Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Japan After 3.11 - A Comparative Analysis of Human and State Security Issues

Hochgeladen von

Jorel ChanCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Japan After 3.11 - A Comparative Analysis of Human and State Security Issues

Hochgeladen von

Jorel ChanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Japan After 3.

11

A Comparative Analysis of Human and State Security Issues

Regarding Post-Fukushima Nuclear Restart Decisions

Prepared by

Jorel Chan

"Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood.

Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less."

Marie Curie

Japan After 3.11

Contents

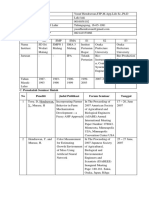

Abbreviations ................................................................................................................ 2

Background and Objectives .......................................................................................... 3

Research Methodology ................................................................................................. 4

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5

Human Security: Concerns of the Japanese People ...................................................... 8

The Basis for Fear: Historical Origin of Radiation Paranoia from Hiroshima ......... 9

The Consequence of Fear: Humanitarian Challenges in Fukushima ...................... 12

Preliminary Policy Proposition ............................................................................... 15

State Security: Interests of the Japanese Government ................................................ 17

Domestic Political Economy: The Inertia of the Nuclear Village .......................... 18

International Security: Interstate Relations and Japans Sovereignty ..................... 21

Final Revised Policy Proposition ............................................................................ 25

Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 30

Appendix..................................................................................................................... 33

Bibliography ............................................................................................................... 36

Japan After 3.11

Abbreviations

ANRE

Agency for Natural Resources and Energy

DPJ

Democratic Party of Japan

IAEA

International Atomic and Energy Agency

ICRP

International Commission on Radiological

Protection

LDP

Liberal Democratic Party

METI

Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry

MLIT

Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and

Tourism

MOE

Ministry of the Environment

MOF

Ministry of Finance

MOFA

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

NISA

Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency

NRA

Nuclear Regulation Authority

NSC

Nuclear Safety Commission

TEPCO

Tokyo Electric Power Company

UNDP

United Nations Development Programme

UNSCEAR

United Nations Scientific Committee on the

Effects of Atomic Radiation

Japan After 3.11

Background and Objectives

Written three years after 3.11, this paper aims to present a

comparative analysis of both human security concerns and state

security interests after the 3.11 Fukushima disaster, arguing against

a total shutdown and decommission of nuclear plants in Japan, and

proposing a policy involving nuclear restarts justified on grounds

of state security and which likewise takes into account human

security issues correspondingly.

Japan After 3.11

Research Methodology

In addition to the various books, journals, articles, official

reports and other academic sources used for research, an

independent fact-finding humanitarian mission was undertaken in

the summer of 2014 to the different parts of Japan affected by the

3.11 disaster. For the sake of brevity, the relevant research obtained

during this trip which are referenced in this paper includes: a

research presentation by Professor Tanigaki Minoru of Kyoto

Research Reactor Institute and two interviews conducted with Ms.

Yui Hamada of Nozomi Center and with Ms. Minako Takahashi of

Fukushima Matsushimaya Ryokan. Excerpts can be found in the

appendix. Full original audio tapes, transcriptions and translations

are available upon request.

Japan After 3.11

I

Introduction

More than three years since the 3.11 earthquake and tsunami

struck off the Pacific coast of Japan, the aftershocks of the

Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Plant Incident are still being felt.

While infrastructural recovery has been steadily underway for

those hit by the natural disasters, the present situation for those

refugees affected by the nuclear disaster remains bleak, their

uncertainties only exacerbating with each passing year. Yet, at this

point in time, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is already

taking concrete steps to begin restarting nuclear plants, which had

all been shut down after the disaster, in order to alleviate energy

demands of the worlds third largest economy. Now, presented

with such a stark contrast in humanitarian circumstances and state

action, one would almost be compelled to question whether the

Japanese government has truly learnt anything from the 3.11

disaster. Hence, in order to understand the policy decisions that

need to be made at this juncture, this paper seeks to present a

comparative analysis between human security concerns and state

security interests, investigating what each of them specifically

entail in the context of Japan, and through their fundamentally

crucial relationship state security as guarantor of the imperative

pursuit for human security critically examine if differences in

their respective visions can ultimately be reconciled in a

consolidated and negotiated policy response.

Human Security as an Imperative:

Freedom from Fear and Disaster Recovery

Regarding human security approaches, the final policy

proposition of this paper focuses on achieving two main elements

according to the 1994 UNDP Human Development Report (HDR),

namely: (1) human security is easier to ensure through early

prevention than later intervention, and (2) human security is

people-centred (UNDP 1994: 22-3). Recognising that the role of

the state is to be responsible for its citizens lives, the idea of

people-centredness grounds human security as an imperative goal

5

Japan After 3.11

to which all democratic governments must endeavour. With this in

mind, we begin our examination by employing HDRs freedom

from fear (UNDP 1994: 24) strategy, with fear in this case defined

relevantly for the 3.11 context. By identifying the basis for fear as

radiation paranoia due to the publics unscientific

misunderstanding between nuclear energy technologies and nuclear

weapon consequences, a misunderstanding which originated from

a historical conflation with pacifism ever since the Hiroshima and

Nagasaki atomic bombings, it appears that an anti-nuclear policy to

decommission all nuclear plants would seem to be an effective

preventive measure. However, when we consider the context of

Japan now after 3.11 where human security breaches have already

occurred, resulting in psychological and sociological problems

constituting the disaster recovery challenges presently faced by

refugees, we recognise that achieving human security requires not

only prevention but also immediate intervention, hereby

elucidating the insufficiency of such anti-nuclear policy.

State Security as a Guarantor:

Domestic Politics and Structural Realism

Yet, the insufficiency of anti-nuclear policy is not reason

enough to abrogate it; we need to argue for its impossibility. The

inverse decision in favour of nuclear restarts is argued on grounds

of first requiring a guarantor for human security, of which state

security provides and will be, in this paper, best explained via a

structural realist approach. Realism proves too simplistic in this

case as it does not understand that policy is the outcome of a

complex political process; therefore structural realism is required

to emphasise structural factors whilst allowing for their mediation

through domestic political processes (Kitchen 2010: 118). By

looking at the domestic political structure of the nuclear village in

Japan which involves both powerful non-state actors such as pronuclear energy firms with the capabilities to influence state policy,

as well as the incumbent state administrators in place that stabilises

a complex bureaucratic structure that resists significant policy

overhaul, we understand that this constitutes the national system

of political economy (Gilpin 2001: 18) upon which Japanese

economic and security policies then hinge. Accordingly, emerging

as an outcome of international structure, domestic factors and of a

complex interaction between the two (Liu and Zhang 2006),

Japans foreign policy seeks to maximise capabilities within the

6

Japan After 3.11

regional security configuration with the US against Chinas rise,

and minimise constraints by leveraging on Kenji Gotos death to

justify greater trade with Middle East export partners while

diversifying energy sources, policies of which are all made

possible through nuclear technology and restarts, for the sake of

state security.

