Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Physical Education at The Bauhaus 1919 33

Hochgeladen von

Kata PaliczOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Physical Education at The Bauhaus 1919 33

Hochgeladen von

Kata PaliczCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The International Journal of the History of Sport

ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20

Physical education at the Bauhaus, 1919-33

Swantje Scharenberg

To cite this article: Swantje Scharenberg (2003) Physical education at the Bauhaus,

1919-33, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 20:3, 115-127, DOI:

10.1080/09523360412331305813

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523360412331305813

Published online: 08 Sep 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 124

View related articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fhsp20

Download by: [Universitetbiblioteket I Trondheim NTNU]

Date: 27 October 2016, At: 08:24

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

15:37

Page 115

Physical Education at the Bauhaus,

191933

SWA N T JE S C H ARENBERG

The bauhaus was founded by Walter Gropius in April 1919 and became, in

the following years, one of the leading arts and crafts centres in Europe. One

reason for this was the equal importance given to architecture, art, sculpture

and crafts as well as industrial work. This idea of an integrated whole, fixed

in the human being itself, acquires sense and meaning only through vivid

life.1 The other reason was the international approach. Gropius derived the

inspiration for the idea and building of the Bauhaus from Ruskin and Morris

of England, Van de Velde of Belgium and the German Werkbund, which

consciously looked for and found initial ways to reunite the world of work

with that of creative artists.2 The staff was recruited from all over the world

and included such avant-garde artists as Johannes Itten from Switzerland,

the German-American Lyonel Feininger, the Russian Wassily Kandinsky

and the Hungarian Lzl Moholy-Nagy. They brought with them different

cultural and political ideas, which slowly coalesced to form a unique

project, sometimes even described as an order. Until 1933, when this place

of learning3 had to be closed down under pressure from the National

Socialists, this school was attended by eager young people from all over

Europe. Some of them were already adherents of either the Lebensreform or

the German Youth movement, two state-independent movements which

strove for a healthy community and a renewed culture as a reaction to rising

technology, while demanding a return to the body4 as the core of their

physical and philosophical ideals.5

Gropius aim was to create a sustainable relationship between work and

life. Today it is impossible to reform just one partial object, we have to take

a good look at the entirety of life itself: housing, the education of children,

gymnastics and much more.6 For this purpose he asked outstanding

protagonists to join his school where the final programme was the idea of

objective teaching. Gropius was convinced that the objective method of

teaching, even if the way to this is much longer and more thorny than the

autocratic method, not only safeguards us from imitation and

egalitarianism, it protects the uniqueness in every creative personality and

simultaneously promotes the common spiritual coherence of the times.7

This very open situation stimulated people to contribute their own ideas, if

The International Journal of the History of Sport, Vol.20, No.3 (September 2003), pp.115127

PUBLISHED BY FRANK CASS, LONDON

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

116

15:37

Page 116

THE I NTERNATI ONAL J OURN A L O F T H E H I S TO RY O F S P O RT

only for a certain amount of time. Physical education at the Bauhaus was

always the personal preference of the leading individuals that determined

the syllabus, which included artistic gymnastics as well as dance and sports

in logical sequences.

The aim of this paper is to show that physical education at the Bauhaus

was used

1. to experience the space, rhythms and movements of the body and to

integrate these feelings into the students artistic expressions,

2. to heal neuroses through physical activities which followed certain rules

and regulations suitable to creating a community spirit,

3. to model art on bodily movements by looking for the essence at the heart

of both.

Johannes Itten and his Preparatory Course

The Swiss painter, Johannes Itten, was one of the first teachers at the

Bauhaus. When he started his work in autumn 1919 his main contribution

was to introduce a compulsory preparatory course, which adopted an

integrated approach. As a convinced reforming educator he did not want to

create a special school or to intrude on the personality of his students, but

he had absolute respect for the individuality of the learner8 and wanted to

foster hidden talents. Itten, apart from his artistic talents, had himself been

a successful competitive artistic gymnast. He also played soccer, did track

and field and played the piano. In the course of his own studies he tried to

combine all these different activities, and from 1913 his teacher Adolf

Hlzel encouraged him to do so. Hlzel himself did not start working until

he had completed 100 tuning-up exercises, like a violin player.9

Ittens idea from the very start of Bauhaus education was more

sophisticated. Following Platos idea of the three aspects of education

gymnos (physical education), arts (especially music) and mathematics

(education designed to encourage constructive, logical thinking) he

developed a training system that was suited to the individual character both

intuitively and objectively. It revealed the technical possibilities implicit in

disregarding the rules of form and colour in art, and developed them to

perfection in the realization of individual ideas.10

All he wanted to achieve with the preparatory course was to develop an

instrument to promote the talents of the student, to let the learner find his or

her own form of self expression and to select people for special training.

Itten, a trained primary school teacher, considered the human being in itself

to be his pedagogic responsibility, a nature to be encouraged and developed:

an evolution of the senses, an increase in the ability to think and to

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

15:37

Page 117

PHYS ICAL EDUCATI ON AT THE BAUHA U S , 1 9 1 9 1 9 3 3

117

experience both a form of relaxation11 and a training for the organs

and their functions these are the methods a pedagogically responsible

teacher uses.12

Both Gropius and Itten did not want students to specialize early, but

rather to have a solid base for their chosen arts and crafts. With this

introductory course he developed a trans-individual language of form

especially for the Bauhaus.13

Itten integrated sport into this course foremost as a means of physical

control.

First of all the artist and craftsman has to control his body in such a

way that he follows each change of the mind. His hand must be agile,

relaxed, firm and yet smooth, rapid and yet careful, well-shaped and

strong, his arm, in fact his whole body has to be trained in such a way

that every muscle, every ligament is subject to his will. Thus the

student will very easily learn what it means to work with his hands.14

What sounds like Pierre de Coubertins gymnastique utilitaire, which was

used directly to achieve those skills required by new technology but which

also wanted people to do crafts as mental health training,15 is, actually, quite

different. Ittens idea was not to adapt the human being to technology, but

rather to bend the body to the will of the soul. He complained that artistic

gymnastics exercises were bereft of content and mindless, as if we do

artistic gymnastics only for the sake of artistic gymnastics and to improve

our muscles. According to his definition, artistic gymnastics was a part of

gymnastics, but was not able to give the body expressiveness, experience,

was not able to arouse these feelings in the body.16 Usually Itten started his

lessons with gymnastic exercises, to experience, to feel, to unleash frantic

movements, to shake the body. Then exercises stressing harmony follow.17

The training of harmonization focused on rhythm and breath18 and

should develop from flow and order, from equilibrium and coordination

through as the painter Paul Klee put it body massage. Klee interpreted

Ittens individual posture control of each student, and his method of

ordering the students to develop a certain rhythm, as training a machine to

function instinctively.19 In this part of the course Itten wanted his students

to free themselves mentally and to find their individual rhythm as a

subjective aspect, but also recognize objectively that rhythm is a

fundamental principle.20 Physically they should, for example, draw with

both hands at the same time to compensate for the lack of skilfulness of the

left hand.

