Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

8630 Lecture11

Hochgeladen von

Rajiv KharbandaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

8630 Lecture11

Hochgeladen von

Rajiv KharbandaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

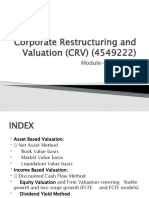

MHSA 8630 Health Care Financial Management

Capital Budgeting and Project Risk Assessment

I.

Principles of Capital Budgeting

**

Utilizing basic financial analysis principles such as discounted cash flow

analysis and cost of capital estimation, we now turn our attention to the

process by which organizational financial managers make decisions

regarding capital investments. In this context, capital investments are

regarded as fixed asset(s) having long useful lives that typically require

the organization to expend significant internal financial resources and/or

obtain external capital to finance such purchases.

**

The process by which organizations systematically evaluate alternative

capital investment projects and make decisions as to which should be

funded given limited capital resources is known as capital budgeting.

**

The capital budgeting process is of significant strategic importance to all

types of organizations, both FP and NFP, as appropriate long-term

investments in capital resources ensures, to the extent possible, that the

organization will remain viable in the future. Capital budgeting also

yields a shorter-term benefit in that it allows the organization to effectively

plan for capital expenditures ex ante, so that any required sources of

capital financing (debt, equity) can be obtained at the lowest possible cost

of capital to the organization.

**

Organizational failure to appropriately budget for its strategic capital

needs typically results in either (1) too much capital being deployed, thus

reducing organizational efficiency and cost competitiveness, or (2) too

little capital being deployed, thus resulting is lost strategic opportunities to

the organization and reduced long term growth.

**

Capital Project Classification: for purposes of capital budgeting analysis,

the following types of capital projects are typically included:

**

Discretionary replacement: capital projects intended to replace

existing equipment that is dated, but operational. The intention is

presumably to reduce equipment maintenance costs and/or

improve patient service. (mid-level management decision)

**

Existing product/service line expansion: capital projects intended

to increase service capacity in existing lines of business. (seniorlevel management decision)

**

New product/service line expansion: capital projects intended to

expand/move into new business lines (senior-level management).

**

Steps in the Capital Budgeting Process

(1)

Estimate Cash Flows: includes estimation of initial cash outflow(s)

or cost of financing the project as well as estimation of all

subsequent projected cash inflow(s) associated with the project,

including the terminal cash flow(s) associated with project

termination.

**

For purposes of capital budgeting analysis, only actual

incremental cash flows associated with the project should

be included and not various accounting measures such as

net income, which can present a misleading picture of

project profitability. Also, sunk costs (cash flows that have

already occurred prior to project initiation) should

generally be ignored regardless of association with project.

**

Though it is likely that project-related cash flows will occur

at sporadic intervals throughout the projects life, it is

generally assumed that all project-related flows occur once

per year, usually at the end of the year, for purposes of

analytical simplicity.

**

In terms of length of project life, most organizations will

specify a useful life of between five and ten years for most

capital investments, though some projects associated with

the addition of organizational capacity will likely be

analyzed over longer periods. Of note, for a given

corporate cost of capital, cash flows that occur far into the

future (20 years or greater) contribute little to the overall

capital budgeting analysis.

**

Miscellaneous methodological issues in the estimation of

cash flows include the following:

**

Opportunity cost estimation as it relates to the

project at hand is generally regarded as being

roughly accounted for in the organizations chosen

cost of capital/discount rate if (and only if) the

projects risk is comparable to the risk of the

organizations portfolio of projects as a whole.

**

Opportunity costs associated with other projectrelated resources (e.g. land, building space) should

be included within such analyses as well if the

project at hand makes collateral use of such

resources and imputes a cost as a result.

**

Miscellaneous methodological issues (continued):

**

To the extent that a project may effect other

projects, positively or negatively, such spillover

effects (in terms of incremental cash flows) should

be incorporated into the analysis.

**

In general, most projects will entail administrative

costs, such as shipping/delivery costs, setup and

training costs, maintenance/upkeep costs, etc. Such

costs are explicit and should obviously be

incorporated into the analysis as well.