Guarantor of the Imperative

In the Commission on Human Security (CHS), it is

acknowledged that human security reinforces state security but

does not replace it (CHS 2003: 4-6), yet it does not mean that

human security is of any less importance. Without a sovereign state

to belong to, we may not have the chance to even speak of human

security issues; but without always concerning ourselves with the

ordinary individual, our relentless pursuit for statehood would be

pyrrhic at best. State security is the means to which human security

is an ends that all governments ought to seek; state security is the

fundamental guarantor of the chief imperative pursuit for human

security. Hence, even while choosing to restart nuclear plants for

the sake of state security, human security strategies still can and

ought to be pursued to prevent public fears, mitigate present

humanitarian challenges and reduce disaster risk of future

vulnerabilities in Japan. It is to this end that we begin our first

investigations into human security.

Japan After 3.11

II

Human Security: Concerns of the

Japanese People

In this chapter, we shall be investigating the human security

concerns within the context of Fukushima via the theoretical

framework of UNDPs freedom from fear concept. Before we can

begin to analyse the policy rationale behind the decision to shut

down nuclear plants, we need to begin by identifying the

imperative need of pursuing freedom from fear to achieve human

security for the people. The chapter hence begins by first

addressing this primary overarching question: why is there a need

to free these people from fear? To this end, we proceed to unpack

the relevant justifications by examining what exactly this notion of

fear comprises in this nuclear discourse, and consequently, what

ramifications this fear has on human security such that it warrants

policy action that is aimed at providing the people with a freedom

from fear.

This is rephrased into the two secondary questions that

sequentially structure our arguments in this chapter: firstly, what is

the basis for this fear prevalent in Fukushima? This section will

argue that the genesis of this radiation paranoia can be traced

historically to the Hiroshima atomic bombings, and that the pursuit

of freedom from fear is imperative because this radiation

paranoia has been falsely correlated with pacifist political agenda,

resulting in scientifically unfounded beliefs prevalent amongst the

Japanese public.

Recognising such prevalence of radiation paranoia in

Fukushima, we then ask secondly, what are the consequences of

fear in the affected local and refugee communities? We shall argue

that such consequences on health security are psychological rather

than biological, resulting in present and immediate disaster

recovery challenges such as psychiatric disorders and social

problems. Precisely then, because the basis of fear is unnecessary,

and its consequences urgent, the imperative to pursue a disaster

8

Japan After 3.11

recovery strategy as well as freedom from fear is justified in

order to achieve human security.

With this framework of justifications in place, we can now

proceed to analyse whether or not the anti-nuclear decision is

indeed an appropriate policy to achieve freedom from fear. The

fundamental argument for human security here is as follows: the

presence of nuclear plants is a cause for fear for the people in Japan,

so if we eliminate the object of fear through a policy of keeping

nuclear plants shut down, it follows that there will be no more risk

of nuclear disasters and the people will be free from radiation fear,

thereby achieving human security. While logically valid as an

argument, this policy action is nonetheless problematic as this

limits the consideration of other policy possibilities to which

freedom from fear can be achieved as well, but more importantly,

as will constitute our next main argument in the succeeding chapter,

the fact that the inverse policy that is, of restart nuclear plants is

fundamental as guarantor for the state to even pursue human

security policies.

The Basis for Fear:

Historical Origin of Radiation Paranoia from Hiroshima

In this section, we shall argue for a freedom from fear

strategy as part of achieving human security, because the basis of

such fear, prevalent amongst the Japanese people throughout

modern Japanese history, is deeply entrenched in pacifist antinuclear political agenda and is fundamentally also scientifically

unfounded. These shall be examined by looking at the 1945 atomic

bombings, an important political event which had set the precedent

accordingly for pacifist political interests against nuclear weapons

to be mixed in and often conflated with other forms of non-hostile

nuclear activities such as nuclear reactors; this constitutes an

equivocation because of differences between relevant vested

interests as well as the respective technologies behind nuclear

weapon proliferation and nuclear power usage. Hence, by

undiscerningly superimposing the radiation consequences from the

aftermath of nuclear bombings onto the effects of a nuclear plant

meltdown such as in the case of Fukushima, we realise that the

present paranoia in Fukushima is a product of historically political

and scientific misinformation.

Japan After 3.11

Anti-nuclear Movements and Political Pacifism

As the first and only usage of nuclear weapons for warfare in

modern world history since, the 1945 atomic bombings of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which marked the end of WWII and took

hundreds of thousands of Japanese lives, played a key role in

ushering in modern Japan, with its unique Peace Constitution

which was to see the rebirth of Japan out of destruction (Momose

2010: 117), eventually serving as the historical cornerstone and

precursor of its anti-nuclear pacifism (Kim 2008: 61). While these

worldwide anti-nuclear pacifist movements have greatly

contributed towards international nuclear arms disarmament efforts

(Wittner 2004), the coalescent nature of anti-nuclear politics

together with political pacifism, while complementary during the

Cold War when nuclear holocaust was a real possibility, meant also

that the pursuit of both ideals of world peace and a nuclear-free

world was often articulated in tandem; this eventually became

problematic as the international political situation changed.

Especially ever since Eisenhowers historic call to facilitate the

development of peaceful use of atomic power (Eisenhower 1953)

and the subsequent formation of IAEA, there was to be observed

an eventual divergence between pacifism and anti-nuclear agenda;

governments had begun shifting their interests to pursue nuclear

power away from military or traditional security purposes towards

peacetime economic and energy infrastructural development.

However, due to the sensitivity of classified government

intelligence which had surrounded nuclear-related information

during the Cold War, such technical distinctions between nuclear

weaponry and nuclear power generation had not been adequately

explained to the public masses and grassroots, of which antinuclear pacifist movements generally comprise. Radiation fears,

associated with the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

that resulted in many lives lost in the immediate explosive

detonation and more due to subsequent radiation poisoning, had

been conflated by grassroots anti-nuclear activists with the

Fukushima disaster, which had no detonation and has yet to result

in subsequent radiation-related deaths. Around the world,

Hiroshima and Nagasaki are constantly re-remembered, but now

through the prism of Fukushima (Mackie 2015), albeit

inaccurately, only because both equivocally involve radiation but

employ very different intent and methods of utilising nuclear

energy. What had originally been a clarion call for a nuclear free10

Japan After 3.11

world originating from a fear of nuclear weaponry that has

intentionally caused deaths, has quietly rebranded itself to

condemn a peacetime incident that has no lethal intent nor claimed

any lives, but which ironically is at present seeing an escalating

refugee death toll precisely because of this conflated condemnation

that has resulted in the perpetuation of severe misinformation and

radiation paranoia in Fukushima.

The Hiroshima Syndrome and Unscientific Beliefs

Having explained that the contextual differences between

Hiroshima and Fukushima are legitimate and that the beliefs about

radiation harboured by the public is truly misinformed, it would be

remiss for us to merely state that the public is wrong by sole virtue

of differences existing; we need to examine how exactly they are

different through the provision of empirical scientific justifications

for our case. Aptly termed the Hiroshima Syndrome, we examine

two main scientifically untenable beliefs of this radiation paranoia

that (1) nuclear power is explosive and therefore any nuclearrelated facility has the possibility of a nuclear detonation, and (2)

nuclear power plant releases are the same as nuclear weapon

fallout (Corrice 2015a).

The first misinformation premise pertains to public

knowledge that both cases use highly reactive radioactive material,

leading to the fear that nuclear explosions can occur in any nuclear

facility. However, while the material used in the radioactive chain

reactions may be similar, concentrations are vastly different.

Uranium-235 used in weapons production are highly concentrated

to about 90%, allowing fissions to sustain a chain reaction, but

those in reactors are diluted to contain less than 5% (WNA 2014),

so fissions operate in conditions where a chain reaction is not

sustained; reactor fuels hence are technically too dilute to result in

any nuclear explosion, even in unexpected natural disasters.

