Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Beachgoers's Perceptions of Sansy Beach Conditions. Lucrezi and Van Der Walt 2015

Hochgeladen von

Iuri AmazonasCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Beachgoers's Perceptions of Sansy Beach Conditions. Lucrezi and Van Der Walt 2015

Hochgeladen von

Iuri AmazonasCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283153693

Beachgoers perceptions of sandy beach

conditions: demographic and attitudinal

influences, and the implications for beach

ecosystem management

Article in Journal of Coastal Conservation October 2015

DOI: 10.1007/s11852-015-0419-3

CITATIONS

READS

76

2 authors, including:

Serena Lucrezi

North West University South Africa

24 PUBLICATIONS 247 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

GreenBubbles View project

All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate,

letting you access and read them immediately.

Available from: Serena Lucrezi

Retrieved on: 07 October 2016

Beachgoers perceptions of sandy beach

conditions: demographic and attitudinal

influences, and the implications for beach

ecosystem management

Serena Lucrezi & Marthienus Frederik

van der Walt

Journal of Coastal Conservation

Planning and Management

ISSN 1400-0350

J Coast Conserv

DOI 10.1007/s11852-015-0419-3

1 23

Your article is protected by copyright and all

rights are held exclusively by Springer Science

+Business Media Dordrecht. This e-offprint

is for personal use only and shall not be selfarchived in electronic repositories. If you wish

to self-archive your article, please use the

accepted manuscript version for posting on

your own website. You may further deposit

the accepted manuscript version in any

repository, provided it is only made publicly

available 12 months after official publication

or later and provided acknowledgement is

given to the original source of publication

and a link is inserted to the published article

on Springer's website. The link must be

accompanied by the following text: "The final

publication is available at link.springer.com.

1 23

Author's personal copy

J Coast Conserv

DOI 10.1007/s11852-015-0419-3

Beachgoers perceptions of sandy beach conditions:

demographic and attitudinal influences, and the implications

for beach ecosystem management

Serena Lucrezi 1 & Marthienus Frederik van der Walt 2

Received: 22 July 2015 / Revised: 17 September 2015 / Accepted: 14 October 2015

# Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2015

Abstract Sandy beaches represent typical venues for recreation and tourism worldwide, as well as part of the lifestyle and

identity of coastal communities. Their overexploitation,

however, threatens their survival. Especially in urban

areas, beach management requires balancing needs by different users and obligations to protect beach functions,

including conservation. In light of this, research about

the human dimension of beach ecosystems has been advanced as a way to assist planning and decision making in

beach management. This study assessed beachgoers' perceptions of sandy beach conditions in South Africa, by

means of a questionnaire survey. The effects of demographic profile, travelling habits, motivations to visit, and

recreational preferences on beachgoers' perceptions of

beach conditions were tested. Beachgoers shared a general

concern for the wellbeing of sandy beaches, with particular reference to the state of biodiversity and conservation.

They also gave great importance to the values underlying

beach ecosystems. Three motivations to visit groups and

four recreational preferences types were identified. Demography, travelling habits, motivations to visit, and recreational

preferences all influenced perceptions of beach conditions.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article

(doi:10.1007/s11852-015-0419-3) contains supplementary material,

which is available to authorized users.

* Serena Lucrezi

23952997@nwu.ac.za

1

TREES Tourism Research in Economic Environs and Society,

North-West University, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa

School of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts, North-West University,

Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa

The results from this study were used to draw management

recommendations, with particular attention towards the

promotion of conservation while also maintaining the

recreational quality of urban sandy beaches. The results

also highlighted the relevance of considering users' views as a

tool in decision-making processes in Integrated Coastal Zone

Management.

Keywords Sandy beach . Perception . Beachgoer . Value .

Conservation . Management

Introduction

Sandy beach ecosystems provide invaluable services to humankind. Their functions have been exploited through history,

with significant anthropogenic effects (Schlacher et al. 2008;

Defeo et al. 2009). One of the most discussed uses of sandy

beaches is for recreational and tourism purposes. Beaches

worldwide have become large-scale recreational and tourism

areas, mostly due to economic development and settlements

along coastlines (Defeo et al. 2009; McLachlan et al. 2013).

Aside from being a desired destination for sand, sun, and sea

seekers, sandy beaches also represent part of the lifestyle and

identity of coastal communities. This results in a mix of preferences, uses, and attitudes towards beaches, which need to be

managed in accordance with principles of Integrated Coastal

Zone Management (ICZM) (Villares et al. 2006; Maguire

et al. 2011). The task is difficult, considering that human pressures tend to conflict with conservation obligations, all in the

backdrop of impinging global climatic changes and consequent rises in sea level (McLachlan et al. 2013).

Especially in urban areas, the traditional management of

sandy beaches has been prescribing reactive and top-down

Author's personal copy

Lucrezi S., van der Walt M.F.

approaches, primarily focused on maintaining the physical

environment, with little regard for the opinion of various

stakeholder groups (James 2000; Villares et al. 2006). Even

when recreational and tourism services are prioritised,

this is done without consideration of the users' point

of view (Roca and Villares 2008; Lozoya et al. 2014).

With such approaches being unsustainable, proactive

ways to tackle the dynamic interaction between physical, ecological, social, and economic dimensions of

beaches have been advocated over the last few years.

Among the various recommendations made by the scientific community, is that research be done about the

human dimensions of beach ecosystems and environments. This type of research underpins the ICZM approach and is intended to highlight the diversity of

values, images, principles, cultures, and interpretations

defining users and their rapport with beach ecosystems

(Maguire et al. 2011; Voyer et al. 2015). The information

collected can assist and enhance planning and decision

making, therefore it should constitute an integral part of

beach management (Villares et al. 2006; Roca and Villares

2008; Roca et al. 2009).

South Africa is a developing country with a significantly

long coastline, almost half of which is characterised by sandy

beaches (Harris et al. 2011). The dry beach and surf zones are

relatively protected, thanks to a series of legislations such as a

general ban on beach driving, and the establishment of MPAs

(Marine Protected Areas) covering some 23 % of the shoreline

(Harris 2012; Mead et al. 2013). Nonetheless, sandy beaches

in the country have remained subject to development and to

tourism growth, leading to continuing conflicts between use

and ecosystem conservation which ultimately affect both of

these negatively (Mead et al. 2013; Colenbrander et al. 2015;

Harris et al. 2015). These conflicts can be aggravated by

poor decision making and a lack of a solid decision-support

framework in coastal policy, with the risk of causing further

ecosystem degradation and loss of appeal (Celliers et al.

2015). With this background in mind, user perception studies

in the country are still rare (e.g. de Ruyck et al. 1995; Lucrezi

et al. 2015) yet they are needed to stimulate and assist management decisions for beach ecosystems.

This study set out to assess beachgoers' perceptions of

sandy beach conditions in South Africa, using a number of

urban recreational beaches as case studies. Given that perceptions can vary across different user groups (Wolch and Zhang

2004; Roca and Villares 2008; Roca et al. 2009), this study

also tested the effects of demographic profile, travelling

habits, motivations to visit, and recreational preferences, on

beachgoers' perceptions of beach conditions. The ultimate

goal was to use the information gathered to draw management

recommendations, with particular attention being paid to the

promotion of conservation while also maintaining the recreational quality of urban sandy beaches.

Methods

Study area

This study was carried out in the Western Cape Province of

South Africa, in the municipalities of the City of Cape Town

and Mossel Bay (Fig. 1). In Cape Town, the beaches of Muizenberg (34630.00S-182814.43E), Camps Bay (3357

8.48S-182237.56E), Clifton 4th (335627.57S- 1822

30.05E), and Clifton 1st-3rd (335621.34S- 182236.36

E) were chosen. In Mossel Bay, the beaches of Santos (3410

41.45S-22816.17E), Diaz (34933.78S-22637.65E),

and Hartenbos (34737.87S-2277.16E) were selected.

