (around 1720)

RCT 27 Orphe (same period)

RCT 24 Le berger fidle (1728)

RCT 25 Cantate pour le jour de la Saint

Louis (1740)

Operas and stage works

Tragdies en musique

RCT 43 Hippolyte et Aricie (1733;

revised 1742 and 1757)

RCT 32 Castor et Pollux (1737; revised

1754)

RCT 35 Dardanus (1739; revised 1744

and 1760), score

(http://www.library.unt.edu/music/assets

/vrbr/Rameau1744.pdf)

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

14 of 18

RCT 62 Zoroastre (1749; revised 1756,

with new music for Acts II, III & V)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

RCT 31 Les Borades or Abaris

(unperformed; in rehearsal 1763)

Opra-ballets

RCT 44 Les Indes galantes (1735;

revised 1736)

RCT 41 Les ftes d'Hb or les Talens

Lyriques (1739)

RCT 39 Les ftes de Polymnie (1745)

RCT 59 Le temple de la gloire (1745;

revised 1746)

RCT 38 Les ftes de l'Hymen et de

l'Amour or Les Dieux d'Egypte (1747)

RCT 58 Les surprises de l'Amour (1748;

revised 1757)

Pastorales hroques

RCT 60 Zas (1748)

RCT 49 Nas (1749)

RCT 29 Acante et Cphise or La

sympathie (1751)

RCT 34 Daphnis et Egl (1753)

Comdies lyriques

RCT 53 Plate or Junon jalouse (1745),

score (http://www.library.unt.edu/music

/assets/vrbr/Rameau.pdf)

RCT 51 Les Paladins or Le Vnitien

(1760)

Comdie-ballet

RCT 54 La princesse de Navarre (1744)

Actes de ballet

RCT 33 Les courses de Temp (1734)

RCT 40 Les ftes de Ramire (1745)

RCT 52 Pigmalion (1748)

RCT 42 La guirlande or Les fleurs

enchantes (1751)

RCT 57 Les sibarites or Sibaris (1753)

RCT 48 La naissance d'Osiris or La Fte

Pamilie (1754)

RCT 30 Anacron (1754)

RCT 58 Anacron (completely different

work from the above, 1757, 3rd Entre of

Les surprises de l'Amour)

RCT 61 Zphire (date unknown)

RCT 50 Nle et Myrthis (date

unknown)

RCT 45 Io (unfinished, date unknown)

Lost works

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

15 of 18

RCT 56 Samson (tragdie en musique)

(first version written 1733-1734; second

version 1736; neither were ever staged )

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

RCT 46 Linus (tragdie en musique)

(1751, score stolen after a rehearsal)

RCT 47 Lisis et Dlie (pastorale)

(scheduled on November 6, 1753)

Incidental music for opras comiques

Music mostly lost.

RCT 36 L'endriague (in 3 acts, 1723)

RCT 37 L'enrlement d'Arlequin (in 1

act, 1726)

RCT 55 La robe de dissension or Le faux

prodige (in 2 acts, 1726)

RCT 55bis La rose or Les jardins de

l'Hymen (in a prologue and 1 act, 1744)

Writings

Trait de l'harmonie rduite ses

principes naturels (Paris, 1722)

Nouveau systme de musique thorique

(Paris, 1726)

Dissertation sur les diffrents mthodes

d'accompagnement pour le clavecin, ou

pour l'orgue (Paris, 1732)

Gnration harmonique, ou Trait de

musique thorique et pratique (Paris,

1737)

Mmoire o l'on expose les fondemens du

Systme de musique thorique et pratique

de M. Rameau (1749)

Dmonstration du principe de l'harmonie

(Paris, 1750)

Nouvelles rflexions de M. Rameau sur sa

'Dmonstration du principe de l'harmonie'

(Paris, 1752)

Observations sur notre instinct pour la

musique (Paris, 1754)

Erreurs sur la musique dans

l'Encyclopdie (Paris, 1755)

Suite des erreurs sur la musique dans

l'Encyclopdie (Paris, 1756)

Reponse de M. Rameau MM. les editeurs

de l'Encyclopdie sur leur dernier

Avertissement (Paris, 1757)

Nouvelles rflexions sur le principe sonore

(17589)

Code de musique pratique, ou Mthodes

pour apprendre la musique...avec des

nouvelles rflexions sur le principe sonore

(Paris, 1760)

Lettre M. Alembert sur ses opinions en

musique (Paris, 1760)

Origine des sciences, suivie d'un

controverse sur le mme sujet (Paris,

1762)

See also

Querelle des Bouffons

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

16 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

References

Notes

1. New Grove p. 243: "A theorist of European stature, he was also France's leading 18th-century

composer."

