Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

On Gas Transport in Downward Slopes of Sewerage Mains PDF

Hochgeladen von

AlexOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

On Gas Transport in Downward Slopes of Sewerage Mains PDF

Hochgeladen von

AlexCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Revised submission (1) to Water Science and Technology, June 2009

On gas transport in downward slopes of sewerage mains

I. Pothof1,2*, F. Clemens2

1

Deltares | Delft Hydraulics, Department of Industrial Hydrodynamics, P.O. Box 177,

2600 MH Delft, The Netherlands.

2

Sanitary Engineering Group, Department of Civil Engineering and Geosciences,

Delft University of Technology, P.O. Box 5, 2600 AA Delft.

*Corresponding author, e-mail ivo.pothof@deltares.nl

ABSTRACT

Wastewater pressure mains are subject to gas pockets in declining sections. These gas pockets

cause an additional head loss and an associated capacity reduction, which cannot be predicted

with sufficient accuracy. This paper includes a critical review of the literature on gas transport

by flowing water in downward sloping pipes. This review shows that subtle misinterpretations

of the original data have caused the wide spread in the correlations for the clearing velocity,

as reported by various investigators. Finally, the paper proposes a new dimensionless velocity

parameter, which seems a more appropriate scaling parameter than the existing velocity

scaling.

KEYWORDS

channel flow; gas transport; sewerage; surface tension; two-phase flow; waste water pipelines.

Nomenclature

A

pipe cross section (m2)

xxxx

D

internal pipe diameter (m)

Eo

Etvs number, Eo

gD 2 (-)

F

Flow number (-)

Fr

Froude number (-)

~

2

g

gravitational acceleration (m/s )

n

dimensionless gas volume as the

number of filled pipe diameters (-)

Q

discharge (m3/s)

SE

Energy slope (-)

v

average velocity in pipe cross

section (m/s)

y

water depth (m)

Subscripts

B

buoyancy

c

clearing (velocity) i.e. for gas

pocket removal

e

effective

cf

clearing velocity including friction

I. Pothof, F. Clemens

downward pipe angle (rad)

density (kg/m3)

surface tension (N/m)

normalized quantity

xcrip

g

gas / air

i

initiation of downward gas

transport

w

water

Revised submission (1) to Water Science and Technology, June 2009

INTRODUCTION

Gas pockets in pipelines originate from a number of sources. Air may entrain continuously as

bubbles in case the sewer outflow is a free-falling jet into the pump pit. Air may also entrain

discontinuously after pump stop if the pump inertia is sufficient to drain the pit down to the

bell-mouth level. This kind of discontinuous air entrainment occurs mainly in wastewater

systems with a marginal static head. If the pipeline is subject to negative pressures during

normal operation or during transients, then air may leak into pipeline or may enter

intentionally via air valves. Another transient phenomenon, however more unlikely, is a pump

trip in a dendritic pressurised wastewater system. The induced transient may suck some

wastewater from an idle pumping station, causing air entrainment in the idle pumping station.

Another cause of gas pocket development consists of biochemical processes in the pipeline,

mainly producing carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen (N2) and methane (CH4).

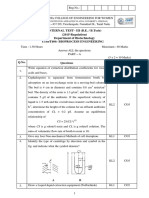

Figure 1. Gas entrainment in the hydraulic jump in a downward sloping pipe

Physical processes

Pressurised wastewater mains are characterized by an intermittent operation. Gas will

accumulate in elevated sections of the pipeline during shut down periods and dry weather

flow conditions. If an air pocket is present in the top of a declining section and liquid flows

through the conduit, then a hydraulic jump will develop at the tail of the gas volume. The

hydraulic jump entrains gas bubbles into the flowing liquid (Figure 1). The pumping action of

the hydraulic jump transports a fraction of the suspended bubbles down to the bottom of the

downward slope, as schematized in Figure 2.

