Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

1 s2.0 S1053482216300146 Main

Hochgeladen von

nasirOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1 s2.0 S1053482216300146 Main

Hochgeladen von

nasirCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

HUMRES-00536; No of Pages 13

Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Human Resource Management Review

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/humres

Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement

in the prediction of employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic

path analysis

Michael M. Mackay a,, Joseph A. Allen b, Ronald S. Landis c

a

b

c

Department of Counseling, Educational Psychology and Research, Ball Hall 307C, The University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152, United States

Department of Psychology, University of Nebraska at Omaha, 6001 Dodge Street, Omaha, NE, United States

Department of Psychology, Illinois Institute of Technology, 3105 S. Dearborn St., Life Sciences #252, Chicago, IL 60616, United States

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 28 April 2015

Received in revised form 12 March 2016

Accepted 13 March 2016

Available online xxxx

Keywords:

Employee Engagement

Job Attitudes

Meta-Analysis

Job Performance

a b s t r a c t

The current study used meta-analytic estimates and path analysis to examine whether the construct of employee engagement (EE) shows incremental validity in the prediction of employee

effectiveness (a broad measure of performance-related behaviors) over other job attitudes such

as job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. Meta-analytic estimates

between EE and various employee effectiveness indicators were computed from 49 published

correlations representing a total of 22,090 individuals. We combined these estimates with published meta-analytic estimates between employee effectiveness and job attitudes to produce a

meta-matrix representing 1,161 unique correlations. Using this meta-matrix, a series of path

model comparisons produced two results: (1) EE bears low to moderate incremental validity

over individual job attitudes (R2 change of 0.02 to 0.06), and (2) EE bears low incremental

validity over a higher-order job attitude construct representing the combination of other job

attitudes in the prediction of a higher-order employee effectiveness construct (R2 change of

0.01). Given the brevity of popular EE measures, the results suggest EE is better conceptualized

as a higher-order measure of job attitudes that is an effective and concise predictor of employee effectiveness.

Published by Elsevier Inc.

For more than a decade, the construct of employee engagement (EE) has generated vigorous interest among organizational

practitioners and scholars. A literature search (using PsycINFO/Business Source Elite) of the terms employee engagement and

work engagement for the decade 20012011 revealed more than 1,000 results, of which about 80% were non-empirical papers

authored by human resource practitioners. A similar search for the previous decade (19902000) produced a corpus of only 112

articles. This popularity is, in large part, due to EE's empirically demonstrated and also intuitive link with job performance (for a

review, see Macey & Schneider, 2008; Rich, LePine, & Crawford, 2010) and organizational success (Harter, Schmidt, & Hayes, 2002;

Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2009). Dened as a positive, fullling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli, Salanova, Gonzlez-Rom, & Bakker, 2002), EE reects a compilation of

attitudes most human resource professionals deem to be the cornerstones of a highly performing workforce.

Despite the resounding popularity of EE among practitioners, academic researchers have increasingly questioned whether EE is

overlapping with other well-established job attitude constructs (e.g. Harter & Schmidt, 2008, Newman & Harrison, 2008). In particular, the conceptual space of EE is shared with the long-established constructs of job satisfaction, affective organizational

Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: mmmackay@memphis.edu (M.M. Mackay), josephallen@unomaha.edu (J.A. Allen), rlandis@iit.edu (R.S. Landis).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.03.002

1053-4822/Published by Elsevier Inc.

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

commitment, and job involvement (Newman & Harrison, 2008). In fact, some engagement scales developed by consulting companies dene engagement by encompassing elements of job satisfaction. For example, the Gallup Organization denes EE as an

individual employees' involvement and satisfaction with, as well as enthusiasm for, their work, (Harter et al., 2002, p. 269).

The similarities between EE and these job attitudes are also apparent in the way the constructs are assessed. As pointed out by

Newman and Harrison (2008), an examination of the items of the most popular EE survey (B76the Utrecht Work Engagement

Scale, UWES; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003) reveals that many items have closely matching counterparts on measures of the other

job attitudes. The UWES item I am enthusiastic about my job is almost identical to the Most days I am enthusiastic about

my work item that appears on a longstanding measure of job satisfaction (Overall Job Satisfaction Scale, OJS; Brayeld &

Rothe, 1951). And the UWES item I get carried away when I am working matches the I am very much involved personally

in my work item that appears on the Job Involvement Survey (JIS; Lodahl & Kejner, 1965).

Given these similarities, the purpose of this study was to investigate the incremental validity of EE when accounting for other

potentially overlapping job attitudes. Using meta-analytic techniques, path analyses, and building upon EE theory generally (Kahn,

1990), we propose that EE indeed is related to important job performance variables (i.e., focal performance, contextual performance) beyond other individual job attitudes. Further, taking into consideration the compatability principle (Ajzen, 1988; Ajzen

& Fishbein, 1980), we make the case that EE may be better identied as a higher-order construct that efciently predicts employee

effectiveness, a higher-order measure of performance-related indicators dened as the tendency to contribute desirable inputs towards one's work role (Harrison, Newman, & Roth, 2006, p. 309). In essence, EE may serve as a more efcient and effective way

to capture employee attitudes that predict indicators of employee effectiveness such as focal performance, contextual performance, turnover intention, and absenteeism.

1. Employee engagement research and theory

In a seminal paper, Kahn (1990) dened employee engagement as the degree to which individuals invest their physical, cognitive, and emotional energies into their role performance. According to Kahn, engaged individuals are psychologically present,

attentive, connected, integrated, and focused in their role performances. The contemporary denition of engagement embraces

a highly similar meaning, dening engagement as a positive work-related state of mind comprised of vigor, dedication, and

absorption (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Vigor refers to high levels of energy, the willingness to invest effort, and persistence at

work-related tasks. Dedication relates to feelings of involvement in one's work and the experience of enthusiasm, inspiration,

pride, and challenge. Lastly, absorption is characterized by full concentration, immersion, and engrossment in one's work whereby

time passes quickly and one has difculties detaching oneself from work.

Some of the contextual predictors of EE are jobs that provide social support, performance feedback, autonomy, learning opportunities, and task variety (Christian, Garza, & Slaughter, 2011). High levels of engagement emerge in such work contexts because

they allow employees to fulll basic human needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competence (Deci & Ryan, 1985). According to

the Job Demands-Resources model (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Van Rhenen, 2009) EE and burnout are diametric opposites of a single dimension: resources such as social support and frequent feedback foster engagement while work demands such as time, task difculty, and physical strain predict levels of emotional exhaustion and burnout. An individual can

sustain high levels of engagement only if the resources he or she receives outweigh job demands. Meta-analytic evidence indeed

suggests that EE and burnout are constructs on the opposite ends of a single dimension (Cole, Walter, Bedeian, & O'Boyle, 2012).

However, not all research supports this position, in part because of the variations in how EE is measured and manifested across

samples and studies (Cole et al., 2012).

