Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

763 767

Hochgeladen von

Nasr-edineOuahaniOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

763 767

Hochgeladen von

Nasr-edineOuahaniCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Language for specific purposes (LSP) SYNTHESIS 2015

International Scientific Conference of IT and Business-Related Research

ESP COURSE DESIGN FOR THE 21ST CENTURY:

TEAM TEACHING AND HYBRID LEARNING

KURS ENGLESKOG JEZIKA ZA POSEBNE NAMENE U XXI VEKU:

TIMSKA NASTAVA I HIBRIDNO UENJE

Dragana Spasi1, Anita Jankovi1, Milica Spasi-Stojkovi2

1

Faculty of Philosophy, KosovskaMitrovica, Serbia

Business School of Applied Studies, Blace, Serbia

Abstract:

This paper aims to promote higher foreign language competences in

both students and academic staff by implementing hybrid learning

approach and team-teaching strategy in ESP course design. Teamteaching of a language teacher and a content instructor contributes

to the direct and practical use of the language in the context of the

study field, which in turn further enhances the learning experience.

In addition, in hybrid learning, each delivery mode serves as a tool

allowing for differentiated instruction and successful task completion.

Firstly, the paper will review relevant theory and research literature

discussing the benefits and drawbacks of interdisciplinary team teaching strategy. Secondly, it will outline a hybrid course of English for

Computer Programming demonstrating how hybrid learning and teamteaching can be used as a basis for ESP university courses. Furthermore,

it will tackle unified learning outcomes and assessment, and present

a virtual classroom where the language and content intertwine. The

prospective course is designed to be delivered at the Business School

of Applied Studies in Blace and the University of Pritinas Centre for

Training and Development in Kosovska Mitrovica.

Apstrakt:

Ovaj rad ima za cilj da promovie vee jezike kompetencije kod

studenata i nastavnog osoblja kroz primenu hibridnog pristupa u

uenju i strategije timske nastave u izradi i realizaciji kurseva engleskog

jezika za posebne namene.Timski rad nastavnika jezika i poznavaoca

strunih termina u nastavi vodi ka direktnoj i praktinoj upotrebi

jezika u datoj oblasti, to zauzvrat unapreuje kvalitet samog procesa

uenja. Takoe, kod hibridnog uenja, svaki vid isporuke moe se

posmatrati kao sredstvo koje doprinosi raznolikosti samog procesa

nastave i uspenoj realizaciji zadatih ciljeva.

Na samom poetku emo se pozabaviti relevantnim teorijama i

strunom literaturom koja se bavi prednostima i nedostacima strategije

interdispilinarnog timskog uenja. Nakon toga, daje se prikaz hibridnog kursa iz engleskog jezika u oblasti kompjuterskog programiranja

koje pokazuje kako hibridno uenje i timska nastava zajedno mogu

predstavljati osnovu za izradu kurseva jezika za posebne namene na

univerzitetima. Osim toga, rad se bavi jedinstvenim ishodima uenja

i procene, i nudi prikaz virtuelne uionice u kojoj se prepliu jezik

i sadraj. Potencijalni kurs je dizajniran za potrebe Poslovne kole

strukovnih studija u Blacu i Centra za obuku i razvoj u Kosovskoj

Mitrovici, Univerziteta u Pritini.

Key words:

English for Specific Purposes, interdisciplinary team teaching, hybrid

learning, Content and Language Integrated Learning.

Kljune rei:

engleski kao jezik struke, interdisciplinarna timska nastava, hibridno

uenje, integrisano uenje sadraja i jezika.

Instructional roles are so diverse and require such different mixes

of tasks, talents, and temperaments that the smaller parts must be

played by more than one person.