This preparatory course already put into practice what the Austrian

reform educator Margarethe Streicher would write three years later:

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

118

15:37

Page 118

THE I NTERNATI ONAL J OURN A L O F T H E H I S TO RY O F S P O RT

To feel and experience ones own body as a spatial object, initiating a

movement, the sequence of actions of different muscle groups, the use

of gravity and swing, the correlation between breathing and

movement, things which are in many cases still regarded as

insignificant and irrelevant today. That each movement structures

space, and therefore is an admittedly transient work of art, and that it

also structures time, and is therefore at the same time a work of music

for some this sounds like discovery and for others, madness. This

different assessment clearly shows how little known and how little

understood rules of movement still are today.21

From the very start, Ittens main interest was to find out how form

emerges from movement. He viewed the coherence of movement and form

as identity and stressed the emotional more than the intellectual.22

All life reveals itself to the human being by means of movement. All

life reveals itself in forms. So all forms are movement and obviously

all movement, form. The forms are receptacles of movement and

movement the nature of form Every spot, every line, area, every

shadow, every light and every colour are forms originating from

movement, which will again in turn originate movement If I want

to experience a line, I have to move my hand corresponding to the

line, or I have to follow the line with my senses, thus moving my

spirit. Finally I can imagine a line mentally, I can see it, then I am

mentally moved. So these are three different levels of being moved

In front of me there is a thistle. My motor nerves feel a jagged, rapid

movement. My senses, the sense of touch and face, grasp the sharp

pointiness of its form, and my mind sees its nature It is obvious that

I can draw a proper thistle only if the movement of my hand, my eyes

and my mind correspond exactly to the intense pointed, pricking,

painful form of a thistle: which means character of movement equals

character of form. This is the main statement of our whole research.23

Today Ittens preference for gymnastics is often explained by his

conversion to Mazdaznan,24 a Far Eastern doctrine of salvation. The reason

for this is that one cannot find a difference between the philosophy of

Mazdaznan and anthroposophic philosophy as well as expressionism. All

three focused on the individual, on the whole picture, and above all on

morals. And these morals again and again lead to the integrated educated

human being, therefore far over and above the one dimensional educated

craftsman.25

The return to the body and the individual no longer played a major role

when Itten left the Bauhaus in Spring 1923. The preparatory course now

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

15:37

Page 119

PHYS ICAL EDUCATI ON AT THE BAUHA U S , 1 9 1 9 1 9 3 3

119

focused on technology. In 192324 there were no gymnastics on the

syllabus. The crafts and work done by hand as well as the individual

training of personality, which were so important for Ittens teaching

concept, lost their meaning.26 The founding phase of the Bauhaus was over,27

and a negative opinion was held about the way art and muscles interact; in

the Bauhaus magazine of 1928 it was observed that neither sport nor

technology stimulates contemporary art creatively.28

Introducing Sport

In 1928 one of the most important functionalists in 1920s architecture,

Hannes Meyer, became director of the Bauhaus, now situated in Dessau.

The newly-built school, with a gymnasium and a playing field, had already

been planned when Gropius was still the principal (in 1925). He regarded

the gym, as well as the flat roof stable enough also to be used for

workouts29 as welfare facilities, that is, facilities for the good of the

students.30 In earlier years Bauhaus students, accompanied by their director

Gropius, had often gone for a bath in the Elbe River in their leisure time.

Hannes Meyer thought differently and introduced sports and sciences,

such as physics and chemistry, into the syllabus. He regarded a university

without physical exercise as an absurdity, and used the introduction of

sport to combat the proverbial collective neuroses of the Bauhaus, the

result of a one-sided emphasis on brainwork.31 Now Saturday was devoted

to sports,32 and Meyer employed two physical education teachers: Otto

Bttner was responsible for mens sport and mens gymnastics, while Carla

Grosch was in charge of physical education for women. In 1929 Meyer even

requested public funds (2,000 marks) to improve the ground conditions of

the playing field.33 Under the headline Life at the Bauhaus some

photographs show us what the sport was like.34 Otto Bttner taught track and

field and used to take an active part in his lessons by demonstrating the

correct techniques. Carla Grosch was also a very active instructor, and

taught the girls gymnastics all year round, mostly outside on the flat roof,

because sun and light played an important role in the ideology of the

Bauhaus. Even in wintertime when the temperature was five degrees below

zero, young female weavers went outside dressed in tops and shorts to work

out with medicine balls.

Hannes Meyer regarded the Bauhaus as a social phenomenon and saw

the final aim of all the work of the Bauhaus to be the summation of all life

forces to promote a harmonious form of society.35 Art itself could be used

as an instrument of cultural and social regeneration.36 Meyer promoted the

idea of sport because it mirrors a sense of community with well-established

rules and regulations. In his essay The New World, a cultural programme

for a developing society, which stressed that valuable new characteristics

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

120

15:37

Page 120

THE I NTERNATI ONAL J OURN A L O F T H E H I S TO RY O F S P O RT

are shaped by the rapid progress of science and technology,37 he confronted

art with sport.

G. Paluccas dances, von Labans movement ensembles and D.

Mensendiecks functional gymnastics (Turnen) are driving out the

aesthetic eroticism of the nude in painting. The stadium has carried

the day against the art museum and physical reality has taken the place

of beautiful illusion. Sport merges the individual into the mass. Sport

is becoming the university of collective feeling: Suzanne Lenglens

cancellation of a match disappoints hundreds of thousands.38

Breitenstrters defeat sends a shiver through hundreds of thousands.