Due to the intuitive link between EE and employee performance, a number of studies have had success showing that engaged employees perform better than their less-engaged counterparts (Rich et al., 2010). Employee engagement has been linked to higher job

performance ratings, increased in-role performance, organizational citizenship behaviors, personal initiative, higher likelihood of promotion, decreased absenteeism and tardiness, and lower turnover and turnover intention, (for a review, see Macey & Schneider,

2008). Studies have also shown links between EE and less intuitive outcomes such as decreases in work-related health complaints

(Gonzalez-Roma, Schaufeli, Bakker, & Lloret, 2006), workaholism (Schaufeli, Taris, & Bakker, 2006), employee innovativeness

(Schaufeli et al., 2006), and objective markers of nancial performance at the organizational level (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). Interestingly, research also suggests prolonged high levels of EE are rare (Sonnentag, 2003) and that EE can be contagious and cross over

from one coworker to another or within married couples (Bakker & Demerouti, 2009; Bakker & Xanthopoulou, 2009).

In sum, research on EE in the past 25 years has been fruitful in many directions, including examinations of its contextual antecedents and consequences, the links between engagement and burnout, its associations with workaholism, and its divergence

from other constructs. It appears as though EE has enjoyed a signicant amount of success as a new construct in the nomological

network of job-related attitudes. However, given that EE appears to encompass other job attitudes such as job satisfaction, job

involvement, and organizational commitment, its overlap with these job attitudes brings into question whether EE predicts job

performance over-and-above these attitudes. It is to this overlap that we now turn our attention.

1.1. Incremental validity of employee engagement

A small number of studies have indeed examined the overlap between EE and other constructs (e.g., Halbesleben & Wheeler,

2008; Hallberg & Schaufeli, 2006; Schaufeli, et al., 2006; Schaufeli, Taris, & van Rhenen, 2008). Notably, Joseph, Newman, and

Hulin (2010) used meta-analytic means to address this issue and concluded that EE essentially assesses individuals' general

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

attitudes towards their jobs and, hence, subsumes job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. The authors

argued that regardless of whether EE demonstrates discriminant validity over the separate job attitude measures, it does not necessarily have discriminant validity over the combination of the measures.

An alternative method for assessing EE's overlap with other job attitudes is to examine whether it provides incremental validity in the prediction of an important outcome variable such as job performance. Evidence showing that EE offers unique explanatory variance beyond that of other job attitudes would inform the debate because it would address EE's ultimate utility as a

construct. In other words, if empirical evidence showed that EE has incremental validity in predicting job performance, this

would suggest that EE is more than just a simple mix of the three job attitudes and, thereby, a useful and legitimate construct

in its own right. This fact is not lost with leading EE researchers, who themselves suggest [the] crucial question to be answered

is: Has the concept of engagement as dened in academia added value over and above traditional, related concepts?

(Schaufeli & Bakker, 2010, p. 14).

Christian et al. (2011) examined the incremental validity of EE in the context of job performance prediction. Using separate

hierarchical regressions to predict focal and contextual performance, the authors found that EE provided explanatory variance

over-and-above the combination of job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and job involvement. The addition of EE led to

an R2 change of 0.19 in the prediction of focal performance and 0.16 in the prediction of contextual performance. In fact, in

each regression EE was the strongest predictor ( = 0.43 for focal and 0.44 for contextual performance) and the coefcients of

some other predictors were reduced to levels that suggest little practical signicance (i.e., although still statistically signicant,

some beta weights were as low as 0.06 and 0.04).

Building upon the work of Christian et al. (2011), the rst goal of the present study is to examine whether EE has incremental

validity in predicting job performance beyond other job attitudes, but using a larger body of studies of EE to do so. Specically,

this study includes more-recently published work and employs structural equation modeling to assess whether EE bears incremental validity in the prediction of focal and contextual job performance over-and-above other job attitudes (i.e. a metaanalytic path analysis). Thus, the rst research question is as follows:

Research Question 1. Does EE bear explanatory variance in focal and contextual job performance over-and-above other individual

job attitudes?

1.2. Employee engagement as a higher-order construct

If EE does predict job performance over-and-above other individual job attitudes, it may be perhaps better conceptualized as

an efcient higher-order construct. The abbreviated version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli & Bakker,

2003), the most commonly used measure of engagement, is only nine items long. Given that the scale appears to contain elements of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment, it may be an efcient way to broadly assess a number

of underlying job attitudes. It would be remarkable to nd separate measures of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment that were reliable, valid, legally defensible AND only nine items combined.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the debate regarding the uniqueness of EE cannot be convincingly resolved by analyzing whether EE bears incremental validity over other individual job attitudes, as assessed by Research Question 1. Even though

such analyses are informative, a higher-order construct will almost always show incremental validity over one of its lower-order

indicators and thereby appear unique. Due to the fact that EE appears to contain elements of job satisfaction, job involvement, and

organizational commitment, it will likely exhibit incremental validity over any one of these individual indicators. Thus, showing

that EE bears incremental validity over a higher-order job attitude construct (comprising job satisfaction, job involvement, and

organizational commitment) seems essential.

The Christian et al. (2011) study presents compelling evidence for the incremental validity of EE over other job attitudes in the

prediction of focal and contextual job performance. This evidence, however, is based on separate regression analyses for focal and

contextual performance (rather than simultaneously analyzing both types of performance). According to the compatibility principle of attitudes (Ajzen, 1988; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), constructs that have the same level of specicity will exhibit higher relationships than constructs of differing specicities. In other words, the correlation between two broadly dened constructs will be,

all other things being equal, stronger than the correlation between a broad and a specic construct. First-order constructs better

predict other rst-order constructs, second-order constructs better predict second-order constructs, and so on. With regard to EE,

the compatibility principle suggests that the most rigorous test of EE's incremental validity is not in the prediction of only focal

performance, or only contextual performance, but in the prediction of a higher-order construct that includes both types of performance, as well as other indicators such as absenteeism and turnover. We term this construct employee effectiveness, and dene it

via Harrison et al. (2006) as the overall tendency to contribute desirable inputs towards one's work role (p. 309).

The compatibility principle has found empirical support in both organizational (e.g., Judge, Thoresen, Bono, & Patton, 2001)

and non-organizational contexts (Kraus, 1995). More recently, Harrison et al. (2006) demonstrated that a higher-order job attitude construct exhibits better prediction of employee performance if performance is represented by a higher-order construct

that includes focal performance, contextual performance, lateness, absenteeism, and turnover.

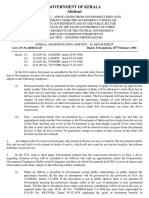

In sum, considering that EE contains elements of other job attitudes (and may therefore be a higher-order construct), the second goal of the present study is to rigorously assess EE's incremental validity is by examining whether it predicts a higher-order

construct of employee effectiveness over-and-above a higher-order job attitude construct (see Fig. 1). Thus, the second research

question is as follows:

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

Fig. 1. Path model used to estimate incremental validity of EE.