James L. Bess (2000)

1. INTRODUCTION

Teaching a foreign language for specific purposes (FSP) is

always of paramount importance in all educational contexts

(Kaur, 2007). Our students as future professionals depend on

proficient foreign language skills; knowing a foreign language

specific to their study field increases their employability and

mobility. Higher Education Ministers within the European

Commission have established that the development of professional competences, including foreign language skills, is the primary objective of the 21st century universities (Communiqu,

2009). The main issue with FSP course design is that the mechanics are not flat; simply determining the aim through needs

analysis and matching it to the method to attain it. Furthermore, as Anthony identified, in FSP there is a still unresolved

discussion on whether the language teacher should be an expert

in the target subject of the class (2007).

E-mail: anita.jankovic@pr.ac.rs

This paper aims to promote higher foreign language competences in both students and academic staff by implementing

hybrid learning approach and team-teaching strategy. Firstly,

the paper will review relevant theory and research literature discussing the benefits and drawbacks of interdisciplinary team

teaching. Secondly, it will outline an integrative course of English for Computer Programming demonstrating how hybrid

learning and team-teaching combined can be used as a basis

for FSP university courses. Furthermore, it will tackle unified

learning outcomes and assessment, as well as present a virtual

classroom where the language and content intertwine.

2. ESP COURSE DESIGN AND TEACHER

COMPETENCES

Dudley-Evans (1998) outlines absolute and variable characteristics of English for specific purposes (ESP). The absolutes

denote a course which: a) caters for learners needs; b) employs

methodology characteristic for the study field it serves; and c)

pivots on language elements appropriate for the study field. On

the other hand, it is assumed that the course is designed for a

specific discipline, mainly for adult learners at the tertiary level

DOI: 10.15308/Synthesis-2015-763-767

763

SYNTHESIS 2015 Language for specific purposes (LSP)

who are at the intermediate or advanced level with the basic

grasp of the language system. In other words, ESP is studentcentered language learning in synergy with a particular content

subject or study field. However, several practical concerns arise

from these characteristics (Nunan, 1987). Firstly, Nunan argues

that every ESP course should promote communication competences in professional settings. This could be achieved by even

distribution of specific and general language learning. Furthermore, the author points out that the course materials should be

easily adaptable and constantly developed.

Secondly, a single most important concern in the ESP course

design is the teacher (content, professional) knowledge. The

concept of teacher knowledge is three-dimensional; the primary

element is the cognition of the target language, its system, and

specific discourse; secondly, a teachers grasp of the academic

discipline which the ESP serves; and finally, cognition of the foreign language methodology and theories of learning (GrskaPorcka, 2013). A teacher would gain the theoretical knowledge

in the academic context, but more importantly performance

skills are gained through work experience and professional

development. The specialist knowledge has been a stumbling

block of ESP; teacher competences have often been questioned

and doubted due to the lack of understanding of the content

subjects. Bell reports the opinion that an ESP teacher could not

teach the particular language context without understanding

the study field, moreover, without having deep insights into the

field (2002). Therefore, the peculiarities of the ESP would be lost

to such a teacher.

3. INTERDISCIPLINARY TEAM TEACHING

764

One possible solution to the concerns expressed in the previous section is the introduction of interdisciplinary team teaching ESP courses. Buckley states that the foremost argument in

favor of curriculum integration is the disconnection between

a discipline-based curriculum and the real world (2000). In

addition, Barron emphasizes that cognitive and communicative competences cannot be separated (1992). Consequently, to

empower ESP teachers in ensuring that language and academic

skills are developed simultaneously they should be paired up

with subject specialists. Selinker calls them informants and

proceeds with sarcasm when saying that they provide the naive

ESP teacher with insights on the content and the organization

of texts and on the processes of their subject (1979). Nevertheless, Barron proposes three methods of cooperation that fit the

framework of this paper. However, we will firstly define team

teaching and provide arguments and evidence gathered from

the survey of relevant theory and research literature supporting

the value of this strategy.

Team teaching, parallel teaching, supportive or complementary teaching, collaborative teaching, co-teaching, these are just

several names for one and the same strategy where two or more

teachers work together with the same aim for the same group of

students. Additionally, Buckley supplements this definition with

determiners such as purposefully, regularly, and cooperatively

(2000). There are two categories differentiated by whether the

teaching team shares the physical space (the classroom) or not.