All the beaches are exposed to the ocean (Indian and Atlantic),

are microtidal, and characterised by a Mediterranean climate.

While Muizenberg, Hartenbos, and Diaz are up to several km

long, Clifton, Camps Bay, and Santos are embayed beaches

not exceeding 1 km in length.

The beaches of Cape Town are located within the

boundaries of the Table Mountain National Park MPA.

These urban beaches bask in the popularity of the urban

centre of Cape Town, attracting domestic and international

visitors all-year-round (Ballance et al. 2000). Muizenberg

is a popular surfing beach, where a shark conservationspotting programme is being implemented, and regularly

receives the Blue Flag award for education, water quality,

management, and safety (Kock et al. 2012; Blue Flag

South Africa 2014). Camps Bay and Clifton are defined

as resorts for the super rich, with real estate prices up to

ZAR 120 million (USD almost 12.5 million). In 2014, the

beaches were listed among the best travel and beach destinations in the world (Tripadvisor 2014). Camps Bay and

Clifton 4th regularly receive the Blue Flag, although the

water quality at these beaches has been compromised due

to pollution (Weimann 2014).

Mossel Bay has a series of urban beaches primarily subject

to domestic or second-home tourism (Saayman et al. 2009).

The area has historical and palaeoanthropological value, as the

place where Bartholomeu Dias first discovered the southern

tip of Africa, and where the first human fisher settlements

were established on the continent. The beaches are famous

locations from where the migration of whales can be observed

(Davie 2008). Santos is a Blue Flag beach and the only northfacing beach in South Africa; its gentle surf renders it a desirable destination for families with children. Diaz is a base for

surfing and diving learners. Hartenbos is a Blue Flag beach

and an important congregating site for great white sharks

(Klimley and Ainley 1998).

Beach survey

The research followed a quantitative, descriptive and nonexperimental design, employing a structured questionnaire

Author's personal copy

Beachgoers perceptions of sandy beach conditions: demographic and attitudinal influences, and the...

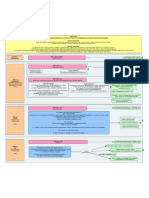

Fig. 1 Study area, Western Cape, South Africa. The beaches sampled were Clifton (a), Camps Bay (b), and Muizenberg (c) in Cape Town; Santos (d),

Hartenbos (e), and Diaz (f) in Mossel Bay

survey administered to people at the beaches under investigation (please refer to Appendix 1). The questionnaire was developed from previous studies such as those conducted by de

Ruyck et al. (1995); Cendrero and Fischer (1997); Leatherman

(1997); Morgan (1999); Pereira et al. (2003); Cervantes et al.

(2008); Ariza et al. (2010); and Maguire et al. (2011).

The questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first included demographic questions, specifically gender, age, marital status, origin, visitor type, education, occupation, and income. Participants were asked what accommodation they

were using; how many nights they were staying (overnight

visitors); how frequently they visited the beach annually;

who accompanied them; and their preferred time to visit the

beach. The second section asked about the importance of various motivations to visit (30 items) and recreational activities

(21 items) during beach visits. The level of importance was

accorded in terms of a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from

1 (extremely low) to 7 (extremely high). The last section

encompassed perceptions of beach conditions. Using a

seven-point Likert scale of condition, ranging from 1 (extremely bad) to 7 (excellent), beachgoers were invited to evaluate the state of the characteristics of the beach including

physical (18 items); bio-environmental (33 items); infrastructure and services (35 items); socioeconomic, cultural, and

religious-spiritual (eight items); and conservation (14 items).

Beachgoers were asked to rate the importance of both inherent

and utilitarian values (six items) associated with the beach,

using a seven point Likert scale of importance.

In total, 500 questionnaires were handed out to people at

the beach during school holidays in 2014 (2729 March in

Cape Town and 1819 April in Mossel Bay). Each beach was

sampled by two fieldworkers per day between 09:00 and

15:00. The data were collected via probability sampling, following a systematic approach (Maree and Pietersen 2007).

Every second person on the beach was reached by the

fieldworkers, either on a shore-parallel or shore-normal manner (Tudor and Williams 2006), and invited to participate in

the survey. Fieldworkers were instructed to indicate the aim of

the survey to the beachgoers. The participants took no longer

than 15 min to fill in the survey (Williams and Micallef 2009).

A total of 496 questionnaires were completed and returned,

yielding a success rate of 99 %. The number of questionnaires

returned per beach varied from 46 (Clifton 1st-3rd) to 91

(Muizenberg). Given that a sample size of 400 yields a standard error of 5 % (Williams and Micallef 2009), the final

number of surveys returned was considered appropriate for

data analysis.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics, breakdown statistics, and frequency tables were used to draw the participants' profile, and to capture

Author's personal copy

Lucrezi S., van der Walt M.F.

average scores and response frequencies for each question.

Two exploratory techniques were used on motivations, recreational preferences, and perceptions of beach conditions. The

first technique is the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), normally employed to reduce the size of a dataset by identifying

relationships between questionnaire items, and extracting latent factors (determined by eigen values and factor loadings as

cut-off criteria, and then calculated as factor scores) underlying the items (Stevens 2012). The second technique is

characterised by reliability tests, which ascertain that the factor scores derived from EFA have internal consistency (represented by the Cronbachs value) (Nunnally and Bernstein

1994). A single EFA was performed for each set of variables in

the questionnaire, thus pooling the information coming from

different beaches. This decision was mainly based on common recommendations by the literature concerning acceptable

sample sizes for EFA (Comrey 1973; Comrey and Lee 1992;

Hair et al. 1995; Tabachnick and Fidell 2007). It is true that

minimum sample sizes for EFA can be small (<50) if data are

well conditioned (i.e. high factor loadings, low number of

factors, and high number of variables) (MacCallum et al.

1999; de Winter et al. 2009). In this study, however, minimum

sample sizes per beach for satisfactory factor recovery were

generally greater than 50 (calculated according to de Winter

et al. 2009), and the actual sample size on each beach ranged

between 46 and 91, thus not allowing separate factor analyses

to be performed for each beach.

Normality tests were performed for continuous variables,

while there were no cases where scores were greater than 90 %

within a category for categorical variables. Therefore, the variability of demographic characteristics and travelling habits

across beaches was assessed through a nested ANOVA, testing the effect of municipality and beach nested in municipality. The influence of demography and travelling habits on

peoples responses, that is, all reliable factors extracted from

EFA, were investigated through one-way ANOVA. Continuous independent variables such as age were categorised for the

purpose of this analysis. Demographic characteristics and

travelling habits which were significantly influential on peoples responses were included as covariates in a nested

ANCOVA, contrasting responses (i.e. all reliable factors extracted from EFA) across municipalities and beaches nested in

municipalities.

For each ANOVA and ANCOVA, partial eta squared (2p)

was reported as the effect size based on standardised differences between the means (Cohen 1973). This type of effect

size is normally recommended in cases where independent

variables have more than two levels, and describes the proportion of variability accounted for by each independent variable

(Fritz and Morris 2012). Significant interactions were investigated through Fishers least significant difference (LSD) posthoc tests. The variation in peoples perceptions of beach conditions across motivations to visit and recreational preferences

for the beaches studied was explored through canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) (Ter Braak 1986). This is a multivariate technique that investigates relationships between sets

of categorical variables. The result of CCA is the ordination of

the principal dimensions of the dependent variables in a space

constrained by the explanatory variables (Greenacre 2010).