Research Question 2. Does EE bear explanatory variance in a higher-order employee effectiveness construct (comprising focal

performance, contextual performance, turnover, and absenteeism) above and beyond a higher-order job attitude construct (comprising job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment)?

The present study therefore contributes to existing literature in the following ways: 1) it provides updated meta-analytic estimates between EE and job performance (focal and contextual) based on a larger number of published estimates (29 in the present study versus 9 in Christian et al., 2011), 2) it provides meta-analytic estimates of the relationships between EE, absenteeism,

and turnover intention, which are currently lacking in the literature, 3) it assesses whether EE bears incremental validity over a

higher-order job attitude construct, which we contend is the most rigorous approach to assessing its incremental validity, 4) in

line with the compatibility principle (Ajzen, 1988; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), it introduces the construct of employee effectiveness,

a higher-order measure of desirable employee behaviors that includes job performance, absenteeism and turnover intention, and

5) it assesses whether EE bears incremental validity not just with respect to the prediction of focal and contextual job performance, but also with respect to the higher-order employee effectiveness construct.

2. Method

To assess the incremental validity of EE, the study required the construction of a meta-analytic matrix of estimates among EE,

job satisfaction, job involvement, affective organizational commitment, focal performance, contextual performance, turnover, and

absenteeism. This resulted in a meta-matrix comprising of 28 meta-analytic estimates. Of these 28 estimates, four correlations

(between EE and each employee effectiveness indicator) were original meta-analytic estimates derived in the current study.

The remaining 24 represent meta-analytic estimates provided by other studies. The following sections describe the procedures

used to produce meta-analytic estimates and the estimation of path models.

2.1. Identication of studies for meta-analysis

To identify studies reporting relationships between EE and the employee effectiveness indicators, a literature search was performed using PsycINFO, Business Source Premier, ABI/INFORM and Web of Science databases for the years 1990 to 2015.1 To ensure the search located all literature relevant to the EE construct, the subject terms/keywords of employee engagement, work

engagement, and job engagement were used. Searches were conducted whereby these three keywords were paired the following

employee effectiveness-related subject terms/keywords: job performance, work performance, task performance, focal performance,

role performance, role behavior, contextual performance, organizational citizenship behavior, prosocial behavior, discretionary behavior,

withdrawal, turnover, turnover intention, retention, quit, lateness, tardiness, truancy, absenteeism, and attendance. A manual search

also reviewed the reference lists of often-cited papers and review articles related to EE.

2.2. Rules for inclusion

To be included in the meta-analysis, a study had to report original data, provide enough information to calculate a correlation

coefcient,2 include sample size information, and assess employee effectiveness via one of the indicators relevant to the present

study. Due to the paucity of research examining the relations between EE and actual turnover, studies that assessed turnover intentions were also included. Studies that used reverse-scored measures of disengagement were not included as it is unclear

whether disengagement is conceptually identical with lack of engagement (for a contrary view, see Gonzalez-Roma et al.,

2006). For studies that reported multiple time points, only time one estimates were included. If a study used multiple measures

The year 1990 was used because it denotes the rst appearance of the EE construct (Kahn, 1990).

For studies that reported beta coefcients and no zero-order correlations, we estimated the correlation by directly imputing beta, a procedure shown to have acceptable accuracy by Peterson and Brown (2005).

2

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

of a single construct or reported facet-level effect sizes (e.g., dedication, absorption, and vigor), a mean correlation coefcient was

calculated from the reported facet-level correlations.

Studies that measured EE via the Gallup Workplace Audit (GWA, The Gallup Organization, 19921999) were not included in

the meta-analysis because the GWA assesses employee perceptions of work characteristics (italics added for emphasis; Harter

et al., 2002, p. 269) rather than affective-level engagement.3

2.3. Meta-analytic procedures

The described rules of inclusion yielded a pool of studies containing 49 unique correlations (N = 22090) for the estimation of

the relationships between EE and the four employee effectiveness indicators (i.e., focal performance, contextual performance,

turnover intention, and absenteeism). To ensure delity in coding, eight of the studies were coded by two researchers. The coders

exhibited over 95% agreement and discrepancies were resolved by re-checking the studies to determine the correct coding.

Hunter and Schmidt's (1990) meta-analytic procedures were used to correct individual correlations for sampling error and unreliability in predictor and criterion measures. In the few cases where Cronbach's alpha was not reported, the mean reliability of

the instrument across all other studies was computed and used as a proxy. No corrections were made for range restriction due to unavailability of this data. Objective measures of absenteeism were considered perfectly reliable and not corrected. Lastly, all measures

of focal and contextual job performance were either supervisor- or coworker-rated (i.e., they were not based on self ratings).

2.4. Identication of studies for path analysis

To estimate the incremental validity of EE over the higher-order job attitude construct (Fig. 1), a meta-correlation matrix was

constructed by combining the meta-analytic estimates derived in the present study with meta-analytic data from published studies. Specically, the four cells in the matrix expressing correlations between EE and each indicator of employee effectiveness represent original meta-analytic estimates derived in the current study. The remaining 24 cells, which represent correlations between

job attitudes and various employee effectiveness indicators, were populated with estimates from published meta-analyses. The

criteria for inclusion for these estimates were that they came from the most comprehensive meta-analyses to date (i.e., were derived from the largest number of original studies) and were also corrected for unreliability in the predictor and criterion. This approach to building meta-analytic matrices in order to estimate path models is recommended by Viswesvaran and Ones (1995)

and has previously appeared in organizational research (e.g.Earnest, Allen, & Landis, 2011, Harrison et al., 2006). The amalgamation of the meta-analytic estimates derived in the present study with existing meta-analytic estimates resulted in a metamatrix that represents 1161 unique correlations. Due to the fact that each cell in the meta-matrix reects a different sample

size, the sample size for estimation of path models was set at the harmonic mean of the meta-matrix (i.e., Nh = 3803, as recommended by Viswesvaran & Ones, 1995).4

2.5. Path analysis procedures

To assess the incremental validity of EE beyond the higher-order job attitude construct, a three-step approach was adapted.

First, a conrmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess indicator loadings and correlations among latent constructs

(Fig. 2). Second, a base model containing no parameter between EE and employee effectiveness was estimated. This model

allowed for the estimation of how well the higher-order job attitude construct predicts employee effectiveness when EE is excluded. Third, a nested model containing a path between EE and employee effectiveness was estimated (Fig. 1) to determine to what

the addition of EE improves explanatory variance in employee effectiveness. The difference in t between the base and nested

models, as well as the individual path coefcients and change in R2, allowed for the estimation of the incremental validity of EE.

The t of all models was estimated using maximum likelihood estimation methods and evaluated using t indices and cutoff

criteria recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999): the chi-square test (critical value of p b 0.05), standardized root mean square

residual (SRMR), comparative t index (CFI), and root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

3. Results

3.1. Research question 1: Does EE bear explanatory variance in focal and contextual job performance over-and-above other individual job

attitudes?