Hundreds of thousands follow Nurmis race over 10,000 metres on the

running track The community rules the individual. Each age

demands its own form The demands we make on life today are all

of the same nature depending on social stratification. The surest sign

of true community is the satisfaction of the same needs by the same

means The degree of our standardization is an index of our

communal productive system The revolution in our attitude of

mind to the reorganization of our world calls for a change in our

media of expression Instead of the static imitation of movement in

sculpture, we have movement itself (synchronized film, illuminated

advertising, gymnastics, eurhythmics, dancing) The art of felt

imitation is in the process of being dismantled. Art is becoming

invention and controlled reality. Art is becoming reality.39

In the organizational scheme that he designed for the Bauhaus, he

considered sports, the stage and the Bauhaus orchestra to be a unit with

three study-groups, but only sport was taught by specialists. Carla Grosch,40

the physical education teacher, was the new woman who became a public

advertisement for the Bauhaus,41 where women were not only allowed to

study but also to teach. Grosch had an athletic figure, short hair and a certain

charisma. She was very much in love with life, the link between sport and

art, between the teacher and the Bauhaus actor or scholar. She had been in

contact with people from the Bauhaus since 1922, especially with the Klee

family. Trained at the school of Gret Palucca in Dresden,42 she was not only

a teacher of gymnastics and physical education but also took part in the

work of the stage department led by Oscar Schlemmer. While Palucca

taught her to discover individual creativity through dance, to react

according to the rhythm of her own body43 and actively to determine space

and music, Schlemmer focused on precision of movement, the human being

as a biomechanical machine, involving rules for functioning right up to the

dematerialization of the standardized body into movements and

expressions, which acquire a symbolic character.44 As Oskar Bie put it: The

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

15:37

Page 121

PHYS ICAL EDUCATI ON AT THE BAUHA U S , 1 9 1 9 1 9 3 3

121

Bauhaus stage has discovered its special mission. It is called: the art of

movement in relationship to the pure expression of space and the pure

expression of material, the integration of human rhythm into a rhythm of

absolute structure.45

In 1928 and 1929 Grosch participated in different dance presentations.46

She also presented a work, which she created with Albert Menzel, called

colour dance where she started to dance in front of a white illuminated

square wall, which was brightened by horizontal colour projections during

her performance.47 This central focus on a woman who, in public, was able

on the one hand to act with her body under total control and, on the other,

to deliberately lose control of her body in space thus demonstrating other

possible forms of movement, proved that it was possible for women to act

according to their own ideas, in some areas at least, and therefore

strengthened the position of power of women in society.48

Looking for the Nucleus of Movement and Art

After World War I the threat of an approaching formlessness seemed to

spread throughout Europe. The regrettable situation was that the modern

human being no longer had any real feeling for his body and therefore he

also had no feeling for a common (social) form, and vice-versa.

Educationalists and artists thought the solution to this lack of orientation

could be found in building up a form from the inside49 by searching for the

nucleus of the human being. Margarethe Streicher50 based her theory on the

regular rhythm of the body, whatever work it undertakes. Therefore the

validity of all physical work is actually a standard for defining the accuracy

of physical rules.51 In order for physical exercises to be accepted as a

general means of education by broad sections of the population, the

principles of artistic physical education and of (artistic) gymnastics have to

be adapted to each other. This is possible if there is no longer a

differentiation between exchanging knowledge and educating the whole

human being. The task of the teacher of science as well as of gymnastics is

the same: to facilitate the best development of the power and talents of a

child, which is also the best preparation for work Physical work and

therefore physical education are also necessities of life.52

The basis of good physical education is knowledge of the body you want

to educate. Therefore Streicher suggested that instead of copying exercises

mechanically, one should observe the movements several times.

To find pure movement the student has to let an impulse swing out

in his/her body without hindering it arbitrarily anywhere, only

allowing the interplay of his/her joints. If you listen to your body and

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

122

15:37

Page 122

THE I NTERNATI ONAL J OURN A L O F T H E H I S TO RY O F S P O RT

concentrate on its internal rules of form, you will experience physical

liberation. Thus all individual movements will turn into movements in

accordance with the law of the body, right and therefore beautiful.53

Released power, as well as talents that have been submerged, will now

become creative. The final step is to apply the individual realization of form

learned in physical education to life.54

Artists had to take a different approach from Streichers to build up their

bodies to their satisfaction, but they ended up with the same result: only

knowledge of the rules of the body and of the rules of nature can create art.55

After the Bauhaus artists had been shown what dance and sport are like, and

after they had gained a little physical education experience and its influence

on their own bodies, they became receptive to Paluccas new-found rule of

movement, the most precise structure of tension-filled living space, or, as

Lzl Moholy-Nagy put it: an elementary expression of physics in close

relationship with spatial dynamics no longer an expression of ritualistic,

sexual motives or an illustration of wonder.56 We ourselves swing in her

dance, move by using the power of her vitality and self-control. Palucca

condenses space, she structures it: space extends, sinks and floats

changing in all dimensions The tensions of space enter her body, occur

through her body, with incredibly natural body-mind unity. She is the purest

among the dancers of today.57 By looking at Palucca and her dancing, the

power of individual expression as art and the range of different ways of

presentation became obvious. The work of art, as it emerges from the

whole human being, represents this human being and has no other dynamics

than the dynamics of just these energies of its character and its condition.58

In expressive dance, form and content fused in a unique process, where the

audience became part of the art work,59 while all other art forms could only

show movements condensed into one moment.60 Palucca, for example,

was the first to select music according to its usefulness for her dance; music

interpreted by her very personally was only a means to implement her

own ideas. She wanted to be the active component that introduced ideas.

The wild jumps and expressive poses of Carla Grosch and Gret Palucca61

attracted Klee and Kandinsky, who were interested in translating them into

drawings. They used photographs taken by Charlotte Rudolph to transform

body tensions into geometric forms. Wassily Kandinsky especially saw the

artistic as more essential than the naturalistic62 and was so impressed by this

form of biomechanics that he asked Palucca to dance routines with circles

and triangles.63

The Bauhaus Magazine statement of 1928, that reason and movement,

those moments that determine sport, could better be recorded through the

photomechanics of a film camera than through the personal soul filter of an

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

15:37

Page 123

PHYS ICAL EDUCATI ON AT THE BAUHA U S , 1 9 1 9 1 9 3 3

123

artist,64 was no longer true. The expressionistic artist had broadened his

field of action by presenting the permanent tension between the inner and

the outside world. The concrete should not only be shown, but be visible,

nature no longer reproduced, but represented via art.65

Conclusion

The question of form, and therefore body, determined the work of the

Bauhaus from start to finish. Physical education played different roles

thereby. Physical exercises were used to train and prepare the body for the

subsequent art work. Following the ideas of the Bauhaus reform-minded

educators, the human being had to be given an integrated education. The

unifying power of sport was implemented to cure highly sensitive and

individualistic artists of their neuroses and to find, via sport, a new approach

to society and a living example where women, too, had an active role.

The body, seen as a focus for artistic as well as physical expression,

especially dance, was, however different the approach, another way to

unify a society facing the threat of a common lack of form. It took quite

some time for the people at the Bauhaus to realize that sport is more than a

matter of developing muscles but is also an art form and that art is a part of

physical education.

Deutscher Turner-Bund

NOTES

1. Walter Gropius, Idee und Aufbau des Staatlichen Bauhauses, in Walter Gropius (ed.),

Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar 19191923 (Weimar and Munich: Bauhaus-Verlag, 1923), p.9.

