Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Uniformity Articulation Trumpet and Violin

Hochgeladen von

Emilio Bernardo-CiddioCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Uniformity Articulation Trumpet and Violin

Hochgeladen von

Emilio Bernardo-CiddioCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Ohio Music Education Association

Perceived Articulation Uniformity between Trumpet and Violin Performances

Author(s): Shelly C. Cooper and Donald L. Hamann

Source: Contributions to Music Education, Vol. 37, No. 2 (2010), pp. 29-44

Published by: Ohio Music Education Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24127225

Accessed: 11-10-2016 15:19 UTC

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted

digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about

JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

http://about.jstor.org/terms

Ohio Music Education Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Contributions to Music Education

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Contributions to Music Education Vol.37, No. 2, pp. 29-44.

SHELLY C. COOPER AND DONALD L. HAMANN

University of Arizona

Perceived Articulation

Uniformity between Trumpet

and Violin Performances

Directors strive for a unified sound throughout their wind and orchestra ensembles. Artic

ulation affects sound uniformity among winds and strings. This baseline study examined

whether a trumpet player could better match a violin player's articulation, as perceived by

participants listening to a recording of two performances, when: (a) performing the musi

cal example with identical symbol indications as the violinist or (b) directed to listen to the

violinist's musical performance and then match the articulation. For dtach, spiccato, lour,

and to some extent the slur and martel the trumpeter's modified syllable had a marked

effect on the participants' choice of the best match. Consistent articulations among and

between ensemble sections enhance sound uniformity. However, the musical score may

not be the final conveyance needed to achieve uniformity. Individuals need to be aware of

the musical score s limitations in terms of articulation uniformity and have the knowledge

to address this issue.

A 11 directors strive for a unified sound throughout their ensemble, yet this goal may

xVprove even more problematic and elusive for symphonic orchestra directors. The

unique setting of addressing the diverse needs and tone production of both strings and

winds compounds the factors that may contribute to an ensemble lacking a unified

or blended sound. Hamann & Gillespie (2009) posit addressing articulation as ..

one of the more important concepts in string, brass, and woodwind teaching ..." (p.

153). This may be consequential as, in studies by Gillespie and Hamann (1998) and

Hamann, Gillespie, and Bergonzi (2002), one third of all orchestra directors did not

indicate a bowed string instrument as their major instrument.

29

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Contributions to Music Education

Unity of sound within an ensemble is dependent upon the nuances of sound

production for the various instruments involved. Hamann Sc Gillespie (2009) identify

three sound production factors associated with bowing: bow speed, weight (pressure),

and contact point (sounding point) of bow on the string (p. 64). Additionally, they

note these variables as interdependent upon each other, ". . .an entire palette of

sounds can be produced through changing the correlation between the three

sound production variables" (p. 65). Tone production for wind instruments also

involves three components: tongue, breath, and embouchure.

Brass and woodwind players execute articulation "... by the stopping and

starting of the airstream or flow by the tongue" (Hamann & Gillespie, 2009,

p. 154). Additionally, tongue placement and vowel syllable employed affects

articulation; the tongue cannot be considered a separate pedagogical entity for

brass players. Mueller (1967) correlated the tongue muscle to the brass instrument

as the parallel of the bow to the string instrument as a determination of initial tone

production whether "pointed or smooth" (p. 11). Snell (2001) defines articulation

as "the controlled release of the airstream" (p. 58) and is supported by Phillips

(1992) and Bachelder & Norman (2002).

Disagreement exists among string pedagogues as to the order in which to present

bowing articulations. Authors of string articles address the importance of establishing

a quality tone (Allen, 2003; Dillon, 2008) yet hold divergent views regarding bowing

sequence. For example, Rolland (1974) promotes dtach as the fundamental stroke

while Galamian (1985) endorses martel as the basic bow stroke.

Disagreement exists among wind pedagogues as to the optimal syllable usage

for particular articulations. Articulation involves duration control and ". .. consists

of momentary interruptions or manipulation of the air stream as it passes through

the lips and into the instrument" (Hunt, 1989, p. 38). Colwell and Goolsby (1992)

in their "Rehearsal Techniques" chapterfocus mainly on the attack and release

functions rather than specific articulations, but do address basic tongue placements

and syllables utilized (e.g., "doo," "tuh," etc.) for each wind instrument. They identify

style as "dependent on the interpretation of rhythm and the articulation of rhythm"

(p. 117) and also recognize articulation as a more complex involvement than mere

tonguing and slurring. "Articulation is the joining of notes together, and the ending

of the notes is as important as the beginning" (Colwell & Goolsby, 1992, p. 170).

Sullivan (2006) examined the effects of a multi-syllabic articulation approach

with high school woodwind students (N= 66) to determine articulation accuracy.

Results indicated that "multi-syllabic articulation" had a significant effect the

student's improvement of articulation accuracy in rehearsed and sight-read music.