Similarly, the explosion at Fukushima Dai-ichi Unit 3 was

arguably not a nuclear explosion but a steam explosion due to a

malfunctioned build-up of hydrogen gas (WNA 2015). Due to the

fundamental technical architecture of nuclear reactors, the public

fear that nuclear explosions like those at Hiroshima can occur in

nuclear plants is necessarily untrue.

11

Japan After 3.11

The second misinformation premise pertains to public

knowledge that radiation is released into the atmosphere in both

nuclear weapon explosion and nuclear reactor malfunction, leading

to the fear that the constituents of such releases are similar.

However, a nuclear explosion is dangerous because its detonation

releases the high amounts of gamma rays and neutrons that makes

the surrounding dust particles radioactive and causes what is

known as a fallout (Corrice 2015b), but due to a lack of

detonation, nuclear reactors mostly only release alpha and beta

particles which, while dangerous when ingested, only travel a few

meters and can be stopped by clothing (NRC 2014). Once again,

using scientific technical knowledge, we know that the fear that the

Fukushima disaster could cause widespread radiation as in

Hiroshima is necessarily unfounded.

Summary

The basis for fear can be traced back to Hiroshima, where

anti-nuclear and pacifist concerns have been equivocated, leading

to a misrepresented superimposition of beliefs from the aftermath

witnessed of nuclear weaponry onto a malfunction of peaceful

nuclear energy production. Such misinformed beliefs can be

attributed to a fundamental lack of public scientific information

about the differences in technical architecture and constitutive

radioactive elements between nuclear weapons and nuclear plants.

Having now established that radiation paranoia is prevalent

amongst the public and yet scientifically unfounded, we proceed to

argue that the urgent disaster recovery challenges at hand that is

currently claiming lives in Fukushima stems from this unnecessary

fear of radiation, rather than the radiation itself.

The Consequence of Fear:

Humanitarian Challenges in Fukushima

As a result of radiation paranoia being a human security

issue, disaster recovery challenges from such a security breach in

Fukushima comprise not so much of physical or biological health

concerns pertaining to radiation, but the psychological and

sociological well-being of survivors and refugees in humanitarian

communities. The governments physical evacuation and

containment measures may have kept people safe from the

physical effects of radiation but not from the psychological

12

Japan After 3.11

impacts (Brumfiel 2013: 290); in fact, evacuation may have in

turn led to more complex humanitarian consequences, not unlike

the hibakusha (disaster survivors) of Hiroshima. It will be argued

that such psychological and sociological consequences on

Fukushima victims have been exacerbated due to radiation

paranoia on the part of the government, the collective public and

the refugees themselves.

Consequences of the Governments Radiation Fear

As with the hibakusha who fled Hiroshima after its

destruction, the Fukushima evacuees too experienced severe shock

from losing their sense of home. Due to the alleged severity of

the Fukushima disaster and the prompt and large-scale government

evacuation response, hundreds of thousands of locals have left their

hometowns, with more than 100,000 refugees still remaining in

kasetsu (temporary housings) situated outside evacuated zones

(Fukuleaks 2014). These abrupt relocation measures have caused

transfer trauma (WNA 2015) due to the forced move of the

elderly from hospitals and homes, and have put immense

sociological stress on familial relationships due to space constraints

in the kasetsu that have resulted in families members being divided,

causing them to live separately (Maruyama 2015: 113). Moreover,

with the loss of their original community, it follows that there is

naturally a subsequent loss in the refugees own livelihood as well.

Refugees have been reported to be suffering from spiritual fatigue

brought on by having to reside in shelters (WNA 2015) because

they are unable to make concrete long-term plans for their future in

terms of employment or education due to the temporary nature of

these housings arrangements. Regardless of radioactive biohazard,

the very evacuation to kasetsu itself has resulted in a whole host of

sociological and psychological problems for refugees.

Consequences of the Publics Radiation Fear

For those from Fukushima who have not been evacuated officially

by the government but have chosen to relocate to other towns,

there have been cases of public discrimination. Similar to the

hibakusha who, treated like social pariahs (Jacobs 2014), were

declined jobs for fear of contamination or rejected by marriage

partners for fear of malformed children, the Fukushima refugees

face similar discrimination as well, with the children of evacuated

13

Japan After 3.11

families becoming victims of bullying at schools, cars with

Fukushima license plates scratched (Heath 2013: 71-73) and new

refugees being confronted by old locals to leave their towns (Japan

Times 2013). With these hindrances from assimilating into their

new environment, no friends, jobs or schooling, many have

developed acute social withdrawal symptoms (Ballas 2011). As a

result of the prevalent fear of radiation amongst the public in towns

that are safe but seeing an influx of refugees, public discrimination

has resulted in psychological anxieties amongst the victims.

Consequences of the Refugees Radiation Fear

Even individually, because of the invisible and imperceptible

nature of radiation, refugees suffer from perpetual uncertainty as to

whether or not they would eventually contract radiation sickness,

with every physical symptom such as fever or skin irritation

causing chronic worry, as experienced by the hibakusha after

escaping Hiroshima as well. The crux of this issue is not so much

whether empirical data shows radiation levels are sufficiently high

which contrariwise, actually is not, according to international

scientific experts (IAEA 201: 9; UNSCEAR 2013: 10; WHO 2013:

8) but their individual psychological belief, exacerbated by the

stringent hospital treatment procedures required (AFP 2011), that

makes them assume the radiation is lethal. This has resulted in the

rise in individual anxiety and stress-related disorders amongst

refugees, where, in a psychiatric survey conducted, adults showed

signs of extreme stress and mental trauma (Brumfiel 2013: 291),

resulting in many developing into depression and in some cases,

even suicide (CNN 2012). These are but instances of indirect

deaths that have already overtaken those killed in the earthquake

and tsunami, signalling a great urgency to tackle this disaster

recovery challenge and eliminate radiation paranoia.

Summary

At this point of writing, there have been no reports of

anybody dying from radiation due to the Fukushima incident.

However, being unable to return to their homes, scattered in

evacuations centres, facing discrimination and confrontations from

society, and constantly worrying over their own personal biological

health, a growing number of evacuees are ironically developing

mental health problems, with many dying from anxiety, from

14

Japan After 3.11

suicide or from simply losing the will to live (BBC 2014). Due to

this history of stigmatisation dating back to the atomic bombs

(Economist 2012) being perpetuated into what is treated as merely

another iteration of Hiroshima when the reality is that both are

vastly different, the human security issues in Fukushima have

become increasingly more complex, involving radiation paranoia

that has resulted in human security breaches that need to be

urgently tackled through disaster recovery in order to achieve

freedom from fear.

Preliminary Policy Proposition

Having explained that human security challenges ultimately

stem from radiation paranoia, the most logical and straightforward

way of ensuring human security by pursuing freedom from fear is

then to take action to remove the cause of radiation fear altogether.

This paper proposes a basic preliminary policy recommendation as

follows:

Policy 1

Eliminate the object of fear

Complete

and

sustained*

shutdown and decommissioning

of nuclear plants

(Anti-nuclear stance)

*As of 31 March 2015, the nuclear plant restart of Sendai Nuclear

Power Station, located in Satsumasendai, Kagoshima Prefecture

and owned by Kyushu Electric Power Company, has been

approved by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe as well as the governor of

Satsumasendai, and is already undergoing on-site inspections by

NRA (Japan Times 2015); if it is to be restarted according to plans,

it will then be the first nuclear power plant to do so since the 3.11

disaster and will set a precedent for future restarts across the

country.