2. Girdlestone p. 14: "It is customary to couple him with Couperin as one couples Haydn with Mozart or

Ravel with Debussy."

3. Beaussant p. 21

4. Date of birth given by Chabanon in his loge de M. Rameau(1764)

5. New Grove pp. 207208

6. Girdlestone p. 3

7. Norbert Dufourcq, Le clavecin, p. 87

8. Girdlestone p. 7

9. New Grove

10. New Grove p. 215

11. Girdlestone p. 8

12. New Grove p. 217

13. New Grove p. 219

14. Girdlestone, p. 475

15. New Grove pp. 221223

16. New Grove p. 220

17. New Grove p. 256

18. Beaussant p. 18

19. New Grove pp. 228230

20. Girdlestone p. 483

21. New Grove p. 232

22. Viking p. 830

23. New Grove pp. 2368

24. Quoted in Beaussant p. 19

25. Viking p. 846

26. New Grove p. 240

27. Malignon p. 16

28. Girdlestone p. 513

29. Compare the inventories of Franois Couperin (one large harpsichord, three spinets and a portable

organ) and Louis Marchand (three harpsichords and three spinets) after their deaths.

30. Girdlestone p. 508

31. Apart from the pieces written for the Paris fairs, which haven't survived

32. Beaussant pp. 34043

33. New Grove pp. 246247

34. Girdlestone p. 55

35. New Grove pp. 2434

36. Girdlestone pp. 6371

37. Girdlestone pp. 1452

38. New Grove pp. 247255

39. According to the ballet master Gardel: "He divined what the dancers themselves did not know. We look

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

17 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

upon him rightly as our first master." Quoted by Girdlestone, p. 563.

40. Girdlestone p. 563

41. Viking pp. 111011

42. Girdlestone pp .2012

43. Girdlestone p. 554

44. New Grove p. 277

45. Hugh Macdonald The Master Musicians: Berlioz (1982) p. 184

46. Quoted by Graham Sadler in "Vincent d'Indy and the Rameau Oeuvres compltes: a case of forgery?",

Early Music, August 1993, p. 418

47. Christensen, Thomas (2002). The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. Cambridge University

Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-521-62371-5.

48. New Grove p. 278

49. Girdlestone p. 520

50. Christensen, Thomas (2002). The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. Cambridge University

Press. p. 759. ISBN 0-521-62371-5.

51. Bouissou,S. and Herlin, D., Jean-Philippe Rameau : Catalogue thmatique des uvres musicales (T. 1,

Musique instrumentale. Musique vocale religieuse et profane), CNRS dition et ditions de la BnF,

Paris 2007

52. All dates from Beaussant p. 83

Sources

Beaussant, Philippe, Rameau de A Z (Fayard, 1983)

Girdlestone, Cuthbert, Jean-Philippe Rameau: His Life and Work (Dover paperback edition,

1969)

Holden, Amanda, (Ed) The Viking Opera Guide (Viking, 1993)

Sadler, Graham, (Ed.), The New Grove French Baroque Masters (Grove/Macmillan, 1988)

F. Annunziata, Una Tragdie Lyrique nel Secolo dei Lumi. Abaris ou Les Borades di Jean

Philippe Rameau, https://www.academia.edu/6100318

External links

(en) Gavotte with Doubles (http://bach.nau.edu/Rameau

Wikimedia Commons

/GavotteDoubles.html) Hypermedia by Jeff Hall & Tim

has media related to

Smith at the BinAural Collaborative Hypertext

Jean-Philippe Rameau.

