Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Resistance

Hochgeladen von

Luiz Francisco Ferreira JuniorCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Resistance

Hochgeladen von

Luiz Francisco Ferreira JuniorCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Resisting the Pow er of the Empire: The Theme of Resistance in the Book of Daniel

Review and Expositor, 109, Fall 2012

Resisting the Power of Empire: The Theme of

Resistance in the Book of Daniel___________

By Barry A. Jones*

ABSTRACT

The recent theoretical perspective of postcolonial studies calls attention

to the practices that empires use to maximize and to legitimize their

uneven exercise of power, and to the efforts that subjected peoples use

to resist these practices. This article compares two representative

treatments of the book of Daniel from a postcolonial perspective. Daniel

provides a testimony to the efforts of Jews to be faithful to God under

the rule of foreign empires, culminating in acts of resistance to Antiochus

IV's persecution of the Jews in 167 to 164 bce . The article also considers

implications of the theme of resistance in Daniel for Christian faith and

ministry.

How can a faith community that yields ultimate allegiance to God live

faithfully under the rule of temporal powers that make competing claims to

ultimate sovereignty? While Daniel has often appealed to sectarian groups

that find themselves outside of mainstream traditions, its exotic symbolism

and "end times" perspective has held little appeal to Christians occupying

positions of cultural and political power. As the church increasingly finds

itself in the position of a minority religion in today's religiously pluralistic

context, the nature of the book of Daniel as resistance literature now has a

far greater relevance.

' Barry A. Jones is Associate Professor of Old Testament and Hebrew at the Divinity

School of Campbell University in Buies Creek, North Carolina.

541

The book reveals its concern for the plight of a

religious minority under the control of imperial

powers. In chapters 1-6, a collection of tales recounts

the efforts of Daniel and his companions to maintain

their distinct identity and religious fidelity while

living in forced servitude to successive gentile

empires. In chapters

7-12, the book shifts The book [of Daniel] reveals

to a more dire set of circumstances. Here, its concern for the plight of

Daniel the faithful scribe and inspired a religious minority under

interpreter of dreams receives a series of visions the contro1 of imPerial

<

<

!-

j

powers,

about a future empire far more fierce and

hostile than all its predecessors. The

interpretation of the visions given to Daniel by angelic interpreters points

specifically to the circumstances of persecution of the Jews by the Seleucid

king Antiochus IV Epiphanes in the years 168 to 164 b ce .

The themes of resistance to assimilation and persecution in Daniel have

always been clear to interpreters. Developments in biblical scholarship in

the last two decades, however, have brought greater attention to these themes

because of their resonance with issues arising in the last half of the twentieth

century. Since roughly the end of World War II, scholars in the West have

gained greater exposure to, awareness of, and critical perspective on the

nature of modem colonial expansion by Western nations and the concomitant

experiences and cultural responses of indigenous peoples living under

Western colonial rule. Postcolonial studies gives attention to the complex

dynamics between colonizing and colonized peoples and investigates the

structures and practices of empires.1 Although begun as an investigation of

the history and dynamics of Western European colonialism, postcolonial

studies also has application to the study of empires in antiquity, which

includes much of the history of the Bible itself.

The perspective of postcolonial biblical criticism brings the relationships

betw een the Jews and their im perial

The perspective of

overlords in the book of Daniel to the

postcolonial biblical criticism

foreground. Recent studies have brought the

brings the relationships

significance of the imperial context of the

between the Jews and their

writer(s) and audience of Daniel into sharper

imperial overlords in the book

focus. Postcolonial biblical criticism also

of Daniel to the foreground.

provides a new set of questions for

contemporary Christians who read Daniel as

sacred scripture and seek to translate its message into the life of faith. This

article will review the scholarship on Daniel that gives attention to life lived

1*8E

A B a pt ist T h e o l o g ic a l

Jo urnal

542

Resisting the Pow er o f the Empire: The Theme o f Resistance in the Book of Daniel

Review and Expositor, 109, Fall 2012

under empire and will examine some implications

of this perspective for Christian faith and ministry.