Policy 1 Assessment

The proposed preliminary policy is the most direct solution

should we choose to pursue a strategy that aims to eliminate and

ultimately prevent the aforementioned human security issues from

occurring. Basically, if there are no more nuclear power plants,

15

Japan After 3.11

there can be no need to fear the consequences of a nuclear accident,

thereby achieving the human security of freedom from fear.

However, this most ideal and effective situation is only able to

theoretically work ceteris paribus, if we do not have other political

security challenges to consider apart from human security. This is

however not the case in this dynamic world of politics and

international relations, especially for Japans political situation at

present.

The chief difficulty in implementing Policy 1 is that its

inverse that is, restarting nuclear plants is a policy that is

urgently needed. While we acknowledge the importance of

ultimately achieving human security, we recognise that the pursuit

of human security is only possible when state security interests are

guaranteed; as has been laid out, state security is the guarantor of

human security, and human security our imperative pursuit. In the

pursuit of state security, it will be seen that the restart of nuclear

plants is in the interest of securing domestic political economic

stability and international energy independence for the state and

relevant energy stakeholders, especially pertinent in light of

economic issues and regional political tensions rising in relation to

Japan. The urgent case for pursuing state security, put in context of

Japan, will be justified in the following chapter.

Another issue of contention with Policy 1 is that while its

implementation may be able to liberate the people from radiation

paranoia and thereby eliminate the humanitarian security breaches,

since there will no longer be the possibility of nuclear accident

occurrences, this policy does not directly address the disaster

recovery challenges from the fact that the Fukushima disaster has

already caused human security breaches, with people currently

suffering from psychological issues of depression, stress, anxiety,

discrimination, social withdrawal and suicide. While the shutting

down of nuclear plants may be effective since it is easier to ensure

human security through early prevention than later intervention

(UNDP 1994: 22), it does nothing to mitigate the present human

security challenges currently faced by refugees. Hence, a revised

policy must be proposed to address these current challenges

persisting due to the breach; this will be discussed in the end of the

next chapter.

16

Japan After 3.11

III

State Security: Interests of the

Japanese Government

In light of the difficulties in implementing Policy 1

aforementioned, this chapter shall elaborate on the specific reasons

why Policy 1 is impossible when we consider Japans strategic

domestic and international interests at present. The main thrust for

this chapter is based on the argument that the state seeks to

guarantee state interests before it can proceed to manage human

security concerns. Opposed to the idealism of an anti-nuclear

policy, we shall approach the issue of state security through a

structural realist perspective, beginning internally with the

domestic political and economic structures regarding nuclear

power in Japan, leading externally on to Japans international

relations with various state actors for the sake of securing state

sovereignty and energy independence.

We shall argue that the interest of the Japanese government

with respect to nuclear power decisions is entrenched in what is

known as the nuclear village, which consists of both state and key

non-state actors, mutually influencing each others interests. The

immediate problem with so-called state interests then is that

matters are no longer clear-cut, since these powerful private actors

who are often pro-nuclear would be interested in keeping the

nuclear village and restarting nuclear plants. Yet, it would be

remiss to only accord responsibility to private actors; due to the

complex bureaucratic architecture of the nuclear village and the

inertia of incumbent interests, the Japanese government is simply

unwilling and unable to sustain a total shutdown and

decommissioning of the nuclear plants.

Having presented the domestic interests supporting the

nuclear village, we proceed to critically discuss the importance of

this village regarding Japans state security challenges; this will be

examined through Japans relations with US and China, and with

the Middle East. In order to maximise Japans defence capabilities

17

Japan After 3.11

to protect its sovereignty amidst rising regional tensions with China,

there is vested military interest with US to maintain the nuclear

village and to restart nuclear plants to secure possible nuclear

capabilities in Japan. For the sake of safeguarding Japans energy

independence, the nuclear plants must be restarted to diversify

from conflict-ridden Middle East, and the nuclear village provides

economic means to trade nuclear technology for stable fossil fuel

supply, justifying Abes proactive pacifism policy to secure

Japans own regional state security.

With these justifications for the nuclear village and nuclear

restarts, policy can no longer be based solely on human security

issues. We cannot eliminate the object of fear by shutting down

nuclear plants, since restarts have been shown to be important for

state security, which in turn guarantees human security. Hence, by

reconceptualising the freedom from fear strategy, then we shall

instead eliminate fear of the object, which actually proves to be

more comprehensive as it allows us to additionally address present

human security breaches of disaster recovery challenges as

mentioned. These two policy actions will thus constitute our final

policy proposal regarding nuclear restarts.

Domestic Political Economy:

The Inertia of the Nuclear Village

The nuclear village refers to an intersecting conglomerate of

various players within Japans nuclear industry, consisting of

governmental, political, industrial, academic and media

stakeholders. For the purposes of this paper, we shall focus on two

key citizens of the nuclear village: the nuclear power

administrators and the nuclear power industry leaders, or the state

and non-state actors respectively. However, if we are to be looking

at state security interests, why do we have to consider non-state

actors? In this case of Japanese electric companies, these private

actors, especially TEPCO, exert enormous influence in terms of

political, economic and technological leverage on regulatory

bodies to secure their own private interests. Nonetheless, the state

and its relevant regulatory bodies are still largely responsible for

the inertia of the nuclear village due to bureaucratic complexities

between actors, as well as post-Fukushima structural reforms

already planned, altogether lending weight to the incumbent

interest against emergent post-Fukushima anti-nuclear interest.

18

Japan After 3.11

Influence of Pro-Nuclear Industry Leaders

As the principal industry leader amongst the energy

companies, providing approximately one-third of all power in

Japan, TEPCO has consistently exerted a major influence on

national government policy decisions (Bricker 2014: 73). This

influence that TEPCO exerts on national energy policy, and by

extension, the nuclear plant restart decisions, can be identified

through political, economic and scientific leverages that TEPCO

possesses.

TEPCO is able to assert its private interests on policy

because of its political leverage, through a practice of amakudari

(literally, descent from heaven) which involves bureaucrats taking

positions in companies they formerly regulated, and industry

officials being represented on influential government advisory

panels (Colignon and Usui 2003). Former TEPCO executive vice

president Tokio Kano was elected to the Upper House of the Diet

through LDP backing, coinciding with a significant rise in

donations (Asahi 2011a), and former staffers from the central

bureaucracy such as METI, MLIT, MOFA and MOF have been

employed by TEPCO, including a former energy minister who

became TEPCOs vice president (Bricker 2014: 74). With this

revolving door mechanism firmly rooted in place, TEPCOs

involvement in Japanese politics and regulations is easily

facilitated and sustained.

Additionally, due to its economic leverage as one of the

largest private-sector energy firms worldwide, TEPCO asserts its

private interests through kickbacks like contributing large sums of

money to local governments in exchange for hosting nuclear power

plants. TEPCO contributed US$110m to build a soccer stadium in

Naraha, an aging town in Fukushima Prefecture which needed to

attract youths, in return for hosting Fukushima No.2 Nuclear Plant

(Asahi 2011b). Nonetheless, this financial contribution has

distinctly improved the community (Bricker 2014: 76) through

employment and by hosting national sporting events, alleviating its

socio-economic circumstances, undeniably in the interests of the

government as well, thus providing little incentive for state

intervention.

