Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

David Vs Arroyo

Hochgeladen von

RmLyn MclnaoOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

David Vs Arroyo

Hochgeladen von

RmLyn MclnaoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Macalinao, Romielyn P.

Subject: Constitutional Law 1

Topic: Legal Standing

Title:

PROF.

RANDOLF

DAVID

vs

GLORIA

MACAPAGAL-

ARROYO

Reference: G.R. No. 171396

May 3, 2006

FACTS

On February 24, 2006, as the nation celebrated the 20th

Anniversary of the Edsa People Power I, President Arroyo issued PP

1017 declaring a state of national emergency, thus:

NOW, THEREFORE, I, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, President of

the Republic of the Philippines and Commander-in-Chief of the

Armed Forces of the Philippines, by virtue of the powers vested

upon me by Section 18, Article 7 of the Philippine Constitution

which states that: The President. . . whenever it becomes

necessary, . . . may call out (the) armed forces to prevent or

suppress. . .rebellion. . ., and in my capacity as their

Commander-in-Chief, do hereby command the Armed Forces of

the Philippines, to maintain law and order throughout the

Philippines, prevent or suppress all forms of lawless violence as

well as any act of insurrection or rebellion and to enforce

obedience to all the laws and to all decrees, orders and

regulations promulgated by me personally or upon my direction;

and as provided in Section 17, Article 12 of the Constitution do

hereby declare a State of National Emergency.

On the same day, the President issued G. O. No. 5

implementing PP 1017.

Respondents stated that the proximate cause behind the

executive issuances was the conspiracy among some military

officers, leftist insurgents of the New Peoples Army (NPA), and

some members of the political opposition in a plot to unseat or

assassinate President Arroyo. They considered the aim to oust or

assassinate the President and take-over the reigns of government

as a clear and present danger.

ISSUES

Whether or not petitioners have legal standing?

RULINGS

Yes, all the petitioners have legal standing in view of the

transcendental importance of the issue involved.

It has been held that the person who impugns the validity of

a statute must have a personal and substantial interest in the case

such that he has sustained, or will sustain direct injury as a result.

Taxpayers, voters, concerned citizens, and legislators may be

accorded standing to sue, provided that the following requirements

are

met:

(a)the

cases

involve

constitutional

issues;

(b)for

taxpayers, there must be a claim of illegal disbursement of public

funds or that the tax measure is unconstitutional; (c)for voters,

there must be a showing of obvious interest in the validity of the

election law in question; (d)for concerned citizens, there must be a

showing that the issues raised are of transcendental importance

which must be settled early; and (e)for legislators, there must be a

claim that the official action complained of infringes upon their

prerogatives as legislators.

Being

mere

procedural

technicality,

however,

the

requirement of locus standi may be waived by the Court in the

exercise of its discretion. The question of locus standi is but

corollary to the bigger question of proper exercise of judicial power.

Undoubtedly, the validity of PP No. 1017 and G.O.

Locus standi is defined as a right of appearance in a court of

justice on a given question. In private suits, standing is governed

by the real-parties-in interest rule as contained in Section 2, Rule

3 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, as amended. It provides that

every action must be prosecuted or defended in the name of the

real party in interest. Accordingly, the real-party-in interest is

the party who stands to be benefited or injured by the judgment in

the suit or the party entitled to the avails of the suit. Succinctly

put, the plaintiffs standing is based on his own right to the relief

sought.

Case law in most jurisdictions now allows both citizen and

taxpayer standing in public actions. However, to prevent just

about any person from seeking judicial interference in any official

policy or act with which he disagreed with, and thus hinders the

activities of governmental agencies engaged in public service the

Supreme Court laid down the more stringent direct injury test. For

a private individual to invoke the judicial power to determine the

validity of an executive or legislative action, he must show that he

has sustained a direct injury as a result of that action, and it is not

sufficient that he has a general interest common to all members of

the public. However, being a mere procedural technicality, the

requirement of locus standi may be waived by the Court in the

exercise of its discretion in cases of transcendental importance and

far-reaching implications.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Pelaez Vs Auditor GeneralDokument52 SeitenPelaez Vs Auditor GeneralPam MiraflorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crespo vs. Provincial Board, 16 SCRA 66 (1988)Dokument3 SeitenCrespo vs. Provincial Board, 16 SCRA 66 (1988)Harold Q. Gardon100% (1)