Daniel as Resistance Literature

T he B o o k

D a n ie l

of

F all 2012

The distinct character of Daniel as literature

arising from efforts to resist the totalizing power of

empire has been the focus of numerous studies in

recent scholarship. Two examples provide an overview of the dynamics of

resistance in the book of Daniel. These are Daniel Smith-Christopher's

commentary on Daniel in The New Interpreter's Bible,2 and Anathea PortierYoung's Apocalypse Against Empire: Jewish Theologies of Resistance.3 Both give

sustained attention to the context of domination by foreign empires and to

ways that this context is reflected in Daniel.4 At the same time, they provide

complementary perspectives on the theme of resistance.

Smith-Christopher: The Long Struggle of Exile and Diaspora

The tales of Daniel 1-6 take place against the narrative backdrop of the

Babylonian exile. The apocalyptic visions of

. . . the book of Daniel

Daniel 7-12, addressing the crisis of the Seleucid

portrays exile not only as an persecution centuries after the return from

event but also a paradigm

exile, are also placed within the narrative

of Jewish existence from the

framework of the Babylonian captivity. Thus,

fall of Judah to the

the book of Daniel portrays exile not only as

Hellenistic period and

an event b ut also a paradigm of Jewish

beyond.

existence from the fall of Judah to the

Hellenistic period and beyond.

Daniel's portrayal of the history of subordination from the exile through

the succeeding empires of Persia and Greece is well suited to the perspective

of postcolonial studies. Smith-Christopher has worked to bring the

perspective of the historical experience of exile to the attention of biblical

studies. As a result of his interrogation of the systems and methods of

empires, certain themes emerge within his commentary. First, he contradicts

claims of earlier scholarship that the Jewish experience of exile and imperial

rule was not particularly harsh and that the portrayals of foreign kings in

Daniel 1-6 cast them in a somewhat favorable light. There is an identifiable

tradition in biblical scholarship and within the biblical record itself that

diminishes the harsh realities of exile and imperial rule by emphasizing the

continuing identity of intact Jewish communities, the relative rise in status

of some Jews within the imperial bureaucracy, and the somewhat favorable

543

description of the Persian Empire that allowed the

resettlement and rebuilding of Jerusalem. This

tradition can have the effect of m uting textual

evidence of the injustice, violence, and mental and

physical distress of economic and political

dom ination by foreign pow ers over m ultiple

generations. When biblical portrayals of the exile

and the Persian and H ellenistic em pires are

examined through the lens of displaced and subjugated peoples, their

traumatic and oppressive nature comes more clearly into focus.

The dehumanizing aspects of imperial rule confront the reader in the

very first chapter of Daniel with the report of Nebuchadnezzar's siege and

conquest of Jerusalem (Dan 1:1).5 Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah

are taken as captives to Babylon for service

in the imperial court. Their Hebrew names

Daniel and his fellow Jews are

are replaced with Babylonian names as a

victims of war, abduction, and

symbol of their new identity and their new

forced servitude. Their names,

identities, and education are

overlord. Daniel and his fellow Jews are

replaced by new identities and

victims of war, abduction, and forced

they

are selected for a program

servitude. Their names, identities, and

of "reeducation" into the culture

education are replaced by new identities

of their captors.

and they are selected for a program of

"reeducation" into the culture of their

captors.6

Apologists for empires and colonial powers often defend the crimes and

injustices of ruling parties by pointing to the benefits these powers provided,

such as improved living standards and education into the superior knowledge

and culture of the conquering power. Often the "backwardness" and

"inferior" levels of technology and culture of the subjected population

provide a justification for its "enlightenment" by the empire. Daniel 1 rejects

any positive benefit from life in the royal court with regard to either health

or wisdom. First, Daniel and his companions refuse the food rations provided

from the king's table (Dan 1:8). When Daniel first proposes to abstain from

the royal food, the palace master replies that he is afraid of the repercussions

of changing the king's appointed rations. The palace master's fear of the

king and the presence of a guard to watch the four Jewish captives are

indications of the dark nature of their service in the royal court.7 Daniel,

however, proposes a trial period of ten days to compare the results of Daniel's

diet with that of the king's rations. The result of the test is that Daniel and his

friends "appeared better and fatter" than those who ate the king's food. A

further report of the narrator adds that "to these four young men God gave

knowledge and skill in every aspect of wisdom and literature" (Dan 1:17).