19

Japan After 3.11

As the non-state actor that is actually involved in the

technical generation of nuclear power, as opposed to state

administrators, TEPCO possesses technological and planning

capabilities far superior to those of government agencies such as

NISA or ANRE (Bricker 2014: 74-75), which provides the firm

significant leverage to direct government policies. By coming to

the table with watertight proposals according to its own interests

and by pointing out technical errors in other energy proposals by

regulatory bodies, TEPCO continues to exert a profound influence

on the direction of government policy.

Bureaucratic Complexities and Incumbent Interest

Yet, while it appears that the nuclear village is driven by the

private interests of large pro-nuclear energy companies, it is

fundamentally still built upon the complex bureaucratic

interactions involved in its inception and continuity. After the end

of WWII, nationally-controlled electric power was privatised into a

system of regional monopolisation, dominating all the processes

from power generation, transmission, distribution and sales

(Bricker 2014: 73). Until 3.11, this monopolised industry needed to

be strictly regulated by NISA, which oversees regulatory

compliance from within METI. Yet the irony was that this

regulatory body was an arm of METI, the government agency most

committed to expanding nuclear power (Dewit et al. 2012: 157).

As a result of this bureaucratic structure where government

regulators regulated in favour of the regulated (Kingston 2014: 41),

it was always possible for moral hazard to undermine professional

accountability indeed, in 2002, NISA finally publicly disclosed

that TEPCO had been falsifying data for many years to conceal

various problems (Bricker 2014: 69). Nonetheless, such almost

self-regulating mechanisms remain in place to continue ensuring

that the nuclear village survives.

In addition, by virtue that the entire nuclear village is wellorganised and sufficiently united in their policy vision (to promote

nuclear power), with trillions of yen worth of sales, assets and

investments at stake, there is a strong incumbent interest by all

actors, state and non-state alike, to defend the status quo and keep

this nuclear village alive, a powerful and important structure of

energy and policy-making in the worlds third largest economy.

The main strategic advantage of these stakeholders in this colossal

20

Japan After 3.11

structure is that it need only defend the status quo, because

significant change in any policy realm is always difficult. Even

after IAEAs report that the roles of both NISA and NSC

especially with regard to the nuclear safety guidelines should be

clearly identified (IAEA 2007), it was only after 3.11 happened

that reforms of regulatory bodies actually proceeded, finally taking

NISA and NSC away from METI control and housing it under

MOE as a more independent NRA. Moreover, with the Diet

effectively deadlocked between the LDP and DPJ with no sign of

clear and consistent leadership, from Kans anti-nuclear stance

right after 3.11 in 2011 shifting to Abes increasing support of

nuclear power at present, the political context remains fluid and

policymakers are occupied in policy debates rather than policy

itself. Amidst this situation, METIs strong support for nuclear

power and retaining control over national energy strategy is

therefore an invaluable stability that advocates for incumbent

interest, thereby allowing the nuclear village to persist, and sooner

or later, permitting nuclear restart once again.

Summary

The interest of the state in nuclear policy is fraught with the

political, economic and technological advantages that the private

energy companies, especially TEPCO, hold in the realm of

policymaking. Moreover, with bureaucratic structures in the

nuclear village involving complex, almost self-regulating

mechanisms, the strategic advantage of maintaining only its

incumbent interests, and the strong and stable policy vision it

carries amidst uncertain political discourse, it is clear that with its

enormous power to influence public discourse and politics

(Kingston 2012: 204), the nuclear village, desperate to survive,

will indeed live on.

International Security:

Interstate Relations and Japans Sovereignty

Having argued that the domestic community of electric

utilities and bureaucrats comprising the nuclear village have vested

interest in sustaining its existence by opposing shutdowns and by

extension, pushing for nuclear restarts, we proceed to recognise the

nuclear village goes beyond being only a domestic issue. By

looking at Japans strategic role on the regional and international

21

Japan After 3.11

level, we recognise, through the lens of structural realism, the

nuclear village provides the means for Japan to achieve its need to

both maximise capabilities and minimise constraints within the

structure of international relations in order to secure its sovereignty.

This will be analysed through case studies of Japans relations with

China and US, as well as with the Middle East.

Maximising Capabilities: China, US and Nuclear Weaponry

With tensions rising recently between China and Japan, due

to the ongoing Senkaku island disputes (MOFA 2014) which has

resulted in maritime security and sovereignty issues, in addition to

the already persistent nationalistic politics of apologies over WWII

war-crimes (MOFA 2006), it is especially at this crucial political

juncture where Japan needs to maximise its security capabilities to

ensure state survival. In order to utilise the various actors within

this regional political structure, Abe has proceeded by visiting all

ten ASEAN states to strengthen both diplomatic and economic ties

(Sekiyama 2014), securing multilateral networks to hedge against

Chinas rise. On a national level, his government has reinterpreted

Japans peace constitution to permit collective self-defence and

further his policy of proactive pacifism in order to justify future

objectives to take on further hedging measures against China.

However, while somewhat effective at engaging with Chinas

offensive expansionary claims on a diplomatic and economic basis,

these measures at best only serve as indirect soft deterrents against

Chinas increasingly hard military capabilities, such as its secondstrike capability while disallowing its nuclear programme to be

subject to international restrictions (Cabestan 2013), as well as land

reclamation for airstrip construction in the Spratly islands for

greater maritime and airspace assertion (Reuters 2015). By a

structural realist analysis of military might, the lack of defensive

manoeuvres on Japans foreign policies may prove insufficient.

However, the rise of China as a regional power both

economically and militarily is also disrupting the present power

configuration in the Asia-Pacific region firmly established by the

Japan-US security architecture. Thus, in accordance to its

rebalancing strategy into Asia, US has a security interest in

strengthening its bilateral alliance with Japan, to maintain its

military presence and counterbalance Chinas rise. According to

structural realist interpretation then, since ASEAN is not a security

22

Japan After 3.11

complex, Japans recourse would be to leverage on this US alliance

structure to allow nuclear weapons as a balancing possibility

against Chinas military threat. Indeed, Prime Minister Abe has

identified the benefits of retaining nuclear energy as a way of

keeping Japans nuclear weapons options open (Bacon and Sato

2014: 164), consistent with US geostrategic interest in securing its

military presence, after having pressured the Japanese cabinet for

no decision to be made for a phase-out zero option (Tokyo Shimbun

2012), since the existence of nuclear plants means the practical

possibility of producing an A-bomb within one year (Global

Security Newswire 2012). Hence, from a security perspective of

structural realism, US and Japan both benefit from Japanese

nuclear technology, and would therefore be disadvantaged in the

dynamic regional power relations if the nuclear village, and by

extension the possibility of nuclear weapons, was to be abandoned.