Sullivan posits the students who utilized multi-syllabic articulation may have been

30

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Shelly C Cooper and Donald L. Hamann

assisted by the vocalizing of the syllables as . the syllables may have served as a

mnemonic device in helping those students remember the physiological response

better than subjects using the mono-syllabic approach" (p. 67). Whitener (1990)

also noted that "mental imagery" is an important component of sound concept

and interpretation for brass players. "By having a clearly realized image of the

sound one is trying to create present in the mind, the physical aspects of tone

production are guided to reproduce that sound" (p. 117).

When assisting string and percussion players, teachers and conductors are able

to identify overt behaviors (e.g., finger shape, bow hold, bow position, bow speed,

to some extent bow pressure, and so forth) affecting sound production, whereas

brass and woodwind playerswith their tonguing and embouchure not as readily

observablecan prove more problematic. Most wind instructors advocate the use

of various syllables to achieve hard or soft attacks. Yet, Hunt (1989) posits using

the same syllable for every student as "highly improbable" as "... all people do not

articulate the same consonant with the tongue in the same place" (Hunt, 1989, p.

38). Additionally, ".. . similar markings can result in different articulations .. ."

dependent upon the brass and woodwind players' expertise and performance level

(Hamann & Gillespie, 2009, p. 153).

Directors typically provide relevant performance-practice information during

rehearsals. Goolsby (1997) found that band directors spend a large proportion of

verbal instruction time addressing articulation errors and issues. Directors need

to extend beyond the typical verbiage of "play the note shorter" or "play the note

longer" when assisting students in their understanding of score interpretations

and suggested articulations. Schnoor (2002) encourages conductors to share their

thinking process in determining score interpretations with the ensemble members.

"Directors may experiment with different articulations to provide students with

tangible examples of style as it relates to musical expression" (p. 4). Schnoor

identified that these verbal exchanges ". . . stimulate students to explore stylistic

implications [which includes articulation] and listen with discernment" (p. 4).

How can a director create a"unified sound" across an orchestra ensemble? Meyer

(1956) uses "deviation in performance and tonal organization" to address a

performer's score actualization and stresses his readers not to consider performers

as "musical automatons" (p. 199). Meyer also identifies the score as providing "...

more or less specific indications as to the composer's intention, but it depends on

the performer to intensify or integrate these structural cues into a form that can be

communicated to the listener" (as cited in Kopiez, 2002, p. 529). The challenge,

therefore, is to create a process model that assists the ensemble members during

their integration of these structural cues to create a unified sound.

31

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Contributions to Music Education

Aural perception, as it relates to differences in conceptual and physical

interpretation and performance of the various articulations, remains a factor to

consider when generating "sound unity" among ensemble members. "We assume

that musical performance contains numerous so-called acoustical cues, such as

timbre, tempo, and articulation, which help to facilitate the communication of

the performers intentions" (Kopiez, 2002, p. 529). Schnoor (2002) notes: "The

literature suggests (Reimer, 1989,p. 93; Leonhard cHouse, 1972,p. 285; Swanwick,

1979, p. 38) that conductors should focus on . . . meaningful differentiations

when students are presented with differing expressive interpretations of the same

musical material..." (p. 7).

Hewitt (2001) noted that an individual's "aural conception" of sound "... can

be generated either internally (via audiation) or externally from a live or recorded

performance" (p. 309). Bundy (1987) and Kepner (1986) identify external models

as superior to internal models in reliability and accuracy. Similarly, Hewitt (2001)

identified that students listening to an aural model "... increased their performance

scores more than those who did not in the subareas of tone, technique/articulation,

rhythmic accuracy, tempo, interpretation, and overall performance" (p. 318). Other

research supports aural models positively affecting music performance (Dickey,

1991,1992; Puopolo, 1971; Rosenthal, 1984; Zrcher, 1975).

Although individual disciplines discuss sound production and articulation

issues, what is not occurring are the discussions that address matching articulations

across all instruments to create "sound unity" within an ensemble. Research

questions guiding this baseline study included:

1. Does the written music symbole.g., an accent or a dot above a

noteconvey the same articulation interpretation message to a brass

player as to a string player?

2. Will a brass player performing a musical selection, given the musical

symbols provided on the page, use one type of musical articulation

syllable when playing the example, change that articulation syllable

when asked to listen to and then match a bowed string performance?

3. Will musical selections played on a bowed stringed instrument us

ing various bow strokessuch as dtach, staccato, slurred staccato,

slur, martel, spiccato, lour, and collbe "matched best" when

a brass player performs the same selections given only the printed

musical page information or when the brass player hears the per

formance on the bowed stringed instrument and then attempts to

match the articulation?

32

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Shelly C Cooper and Donald L. Hamann

The purpose of this study was to determine whether a trumpet player could

better match the articulation of a violin player, as perceived by participants

listening to a recording of two performances, under the following two conditions:

(a) when performing the same musical example with the same musical symbol

indications as the violinist or (b) when directed to listen to the violin performance

of the musical example and then match the articulation.