- Case Digest - OBUS, MYRNA A.Dokument42 SeitenCase Digest - OBUS, MYRNA A.Myrna Angay Obus100% (1)

- ElecLaw - Romualdez-Marcos vs. Comelec, G.R. No. 119976 September 18, 1995Dokument2 SeitenElecLaw - Romualdez-Marcos vs. Comelec, G.R. No. 119976 September 18, 1995Lu CasNoch keine Bewertungen

- David Vs ArroyoDokument5 SeitenDavid Vs ArroyoPortia WynonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 265 Scra 61 G.R. No. 111651 Bustamante Vs NLRCDokument2 Seiten265 Scra 61 G.R. No. 111651 Bustamante Vs NLRCJun RinonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Javellana VDokument2 SeitenJavellana VJessie Marie dela PeñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nunez v. Sandiganbayan, 111 SCRA 433, G.R. 50581-50617Dokument23 SeitenNunez v. Sandiganbayan, 111 SCRA 433, G.R. 50581-50617ElieNoch keine Bewertungen

- DigestsDokument72 SeitenDigestsBrillantes VhieNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 171591Dokument18 SeitenG.R. No. 171591Renz Aimeriza AlonzoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 108998, August 24, 1994Dokument18 SeitenRepublic v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 108998, August 24, 1994KadzNituraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saguisag Et Al. v. Ochoa Et Al. (2016)Dokument3 SeitenSaguisag Et Al. v. Ochoa Et Al. (2016)Nicole WeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 208566 November 19, 2013 BELGICA vs. Honorable Executive Secretary Paquito N. Ochoa JR, Et Al, RespondentsDokument5 SeitenG.R. No. 208566 November 19, 2013 BELGICA vs. Honorable Executive Secretary Paquito N. Ochoa JR, Et Al, Respondents1222Noch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 56350. April 2, 1981 Digest (B)Dokument1 SeiteG.R. No. 56350. April 2, 1981 Digest (B)Maritoni RoxasNoch keine Bewertungen

- People v. Gasacao PDFDokument7 SeitenPeople v. Gasacao PDFRiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philips Industrial Development, Inc. vs. NLRC 210 SCRA 339Dokument14 SeitenPhilips Industrial Development, Inc. vs. NLRC 210 SCRA 339juan dela cruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public Corporation, Election, Admin Law Case DigestsDokument30 SeitenPublic Corporation, Election, Admin Law Case DigestsFaustine MataNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abakada Guro Party List v. ErmitaDokument3 SeitenAbakada Guro Party List v. ErmitaMikee MacalaladNoch keine Bewertungen

- 160 Pamatong Vs ComelecDokument2 Seiten160 Pamatong Vs ComelecJulius Geoffrey TangonanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Miranda v. Aguirre Full CaseDokument11 SeitenMiranda v. Aguirre Full CaseJaia Nicole Guevara TimoteoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Initia JRDokument3 SeitenInitia JRViner VillariñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Raquiza Vs Judge CastanedaDokument1 SeiteRaquiza Vs Judge CastanedaJonnifer QuirosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Domato-Togonon v. COA, G.R. No. 224516, July 6, 2021 (Parol Evidence Rule)Dokument20 SeitenDomato-Togonon v. COA, G.R. No. 224516, July 6, 2021 (Parol Evidence Rule)Aisaia Jay ToralNoch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs BandulaDokument2 SeitenPeople Vs BandulaCheza BiliranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest: Bayan V. Executive Secretary ErmitaDokument3 SeitenCase Digest: Bayan V. Executive Secretary ErmitakjsitjarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Morales vs. SubidoDokument5 SeitenMorales vs. SubidoAngelina Villaver ReojaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DelicadezaDokument7 SeitenDelicadezaromeo n bartolomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- International School Alliance of Educators Vs QuisumbingDokument6 SeitenInternational School Alliance of Educators Vs QuisumbingShane Marie CanonoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caunaca v. SalazarDokument3 SeitenCaunaca v. SalazarsanticreedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Macias vs. ComelecDokument1 SeiteMacias vs. ComelecKeziah HuelarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smart vs. NTCDokument3 SeitenSmart vs. NTCCDMNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Dolalas V OmbudsmanDokument3 Seiten4 Dolalas V Ombudsmanakonik22Noch keine Bewertungen