(http://bach.nau.edu/) Shockwave Player required

("Gavotte with Doubles" link NG)

Wikiquote has

quotations related to:

(en) jp.rameau.free.fr (http://jp.rameau.free.fr

Jean-Philippe Rameau

/jpr-map.htm) Rameau Le Site

(fr) musicologie.org (http://www.musicologie.org

/Biographies/rameau_jp.html) Biography, List of Works, bibliography, discography,

theoretical writings, in French

(en) Jean-Philippe Rameau / Discography (http://www.discographie-rameau.com)

Magnatune (http://magnatune.com/artists/albums/pinnock-rameau/) Les Cyclopes by Rameau

in on-line mp3 format (played by Trevor Pinnock)

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Jean-Philippe Rameau - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

18 of 18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Philippe_Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau (https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=8638) at

Find a Grave

Jean-Philippe Rameau, "L'Orchestre de Louis XV" Suites d'Orchestre, Le Concert des

Nations (http://www.classicalacarte.net/Fiches/9882.htm), dir. Jordi Savall, Alia Vox, AVSA

9882

Sheet music

Free scores by Jean-Philippe Rameau at the International Music Score Library Project

Free scores by Jean-Philippe Rameau in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

Rameau (http://www.mutopiaproject.org/cgibin/make-table.cgi?Composer=RameauJP) free

sheet music from the Mutopia Project

Retrieved from "https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jean-Philippe_Rameau&

oldid=741519710"

Categories: 1683 births 1764 deaths People from Dijon Baroque composers

Composers for harpsichord French classical composers French male classical composers

French music theorists French opera composers Burials at glise Saint-Eustache, Paris

French ballet composers Composers awarded knighthoods 18th-century classical composers

French male writers

This page was last modified on 28 September 2016, at 01:08.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional

terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit

organization.

10/4/2016 4:41 PM

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Beethoven Violin SonatasDokument4 SeitenBeethoven Violin SonatasAriel Perez100% (1)

- (Free Scores - Com) Orem Preston Ware Harmony Book For Beginners 96515Dokument152 Seiten(Free Scores - Com) Orem Preston Ware Harmony Book For Beginners 96515Saimir BogdaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jazz Piano Roadmap PDFDokument1 SeiteJazz Piano Roadmap PDFjlangsethNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World of The String QuartetDokument18 SeitenThe World of The String QuartetMalu SabarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ballet MecaniqueDokument115 SeitenBallet MecaniqueOsvaldo GliecaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feminism in Popular MusicDokument4 SeitenFeminism in Popular Musicasdf asdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beethoven FactsDokument7 SeitenBeethoven FactsAliyah SandersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jazz HarmonyDokument2 SeitenJazz HarmonyAnonymous pQHxE9Noch keine Bewertungen

- Misunderstanding GershwinDokument6 SeitenMisunderstanding GershwinClaudio MaioliNoch keine Bewertungen

- RIAM DMusPerf Dimitri Papadimitriou PDFDokument196 SeitenRIAM DMusPerf Dimitri Papadimitriou PDFCristobal HerreraNoch keine Bewertungen

- What You Need To Know: How To Create A Realistic, Balanced, and Detailed Orchestral MockupDokument29 SeitenWhat You Need To Know: How To Create A Realistic, Balanced, and Detailed Orchestral MockupmarcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Augmented Sixth Chord - WikipediaDokument40 SeitenAugmented Sixth Chord - WikipediaevanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organum 1. Etymology, Early UsageDokument2 SeitenOrganum 1. Etymology, Early UsageOğuz ÖzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compare and Contrast Styles of Bach and His Sons, C.P.E.Bach and Johann Christian BachDokument12 SeitenCompare and Contrast Styles of Bach and His Sons, C.P.E.Bach and Johann Christian BachbonnieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fantomas Omen Ave SataniDokument1 SeiteFantomas Omen Ave SataniDeris NougadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discuss Beethoven's Impact On The Music of The 19th Century. Provide Specific Examples of How Composers Were Influenced, And/or Found Their Own Path.Dokument7 SeitenDiscuss Beethoven's Impact On The Music of The 19th Century. Provide Specific Examples of How Composers Were Influenced, And/or Found Their Own Path.BrodyNoch keine Bewertungen