Methodology

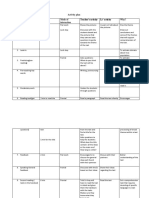

Eight musical examples were composed for violin and trumpet, and each

musical example employed various musical markings and tempo indications. The

trumpet examples were identical to the violin examples, same tempi, musical

symbols, and so forth, with the following exceptions: the trumpet examples were

transposed to sound in concert key and the violin example indicated the type of

bowing stroke that was to be utilized when performing (figure 1).

The eight bowing strokes used for this study were: dtach, staccato, slurred

staccato, slur, martel, spiccato, lour, and coll. See Table 1 for Klotman's (1996)

definition of these basic bowing terms. Using the original music composed

specifically for this study, a professional violinistwith 15+ years of experience

performing in professional-level orchestrasrecorded the eight selections. After

being presented with an A=440 hz, instructed to tune, and provided the indicated

tempo on a metronome, the violinist was directed to perform each of the eight

musical selections and apply the appropriate bow stroke as indicated on each of

the eight examples. The violinist was not provided any suggestions as to bowing

definitions or execution strategies.

A professional trumpet player, with 20+ years of experience performing

in professional-level orchestras, was provided the same selections (transposed

to sound in concert key). The trumpet version contained identical articulation

markings within the examples but without the bowing marking indicated. The

trumpet player, after being given an A=440 hz, instructed to tune, and provided

the indicated tempo on a metronome, was directed to play the first of the eight

examples at the correct tempo with an appropriate articulation given the indications

in the musical line. Following this initial recording, the trumpet player listened

to the violin recording and was then requested to play the example again with the

goal being to "best match the articulation of the violin performance. The trumpet

player was asked to indicate the articulation syllable used to perform each selection

using his own terminology. This process was repeated for all eight examples with

all tracks recorded in a professional studio and burned to a Memorex CD.

33

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Contributions to Music Education

Trumpet Excerpts

^ ^ Trumpet Excerpts

No. 1

Moderato J =92

Moderate

-92

i M 4, I . . mi I IT

No.

No.

4 4

Andante

Andante

J = 6()I = 60

No.

No.

5 5

Moderate

Mtxlerato

J -63 J = 63

No

No

6 6

Moderato

Moderate J

= 144

= 144

No. 7 ,

Andante

Andante J

J=

= 112

112

3KH

||

i===egg \u f f I

Figure 1: Trumpet Excerpts

The order of presentation of the violin and trump

on the original CD were then shifted to incorporate r

burned to another Memorex CD. The violin excerpt

followed by the two trumpet variations and then a repea

34

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Shelly C. Cooper and Donald L. Hamann

(Violin, Trumpet 1,Trumpet 2, Violin). The order of trumpet variations (Trumpet

1, Trumpet 2) was randomized for the CD using a Random Number Table.

Participants were then asked to assess the trumpet performances by indicating

which performance they felt best matched the violin performance.

Table 1

Klotman's

Klotmaris (1996) definition of bask

basic bowing

bowing terms

terms

Dtach "Literally,

"Literally,

the term

the term

merely

merely

means

means detached

detached

notes

notes

that are

that

notare

slurred.

notInslurred. In

practice

practiceititisisthe

the

smooth

smooth

change

change

from

from

one bow

one stroke

bow stroke

to another.

to another.

Often itOften

is

it is

misrepresented

misrepresented

as as

meaning

meaning

strokes

strokes

withwith

a space

a space

between

between

notes." notes."

(p. 162) (p. 162)

Staccato "The staccato

"The staccato

note note

is aisshort,

a short,stopped

stopped note

note

played

played

with the

with

bowthe

remaining

bow remaining

on

on the

thestring.

string.

There

There

areare

many

many

types

types

of staccato;

of staccato;

the style

theof

style

music

ofdeter

music deter

mines

minesthe

thetype

type

toto

be be

played."

played."

(p. 164)

(p. 164)

Slurred Staccato See definition above

Slur "Slurred notes"Slurred

are those

notes

thatare

continue

those that

in the

continue

same direction

in the same

ordirection

follow inor follow in

sequent

sequent without

without aa bow

bow change.

change. The

Thecharacter

characterof

ofslurred

slurrednotes

notesmay

mayvary.

vary.

ItIt

may besmooth,

smooth,staccato,

staccato,ororeven

evenspiccato."

spiccato."

166)

maybe

(p.(p.

166)

Martel "The martel

"The

is a martele

staccato is

stroke

a staccato

that stroke

is referred

that to

is referred

as a 'hammered'

to as a stroke.

'hammered' stroke.

Each stroke

stroke must

must be

be prepared

preparedfor

forby

bypressure

pressurebefore

beforeplaying

playing

and

and

followed

followed

byby

an immediate

immediate release

release of

of pressure.

pressure.At

Atthe

thesame

sametime

timethe

thebow

bow

is is

drawn

drawn

quickly.

quickly.