All data were analysed with the software Statsoft Statistica

(Version 12, 2013) and PAST (Version 2.17, Hammer et al.

2001).

Results

The participants in the survey comprised 60 % female and

40 % male, from 11 to 73 years old. The average age was 34

and similar across all beaches, except for Camps Bay

(27 years) and Muizenberg (40 years) (Table 1). Most of the

participants were either single (39 %) or married (35 %) nationals (77 %) from the Western Cape (57 %). While there

were almost no foreigners in Muizenberg and Mossel Bay,

Camps Bay and Clifton hosted several (35 %-58 %), mostly

from northern Europe (Table 1). Locals and day visitors were

dominant in Muizenberg, while the rest of the beaches were

visited by many overnight stayers (41 %-75 %) (Table 1).

About half of the participants possessed a degree or diploma,

with some having attained postgraduate qualifications. Education level was higher in Cape Town than in Mossel Bay

(Table 1). The participants were employed (60 %) or students

(25 %), earning an average of ZAR 260,000 per annum (USD

23,700); people in Clifton 1st-3rd earned the highest income

(Table 1). The type of accommodation used was primarily

owned in Muizenberg and Mossel Bay, and rented at the other

beaches. Cape Town was visited for longer periods (29 nights)

compared with Mossel Bay (six nights) (Table 1). However,

visits to Mossel Bay were more frequent (40 visits per year)

compared with those to Cape Town (18 visits per year)

(Table 1). Most of the participants were travelling with

friends, family, and spouses. The favourite period to visit the

beach was weekdays and weekends in Clifton and Camps

Bay; weekends and holidays in Muizenberg and Mossel Bay.

Descriptive and exploratory statistics for all the factors extracted from EFA (i.e. motivations to visit, recreational preferences, and perceptions of beach conditions) are outlined in

the supplementary material (Appendixs 2 to 7). The most

important reasons for visiting the beach were relaxation, escape, and socialisation. Scenery, safety, and lifestyle also stimulated visitation. People were less likely to visit the beach for

work or convenience reasons. The EFA extracted three reliable motivation factors. The first factor, middle aged, described people enjoying quiet tourism in contact with nature,

but also reliant on supporting facilities and services on the

beach. The second factor, socialising bather, described people

seeking relaxation and socialisation, but were also bathers or

Author's personal copy

Beachgoers perceptions of sandy beach conditions: demographic and attitudinal influences, and the...

Table 1 Significant effects of municipality and beach (nested in

municipality) on beachgoers demographic profile and travelling habits

(nested ANOVA); and on motivations to visit, recreational preferences,

and perceptions of beach conditions (nested ANCOVA). Partial eta

Treatment

Age

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Visitor type

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Income

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Length of stay

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Middle aged

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Water dependent

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Beach-sand

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

df

MS

p2

1

54.2

0.34

0.001

5

1297.7

8.25

***

0.09

426

157.4

Camps Bay < all other beaches p < 0.05

Muizenberg > all other beaches at p < 0.05

squared (2p) is reported as the effect size based on standardised

differences between the means. Significant interactions were

investigated through Fishers least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc

tests

Treatment

Nationality

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Education

1

0.05

0.08

0.001

Municipality

5

7.47

10.93

***

0.10

Beach (municipality)

482

0.68

Error

Muizenberg, Santos, and Diaz hosted more locals and Fishers LSD

day visitors compared with other beaches at

p < 0.05

1

12.11

2.42

0.001

5

12.80

2.56

*

0.03

388

5.01

Clifton 1st-3rd > all other beaches at p < 0.05

1

10,066.39

12.03

***

0.05

5

1192.47

1.43

0.03

454

836.79

Muizenberg and Mossel Bay < all other beaches at

p < 0.001

1

14.24

6.85

**

0.02

5

3.40

1.64

0.02

411

2.08

Cape Town > Mossel Bay at p < 0.05

Clifton 1st-3rd < all other beaches at p < 0.01

1

1.80

1.16

5

7.29

4.71

***

268

1.55

Clifton 1st-3rd < all other beaches at p < 0.05

1

7.11

10.91

**

0.02

5

3.88

5.94

***

0.06

449

0.65

Camps Bay, Clifton, and Hartenbos < all other

beaches at p < 0.05

Pollution-degradation

Municipality

1

Beach (municipality) 5

20.97

2.21

20.08

2.12

***

0.04

0.02

Occupation

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Annual visitation

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Habitual

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Nonintrusive

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Hazards

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

df

MS

p2

1

11.19

89.07

***

0.16

5

2.05

16.31

***

0.15

474

0.13

Cape Town hosted more overseas visitors than

Mossel Bay at p < 0.001

Clifton and Camps Bay hosted more overseas

visitors than all other beaches at p < 0.01

1

14.76

26.55

***

0.06

5

1.76

3.16

**

0.03

454

0.56

Cape Town > Mossel Bay at p < 0.001

Clifton 1st-3rd > all other beaches at p < 0.05

Muizenberg < Camps Bay and Clifton 1st-3rd at

p < 0.05

1

1.11

2.46

0.01

5

2.78

6.17

***

0.06

472

0.45

Camps Bay hosted more students than all other

beaches at p < 0.05

1

69,078

22.38

***

0.05

5

25,440.4

8.24

***

0.09

397

3086.5

Mossel Bay > Cape Town at p < 0.001

Santos, Diaz, and Muizenberg > all other

beaches at p < 0.05

1

13.08

5.69

**

0.02

5

2.89

1.25

0.02

330

2.30

Mossel Bay > Cape Town at p < 0.01

Camps Bay < all other beaches at p < 0.05

1

7.31

4.96

*

0.02

5

3

2.04

0.04

269

1.48

Clifton 1st-3rd < all other beaches at p < 0.05

1

1.17

1.42

0.001

5

3.07

3.71

**

0.04

396

0.83

Camps Bay, Clifton 1st-3rd, Hartenbos, and

Muizenberg < all other beaches at p < 0.05

Wildlife-landscape

Municipality

1

Beach (municipality) 5

7.42

7.78

5.58

5.85

*

***

0.01

0.06

Author's personal copy

Lucrezi S., van der Walt M.F.

Table 1 (continued)

MS

p2

Treatment

df

Error

Fishers LSD

Crowding-pests

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

439

1.04

Santos and Diaz > all other beaches at p < 0.01

1

3.02

2.55

0.01

5

3.06

2.59

*

0.03

428

1.18

Diaz > all other beaches at p < 0.05

Muizenberg < all other beaches at p < 0.05

df

Error

Fishers LSD

Safety-management

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

425

1.33

Muizenberg < all other beaches at p < 0.05

Hygiene-parking

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

1

10.01

8.04

**

0.02

5

3.60

2.89

*

0.03

418

1.24

Clifton 1st-3rd < all other beaches at p < 0.05

Area for activities

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

Culture

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

1

7.49

4.26

*

0.01

5

7.29

4.15

**

0.05

378

1.76

Clifton 1st-3rd < all other beaches at p < 0.05

Value

Municipality

Beach (municipality)

Error

Fishers LSD

MS

p2

Treatment

1

0.36

0.29

0.001

5

5.87

4.61

***

0.05

418

1.27

Clifton 1st-3rd and Diaz < all other beaches at

p < 0.05

1

6.37

4.71

*

0.01

5

8.65

6.40

***

0.07

415

1.35

Hartenbos > all other beaches at p < 0.05

Clifton < all other beaches at p < 0.05

1

2.03

1.90

0.01

5

4.04

3.77

**

0.06

294

1.07

Camps Bay and Clifton 1st-3rd < all other

beaches at p < 0.05

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

surfers reliant on good weather and safety. The third factor,

habitual, described people familiar with the beach, and visiting it as part of their lifestyle and wellbeing.