- DOMENICO SCARLATTI: A CONTRIBUTION TO OUR UNDERSTANDING OF HIS SONATAS THROUGH PERFORMANCE AND RESEARCH by Jacqueline Esther OgeilDokument178 SeitenDOMENICO SCARLATTI: A CONTRIBUTION TO OUR UNDERSTANDING OF HIS SONATAS THROUGH PERFORMANCE AND RESEARCH by Jacqueline Esther OgeilMaría Del Pilar Chanampe100% (1)

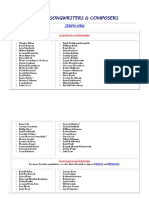

- Jewish Songwriters & ComposersDokument6 SeitenJewish Songwriters & ComposersPaulo LeònNoch keine Bewertungen

- Music Appreciation Final Exam Study Guide 10Dokument4 SeitenMusic Appreciation Final Exam Study Guide 10Chris AgudaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creating An Orchestral Room - Part - 1Dokument31 SeitenCreating An Orchestral Room - Part - 1Carlos Jr FernadezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ich Bin Der Welt Abhanden GekommenDokument43 SeitenIch Bin Der Welt Abhanden GekommenCETCoficialNoch keine Bewertungen

- RVW Journal 17Dokument28 SeitenRVW Journal 17plak78Noch keine Bewertungen

- Class 6 - French and Italian Music in The Fourteenth CenturyDokument3 SeitenClass 6 - French and Italian Music in The Fourteenth Centuryisabella perron100% (1)

- Annotated Bibliography - Music EvolutionDokument7 SeitenAnnotated Bibliography - Music EvolutionAndrew MajorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cadences in Music TheoryDokument5 SeitenCadences in Music TheoryGrantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Knew. Answers To Questions About Classical Music You Never Thought To Ask, 2016 - Robert A. Cutietta.Dokument353 SeitenWho Knew. Answers To Questions About Classical Music You Never Thought To Ask, 2016 - Robert A. Cutietta.Opeyemi ojoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gershwin-Concerto in FDokument2 SeitenGershwin-Concerto in FScott PriceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Twilight of Tonal SystemDokument19 SeitenTwilight of Tonal SystemFeiwan HoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manifesto (2015 Film) - ReferênciasDokument5 SeitenManifesto (2015 Film) - ReferênciasThiago GomezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saint-Saens Organ SymphonyDokument2 SeitenSaint-Saens Organ SymphonyMatthew LynchNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of Western Music Final Course Reduce Size PDFDokument282 SeitenHistory of Western Music Final Course Reduce Size PDFRimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Da Capo AriaDokument4 SeitenDa Capo AriachenamberNoch keine Bewertungen

- Czajkowski AML Music PHD 2018Dokument528 SeitenCzajkowski AML Music PHD 2018Estevan KühnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Henry Purcell (1659-1695) - The Fairy QueenDokument4 SeitenHenry Purcell (1659-1695) - The Fairy QueenPNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Voice of New MusicDokument294 SeitenThe Voice of New MusicJonathan CurleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Dictionary of Humourous Musical QuotationsDokument128 SeitenA Dictionary of Humourous Musical QuotationsJosé FernandesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aspects of American Musical Life AsDokument316 SeitenAspects of American Musical Life AsSoad KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tone ClusterDokument12 SeitenTone ClusterVictorSmerk100% (1)

- Bon Iver I Can T Make You Love MeDokument8 SeitenBon Iver I Can T Make You Love MeNery Kim0% (1)

- Lessons in Music Form: A Manual of AnalysisDokument117 SeitenLessons in Music Form: A Manual of AnalysisGutenberg.org88% (8)

- Who Needs Classical Music - Cultural Choice and Musical Value - J. Johnson (2002)Dokument151 SeitenWho Needs Classical Music - Cultural Choice and Musical Value - J. Johnson (2002)vladvaideanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solfege - Rhythm PatternsDokument2 SeitenSolfege - Rhythm PatternsEvangelia TsiaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- BerberianDokument329 SeitenBerberianMariaElisabettaTrupianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Needs Classical Music PDFDokument3 SeitenWho Needs Classical Music PDFAlin TrocanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clara Schumann NotesDokument2 SeitenClara Schumann NotesSusan DayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bartok's WorksDokument7 SeitenBartok's WorksfrankchinaskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Don Pasquale BilingüeDokument47 SeitenDon Pasquale Bilingüemadamina5812Noch keine Bewertungen