1^E

A B a pt ist T h e o l o g ic a l

Jo urnal

544

Resisting the P ow er of the Empire: The Theme of Resistance in the Book of Daniel

Review and Expositor, 109, Fall 2012

Neither their physical health nor their wisdom was

the result of the king's provisions. Rather, these were

T he B ook of

granted by God.

D aniel

Smith-Christopher finds further evidence of

hostility toward the empire in the reports of royal

F all 2012

dream s in Daniel 2 and 4. In D aniel 2,

N ebuchadnezzar has a disturbing dream and

commands the royal counselors to tell him both the

dream and its interpretation. The irrationality of his command and the

paranoia toward his advisers are additional elements of Daniel's critique of

im perial pow er.8 D aniel 4 contains a rep ort of another dream of

Nebuchadnezzar. Through divine assistance Daniel is able to interpret both

dreams. The shared theme of each dream is that the authority of the empire

derives from the authority of God, is temporary

[Nebuchadnezzar's] dreams

in nature, and will be overturned in God's time.

. . . provide a window into

Smith-Christopher notes that the dreams of

the inner hopes of Diaspora

Nebuchadnezzar are in reality the dreams that

Jews for the overthrow of

the Jewish author of Daniel placed in the mind

the powers that ruled over

of the king. The dreams therefore provide a

them.

window into the inner hopes of Diaspora Jews

for the overthrow of the powers that ruled over them.9

Nebuchadnezzar's dream of a statue made of four metals shares a

common image with Daniel 3, where Nebuchadnezzar commissions a gold

statue of himself to be worshiped by his subjects. Smith-Christopher notes

the penchant of colonizing powers for erecting statues honoring colonial

authorities and the deeds of colonization.10 Such displays reminded subject

peoples of their subordination to the occupying power, while also

engendering their resentment and scorn.

The story of Daniel's imprisonment in the lion's den in Daniel 6 reveals

another observation about life under imperial rule. Smith-Christopher notes

that references to imprisonment in the Old Testament, whether in narrative

texts or as a metaphor in psalms and poetry, are exclusively from the Second

Temple period. Imprisonment was not a common means of punishment or

state control in ancient Israel. Foreign rulers employed it in the Second Temple

period to such a degree that imprisonment could serve as a metaphor for the

experience of exile and imperial domination itself.11

Within the literary structure of the book of Daniel, chapters 7-12 mark a

radical transition from tales of Diaspora heroes to apocalyptic visions. While

Smith-Christopher acknowledges the literary features of the visions and notes

their darker tone, he nevertheless sees an essential continuity between the

negative portrayal of kings and empires in chapters 1-6 and chapters 7-12.

545

The portrayal of the four empires in Daniel 7 as

monstrous beasts arising from the primordial

chaos is, for him, a harsher description of the

irrational, dangerous, proud, and power-mad

monarchs of chapters 1-6.12The reinterpretation of

Jeremiah's seventy-year prophecy in Daniel 9

characterizes the persecutions of Antiochus IV

Epiphanes as an extreme example of imperial

domination, but one nevertheless consistent with the experiences that began

with the Babylonian conquest and continued under Persian and Hellenistic

rule.13

A prolonged history of foreign domination requires that an oppressed

population develop positive, proactive

practices of identity formation, boundary

A prolonged history of foreign

maintenance, and political resistance in

domination requires that an

oppressed population develop

order to survive the threat of cultural

positive, proactive practices of

assimilation. Smith-Christopher highlights

identity formation, boundary

a number of such communal practices in the

maintenance, and political

book of Daniel that sustained Jewish identity

resistance in order to survive

un d er the conditions of im perial

the threat of cultural

assimilation.