The next

next stroke

stroke follows

follows the

thesame

sameprocedurepressing,

procedurepressing,releasing,

releasing,

and

and

at at

the

the

same time

time moving

moving the

the bow

bowquickly.

quickly.As

Asininstaccato,

staccato,the

thebow

bowremains

remains

inin

con

con

tact with

with the

the string

string at

at all

alltimes.

times.However,

However,martel

marteleisismore

moreaccented

accented

and

and

it it

is is

marked

marked with

with aa wedge

wedge (V)."

(V)."(p.

(p.167)

167)

"The spiccato

is an off-the-string

stroke.

It sometimes

is sometimesreferred

referred to

Spiccato "The spiccato

is an off-the-string

bow bow

stroke.

It is

to asas

'bouncing

'bouncing bow.'

bow.' However,

However, one

onemust

mustcareful

carefulnot

nottotoassume

assumethat

that

the

the

bow

bow

is is

bounced

bounced like

like aa ball.

ball. Actually,

Actually,the

thespiccato

spiccatobow

bowmoves

movesinina ahorizontal

horizontal

direc

direc

tion like

like aa dtach

detache bow

bow except

exceptthat

thatthere

thereisisa alife

lifebefore

beforeand

and

after

after

the

the

stroke,

stroke,

creating

creating the

the bouncing

bouncing effect."

effect."(p.

(p.168)

168)

Lour "The lour"The

or portato

loure or style

portatoisstyle

a semi-staccato

is a semi-staccato

type

type

of of

bowing

bowingthat

that is

is

smoothly

smoothly separated,

separated, or

or 'pulsed.'

'pulsed.'ItItisisused

usedtotoenunciate

enunciatecertain

certain

notes

notes

without

without

pausing

pausing between

between them.

them. To

To accomplish

accomplishthis

thistype

typeofofbowing,

bowing,a a

slight

slight

pressure

pressure

is placed

placed on

on the

the notes

notes ..(p.

..(p. 171)

171)

Co "This stroke

"This

begins

stroke

with

begins

thewith

bowthe

being

bow being

placed

placed

on the

on the

string

string

similar

similar to

to an

an V

V

bow spiccato.

spiccato. At

At the

the moment

momentof

ofcontact,

contact,the

thestring

stringisispinched

pinched

lightly

lightly

but

but

with aa sharp

sharp attack.

attack. As

As soon

soonas

asthe

thenote

noteisissounded,

sounded,the

thebow

bow

is is

immediately

immediately

lifted

lifted off

off the

the string

string in

in preparation

preparationfor

forthe

thenext

nextstroke."

stroke."(p.(p.

176)

176)

35

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

rsDutions to music education

Participants for the study were students (N = 111) from two unive

in the southwest and one in the northeast portion of the United States

completed the Articulation Assessment Inventory (AAI), which included

information regarding education, major instrument, years of private

major instrument, and years of performance experience on the major i

Participants included 20 bowed string players and 91 non-bow

players (winds n = 53, percussion n = 5, voice n = 26, piano n = 7)

94 undergraduate and 17 graduate participants in the study with

breakdown by major: BME 76, BM 18, MME 2, MM 5, Ph.D 2,

Years of private study varied from a minimum of 1 year to a maximum

The mean years of private study was 7.5 with a standard deviation of

The median years of private study was 7 years and the mode was 5 ye

study. Fourteen participants reported having 5 years of private study

Years of performance ensemble experience varied from a minimum of

to a maximum of 28 years. The mean years of performance ensemble

was 10.65 years with a standard deviation of 4.91 years. The me

performance ensemble experience was 10 years and the mode was

performance ensemble study. Twenty-three participants reported hav

of performance ensemble experience, the mode.

Students listened to the eight musical examplesof which ea

contained four performances (Violin, Trumpet 1, Trumpet 2, Vio

Trumpet 2, Trumpet 1, Violin). Based on these 8-measure melodies

were asked to choose the trumpet performance that "'best matchecT the

of the violin performance.

Results

Chi-Square Goodness-of-FitTest calculations were computedon participant s

preference selection for each of the eight musical examples, in which eight different

bowing types were used. The purpose of these analyses was to determine whether

participants' responses differed significantly between observed versus expected

number of responses of the trumpet performance played before hearing the violin

performance (TP) or the trumpet performance played after hearing the violin

performance (TPAV) in each of the 8 selections (Siegel & Castellan, 1988).

Significant differences were found in participants' performance selections

in all but one of the examples (See Table 2). Participants selected the TPAV

performance over the TP performance when the following bowing types were

used: Dtach, Spiccato, Lour, Slur, Martel, Staccato, and Slurred Staccato.

36

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Shelly C Cooper and Donald L. Hamann

The only selection in which there was no significant difference was the example

in which the bowing type Coll was used. Based on the results of these analyses it

can be concluded that the trumpet performance in which the performer heard the

violin performance and attempted to match the articulation was determined to be

a significantly better articulation match than when the trumpet player interpreted

the articulation using only the information on the printed music.