The behaviour of the suspended bubbles has been investigated in a large-scale experimental

facility, erected at the wastewater treatment plant Nieuwe Waterweg in Hoek van Holland,

The Netherlands (Stegeman 2008). This facility, including a 40 m long 10 downward slope

with an elevation difference of 7 m, has been designed and operated by Deltares | Delft

Hydraulics and Delft University of Technology. The pipe internal diameter is 192 mm to

eliminate scale effects. Co-current air-water flow has been investigated at low air flow rates

from 0.7 l/min up to 10 l/min and at water flow rates up to 50 l/s. The experimental results

from this facility are currently being analysed and will be presented in detail in future

publications. The observations on the co-current flow of water and air reveals the following

flow regimes. If the flow number F, defined as F v gD , is smaller than 0.54, then only

one hydraulic jump is present in the downward slope near the bottom of the slope. If the flow

number F is greater than 0.54, then the suspended bubbles coalesce to the pipe soffit and grow

to a new gas volume with its own hydraulic jump. The maximum number of steady

On gas transport in downward slopes of sewerage mains

Revised submission (1) to Water Science and Technology, June 2009

consecutive hydraulic jumps in this 40 m downward slope was seven. The consecutive

hydraulic jumps moved upward very slowly or remained on a fixed position. A further

increase of the liquid flow rate up to a certain critical value reduces the length of the first gas

pocket and causes the suspended bubbles to coalesce into stable plugs that travel along the

pipe soffit at a smaller velocity than the average liquid velocity. These plugs are called stable,

because no gas bubbles are ejected from the plugs. The transition from consecutive hydraulic

jumps to stable plugs marks the clearing of gas pockets and reduces the additional gas pocket

head loss to zero.

hydraulic grade line

gas volume

hydraulic jump

suspended bubbles

stable plugs

Figure 2. Schematic overview of downward gas transport by flowing water.

Set-up of paper

This paper includes a review of the literature on gas transport by flowing water in declining

pipes. This review will show that the wide spread in the correlations for the clearing velocity,

as reported by (Wisner, Mohsen et al. 1975) and (Escarameia 2006), is mainly caused by a

subtle misinterpretation of the original data. Furthermore, new information from a few old

references will be presented and integrated into a synthesis of the available literature.

GAS TRANSPORT IN DOWNWARD SLOPING PIPES

This section provides an overview of available literature on gas transport in downward

sloping pipes. The literature contains intercomparable data on three different processes in

downward sloping pipes, namely:

1. The breakdown and transport of a large gas volume in the top of a downward sloping

pipe (Bliss 1942), (Kalinske 1943), (Lubbers 2007a) and (Stegeman 2008);

2. The transport of an individual gas pocket from which air bubbles are entrained into the

flowing liquid (Kent 1952), (Gandenberger 1957) and (Escarameia 2006) ; and

3. The transport of a stable plug (Veronese 1937), (Kent 1952) and (Wisner, Mohsen et

al. 1975).

The available literature to date does not explicitly distinguish these different processes and the

clearing velocity has been associated with all of these processes. The following paragraphs

discuss the literature on the three processes mentioned above.

Gas volume clearing

Among the oldest available research works in the field of liquid driven gas transport in

downward sloping pipes are the publications by Kalinske and Bliss (1943) and Kalinkse and

I. Pothof, F. Clemens

Revised submission (1) to Water Science and Technology, June 2009

Robertson (1943). They determined the dimensionless flow rate

Qi2

at which gas bubbles

gD 5

are ripped off from the gas volume by the hydraulic jump at the end of the gas volume and

start to move downward to the bottom of the slope. Kalinske and Bliss (1943) propose the

following relation for this incipient downward gas transport, based on experiments in a 100

mm and 150 mm pipe:

sin

Qi2

(1)

5

gD

0.71

where Kalinske et al. defined the pipe slope as the sine of the angle with the horizontal plane.