- Contract of LeaseDokument3 SeitenContract of LeaseSteve UyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jardeleza Vs SerenoDokument2 SeitenJardeleza Vs SerenoKang MinheeNoch keine Bewertungen

- DPL - 9 - NUÑEZ v. AVERIADokument1 SeiteDPL - 9 - NUÑEZ v. AVERIAHello123Noch keine Bewertungen

- FEU-Dr. Nicanor Reyes Medical Foundation, Inc. vs. Trajano, G. R. No. 76273, July 31, 1987Dokument5 SeitenFEU-Dr. Nicanor Reyes Medical Foundation, Inc. vs. Trajano, G. R. No. 76273, July 31, 1987Christian ArmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Facts:: Case Digest: Osmeña vs. Pendatun, 109 Phil 863 G.R. No. 17144, October 28, 1960Dokument1 SeiteFacts:: Case Digest: Osmeña vs. Pendatun, 109 Phil 863 G.R. No. 17144, October 28, 1960senpai FATKiDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Garces Vs Estenzo GR L-53487Dokument9 SeitenGarces Vs Estenzo GR L-53487Leomar Despi LadongaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legaspi Vs Civil Service CommisionDokument2 SeitenLegaspi Vs Civil Service CommisionJimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine British Assurance CoDokument3 SeitenPhilippine British Assurance CoLaw2019upto2024Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mahinay v. Court of AppealsDokument27 SeitenMahinay v. Court of AppealsPaulyn MarieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lambino V Comelec, 505 SCRA 160 (2007)Dokument107 SeitenLambino V Comelec, 505 SCRA 160 (2007)Ronna Athena PalomoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutory Construction Legal MaximsDokument4 SeitenStatutory Construction Legal MaximsErika Angela GalceranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Victoriano vs. Elizalde Rope Workers AssoDokument12 SeitenVictoriano vs. Elizalde Rope Workers AssoMaria Fiona Duran Merquita100% (1)

- Atienza Vs Saluta PDFDokument19 SeitenAtienza Vs Saluta PDFFritzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ang Tibay vs. CIR, 69 Phil 635 (1940)Dokument6 SeitenAng Tibay vs. CIR, 69 Phil 635 (1940)Harold Q. GardonNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Principles: Effect and Application of LawsDokument22 SeitenGeneral Principles: Effect and Application of LawsJing DalaganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest of Ayer Productions Vs CapulongDokument2 SeitenCase Digest of Ayer Productions Vs CapulongJustin Reden BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poli Rachelle Toledo V ComelecDokument3 SeitenPoli Rachelle Toledo V ComelecDyane Garcia-AbayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MILAGROS E vs. AmoresDokument3 SeitenMILAGROS E vs. AmoresJoyce Sumagang ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter of Assoc Justice Puno To The CADokument1 SeiteLetter of Assoc Justice Puno To The CAKathleen del RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- 78) Araro V ComelecDokument3 Seiten78) Araro V ComelecMav Esteban100% (1)

- De Venecia Vs SandiganbayanDokument3 SeitenDe Venecia Vs SandiganbayanRelmie TaasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor LawDokument3 SeitenLabor LawnaiveNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Re Almacen G.R. No. L-27654 (In The Matter of Proceedings For Disciplinary Action Against Atty. Vicente Raul Almacen vs. Virginia Yaptinchay)Dokument3 SeitenIn Re Almacen G.R. No. L-27654 (In The Matter of Proceedings For Disciplinary Action Against Atty. Vicente Raul Almacen vs. Virginia Yaptinchay)AlykNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aklat v. ComelecDokument1 SeiteAklat v. ComelecRodeo Roy Seriña DagohoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Villavicencio V LukbanDokument2 SeitenVillavicencio V LukbanEn Zo100% (1)