Table 1 presents meta-analytic correlations for EE.5 With the exception of absenteeism, which was considered perfectly reliable, correlations are corrected to unreliability in the predictor and criterion variable. Estimates for focal and contextual

3

The GWA assesses job attributes that are theoretical antecedents of engagement, not the attitude of engagement itself. The inclusion of studies that measure EE via

the GWA therefore had no merit on conceptual grounds.

4

Due to the fact that sample size differed considerably in the cells of the meta-matrix, the path models were also analyzed using the minimum sample size of 824.

Although there were minor changes in overall model t, all p-values remained at b0.001 and the results were the same as those using the harmonic mean sample size.

5

Analyses were conducted to determine whether the type of instrument used to measure EE (UWES versus other instruments) moderated the meta-analytic estimates. In no cases was instrument type a signicant moderator.

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

Fig. 2. Measurement model showing indicator loadings and latent correlations.

performance are based on non-common source estimates only. To address Research Question 1, these correlations were added to

the meta-matrix (see Table 2) to determine whether EE bears incremental validity in the prediction of focal and contextual job

performance when simultaneously compared to each individual job attitude (i.e., separate analyses for job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment). Thus, six sets of path models were estimated, with each set containing a base

model which lacked the path from EE to job performance, and a nested model in which the path was added, allowing the estimation of R2 change due to the addition of the EE path.

Table 3 shows the results of the six models. In all models, the path between EE and focal or contextual performance was statistically signicant (p b 0.001), with standardized path coefcients ranging from 0.16 (when predicting focal performance in a

model with job satisfaction) to 0.31 (when predicting focal performance in a model with job involvement). The total R2 explained

by the models ranged from 0.07 to 0.12. In all models, the correlation between EE and each job attitude was strong, ranging from

0.44 (with job satisfaction) to 0.60 (with job involvement). Notably, addressing Research Question 1, the R2 change for ve of the

six models was between 0.04 and 0.06, which indicates a medium effect by conventional standards (Cohen, 1988). The R2 change

for the other model was 0.02, indicating a small effect. These results suggest the addition of EE to a model containing one of the

other individual job attitudes leads to modest increases in explanatory variance in employee effectiveness.

3.2. Research question 2: Does EE bear explanatory variance in a higher-order employee effectiveness construct over-and-above a higherorder job attitude construct?

The meta-correlation matrix presented in Table 3 was used to estimate the path models estimating the incremental validity of

EE over-and-above a higher-order job attitude construct. For all models, the loading of the EE indicator onto the EE latent construct was xed to 1 to ensure adequate model identication. All results that follow report standardized values. Table 4 presents

a summary of the path analyses.

3.2.1. Measurement model

The measurement model exhibited fair t (Fig. 2). The chi-square was signicant, 2(18) = 1199.50, p b 0.001; however, this was

expected given the large sample size. Other model t statistics indicated generally encouraging t: SRMR = 0.06, CFI = 0.86,

RMSEA = 0.13. All indicators of the higher-order job attitude construct loaded adequately (i.e., N 0.68) and were signicant at

the p b 0.001 level. Indicators of employee effectiveness exhibited somewhat lower loadings, ranging from 0.45 to 0.53, but were

also all signicant at the p b 0.001 level. Notably, the correlation between the EE construct and the higher-order job attitude construct was 0.69, showing that EE is highly correlated with a higher-order construct that represents these three job attitudes.

3.2.2. Path models

To assess the incremental validity of EE above the job attitude construct, a base model was rst estimated which lacked the

path between EE and employee effectiveness. Fit statistics were similar to the measurement model: 2(19) = 1291.19, p b 0.001,

SRMR = 0.06, CFI = 0.85, RMSEA = 0.13 (see Table 4). In this model, the relationship between the overall job attitude construct

Table 1

Meta-analysis of relations between employee engagement and employee effectiveness indicators.

95% condence interval

Focal performance

Contextual performance

Turnover intention

Absenteeism a

80% credibility interval

SE

SD

16

13

17

3

4421

2745

11,359

3565

0.22

0.28

0.30

0.08

0.26

0.32

0.35

0.10

0.04

0.04

0.04

0.07

0.18

0.24

0.43

0.25

0.35

0.40

0.27

0.05

0.11

0.16

0.11

0.22

0.12

0.12

0.49

0.38

0.41

0.52

0.20

0.18

Note. k = number of effect sizes used to compute meta-analytic estimate; N = sample size; r = mean sample-size weighted correlation; = mean correlation

corrected for attenuation in the predictor and criterion, SE = standard error of corrected correlation; SD = standard deviation of corrected correlation; a criterion

measured objectively, corrected for predictor attenuation only.

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

Table 2

Meta-analytic matrix used to estimate the incremental validity of employee engagement.

Category

1.

1. Job satisfaction

2. Org. commitment

k

N

SD

80% CI

3. Job involvement

k

N

SD

80% CI

4. Employee engagement

k

N

SD

80% CI

5. Focal performance

k

N

SD

80% CI

6. Contextual performance

k

N

SD

80% CI

7. Turnover intention

k

N

SD

80% CI

8. Absenteeism

k

N

SD

80% CI

0.65a

69

23,656

0.13

0.480.82

0.45b

87

27,925

0.16

0.250.65

0.44c

19

10,054

0.24

0.140.74

0.30d

312

54,471

0.21

0.030.57

0.24e

69

17,672

0.08

0.140.34

0.19f

67

24,566

0.10

0.31 to 0.07

0.15g

17

3767

0.16

0.350.05

2.

3.

0.53h

16

3625

0.13

0.370.69

0.54i

17

11,201

0.05

0.480.60

0.18j

87

20,973

0.10

0.050.31

0.27k

8

1815

0.07

0.180.36

0.23l

67

27,540

0.08

0.33 to 0.13

0.16m

30

5748

0.60n

7

1522

0.11

0.450.74

0.10o

22

5490

0.15

0.100.15

0.24p

6

2828

0.19

0.000.48

0.14q

4

824

cc

cc

cc

cc

0.14r

17

4762

0.13

0.300.02

4.

0.26s

16

4421

0.11

0.120.41

0.32t

13

2745

0.16

0.120.52

0.35u

17

11,359

0.11

0.49 to 0.20

0.10v

3

3565

0.07

0.380.18

5.

6.

7.

0.23w

24

9912

cc

cc

0.15x

72

25,234

0.13

0.320.02

0.29y

49

15,764

0.22z

5

1619

cc

cc

cc

cc

cc

cc

0.26aa

8

957

0.33bb

33

5316

0.09

0.220.44

Note. Correlations represent estimates disattenuated for unreliability. Correlations with focal and contextual performance represent non-common source estimates.

Absenteeism estimates are based on objective measures and considered perfectly reliable. Harmonic N = 3803; SD = standard deviation of corrected correlation;

80% CI = Credibility Interval for ; cc Information not provided in original article or could not be calculated.