Walter Gropius, Die neue Bau-Gesinnung, quoted in Probst and Schdlich, Walter Gropius

(Werkverzeichnis Teil III: Probst, Hartmut Ernst-Verlag) (1925), p.96.

2. Gropius, Idee und Aufbau des Staatlichen Bauhauses, p.8. For the educational-historical

coherence of craftsmanship and pedagogical motive see Rainer Wick, bauhaus Pdagogik

(Kln: Dumont, 1982, 4. berarbeitete und aktualisierte Auflage 1994), p.67f.

3. Gerhard Marcks an das Staatliche Bauhaus, 2.1.1924, in K.-H. Hter, Das Bauhaus in

Weimar (Berlin, 1983), p.219.

4. See Michel Foucault, Mikrophysik der Macht. ber Strafjustiz, Psychiatrie und Medizin

(Berlin: Merre Verlag, 1976), p.105ff.

5. See Rolf Bothe, Peter Hahn and Hans Christoph von Tavel, Vorwort, in idem. (eds.), Das

frhe Bauhaus und Johannes Itten. Katalogbuch anllich des 75. Grndungsjubilums des

Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar (Ostfildern-Ruit, 1994), p.7. Thomas Alkemeyer, Krper,

Kultur, Politik. Von der Muskelreligion Pierre de Coubertins zur Inszenierung von Macht

in den Olympischen Spielen von 1936 (Frankfurt and New York: Campus-Verlag, 1996),

p.65f.

6. Letter from Walter Gropius to Eckhart (Adolf Behne) dated 2 June 1920. Quoted in W.

Nerdinger, Walter Gropius. Ausstellungskatalog Bauhaus-Archiv (Berlin: Gebr. Mann,

1985), p.58.

7. Walter Gropius, Die Bauhaus-Idee Kampf um neue Erziehungsgrundlagen, in Eckhard

Neumann (ed.), Bauhaus und Bauhusler: Erinnerungen und Bekenntnisse (Kln: Hallwag,

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

124

15:37

Page 124

THE I NTERNATI ONAL J OURN A L O F T H E H I S TO RY O F S P O RT

1985), p.17f., quotation p.18.

8. He had learned this principle during his time at the teachers training seminar in Bern.

9. See Carry van Biema, Farben und Formen als lebendige Krfte (Jena: Ravensburger

Buchverlag, 1930), p.130.

10. Johannes Itten, Mein Vorkurs am Bauhaus. Gestaltungs- und Formenlehre (Ravensburg:

Maier, 1963), p.10. Johannes Itten and Zur Ausstellung, Aus meinem Unterricht (Orell

Fssli, 1939), in Willy Rotzler (ed.), Johannes Itten. Werke und Schriften (Zurich: DuMont,

1978), p.244. Wick, bauhaus Pdagogik, p.120.

11.

Relaxation of the body can be achieved in three different ways: first through movements

of arms and legs, through bending and twisting of the whole body, while the mobility of

the spinal column has to be paid special attention. The second action is to keep the

standing, sitting or prostrate body absolutely still and to relax it through mental

concentration limb by limb. Only in this way can inner organs be relaxed. The third

possibility, to relax the body, to equalise and harmonise it, is to use tonal vibrations.

Firstly students have to train how to build a tone, they have to learn to feel where inside

their body the tones vibrate. (Johannes Itten, Mein Vorkurs am Bauhaus. Gestaltungs- und

Formenlehre [Ravensburg: Maier, 1963], p.12.)

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

Margarethe Streicher describes a wave of movement initiated by tension and relaxation:

Every human movement is achieved by working the muscles. But after the work has been

done the muscles have to return to zero tension, muscles natural state While relaxation

exercises help to learn how to differentiate grades of tension they also help to learn about

gravity. Comprehending a movement is like looking at pictures in art appreciation.

Margarethe Streicher, Was kann das Turnen von den modernen Systemen lernen? (Februar

1924), in Karl Gaulhofer and Margarethe Streicher, Natrliches Turnen. Gesammelte

Aufstze I (Vienna and Leipzig: Verlag Jugend und Volk, 1931), pp.10710, quotation p.109.

Johannes Itten, Pdagogische Fragmente einer Fomenlehre (1930), in Rotzler (ed.),

Johannes Itten. Werke und Schriften, p.232.

See Wick, bauhaus Pdagogik, p.35. Friedhelm Krll, Bauhaus 19191933. Knstler

zwischen Isolation und kollektiver Praxis (Dsseldorf: DuMont, 1974), p.55. Wick (p.20)

points out the basic conflict between free artistic self-expression on the one hand and the

search for a language of form, adequate to the needs of mass-production in a high-developed

industrial society on the other.

Johannes Itten, Kunst-Hand-Werk, quoted in Rotzler (ed.), Johannes Itten. Werke und

Schriften, pp.225 and 226.

See Alkemeyer, Krper, Kultur, Politik, p.112. There were other schools also which

combined physical education and arts and crafts, such as the Dresdener Werksttten fr

Handwerkskunst in Hellerau where from 1911 onwards Emile Jaques-Dalcroze pushed

forward the idea of an educational establishment of rhythm (Karl Storck, E. JaquesDalcroze. Seine Stellung und Aufgabe in unserer Zeit [Stuttgart, 1912], p.88), or the

Loheland school, see footnote 50.

Johannes Itten, Tagebuch X, 2.3.1918, in Eva Badura-Triska (ed.), Johannes Itten:

Tagebcher. Stuttgart 19131916; Vienna 19161919 (Vienna: Lckeer-Verlag, 1990, 2 vols)

p.387. Margarethe Streicher agreed with his opinion. She says that artistic gymnastics often do

not accept the form rules of the body but let forms of style determine forms of movement:

Streicher, Was kann das Turnen von den modernen Systemen lernen?, pp.10710, esp. p.108.

Itten, Tagebuch X, 2.3.1918, p.387. In 1919 Itten brought Gertrud Grunow to the Bauhaus.

She taught harmonization to rediscover the personal internal equilibrium of colours, tones,

sentiments and forms through exercises of movement and concentration. Itten and she

believed that only a harmonious human being could be creative. See Bauhaus archive and

Magdalena Droste (eds.), bauhaus 19191933 (Kln: Taschen, 1993), p.33.

Rhythm, especially, was seen as determining the being and was traced back to the periodic

function of the breath. Rudolf Lmmel, Der moderne Tanz (Berlin, 1928), p.16. If you listen

to your own rhythm you will become a harmonious person.