The greatest recreational preference was for relaxation and

socialisation. Intrusive recreation (four-wheel driving, horseriding, camping, and fishing) received the lowest interest. The

EFA on recreational preferences extracted four reliable factors. The first factor, intrusive-high cost, described people

enjoying motorised recreation (both in the water and on the

beach), shopping, and activities like fishing. The second factor, beach dependent, described people enjoying relaxation,

socialisation, and beach sports. The third factor, water

dependent, described people enjoying bathing, swimming,

surfing, or similar. The last factor, nonintrusive, described

people enjoying wildlife and scenery observation, photography, walking, and picnics.

The EFA on perceptions of beach conditions extracted

three reliable factors for physical characteristics, namely

beach-sand, hazards, and bathing area-water. Perceptions

of bio-environmental characteristics included the factors

pollution-degradation, wildlife-landscape, and crowdingpests. Perceptions of infrastructure and services included the

factors safety-management, outlets-accommodation, hygieneparking, and area for activities. Perceptions of socioeconomic,

cultural, and religious-spiritual characteristics formed the factors socioeconomics and culture. Perceptions of conservation

formed a single reliable factor, as did perceptions of values

associated with the beach. Perceptions of beach conditions

were generally positive, although some factors received higher

ratings than others. People accorded extreme importance to the

values of the beach, generational equity in primis. They allocated good ratings to physical properties like beach and sand

quality, the scenery and the lack of oil pollution, accommodation and walking areas, and beach popularity. They were more

critical of the condition of infrastructure and services such as

recycling and children facilities. They also assigned lower ratings to cultural aspects, natural aspects including wildlife

abundance and diversity, and conservation.

Motivations to visit, recreational preferences, and perceptions of beach conditions varied significantly according to

demography and travelling habits (Table 2). Habitual tourists

were likely to be South African local residents visiting the

beach more frequently, and interested in more active than

passive recreation compared with domestic and international

visitors. The latter group, especially if visiting for longer periods, tended to be more critical of beach and water quality, the

state of pollution and degradation, retail, accommodation, and

cultural features. Besides being a priority to visitors, relaxation and socialisation were particularly favoured by females.

Similarly, age, education, and a better income decreased expectations for intrusive-high cost and more active recreation.

The values of beaches were strongly supported by females,

Author's personal copy

Beachgoers perceptions of sandy beach conditions: demographic and attitudinal influences, and the...

Table 2 Significant effects of demography and travelling habits (one-way

ANOVA) on beachgoers' motivations to visit, recreational preferences, and

perceptions of beach conditions. Partial eta squared (2p) is reported as the

effect size based on standardised differences between the means. Significant

interactions were investigated through Fishers least significant difference

(LSD) post-hoc tests where appropriate

p2

Treatment

df

MS

9.09

***

0.04

Nationality

Error

1

403

16.38

2.44

p2

6.70

**

0.02

***

0.03

Treatment

df

MS

Tourist type

Error

2

407

21.69

2.39

Fishers LSD

Local residents > day and overnight visitors at p < 0.01 Fishers LSD

Intrusive-high cost

NA

Nationality

22.21

Nationality

23.73

Error

Fishers LSD

393

NA

2.26

Error

Fishers LSD

401

NA

1.77

Nationality

Nonintrusive

9.73

6.16

Nationality

Outlets-accommodation

5.76

5.29

*

Error

398

1.58

Error

412

1.09

Fishers LSD

NA

Fishers LSD

NA

Nationality

Error

Fishers LSD

1

384

NA

Habitual

Habitual

9.84

**

0.02

0.02

Water dependent

Culture

10.98

1.83

0.02

Tourist type

Error

Fishers LSD

2

2.47

3.57

*

0.02

454

0.69

Local residents > day and overnight visitors at p < 0.05

Pollution-degradation

0.02

Tourist type

Error

2

444

Fishers LSD

Local residents > day visitors at p < 0.01

Intrusive-high cost

2

24.93

11.83

***

Tourist type

Error

2

452

Fishers LSD

Gender

Local residents > day visitors at p < 0.01

Beach dependent

1

5.73

5.20

*

Error

Fishers LSD

403

NA

Education

Error

Fishers LSD

Income

Error

Fishers LSD

Income

Error

Fishers LSD

Employment

Error

Fishers LSD

Age

Error

Fishers LSD

0.01

Beach-sand

5.99

Bathing area-water

3.26

0.79

13.42

4.12

0.01

1.10

Water dependent

2

10.07

5.69

**

0.03

383

1.77

Matric or lower > diploma, degree and postgraduate at

p < 0.01

Intrusive-high cost

6

8.21

3.88

***

0.07

328

2.11

Earning over ZAR 431 000 < earning less at p < 0.05

Nonintrusive

6

3.40

2.17

*

0.04

333

1.57

Earning over ZAR 552 000 < earning less at p < 0.05

Values

3

4.41

4.06

**

0.03

399

1.09

Employed and retired > unemployed and students at

p < 0.05

Socialising bather

2

3.44

3.42

*

0.02

372

1.01

People 25 years old or under < older people at p < 0.05

Education

Error

Fishers LSD

3.83

1.03

3.53

0.02

0.06

Gender

Error

Fishers LSD

375

2.11

Matric or lower > diploma, degree and postgraduate at

p < 0.001

Nonintrusive

2

5.29

3.35

*

0.02

381

1.58

Matric or lower > diploma, degree and postgraduate at

p < 0.05

Water dependent

6

3.82

2.15

*

0.04

333

1.77

Earning over ZAR 431 000 < earning less at p < 0.05

Values

1

6.47

5.81

*

0.01

402

1.11

NA

Outlets-accommodation

1

7.51

6.93

**

0.02

413

1.08

NA

Age

Error

Fishers LSD

Intrusive-high cost

2

6.76

2.92

*

0.02

353

2.32

People 25 years old or under > older people at p < 0.05

Education

Error

Fishers LSD

Income

Error

Fishers LSD

Gender

Error

Fishers LSD

Author's personal copy

Lucrezi S., van der Walt M.F.

Table 2 (continued)

MS

p2

Treatment

df

MS

2.99

0.01

Age

Error

2

401

2.92

0.84

Treatment

df

Age

Error

2

404

Fishers LSD

People 25 years old or under < older people at p < 0.05 Fishers LSD

Beach-sand

2.13

0.71

p2

3.46

0.02

Hazards

People 25 years old or under < older people at p < 0.05

Age

Bathing area-water

2.37

3.08

Error

402

0.77

Fishers LSD

People 25 years old or under < older people at p < 0.05 Fishers LSD

Values

People over 40 years old < younger people at p < 0.05

Socialising bather

Age

Error

Fishers LSD

361

1.09

Error

People 25 years old or under < older people at p < 0.05 Fishers LSD

Length of stay

Error

Fishers LSD

194

2.19

Error

People staying five nights or less > people staying for Fishers LSD

longer at p < 0.05

7.68

7.02

**

0.02

0.04

Age

Outlets-accommodation

3.15

2.93

*

Error

372

1.07

Length of stay

Intrusive-high cost

Annual visitation 2

Error

342

Fishers LSD

8.01

Habitual

15.73

2.35

3.66

6.69

**

0.04

0.04

Length of stay

4.01

0.04

207

0.9

People staying five nights or less > people staying for

longer at p < 0.05

Outlets-accommodation

2

4.98

5.41

**

0.05

202

0.92

People staying five nights or less > people staying for

longer at p < 0.05

Annual visitation 2

Error

339

People visiting for 15 days or more > people visiting Fishers LSD

for less at p < 0.01

3.60

0.02

Water dependent

13.99

8.09

1.73

***

0.05

People visiting for 15 days or more > people visiting for

less at p < 0.01

Nonintrusive

Bathing area-water

Annual visitation 2

6.95

4.5

*

0.03

Annual visitation 2

2.29

3.06

*

0.02

Error

338

1.55

Error

374

0.75

Fishers LSD

People visiting for 15 days or more > people visiting Fishers LSD

People visiting for one or two nights > people visiting for

for less at p < 0.01

longer at p < 0.05

Values

Annual visitation 2

6.29

5.64

**

0.03

Error

339

1.11

Fishers LSD

People visiting for 15 days or more > people visiting

for less at p < 0.05

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

older people, and employed or retired people. Satisfaction

with retail and accommodation was greater among females

and younger people. However, younger people were less

pleased with beach and water quality compared with older

people. Some perceptions varied significantly from location

to location (Table 1). For example, beach and sand quality

scores were consistently lower for Camps Bay, Clifton 1st3rd, and Hartenbos. This was also the case of hazards scores,

with Muizenberg also receiving lower ratings. Cape Town

was generally perceived to be more polluted and degraded in

comparison with Mossel Bay.