Letter superscripts indicate the source of the meta-analytic correlation: a/k Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, and Topolnytsky (2002) affective commitment estimate; b Brown

(1996); c/i/n/o/p/q Joseph et al. (2010); d Judge et al. (2001); e Ilies, Fulmer, Spitzmuller, and Johnson (2009); f/l/x Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner (2000); Lepine et al.

(2002); g Hackett (1989); h Meyer et al. (2002); j Riketta (2002); m derived by Harrison et al. (2006) from original estimates by Mathieu and Zajac (1990) and

Meyer et al. (2002); r Brown (1996); w/z/aa Harrison et al. (2006); y Bycio (1992); bb Mitra, Jenkins, and Gupta (1992); s/t/u/v original estimates, see Table 1.

and employee effectiveness was quite strong ( = 0.57, p b 0.001), explaining 32% of variance. Similar to the measurement

model, the correlation between EE and the job attitude construct was again strong, r = 0.71, p b 0.001.

To assess EE's incremental validity, a model was specied in which path between EE and employee effectiveness was freely

estimated (Fig. 3). All t indices were almost identical to the previous base model: 2(18) = 1199.45, p b 0.001, SRMR = 0.06,

CFI = 0.86, RMSEA = 0.13. A chi-square difference test revealed that the nested model provided a signicant improvement

upon the base model, 2(18) = 91.74, p b 0.001.

Addressing Research Question 2, the R2 for the prediction of employee effectiveness by both EE and the higher-order job attitude construct was 0.33. This represents a 1% increase in explanatory variance between the base and nested models. More noteworthy, the path between EE and employee effectiveness was 0.31 (p b 0.001) and the path between the job attitude construct

and employee effectiveness (0.57 in the base model) dropped to 0.32 (p b 0.001), indicating in this model EE and the higherorder job attitude construct essentially had equal explanatory power in the prediction of employee effectiveness. Similar to the

previous analyses, the correlation between EE and the higher-order job attitude construct was high, r = 0.69, p b 0.001.

Due to the fact that in the previous analysis adding the path between EE and employee effectiveness resulted in only a 1% increase in explanatory variance in employee effectiveness, (and the explanatory variance was almost equally split between EE and

the higher-order job attitude construct), additional analyses were performed to determine if similar effects would hold true for

each individual indicator of employee effectiveness. In other words, various sets of base and nested models with only one employee effectiveness indicator were estimated (e.g., employee effectiveness comprised of only focal job performance). The results of

these analyses corroborated previous results: regardless of which single employee effectiveness indicator was used, the addition

of the path from EE resulted small increases in R2 (0.00 to 0.03), and in each case the correlation between EE and the higher-order

job attitude construct was either 0.69 or 0.70 (see Table 5).

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

Table 3

Path models estimating incremental validity of employee engagement vs. individual job attitudes.

Model

Path

EE vs. job satisfaction predicting focal performance

1. Job satisfaction

2. Employee engagement

EE vs. job satisfaction predicting contextual performance

1. Job satisfaction

2. Employee engagement

EE vs. job involvement predicting focal performance

1. Job involvement

2. Employee engagement

EE vs. job involvement predicting contextual performance

1. Job involvement

2. Employee engagement

EE vs. organizational commitment predicting focal performance

1. Organizational commitment

2. Employee engagement

EE vs. organizational commitment predicting contextual performance

1. Organizational commitment

2. Employee engagement

S.E.

C.R.

Total R2

R2 Change

0.23**

0.16**

0.02

0.02

13.51

9.32

0.44**

0.11

0.02

0.12**

0.26**

0.02

0.02

7.24

15.65

0.44**

0.12

0.06

0.09**

0.31**

0.02

0.02

4.48

16.01

0.60**

0.07

0.06

0.08**

0.28**

0.02

0.02

3.91

14.35

0.60**

0.11

0.05

0.06*

0.23**

0.02

0.02

3.01

12.37

0.54**

0.07

0.04

0.14**

0.25**

0.02

0.03

7.57

13.57

0.54**

0.12

0.04

Note. *p b 0.01; **p b 0.001; r = correlation between EE and the higher-order job attitude construct; C.R. = critical ratio.

R2 Change = change due to addition of path between EE and employee effectiveness.

4. Discussion

In review, the purpose of this study was to investigate the incremental validity of EE when accounting for potentially overlapping

job attitudes. Research Question 1 assessed whether EE predicted focal and contextual job performance over-and-above the individual job attitudes of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. The ndings show that when entered alongside

each individual job attitude, EE was a signicant predictor of employee effectiveness, with paths ranging from 0.16 to 0.31. The R2

change in ve of the six models was of medium magnitude (0.04 to 0.06; Cohen, 1988), suggesting that EE bears some incremental

validity in the prediction of focal or contextual job performance. This is especially salient considering the total R2 in these models was

not large, ranging from 0.07 to 0.12. Thus, when EE is contrasted against individual job attitudes, it appears to have moderate incremental validity in the context of predicting job performance. Notably, the correlation between EE and each job attitude was medium

to strong, ranging from 0.44 to 0.60. Although these correlations are not strong enough to suggest that EE is redundant with the other

job attitudes, they are also not weak enough to make a strong argument for EE's uniqueness.

Thus, the results pertaining to Research Question 1 provide some evidence for the incremental validity of EE over-and-above

individual job attitudes. That said, nding that EE relates to performance beyond any single job attitude neglects the fact that in

most research and practical uses of such measures, rarely are single job attitudes measured alone. Rather, researchers and practitioners often include a variety of job attitudes on a single survey or measurement process (e.g. Saks, 2006). Thus, the purpose of

Research Question 2 was to determine if EE predicts employee effectiveness over-and-above a higher-order job attitude construct

that comprised all three job attitudes.

The path models showed that the addition of a path from EE to employee effectiveness essentially split the explanatory variance

equally between EE and the higher-order job attitude construct. In the base model, which did not have a path from EE to employee

effectiveness, the path for the higher-order job attitude construct was 0.57. When a path from EE to employee effectiveness was

added, the higher-order job attitude path dropped to 0.32 and the path from EE to employee effectiveness was 0.31 (Fig. 2). More importantly, the explanatory variance in employee effectiveness increased only from 0.32 to 0.33, indicating that the addition of the EE

path resulted in a 1% increase in the ability to predict employee effectiveness. These results suggest that EE bears a very small amount

of incremental validity over a higher-order job attitude construct that includes job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational

commitment.

Furthermore, the correlation between EE and the higher-order job attitude construct was high in all path models: 0.69 in the

measurement model, 0.71 in the base model, and 0.69 in the nested model. Additional analyses in which the employee effectiveness construct was broken down into its individual components (i.e., the outcome variable was one of the four employee

Table 4

Path models estimating incremental validity of employee engagement vs. a higher-order job attitude construct.