Minimising Constraints: Middle East, Conflict and Nuclear Energy

There is also strategic interest for Abe to retain nuclear

energy capacity in Japan when we look at its economic and

security relations with the Middle East. As a nation that is limited

in natural resources and thus heavily reliant on energy imports,

Japan is primarily dependent on the Middle East which provides at

least 80% of all its fossil fuel imports. After 3.11 and the shutdown

of all nuclear plants across Japan, this number has only increased;

with the comparatively inexpensive nuclear energy representing a

quarter of Japans energy supply out of the equation, this has

further deepened Japans energy and economic dependency in the

conflict-ridden Middle East, opening possibilities for likely

compromises on foreign policy (McCann 2012: 3). Hence, in order

to minimise Japans own structural constraints and circumvent

possible economic ramifications should the Middle East region

destabilise further, and possibly see Japans oil partners

compromise its willingness and ability to sustain trade, Japan has a

security interest in restarting nuclear plants. By alleviating current

energy supply strains and costs through a domestic baseload power

source, as well as to diversify away from this increasingly

destabilising region due to the ongoing irredentist conflicts,

towards other strategic actors such as Russia, Southeast Asia and

Africa for energy stability (EIA 2015), Japan puts itself in a better

position to secure its own energy independence.

23

Japan After 3.11

Moreover, with the ISIS murder of Kenji Goto, Abe has

leveraged on this security incident to further justify his proactive

pacifism by taking on a more proactive foreign policy stance to

enhance security and economic cooperation with the Middle East

(MOFA 2015). This functions as a pretext for exporting more

nuclear technologies to the region, a strategy that remains

consistent with Abes recent negotiations with Saudi Arabia and

UAE (Nikkei 2014), two of Japans major energy partners, as well

as other state actors in the region, in exchange for securing future

supply of fossil fuel for the sake of Japans energy stability. Hence,

there is a state interest not only in nuclear restarts but in the

persistence of the nuclear village as an economic tool to minimise

its own energy constraints through economic cooperation to secure

energy independence, as well as a diplomatic tool to minimise its

own military constraints by legitimising Abes own proactive

pacifism foreign policy to the international community, a

decisively strategic move that ultimately is drawn back to Japan

own concern with regional tensions regarding China, so as to

justify strengthening the established regional security alliance

structure with US and further enhance its military capabilities for

the sake of safeguarding Japans sovereignty.

Summary

Regarding the rise of China and the security threat it poses,

maintaining nuclear energy with respect to the Japan-US alliance

maximises Japans capabilities by keeping the option of nuclear

weapons open as a defensive manoeuvre to balance against China,

thereby safeguarding their key positions as stabilisers in dynamic

security framework within the Asia-Pacific region. In the case of

the Middle-East, restarting nuclear plants would then reduce

dependence on the conflict-ridden region, and in light of Kenji

Gotos murder, keeping the nuclear village minimises constraints

by allowing Abe to secure future supply of oil from its export

partners while further legitimising his proactive pacifism to

secure Japans regional state sovereignty.

24

Japan After 3.11

Final Revised Policy Proposition

Having argued at this point that the nuclear restarts and the

nuclear village are necessary for state security, this rules out the

preliminary proposal to keep nuclear plants shut down; Policy 1 is

therefore replaced by Policy 1, whereby the object of radiation

fear cannot be eliminated, and restarts must occur. However, since

the pursuit of human security is imperative, instead of seeking to

eliminate the object of fear, we shall then eliminate fear of the

object, through radiation literacy, psychiatric humanitarian

assistance and DDR management expertise. This final revised

policy proposition stands as follows:

Policy 1

Eliminate the object of fear

Complete and sustained*

shutdown and decommissioning

of nuclear plants

(Anti-nuclear stance)

Policy 1

Impossible to

eliminate the object of fear

Policy 2

Eliminate fear of the object

Prompt restart of nuclear plants

(a) Education of the public masses

regarding radiation literacy;

(b) Provision of psychiatric and

community assistance to

evacuees;

(c) Investment in DRR

management expertise in

accordance to SFDRR

Policy 1 Assessment

Policy 1 follows as the logical conclusion of the chapters

arguments against nuclear shutdowns and for nuclear power

generation to persist in Japan. However, while Policy 1 was

labelled as the anti-nuclear stance, it would be remiss to simply

label Policy 1 as the pro-nuclear stance. The fact of the matter is

that such nuclear discourse has often been separated discretely such

25

Japan After 3.11

that one category finds itself pit against the other, with little

possibility of negotiations or compromise. This false dichotomy

that ignores consolidated thought only serves to eschew how we

are to perceive the reality of present circumstances, and the most

we can make of it at this juncture. The fact of the matter is that

nuclear plants exist in Japan, and perhaps it is important to rely on

nuclear energy. However, we should not be pursuing nuclear

energy blindly without recognising its great underlying risks, such

as the safety myth it proliferated (Bricker 2014: 50-62) amongst

energy firms and the public, or its great financial costs involved,

like the large financial payouts to refugees (TEPCO 2015) which

resulted in its partial nationalisation, especially apparent when we

witness the ongoing aftermath of 3.11 disrupting every strata of

society. Just because we have ruled out the possibility of a total

shutdown and decommissioning of all nuclear plants does not mean

that we ought to abandon any decommissioning whatsoever.

Indeed, as Maruyama suggests, from the human security

perspective, the appropriate approach to nuclear energy would be

to () decommission the outdated reactors as soon as possible

(Maruyama 2015: 108). This is one of the many possible human

security policy options we can further explore that should be

developed in the context of debate about the desired future

Japanese energy mix (Bacon 2014), once we have first and

foremost acknowledge that a total and complete shutdown is

impossible at this juncture, which has been the main aim of this

paper. It is always important to recognise that engaging human

security issues in humanitarian contexts does not mean that we

must remove all possibilities of disaster; rather, when we are aware

that anything man-made or natural will always be associated with

risks, we learn that the importance lies not so much in a

preoccupation with a total avoidance of risks, but in accepting their

possibilities and thus work towards identifying, managing and

reducing such risks.

Policy 2 Assessment

Policy 2 keeps our focus back on the imperative of human

security. Having shifted our strategy to accommodate the existence

of nuclear plants, as well as recognising that human security

compromises have already occurred, it follows then that our policy

must take into consideration not only prevention of radiation

paranoia to achieve freedom from fear, but also intervention to

26

Japan After 3.11

render appropriate humanitarian assistance and reduction of future

vulnerabilities through disaster risk reduction (DRR) mechanisms.

(a)

Prevention: Education of the Public Masses regarding

Radiation Literacy

In order to accomplish the main aim of eliminating fear of

radiation, it is important to raise radiation literacy amongst the

public masses. By raising awareness to the public about the truths

of the dangers by pointing out prevalent myths of radiation,

especially in identifying key differences in technical processes and

extent of radiation between nuclear weaponry and nuclear plants,

we can then explain the differences in atmospheric releases

between weapon detonation and reactor malfunction respectively.

However, the difficulty now lies in the fact that official radiation

information dissemination is facilitated by state administrators, of

which the public has increasing distrust for due to their

aforementioned ties with private energy companies, no less due to

TEPCOs and the governments failure to behave in an open

manner and provide honest, accurate information about what was

happening (Bacon and Hobson 2014: 12) during the Fukushima

incident. Therefore, no matter how scientifically justified their data

may be, even by international scientific experts, with such existing

misgivings on the side of the public, even the most objective of

information will not be readily accepted. As Professor Balonov, a

former ICRP member and consultant to WHO and UNSCEAR,

proposes, only an open information policy on the level of the

effects [through] the media and the science community will create

the trust needed to heal () and prevent negative socio-economic

effects from unwarranted anxiety and fear (WNN 2013). The local

academics of the scientific community, being visibly more

disinterested than the government, therefore play an integral role in

providing objective data for the public. In particular, according to

Professor Tanigaki whose KURAMA radiation device has been

placed into public transport around Fukushima city, with live data

being broadcast publicly in the city centre, the primary objective of

government policy is then only to minimally support the scientific

community with relevant administration and logistics, as the

scientists themselves move forward to provide transparent,

objective, accessible, comprehensible and sustained data to gain

the confidence of the public, and in so doing, fix the gap between

27

Japan After 3.11

truth and public perception in order to dispel the myths of

radiation (Tanigaki 2014: Appendix I).