The CCA for perceptions using motivations to visit as explanatory variables revealed two factors (Axis 1 and Axis 2)

accounting for 64 % and 36 % of the variance in the data,

respectively (Fig. 2). Permutation tests yielded no significant

effects for both axes (Axis 1 p = 0.44; Axis 2 p = 0.14). Nonetheless, the ordination biplot revealed noteworthy patterns.

Motivations to visit were highly intercorrelated. Canonical

coefficients between Axis 1 and motivations were 0.44 for

the middle aged group, 0.15 for the socialising bather group,

and 0.12 for the habitual group. The gradient in this axis was

defined as one from characteristics of anthropogenic nature

(e.g. construction, management) to mainly natural characteristics (e.g. beach morphodynamics). Canonical coefficients

between Axis 2 and motivations were 0.85 for the habitual

group, 0.66 for the middle aged group, and 0.62 for the

socialising bather group. The gradient of this axis was defined

as one from basic characteristics (e.g. good sand and water) to

more complex ones sought by beachgoers (e.g. good quality

accommodation). Projecting perception points along the

Author's personal copy

Beachgoers perceptions of sandy beach conditions: demographic and attitudinal influences, and the...

Fig. 2 Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) ordination biplot with motivations to visit (arrows) and perceptions of beach conditions

(closed circles) at the beaches studied (open circles)

motivation axes shows that overall, motivations to visit had a

positive influence on beachgoers' perceptions at Muizenberg,

Clifton 4th, and Santos, a negative influence at Clifton 1st-3rd,

and mixed influences at the remaining beaches (Table 3).

Motivations positively influenced perceptions of hygieneparking and culture, while negatively influencing perceptions of socioeconomics, crowding-pests, wildlife-landscape, and conservation (Table 3). The middle-aged motivation group had a negative influence on perceptions of

most physical, biological, and environmental features, and

of values (Table 3). Habitual motivations almost had an

opposite effect on perceptions, while the socialising bather

group had mixed influences, positive on perceptions of

beach quality, outlets, and values, and negative on perceptions of the bathing area and area for activities (Table 3).

The CCA for perceptions using recreational preferences as

explanatory variables revealed two axes accounting for 47 %

and 35 % of the variance in the data, respectively (Fig. 3).

Permutation tests yielded significant effects for Axis 2

(p = 0.001) but not for Axis 1 (p = 0.62). The canonical

coefficients between Axis 1 and recreational preferences were

0.69 for the intrusive group, 0.53 for the nonintrusive

group, 0.39 for the water dependent group, and 0.23 for the

beach dependent group. Coefficients between Axis 2 and preferences were 0.77 for the water dependent group, 0.39 for

the beach dependent group, 0.23 for the nonintrusive group,

and 0.01 for the intrusive group. The gradient of both axes

remained similar to the explanation of Fig. 2, with the exception that socioeconomics fell under the category of basic

characteristics sought by beachgoers (Axis 2). Preferences

for intrusive and nonintrusive recreation were highly

intercorrelated, with a strong positive influence on perceptions

of most human-made characteristics, and a negative influence

on perceptions of natural and socioeconomic characteristics

(Table 3). Preferences for water-dependent recreation had similar influences on perceptions, with the exception that pollution, socioeconomics, and values were viewed in a more positive light (Table 3). Different from other groups, beachdependent recreation preferences positively influenced perceptions of most physical, environmental, and socioeconomic

characteristics, although views on conservation and wildlifelandscape were still influenced negatively, together with perceptions of most human-made features (Table 3). Recreational

preferences had a positive influence on beachgoers' perceptions at Muizenberg, Camps Bay, and Hartenbos, with the

exception of intrusive and high cost recreation at Muizenberg,

and beach dependent recreation at Camps Bay and Hartenbos.

They had a negative influence at Clifton and Santos, with the

exception of beach dependent recreation at Clifton 1st-3rd and

Santos. And they had positive (intrusive and nonintrusive recreation) and negative (water dependent and beach dependent

recreation) influences at Diaz (Table 3).

Discussion

Sandy beaches provide a variety of services, allowing the

development of supporting infrastructure that can enhance

Author's personal copy

Lucrezi S., van der Walt M.F.

projections of centres of distribution along each motivation and

preference axis of CCA ordination biplots

Table 3 Main directions of influence of motivations to visit and

recreational preferences on perceptions of beach conditions; and across

the beaches under study. Positive and negative signs were obtained from

Motivations to visit

Culture

Hygiene-parking

Recreational preferences

Middle aged

Socialising bather

Habitual

Intrusive-high cost

Nonintrusive

Water dependent

Beach dependent

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

Safety-management

Outlets-accommodation

Area for activities

Hazards

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

Pollution-degradation

Values

Beach-sand

Bathing area-water

Socioeconomics

+

+

+

+

+

Wildlife-landscape

Crowding-pests

Conservation

Muizenberg

Camps Bay

+

+

+

+

+

+

Clifton 4th

Clifton 1st-3rd

Santos

Diaz

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

Hartenbos

Fig. 3 Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) ordination biplot with recreational preferences (arrows) and perceptions of beach conditions

(closed circles) at the beaches studied (open circles)

Author's personal copy

Beachgoers perceptions of sandy beach conditions: demographic and attitudinal influences, and the...

their use. However, they also carry vital functions for a variety

of species. While many studies have focused on the human

dimensions of sandy beaches as tourism and recreation attractions (Beerli and Martn 2004; Yoon and Uysal 2005;

Ramseook-Munhurrun et al. 2015), more research aimed at

understanding peoples' links with beaches as ecosystems is

required (Tunstall and Penning-Rowsell 1998; Ariza et al.

2014; Voyer et al. 2015). This study set out to explore beachgoers' perceptions of beach conditions. The information collected facilitated a discussion of adaptive beach management.

The results presented also highlighted the relevance of integrating users' views into the planning and management of

sandy beaches, an approach already advocated by ICZM.

Demographic heterogeneity

This study revealed that while Mossel Bay and Muizenberg

had a strong domestic, local, and loyal component, the

Cape Town visitors were more international and ephemeral.

Local beachgoers were driven by habitual motivations and

preferences for active recreation during holiday periods. Visiting tourists favoured passive recreation during weekdays,

and were more critical of beach quality, water quality, and

pollution.

