Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

BCOR 2000 Corporate Finance Lecture 2

Hochgeladen von

RyanCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

BCOR 2000 Corporate Finance Lecture 2

Hochgeladen von

RyanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Corporate

Finance

LECTURE 2

TOPIC 2: CORPORATIONS AND CAPITAL

MARKETS

Corporations | Ownership vs Control | Capital Markets | Federal

Reserve System | The NPV Decision rule | No-Arbitrage Principle

or The Law of One Price | No-Arbitrage Pricing | Risk Premium

Chapters covered: 1,3,4

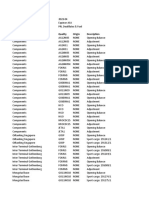

Corporations: Organizational Chart

Ownership vs Control

In corporations, ownership (shareholders) and control

(financial manager or CEO) are typically separated

Board of directors represents the interest of the

shareholders in the firm and monitor the major decisions

of the financial manager

Financial manager responsible for corporate investment,

financing, and shareholders payout policies

The objective of the financial manager should be to

maximize the net worth of the shareholders

Capital Markets

Capital markets allow investors who own a claim to a

firms assets to trade that claim with other investors

interested in acquiring such claim (e.g., stocks)

Capital markets can be transparent or opaque depending

on whether the prices at which investors trade are made

public or not

Transparent markets include stock markets and equity

options markets

Opaque markets include corporate bond markets and

credit default swaps markets

Federal Reserve System

Responsible (among other things) for setting and

implementing the nations monetary policy in pursuit of

maximum employment, stable prices and moderate longterm interest rates

The Federal Reserve (Fed) implements the monetary

policy by controlling the federal funds rate - the rate at

which depository institutions (e.g., banks) trade balances

(e.g., bank reserves) - in at least two ways:

Open market operations (purchase and sale of bonds)

Setting the reserve requirements for depository institutions

Time Value of Money

An insurance company approaches you with an

investment opportunity which promises $10,500, riskfree, next year, in exchange for $10,000 today. If the

savings (risk-free) rate is 3%, should you take it?

Time Value of Money

First note that $10,500 next year is not comparable to

$10,000 today

We need to transform today $ into next year $ or the

other way around

$10,000 today are equivalent to $10,300 = $10,000

*(1 + 3%) next year

Next year $ = compounded today $

Time Value of Money

$10,500

next year are equivalent to $10,194.175 =

$10,500/(1 + 3%) today

Today

$ = discounted next year $

To

answer the question we have to compare either

$10,500 and $10,300 or $10,000 and $10,194.175

Compare

$ values only if contemporaneous

Time Value of Money

1 2 3 are called the 3 rules of time travel

$10,500>$10,300

- take the opportunity

The

amount $10,300 can be thought of as the

opportunity cost

Opportunity

cost is the value of pursuing a riskequivalent alternative investment opportunity

In

our case, the alternative is saving

Time Value of Money

More generally, when evaluating an investment

opportunity, the discount rate used to transform future

$s into today $s is called the opportunity cost of

capital (OCC)

In our example, OCC = 3%

Net Present Value Decision Rule

An investment opportunity promises cash flows C0 at

time 0, C1 at time 1, ..., and CT at time T

The OCC for this opportunity is r

Then, the net present value (NPV) of this investment

opportunity is

C1

CT

NPV = C0 +

+

.

.

.

+

(1 + r)1

(1 + r)T

C0 is usually negative and captures the initial cost of the

investment opportunity

C1, ..., CT are usually positive, but not always

Net Present Value Decision Rule

Previous

example:

NPV = PV($10, 500)

PV($10, 000)

$10, 500

=

$10, 000

1 + 3%

= $194.175 > 0

Thus, our

investment opportunity has a positive NPV

Net Present Value Decision Rule

NPV Decision Rule: When choosing between

alternative investment opportunities, take the investment

opportunities with positive NPV

Investing in a positive-NPV investment opportunity is

equivalent to receiving its NPV in cash today

In other words the owner of the investment opportunity

is wealthier

Net Present Value Decision Rule

Example (Capital Budgeting and Ownership):

Firm ABC has $10 million in cash and an investment

opportunity that requires an immediate investment of

$10 mil in return for $15 mil, risk-free, next year.

ABC has two owners: Charles Sr (Mr. C) and Charles Jr.

(Chuck). Mr C is 80-years old while Chuck is 20-years

old.

Mr. C says that ABC should not take the investment

opportunity, but rather distribute a one-time dividend

of $10 million. Chuck says whatever. If the risk-free

rate is 5%, what should ABC do?