Table 2

Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test Summary Results by Bowing Type

Bowing

Bowing

Type

Probability

Chi-Squa e/df

Type Chi-Square/df

Probability

Detache

Dtach

) = =99.32

X2

X2 (1,11

(1,111)

99.32

p < .0001

p < .0001

Spiccato

81.3

X2 (1,

(1,11

111) ) == 81.3

Loure

Lour

X2

X2 (1,11

(1, 111)

) = =50.68

50.68

p< .001

Slur

21.63

X2 (1,

(1,11

111) ) == 21.63

p < .001

Martele

Martel

8.66

X2

X2 (1,

(1,11

111) )==8.66

p < .01

Staccato

3.97

X2

X2 (1,

(1,11

111) )== 3.97

p < .05

Slurred Staccato

3.97

X2

X2 (1,

(1,11

111) )== 3.97

p < .05

Coll

Colle

X2

X2 (1,

(1,11

111) )==.73.73

not significant

significant @@ pp <<.05

.05

In the first research question it was asked whether the written music symbol,

an accent or a dot above a note for example, conveyed the same articulation

interpretation message to a brass player as a to string player? With the exception

of coll, the participants generally preferred the trumpet articulation that was

recorded after the trumpet player heard the violin performance and then made

syllable adjustments to match articulations (See Figure 3). Thus it would appear

that the written manuscript did not convey the same articulation information to

the trumpet player as it did to the violin performer.

In research question two it was asked "Will a brass player performing a musical

selection, given the musical symbols provided on the page, use one type of musical

articulation syllable when playing the example, change that articulation syllable

when asked to listen to and then match a bowed string performance?" Based on

the information provided by the trumpet player, the articulation syllable was either

changed or modified after the performer heard the violin performance (See Figure

4). In every case, the articulation chosen to match the violin performance was

changed after hearing a performance of the example on violin. Indeed, the trumpet

player did modify the articulation syllable after hearing the violin performance

indicating again the difference between the printed-page interpretation of the

articulation versus the articulation after hearing a model of the articulation.

37

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

jntributions to Music Education

Table 3

Selected Trumpet Model Placed in Order from Least Agreement to Most Agreement

Bowing Type Respondents Selected TP Respondents Selected TPAV

Detache

Dtach

3

8

Spiccato

Spiccato

18

Loure Lour

Slur Slur

31

108

108

103

103

18

93

93

31

40

Martele

Martel

Staccato

Staccato

45

Slurred

Slurred

Staccato

80

80

40

71

71

45

66

66

Staccato

45

60

ColleColl

45

66

66

51

51

60

TP

=

Trumpet

Perf

TPAV

=

Trumpet

P

Similarly,

played

on

staccato,

when

page

the

the

th

bo

slurre

brass

instru

case

of

trumpeter'

the

performan

Table 4:

Applied Articulation Syllables as Self-Reported by Trumpet Performer

Bowing

Bowing

Type

Type Respondents

Respondents TP

Selected

Selected

TP

Trumpet

Respondents

Trumpet

Articulation

Selected TPAV

Articulation

Detache

Dtach

Soft "T"

108

Light "D"

Spiccato

Soft "T"

103

Light "T"

Loure

Lour

18

Light "D"

93

"D"

Slur

31

"D"

80

Soft "T"

Martele

Martel

40

arpw

71

Soft "T"

Staccato

45

66

Hard "D"

Slurred Staccato

Colli:

Coll

informat

stringed

In

45

"D"

66

Light "D"

60

Hard "D"

51

"D"

TP = Trumpet Performance

TPAV = Trumpet Performance After Hearing Violin Performance

For the examples that featured the bowings of staccato and slurred staccato,

the margin of participant choice between trumpet performances (printed page

38

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Shelly C Cooper and Donald L, Hamann

versus those played after the violin recording was heard) were not as great as

the differences with the bowings dtach, slur, martel, spiccato, lour, and coll,

with 41% of respondents selecting the trumpet performance as interpreted by the

written page and 59% of respondents selecting the trumpet performance modified

to match the violin. However, even though these differences were smaller, they

were markedly different, indicating a difference between a performance from a

printed page versus a performance having heard the sound source. The coll bow

marking example was the only one in which more respondents selected the trumpet

articulation/performance produced before hearing the violin model and from the

indications on the printed music as a better match rather than the adjusted trumpet

performance. Although, with 54% and 46% variation respectively, it was a small

margin of difference and no significant difference was found between respondents

selections indicating the differences may well have been due to chance.

Using the respondent demographic information, chi-square analyses were

computed to determine whether any differences occurred by string versus non

string players, undergraduate versus graduate students, or according to the

individuals number of years studying an instrument. No significant differences

were identified by string versus non-string players. Due to a lack of adequate

cell size or disparity of cell size, it was not feasible to complete analyses between

undergraduate and graduate students or to identify differences according to the

individual's number of years studying an instrument.