domination. To that end, the book serves as

a kind of training manual for political and

religious resistance.14

First, the preservation and transmission of hero stories is itself an

important strategy for resistance.15 The narratives of Daniel preserve several

positive strategies for political resistance. The first strategy is found in chapter

one, in Daniel's determination "that he would not defile himself with the

royal rations of food and wine" (Dan 1:8). The language of defilement is

overtly religious and its general motivation comes from the Levitical dietary

laws. Smith-Christopher notes the cultural role dietary laws play in forming

and maintaining community identity. Daniel's determination to avoid

defilement from the king's food in chapter 1 is also relevant to the Seleucid

persecution at the heart of chapters 7-12, since forced violation of Jewish

dietary laws was one means of persecution.

Smith-Christopher also highlights the role of prayer and fasting in Daniel

as acts of resistance to oppressive power. Prayer and fasting are features of

both the court tales and the visions and act as a bridge between the two

literary sections of the book. In Daniel 2, Daniel summons his community to

prayer when he is confronted with Nebuchadnezzar's threat of execution of

the sages if they do not reveal to him the content and interpretation of his

dream (Dan 2:17-18). Prayer and fasting are also prominent themes in Daniel

A B a ptist T h e o l o g ic a l

Journal

546

Resisting the Pow er of the Empire: The Theme o f Resistance in the Book of Daniel

Review and Expositor, 109, Fall 2012

9 and 10. At the heart of Daniel 9 is a prayer of

penitence that reflects a long tradition of communal

T he B o o k o f

prayers that developed in the Second Temple period

D aniel

(Dan 9:4-19). In Daniel 10, Daniel receives another

revelation following a twenty-one day fast. SmithF all 2012

C hristopher describes prayer and fasting as

communal forms of non-violent "spiritual warfare"

that are available to oppressed communities when

other forms of resistance are not viable either as a result of the oppressive

power's superior force or because other forms of physical resistance would

violate the community's non-violent ethic.16

The narratives of Daniel 3 and Daniel 6 feature acts of political resistance

through refusal to obey laws that violate core religious convictions. In Daniel

3, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah refuse to

The narratives of Daniel 3

bow down to Nebuchadnezzar's statue of gold

and Daniel 6 feature acts of

under threat of execution. Though they are

political resistance through

miraculously rescued from the fiery furnace,

refusal to obey laws that

their declaration to Nebuchadnezzar makes

violate core religious

clear that they are prepared to die rather than

convictions.

submit to coerced idolatry (Dan 3:17-18). This

act of defiance also resonates with experiences of persecution during the

Seleucid crisis. In Daniel 6, Daniel is threatened with death from the state

for refusing to obey an imperial command. In this case, the command is in

the form of a spurious law limiting prayer to none but the emperor alone.

Daniel not only refuses to comply, but continues his previous pattern of prayer

under public display. Smith-Christopher characterizes this action as an act

of "civil disobedience," an intentional refusal to obey an unjust law in order

to bring public attention to an unjust law.17

In Daniel's final vision in chapters 10-12, he receives a revelation about

the events of the Seleucid persecution that includes the actions of a group

called "the wise among the people" who "give understanding to many" (Dan

11:33). This group is generally understood to be the group responsible for

the visions of Daniel 7-12 as well as the collection of tales in Daniel 1-6. "The

wise" (hammakilim) pursue an active strategy of resistance to imperial

domination primarily by teaching the people the otherwise hidden truth

about their circumstances: that God is the true sovereign and events on earth

have been determined by decisions made in heaven.18The book of Daniel is

both the result and the content of this teaching ministry.