People of different backgrounds may perceive the beach in

different ways, and have different attitudes towards it. Repeat

visitors or local users may either grow tolerant of situations

and phenomena on beaches, or take them for granted, or regard them as part of a natural process. They may perceive their

beaches to be in better condition than visitors do, as a reaction

to the threat that outsider assessments pose to place identity

(Bonaiuto et al. 1996). In contrast, first time visitors and international tourists may judge the conditions of a beach based

on other realities serving as a frame of reference (Baysan

2001; Beerli and Martn 2004; Kontogianni et al. 2014; but

see Roca et al. 2009). In this case, international visitors were

mainly northern European. Their favouring nonintrusive recreation and greater criticism concerning pollution may be partially explained by values, practices, and media attention regarding environmental issues in their country (Baysan 2001).

However, visitors sharing strong environmental awareness

may still require beaches to be adequately developed and

commercialised. They may not necessarily be willing to

incentivise beach protection. In contrast, local users may be

opposed to commercialisation and development in their area,

take responsibility for the degradation of their beaches, and be

willing to carry some financial costs required to improve

beach conditions. These contrasting attitudes can result from

the locals' sense of attachment and stewardship for their coast

as opposed to outsiders, different needs and preferences, and

different views on who should hold responsibility for beach

maintenance and protection (Baysan 2001; Oh et al. 2010). In

this study, visitors assigned lower ratings to the cultural

attributes of beaches. This may reflect a weaker sense of spiritual and cultural connection between outsiders and the

beaches they visit. In contrast, local users are more likely to

possess better knowledge of the cultural value of their

beaches, and to have established a bond with their beaches

through various experiences (Voyer et al. 2015). These people

normally perceive the beach to be a symbol that identifies their

town (Villares et al. 2006; Cervantes et al. 2008).

Female, older, affluent and educated beachgoers favoured

nonintrusive recreation. It is understandable that females accompanying children and older people tend to seek a tranquil

recreational experience. These groups also accorded greater

importance to the values of beach ecosystems, indicating

greater ecological sensibility compared with other beachgoer

groups. This sensibility may be attributed to greater responsibility, sensitivity, soft approaches, care, knowledge, experience, conservative ways, and more time available (Morgan

et al. 1993; Kontogianni et al. 2014; Leonidou et al. 2015).

A stable economic condition may also lead to better disposition towards conservation. Cinner and Pollanc (2004) have

used the Maslow hierarchy of needs (Maslow 1970) to argue

that conservation would be associated with complex needs

including belonging, esteem, knowledge, aesthetics, and

self-actualisation, and not with basic needs such as food and

security. Unless basic needs are fulfilled, conservation would

be difficult to pursue.

Sociodemographic influences on peoples perceptions of

beach environments have relevant implications for management, for example, the need to develop different communication strategies for different user groups, to diversify management plans across beaches with different uses, and to adapt

management plans to satisfy different user groups. To address

such sociodemographic influences, decision makers need to

focus on at least four tasks. The first is to address the concerns

of various user groups. The second is the establishment of

campaigns of education regarding the potential short-term

and long-term impacts, whether positive or negative, of proposed plans. The third is the design of marketing strategies

that will work for a balance between user demands and the

need to protect beach ecosystems. Lastly is the development

of co-management approaches aimed at providing users with a

sense of stewardship and responsibility for sandy beaches.

The common denominator of these tasks should be striving

for a sustainable beach management model, where environmental protection and the preservation of beach ecosystem

functions are prioritised, although not to the entire expense

of users.

Motivations to visit and recreational preferences

This study looked at commonly investigated concepts in tourism research, including motivations to visit and recreational

preferences. The information gained from these constructs,

Author's personal copy

Lucrezi S., van der Walt M.F.

and their influence on peoples evaluation of their recreational

environment, are relevant to understanding the dispositions of

people towards sandy beaches. Recreational orientations and

experiences can influence environmental behaviours of coastal users, potentially playing an educational role (Kontogianni

et al. 2014; Lee et al. 2015). Certain perceptions and views

may translate into willingness to learn, to adapt to regulatory

actions such as temporary beach closures and zoning, to financially support beach protection and conservation, to actively participate in management and science through volunteer work and citizen science, and to engage in environmentally responsible behaviours at home. For example, habitual

users who have developed a sense of emotional attachment to

the beach may be easily encouraged to participate in a volunteer programme (Lee 2011). Users who feel that their favoured

activities are threatened by environmental degradation may be

more inclined to pay for supporting scientific research aimed

at problem solving (Kontogianni et al. 2014).

In this study, motivations to visit were strongly

intercorrelated, influencing perceptions of most beach characteristics similarly. Motivations and recreational preferences

positively influenced perceptions of human-made features,

which were offered and maintained to varying degrees at all

the beaches studied. These results support the assumption that

people with different motivations to visit will assess their destination in a similar manner, if they feel that the destination

provides them with the sought-after resources (Beerli and

Martn 2004). Beachgoers may also be satisfied with the condition of services provided on beaches either because they do

not play a decisive role in beach enjoyment, or because they

can be sacrificed for the ultimate purpose thereof (Tudor and

Williams 2006; Roca et al. 2008; Snider et al. 2015).

Motivations to visit and recreational preferences negatively

influenced perceptions of biological and environmental factors, including wildlife abundance and diversity, crowding,

and conservation. Interestingly, perceptions of the socioeconomic state of the beaches were correlated with perceptions of

conservation and management (Fig. 2), and even physical and

environmental characteristics (Fig. 3). Beachgoers may perceive the environmental and ecological quality of beaches to

be dependent on the economic resources available to beach

managers. Such quality will be reflected in the investments

made by municipalities, districts, and the country. Beachgoers

can also see themselves as playing a role in financing beach

management. In this study, preferences for beach-dependent

recreation, favoured by domestic and international visitors,

positively influenced socioeconomic perceptions. Visitors

staying for a certain period tend to seek experiences in addition to beach recreation, spending more money in a municipality compared with local users (Roca and Villares 2008).

Being aware of the impact that their spending could exert on

the local economy, these users may opine that beaches indirectly benefit from this impact. Given their still unsatisfied

view of conservation and other natural features of the beaches

under study, they may be more critical of current money-using

policies by managing authorities.

Beachgoers generally favoured nonintrusive recreation,

possibly because intrusive activities such as four-wheel driving and camping are not allowed on the beaches studied.

However, this is not the first case of users giving poor credit

to aggressive recreation, particularly four-wheel driving on

sandy beaches (Priskin 2003; Maguire et al. 2011). Fourwheel driving in South Africa has been banned from most

beaches for more than fourteen years (Celliers et al. 2004).

Domestic beachgoers may have possessed knowledge of the

harmful impacts of four-wheel driving, probably thanks to

media influences and educational campaigns running alongside the implementation of the ban. However, to date no study

has yet set out to investigate peoples perceptions of largescale management interventions of the sort, but should be

contemplated in the future, as a means to assess the receptiveness of the public to managerial actions, and to assist the

development of new management plans.

Beach characteristics rated poorly

Beachgoers were sensitive to the state of physical and bioenvironmental features at some of the beaches studied.

Cape Town was perceived to be more polluted and degraded

compared with Mossel Bay, probably due to the urban nature

of the former, as opposed to a more semi-natural feel of the

latter. Beach configuration and hazards received lower ratings

in Clifton 1st-3rd, Camps Bay, Hartenbos, and Muizenberg.

Clifton 1st-3rd does not have a permanent lifesaving installation, and is not cleaned of washed-up kelp accumulations,

which can take beach space and emit an unpleasant odour.

Erosion was visible in Hartenbos, while Camps Bay was particularly crowded. Hazards in the bathing area may include rip

currents and the presence of great white sharks. Mitigation

measures to reduce the risk of rip current incidents are normally adopted on Blue Flag beaches, where boards are

installed to warn and instruct bathers. While these boards were

present on some of the beaches studied, they could have

remained unnoticed by beachgoers (Brannstrom et al. 2015).