Discussion and Implications

One of the factors involved in uniformity of sound among winds and strings

is articulation. If attacks and releases of all pitches are consistent, when orchestral

ensemble members are provided passages of similar articulation indications, then

enhanced sound uniformity would be achieved. Based on the results of the Chi

Square Goodness of Fit Tests, it was found that the written musical examples did

not convey the same information as did the performance given after hearing the

violin performance of the example. In all but one example, participants chose the

trumpet performance given after hearing the violin performance as best matching

that articulation. The question of whether musical notation adequately conveys

enough information to best produce articulation uniformly is certainly brought

into question based on this study.

An orchestra directors' awareness of the utilization of different syllables by

wind players remains as crucial as a directors' awareness of string players' bowings

(Hamann 8c Gillespie, 2009). While considerable time is generally spent on the

uniformity of bowingsincluding consistency of attacks and releases within and

39

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Contributions to Music Education

between string sections, resulting hopefully in constancy of articulations and

evenness of sound among the stringsis the same amount of emphasis placed

on consistency of articulation between strings and winds, or should it be? From

this study, it appears that attention to articulation consistency between a violin

and trumpet player can be perceived by listeners. Even when similar musical

indications were presented in the musical score, the match of articulation between

the trumpet and violin players was consistently better after an articulation model

was provided to the trumpet performer. In other words, the musical indications in

a score do not insure uniformity of sound for musicians. Phillips (2002) recognizes

the need for brass players to ". . . develop articulations of every possible variety

by utilizing all the vowels and consonants that have musical application of the

communicative art of music" (p. 29). Hence, in ensemble situations the issue of

articulation uniformity may need to be addressed by the leader of that ensemble,

especially when the ensemble involves both wind and string players.

The results of this study imply that a better rehearsal strategy for unified

articulations across sections would be listening to aural models and then

having ensemble members attempt accurate imitations. Whitener also (1990)

identified the "concept of sound" as developed only through careful listening.

Future research is needed for determining the most effective delivery method

aural/visual versus visual-onlyin assisting trumpets imitate the articulation

of a violin performance during rehearsals: (a) by reading the same musical

articulations in print, or (b) by imitating an aural model of a performance of the

same articulations performed by a violinist.

One of the more striking findings in this study was that the common string

bowings, dtach and martel, which are commonly introduced as some of the

first bowing articulations for string players, were the most difficult to match by the

trumpet player given only the musical score indications. Specifically problematic

articulations for the trumpet player to match from the printed notation were

dtach (an on the string stroke), spiccato (an off the string stroke), lour (on the

string) and to some extent the slur (on the string) and martel (on the string).

If similar results were found in future studies, this could indicate a

type of articulation disconnect perhaps not only among trumpet and violin

players interpretation of articulation from the printed score, but perhaps such

nonconformity would extend to all wind instruments. The resultant disconnect

would lead to a lack of sound uniformity within the ensemble which would need

to be addressed by the group's director.

It is important to note the limitations of this study with one violinist and one

trumpet player. Might other performers have played these excerpts differently?

40

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Shelly C. Cooper and Donald L. Hamann

Would use of a different brass instrument impact the results? Another pertinent

question to ask is whether instrumentalists can be taught a systematic approach to

articulation description that might be useful in rehearsal. Is it feasible that when

a trumpet player performs a musical example in which a violinist would normally

use a dtach stroke, that a "light D" syllable would consistently match a violin

performance of the same? Future research could address testing various articulation

syllables to determine whether one or more trumpet articulation syllables would be

perceived to be a "best" match for bowed-string articulations. Is there a universal

syllable language among trumpet players? For example, does a "light D" syllable

possess an identical meaning to all trumpet players? What about other syllables

such as "dah," "tah," "tee," and so forth? If a universal syllable language does exist

among trumpet players, would this extend to all brass instruments? In addition,

researchers could determine whether there are particular woodwind articulation

syllables that consistently match particular bowed-string articulations or whether

there are any articulation syllables that convey a universal articulation language.

Results from this baseline study indicate that a director of a symphonic

orchestra cannot assume that similar print articulations will result in similar

performances by trumpets and strings. These results support the statement by

Hamann & Gillespie (2009) that "Seemingly similar markings can result in

different articulations, depending on whether it is being played by a string or

brass/woodwind player" (136). It would appear that printed-page articulations do

not convey the same meaning to a violinist as to a trumpet player and that different

trumpet syllables result in performances perceived as poorer or better articulation

matches with violin performances of identical musical examples. Whitener (1990)

notes that a brass player can reproduce a desired sound only after "... the passage is

visualized or heard in the 'mind's ear'" (p. 112). While ensemble directors may also

address the issues of articulation among and between various sections within any

given ensemble, the need to increase efforts in articulation and sound uniformity

are supported by this study.

Uniformity of sound is one of the issues that directors strive to achieve within

their ensembles. When articulations are consistent among and between various

sections of any ensemble sound uniformity is enhanced. However, the musical

score may not be the final conveyance of information musicians need to achieve

articulation uniformity. Individuals in chamber ensembles, as well as directors in

orchestras and bands, not only need to be aware of the limitations of the musical

score in terms of articulation uniformity, but also need to have the knowledge

and skill to address this issue. "A player's musicality is the main factor affecting

articulation as it is in most areas of performance" (Snell, 2001, p. 62). It is hoped

41

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Contributions to Music Education

that findings in this study will begin to assist musicians in improving ensemble

clarity through articulation unity and through the interpretation of various

articulation indications in a music score.