Net Present Value Decision Rule

Note the NPV of the project is positive:

NPV = PV($15mil)

PV($10mil)

$15mil

=

$10mil

1 + 5%

= $4.286mil > 0

Thus, according to the NPV Rule, ABC should take the

project. But...

Net Present Value Decision Rule

ABC has to make sure that its owners (Mr C and

Chuck) are better off as a result of taking the project

Is taking the project a better alternative to paying out

$10 mil in a one-time dividend?

The answer is YES

Net Present Value Decision Rule

ABC makes the following argument: If ABC takes the

project and the shareholders borrow (on their own

account) $10 mil at 5% for one year, then the

shareholders are better off compared to the alternative

of no investment and one-time dividend

To see this lets compare the cash flows

Net Present Value Decision Rule

Cash flows from investment + borrowing

Today

Next Year

$10 mil $4.5 mil = $15 mil - $10 (1 + 5%) mil

Cash flows from no investment + dividend

Today

Next Year

$10 mil

$0

Net Present Value Decision Rule

Regardless of shareholders preferences for the timing of

dividend distributions, firms should always invest in

positive NPV projects

To satisfy their time preference, shareholders can

borrow or lend on their own account against the NPV

of the project

Arbitrage in Capital Markets

Investment opportunities considered so far involve

trading (e.g., buying) real assets (e.g., projects)

Investment opportunities can also involve trading in

financial assets (e.g., stocks) or commodities (e.g., oil) on

specialized financial markets (e.g., NYSE or CBOE)

Arbitrage in Capital Markets

Notice that real assets do not trade on any market

(e.g., there is no market for projects)

An important consequence of this fact is that a real

asset can be worth different things to different firms

A positive NPV project for a firm can be a negative

NPV project for another firm

Arbitrage in Capital Markets

Unlike real asset, financial assets trade on a centralized

market

An important consequence of this fact is that all

investors agree on the value of the financial asset

A stock of IBM trading for $125 on NYSE is worth

$125 to everybody

Arbitrage in Capital Markets

We say that there are no arbitrage

opportunities in financial markets if one

cannot make a risk-free profit by purchasing/selling

financial assets in capital markets (i.e., no free lunches!)

An important consequence of the absence of arbitrage

opportunities is that the NPV of any investment

opportunity that involves purchasing/selling financial

assets is always zero.

The concept of no-arbitrage is related to the concept

of the informational efficiency of capital markets (to be

discussed later)

The Law of One Price

The Law of One Price (LOOP):

Two financial assets that have the same

payoffs must have the same prices

When there are no arbitrage opportunities in capital

markets the LOOP must hold!

The LOOP is sometimes called the No-Arbitrage

Principle

The Law of One Price

If the LOOP does not hold then there are arbitrage

opportunities

With no LOOP, two financial assets that have the same

exact payoffs can have different prices

An investor could make a quick risk-free profit by

short-selling (shorting) the expensive asset and

buying the cheap asset (longing).

Since this investment opportunity generates risk-free

profits, it is an arbitrage opportunity

The Law of One Price

A US T-Bill with maturity of 1 year and face value of

$1000 trades for $940 at the issuance. If the borrowing

rate is 5% per year, can you spot an arbitrage

opportunity?

The Law of One Price

Look for a financial asset with similar payoffs as the T-Bill

Today

-$940

Next Year

$1000

If you save (or lend) today X, your savings next year

equal X(1 + 5%)

Today

Next Year

-X

X*(1 + 5%)

The Law of One Price

We want a financial asset with similar payoffs as the TBill

X*(1 + 5%) = $1000 X = $952.38

If you save today $952.38 your savings next year will be

exactly $1000

However, you could get $1000 next year cheaper, by

just paying $940 for the bond

The Law of One Price

This

is an arbitrage opportunity

How

do you make money off it?

Go

short the expensive asset and long the cheap

asset

The

expensive asset is the savings opportunity.

Shorting this is equivalent to borrowing at 5%.

The Law of One Price

So

your arbitrage strategy is: Borrow $1000 at 5%

for 1 year and purchase a T-Bill with maturity 1-year

and face value $1000

Cash

flows:

Assets

Today

Next Year

Save at 5% (-1)

+$952.38

-$1000

T-Bill (+1)

-$940.00

+$1000

Risk-free Profit

+$12.38

$0

No-Arbitrage Pricing

The arbitrage strategy yields $12.38 today, risk-free

Of course you wont be the only one spotting this

opportunity

As more and more investors ride this opportunity, the

price of the bond approaches $952.38

Thus, the bond cannot trade for less or more than

$952.38, or else we have an arbitrage opportunity

We call the value $952.38, the no-arbitrage price

of the bond

No-Arbitrage Pricing

Recall the way we arrived at $952.38

$1000

$952.38 =

1 + 5%

Thus, the no-arbitrage price of the bond is the present

value of all the future cash flows promised by the bond,

discounted at the savings rate

More generally:

The No-arbitrage Price of a financial asset is the present

value of the future cash flows promised by the asset,

discounted at the appropriate discount rate

No-Arbitrage Pricing

One of your clients needs a price for the following stream

of sure flows

Asset

A

Today

?