(b)

Mitigation: Provision of Psychiatric and Community

Assistance to Evacuees

The immediate challenge of disaster recovery is the

psychological and sociological issues that have arisen amongst the

evacuees due to radiation paranoia; the question now turns to how

we ought to go about providing such assistance to refugees. With

the rising cases of anxiety disorders, depression and suicide,

alongside the cultural fact that Japanese societys values

emphasising conformity may also be a deteriorating factor for

stigma against mental illness, which deviates from the norm

(Taplin and Lawman 2012: 129), the very act of diagnosing

individuals as mentally ill poses difficulties, on top of the fact that

mental health is not a priority for this rural, conservative region

of Fukushima (Brumfiel 2013: 291). Hence, the challenge is to

provide psychiatric help without being categorically psychiatric

in order to gain trust. This is where the role of volunteer

community centres comes into play. According to Yui Hamada of

Nozomi Center (Hamada 2014: Appendix II), the role of running a

community centre was not only to serve as a safe place for children

whose parents both have to work since the disaster, but as one of

the places they will run to when they feel sad or lonely or scared

because the centre has earned the trust of the community. With

time, the rest of the local community had become encouraged and

slowly began to voluntarily contribute to the Centers community

projects, such as providing foodstuff and rendering humanitarian

support by visiting and cooking for kasetsu refugees. This is a

prime example of how strategies of community development and

involvement contribute to alleviating the psychological and

sociological challenges, where the aim of the government would be

to encourage and support through providing the financial means for

these humanitarian groups to sustain a long-term presence in the

communities.

(c)

Reduction: Investment in DRR Management Expertise in

Accordance to SFDRR

Out of all these three policy strategies, it is here in risk

reduction management where the role of the governments

28

Japan After 3.11

policymaking bodies is most integral. Due to the revolving door

and self-regulating mechanisms in place between the state and

TEPCO within the nuclear village, alongside METIs agenda to

promote nuclear power to the bureaucracy and the public, it was

inevitable that a safety myth, instead of a safety culture, was

promulgated. This did not reflect well on the governments part

even after 3.11 when the Cabinet reported, with respect to the

Hyogo Framework for Actions (HFA) priority for action 5:

strengthen disaster preparedness for effective response at all levels

(UNISDR 2005), that Comprehensive achievement with sustained

commitment and capacities at all level (Cabinet Office 2011: 20),

perhaps too positive a self-appraisal when the relentless cascade

about fundamental errors, lax enforcement of safety guidelines,

shady practices and negligence began unfolding soon after in

Japanese media reports (Kingston 2014: 40). It was not so much

the problem of the Hyogo Framework, but the governments

attitude in merely putting the legal and institutional framework in

place without worst-case scenario conceptualisation. With the

newly conceived post-2015 Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk

Reduction (SFDRR) underway, of which priorities for action 3:

investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience, and 4:

enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response, and to

Build Back Better in recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction

(UNISDR 2015), pertains especially to 3.11, one can only hope

that the government and relevant stakeholders learn from this

severe lesson and finally take a serious, honest and committed

stand by adhering to these safety priorities.

29

Japan After 3.11

IV

Conclusion

This paper has sought to argue, in a negative sense, against

the anti-nuclear policy of completely shutting down and

decommissioning all nuclear plants in Japan. This is fundamentally

impossible because of domestic and international state security

interests which require the inverse restarting nuclear plants.

Inasmuch as we ought to pursue freedom from fear in order to

eradicate radiation paranoia that finds itself enmeshed with pacifist

movements and unscientific misinformation originating historically

from Hiroshima, we cannot forget that the sovereignty of Japan

remains top priority, especially against the backdrop of a rising

China, whereby Japans military alliance with US and economic

trade relations with Middle East requires the domestic structure of

the nuclear village to persist in order to guarantee Japans state and

energy security. Yet, as we proceed to restart nuclear plants, it does

not mean that human security fades into irrelevance; always the

imperative, we must complementarily pursue a comprehensive and

prompt freedom from fear strategy alongside nuclear restarts to

meet the present exigent needs, through having the state provide

background support to the scientific community as they provide

radiation literacy to the public, financially assist humanitarian

organisations in their community involvement projects as they

work to meet the ongoing psychiatric and sociological disaster

recovery challenges of depression and discrimination, and invest

more in risk communication and risk reduction expertise as we

move on from the harsh lessons learnt from 3.11 and proceed to

work towards a post-2015 SFDRR Japan.

Acknowledging Limitations

This much is easy to say from an academic research

perspective. What remains out of the scope of this paper are the

detailed outlines of Japans future nuclear policy, that is, in a

positive sense, to what realistic extent nuclear restarts should occur.

What should the rate of restarting plants be? What is the time

frame we are looking at for restarts? Should we seek to restart all

30

Japan After 3.11

plants eventually, or place a limit, enough to provide a baseload

power minimum? What would constitute a nationally sufficient

baseload power minimum for a resource-scarce country as Japan?

Should we be considering the construction of even more nuclear

plants on top of existing ones in the future? These are extremely

important questions that policymakers have to come together to

address even as plans to restart the first nuclear plant may be

commencing as we speak. Yet, even as the newly-reshuffled

agencies come to the policymaking table with mature, experienced

pro-nuclear players in the nuclear village currently enjoying the

backing of pro-nuclear Abe, decisions to limiting nuclear plants

restarts from a human security perspective will definitely meet

many more bureaucratic challenges in this political complex. As

long as legislation does not discreetly revisit and lay out the

specific obligations of parties, the current safety regulatory

governance in which the locus of responsibility remains ambiguous

between state and private firms will continue to foster public

distrust of the bureaucracy. As Japan moves forward with nuclear

power, it is the states responsibility to provide a conducive

environment for ordinary citizens to have a sufficient perspective

to access critically the powerful bonds that exist among the

political and industrial communities comprising the nuclear village

(Bricker 2014: 61).

Future Recommendations

This paper has focused on the short term considerations of

Japan with respect to its immediate domestic and international

issues surrounding nuclear restarts. Looking ahead long term, on an

energy front, as Abe already begins diversifying energy partners

worldwide, the state should move from the 3.11 disaster and start

to seriously consider investments in other energy sources such as

renewables, a strategy strongly pushed by Softbank CEO Son

Masayoshi, the richest man in Japan, that has since expanded

policy momentum and maintained strong public support

nationwide (Dewit et al. 2015: 166-69). On a humanitarian front,

the time scale remains smaller but no less significant. Articulating

the precise sentiments of SFDRRs Build Back Better, Minako

Takahashi from Fukushima city says that she wants it to be a place

of hope tourism and show the foreign delegates who will come

for the 2020 Olympics how they have recovered and progressed

since the disaster (Takahashi 2014: Appendix III). The most

31

Japan After 3.11

pressing need for the government within these coming years then is

to steadily proceed with the expansion and reconstruction of urban

areas to provide permanent residences so that refugees can once

again be integrated into society. To this end, it is up to us

researchers specialising in Fukushima now to strategise how best to

sustain our research efforts by monitoring, supporting and raising

awareness of the humanitarian recovery, for refugees and the

public, governments and firms, as well as domestic and

international communities, all in the hope of a better age for Japan.