True team teaching involves ESP teacher and subject specialist

co-operating fully throughout the course, delivering instruction

simultaneously in the same classroom (Barron, 1992; Dinitz et

al., 1997). In similar fashion, Conderman and McCarty define

it as a strategy where a group of teachers work together, plan,

conduct, and evaluate the learning activities for the same group

of students (2003). For the purpose of this paper, we adopt

DOI: 10.15308/Synthesis-2015-763-767

the term team teaching as defined by Buckley who describes

two teachers who bring to the table their distinct and complementary sets of skills, combine roles and share resources and

responsibilities in a sustained effort while working towards the

common goal of academic success (2000).

There are many considerations to be made to ensure the success of this strategy. Little and Hoel emphasize the importance

of careful selection of the teaching partner. Furthermore, they

warn the teachers to manage their expectations as well as to ask

themselves whether they can remain open-minded, share control, and not become easily offended (2011). Stewart and Perry

recommend committing to the practice of reflective teaching

and being open to share and accept what others offer (2005).

Finally, Leavitt reports a mock Decalogue of two Stanford University professors who summed up the rules for a successful

teaching team (2006):

1. Thou shalt plan everything with thy neighbor.

2. Thou shalt attend thy neighbors lectures.

3. Thou shalt refer to thy neighbors ideas.

4. Thou shalt model debate with thy neighbor.

5. Thou shalt have something to say, even when thou art

not in charge.

6. Thou shalt apply common grading standards.

7. Thou shalt ask open questions.

8. Thou shalt let thy students speak.

9. Thou shalt attend all staff meetings.

10. Thou shalt be willing to be surprised.

Research literature indicates that once the conditions are

right, team teaching has numerous student, teacher, and professional benefits. The most general and far-fetching benefit of

the presence of the interdisciplinary faculty member is that it

reinforces the importance of alternative viewpoints and perspectives (Little &Hoel, 2011). Similarly, Fenollera et al. state

that team teaching provides multiple learning perspectives and

promotes teamwork and communication between teachers and

students (2012). In addition, Leavitt points out that it provides

instructors with a useful way of modeling thinking within or

across disciplines (2006).

Conderman and McCarty believe that by pooling the resources, materials, experiences, and strengths, the classroom

experience is richer than if the course had been taught independently; teachers benefit from the spirit of parity where

both sides are equally valued and have executive power (2003).

Buckley reinforces this notion by suggesting that teachers express parity by playing the dual roles of teacher and learner,

expert and novice, giver and recipient of knowledge or skills

(2000). Finally, professional benefits spring from the concept

of teacher knowledge (Grska-Porcka, 2013) where the fourth

dimension is added, and it refers to cognition of ones own behaviour and habits.

As previously mentioned, Barron devised three types of interaction in team teaching (1992). They range from the least

involvement of the specialist to the full integration of the disciplines. The first is the consultative method where the subject

specialist is brought into advice in certain stages of the course

delivery. Secondly, there is the collaborative method in which

the teaching team works together on all course aspects except

for the shares the classroom. Finally, the intervention method

implies teaching in a shared physical space. In view of our proposed model course, we opted for the combination of the second and the third method as our teaching team does not share

the brick-and-mortar classroom, but they do deliver the joint

instruction in the virtual learning environment.

4. THE MODEL ESP COURSE

The Business School of Applied Studies in Blace comprises

the following study programmes: Computing and Informatics,

Finance and Accounting, Taxes and Customs, Management and

International Business Administration, and Tourism. All students are required to take English language courses throughout

the three years of their BA studies. Due to various organizational requirements, students of two, or even three study programs used to attend English classes together. Therefore, a general business English course was selected to try to accommodate

the professional needs of all of them, as well as various levels of

their language competences.