Description of Paul Klee 1921, in Felix Klee (ed.), Paul Klee. Briefe an die Familie

18931940 (Kln: DuMont, 1979), vol.2, p.970. For body and soul see Gabriele Klein,

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

15:37

Page 125

PHYS ICAL EDUCATI ON AT THE BAUHA U S , 1 9 1 9 1 9 3 3

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

125

FrauenKrperTanz. Eine Zivilisationsgeschichte des Tanzes (Weinheim and Berlin: Heyne,

1992), p.146.

See Rainer K. Wick, Zwischen Rationalitt und Spiritualitt Johannes Ittens Vorkurs am

Bauhaus, in Bothe, Hahn and von Tavel (eds.), Das frhe Bauhaus und Johannes Itten.,

pp.11767, esp. p.138f.

Margarethe Streicher, Zur Erneuerung der Tanzkunst (Juli 1922), in Gaulhofer and

Streicher, Natrliches Turnen. Gesammelte Aufstze, pp.2630, quotation p.29.

See Wick, bauhaus Pdagogik, p.104.

Johannes Itten, Analysen alter Meister (1921), in Rotzler (ed.), Johannes Itten. Werke und

Schriften, p.220ff.

Mazdaznan is a word of Zen language: Ma = good or God; zda = thought; znan

(abbreviated from jasnan) = masterly; all in all it means master of Gods thought or the

good thought, that all things masters to the best. Mazdaznan wants to be a guide, which is

originated by God and leads all need and disordered to a good, high aim. Kurt Hutten, Seher,

Grbler, Enthusiasten. Sekten und religise Sondergemeinschaften der Gegenwart (Stuttgart:

Quell Verlag, 1962), p.288. In Germany this doctrine of salvation was introduced by its

spiritual leader, Dr Otoman Zar-Adusht Hanish, in 1907. For his philosophy see Otoman ZarAdusht Hanish, Offenbarungen (Leipzig: Mazdazen, 1931).

Ludger Busch, Das Bauhaus und Mazdaznan, in Bothe, Hahn and von Tavel (eds.), Das

frhe Bauhaus und Johannes Itten, pp.8390, quotation p.85. Mazdaznan included a rigorous

diet and vegetarian food as well as ritual body exercises like breath control, movement and

relaxation exercises. After Itten visited a seminar of Mazdaznans in 1921 he introduced

vegetarian food at the Bauhaus.

See Bauhaus Archive and Droste, Bauhaus 19191933, p.46.

On the division into the three phases of foundation (191923), consolidation (192328) and

disintegration (192833), see Krll, Bauhaus 19191933.

Bauhaus 2 (1928), 4, 29.

See Walter Gropius, Bauhausbauten Dessau (Mainz and Berlin: Kupterberg, 1974), p.54.

The successful experiments, that were made with the construction of horizontal roofs to

walk or not to walk on in the past 20 years, convince me, that the technical advanced human

being will use flat roofs exclusively in the future for instance for living (as playgrounds,

or to dry clothes) (p.55).

Ibid., p.15.

Hannes Meyer, Mein Hinauswurf aus dem Bauhaus. Offener Brief an Herrn

Oberbrgermeister Hesse, Dessau, in Hannes Meyer, Das Tagebuch (Berlin, 33, Bauhaus,

1930), vol.2, p.1307ff.

While on Mondays there were only music lessons and on Fridays only science, from Tuesday

to Thursday students worked in the studios for the entire 8-hour day like industrial workers.

In the Dessau Bauhaus syllabus of 1927 (leaflet Bauhaus Dessau, 1927, pp.45) gymnastics

and dance (voluntarily) belong with the general subjects and are taught in the first semester

for approximately two to four hours, in the second semester approx. 2 hours exercises

(unspecified) are advertised for more advanced students, in the 3rd semester part of the

studio work (are) exercises of gymnastics, dance, music, language, to prepare for the stage

science in the following semesters. In the first syllabus under Mies van der Rohe (Sept.

1930), Otto Bttner and Carla Grosch were still mentioned as teachers for sport and

gymnastics.

Situationsbericht von Hannes Meyer, Dessau, 1 September 1929 in Werner

Kleinerschkamp, hannes meyer 18891954. architekt urbanist lehrer (Berlin and

Frankfurt am Main: Ernst, 1989), p.169.

Artists and Pictures: Lutz T. Feininger Sport am Bauhaus (c. 1927), Herbert Bayer Fahrrad

(1928), Hajo Rose Hochspringer vorm Prellerhaus (showing Otto Bttner) (1930),

anonymous Sprung von der Terasse der Bauhaus-Kantine (1930).

Hannes Meyer, Bauhaus und Gesellschaft, bauhaus 1 (1929), 2.

Wick, bauhaus Pdagogik, p.14.

Klaus-Jrgen Winkler, Kunst und Wissenschaft. Hannes Meyers programmatische Schrift

Die Neue Welt und die Wettbewerbsentwrfe Petersschule und Vlkerbundpalast, in

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

126

15:37

Page 126

THE I NTERNATI ONAL J OURN A L O F T H E H I S TO RY O F S P O RT

Kleinerschkamp, hannes meyer 18891954, pp.94108, quotation p.95.

38. See Susan Bandy, Suzanne Lenglen und das Knstlerische und Heroische im Sport, in Arnd

Krger and Bernd Wedemeyer (eds.), Aus Biographien Sportgeschichte lernen. Festschrift

zum 90. Geburtstag von Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Henze (Hoya: Nish, 2000), pp.16376.

39. Hannes Meyer, Die neue welt, Das Werk, 13 (1926), 7.

40. Carla Grosch was born in Weimar in 1904 and drowned in Tel Aviv in 1933.

41. Many of the traditional art academies did not want to allow women to study, in spite of the

regulations of the new Weimar constitution. So the Bauhaus was initially a forerunner, but in

1921 started to force women into the women classes, as the weaving mill was called. Anja

Baumhoff, Ich spalte den Menschen. Geschlechterkonzeptionen bei Johannes Itten, in

Bothe, Hahn and von Tavel (eds.), Das frhe Bauhaus und Johannes Itten, pp.919. For art

colleges and women: Walter Reimann, ber den Kampf der Frauen in Deutschland um

akademische Ausbildung auf dem Gebiet der bildenden Kunst, Studien zur Geschichte der

Hochschule fr bildende Knste Dresden (Dresden: Bauhaus, 1983), pp.1, 5ff. In general:

Barbara Duden and Hans Ebert, Die Anfnge des Frauenstudiums an der Technischen

Hochschule Berlin, in Reinhard Rhrup (ed.), Wissenschaft und Gesellschaft. Beitrge zur

Geschichte der Technischen Hochschule Berlin, 18791979 (Berlin: TV Berlin, 1979),

p.404.