Kalinske and Bliss described three distinct flow regimes (Kalinske 1943):

A blow-back flow regime at relatively small discharges, although still above the

critical discharge in (1). In this flow regime, the bubbles coalesce and periodically

blow back upward, which limits the net gas transport. The net gas transport is

controlled by the flow characteristics below the hydraulic jump, which are described

by the flow number.

A full gas transport flow regime at higher discharges, at which all entrained gas

bubbles are transported to the bottom of the downward slope. The gas transport

becomes almost independent of the dimensionless velocity in this flow regime.

Kalinske et al. (1943) conclude that the Froude number upstream of the hydraulic

jump determines the gas transport. This Froude number is defined as: F1 v1

,

gye

where v1 is the water velocity upstream of the hydraulic jump and ye is the effective

depth, i.e. the water area divided by the surface width.

At the transition from the blow-back flow regime to the full gas transport flow regime,

a series of 2 to 4 stationary gas pockets and hydraulic jumps were observed in the

downward slope. The length of the downward slope of their test rig was 10.5 m long.

Blow-back did not occur any more in this transitional flow regime.

Equation (1) cannot be considered an equation for the clearing velocity, as explained by

Kalinske and Bliss: ..to maintain proper air removal, the actual value of the water discharge

should be appreciably larger than Qi (Kalinske 1943). Nevertheless, equation (1) has been

used as a correlation for the clearing velocity. In fact, equation (1) may depend on the length

of the downward slope, which was 10.5 m (i.e. 105*D for the 100 mm pipe and 70*D for the

150 mm pipe). Equation (1) is equivalent to a flow number criterion:

vi

Qi

4 Qi

4 sin

Fi

(2)

2

2

0.71

gD

gD

D gD

0.25 D

The transition to the full gas transport flow regime is highly relevant from a practical point of

view, because this transition represents the clearing velocity that breaks down gas pockets

(almost) completely and that minimises the head loss by the gas pockets. Bliss has reported

this transition in his research report only (Bliss 1942). The transition to full gas transport

requires a significantly larger dimensionless velocity than the more widely reported start of

downward gas transport according to equation (1). Figure 3 shows both correlations.

Bliss reported that the full gas flow occurred at lower water flow rates, if the gas pocket was

not held in position by the roughness of a joint or a projecting point gage. The results in

Figure 3 apply to the required velocities with a projecting point gage at the beginning of the

4

On gas transport in downward slopes of sewerage mains

Revised submission (1) to Water Science and Technology, June 2009

downward slope, because Bliss anticipated that any prototype pipe would contain sufficient

roughness elements to hold a gas pocket in position in the top of the downward slope. Finally,

Bliss noted that the 4 pipe required smaller clearing velocities than the 6 pipe.

Gas volume clearing velocity [-]

1.2

0.8

0.6

0.4

Full gas flow

Start gas flow

0.2

Lubbers (2007)

0

0

10

20

30

40

downward pipe slope [degrees]

Figure 3. Required dimensionless velocities for 'start of gas transport' (Kalinske 1943) and

clearing velocity in full gas flow regime (Bliss 1942) and Lubbers (2007a).

Lubbers (Lubbers 2007a), Tukker (2007) and Stegeman (2008) have performed experiments

in different pipe sizes from 80 mm to 500 mm at various downward slopes from 5 to 30 and

90. We have injected air upstream of the downward slope in a horizontal section and

measured the extra head loss due to the gas volume at different combinations of co-current air

water flow rates. The clearing velocity (or critical velocity) is reached when the extra head

loss due to the presence of the gas flow attains a minimum. This minimum value is close to

zero. Lubbers found that the largest clearing velocity is required at downward slopes of 10 to

20. Figure 3 shows a gradual drop in clearing velocity at slopes above 20. The

dimensionless clearing velocity drops to about 0.4 for a vertical pipe with 220 mm internal

diameter. An inter-comparison of the clearing velocities at a downward slope of 10 and the

three pipe sizes, revealed that the clearing velocity becomes constant for pipe diameters above

200 mm Figure 4.