However, this represented a great impediment for both the

students and English teachers, as it was difficult to work with

such large groups whose interests and needs differed to a great

extent. Several trials with teaching materials referring to specialized disciplines stirred a great interest among the students which

prompted the management of the School to make the decision

to organize language classes in a different manner in order to

meet the needs of the students more efficiently. Starting with the

school year of 2013/14, students of each study programme attend English language classes separately from other groups, and

Business English course materials are combined with materials

from each specific field. This has already proven to be a good

practice, as the students invest more in learning what they will

actually be able to apply in their future professional lives.

However, as argued in the previous sections of this paper,

these ESP courses could be made more efficient through collaboration with subject specialists. To exemplify this notion, we

will outline a hybrid course of ESP for Computer Programming

in the framework of the Computing and Informatics curriculum. The teacher of Computer Programming is an expert in their

field, but is not required to know English, particularly at the level

required for students; therefore, this cooperation would also

help them to improve their language competences. As English

language is closely tied to the specialized area of IT, collaboration among the faculty members could result in deeper learning.

According to Barrons collaborative method (1992), the

contribution of the subject specialist could be indispensable; at

the design stage, they may suggest topics to be covered in ESP

class and help design needs analysis, while during the course

they may give tutorials or lectures, hold discussions, provide

assistance in writing or help to assess the students performance

on a project. The crucial point in this collaboration is that the

subject specialist determines the content, while the ESP teacher

works on the underlying concepts and skills. The IT science is

changing rapidly, with numerous parts, applications and processes developed on an almost daily basis. Therefore, the subject

specialist could help with the increased awareness of the texts

and areas to be included into the course materials. For example,

several IT course books frequently mention floppy disks that

were widely used several years ago, but are not used by modern

computers today.

The fact that classes for the students of Computing and Informatics usually take place at the Computer Laboratories could

additionally facilitate the teaching and learning process, as the

teachers could show the described processes and features to

students in practice, and the students and both teachers could

participate in joint studies and Internet searches. The role of the

English language teacher is to explain the structure and meaning of linguistic units in English (words, phrases, clauses and

sentences), and the role of the Programming teacher would be

to clarify the meaning of particular words (vocabulary) in order

to avoid semantic differences that need to be explained by both

correct use of the vocabulary from the lexicon, and the use of

that vocabulary in language structures.

Language for specific purposes (LSP) SYNTHESIS 2015

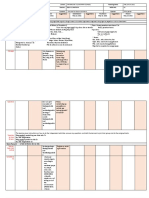

The application of Barrons third model (1992), the intervention, is realized in the virtual learning environment where

the language and the content are interwoven. In addition, by

applying the principles of Content and Language Integrated

Learning (CLIL), where the content is delivered in the foreign

language, the virtual classroom changes the dynamics of the

course into one which is learner-centered, constructivist and

motivating, as it prompts learners to use the language authentically to access information, gain understanding and formulate

new content knowledge (Ting, 2010). Additionally, the CLIL

research suggests that providing curriculum content in a second

or foreign language can lead to the enhanced L2 proficiency in

the academic faculty (Brinton &Snow, 1990). The synergy between the content and the language is embodied in the virtual

classroom which creates a simulated reality for the language use

in the context of the discipline (Fig. 1). The language, as well as

the ESP teacher, depends entirely on the content component of

this ensemble.

Fig. 1: How language and content intertwine

The hybrid model gives both teachers the extension of the

structured learning time as well as the opportunity to plan more

collaborative project or task based learning activities (Bonakdarian at al., 2010). For the purpose of this paper, we will follow Friends concept of hybrid learning as a course that

uses both in person and online instruction modes whatever

delivery mode is most appropriate for whatever task needs to

be accomplished (2013).

The winning game plan in this model course lies in the combined learning outcomes for the online component, which cover language, content, and learning goals (Fig. 2). The activities

and assignments in the virtual classroom reflect the combined

learning outcomes. Hence, the areas of assessment are aligned

to fit them both (Marsh, 2002):

Achievement of content and language goals

Achievement of learning skills goals

Use of language for various purposes

Ability to work with authentic materials

Level of engagement

Partner and group work

Fig. 2 Combined learning outcomes for the online component

of the course

DOI: 10.15308/Synthesis-2015-763-767

765

SYNTHESIS 2015 Language for specific purposes (LSP)

The aforementioned strategies are obviously less problematic in teaching the Computing and Informatics students.