42. Gret Palucca began teaching in 1924 and founded her school in 1925. She herself started to

do ballet at the age of 12, but realized that she could not express her own ideas. The 17-yearold Gret Palucca was deeply impressed by Mary Wigman: It was something incredibly new,

something so elementary that it immediately became clear to me: either I learn her way of

dancing now or I will never learn it. Here was the new dance, which matched my ideal here

was the human being and the role model I needed. Gerhard Schumann (ed.), Portrt einer

Knstlerin (Berlin: Bauhaus, 1972), p.174. Her intention was to form good craftswomen of

dance, because dance primarily involves technique and craftsmanship (Palucca ber ihre

Schule. Aus den Musikblttern des Anbruch 1926, in Tanz Palucca. Bilder,

Besprechungen und Auszge aus Kritiken von Solo- und Gruppen-Tanzauffhrungen 1926

and 27, p.27.) In the early years of the Third Reich, up to 1936 and the Olympic Games in

Berlin, she climbed the ladder of success. Under the guidance of Rudolf von Laban she was

the best-paid and leading educator of artistic dance and the most famous German dancer of

the time. See Peter Jarchow and Ralf Stabel, Palucca. Aus ihrem Leben ber ihre Kunst

(Berlin: Bauhaus, 1997), p.43.

43. See Jarchow and Stabel, Palucca. Aus ihrem Leben ber ihre Kunst, esp. pp.21 and 23.

44. See Die Neue Sammlung Munich (ed.), Oskar Schlemmer und die abstrakte Bhne. 20

November 1961 bis 8. Januar 1962. For Schlemmers lesson on the human being, which he

only taught for one year, because he left the Bauhaus in 1929, see Oskar Schlemmer,

bauhaus 23 (1928), 23. Andreas Bossmann, theaterreform lebensreform. ganzheitlichkeit

im knstlerischen schaffen oskar schlemmers, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen oskar

schlemmer. tanz theater bhne (Ostfildern-Ruit, 1994), pp.2230. Bauhaus Archiv and

Magdalena: Draste/Taschen bauhaus, 19191933, p.171.

45. Berliner Brsen-Courier 4.3.1929.

46. 7 July 1928: Maskentanz oder Tischgesellschaft, 1928 and 29: Drei gegen Eine; 1929

Glastanz and Metalltanz.

47. Dirk Scheper, Oskar Schlemmer Das Triadische Ballett und die Bauhausbhne (Berlin:

Bauhaus, 1988), p.175.

48. See Klein, FrauenKrperTanz. Eine Zivilisationsgeschichte des Tanzes, p.133.

49. Franz Marc quoted by Margarethe Streicher, Was kann das Turnen von den modernen

Systemen lernen? (Februar 1924), in Gaulhofer and Streicher, Natrliches Turnen.

Gesammelte Aufstze I, pp.10710, quotation p.107. For Hermann Nohl, the understanding

of art was dependant upon an as yet unachieved common acceptance of society. Hermann

Nohl, Die sthetische Wirklichkeit. Eine Einfhrung (Frankfurt am Main: Schullte-Bulmke,

1935), p.216.

50. Margarethe Streicher had studied the philosophy of Loheland. This private school for

agriculture, crafts and physical education (classical gymnastics), founded in 1912, had the

aim of developing a graduated physical consciousness in its students. Margarethe Streicher,

203sh07.qxd

04/09/03

15:37

Page 127

PHYS ICAL EDUCATI ON AT THE BAUHA U S , 1 9 1 9 1 9 3 3

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

127

Loheland (August 1922), in Gaulhofer and Streicher Natrliches Turnen. Gesammelte

Aufstze I, pp.3034. Margarethe Streicher, Zur Erneuerung der Tanzkunst (Juli 1922), in

ibid., pp.2630.

Margarethe Streicher, Die Bedeutung der krperlichen bungen fr die Erziehung (Januar

1923)in ibid., pp.3440, quotation p.40.

Ibid. There was already some co-operation between P.E. teachers and artists initiated by

physical education teachers at Sachsen. They had distributed questionnaires to over a

hundred leading artists and painters to find out their opinion of physical beauty and Turnen

(physical education). According to the artists, an even development of the body is beneficial

to beauty (see H. Thiele, Krperschnheit und Turnen, Monatsschrift fr das Turnwesen

[1913], 1).

Margarethe Streicher, Zur Erneuerung der Tanzkunst (Juli 1922), in Gaulhofer and

Streicher, Natrliches Turnen. Gesammelte Aufstze I, pp.2630, quotation p.29. See also:

Rudolf Hecker and Christian Silberhorn, Krpererziehung vom knstlerischen Standpunkt,

in idem. (eds.), Deutsche Krpererziehung. Ziele und Methoden der Krperbildung (Munich,

1923), pp.1005.

Streicher emphasized that the modern systems were ahead of gymnastics in this theory.

(Margarethe Streicher, Was kann das Turnen von den modernen Systemen lernen? (Februar

1924), in Gaulhofer and Streicher, Natrliches Turnen. Gesammelte Aufstze I, pp.107110.

Margarethe Streicher, Die Bedeutung der krperlichen bungen fr die Erziehung (Januar

1923), in ibid., pp.3440.

Lzl Moholy-Nagy, in Palucca. Portrt einer Knstlerin (Berlin [Ost]: Henschelverlag,

1972), p.60.

Knstler um Palucca. Ausstellung zu Ehren des 85. Geburtstages. Katalog. Staatliche

Kunstsammlung Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett (Dresden: Bauhaus, 1987), p.7.

Nohl, Die sthetische Wirklichkeit. Eine Einfhrung, p.24.

See Mary Wigman, Vom Wesen des knstlerischen Tanzes, in Rudolf von Laban and Mary

Wigman (eds.), Die tnzerische Situation unserer Zeit (Dresden, 1936), pp.810.

Oskar Schlemmer, Tagebuchaufzeichnung: Mechanisch abstrakt. (Tagebuch 7 September

1931), in Die Neue Sammlung Munich (ed.), Oskar Schlemmer und die abstrakte Bhne,

pp.313, quotation p.31.

In 1924 Palucca married Friedrich Bienert, son of the art patron Ida Bienert. To her circle

of acquaintances belonged Oskar Kokoschka, Paul Klee, Emil Nolde, Otto Dix, Walter

Gropius and Mary Wigman, who probably introduced Palucca into this circle. (Jarchow and

Stabel, Palucca. Aus ihrem Leben ber ihre Kunst, p.33). Ise Bienert, sister of Friedrich,

studied at the Bauhaus.

See Wassily Kandinsky, Kunst und Erziehung (1947), p.250f.

See Jarchow and Stabel, Palucca. Aus ihrem Leben ber ihre Kunst, p.92.