6 months

$10 mil

1 year

$15 mil

You plan to use two US T-Bills with maturities of 6-month

and 1-year, respectively

Asset

Today

6 months

1 year

B1

$970

$1000

B2

$950

$1000

No-Arbitrage Pricing

You notice that you can use B1 to match the payoff of

asset A in 6 months and B2 to match the payoff of asset

A in 1 year

The necessary number of units are:

$10mil

Units of B1 =

= 10, 000

$1000

$15mil

Units of B2 =

= 15, 000

$1000

No-Arbitrage Pricing

The cash flows of the bonds portfolio are:

Asset

Today

6 months

1 year

+B1 (10,000)

-$9.7 mil

+$10 mil

+B2 (15,000)

-$14.25 mil

+$15 mil

Portfolio

-$ 23.95 mil

+$10 mil

+$15 mil

Notice that the bonds portfolio has the same exact payoffs

as asset A

Thus, by LOOP, it must be that the no-arbitrage price of A

is exactly $23.95 million

The Price of Risk

So far weve worked with sure or certain cash flows

In general cash flows are risky

Does the price of a financial asset with risky cash flows

reflect the risk of its cash flows?

The answer is YES, in general

The answer is no when investors do not care about risk

(we call them risk-neutral investors)

The Price of Risk

Consider the following example

Market index has different payoffs across states of the

economy risky cash flows

Average cash flow of the market index is

1100 = 800 * 0.5 + 1400 * 0.5

The Price of Risk

Notice that both the risk-free bond and the market

index have the same expected cash flows of 1100

However, market index trades at a discount relative to

risk-free bond

The price discount of 58 = 1058 - 1000 is

compensation demanded by investors for bearing the

cash flow risk of the market index

Notice that the price discount depends on the price of

the financial assets, and cannot be used to compare the

risk of two financial assets

The Price of Risk

The U.S. T-Bill has sure payoffs and consequently the rate of

return of the T-Bill is called the risk-free rate and is

denoted with rF

1100 1058

In our example, rF =

= 4%

1058

The Market Index has risky payoffs, and its rate of return is

risky as well

In this case we typically compute the average or expected

rate of return of the Market Index, denoted Er(Index)

800 0.5 + 1400 0.5

Er(Index) =

1000

1000

= 10%

The Risk Premium

The

difference between the expected return on the

Market Index and the risk-free rate measures the

compensation to the investors for bearing the risk of

the Market Index, when they invest in the Market

Index rather than the T-Bills

difference is called the Risk Premium and we

denote it with RP

This

In

our example, RP(Index) = Er(Index) - rF

RP(Index)

= 10% - 4% = 6%

The Risk-Adjusted Discount Rate

Recall that in order to compute the no-arbitrage price

of a financial asset we need to discount the future cash

flows of the asset with the appropriate discount rate

This discount rate is called the risk-adjusted

discount rate, denoted simply with r

When we know the risk premium of the asset, we can

compute the r as follows

r = rF + risk premium

Risk premiums can be computed with the Capital Asset

Pricing Model, or the CAPM (to be discussed later)

The Risk-Adjusted Discount Rate

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- What Is The Most Natural (Non-Autonomous, E.G. Breathing) Thing Done by Human Beings? How Often Does The Average Human Do It?Dokument32 SeitenWhat Is The Most Natural (Non-Autonomous, E.G. Breathing) Thing Done by Human Beings? How Often Does The Average Human Do It?RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 04. Data Manipulation in SQL IDokument16 SeitenLecture 04. Data Manipulation in SQL IRyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Tax Accounting Lesson 3Dokument50 SeitenPersonal Tax Accounting Lesson 3RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- SQL Ii:: Lab: Application of Selects and JoinsDokument16 SeitenSQL Ii:: Lab: Application of Selects and JoinsRyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 02. Introductory SQLDokument26 SeitenLecture 02. Introductory SQLRyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 03. ER DiagrammingDokument20 SeitenLecture 03. ER DiagrammingRyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap 010Dokument43 SeitenChap 010RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap 008Dokument43 SeitenChap 008RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- BCOR 2000 Lecture 3Dokument40 SeitenBCOR 2000 Lecture 3RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Finance: TOPIC 4: Real Assets and Pro-Forma Valuation (Capital Budgeting)Dokument59 SeitenCorporate Finance: TOPIC 4: Real Assets and Pro-Forma Valuation (Capital Budgeting)RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Finance Lecture 1Dokument38 SeitenCorporate Finance Lecture 1RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Quiz Acctng 603Dokument10 SeitenQuiz Acctng 603LJ AggabaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 4 Investment ClubDokument26 SeitenLesson 4 Investment ClubVictor VandekerckhoveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Profit and Loss Projection 1yr 0Dokument1 SeiteProfit and Loss Projection 1yr 0Suraj RathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 6 Self Test Taxation Discussion Questions PDF FreeDokument9 SeitenChapter 6 Self Test Taxation Discussion Questions PDF FreeJanjan RiveraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joint Venture 1Dokument11 SeitenJoint Venture 1Clif Mj Jr.100% (4)