Submitted September 14, 2009; Accepted April 16,2010.

References

Allen, M. L. (2003). A pedagogical model for beginning string class instruction:

Revisited. In D. Littrell Editor, Teaching music through performance in orchestra

(pp. 3-14). Chicago, IL: GIA Publications.

Bachelder, D., & Hunt, N. (2002) Guide to teaching brass. 6th ed. New York, NY:

McGraw Hill.

Bundy, O. R. (1987). Instrumentalists' perception of their performance as measured by

detection of pitch and rhythm errors under live and recorded conditions. (Doctoral

dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University, 1987). AAT 8727984.

Colwell, R.J. &Goolsby,T. (1992). The teaching of instrumental music. 2nd ed. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Dickey, M. R. (1991). A comparison of verbal instruction and nonverbal teacher

student modeling in instrumental ensembles. Journal of Research in Music

Education, 39,132-142.

Dickey, M. R. (1992). A review of research on modeling in music teaching and

learning. Bulletin of the Councilfor Research in Music Education, 113,27-40.

Dillon, J. (2008). Playing beyond the score: Thoughts on teaching effective

musicianship. In D. Littrell Editor, Teaching music through performance in

orchestra (pp. 3-8). Chicago, IL: GIA Publications.

Galamian, I. (1985). Principles of violin playing and teaching (2nd ed.). Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Gillespie, R., & Hamann, D.L. (1998). The status of orchestra programs in the

public schools. Journal of Research in Music Education, 46, 75-86.

Goolsby, T.W. (1997). Verbal instruction in instrumental rehearsals: A comparison of

three career levels and preservice teachers. Journal of Research in Music Education,

45(1), 21-40.

Hamann, D.L & Gillespie, R. (2009). 2nd edition. Strategiesfor teaching strings: Building

a successful string and orchestra program. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

42

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Shelly C Cooper and Donald L. Hamann

Hamann, D.L., Gillespie, R., & Bergonzi, L. (2002). Status of orchestra programs in

the public schools. Journal of String Research 2, 9-35.

Hewitt, M.P. (winter 2001). The effects of modeling, self-evaluation, and self-listening

on junior high instrumentalists' music performance and practice attitude. Journal

of Research in Music Education, 49, 307-322

Hunt, A. (1989). Advice for instrumental music teachers. Music Educators Journal, 75

(8), 39-41.

Kepner, C.B. (1986). The effect of performance familiarity, listening condition, and

type of performance error on correctness of performance error detection by 50 high

school instrumentalists as explained through a sensory blocking theory. Ph.D.

diss., Kent State University, Ohio. Retrieved March 13,2009, from dissertations

Sc theses: full text database, (publication no. Aat 8617076).

Klotman, R.H. (1996). 2"d Edition. Teaching strings. New Yorlc Schirmer Books.

Kopiez, R. (2002). Making music and making sense through music: Expressive

performance and communication. In R. Colwell Sc C. Richardson (Eds.), The

new handbook of research on music teaching and learning (pp. 522-541). New

York: Oxford University Press.

Leonhard, C., Sc House, R.W. (1972). Foundations and principles of music education.

New YorlcMcGraw Hill.

Meyer, L.B. (1956). Emotion and meaning in music. Chicago, IL: University of

Chicago Press.

Mueller, H.C. (1967). Learning to teach through playing: A brass method Ithaca, NY:

Ithaca College.

Phillips, H.W. (1992). The art of tuba and euphonium. Secaucus, NJ: Summy-Birchard.

Puopolo, V. (1971). The development and experimental application of self

instructional practice materials for beginning instrumentalists. Journal of Research

in Music Education, 19,342-349.

Reimer, B. (1989). A philosophy of music education (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall.

Rolland, P. (1974). The teaching ofaction in string playing: Developmental and remedial

technique [for] violin and viola. Urbana: Illinois String Research Associates.

Rosenthal, R. K. (1984). Effects of guided model, model only, guide only, and practice

only on performance. Journal of Research in Music Education, 32, 265-273.

Schnoor, N.H. (2002). Incorporating strategies designed to develop aesthetic sensitivity

into band rehearsals. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 21,2-9.

doi: 10.1177/87551233020210020101

43

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

itributions to Music Education

Siegel, S. c Castellan, N.J. Jr. (1988). Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences.

2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Snell, H. (2001). The trumpet: Its practice and performance; a guide for students. West

Yorkshire: Kirkless Music.

Sullivan, J., (2006). The effects of syllabic articulation instruction on woodwind

articulation accuracy. Contributions to Music Education, 33, 59-70.

Swanwick, K. (1979). A basis for music education. New York: Roudedge.

Whitener, S. (1990). A complete guide to brass: Instruments and pedagogy. New York,

NY: Schirmer.