Bauhaus 2 (1928), 4, p.30.

Klein, FrauenKrperTanz. Eine Zivilisationsgeschichte des Tanzes, p.181.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Feasibility Study VS Business PlanDokument12 SeitenFeasibility Study VS Business PlanMariam Oluwatoyin Campbell100% (1)

- Sturtevant Inappropriate AppropriationDokument13 SeitenSturtevant Inappropriate AppropriationtobyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conflict of Gestures (Huberman)Dokument15 SeitenConflict of Gestures (Huberman)bahman taherianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gutai Art Manifesto SummaryDokument3 SeitenGutai Art Manifesto SummaryZuk HorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seamo X Paper ADokument18 SeitenSeamo X Paper Ad'Risdi ChannelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Affecting The Poor Performance in Mathematics of Junior High School Students in IkaDokument24 SeitenFactors Affecting The Poor Performance in Mathematics of Junior High School Students in IkaChris John GantalaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dezeuze - Hélio Oiticica's ParangolésDokument15 SeitenDezeuze - Hélio Oiticica's ParangolésMartha SchwendenerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 650 English Phrases For Everyday Speaking - Facebook Com LinguaLIB PDFDokument50 Seiten650 English Phrases For Everyday Speaking - Facebook Com LinguaLIB PDFMahmoud Abd El HadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abdullah AriffDokument13 SeitenAbdullah AriffAinaa Nadira100% (1)

- Race Time and Revision of Modernity - Homi BhabhaDokument6 SeitenRace Time and Revision of Modernity - Homi BhabhaMelissa CammilleriNoch keine Bewertungen

- E. Kosuth, Joseph and Siegelaub, Seth - Reply To Benjamin Buchloh On Conceptual ArtDokument7 SeitenE. Kosuth, Joseph and Siegelaub, Seth - Reply To Benjamin Buchloh On Conceptual ArtDavid LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sohl Lee, Images of Reality, Ideals of DemocracyDokument236 SeitenSohl Lee, Images of Reality, Ideals of DemocracyThiago FerreiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Auto Destructive Art Text RoutledgeDokument19 SeitenAuto Destructive Art Text RoutledgePa To N'CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Balkan Art Scene Vol 1 Issue 1Dokument59 SeitenBalkan Art Scene Vol 1 Issue 1Hana100% (1)

- Erasure in Art - Destructio..Dokument12 SeitenErasure in Art - Destructio..lecometNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational Leadership - Summer ClassDokument68 SeitenEducational Leadership - Summer ClassMENCAE MARAE SAPIDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hard Work Lee Lozanos Dropouts October 1 PDFDokument25 SeitenHard Work Lee Lozanos Dropouts October 1 PDFLarisa CrunţeanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, DematerialisationDokument36 SeitenAnna Dezeuze - Street Works, Borderline Art, DematerialisationIla FornaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art and Politics in Interwar Germany. The Photomontages of John HeartfieldDokument40 SeitenArt and Politics in Interwar Germany. The Photomontages of John HeartfieldFelipePGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roux - Participative ArtDokument4 SeitenRoux - Participative ArtTuropicuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leighten Picassos Collages and The Threat of WarDokument21 SeitenLeighten Picassos Collages and The Threat of WarmmouvementNoch keine Bewertungen

- RAYMOND - Claire. Roland - Barthes - Ana - Mendieta - and - The - Orph PDFDokument22 SeitenRAYMOND - Claire. Roland - Barthes - Ana - Mendieta - and - The - Orph PDF2radialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Potaznik ThesisDokument34 SeitenPotaznik ThesisItzel YamiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hoffmann Jens - Other Primary Structures IntroDokument4 SeitenHoffmann Jens - Other Primary Structures IntroVal RavagliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alexander Dorner - The Way Beyond Art1Dokument154 SeitenAlexander Dorner - The Way Beyond Art1Ross WolfeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pictorial Jeff WallDokument12 SeitenThe Pictorial Jeff WallinsulsusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Claire Bishop IntroductionDokument2 SeitenClaire Bishop IntroductionAlessandroValerioZamoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecole Ducasse - 2020 2021 PricingDokument4 SeitenEcole Ducasse - 2020 2021 PricingminkhangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digital Interactive Art To WhereDokument7 SeitenDigital Interactive Art To WhereMosor VladNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inside The Space ReadingsDokument16 SeitenInside The Space ReadingsNadia Centeno100% (2)

- Poverty and Inequality PDFDokument201 SeitenPoverty and Inequality PDFSílvio CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stanley Mayer Burstein - Agatharchides of Cnidus - On The Erythraean Sea-Routledge (1999)Dokument217 SeitenStanley Mayer Burstein - Agatharchides of Cnidus - On The Erythraean Sea-Routledge (1999)geoscientistoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classroom Language 2021Dokument37 SeitenClassroom Language 2021Shin Lae WinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dill Pickle ClubDokument9 SeitenDill Pickle ClubJustin BeckerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gregory Battcock - Minimal ArtDokument7 SeitenGregory Battcock - Minimal ArtLarissa CostaNoch keine Bewertungen

- For Some of Her Works, Barely Any Documentation Exists, But Here You Are Going To See Some Photographs of The Most Famous Preserved OnesDokument4 SeitenFor Some of Her Works, Barely Any Documentation Exists, But Here You Are Going To See Some Photographs of The Most Famous Preserved OnesKamilė KuzminaitėNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communicating Vessels ExtractDokument24 SeitenCommunicating Vessels ExtractSerge CassiniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lefebvre and SpaceDokument15 SeitenLefebvre and SpaceZainab CheemaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buchloh On Dada Texte Zur KunstDokument5 SeitenBuchloh On Dada Texte Zur Kunstspring_into_dadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Painting Became Popular AgainDokument3 SeitenHow Painting Became Popular AgainWendy Abel CampbellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Karl Ove Knausgård's Acceptence SpeechDokument15 SeitenKarl Ove Knausgård's Acceptence SpeechAlexander SandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ortega Exiled Space In-Between SpaceDokument18 SeitenOrtega Exiled Space In-Between Spacevoicu_manNoch keine Bewertungen