- Player Pianos SignificanceDokument9 SeitenPlayer Pianos SignificanceBrian LiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drum, Dance, Chant and SongDokument12 SeitenDrum, Dance, Chant and Songrazvan123456Noch keine Bewertungen

- MT0317 Scheme KS4 Conventions of PopDokument10 SeitenMT0317 Scheme KS4 Conventions of PopTracy LegassickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Film Music and Cross Genre PDFDokument129 SeitenFilm Music and Cross Genre PDFNisar A.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Giovanni Furno (1748-1837) Metodo Facile Breve e Chiara Ed Essensiali Regole Per Accompagnare Partimenti Senza NumeriDokument33 SeitenGiovanni Furno (1748-1837) Metodo Facile Breve e Chiara Ed Essensiali Regole Per Accompagnare Partimenti Senza NumeriHeyBoBHeHeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Some Music For The KalumbuDokument9 SeitenSome Music For The Kalumbuberimbau8Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mprovisation: A Pedagogical Method For Teaching Greater Expressivity and Musicality in String PlayingDokument4 SeitenMprovisation: A Pedagogical Method For Teaching Greater Expressivity and Musicality in String PlayingCésar Augusto HernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handels Horn and Trombone PartsDokument4 SeitenHandels Horn and Trombone Partsapi-425394984Noch keine Bewertungen

- Orchestration ToolkitDokument6 SeitenOrchestration ToolkitMatthew SuhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cage - Pataphysics Magazine Interview With John CageDokument3 SeitenCage - Pataphysics Magazine Interview With John Cageiraigne100% (1)

- Jean Philippe RameauDokument13 SeitenJean Philippe RameauBrandon McguireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jean-Philippe RameauDokument92 SeitenJean-Philippe RameauPaul Franklin Huanca AparicioNoch keine Bewertungen

- RameauDokument4 SeitenRameauLionel J. LewisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trust (Emotion) - WikipediaDokument12 SeitenTrust (Emotion) - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Temperance (Virtue) - WikipediaDokument5 SeitenTemperance (Virtue) - WikipediaDiana Ghius100% (1)

- Western Culture - WikipediaDokument30 SeitenWestern Culture - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Subjective Well-Being - WikipediaDokument13 SeitenSubjective Well-Being - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thought - WikipediaDokument9 SeitenThought - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shame - WikipediaDokument9 SeitenShame - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sorrow (Emotion) - WikipediaDokument3 SeitenSorrow (Emotion) - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self Confidence WikipediaDokument14 SeitenSelf Confidence WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self Interest WikipediaDokument2 SeitenSelf Interest WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tao Te Ching - WikipediaDokument12 SeitenTao Te Ching - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Søren Kierkegaard - WikipediaDokument63 SeitenSøren Kierkegaard - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schadenfreude - WikipediaDokument39 SeitenSchadenfreude - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Passion (Emotion) - WikipediaDokument8 SeitenPassion (Emotion) - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Regret - WikipediaDokument5 SeitenRegret - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saudade - WikipediaDokument8 SeitenSaudade - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scientific Method - WikipediaDokument38 SeitenScientific Method - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sadness - WikipediaDokument5 SeitenSadness - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remorse - WikipediaDokument6 SeitenRemorse - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resentment - WikipediaDokument5 SeitenResentment - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychomotor Agitation - WikipediaDokument3 SeitenPsychomotor Agitation - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pragmatism - WikipediaDokument29 SeitenPragmatism - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pleasure - WikipediaDokument7 SeitenPleasure - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pity - WikipediaDokument4 SeitenPity - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metaphysics - WikipediaDokument23 SeitenMetaphysics - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ontology - WikipediaDokument13 SeitenOntology - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Narcissism - WikipediaDokument22 SeitenNarcissism - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Observational Study - WikipediaDokument4 SeitenObservational Study - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modesty - WikipediaDokument16 SeitenModesty - WikipediaDiana GhiusNoch keine Bewertungen