Zrcher, W. (1975). The effect of model-supportive practice on beginning brass

instrumentalists. In C. Madsen, R. D. Greer, &c C. H. Madsen (Eds.), Research

in music behavior: Modifying music behavior in the classroom (pp. 131-138).

New York: Teachers College Press.

44

This content downloaded from 199.212.66.25 on Tue, 11 Oct 2016 15:19:31 UTC

All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- 2001 Visualization of Brass Players'Warm Up by Infrared ThermographyDokument7 Seiten2001 Visualization of Brass Players'Warm Up by Infrared ThermographyEmilio Bernardo-CiddioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clarke The Debutante Cornet SoloDokument9 SeitenClarke The Debutante Cornet SoloDM DM100% (5)

- Trumpet Syllabus RCM 2013Dokument84 SeitenTrumpet Syllabus RCM 2013Emilio Bernardo-Ciddio75% (12)

- Oh Danny BoyDokument2 SeitenOh Danny BoyEmilio Bernardo-CiddioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- A Study On The Factors of Job Satisfaction Among Owners of Small and Medium-Sized Turkish BusinessesDokument14 SeitenA Study On The Factors of Job Satisfaction Among Owners of Small and Medium-Sized Turkish BusinessesAri WibowoNoch keine Bewertungen

- AREVA - Fault AnalysisDokument106 SeitenAREVA - Fault AnalysisAboMohamedBassam100% (1)

- Roughness Parameters: E.S. Gadelmawla, M.M. Koura, T.M.A. Maksoud, I.M. Elewa, H.H. SolimanDokument13 SeitenRoughness Parameters: E.S. Gadelmawla, M.M. Koura, T.M.A. Maksoud, I.M. Elewa, H.H. SolimanPatrícia BarbosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Key Account ManagementDokument75 SeitenUnderstanding Key Account ManagementConnie Alexa D100% (1)

- Class Field Theory, MilneDokument230 SeitenClass Field Theory, MilneMiguel Naupay100% (1)

- Ann Radcliffe Chapter 1 ExtractDokument2 SeitenAnn Radcliffe Chapter 1 ExtractlinsayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychological Science: Facial Expressions of Emotion: New Findings, New QuestionsDokument6 SeitenPsychological Science: Facial Expressions of Emotion: New Findings, New QuestionsIoana PascalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Circles and SquaresDokument15 SeitenCircles and Squaresfanm_belNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sciography 1Dokument4 SeitenSciography 1Subash Subash100% (1)

- First Pre-Title Defense OldDokument15 SeitenFirst Pre-Title Defense OldNicolai Ascue CortesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Silent Way MethodDokument8 SeitenThe Silent Way MethodEbhy Cibie 'gates'100% (1)

- Air Pollution University Tun Hussein Onn MalaysiaDokument16 SeitenAir Pollution University Tun Hussein Onn Malaysiahanbpjhr50% (2)

- Theater Level WargamesDokument148 SeitenTheater Level WargamesbinkyfishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan - Bullying 3Dokument3 SeitenLesson Plan - Bullying 3api-438012581Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2019-3 May-Paschal Mat & Div Lit Hymns - Bright Friday - Source of LifeDokument8 Seiten2019-3 May-Paschal Mat & Div Lit Hymns - Bright Friday - Source of LifeMarguerite PaizisNoch keine Bewertungen

- QuarksDokument243 SeitenQuarksManfred Manfrito100% (1)

- Proiect de LectieDokument4 SeitenProiect de LectieBianca GloriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mbti Ge MbtiDokument6 SeitenMbti Ge MbtiBALtransNoch keine Bewertungen

- NepotismDokument9 SeitenNepotismopep77Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gold in The CrucibleDokument5 SeitenGold in The CrucibleGraf Solazaref50% (2)

- Bob Plant - Derrida and PyrrhonismDokument20 SeitenBob Plant - Derrida and PyrrhonismMark CohenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation On Seven CsDokument36 SeitenPresentation On Seven Csprateekc2967% (3)

- Teaching and Teacher Education: Jo Westbrook, Alison CroftDokument9 SeitenTeaching and Teacher Education: Jo Westbrook, Alison CroftVictor PuglieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurship: Quarter 1 - Module 1: Key Components and Relevance of EntrepreneurshipDokument28 SeitenEntrepreneurship: Quarter 1 - Module 1: Key Components and Relevance of EntrepreneurshipEDNA DAHANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theory of RelativityDokument51 SeitenTheory of RelativityZiaTurk0% (1)

- BlazBlue - Phase 0Dokument194 SeitenBlazBlue - Phase 0Ivan KirinecNoch keine Bewertungen

- HerzbergDokument16 SeitenHerzbergIrish IsipNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cheat Sheet Character Creation Rouge TraderDokument11 SeitenCheat Sheet Character Creation Rouge TraderOscar SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Question Performance Management Question PaperDokument5 SeitenPractice Question Performance Management Question Paperhareesh100% (1)

- AnaximanderDokument14 SeitenAnaximanderRadovan Spiridonov100% (1)