**

If applicable, the cash flow-related effects of a

project on the organizations net working capital

(current assets less current liabilities) balance

should be included in the analysis as well,

especially if it is expected that a project will

dramatically reduce the NWC of the organization

(i.e. increase inventories, accounts receivables, etc.)

**

Inflation effects on organizational cash flow over

time should also be incorporated into such analyses.

Inflation should be accounted for with respect to

third party reimbursement, cost of goods, labor

costs, supply costs, etc. Depreciation expense

should NOT be adjusted for inflation.

**

In addition to the use of various objective criteria

(see below) to evaluate the worthiness of a specific

capital investment, organizational managers also

utilize a number of subjective criteria, including the

implied strategic value of a given project to the

organization, to assist in making such evaluations.

In general, the better the strategic fit between a

proposed capital investment and the organizations

strategic plan/mission/vision, the more likely that

such a capital investment should be made.

**

For investor-owned, for-profit organizations, the

effect of corporate taxation on project cash flows

must also be accounted for as part of the analysis, as

such taxes will affect organizational cash flows

during the life of the project as well as at project

termination, when the asset will presumably be sold

for salvage.

(2)

Discount Project Cash Flows: based on the derived estimate for

the corporate cost of capital/discount rate (adjusted if required to

reflect greater/lower project risk), all projected cash flows over the

projects useful life are discounted back to present value.

(3)

Evaluate Project Financial Impact: based on the result obtained

from discounting future cash flows, a formal evaluation of the

projected financial impact of the capital investment on the

organization can be conducted using one of several methods:

**

Net Present Value (NPV) Method -- NPV calculated as:

NPV = [CFi / (1 + r)n] - Initial Investment

>>

The decision rule with respect to using NPV to make

capital budgeting decisions is to only select those capital

investments that have a positive NPV, and reject those

whose NPV is negative.

>>

A positive NPV indicates that the capital project is

expected to provide a return on investment that is greater

than the corporate cost of capital, and thus will presumably

add to the value of the organizational enterprise as a result.

A negative NPV implies the opposite.

>>

The greater the NPV estimate, the greater the financial

return associated with the capital project. Among capital

projects with positive NPV estimates, those with the

highest NPV estimates are preferred, other things being

equal.

**

Project Implied Rate of Return (IRR) also known as

the internal rate of return, it is the rate of return that forces

the projects discounted cash flows to exactly equal the

initial investment (or NPV = 0).

>>

The decision rule with respect to using IRR to make capital

budgeting decisions is to only select those capital

investments where the IRR is greater than the corporate

cost of capital as specified. For all projects where IRR is

greater than the corporate cost of capital, the projected cash

flows are sufficient to provide a return that covers the

organizations cost of capital in addition to providing

returns to the organization and thus increasing its value.

**

>>

Either the NPV or IRR approaches to capital budgeting

analysis may be used in this case, and the results will be the

same regardless of which method used i.e. projects with

positive NPVs will be consistent with projects whose IRR

estimates exceed corporate cost of capital, and vice versa.

**

Breakeven Analysis Methods estimation of either the

period of time required (payback period/discounted

payback period) or the utilization volume required

(breakeven point) for the organization to recoup its initial

capital investment.

>>

Breakeven evaluation of capital investment alternatives

provide the organization with an estimate of the potential

profitability and risk associated with a given project. In

terms of roughly assessing the riskiness of a project,

breakeven methods are preferred to NPV and IRR, and are

often estimated concurrent with either/both measures of

project profitability.

>>

In general, the greater the breakeven utilization volume

required and/or the longer the payback/discounted payback

periods associated with a project, the riskier those projects

tend to be.

Capital Budget Decision Making

**

As mentioned previously, most of the decision-making as it relates

to capital budgeting resides with senior-level management within

the organization, especially as it relates to capital projects that have

significant strategic importance to the organization and/or involve

the commitment of significant organizational resources.

**

For capital projects that have similar useful lives in terms of their

investment time horizons, those projects that are preferred tend to

be those that (a) have significant strategic importance to the

organization, (b) are projected to be reasonably profitable as

measured by a positive NPV or an IRR that exceeds CCC, and

(c) entail a manageable/reasonable level of project risk as

measured by breakeven analysis.