Model

df

CFI

SRMR

RMSEA

90% CI

LH

Base model with no path from EE

Nested model with EE path included

1291.19

1199.45

19

18

0.85

0.86

0.06

0.06

0.133

0.131

0.127

0.125

2Change (df)

0.139

0.138

91.74 (1)*

Note. CFI, comparative t index; SRMR, standardized root-mean-square residual; RMSEA, root-mean-square error of approximation, 90% CI = 90% RMSEA condence interval; *signicant at p b 0.001.

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

Fig. 3. Nested path model showing the prediction of Employee Effectiveness.

effectiveness indicators; Table 5) presented similar results: the addition of EE lead to small increases in R2 (0.00 to 0.03), and the

correlation between EE and the higher-order job attitude construct ranged from 0.69 to 0.70. Given these results, it appears as

though EE may be best conceptualized as a construct that encompasses the other three job attitudes.

Lastly, it is worthwhile to note the amount of variance explained by these models. Models in which the outcome variable was

a single indicator (e.g., only focal performance was used; Table 5) had relatively low total R2, ranging from 0.04 to 0.13. In comparison, the model in which the outcome variable was a higher-order employee effectiveness construct representing focal performance, contextual performance, turnover intention, and absenteeism had a much higher R2 of 0.33. These results offer further

evidence that, in line with the compatibility principle (Ajzen, 1988; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980), EE may be best conceptualized as

a higher-order construct. In other words, EE, which appears to encompass other job attitudes, is a better predictor of a higherorder employee effectiveness construct than of lower-facet indicators such as focal performance.

The key implication of the results pertaining to Research Question 2 is that EE may be a more efcient method of capturing job

attitudes and connecting them meaningfully to employee effectiveness. The higher-order job attitude construct, as presented in

the present study, is a combination of three measures of individual job attitudes whereas EE is almost without exception a single

measure. An item comparison across existing measures of job attitudes shows that EE is assessed with fewer items than the corresponding measures of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. So, in terms of survey space and time,

it is more efcient. The following sections discuss how the current results inform the EE-job attitudes debate.

4.1. Implications for research and practice

The current ndings hold key implications for research on EE and employee effectiveness. Even though EE overlaps considerably with a higher-order construct of job attitudes, it is in no way an impractical construct. The results suggest EE is potentially a

more direct (i.e., more tightly conceptualized) predictor of employee effectiveness than the aggregate of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. Furthermore, the study's results in a sense ip the question from Is it worthwhile

to add a measure of EE if already measuring other job attitudes? to, Is it worthwhile to add measures of other job attitudes if

already measuring EE? Such a question becomes especially valid when the length of a typical EE scale is taken into consideration.

The most popular measure of EE, the UWES (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003), contains either 9 or 17 items, depending on the version. It

thus represents a quick and efcient way of assessing a key predictor of employee effectiveness and arguably makes the addition

of other job attitude measures unnecessary. Given the small increase in explanatory variance these other measures would bring,

their addition would bear little practical benet to organizations. Thus, when considering its ease of assessment, the advantages of

EE become considerable. These results will be welcome news to practitioners, who are always interested in nding brief but

meaningful methods of assessing employees' attitudes regarding their jobs.

Table 5

Path Models Estimating Incremental Validity of Employee Engagement in Prediction of Specic Employee Effectiveness Indicators.

Model

EE vs. higher-order job attitude construct predicting focal performance

1. Higher-order job attitude construct

2. Employee engagement

EE vs. higher-order job attitude construct predicting contextual performance

1. Higher-order job attitude construct

2. Employee engagement

EE vs. higher-order job attitude construct predicting turnover intention

1. Higher-order job attitude construct

2. Employee engagement

EE vs. higher-order job attitude construct predicting absenteeism

1. Higher-order job attitude construct

2. Employee engagement

Path

S.E.

C.R.

Total R2

R2 Change

0.15**

0.16**

0.04

0.02

5.66

6.61

0.70**

0.08

0.00

0.22**

0.17**

0.04

0.02

8.31

7.30

0.69**

0.13

0.00

0.03

0.33**

0.04

0.02

-1.25

-14.12

0.69**

0.12

0.03

0.25**

0.074*

0.04

0.03

-9.19

3.01

0.69**

0.04

0.01

Note. * p b 0.01; ** p b 0.001; r = correlation between EE and the higher-order job attitude construct; C.R. = critical ratio.

R2 Change = change due to addition of path between EE and employee effectiveness.

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

10

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

Organizations continue to use climate surveys to investigate employee attitudes and the organizational environment to determine ways of increasing morale and employee effectiveness. This study's ndings suggest that organizations that aim to boost

workforce productivity may nd it benecial to create an environment and organizational culture that is likely to promote EE.

Specically, organizations should foster empirically-supported antecedents of EE, such as autonomy, task variety, managerial support, fair and timely performance feedback, and ongoing learning opportunities (Christian et al., 2011).

4.2. Limitations and future directions

The current study is not without limitations which provide additional opportunities for future inquiry. First, as noted in the results

section, the t indices for many of the models had encouraging t, but did not reach conventional levels of t that are typically desired

in studying individual samples. The lack of t could be a result of the variety of samples included in the analysis including samples

from various countries, industries, and companies. This sample-specic variety introduces error that is not easily accounted for or

modeled in a meta-analytic framework. Given that the purpose of the study was not about model t, per se, but about specic relationships and EE's incremental validity, the overall model t is more of a backdrop to other more specic hypotheses.

Second, a meta-analytic path analysis rests on the assumption that matrices (be they correlations or variance-covariance),

being combined across studies are homogeneous. Due to the fact that the meta-matrix in the current study was populated

with estimates from other meta-analytic studies, this assumption cannot be readily tested as these studies provided only one

cell in the larger matrix. Of note, these issues are magnied to the degree that xed-effects methods are used to estimate the

meta-analytic values. In the present study, the meta-analytic correlations between EE and the four indicators of employee effectiveness were generated through random-effects models and the credibility intervals associated with the estimates are not particularly wide. For the estimates taken from other studies, we note that the majority were also conducted using Hunter and

Schmidt's (1990) meta-analytic procedures that employ random effects. Thus, there is some condence that signicant moderation is not present for any of the effects. Nonetheless, we suggest some degree of caution when interpreting the current results

given that we were not able to convincingly test the homogeneity assumption.

A third limitation of the study is that the correlations that populate the meta-matrix are based on cross-sectional research,

leading to the inability to conclusively address causality (Rosopa & Stone-Romero, 2008). Although it is foreseeable that job attitudes are antecedents of employee effectiveness, research suggests the relationships are at least to some extent bidirectional

(Riketta, 2008). A future meta-analysis that includes only longitudinal research and uses cross-lagged panel analysis could be

helpful in clarifying both the magnitude and direction of effects between the study variables; however, researchers have noted

that cross-lagged analyses do not provide a sound basis for causal inferences (Rogosa, 1980).