I. Pothof, F. Clemens

Revised submission (1) to Water Science and Technology, June 2009

clearing velocity at 10 degrees [-]

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

At gas flow number 3e-4

0.3

At gas flow number 6e-4

0.2

0.1

Bubble clearing velocity

0

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

Pipe diameter [mm]

Figure 4. Clearing velocities at a downward slope of 10 from Lubbers, Tukker and

Stegeman. The three points in the bubble clearing velocity line are from Gandenberger

(1957), Mosvell (1976, extrapolated) and Escarameia (2006).

Individual gas pocket clearing

Kent (Kent 1952) has performed detailed experiments in a 33 mm pipe and a 102 mm (4 )

pipe on stationary gas pockets in declining pipes with downward angles varying between 15

and 60. The length of the downward slope was 5.5 m (18 ft or 54*D) for the 102 mm pipe.

Since the gas pockets are stationary, the flow regime is similar with Kalinskes transitional

flow regime between blow-back and full gas transport.

Kent focused on the determination of the drag coefficient, CD, as a function of the plug length,

Lb and the maximum projected plug area, Ab. Kents gas pockets were so large that a

hydraulic jump formed at the tail of the gas pocket. In order to maintain a constant gas

volume, Kent continuously injected air in the stationary pocket in the downward slope. He

measured the total gas volume in the downward slope by rapidly closing two valves at the

beginning and end of the slope simultaneously, after which he could measure the total gas

volume in the slope. This enabled Kent to determine the total buoyant force, which must

balance the drag force, because the gas pocket remained stationary. Kent established the

following relation from his experiments:

vc

1.23 sin

(3)

gD

A clearly better curve fit on Kents data, which allows for a non-zero offset is given in

equation (4); see (Mosvell 1976), (Lauchlan 2005) and (Wisner, Mohsen et al. 1975), who

first published the systematic deviation between Kents data and equation (3); see Figure 5.

vc

0.55 0.5 sin

(4)

gD

On gas transport in downward slopes of sewerage mains

Revised submission (1) to Water Science and Technology, June 2009

Equation (4) is valid for gas pockets with a dimensionless length exceeding 1.5D, which

coincides with a gas pocket volume exceeding 0.55D in full pipe diameters (n > 0.55).

Unfortunately, Equation (3) has been used frequently in the design of Dutch sewerage mains;

also for pipe angles smaller than 15. The significant difference between Kents equation (3)

and Mosvells curve fit (eq. (4)) is caused by Kents dimensional analysis that did not include

an offset parameter. The difference is particularly pronounced, if Kents equation is

extrapolated to pipe angles smaller than 15; see Figure 5.

1.4

0.9

1.2

1

0.7

0.6

0.8

0.5

0.6

0.4

0.4

0.2

Large pockets (Mosvell)

0.3

Large pockets (Kent)

0.2

Stable plugs

Gas plug length [-]

clearing velocities from

Kent [-]

0.8

0.1

Stable plug length

0

0

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Downward angle [deg]

Figure 5. Required dimensionless clearing velocities for large pockets with air entraining

hydraulic jumps and for stable pockets without air entrainment. The maximum stable pocket

length is indicated as well.

Figure 5 shows that the clearing velocity for stable individual plugs is smaller than the

clearing velocity for large pockets with hydraulic jumps and air entrainment. Figure 5

suggests that the clearing velocity for stable plugs and large pockets might become equal at a

downward slope of approximately 10, if Mosvells line and the stable plug line are

extrapolated to 10.

Gandenberger (1957) has performed measurements on individual stationary pockets and

pockets moving downward in various pipes with internal diameter between 10 mm and

100 mm at downward angles between 5 and 90. Most of Gandenbergers results are based

on measurements in a 45 mm glass pipe. Gandenberger measured a maximum clearing

velocity at 40. He investigated gas pocket volumes up to n = 1.5 and found that the gas

pocket velocity becomes constant if n exceeds 0.5 at all pipe angles, which confirms Kents

results. The applicability of Gandenbergers measurements for downward gas transport in

water pipelines has the same limitations as Kents results. A further limitation of

Gandenbergers measurements is the fact that Gandenberger did not inject air to maintain a

constant pocket volume. Hence, the bubbly flow at the tail of the hydraulic jump could not be

maintained during the experiments. Gandenbergers clearing velocities are slightly smaller

I. Pothof, F. Clemens

Revised submission (1) to Water Science and Technology, June 2009

than Kents velocities, which may be attributed to the smaller pipe diameter or to the lack of

air injection in the pocket.