- 05a-BSSOM - S13 - BSC ARCHITECTURE AND FUNCTIONS - 6-65894 - v6Dokument46 Seiten05a-BSSOM - S13 - BSC ARCHITECTURE AND FUNCTIONS - 6-65894 - v6azzou dino32Noch keine Bewertungen

- Top 5 Sport Books: Back To CNNDokument2 SeitenTop 5 Sport Books: Back To CNNdfsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Our MenuDokument8 SeitenOur MenueatlocalmenusNoch keine Bewertungen

- VGA To RGB+Sync ConverterDokument5 SeitenVGA To RGB+Sync ConverterntpckanihaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chicken BiriyaniDokument3 SeitenChicken BiriyaniTanmay RayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Viking Tales Sample Chapter PDFDokument9 SeitenViking Tales Sample Chapter PDFMariana Mariana0% (1)

- Videos Export 2020 February 01 0008Dokument405 SeitenVideos Export 2020 February 01 0008eynon100% (2)

- William Shakespeare QUOTESDokument2 SeitenWilliam Shakespeare QUOTESanon-39202100% (8)

- The Complete Guide To Creative Landscapes - Designing, Building and Decorating Your Outdoor Home (PDFDrive)Dokument324 SeitenThe Complete Guide To Creative Landscapes - Designing, Building and Decorating Your Outdoor Home (PDFDrive)One Architect100% (1)

- SAMPLE - (IMC Israel) : Hommage À György Ligeti IDokument3 SeitenSAMPLE - (IMC Israel) : Hommage À György Ligeti IJaime RayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cleaning Equipments: Types of BroomsDokument8 SeitenCleaning Equipments: Types of BroomsSushma MurthyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Governors v3Dokument30 SeitenGovernors v3nethmi100% (1)

- Cheat Code Age EmpiresDokument6 SeitenCheat Code Age Empiresabu_muhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Goods - 5% Services - 5%: Water Utilities - 2%Dokument27 SeitenGoods - 5% Services - 5%: Water Utilities - 2%Mari CrisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dsdhi LM55 F400 C4Dokument2 SeitenDsdhi LM55 F400 C4Manuel CastilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bridal Business PlanDokument16 SeitenBridal Business PlanFiker Er MarkNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Expansion Pack For M-Tron ProDokument7 SeitenAn Expansion Pack For M-Tron ProBlanko BrujoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boards 4chan OrgDokument17 SeitenBoards 4chan Orgthebigpotato1337Noch keine Bewertungen

- Quarter 4 Week 9 EnglishDokument54 SeitenQuarter 4 Week 9 EnglishJanine Jordan Canlas-BacaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Wonderful World of TheatreDokument5 SeitenThe Wonderful World of TheatreRAMIREZ, GIMELROSE T.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lets Go To The OnsenDokument32 SeitenLets Go To The OnsenMiguel Garcia100% (1)

- Universe Mode SVR 2011 & Cheat CodesDokument25 SeitenUniverse Mode SVR 2011 & Cheat CodesArchieAshishRaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Pasuc National Culture and The Arts Festival 2018: Philippine Association of State Universities and Colleges (Pasuc)Dokument33 Seiten10 Pasuc National Culture and The Arts Festival 2018: Philippine Association of State Universities and Colleges (Pasuc)Eulyn Remegio100% (1)

- The Edinburgh Introduction To Studying English LiteratureDokument248 SeitenThe Edinburgh Introduction To Studying English LiteratureLaura100% (2)

- Dona IndividualDokument3 SeitenDona IndividualAtletismo IbizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drunken MoogleDokument3 SeitenDrunken MoogletiyafijujNoch keine Bewertungen

- Food - Countable and Uncountable NounsDokument5 SeitenFood - Countable and Uncountable NounsKenny GBNoch keine Bewertungen

- x217 Crunchyroll 1 2Dokument12 Seitenx217 Crunchyroll 1 2Soy WidexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ulli Boegershausen-Hit The Road JackDokument4 SeitenUlli Boegershausen-Hit The Road JackeyeswideshoutNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Best A1 Unit 10 Reading TestDokument3 SeitenPersonal Best A1 Unit 10 Reading Testmaru lozanoNoch keine Bewertungen