Another limitation related to the cross-sectional nature of the data is that the results presented here may suffer from issues

related to common-method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Common-method bias refers to the ination of

relationships between variables measured using the same methodology, in this case self-report scales. Although some of the estimates in the meta-matrix come from studies that were not susceptible to this bias (i.e., all estimates regarding focal and contextual performance are based only on non-common source estimates), others were not. Many of these studies engaged in practices

recommended by current scholars to mitigate common method bias (Conway & Lance, 2010); regardless, their presence in our

meta-matrix may have produced inated relationships.

We concede that this is a notable limitation of the present meta-analysis. That said, it is reasonable to expect that the amount

of ination is similar in any study that uses common-source data. In other words, all estimates in the meta-matrix that are based

on common-source studies are likely overinated to a comparable extent, akin to adding a constant across-the-board. If this assumption is tenable, then the results of the path analyses still make a viable comment on the incremental validity of EE, although

the magnitude of all path coefcients may be inated.

Future studies should also examine a broader array of employee effectiveness indicators. For example, the conceptual space of

the employee effectiveness construct could also include employee burnout and health, which have empirically-demonstrated links

with job performance (e.g., Bakker, Demerouti & Lieke, 2012; Bakker, Tims & Derks, 2012; Schaufeli et al., 2006). Other promising

additions are counterproductive work behavior and workplace deviance (Bennett & Robinson, 2003) as well as organizational

safety (see Nahrgang, Morgeson, & Hofmann, 2011). The inclusion of these variables would further expand the employee effectiveness construct and cast clearer light on its relationship with EE and other job attitudes.

Lastly, the current study only included research that assessed performance at the individual level of analysis. Studies have

demonstrated that EE is linked to improved collective and business-unit performance (e.g. Salanova, Agut, & Peir, 2005,

Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). Employee engagement has also been shown to crossover from one individual to another (Bakker &

Demerouti, 2009), leaving open the possibility that engaged employees can infect their coworkers and drive group-level performance. Given the fact that most jobs are performed in the context of coworkers, and that HR practitioners are ultimately interested in explaining performance at high levels of analysis, these are viable areas of future research.

5. Conclusion

The present study investigated the incremental validity of EE when accounting for potentially overlapping job attitudes. Results show that EE offers moderate incremental validity in the prediction of employee effectiveness over-and-above the individual

job attitudes of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment. However, when contrasted against a higherorder job attitude construct (i.e., the combination of the three job attitudes), EE adds very little additional variance in the

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

11

prediction of employee effectiveness. Furthermore, EE is highly correlated with the higher-order job attitude construct. Given the

brevity of a typical EE measure, the results therefore suggest that EE may be a highly effective method of assessing an employee's

overall attitudes towards his or her job, suggesting EE has utility for use in organizations.

References6

Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

*Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2009). The crossover of work engagement between working couples. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24, 220236.

Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2009). The crossover of daily work engagement: Test of an actorpartner interdependence model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94,

15621571.

*Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Lieke, L. (2012a). Work engagement, performance, and active learning: The role of conscientiousness. Journal of Vocational Behavior,

80(2), 555564.

*Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012b). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations, 65(10),

13591378.

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2003). The past, present, and future of workplace deviance research. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (pp. 247281) (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Brayfield, A. H., & Rothe, H. F. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 35, 307311.

Brown, S. P. (1996). A meta-analysis and review of organizational research on job involvement. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 235255.

Bycio, P. (1992). Job performance and absenteeism: A review and meta-analysis. Human Relations, 45(2), 193221.

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel

Psychology, 64(1), 89136.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cole, M. S., Walter, F., Bedeian, A. G., & O'Boyle, E. H. (2012). Job burnout and employee engagement: A meta-analytic examination of construct proliferation. Journal of

Management, 38(5), 15501581.

Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business

Psychology, 25, 325334.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Earnest, D. R., Allen, D. G., & Landis, R. S. (2011). Mechanisms linking realistic job previews with turnover: A meta-analytic path analysis. Personnel Psychology, 64(4),

865897.

Gonzalez-Roma, V., Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Lloret, S. (2006). Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles? Journal of Vocational

Behavior, 68, 165174.

Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463488.

Hackett, R. D. (1989). Work attitudes and employee absenteeism: A synthesis of the literature. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 62, 235248.

*Halbesleben, J., & Wheeler, A. (2008). The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work & Stress, 22(3),

242256.

*Hallberg, U., & Schaufeli, W. (2006). Same same but different? Can work engagement be discriminated from job involvement and organizational commitment?

European Psychologist, 11(2), 119127.

Harrison, D. A., Newman, D. A., & Roth, P. L. (2006). How important are job attitudes? Meta-analytic comparisons for integrative behavioral outcomes and time sequences. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 305326.

Harter, J., & Schmidt, F. (2008). Conceptual versus empirical distinctions among constructs: Implications for discriminant validity. Industrial and Organizational

Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 1(1), 3639.

Harter, J., Schmidt, F., & Hayes, T. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A metaanalysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268279.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling,

6, 155.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (1990). Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Ilies, R., Fulmer, I., Spitzmuller, M., & Johnson, M. D. (2009). Personality and citizenship behavior: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology,

94(4), 945959.

Joseph, D. L., Newman, D. A., & Hulin, C. L. August, (2010). Job attitudes and employee engagement: A meta-analysis of construct redundancy. Presented at the 70th

annual meeting of the academy of management, Montreal, Canada.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction-job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological

Bulletin, 127, 376407.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692724.

Kraus, S. J. (1995). Attitudes and prediction of behavior: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 5875.

*Lepine, J. A., Erez, A., & Johnson, D. E. (2002). The nature and dimensionality of organizationalcitizenship behavior: A critical review and meta-analysis. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 87, 5265.

Lodahl, T. M., & Kejner, M. (1965). The definition and measurement of job involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 49, 2433.

Macey, W., & Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 1(1), 330.

Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin,

108, 171194.

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 2052.

Mitra, A., Jenkins, G., & Gupta, N. (1992). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between absence and turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(6), 879889.

Nahrgang, J. D., Morgeson, F. P., & Hofmann, D. A. (2011). Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 7194.

Newman, D. A., & Harrison, D. A. (2008). Been there, bottled that: Are state and behavioral work engagement new and useful construct wines?. Industrial and

Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 1, 3135.

Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2005). On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 175181.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879903.

Rich, B. L., LePine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617635.

Asterisk (*) denotes studies that were used to compute original meta-analytic estimates.

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

12

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

Riketta, M. (2002). Attitudinal organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 257266.

Riketta, M. (2008). The causal relation between job attitudes and performance: A meta-analysis of panel studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 472481.

Rogosa, D. (1980). A critique of cross-lagged correlation. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 245258.

Rosopa, P. J., & Stone-Romero, E. F. (2008). Problems with detecting assumed mediation using the hierarchical multiple regression strategy. Human Resource

Management Review, 18, 294310.

Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, 600619.

Salanova, M., Agut, S., & Peir, J. (2005). Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediation of

service climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 12171227.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2003). Test manual for the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Unpublished manuscript, Utrecht University, the Netherlands. Retrieved

from www.schaufeli.com.

*Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of

Organizational Behavior, 25, 293315.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. In A. B. Bakker (Ed.), Work engagement: A handbook

of essential theory and research (pp. 1024). New York, NY US: Psychology Press.

Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Bakker, A. B. (2006). Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde: On the differences between work engagement and workaholism. In R. Burke (Ed.), Work

hours and work addiction (pp. 194252). Northhampton, UK: Edward Elgar.

Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Van Rhenen, W. (2008). Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being?

Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 173203.

*Schaufeli, W., Bakker, A., & Van Rhenen, W. (2009). How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement and sickness absenteeism. Journal

of Organizational Behavior, 30(7), 893917.

Schaufeli, W., Salanova, M., Gonzlez-Rom, V., & Bakker, A. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 7192.

Sonnentag, S. (2003). Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. Journal of Applied Psychology,

88(3), 518528.

The Gallup Organization (19921999). Gallup workplace audit (copyright registration certificate TX-5 080 066). Washington, DC: U.S. Copyright Office.

Viswesvaran, C., & Ones, D. S. (1995). Theory testing: Combining psychometric meta-analysis and structural equations modeling. Personnel Psychology, 48(4),

865885.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 82, 183200.

Further Reading

*Agarwal, U. A., Datta, S., Blake-Beard, S., & Bhargava, S. (2012). Linking LMX, innovative work behaviour and turnover intentions: The mediating role of work engagement. The Career Development International, 17(3), 208230.

*Alfes, K., Shantz, A. D., Truss, C., & Soane, E. C. (2013). The link between perceived human resource management practices, engagement and employee behaviour: A

moderated mediation model. The International Journal Of Human Resource Management, 24(2), 330351.

*Bal, P. M., De Cooman, R., & Mol, S. T. (2013). Dynamics of psychological contracts with work engagement and turnover intention: The influence of organizational

tenure. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(1), 107122.

*Bhatnagar, J. (2012). Management of innovation: Role of psychological empowerment, work engagement and turnover intention in the Indian context. The

International Journal Of Human Resource Management, 23(5), 928951.

*Bickerton, G. R., Miner, M. H., Dowson, M., & Griffin, B. (2014). Incremental validity of spiritual resources in the job demands-resources model. Psychology of religion

and spirituality, advance online publication.

*Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., Sleebos, D. M., & Maduro, V. (2014). Uncovering the underlying relationship between transformational leaders and followers' task performance. Journal Of Personnel Psychology, 13(4), 194203.

*Britt, T. W., Mckibben, E. S., Greene-Shortridge, T. M., Odle-Dusseau, H. N., & Herleman, H. A. (2012). Self-engagement moderates the mediated relationship between

organizational constraints and organizational citizenship behaviors via rated leadership. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(8), 18301846.

*Brunetto, Y., Teo, S. T., Shacklock, K., & Farr-Wharton, R. (2012). Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, well-being and engagement: Explaining organisational commitment and turnover intentions in policing. Human Resource Management Journal, 22(4), 428441.

*Caesens, G., & Stinglhamber, F. (2014). The relationship between perceived organizational support and work engagement: The role of self-efficacy and its outcomes.

European Review Of Applied Psychology/Revue Europenne De Psychologie Applique, 64(5), 259267.

*Dane, E., & Brummel, B. J. (2014). Examining workplace mindfulness and its relations to job performance and turnover intention. Human Relations, 67(1),

105128.

*Fluegge, E. (2008). Who put the fun in functional? Fun at work and its effects on job performance. (Doctoral dissertation). (Retrieved from ABI/INFORM database. (UMI

No. 3322919)).

*Halbesleben, J. B., Wheeler, A. R., & Shanine, K. K. (2013). The moderating role of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the work engagementperformance process. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(2), 132143.

*Halbesleben, J., Harvey, J., & Bolino, M. C. (2009). Too engaged? A conservation of resources view of the relationship between work engagement and work interference

with family. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 14521465.

*Kane-Frieder, R. E., Hochwarter, W. A., & Ferris, G. R. (2014). Terms of engagement: Political boundaries of work engagementwork outcomes relationships. Human

Relations, 67(3), 357382.

*Karatepe, O. M. (2013). High-performance work practices and hotel employee performance: The mediation of work engagement. International Journal Of Hospitality

Management, 32, 132140.

*Karatepe, O. M., Beirami, E., Bouzari, M., & Safavi, H. P. (2014). Does work engagement mediate the effects of challenge stressors on job outcomes? Evidence from the

hotel industry. International Journal Of Hospitality Management, 36, 1422.

*Kinnunen, U., Feldt, T., & Mkikangas, A. (2008). Testing the effort-reward imbalance model among Finnish managers: The role of perceived organizational support.

Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(2), 114127.

*de Lange, A., De Witte, H., & Notelaers, G. (2008). Should I stay or should I go? Examining longitudinal relations among job resources and work engagement for stayers

versus movers. Work & Stress, 22(3), 201223.

*Li, X., Sanders, K., & Frenkel, S. (2012). How leadermember exchange, work engagement and HRM consistency explain Chinese luxury hotel employees' job performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(4), 10591066.

*Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., Mkikangas, A., & Ntti, J. (2005). Psychological consequences of fixed-term employment and perceived job insecurity among health care

staff. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 14(3), 209237.

*Prottas, D. (2013). Relationships among employee perception of their manager's behavioral integrity, moral distress, and employee attitudes and well-being. Journal

of Business Ethics, 113(1), 5160.

*Rich, B. L. (2006). Job engagement: Construct validation and relationships with job satisfaction, job involvement, and intrinsic motivation. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

*Salanova, M., Lorente, L., Chambel, M. J., & Martnez, I. M. (2011). Linking transformational leadership to nurses' extra-role performance: The mediating role of selfefficacy and work engagement. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(10), 22562266.

Please cite this article as: Mackay, M.M., et al., Investigating the incremental validity of employee engagement in the prediction of

employee effectiveness: A meta-analytic path an..., Human Resource Management Review (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.hrmr.2016.03.002

M.M. Mackay et al. / Human Resource Management Review xxx (2016) xxxxxx

13

*Shuck, B., Twyford, D., Reio, T. J., & Shuck, A. (2014). Human resource development practices and employee engagement: Examining the connection with employee

turnover intentions. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25(2), 239270.

*Simpson, M. R. (2009). Predictors of work engagement among medical-surgical registered nurses. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 31, 4465.

*Soane, E., Shantz, A., Alfes, K., Truss, C., Rees, C., & Gatenby, M. (2013). The association of meaningfulness, well-being, and engagement with absenteeism: A moderated mediation model. Human Resource Management, 52(3), 441456.

*Vogelgesang, G. R., Leroy, H., & Avolio, B. J. (2013). The mediating effects of leader integrity with transparency in communication and work engagement/performance.

The Leadership Quarterly, 24(3), 405413.