32

Japan After 3.11

Appendix

APPENDIX I

Excerpt from Research Presentation with TANIGAKI, Minoru

Assistant Professor, Kyoto Reactor Research Institute, Osaka

Efforts on decontamination are already underway, such as at roads

or houses in Fukushima. So what I should do is to show that efforts

are producing results. Thats why I am extending KURAMA-II

throughout the prefecture, to update daily, plot the data to show a

decreasing trend that radiation is dropping. This is what the citizens

should see that efforts are effective, and decreasing results are

maintained and this is what I would like to show them with our

system. As a result, our KURAMA-II system is well-received and

people are more trusting of our results than the government

monitoring posts, although they are not defective at all.

The KURAMA-II has been accepted because of its long continuous

activities in Fukushima. If we start a discussion on radiation, we

should rely on the results from KURAMA and its activities. We

want the people to have confidence in our activity, to trust in our

data that produces results, and we want to continue increasing the

number of monitoring devices and make it more comprehensive to

cover a wider area, so that the results can be communicated to the

public in a more transparent manner.

That is what I have told the people at Harvard University, at a

conference with the audience of specialists in risk communication.

It is important to fix the gap between truth and public perception

using KURAMA, if we wish to dispel the myths of radiation. ()

If we can show the results to the people properly, then they can

have the confidence to continue living there. If it is publicly

accessible, then it would be great, for that is how policies should

work, to tap on the scientific specialised expertise of the industry,

and to be able to disseminate such information in a manner

understandable for the public.

33

Japan After 3.11

APPENDIX II

Excerpt from Interview with HAMADA, Yui

Humanitarian worker, Nozomi Centre, Yamamoto Town

Q:

Can you tell us more about the situation in the community

when you first came here, and how the needs have changed?

Especially after the disaster, both parents had to work, so families

really appreciated a place they could send their kids, knowing that

they are safe and well taken care of. That need increased and we

are very thankful that the community trusts us and allows us to

have their kids here. The needs turned into more of emotional care

for traumatic experiences, because some kids will start shaking and

panicking once they hear the words tsunami or jishin

(earthquake), and they needed someone to be there when they had

those moments. Im glad and thankful that this place became one

of the places they will run to when they feel sad or lonely or scared.

Recently in the past months, people in the community have been

saying, I want to help you guys at Nozomi Centre, such as

cooking for people at the temporary housings, because the people

who had stayed here and then had their houses fixed, ready for

moving in right away, felt like they wanted to do something to help

the community in return. People wanted to contribute, and that was

a great step. I was also thrilled when grandmas and grandpas in the

area were telling us that hearing the kids voices and watching

them play around have encouraged them, so they brought food and

snacks to feed the kids and in all this I see the community is being

rebuilt, slowly but surely, in the love of Christ. Needs have

changed, but the fact that we have had the chance to be here in

Yamamoto for a while has helped our relationship and allowed us

to trust each other.

34

Japan After 3.11

APPENDIX III

Excerpt from interview with TAKAHASHI, Minako

Hotel owner, Matsushimaya Ryokan, Fukushima City

Q:

What is your hope for Fukushimas future?

Some say they want to make Fukushima become the spot of dark

tourism like Auschwitz, but we want to make Fukushima the spot

of hope tourism. We want to show how Fukushima, which has

suffered from compound disasters, is recovering and changing. We

want make the recovery so significant that our children can be

proud of the fact that they are born and grow up here. We go to see

government officials from Fukushima once every few months.

Moreover, in 2020, many foreign officials will come to Japan and

travel around as visiting delegations as part of the Olympics

tradition. When it happens, I want to show them how Fukushima

has changed and progressed dramatically.

Full original audio tapes, transcriptions and translations are

available upon request.

35

Japan After 3.11

Bibliography

AFP. Japan's nuclear evacuees shunned over health fears, (13

April 2011) Retrieved: 1 April 2015.

Asahi Shinbun. TEPCO orchestrated 'personal' donations to LDP,

(8 October 2011) Retrieved: 1 April 2015.

Asahi Shinbun. TEPCO quietly paid 40 billion yen to areas near

nuclear plants, (15 September 2011) Retrieved: 1 April 2015.

Ballas, P. Japan: Denial of Hikikomori Could Hinder Relief

Efforts, Psychiatric Times. (12 May 2011) Retrieved: 1 April

2015.

Bacon, P. The politics of human security in Japan in Bacon, P.

and Hobson, C. (eds.), Human Security and Japans Triple

Disaster. (Routledge, 2014), pp.22-38

Bacon, P. and Sato, M. What role for nuclear power in Japan after

Fukushima? A human security perspective in Bacon, P. and

Hobson, C. (eds.), Human Security and Japans Triple Disaster.

(Routledge, 2014), pp.160-179

Bacon, P. and Hobson, C. Human Security Comes Home in

Bacon, P. and Hobson, C. (eds.), Human Security and Japans

Triple Disaster. (Routledge, 2014), pp.1-21

BBC. Fukushima: Is fear of radiation the real killer?, (11 March

2014) Retrieved: 1 April 2015.

Bricker, K. (eds.) The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station

Disaster: Investigating the Myth and Reality. (Routledge, 2014).

Brumfiel, G. Fukushima: Fallout of fear. Nature Vol 493, pp.290293 (Macmillan Publishers, 17 January 2013).

Cabestan, Jean-Pierre. The Chinese nuclear arsenal and its

second-strike capability The Non-Proliferation Monthly, Issue 77

(CESIM, March 2013).

36

Japan After 3.11

Cabinet Office. Japan: National Progress Report on

Implementation of the Hyogo Framework for Action (2009-2011).

(Tokyo: Government of Japan International Office for Disaster

Management, 25 April 2011).

CNN. Husband of Fukushima suicide victim demands justice,

(Updated 21 June 2012) Retrieved: 1 April 2015.

Colignon, R. and Usui, C. Amakudari: The Hidden Fabric of

Japans Economy. (Cornell University Press, 2003).

Commission on Human Security. Human Security Now (New York:

Commission on Human Security, May 2003).

Corrice, L. Confusion about Fallout in The Hiroshima Syndrome.

Retrieved: 1 April 2015.

Corrice, L. What is The Hiroshima Syndrome? in The Hiroshima

Syndrome. Retrieved: 1 April 2015.

Dewit, A., Tetsunari, I., and Masaru, K. Fukushima and the

Political Economy of Power Policy in Japan in Kingston, Jeff (ed.),

Natural Disaster and Nuclear Crisis in Japan. (Nissan Institute:

Routledge, 2012), pp.156-171

Energy Information Administration. Japan, Analysis. (Updated 30

January 2015) Retrieved: 1 April 2015.

Eisenhower, D. D. Atoms for Peace, Address before the General

Assembly of the United Nations on Peaceful Uses of the Atomic

Energy, New York, New York December 8, 1953. (Abilene, KS:

The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, 8 December

1953).