- People Vs BasillaDokument2 SeitenPeople Vs BasillaLouise Marie PomidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Estarija v. RanadaDokument14 SeitenEstarija v. RanadaJ. JimenezNoch keine Bewertungen

- David vs. MacapagalDokument3 SeitenDavid vs. MacapagalShira Mae GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of Discrepancy Baptismal Certificate Doc RHEA MAEDokument1 SeiteAffidavit of Discrepancy Baptismal Certificate Doc RHEA MAERmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- MANALO Vs CADokument2 SeitenMANALO Vs CARmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of Two Disinterested PersonsDokument1 SeiteAffidavit of Two Disinterested PersonsRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of Two Disinterested Persons (For Delayed Birth Cert)Dokument1 SeiteAffidavit of Two Disinterested Persons (For Delayed Birth Cert)RmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of Two Disinterested PersonsDokument1 SeiteAffidavit of Two Disinterested PersonsKarl PagzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Aid RA 9048 Form No Petition For Change of Entry in Birth CertDokument3 SeitenLegal Aid RA 9048 Form No Petition For Change of Entry in Birth CertRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CONSOLIDATED BANK AND TRUST CORP Vs CADokument2 SeitenCONSOLIDATED BANK AND TRUST CORP Vs CARmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SALVACION Vs CENTRAL BANKDokument2 SeitenSALVACION Vs CENTRAL BANKRmLyn Mclnao100% (1)

- Evidence CDsDokument73 SeitenEvidence CDsRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- BUSUEGO Vs CADokument2 SeitenBUSUEGO Vs CARmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Position Paper SampleDokument2 SeitenPosition Paper SampleRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporation Law DigestsDokument17 SeitenCorporation Law DigestsRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corpo Case Digest CompilationDokument16 SeitenCorpo Case Digest CompilationRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endorsement (Atty. Orcullo)Dokument1 SeiteEndorsement (Atty. Orcullo)RmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Overload LetterDokument1 SeiteOverload LetterRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Palanca Vs Fred WilsonDokument1 SeitePalanca Vs Fred WilsonRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01 CD Special ProceedingsDokument7 Seiten01 CD Special ProceedingsRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joint Affidavit (Heirs of Purita Patalinghug)Dokument1 SeiteJoint Affidavit (Heirs of Purita Patalinghug)RmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Draft Ordinance (Re-Titling of Positions)Dokument2 SeitenDraft Ordinance (Re-Titling of Positions)RmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- LAND TITLES - Forms&ContentsDokument27 SeitenLAND TITLES - Forms&ContentsRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elcano Vs HillDokument1 SeiteElcano Vs HillRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of Financial Support (Cencerita)Dokument1 SeiteAffidavit of Financial Support (Cencerita)RmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roque Vs Aguado DigestDokument2 SeitenRoque Vs Aguado DigestRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arlyn N. Umpad Sitio Sto. Nino, Quiot, Cebu City 09267715942Dokument3 SeitenArlyn N. Umpad Sitio Sto. Nino, Quiot, Cebu City 09267715942RmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- JEFFREY Garrido: Position Desired: Service CrewDokument3 SeitenJEFFREY Garrido: Position Desired: Service CrewRmLyn MclnaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Copyreading and Headline Writing Exercise 2 KeyDokument2 SeitenCopyreading and Headline Writing Exercise 2 KeyPaul Marcine C. DayogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Branch - QB Jan 22Dokument40 SeitenBranch - QB Jan 22Nikitaa SanghviNoch keine Bewertungen