- Transfer of SharesDokument12 SeitenTransfer of SharesromaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic Roundtable ReleaseDokument1 SeiteEconomic Roundtable Releaseapi-25991145Noch keine Bewertungen

- PTR MOSES CARLOS B. AGAWA - RESUME / CV - Updated December 2010Dokument12 SeitenPTR MOSES CARLOS B. AGAWA - RESUME / CV - Updated December 2010Ptr MosesNoch keine Bewertungen

- PNB V. Ca, Ibarrola: As Payments For The Purchase of MedicinesDokument5 SeitenPNB V. Ca, Ibarrola: As Payments For The Purchase of MedicinesKhayzee AsesorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Polaroid Corporation Case Solution Final PDFDokument8 SeitenPolaroid Corporation Case Solution Final PDFShirazeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business in Portuguese BICDokument26 SeitenBusiness in Portuguese BICRadu Victor TapuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1BS0 01 Que 20211123Dokument24 Seiten1BS0 01 Que 20211123Omar BNoch keine Bewertungen

- Format For Stock Statement in Case of Manufacturing/ProcessingDokument36 SeitenFormat For Stock Statement in Case of Manufacturing/ProcessingAjoydeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petition For Issuance of Letter of AdministrationDokument4 SeitenPetition For Issuance of Letter of AdministrationMa. Danice Angela Balde-BarcomaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MAINDokument80 SeitenMAINNagireddy KalluriNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCDDP AF Sub-Manual - Program Finance, Aug2021Dokument73 SeitenNCDDP AF Sub-Manual - Program Finance, Aug2021Michelle ValledorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes Receivable - Measurement and Determination of Interest ExpenseDokument6 SeitenNotes Receivable - Measurement and Determination of Interest ExpenseMiles SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Master Thesis Maarten VD WaterDokument92 SeitenMaster Thesis Maarten VD WaterkennemerNoch keine Bewertungen

- YTL Buys Rival Lafarge Malaysia: Corporate NewsDokument3 SeitenYTL Buys Rival Lafarge Malaysia: Corporate NewsSatesh KalimuthuNoch keine Bewertungen

- DO - 163 - S2015 - DupaDokument12 SeitenDO - 163 - S2015 - DupaRay Ramilo100% (1)

- Company Secretarial Practice - Part B - (E-Forms) PDFDokument721 SeitenCompany Secretarial Practice - Part B - (E-Forms) PDFAnonymous 5Hgrr4Q8JNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bangladesh-India DTAA PDFDokument7 SeitenBangladesh-India DTAA PDFmajumdar.sayanNoch keine Bewertungen

- McDonalds RoyaltyfeesDokument2 SeitenMcDonalds RoyaltyfeesNidhi BengaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2023-04 Valuation Report - PRL Destillates & FuelDokument6 Seiten2023-04 Valuation Report - PRL Destillates & FuelJianyun ZhouNoch keine Bewertungen

- CPM Guidant Corporation Shaping Culture Through Systems ChristoperDokument19 SeitenCPM Guidant Corporation Shaping Culture Through Systems ChristoperfreteerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ebook Percuma Tfs Price Action TradingDokument7 SeitenEbook Percuma Tfs Price Action TradingMUHAMMAD AL AMIN AZMANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Swing Trading MasteryDokument120 SeitenSwing Trading MasterySandro Pinna100% (5)

- FINANCIAL RISK MANAGEMENT TEST 1 AnswersDokument2 SeitenFINANCIAL RISK MANAGEMENT TEST 1 AnswersLang TranNoch keine Bewertungen

- China Shipowner DetailsDokument4 SeitenChina Shipowner DetailsTejasNoch keine Bewertungen

- HDFC Multi Cap Fund With App Form Dated November 2 2021Dokument4 SeitenHDFC Multi Cap Fund With App Form Dated November 2 2021hnevkarNoch keine Bewertungen