Escarameia et al. (2006) have performed experiments in a 150 mm pipe with gas pockets up

to 5 litres (n = 1.9) and pipe slopes up to 22.5. Escarameia proposed the following formula

for the dimensionless clearing velocity, which extends Kents data, eq. (4), to angles smaller

than 15:

vc

0.61 0.56 sin

(5)

gD

The same limitations as mentioned for other individual gas pocket investigators apply to these

results.

Wisner (Wisner, Mohsen et al. 1975) developed an envelope curve from the available data

from Veronese (1937), Gandenberger, Kent and Kalinkse and found:

vc

0.825 0.25 sin

(6)

gD

It must be noted that Wisner et al. have misquoted Kalinske and Bliss in equation (1) by

using a coefficient 0.707 instead of the correct coefficient 1/0.71, which (incorrectly) resulted

in 30% smaller dimensionless clearing velocities.

Stable plug clearing

Kent (1952) also performed measurements on relatively small gas plugs from which no

bubbles were entrained by the hydraulic jump. These measurements reveal that both the

maximum stable plug length and the clearing velocity reduce at steeper slopes; see Figure 5.

Wisner (Wisner, Mohsen et al. 1975) recognized the large spread in proposed critical liquid

velocities for downward gas transport in the literature up to 1975 including Gandenberger

(Gandenberger 1957), Kalinske et al. (Kalinske 1943) and (Kent 1952). Wisner assumed that

scale effects could have caused the large spread and therefore performed experiments in a

large 245 mm pipe at a fixed downward angle of 18. Wisner focused on stable plugs rather

than the clearing velocity in his experiments.

DISCUSSION

Individual gas pocket clearing

If the results from the single-gas-pocket-investigators on their largest gas pockets are

compiled into one graph, then the trends are similar; see Figure 6. The only differences

between the results are caused by diameter differences, which induce a Reynolds number

influence and possibly a Etvs number influence. The Reynolds number influence is

included in the friction factor. A logical extension of the dimensionless clearing velocity is the

clearing velocity multiplied with f yielding:

f

(7)

vc

gD

In fact, this definition implies that the hydraulic grade lines are identical if the dimensionless

clearing velocities including friction, vcf , are identical, as illustrated for pipe diameters D1

and D2 in equation (8):

vcf

On gas transport in downward slopes of sewerage mains

Revised submission (1) to Water Science and Technology, June 2009

S E ( D1 )

S E ( D2 )

vcf ( D1 )

f

vD

gD1 1

2

f vD1

D1 2 g

2

f vD2

D2 2 g

f

vD

gD2 2

(8)

vcf ( D2 )

1.2

Bubble clearing velocity [-]

0.8

0.6

0.4

Escarameia (2006), 150 mm

Kent, Mosvell (1976), 100 mm

0.2

Gandenberger (1957), 45 mm

0

0

10

20

30

40

downward angle [degrees]

Figure 6. Clearing velocities of large individual bubbles.

0.14

Bubble clearing velocity

incl. friction factor [-]

0.12

0.1

0.08

0.06

Escarameia (2006), 150 mm

0.04

Kent, Mosvell (1976), 100 mm

0.02

Gandenberger (1957), 45 mm

0

0

10

20

30

40

downward angle [degrees]

Figure 7. Clearing velocities of large individual bubbles including friction factor.