Shark attack mitigation measures are also in place on South

African beaches (Kock et al. 2012), and beachgoers do possess some awareness of them (Lucrezi et al. 2015). However,

it may still take time before these initiatives gain momentum

and improve public perceptions of shark-associated risks.

Users' perceptions of beach configuration could represent a

difficult challenge to managers. Beach dimensions can be perceived negatively in urban beaches, where users are likely to

sense a lack of space compared with more natural scenarios

(Roca and Villares 2008). As a consequence, the demand for

space in urban beaches is likely to increase. Addressing such a

demand implies managing conflict between recreation and

Author's personal copy

Beachgoers perceptions of sandy beach conditions: demographic and attitudinal influences, and the...

conservation, or between capped recreation and overexploitation. An example is Clifton 1st-3rd, where cast-up kelp accumulations prevented beachgoers from occupying the beach

space. While managers may consider beach cleaning as an

option to alleviate the problem, this approach would have

negative ecological impacts (Mead et al. 2013). A win-win

solution should be to exploit the natural division of Clifton

into inlets, followed by education campaigns (perhaps run by

the Blue Flag programme at Clifton 4th) on the value and

function of wrack in beach ecosystems. Peoples demands

for beach space and amenities as well as wildlife and better

conservation initiatives may seem like paradoxical expectations to managers, which often derive from users' lack of understanding of the requirements of a healthy beach ecosystem

(Maguire et al. 2011). However, the coexistence of conservation and recreation on beaches can be worked out and should

be encouraged, for example, in scenarios of degraded beaches

subject to tourism declines (McLachlan et al. 2013). Further,

user demand for better management could reflect a real discontent with current management practices, especially when

one-sided and based on a priori decisions that have neglected

the public perspective (Maguire et al. 2011).

User evaluations may determine whether beaches retain

those attributes creating recreational experiences capable of

positively influencing environmental attitudes and behaviours. These experiences are education, aesthetics, escapism,

and experiential engagement (Pine and Gilmore 1998; Lee

et al. 2015). In this study, aesthetics was highly appreciated

by the beachgoers. Escapism and experiential engagement

were reflected in the motivation to relax and socialise and in

the preference for nonintrusive recreation. However, intrusive

activities such as collecting shells and motor boating/jet skiing

were still favoured among some people. Spirituality, a cultural

aspect normally indicating a strong bond with the coast, and

capable of predicting pro-environmental behaviours (Voyer

et al. 2015), was generally rated poorly by the participants;

likewise, education, among other conservation initiatives.

These findings imply a need to provide education about beach

ecosystems in various ways, and to implement tangible conservation programmes. Some of the beaches studied are Blue

Flag beaches, providing some education in the form of boards

and occasional activities such as beach clean-ups. These

efforts, however, did not seem to satisfy the participants'

desire to witness (and perhaps participate in) education and

conservation. Educational strategies may deploy modern

technologies, such as mobile phone applications, to disseminate environmental information and engage users in participatory coastal science (Merlino et al. 2014; Adriaens et al.

2015; Ghermandi et al. 2015). Initiatives promoting active

stewardship, such as simple beach litter campaigns or bird

monitoring, can strengthen spiritual bonds between users

and the coast (Storrier and McGlashan 2006; Ferreira et al.

2012; Voyer et al. 2015).

The participants' concern for beach conservation does not

guarantee willingness to participate in it if it were more tangible and accessible. While users wish for a beach with greater

wildlife abundance and diversity, they may not be interested in

participating in environmental monitoring, or be opposed to

restrictions that would compromise their recreational experiences. Generally users prefer moderate restrictions (Oh et al.

2010) and are capable of adapting when these are implemented (Maguire et al. 2013). Users can also be supportive of selftaxation to aid research, management, and conservation, especially when they realise that the long-term benefits to the ecosystem will also impact them positively (Shivlani et al. 2003;

Kontogianni et al. 2014). Therefore, the potential for public

participation in beach management and conservation should

be tapped.

Beach characteristics rated highly

Beachgoers placed great importance on the values associated

with beach ecosystems. These included inherent, fundamental, eudaimonistic, and instrumental values described by Jax

et al. (2013), and re-proposed by Schlacher et al. (2014) as a

perspective from which to address beach ecosystems, and design management and conservation plans. Beachgoers indirectly acknowledged the status of beaches as generators of

provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting services to

humankind. They also recognised the non-human rights of

beach ecosystems, and humankinds responsibility to protect

beaches. The recognition and importance attributed by users

to beach ecosystem values can be reflected in sentiments of

benevolence, manifested through actions of care and stewardship of the coast (Tunstall and Penning-Rowsell 1998;

Maguire et al. 2011; Voyer et al. 2015). These can range from

direct participation in volunteering and citizen science, to

more personal and informal ways of monitoring and reporting.

Appreciation of these values can also accompany a change of

the self-prescribed standards concerning the sustainable use of

resources and compliance with rules and regulations to protect

beaches.

The governance of coastal ecosystems should be

characterised by a better study and consideration of human

dimensions including values, images, and principles shared

by users (Voyer et al. 2015). This is also in line with prescriptions of ICZM (Schernewski 2014). Given that values, images, and principles shape different cultural models, the integration of these models into management and conservation

policies needs to be orchestrated in a balanced manner, and

will require the use of different engagement approaches

(Tunstall and Penning-Rowsell 1998; Maguire et al. 2011;

Voyer et al. 2015). Views are also likely to differ and cause

conflict among other stakeholder groups in beach management systems, including managers, politicians, municipal authorities, NGOs, academic institutions, and the private sector.

Author's personal copy

Lucrezi S., van der Walt M.F.

While the fragility of beach ecosystems is generally acknowledged, their protection is not necessarily ranked as a top priority by some of these groups (Ariza et al. 2014). Conflicting

views can retard decision making and hamper the effective

management of beach ecosystems. Further, certain values

may be underrepresented in a scenario of technocracy-driven

governance of sandy beaches (Ariza et al. 2014). In order to

embody the multiplicity of values underpinning sandy

beaches, the multiplicity of stakeholder groups involved

in these ecosystems needs to be properly represented. Addressing the needs that are dictated by the values each

stakeholder group holds is a complex socio-political and

financial matter. However, there are simple steps that can

initiate a dialogue of co-management, including participation opportunities in decision making, policy, planning,

implementation, and monitoring.

Conclusions

Sandy beaches are used by heterogeneous groups of users.

While these groups can differ greatly, they can all share concerns for the wellbeing of sandy beaches, as well as regard the

values underlying these fragile ecosystems. This was so in this

study. These attitudes could represent fertile ground in which

to plant the seed of proactive management including participatory planning, decision making, management, and science.

They are an invitation for testing new propositions including

zoning, conservation taxes, regulations, and restrictions. The

coexistence of uses and conservation remains a problematic

management issue, particularly in urban and tourism areas,

and where anthropogenic stressors exert chronic effects on

beach ecosystems (Roca and Villares 2008; McLachlan et al.

2013). Beach users may yet be far from understanding that

higher demands for conservation can translate into recreational constrictions. Research has demonstrated that proper educational campaigns can positively affect peoples disposition

towards a more sustainable management of beach resources,

including actions that will require compromise and restrictions

(Ormsby and Forys 2010). In this study, beachgoers may still

have been unable to properly discern the condition of various

beach properties. Further, this study could not take the full

diversity of beach types into consideration. Finally, beachgoers' perceptions need to be treated carefully before being

translated into management practices. Nonetheless, studies

such as this generate bottom-up information that can be crucial in the understanding of beach users' profiles. Such an

understanding is relevant in the context of differential beach

management, including the design of adaptive plans that will

prioritise the preservation of beach ecosystem functions, but

will also engender respect and foster positive connections between humans and sandy beaches.