**

Organizations will, from time to time, be faced with the evaluation

of mutually exclusive capital investment alternatives that have

significantly unequal useful lives in terms of investment time

horizon. Different methods must be applied to make such

comparisons fair.

**

**

Methods for Evaluating Projects with Unequal Useful Lives

**

Replacement Chain Analysis assumes that any given

project can be replicated after its termination. For example,

if a project has an estimated useful life of three years, this

method would assume that the same investment could be

made at the termination of the project at the end of year

three, with commensurate cash flows during years four,

five, and six similar to years one, two, and three. The

obvious, and most tenuous, assumption with this method is

that the project can be perfectly replicated. If such an

assumption isnt reasonable, this method shouldnt be used.

Also difficult to use when investment time horizons are

roughly similar (differ by a few years only).

**

Equivalent Annual Annuity (EAA) based on the

estimated NPV for each project, involves the estimation of

the implied annuity amount (PMT) for each project that

would yield the same estimated NPV. That project which is

associated with the higher EAA is the one that would be

preferred using this method because a higher EAA implies

a higher cash flow/higher NPV associated with a project of

whatever investment time horizon, assuming that such

investments could be easily replicated over time.

Capital Budget Decision Making Within NFP Organizations

**

Most of what has been discussed up to this point will apply

to both investor-owned and charitable organizations as it

relates to capital budget decision making.

**

NFP organizations differ substantively from FP entities due

largely to their charitable missions and the operational and

strategic constraints these missions impose.

**

One such constraint is particularly applicable in the capital

budgeting process, involving some degree of consideration

for the social value of a capital project in addition to

considering its financial/strategic value to the organization.

**

The Net Present Social Value Model was developed for the

purpose of evaluating capital investment alternatives in a

not-for-profit organizational setting, whereby both the net

present social value (NPSV) of a project is formally

considered along with the financial net present value

(NPV). (TNPV = NPV + NPSV)

**

**

In this model, it is assumed that the NFP entity will choose

to invest its limited resources in those capital projects that

provide the highest total net present value (TNPV). It is

further assumed that such entities will also not invest in any

capital projects where net present social value (NPSV) is

negative, regardless of the financial net present value

associated with such projects. Lastly, it is assumed that the

financial NPV associated with all of the NFPs capital

projects will be greater than or equal to zero, to ensure

long-run organizational viability.

**

The estimation of NPSV is somewhat conceptual, and

involves an attempt to assign a dollar value (cash flow

equivalent) to the social (un-priced) benefits associated

with a given capital project. Most often, such monetary

benefits are estimated based on an estimate of average

consumer willingness to pay for such benefits.

**

The discounting of future social benefits associated with a

capital project using the NPSV method requires the

specification of a social discount rate, or cost of capital,

much as in the investor-owned case. The social rate of

return or discount rate is even more conceptually

challenging to estimate than its investor-owned counterpart.

The most typical approach to estimating this rate of return

is to equate it to the returns that could be obtained by

investing those resources in an equivalent for-profit entity.

Evaluation of Capital Budgeting Financial Performance

**

Organizations that are committed to effective and efficient

capital budgeting processes will also have an interest in

evaluating the performance of their chosen capital

investment projects post hoc. Such retrospective forms of

evaluation are referred to as post audits.

**

Such audits involve the comparison of actual project results

(in terms of cash flows) with initial project projections,

explaining why differences exist between the two if

present, and analyzing potential changes to the projects

operations, including replacement and/or termination.

**

The primary purposes of the post capital budgeting audit

are to improve future forecasts, develop historical risk and

return data, improve organizational operations, and reduce

organizational losses associated with capital projects.

II.

Project Risk Measurement and Incorporation

**

Up to this point, it has been acknowledged that the most critical, and least

certain, part of the capital budgeting process involves the estimation of

future project cash flows for the purpose of estimating the profitability

associated with a capital project.