I. Pothof, F. Clemens

Revised submission (1) to Water Science and Technology, June 2009

Assuming a relative wall roughness of 10-4 for all transparent pipes, the bubble clearing

velocity including friction as a function of the downward angle, shown in Figure 7, becomes

nearly independent of the pipe diameter. The analysis of these observations may proceed from

two perspectives. One possibility is that the result in Figure 7 is a coincidence and the surface

tension or Etvs number is still the dominant factor to explain the observed variation in the

clearing velocity at different pipe diameters. The other possibility is that the hydraulic grade

line is the dominant factor to explain the variation in the clearing velocity. A numerical

analysis of the applicable momentum balance should confirm whether the friction or the

surface tension explains the clearing velocity variation.

Gas volume clearing

The results on clearing velocities of gas volumes, Bliss (1942) and Lubbers (2007a), are

intercomparable, as illustrated in Figure 3.

A remarkable difference between Figure 6 and Figure 3 is the decreasing trend, measured by

Lubbers (2007) at pipe angles steeper than 10. The flow regime at the clearing velocity

explains this apparent inconsistency. If the liquid velocity exceeds Lubbers clearing velocity,

then the gas is transported as stable plugs downstream of the aeration zone of the hydraulic

jump. These stable plugs are significantly smaller than the large injected pockets. Since the

stable plug size and plug clearing velocity both reduce with the pipe angle, Lubbers clearing

velocity reduces as well. This process is not included in the experiments with individual gas

pockets, injected in the slope. Hence the experimental facilities with gas injection upstream of

the downward slope provide a more complete picture of the transport processes in the pipe

slope.

CONCLUSIONS

A critical review of the existing literature on the clearing velocity of gas pockets in downward

sloping pipes has revealed new information on the gas pocket clearing velocity (Bliss 1942)

and the stable plug clearing velocity (Kent 1952).

The paper has shown that the wide spread in available correlations for the clearing velocity is

caused by:

different diameters smaller than 200 mm. A pipe diameter of 200 mm or greater is

required to eliminate the diameter influence,

wrongful comparison of different processes, i.e.

o individual gas pocket transport has been compared with gas volume clearing

and

o initiation of gas transport has been compared with complete gas clearance.

The existing literature has been analyzed and integrated to explain the opposing trends of the

clearing velocity at increasing pipe angle. If the gas pockets are initiated upstream of the

downward slope, then the clearing velocity drops at pipe angles greater than 10 to 20. This

reduction in clearing velocity is caused by the flow regime with stable plug flow. These stable

plugs become smaller at steeper downward slopes, requiring smaller velocities to transport the

stable plugs along the pipe soffit.

An intercomparison of the single gas pocket clearing velocities shows a systematic increase of

the clearing velocity at a pipe diameter increase from 45 mm to 150 mm. An alternative

10

On gas transport in downward slopes of sewerage mains

Revised submission (1) to Water Science and Technology, June 2009

f

vc , seems to explain the clearing

gD

velocity variation with pipe diameter, but a numerical analysis still has to confirm this

analysis from the available experimental results.

dimensionless clearing velocity, defined as vcf

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to thank the participants of the CAPWAT project for publication of this

work.

REFERENCES

Bliss, P. H. (1942). The removal of air from pipelines by flowing water. J. Waldo Smith hydraulic fellowship of

ASCE. Iowa, Iowa institute of hydraulic research: 53.

Escarameia, M. (2006). "Investigating hydraulic removal of air from water pipelines." Water Management

160(WMI): 10.

Gandenberger, W. (1957). Uber die Wirtschaftliche und betriebssichere Gestaltung von Fernwasserleitungen.

Munchen, R. Oldenbourg Verlag.

Kalinske, A. A., Bliss, P.H. (1943). "Removal of air from pipe lines by flowing water." Proceedings of the

American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) 13(10): 3.

Kalinske, A. A., Robertson, J.M. (1943). "Closed Conduit Flow." Transactions of the American Society of Civil

Engineers (ASCE) 108(paper 2195): 3.