Acknowledgments The authors wish to extend their gratitude to all the

beachgoers who participated in the beach survey, and to the fieldworkers.

This study was funded by TREES at the North-West University and the

National Research Foundation (NRF).

References

Adriaens T, Sutton-Croft M, Owen K, Brosens D, van Valkenburg J,

Kilbey D, Groom Q, Ehmig C, Thrkov F, Van Hende P,

Schneider K (2015) Trying to engage the crowd in recording invasive alien species in Europe: experiences from two smartphone applications in northwest Europe. Manag Biol Invasion 6(2):215225

Ariza E, Jimnez JA, Sard R, Villares M, Pinto J, Fraguell R, Roca E,

Marti C, Valdemoro H, Ballester R, Fluvia M (2010) Proposal for an

integral quality index for urban and urbanized beaches. Environ

Manag 45:9981013

Ariza E, Lindeman KC, Mozumder P, Suman DO (2014) Beach management in Florida: assessing stakeholder perceptions on governance.

Ocean Coast Manag 96:8293

Ballance A, Ryan PG, Turpie JK (2000) How much is a clean beach

worth? The impact of litter on beach users in the cape peninsula,

South Africa. S Afr J Sci 96:210213

Baysan SK (2001) Perceptions of the environmental impacts of tourism: a

comparative study of the attitudes of German, Russian and Turkish

tourists in kemer, Antalya. Tourism Geogr 3(2):218235

Beerli A, Martn JD (2004) Tourists characteristics and the perceived

image of tourist destinations: a quantitative analysisa case study

of lanzarote, Spain. Tourism Manag 25:623636

Blue Flag South Africa (2014) Retrieved March 20, 2014, from www.

blueflag.org.za

Bonaiuto M, Breakwell GM, Cano I (1996) Identity processes and environmental threat: the effects of nationalism and local identity upon

perception of beach pollution. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 6:

157175

Brannstrom C, Brown HL, Houser C, Trimble S, Santos A (2015) BYou

cant see them from sitting here^: evaluating beach user understanding of a rip current warning sign. Appl Geogr 56:6170

Celliers L, Moffett T, James NC, Mann BQ (2004) A strategic assessment

of recreational use areas for off-road vehicles in the coastal zone of

KwaZulu- natal, South Africa. Ocean Coast Manag 47:123140

Celliers L, Colenbrander DR, Breetzke T, Oelofse G (2015) Towards

increased degrees of integrated coastal management in the City of

Cape Town, South Africa. Ocean Coast Manag 105:138153

Cendrero A, Fischer DW (1997) A procedure for assessing the environmental quality of coastal areas for planning and management. J

Coastal Res 13(3):732744

Cervantes O, Espejel I, Arellano E, Delhumeau S (2008) Users perceptions as a tool to improve urban beach planning and management.

Environ Manag 42:249264

Cinner JE, Pollanc RB (2004) Poverty, perceptions and planning: why

socioeconomics matter in the management of Mexican reefs. Ocean

Coast Manag 47:479493

Cohen J (1973) Eta-squared and partial eta-squared in fixed factor

ANOVA designs. Educ Psychol Meas 33:107112

Colenbrander D, Cartwright A, Taylor A (2015) Drawing a line in the

sand: managing coastal risks in the city of cape town. S Afr Geogr J

97(1):117

Comrey AL (1973) A first course in factor analysis. Academic Press,

New York

Comrey AL, Lee HB (1992) A first course in factor analysis. Erlbaum,

Hillsdale

Davie A (2008) The Whale Trail of South Africa. 30 South Publishers,

Johannesburg, p. 144

Author's personal copy

Beachgoers perceptions of sandy beach conditions: demographic and attitudinal influences, and the...

De Ruyck AMC, Soares AC, McLachlan A (1995) Factors influencing

human beach choice on three South African beaches: a multivariate

analysis. GeoJournal 36(4):345352

De Winter JCF, Dodou D, Wieringa PA (2009) Exploratory factor analysis with small sample sizes. Multivar Behav Res 44:147181

Defeo O, McLachlan A, Schoeman DS, Schlacher TA, Dugan J, Jones A,

Lastra M, Scapini F (2009) Threats to sandy beach ecosystems: a

review. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 81:112

Ferreira MA, Soares L, Andrade F (2012) Educating citizens about their

coastal environments: beach profiling in the coastwatch project. J

Coast Conserv 16:567574

Fritz CO, Morris PE (2012) Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen 141(1):218

Ghermandi A, Galil B, Gowdy J, Nunes PALD (2015) Jellyfish outbreak

impacts on recreation in the Mediterranean sea: welfare estimates

from a socioeconomic pilot survey in Israel. Ecosyst Serv 11:140147

Greenacre M (2010) Canonical correspondence analysis in social science

research. In: Locarek-Junge H, Weihs C (eds) Classification as a tool

for research. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 279286

Hair J, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC (1995) Multivariate data

analysis, 4th edn. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey

Hammer ., Harper DAT, Ryan PD (2001) PAST: Paleontological statistics

software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electron

4(1):9. http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm

Harris LR (2012) An ecosystem-based spatial conservation plan for the

South African sandy beaches. Dissertation, Nelson Mandela

Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth

Harris LR, Nel R, Schoeman DS (2011) Mapping beach morphodynamics

remotely: a novel application tested on South African sandy shores.

Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 92:7889

Harris L, Nel R, Holness S, Schoeman D (2015) Quantifying cumulative

threats to sandy beach ecosystems: a tool to guide ecosystem-based

management beyond coastal reserves. Ocean Coast Manag 110:

1224

James RJ (2000) From beaches to beach environments: linking the

ecology, human-use, and management of beaches in Australia.

Ocean Coast Manag 43(6):495514

Jax K, Barton DN, Chan KMA, de Groot R, Doyle U, Eser U, Grg C,

Gmez-Baggethun E, Griewald Y, Haber W, Haines-Young R,

Heink U, Jahn T, Joosten H, Kerschbaumer L, Korn H, Luck GW,

Matzdorf B, Muraca B, Nehver C, Norton B, Ott K, Potschin M,

Rauschmayer F, von Haaren C, Wichmann S (2013) Ecosystem

services and ethics. Ecol Econ 93:260268

Klimley AP, Ainley DG (1998) Great white sharks: the biology of

carcharodon carcharias. Academic Press, San Diego, p. 517

Kock A, Titley S, Petersen W, Sikweyiya M, Tsotsobe S, Colenbrander

D, Gold H, Oelofse G (2012) Shark spotters: a pioneering shark

safety program in cape town, South Africa. In: Domeier ML (ed)

Global perspectives on the biology and life history of the white

shark. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp. 447466

Kontogianni A, Damigos D, Tourkolias C, Vousdoukas M, Velegrakis A,

Zanou B, Skourtos M (2014) Eliciting beach users willingness to

pay for protecting European beaches from beachrock processes.

Ocean Coast Manag 98:167175

Leatherman SP (1997) Beach rating: a methodological approach. J

Coastal Res 13(1):253258

Lee TH (2011) How recreation involvement, place attachment, and conservation commitment affect environmentally responsible behavior.

J Sustain Tourism 19(7):895915

Lee TH, Jan FH, Huang GW (2015) The influence of recreation experiences on environmentally responsible behavior: the case of liuqiu

island, Taiwan. J Sustain Tourism 23(6):947967

Leonidou LC, Coudounaris DN, Kvasova O, Christodoulides P (2015)

Drivers and outcomes of green tourist attitudes and behavior:

sociodemographic moderating effects. Psychol Market 32(6):

635650

Lozoya JP, Sard R, Jimnez JA (2014) Users expectations and the need