- Famous Malaysian ArtistsDokument16 SeitenFamous Malaysian ArtistsHannah LohNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Faktura To FactographyDokument39 SeitenFrom Faktura To FactographyLida Mary SunderlandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art Market Tensions in Philippine Contemporary ArtDokument53 SeitenArt Market Tensions in Philippine Contemporary ArtEileen Legaspi RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Primitivism and The OtherDokument13 SeitenPrimitivism and The Otherpaulx93xNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Circuit of Culture Ed ArunDokument3 SeitenThe Circuit of Culture Ed ArunArunopol SealNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conceptual Art: The Idea Over the ObjectDokument3 SeitenConceptual Art: The Idea Over the ObjectRichel BulacosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affective Politics of VoiceDokument19 SeitenAffective Politics of VoiceradamirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art in Italy in the 1980s: Beyond the Transavantgarde NarrativeDokument193 SeitenArt in Italy in the 1980s: Beyond the Transavantgarde Narrativeanushka pandiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outsider PhenomenonDokument5 SeitenOutsider Phenomenonmusic1234musicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ruscha (About) WORDSDokument5 SeitenRuscha (About) WORDSarrgggNoch keine Bewertungen

- Irit Rogoff Productive AnticipationDokument8 SeitenIrit Rogoff Productive AnticipationRozenbergNoch keine Bewertungen

- Francis Alys Exhibition PosterDokument2 SeitenFrancis Alys Exhibition PosterThe Renaissance SocietyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Turn and Its Discontents Claire BishopDokument7 SeitenSocial Turn and Its Discontents Claire BishopMiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art and PoliticsDokument15 SeitenArt and Politicsis taken readyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art and Politics in The 20th CenturyDokument7 SeitenArt and Politics in The 20th Centuryamars_aNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concrete Poetry and Conceptual ArtDokument21 SeitenConcrete Poetry and Conceptual Artjohndsmith22Noch keine Bewertungen

- RIEGL, Aloïs. 1995. Excerpts From The Dutch Group PortraitDokument34 SeitenRIEGL, Aloïs. 1995. Excerpts From The Dutch Group PortraitRennzo Rojas RupayNoch keine Bewertungen

- David Levi Strauss and Hakim BeyDokument8 SeitenDavid Levi Strauss and Hakim BeydekknNoch keine Bewertungen

- Le Feuvre Camila SposatiDokument8 SeitenLe Feuvre Camila SposatikatburnerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arsewoman in Wonderland: Ekphrastic Transformations of PornographyDokument30 SeitenArsewoman in Wonderland: Ekphrastic Transformations of PornographySolon14Noch keine Bewertungen

- Positioning Singapore S Contemporary Art PDFDokument23 SeitenPositioning Singapore S Contemporary Art PDFNur Saalim Wen LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interview - Johann Kresnik - TANZFONDSDokument5 SeitenInterview - Johann Kresnik - TANZFONDSodranoel2014Noch keine Bewertungen

- Photographer's Eye IntroductionDokument7 SeitenPhotographer's Eye IntroductionBecky BivensNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Dokument16 SeitenNotes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNoch keine Bewertungen

- L SZL Moholy Nagy and Chicago S War Industry Photographic Pedagogy at The New BauhausDokument21 SeitenL SZL Moholy Nagy and Chicago S War Industry Photographic Pedagogy at The New BauhausKata PaliczNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interview With Alvaro SizaDokument3 SeitenInterview With Alvaro SizaKata PaliczNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jungfrau RegionDokument3 SeitenJungfrau RegionKata PaliczNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Center Research Areas and TopicsDokument4 SeitenResearch Center Research Areas and TopicsedwineiouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Activity.2 21st Century EducationDokument7 SeitenActivity.2 21st Century EducationGARCIA EmilyNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Thematic Literature Review On Industry-Practice Gaps in TVETDokument24 SeitenA Thematic Literature Review On Industry-Practice Gaps in TVETBALQIS BINTI HUSSIN A18PP0022Noch keine Bewertungen

- ReflectionDokument8 SeitenReflectionapi-260964883Noch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Forest Service Exam Cut-Off Marks 2018Dokument1 SeiteIndian Forest Service Exam Cut-Off Marks 2018surajcool999Noch keine Bewertungen

- ED 227 Learner-Centered Teaching ApproachesDokument153 SeitenED 227 Learner-Centered Teaching ApproachesGeraldine Collado LentijaNoch keine Bewertungen

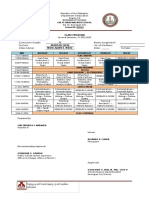

- Class Program (SY 2022-2023)Dokument12 SeitenClass Program (SY 2022-2023)Cris Fredrich AndalizaNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Members of The Browning Institute, Inc. Source: Browning Institute Studies, Vol. 12 (1984), Pp. 207-214 Published By: Cambridge University Press Accessed: 14-06-2020 09:58 UTCDokument9 SeitenList of Members of The Browning Institute, Inc. Source: Browning Institute Studies, Vol. 12 (1984), Pp. 207-214 Published By: Cambridge University Press Accessed: 14-06-2020 09:58 UTCsamon sumulongNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLL CNFDokument2 SeitenDLL CNFMARIA VICTORIA VELASCONoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan Gym VolleyballDokument9 SeitenLesson Plan Gym VolleyballAnonymous kDMD6iAp4FNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Govt. of India EnterpriseDokument11 SeitenA Govt. of India Enterprisebabakumaresh1982Noch keine Bewertungen

- Coursera MHJLW6K4S2TGDokument1 SeiteCoursera MHJLW6K4S2TGCanadian Affiliate Marketing UniversityNoch keine Bewertungen

- 59856-Module-3 Complex Number (Solution)Dokument24 Seiten59856-Module-3 Complex Number (Solution)shiwamp@gmail.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zuhaib Ashfaq Khan: Curriculum VitaeDokument6 SeitenZuhaib Ashfaq Khan: Curriculum VitaeRanaDanishRajpootNoch keine Bewertungen

- Earthquake Proof Structure ActivityDokument2 SeitenEarthquake Proof Structure ActivityAJ CarranzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sy 2019 - 2020 Teacher Individual Annual Implementation Plan (Tiaip)Dokument6 SeitenSy 2019 - 2020 Teacher Individual Annual Implementation Plan (Tiaip)Lee Onil Romat SelardaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV Julian Cardenas 170612 EnglishDokument21 SeitenCV Julian Cardenas 170612 Englishjulian.cardenasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Karl MannheimDokument7 SeitenKarl MannheimEmmanuel S. Caliwan100% (1)

- Banda Noel Assignment 1Dokument5 SeitenBanda Noel Assignment 1noel bandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theresa Farrell 20120529170641Dokument73 SeitenTheresa Farrell 20120529170641Anirban RoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher workplan goals for professional growthDokument6 SeitenTeacher workplan goals for professional growthMichelle Anne Legaspi BawarNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Learning Contracts Promote Individualized InstructionDokument6 SeitenHow Learning Contracts Promote Individualized Instructionchris layNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bullying Among Children and Adolescents in SchoolsDokument8 SeitenBullying Among Children and Adolescents in SchoolsrukhailaunNoch keine Bewertungen