Kent (1952). The entrainment of air by water flowing in circular conduits with downgrade slope. Berkeley,

California, University of Berkeley. PhD.

Lauchlan, C. S., Escarameia, M., May, R.W.P., Burrows, R., Gahan, C. (2005). Air in Pipelines, a literature

review, HR Wallingford: 92.

Lubbers, C. L. (2007a). On gas pockets in wastewater pressure mains and their effect on hydraulic performance.

Civil engineering and Geosciences. Delft, Delft University of Technology. PhD: 290.

Mosvell, G. (1976). Luft I utslippsledninger (Air in outfalls). Prosjektkomiten for rensing av avlpsfann

(project committe on sewage). Oslo, Norwegian Water Institute (NIVA).

Stegeman, B. (2008). Capaciteitsreductie ten gevolge van gasbellen in dalende leidingen (Capacity reduction due

to gas pockets in downward sloping pipes). Civil Engineering. Zwolle, Hogeschool Windesheim. BSc: 62.

Tukker, M. J. (2007). Energieverlies in dalende leidingen ten gevolge van gasbellen (head loss in downward

pipes caused by gas pockets). Delft, Deltares | Delft Hydraulics: 48.

Veronese, A. (1937). "Sul motto delle bolle d'aria nelle condotto d'acqua (Italian)." Estrato dal fasciacolo X

XIV: XV.

Wisner, P., F. N. Mohsen, et al. (1975). "REMOVAL OF AIR FROM WATER LINES BY HYDRAULIC

MEANS." ASCE J Hydraul Div 101(2): 243-257.

I. Pothof, F. Clemens

11

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- An Up-Close Look at Electropositive FiltrationDokument8 SeitenAn Up-Close Look at Electropositive FiltrationAlex100% (1)

- Considerations For Estimating The Costs of Pilot-Scale FacilitiesDokument9 SeitenConsiderations For Estimating The Costs of Pilot-Scale FacilitiesAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measuring Dust and Fines in Polymer PelletsDokument6 SeitenMeasuring Dust and Fines in Polymer PelletsAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Benefits of Two-Stage DryingDokument3 SeitenThe Benefits of Two-Stage DryingAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Onsite Nitrogen Generation Via PSA TechnologyDokument4 SeitenOnsite Nitrogen Generation Via PSA TechnologyAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- LLPDE Production Using A Gas-Phase ProcessDokument1 SeiteLLPDE Production Using A Gas-Phase ProcessAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chlorine Production From NaCl (Chlor-Alkali)Dokument1 SeiteChlorine Production From NaCl (Chlor-Alkali)Alex100% (1)

- Re Establishing CourseDokument5 SeitenRe Establishing CourseAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Challenges of Handling Filamentous and Viscous Wastewater SludgeDokument7 SeitenChallenges of Handling Filamentous and Viscous Wastewater SludgeAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heat Transfer in Wiped Film EvaporatorsDokument4 SeitenHeat Transfer in Wiped Film EvaporatorsAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sampling For Internal CorrosionDokument1 SeiteSampling For Internal CorrosionAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- AODD Pumps in Chemical ProcessesDokument7 SeitenAODD Pumps in Chemical ProcessesAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using Excel VBA For Process-Simulator Data ExtractionDokument4 SeitenUsing Excel VBA For Process-Simulator Data ExtractionAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Piping Codes - What The CPI Engineer Should KnowDokument11 SeitenPiping Codes - What The CPI Engineer Should KnowAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aluminum Chloride ProductionDokument1 SeiteAluminum Chloride ProductionAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agglomeration ProcessesDokument1 SeiteAgglomeration ProcessesAlex100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Basic of An Electrical Control PanelDokument16 SeitenBasic of An Electrical Control PanelJim Erol Bancoro100% (2)

- 06-Apache SparkDokument75 Seiten06-Apache SparkTarike ZewudeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phase 1: API Lifecycle (2 Days)Dokument3 SeitenPhase 1: API Lifecycle (2 Days)DevendraNoch keine Bewertungen