However, they are applicable to other study programs, in which

ESP teachers are working on adjusting teaching materials and

combining texts from the field of Business English with texts

specializing in the primary disciplines. Successful teaching and

learning process regarding the curriculum that gets more and

more complex with every school year, requires interdisciplinary

team effort, as well as students hard work, as the most important objective of this process is for them to acquire academic

and professional competences they could afterwards effectively

implement in their professional practice.

5. ROADBLOCKS AND HOW TO OUTFLANK

THEM

The surveyed authors all agree that team teaching requires

great effort and time invested by the teachers. Tension and conflicts are not rare, so the challenge is to turn the table and use

the conflict as a learning opportunity (Buckley, 2000). Dinitz

et al. believe that our academic and professional development,

our experiences, our habits and beliefs make us ill-equipped

for sharing a classroom (1997). We are used to being in control and successful in our practice, whereas team teaching disturbs all that. Stewart and Perry insist on reflection being an

integral part of the teaching practice, team-teaching even more

so (2005). Admittedly, they also suggest that our assumptions

about teaching and learning often remain tacit mostly because

we are used to being enclosed in our own discipline and we

may lack the words to justify what we do. Finally, the issue of

increased workload for already overworked teachers who lead

busy lives is a tall obstacle.

In conclusion, or as a solution, this issue of the specialist

competences of the ESP teacher can begin to be resolved with

the model we proposed. However, this model is not sustainable

due to the reasons described above and eventually, ESP teachers will be on their own again. The next road sign for the poor

ESP teacher comes from Anthony who advocates that teachers

should assume the role of students in the ESP design, learning from the consulting specialists and the students themselves

(2007). In the first place, team-teaching practice can be a form

of teacher development programme (Stewart & Perry, 2005).

Secondly, with language learners now assuming the role of experts in a particular field, their motivation and contribution will

boost. In the end, that is the common goal the interdisciplinary

faculty should work toward.

6. SUMMARY

766

The paper tackles the issue of ESP course design for the

tertiary education; more specifically, it explores the role and

significance of content or professional knowledge of the ESP

teacher in the design process. The general goal of the paper is

to advocate professional and language competences as a means

of boosting employability and mobility of students. In addition, the specific aim of the paper is to present a combination

of teaching methods to overcome the aforementioned issues in

the course design.

Firstly, the paper outlines the problem of ESP course design

and defines the term teacher content knowledge as the pivot

point. Secondly, it reviews relevant theory and research literature supporting the strategy of interdisciplinary team teaching

in ESP courses for university students. Finally, it specifies the

models of team teaching that the authors base their proposal on.

DOI: 10.15308/Synthesis-2015-763-767

In the main part of the text, the authors propose a hybrid

course of English for Computer Programming to be delivered

at the Business School of Applied Studies in Blace. The ESP

course infers that a subject specialist works together with the

ESP teacher to plan and deliver the learning activities both faceto-face and online in the virtual classroom. In the first learning

environment, the subject specialist has the role of an informant,

while in the virtual learning environment, the teaching team

works side-by-side instructing and evaluating students. The

online component of the course unifies language and content

through CLIL approach and combined learning outcomes.

Instead of the conclusion, the paper directs attention towards the disadvantages of the interdisciplinary team teaching strategy and the issues in the sustainability of the proposed

model. However, the authors recommend that the model ESP

course should be just the initial step in achieving the more permanent solution.

REFERENCES

Anthony, L. (2007). The teacher as student in ESP course design.

Keynote address presented at the 2007 International Symposium on ESP & Its Applications in Nursing and Medical

English Education. Kaohsiung, Taiwan: Fooyin University.

Barron, C. (1992). Cultural Syntonicity: Co-operative Relationships between the ESP Unit and Other Departments. Hong

Kong Papers in Linguistics and Language Learning, 15, 2-15.