**

The presence of uncertainty, sometimes substantial, in the estimation of

future project cash flows introduces a degree of financial risk into the

capital budgeting process. The estimation and incorporation of project

risk into the capital budgeting process is necessary to account for those

proposed projects that have higher risk compared to other projects, as the

typical cost of capital estimate used to discount project cash flows only

applies to projects of average risk.

**

Measures of Project Risk

**

Stand-alone risk project-associated risk assuming the project is

held in isolation of any other projects, measured as the standard

deviation of the returns associated with the project.

**

Corporate risk project-associated risk assuming the project is

part of the business portfolio of projects, measured by the firms

corporate beta.

**

Market risk project-associated risk assuming the project is part of

a stockholders portfolio of projects/stocks, measured by the

market beta associated with the firms stock.

**

Among these three measures of project risk, it was argued

previously that corporate risk and market risk were more

appropriate measures because all businesses invest in multiple

projects and/or stocks, such that the risk associated with a single

project is best evaluated in light of a much larger, more well

diversified portfolio of projects/stocks.

**

Be that as it may, attempts to estimate project risk vis--vis a firms

corporate and/or market risk measures is fraught with

methodological as well as theoretical difficulties. As the vast

majority of projects that a firm may invest in are typically

significantly positively correlated with the returns of the business

as a whole/the returns of the companys stock (r = 0.3-0.6), it is

usually the case that estimates of a projects stand-alone risk,

which is much simpler to estimate, can be used to approximate

either/both the corporate risk and/or market risk associated with a

given project.

**

Estimation of Project Stand-Alone Risk

**

The three most common methods utilized to estimate a projects

stand-alone risk are sensitivity analysis, scenario analysis, and

Monte Carlo simulation techniques. In this course, we will only

discuss/examine the first two methods in any detail.

**

Sensitivity analysis methodological technique sometimes also

referred to as what if type of analysis, this technique shows how

specific changes in one or more project input variables (utilization,

charges, costs) affect the projects profitability as measured by

NPV, IRR, or payback.

**

>>

Typically, such analyses are conducted on several input

variables that are presumed to be most critical to the final

financial outcome of the project. Each variable is varied by

+/- 30% typically, holding all other variables constant, to

elucidate the relationship between the input variable and

the financial outcome of interest (NPV, IRR).

>>

Input variables that have more of an impact on the financial

outcome of interest are said to contribute the MOST to the

overall stand alone risk of the project. Graphically, such

relationships are identified as having steeper slopes when

graphed against the projects NPV

>>

The primary disadvantages to using sensitivity analysis for

this purpose are: (1) such analyses do not consider the

amount by which the input variable(s) could actually

change; (2) such analyses do not allow for the

consideration of any input variable interactions; (3) such

analyses provide no direct quantitative measure of standalone project risk.

Scenario analysis methodological technique that allows for the

examination of several possible project profitability outcomes typically by identifying a best case scenario, a worst case scenario,

and a most likely case scenario and estimating the projects

expected profitability as well as its stand-alone risk.

>>

A projects expected profitability under a variety of

possible scenarios is simply estimated by multiplying the

probability of each scenario by the financial outcome

associated with each scenario, much as was the process for

estimating the expected return associated with an

investment under conditions of uncertainty,

**

**

>>

A projects stand-alone risk is similarly estimated as before,

by calculating the standard deviation associated with the

expected financial outcome in the analysis.

>>

An alternative measure of stand-alone risk which adjusts

for the overall size of the project (and thus allows for more

applicable comparisons to other projects) is known as the

projects coefficient of variation (CV), which is simply the

projects standard deviation divided by the expected

financial outcome (NPV). In general, projects that have

large CV values have more stand-alone risk than those

projects that have smaller CV values.

Project Risk Incorporation into Capital Budgeting Decision Process

**

As mentioned previously, it is necessary to incorporate measures of

financial risk into the capital budgeting process for those projects

that are associated with higher levels of risk compared with the

firms average project.

**

As has been the case time and again in the financial analysis of risk

and return, the assumption of higher levels of financial risk require

greater financial returns to compensate investors for assuming

greater than average levels of risk. So, for projects that are more

risky, as well as less risky, than the businesss average project,

adjustments to the standard required rate of return

(corporate/divisional cost of capital) is necessary.