- BDA Advises JAFCO On Sale of Isuzu Glass To Basic Capital ManagementDokument3 SeitenBDA Advises JAFCO On Sale of Isuzu Glass To Basic Capital ManagementPR.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hearing Committee On Environment and Public Works United States SenateDokument336 SeitenHearing Committee On Environment and Public Works United States SenateScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- SLB Qhse Standards & B.O.O.K.S - Poster - v03 - enDokument1 SeiteSLB Qhse Standards & B.O.O.K.S - Poster - v03 - enLuisfelipe Leon chavezNoch keine Bewertungen

- of GoldDokument22 Seitenof GoldPooja Soni100% (5)

- PNR V BruntyDokument21 SeitenPNR V BruntyyousirneighmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Friday Foreclosure List For Pierce County, Washington Including Tacoma, Gig Harbor, Puyallup, Bank Owned Homes For SaleDokument11 SeitenFriday Foreclosure List For Pierce County, Washington Including Tacoma, Gig Harbor, Puyallup, Bank Owned Homes For SaleTom TuttleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Method NIFTY Equity Indices PDFDokument130 SeitenMethod NIFTY Equity Indices PDFGita ThoughtsNoch keine Bewertungen

- PIP RFEG1000 Guidelines For Use of Refractory PracticesDokument5 SeitenPIP RFEG1000 Guidelines For Use of Refractory PracticesNicolasMontoreRosNoch keine Bewertungen

- US v. Esmedia G.R. No. L-5749 PDFDokument3 SeitenUS v. Esmedia G.R. No. L-5749 PDFfgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Godines vs. Court of AppealsDokument3 SeitenGodines vs. Court of AppealsTinersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Suraya Binti Hussin: Kota Kinabalu - T1 (BKI)Dokument2 SeitenSuraya Binti Hussin: Kota Kinabalu - T1 (BKI)Sulaiman SyarifuddinNoch keine Bewertungen

- OSHAD-SF - TG - Managament of Contractors v3.0 EnglishDokument18 SeitenOSHAD-SF - TG - Managament of Contractors v3.0 EnglishGirish GopalakrishnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDokument3 SeitenStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceHiten AhirNoch keine Bewertungen

- NSSF ActDokument38 SeitenNSSF Actokwii2839Noch keine Bewertungen

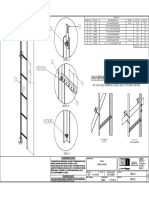

- WCL8 (Assembly)Dokument1 SeiteWCL8 (Assembly)Md.Bellal HossainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Credit, Background, Financial Check Disclaimer2Dokument2 SeitenCredit, Background, Financial Check Disclaimer2ldigerieNoch keine Bewertungen

- BLCTE - MOCK EXAM II With Answer Key PDFDokument20 SeitenBLCTE - MOCK EXAM II With Answer Key PDFVladimir Marquez78% (18)

- Financial Accounting Module 2Dokument85 SeitenFinancial Accounting Module 2paul ndhlovuNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACE Consultancy AgreementDokument0 SeitenACE Consultancy AgreementjonchkNoch keine Bewertungen

- The PassiveDokument12 SeitenThe PassiveCliver Rusvel Cari SucasacaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samyu AgreementDokument16 SeitenSamyu AgreementMEENA VEERIAHNoch keine Bewertungen

- In The Matter of The IBP 1973Dokument6 SeitenIn The Matter of The IBP 1973Nana SanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre Shipment and Post Shipment Finance: BY R.Govindarajan Head-Professional Development Centre-South Zone ChennaiDokument52 SeitenPre Shipment and Post Shipment Finance: BY R.Govindarajan Head-Professional Development Centre-South Zone Chennaimithilesh tabhaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Passport Application Form 19Dokument4 SeitenPassport Application Form 19Danny EphraimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Huge Filing Bill WhiteDokument604 SeitenHuge Filing Bill WhiteBen SellersNoch keine Bewertungen

- HyiDokument4 SeitenHyiSirius BlackNoch keine Bewertungen

- CESSWI BROCHURE (September 2020)Dokument2 SeitenCESSWI BROCHURE (September 2020)Ahmad MensaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avila V BarabatDokument2 SeitenAvila V BarabatRosana Villordon SoliteNoch keine Bewertungen