Bell, D. (2002). Help! Ive been asked to teach a class on ESP.

IATEFL Newsletter, No. 169.

Bess, J.L., & Associates (2000). Teaching alone teaching together.

San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Bonakdarian, E., Whittaker, T., & Yang, Y. (2010). Mixing it up:

more experiments in hybrid learning. Journal of Computing

Sciences in Colleges, 25(4), 97-103.

Brinton, D., & Snow, M.A. (1990). Content-based Language Instruction. New York: Newbury House.

Buckley, F.J. (2000). Team Teaching: What, Why and How. California: Sage Publications Inc.

Communiqu of the Conference of European Ministers Responsible for Higher Education (2009). Leuven and Louvain-laNeuve. Retrieved February 20, 2015, from http://europa.eu/

rapid/press-release_IP-09-675_en.html

Conderman, G. & McCarty, B. (2003). Shared Insights from University Co-Teaching.Academic Exchange Quarterly Winter,

7(4), 23-27.

Dinitz, S., Drake, J., Gedeon, S., Kiedaisch, J., &Mehrtens, C.

(1997). The Odd Couples: Interdisciplinary Team Teaching. Language and Learning Across the Disciplines, 2(2):

29-42.

Dudley-Evans, T. (1998). Developments in English for Specific

Purposes: A multi- disciplinary approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fenollera, M., Lorenzo, J., Goicoechea, I., & Badoui, A. (2012).

Interdisciplinary Team Teaching. In B. Katalinic (Ed.)

DAAAM International Scientific Book 2012, pp. 585-600.

Austria: DAAAM International.

Friend, C.R. (2013). On Vocabulary: Blended Learning vs.

Hybrid Pedagogy [Web log post]. Thinking Allowed. Retrieved February 20, 2015, from http://chrisfriend.us/Blog/

files/blended-vs-hybrid.php

Grska-Porcka, B. (2013). The role of teacher knowledge in ESP

course design. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rethoric,

34(47), 27-42.

Kaur, S. (2007). ESP course design: Matching learner needs to

aims. ESP World, 1(14), 6.

Leavitt, M.C. (2006). Team Teaching: Benefits and Challenges.

Speaking of Teaching, 16(1).

Little, A. &Hoel, A. (2011). Interdisciplinary Team Teaching: An

Effective Method to Transform Student Attitudes. The Journal of Effective Teaching, 11(1), 36-44.

Marsh, D. (2002). CLIL/EMILE The European Dimension. Actions, Trends and Foresight Potential. Strasbourg: European

Commission.

Nunan, D. (1987). The Teacher as Curriculum Developer: An

Investigation of Curriculum Processes within the Adult Migrant Education Program. Adelaide: National Curriculum

Resource Centre.

Language for specific purposes (LSP) SYNTHESIS 2015

Selinker, L. (1979). On the use of informants in discourse analysis

and language for specialized purposes. International Review

of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 17 (3), 189215.

Stewart, T., & Perry, B. (2005). Interdisciplinary Team Teaching

as a Model for Teacher Development. TESL-EJ, 9(2), 1-17.

Ting, Y.L.T. (2010). CLIL Appeals to How the Brain Likes Its

Information: Examples From CLIL-(Neuro)Science. International CLIL Research Journal, 1(3), 3-18.