**

The most commonly utilized method for the purpose of risk

incorporation into capital budgeting is the risk-adjusted discount

rate method. In a nutshell, those projects that are riskier than the

firms average project should utilize a higher discount rate/cost of

capital to discount project cash flows. Those projects that are less

risky than the firms average project should utilize a lower discount

rate/cost of capital to discount project cash flows.

Capital Budgeting Applications for Non-Revenue Producing Projects

**

From time to time, organizations will make capital budgeting

decisions related to projects that do not produce any new sources

of revenue but are necessary for normal organizational operations.

(e.g. linen disposal service)

**

In the case of non-revenue producing projects, the goal of the

capital budgeting decision process is to identify those projects that

have the LOWEST net present cost to the organization.

**

As a typical example, an organization is faced with a build versus

buy choice related to a needed service, such as linen services for a

hospital. It is often the case that such alternatives will differ

substantially in the magnitude and timing of the costs to the

organization over a defined period.

**

If both projects are assumed to be of similar risk to the

organization, the costs associated with each are discounted at the

appropriate corporate/divisional cost of capital, and the alternative

with the lowest net present cost is typically preferred.

**

If one of the projects is deemed to be more risky than the other, for

whatever reason, such projects should utilize a different

corporate/divisional cost of capital to estimate NPC. Unlike NPV

methods, however, higher risk, non-revenue producing projects

should be discounted using a LOWER/SMALLER

corporate/divisional cost of capital than projects that are less risky.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- What is Capital BudgetingDokument4 SeitenWhat is Capital BudgetingShreya VermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital Budgeting at IOCLDokument12 SeitenCapital Budgeting at IOCLFadhal AbdullaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital Budgeting - THEORYDokument9 SeitenCapital Budgeting - THEORYAarti PandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fin. Analysis & Project FinancingDokument14 SeitenFin. Analysis & Project FinancingBethelhem100% (1)

- Sec-E: - Investment DecisionsDokument3 SeitenSec-E: - Investment Decisionsshreemant muniNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Lecture 1 & 2) - Introduction To Investment Appraisal MethodsDokument21 Seiten(Lecture 1 & 2) - Introduction To Investment Appraisal MethodsAjay Kumar Takiar100% (1)

- C.A IPCC Capital BudgetingDokument51 SeitenC.A IPCC Capital BudgetingAkash Gupta100% (4)

- (Lecture 1 & 2) - Introduction To Investment Appraisal Methods 2Dokument21 Seiten(Lecture 1 & 2) - Introduction To Investment Appraisal Methods 2Ajay Kumar TakiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital BudgetingDokument9 SeitenCapital BudgetingHarshitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definition of Capital BudgetingDokument6 SeitenDefinition of Capital Budgetingkaram deenNoch keine Bewertungen

- PPCM Unit -1 NotesDokument32 SeitenPPCM Unit -1 NotesAmit KumawatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital Budgeting Analysis and TechniquesDokument19 SeitenCapital Budgeting Analysis and TechniquesMELAT ROBELNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital Budgeting 2Dokument102 SeitenCapital Budgeting 2atharpimt100% (1)

- Chapter One: Capital Budgeting Decisions: 1.2. Classification of Projects Independent Verses Mutually Exclusive ProjectsDokument25 SeitenChapter One: Capital Budgeting Decisions: 1.2. Classification of Projects Independent Verses Mutually Exclusive ProjectsezanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CAPITAL BUDGETING_2Dokument45 SeitenCAPITAL BUDGETING_2chloemhae.ogayreNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1,,WEEK 1-2 - Introduction To Capital BudgetingDokument31 Seiten1,,WEEK 1-2 - Introduction To Capital BudgetingKelvin mwaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colbourne College Unit 14 Week 6Dokument29 SeitenColbourne College Unit 14 Week 6gulubhata41668Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Financial Sector of IndiaDokument11 SeitenThe Financial Sector of IndiaGunjan MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Part BDokument26 SeitenPart BpankajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital BudgetingDokument68 SeitenCapital Budgetingyatin rajput100% (1)