- PVAI VPO - Membership FormDokument8 SeitenPVAI VPO - Membership FormRajeevSangamNoch keine Bewertungen

- 09 WA500-3 Shop ManualDokument1.335 Seiten09 WA500-3 Shop ManualCristhian Gutierrez Tamayo93% (14)

- A PDFDokument2 SeitenA PDFKanimozhi CheranNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Financial RulesDokument9 SeitenGeneral Financial RulesmskNoch keine Bewertungen

- M J 1 MergedDokument269 SeitenM J 1 MergedsanyaNoch keine Bewertungen

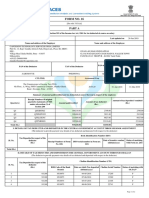

- Form16 2018 2019Dokument10 SeitenForm16 2018 2019LogeshwaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blade Torrent 110 FPV BNF Basic Sales TrainingDokument4 SeitenBlade Torrent 110 FPV BNF Basic Sales TrainingMarcio PisiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ikea AnalysisDokument33 SeitenIkea AnalysisVinod BridglalsinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 8: ACCG3001 Organisational Planning and Control Tutorial In-Class Exercise - Student HandoutDokument3 SeitenWeek 8: ACCG3001 Organisational Planning and Control Tutorial In-Class Exercise - Student Handoutdwkwhdq dwdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catalog Celule Siemens 8DJHDokument80 SeitenCatalog Celule Siemens 8DJHAlexandru HalauNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intermediate Accounting (15th Edition) by Donald E. Kieso & Others - 2Dokument11 SeitenIntermediate Accounting (15th Edition) by Donald E. Kieso & Others - 2Jericho PedragosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Subqueries-and-JOINs-ExercisesDokument7 SeitenSubqueries-and-JOINs-ExerciseserlanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MRT Mrte MRTFDokument24 SeitenMRT Mrte MRTFJonathan MoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- ESG NotesDokument16 SeitenESG Notesdhairya.h22Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fedex Service Guide: Everything You Need To Know Is OnlineDokument152 SeitenFedex Service Guide: Everything You Need To Know Is OnlineAlex RuizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employees' Pension Scheme, 1995: Form No. 10 C (E.P.S)Dokument4 SeitenEmployees' Pension Scheme, 1995: Form No. 10 C (E.P.S)nasir ahmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Level 3 Repair: 8-1. Block DiagramDokument30 SeitenLevel 3 Repair: 8-1. Block DiagramPaulo HenriqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- QA/QC Checklist - Installation of MDB Panel BoardsDokument6 SeitenQA/QC Checklist - Installation of MDB Panel Boardsehtesham100% (1)

- BYJU's July PayslipDokument2 SeitenBYJU's July PayslipGopi ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Activity Description Predecessor Time (Days) Activity Description Predecessor ADokument4 SeitenActivity Description Predecessor Time (Days) Activity Description Predecessor AAlvin LuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MDOF (Multi Degre of FreedomDokument173 SeitenMDOF (Multi Degre of FreedomRicky Ariyanto100% (1)

- Fernando Salgado-Hernandez, A206 263 000 (BIA June 7, 2016)Dokument7 SeitenFernando Salgado-Hernandez, A206 263 000 (BIA June 7, 2016)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNoch keine Bewertungen

- DC Servo MotorDokument6 SeitenDC Servo MotortaindiNoch keine Bewertungen

- TAS5431-Q1EVM User's GuideDokument23 SeitenTAS5431-Q1EVM User's GuideAlissonNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACIS - Auditing Computer Information SystemDokument10 SeitenACIS - Auditing Computer Information SystemErwin Labayog MedinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BCG - Your Capabilities Need A Strategy - Mar 2019Dokument9 SeitenBCG - Your Capabilities Need A Strategy - Mar 2019Arthur CahuantziNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ces Presentation 08 23 23Dokument13 SeitenCes Presentation 08 23 23api-317062486Noch keine Bewertungen