767

DOI: 10.15308/Synthesis-2015-763-767

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- 2021 01 PPB 10 PuniaDokument14 Seiten2021 01 PPB 10 PuniaNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design and Validation of An Instrument To Measure Teacher Training Profiles in Information and Communication TechnologiesDokument24 SeitenDesign and Validation of An Instrument To Measure Teacher Training Profiles in Information and Communication TechnologiesNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Validation Evidence of The Motivation For Teaching Scale in Secondary EducationDokument12 SeitenValidation Evidence of The Motivation For Teaching Scale in Secondary EducationNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Exams (2015 - 2021) LanguageDokument15 SeitenNational Exams (2015 - 2021) LanguageNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ticket To English All Units PDFDokument98 SeitenTicket To English All Units PDFNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developing and Validating An EFL Teacher Professional Identity Inventory: A Mixed Methods StudyDokument18 SeitenDeveloping and Validating An EFL Teacher Professional Identity Inventory: A Mixed Methods StudyNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development and Validation of A Questionnaire To Evaluate Teacher Training For InclusionDokument10 SeitenDevelopment and Validation of A Questionnaire To Evaluate Teacher Training For InclusionNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Developmental Approach To The Use of Critical Thinking Skills in Writing: The Case of Moroccan EFL University StudentsDokument15 SeitenA Developmental Approach To The Use of Critical Thinking Skills in Writing: The Case of Moroccan EFL University StudentsNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- E685 PDFDokument19 SeitenE685 PDFNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Volume.7 Number.2 June, 2016 Pp. 457-467Dokument11 SeitenArab World English Journal (AWEJ) Volume.7 Number.2 June, 2016 Pp. 457-467Nasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching and Assessing 21st Century Critical Thinking Skills in Morocco: A Case StudyDokument21 SeitenTeaching and Assessing 21st Century Critical Thinking Skills in Morocco: A Case StudyNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- All UnitsDokument96 SeitenAll UnitsNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gate Way 1 Lesson Plans First Year BaccaDokument58 SeitenGate Way 1 Lesson Plans First Year BaccaNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Thinking Development: The Case of The English Course in The CPGE Classes in Meknes, Fes and KenitraDokument22 SeitenCritical Thinking Development: The Case of The English Course in The CPGE Classes in Meknes, Fes and KenitraNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- C Martix For Desigining A MethodDokument1 SeiteC Martix For Desigining A MethodNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- This Content Downloaded From 196.200.131.104 On Sat, 16 Oct 2021 09:30:03 UTCDokument11 SeitenThis Content Downloaded From 196.200.131.104 On Sat, 16 Oct 2021 09:30:03 UTCNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 70 (2020) 101164Dokument10 SeitenJournal of Applied Developmental Psychology 70 (2020) 101164Nasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- A. Look at The Pictures and Match Them With The Partitive NounsDokument3 SeitenA. Look at The Pictures and Match Them With The Partitive NounsNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- English For Specific Purposes: Role of Learners, Teachers and Teaching MethodologiesDokument18 SeitenEnglish For Specific Purposes: Role of Learners, Teachers and Teaching MethodologiesNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- This Content Downloaded From 196.200.131.104 On Sat, 16 Oct 2021 09:31:05 UTCDokument39 SeitenThis Content Downloaded From 196.200.131.104 On Sat, 16 Oct 2021 09:31:05 UTCNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Them All To University, But As Things Were, It Wouldn't Have Been PossibleDokument3 SeitenThem All To University, But As Things Were, It Wouldn't Have Been PossibleNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adverbs of Frequency Questions Esl Grammar WorksheetDokument2 SeitenAdverbs of Frequency Questions Esl Grammar WorksheetTrang Thương91% (22)

- Farid Enters The Scene Looking at The Ground As If He Had Lost SomethingDokument3 SeitenFarid Enters The Scene Looking at The Ground As If He Had Lost SomethingNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classroom Language WorksheetDokument1 SeiteClassroom Language WorksheetNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classroom Rules Commands Exercise With AnswersDokument2 SeitenClassroom Rules Commands Exercise With AnswersNasr-edineOuahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Brain Based Teaching StrategiesDokument19 SeitenBrain Based Teaching StrategiesAnaly BacalucosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ocr Media Studies Coursework Grade BoundariesDokument5 SeitenOcr Media Studies Coursework Grade Boundariesfzdpofajd100% (2)

- Iqra' Grade - One Curriculum Islamic Social Studies: Tasneema GhaziDokument17 SeitenIqra' Grade - One Curriculum Islamic Social Studies: Tasneema Ghazisurat talbiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 1 Hindi Lesson Plan 30th Oct - 7th Nov PDFDokument4 SeitenGrade 1 Hindi Lesson Plan 30th Oct - 7th Nov PDFSumayya14387% (31)