- Capital BudgetingDokument30 SeitenCapital BudgetingSakshi AgarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ba05 Group 4 - BSMT 1B PDFDokument31 SeitenBa05 Group 4 - BSMT 1B PDFMark David100% (1)

- 7 - Capital BudgetingDokument3 Seiten7 - Capital BudgetingChristian LimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 6 11 12Dokument15 SeitenChapter 6 11 12wubeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fin MGMTDokument51 SeitenFin MGMTdinugypsy123-1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Net Present Value: Capital Budgeting (Or Investment Appraisal) Is The Planning Process Used ToDokument4 SeitenNet Present Value: Capital Budgeting (Or Investment Appraisal) Is The Planning Process Used TorohitwinnerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of Capital BudgetingDokument3 SeitenPrinciples of Capital BudgetingSauhard AlungNoch keine Bewertungen

- C N .:-4 C B: Hapter O Apital UdgetingDokument8 SeitenC N .:-4 C B: Hapter O Apital UdgetingAmit KhopadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital Budgeting AnalysisDokument37 SeitenCapital Budgeting AnalysisEsha ThawalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital Budgeting TechniquesDokument11 SeitenCapital Budgeting Techniquesnaqibrehman59Noch keine Bewertungen

- Long Term Investment Decision Making ("Capital Budgeting" An Approach)Dokument47 SeitenLong Term Investment Decision Making ("Capital Budgeting" An Approach)samadhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 22 Capital Rationing and Criteria For Investment AnalysisDokument10 Seiten22 Capital Rationing and Criteria For Investment AnalysisManishKumarRoasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Key Steps in Project AppraisalDokument4 SeitenKey Steps in Project Appraisaljaydeep5008Noch keine Bewertungen

- Capital Budgeting Investment Decisions: GuideDokument62 SeitenCapital Budgeting Investment Decisions: Guidetanya100% (1)

- Info. L Chapter 5 Investment Decision For Special ClassDokument13 SeitenInfo. L Chapter 5 Investment Decision For Special ClassGizaw BelayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Estimation of Project Cash FlowsDokument26 SeitenEstimation of Project Cash Flowssupreet2912Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture Note Capital Budgeting Part 1Dokument14 SeitenLecture Note Capital Budgeting Part 1Kamrul HasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital BudgetingDokument62 SeitenCapital BudgetingtanyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Long-term investment analysisDokument13 SeitenLong-term investment analysissamuel kebedeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital expenditure and revenue expenditure explainedDokument3 SeitenCapital expenditure and revenue expenditure explainedchautsi preciousNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital Budgeting: Exclusive ProjectsDokument6 SeitenCapital Budgeting: Exclusive ProjectsMethon BaskNoch keine Bewertungen

- Madras University MBA Managerial Economics PMBSE NotesDokument11 SeitenMadras University MBA Managerial Economics PMBSE NotesCircut100% (1)

- Capitalbudgeting 1227282768304644 8Dokument27 SeitenCapitalbudgeting 1227282768304644 8Sumi LatheefNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basics of AppraisalsDokument20 SeitenBasics of AppraisalssymenNoch keine Bewertungen

- L1R32 Annotated CalculatorDokument33 SeitenL1R32 Annotated CalculatorAlex PaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurship (Module 6)Dokument17 SeitenEntrepreneurship (Module 6)prasenjit00750% (4)

- CAPITAL BUDGETING OR INVESMENTDokument6 SeitenCAPITAL BUDGETING OR INVESMENTtkt ecNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Modelling and ValuationDokument5 SeitenFinancial Modelling and Valuationibshyd1100% (1)

- Module 2 - Analysis and Techniques of Capital BudgetingDokument42 SeitenModule 2 - Analysis and Techniques of Capital Budgetinghats300972Noch keine Bewertungen