- A Project Report On Foreign Exchange: RelianceDokument4 SeitenA Project Report On Foreign Exchange: RelianceMOHAMMED KHAYYUMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Speaking Topics Lv4 Summer2023.Half1Dokument4 SeitenSpeaking Topics Lv4 Summer2023.Half1Thiện Nguyễn NhưNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effective Methods To Improving Reading Skills in English StudyDokument1 SeiteEffective Methods To Improving Reading Skills in English StudyLutfina Fajrin BudiartiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Profved Activity 1Dokument3 SeitenProfved Activity 1Jesel QuinorNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Language Teaching and Learning StrategyDokument5 SeitenEnglish Language Teaching and Learning StrategyDella Zalfia angrainiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Collins Offoha Resume 2Dokument3 SeitenCollins Offoha Resume 2api-269165031Noch keine Bewertungen

- TTL MODULE-2-Lesson-2Dokument6 SeitenTTL MODULE-2-Lesson-2Adora Paula M BangayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region XII Cotabato Division Aleosan East District Aleosan, CotabatoDokument4 SeitenRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Region XII Cotabato Division Aleosan East District Aleosan, CotabatofemjoannesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment Validation: Memory Matrix - by Group 3Dokument7 SeitenAssessment Validation: Memory Matrix - by Group 3vienna lee tampusNoch keine Bewertungen

- SANTOYA DELY For Demo..contextualized DLL. WEEK 32. COT2Dokument8 SeitenSANTOYA DELY For Demo..contextualized DLL. WEEK 32. COT2Jackie Lou ElviniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sílabo English VIDokument7 SeitenSílabo English VIAndres RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- B - Nani - Reflection - Introduction To LinguisticsDokument2 SeitenB - Nani - Reflection - Introduction To LinguisticsMildha DjamuliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 7 1ST Quarter Weekly Learning PlanDokument17 SeitenGrade 7 1ST Quarter Weekly Learning PlanAyesha CampomanesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lucas Perez ResumeDokument1 SeiteLucas Perez Resumeapi-534636127Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2013-14 FBISD HS Program GuideDokument47 Seiten2013-14 FBISD HS Program Guideclementscounsel8725Noch keine Bewertungen

- Visual Inquiry Lesson: Pontiac's RebellionDokument3 SeitenVisual Inquiry Lesson: Pontiac's RebellionNicole McIntyreNoch keine Bewertungen

- 16d85 16 - 2938 - Development of EducationDokument11 Seiten16d85 16 - 2938 - Development of Educationsunainarao201Noch keine Bewertungen

- PSL I PSL II Early Childhood Education Lesson PlanDokument6 SeitenPSL I PSL II Early Childhood Education Lesson Planapi-410335170Noch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluation of Internship Assessment in Medical ColDokument5 SeitenEvaluation of Internship Assessment in Medical ColawesomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- English 5.Q4.W5.Writing Paragraphs Showing Problem-Solution RelationshipsDokument13 SeitenEnglish 5.Q4.W5.Writing Paragraphs Showing Problem-Solution RelationshipsLovely Venia Joven100% (2)

- ORGA Syllabus DR AbrenicaDokument5 SeitenORGA Syllabus DR AbrenicaYaj CruzadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Workplan in Project KalingaDokument2 SeitenWorkplan in Project KalingaJholeen Mendoza Alegro-Ordoño100% (1)

- Unofficial TranscriptDokument4 SeitenUnofficial Transcriptapi-346386780Noch keine Bewertungen

- DRL Math 3 4Dokument6 SeitenDRL Math 3 4Joy CabilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- QA TeamDokument2 SeitenQA TeamRigino MacunayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 3 Content & PedagogyDokument5 SeitenModule 3 Content & PedagogyErika AguilarNoch keine Bewertungen