- 54 Capital BudgetingDokument4 Seiten54 Capital BudgetingCA Gourav JashnaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital Budgeting Decision Is An Important, Crucial and Critical Business Decision Due ToDokument7 SeitenCapital Budgeting Decision Is An Important, Crucial and Critical Business Decision Due ToGaganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap 4 CDokument33 SeitenChap 4 CHiwot AderaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analyze Investment Projects with NPVDokument16 SeitenAnalyze Investment Projects with NPVAbdul Fattaah Bakhsh 1837065Noch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Capital BudgetingDokument42 SeitenBasic Capital BudgetingMay Abia100% (2)

- MAS 10 Capital BudgetingDokument9 SeitenMAS 10 Capital BudgetingZEEKIRA100% (1)

- Case StudyDokument10 SeitenCase StudyAmit Verma100% (1)

- Chapter-Six 6.preparation of Operating Budgets: Financial AccountingDokument6 SeitenChapter-Six 6.preparation of Operating Budgets: Financial AccountingWendosen H FitabasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ch-7 Approaches of Business ValuationDokument46 SeitenCh-7 Approaches of Business ValuationManan SuchakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Investments Profitability, Time Value & Risk Analysis: Guidelines for Individuals and CorporationsVon EverandInvestments Profitability, Time Value & Risk Analysis: Guidelines for Individuals and CorporationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decoding DCF: A Beginner's Guide to Discounted Cash Flow AnalysisVon EverandDecoding DCF: A Beginner's Guide to Discounted Cash Flow AnalysisNoch keine Bewertungen

- AdmitCard Candidate PDFDokument2 SeitenAdmitCard Candidate PDFRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accounta A 2016 2nd SemDokument16 SeitenAccounta A 2016 2nd SemRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Haryana Board School Registration 2019-20 SuccessDokument1 SeiteHaryana Board School Registration 2019-20 SuccessRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HBSE 11th Business Studies 2018 PaperDokument7 SeitenHBSE 11th Business Studies 2018 PaperRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2015 Accountancy Question PaperDokument4 Seiten2015 Accountancy Question PaperJoginder SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brand Awareness and Consumer Preference With Reference To FMCG Sector inDokument11 SeitenBrand Awareness and Consumer Preference With Reference To FMCG Sector inRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabus 11th Accountancy 16-04-2018Dokument2 SeitenSyllabus 11th Accountancy 16-04-2018Rajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GJHDokument1 SeiteGJHRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TuitionDokument2 SeitenTuitionRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HBSE 11th Business Studies 2018 PaperDokument7 SeitenHBSE 11th Business Studies 2018 PaperRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.3, Ravi C.SDokument11 Seiten1.3, Ravi C.SManish JangidNoch keine Bewertungen

- CompanyDokument2 SeitenCompanyRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factor and Product FormulasDokument1 SeiteFactor and Product FormulasrahulgngwlNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2008 Accountancy Question PaperDokument4 Seiten2008 Accountancy Question PaperRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Detail of Marks of Class - Name:-Father's Name Mother's NameDokument1 SeiteDetail of Marks of Class - Name:-Father's Name Mother's NameRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expirement No 2Dokument5 SeitenExpirement No 2Rajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cash Flow AnalysisDokument38 SeitenCash Flow AnalysisDragan100% (4)

- CRM in Banking ContextDokument9 SeitenCRM in Banking Contextankush12_mohodNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Influence of QualityDokument4 SeitenThe Influence of QualityRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer PreviewDokument1 SeiteCustomer PreviewRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- M GrapsDokument4 SeitenM GrapsRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job PprofileDokument2 SeitenJob PprofileRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Influence of QualityDokument4 SeitenThe Influence of QualityRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expirement No 1Dokument4 SeitenExpirement No 1Rajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lat LongDokument126 SeitenLat LongRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job PprofileDokument2 SeitenJob PprofileRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opininon of CustomerDokument1 SeiteOpininon of CustomerRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employee Job Satisfaction at IFIC BankDokument77 SeitenEmployee Job Satisfaction at IFIC BankRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job PprofileDokument2 SeitenJob PprofileRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opininon of CustomerDokument1 SeiteOpininon of CustomerRajiv KharbandaNoch keine Bewertungen