Smith-Christopher's research into the long-term effects of imperial

domination in the first four centuries of early Judaism leads him to emphasize

the general structural features of empire underlying the book of Daniel. The

547

persecutions of Antiochus IV in 167 bce called

forth all of the strategies and practices of communal

identity formation

and resistance that The persecutions of Antiochus

the community of IV in 167 bce called forth all of

strategies and practices of

the book of Daniel the

communal identity formation

could muster. Ac- and resistance that the

cording to Smith- community of the book of Daniel

Christopher, however, these strategies were could muster.

developed over the long period of resistance

to as-similation and foreign domination under the Babylonian, Persian, and

Hellenistic empires.

A B a ptist T h e o l o g ic a l

Jo urnal

Anathea Portier-Young, The Historical Apocalypses as Resistance Literature

If Smith-Christopher emphasized the long history of resistance to empire

reflected in Daniel, Anathea Portier-Young's Apocalypse Against Empire focuses

on the specific years of 167-164 bce . Portier-Young highlights the relationship

between two unprecedented events in early Jewish history. The first was

Antiochus IV's edict of 167 bce that outlawed the practice of traditional Jewish

religion in Judea, an exercise of imperial power previously unknown among

Hellenistic rulers. And the second was the appearance of the earliest Jewish

examples of historical apocalypse, including the book of Daniel. Portier-Young

argues that Seleucid imperial rule of Judea provided the sociological and

ideological setting for this genre of literature, which emerged as part of a

movement of resistance to the dominating forces of Hellenistic empire.19 Her

work explores the nature of Daniel as resistance literature by considering

three major components: 1) the theory of resistance as a political movement;

2) the historical record of Seleucid imperial rule over Judea; and 3) the literary

evidence for resistance in the text of Daniel.

Contemporary political theories of resistance reveal that dominant powers

exercise their rule by means of superior force (domination), which includes

acts of coercion and structures of political control, and through non-coercive

strategies and discourse that seek to make the structures of domination appear

to be the only possible arrangement of relationships (hegemony).20 Resistance

seeks to limit the exercise of both expressions of imperial power. The writers

of Daniel did not attempt to remain unseen or to limit their resistance to a

hidden world of discourse only, but rather attempted to unify the realms of

thought and action, mind and body, and belief and practice that imperial

hegemony sought to divide, as well as to expose the means by which the

Seleucid regime pursued its totalitarian goals.21 The device of pseudonymity

548

Resisting the Pow er o f the Empire: The Theme o f Resistance in the Book o f Daniel

Review and Expositor, 109, Fall 2012

served to give their message the authority of

received tradition rather than to protect the identity

T he Book of

of the authors. They exercised their speech and

D a n ie l

actions of resistance in the public arena and

encouraged and taught others to do so as well.

F a ll 2012

Portier-Young gives a historical analysis of the

period of Hellenistic rule over Judea that sets the

unprecedented actions of Antiochus IV's persecution

within the framework and logic of imperial domination. Although often

described by ancient and modem histories as a time of peaceful coexistence,

she argues that the Seleucid Empire's reign over Judea from 200 to 167 b ce

created numerous stresses for the Judean population. Hellenistic kings from

Alexander forward were first and foremost

Imperial rule over Judea,

military conquerors who gained their status

whether by the Ptolemies or

and wealth by the sword. Imperial rule over

Seleucids, was a combination

Judea, whether by the Ptolemies or Seleucids,

of military occupation or

was a combination of military occupation or

threatened occupation, social

threatened occupation, social and political

and political control, and

control, and economic extraction to enrich the

economic extraction to enrich

the empires and to feed their

empires and to feed their armies. The empires

armies.

created and exploited internal divisions and

unequal distributions of power among the

local leadership within Judea. Local control of religious institutions and

traditions became objects of negotiation in the power relationships between

empire and subject peoples.22

Rather than attributing the cause of Antiochus IV's persecution to the

internal dynamics in Judea, Portier-Young focuses attention on the wider

relations between the Seleucid, Ptolemaic, and Roman Empires. As the

growing power of Rome limited the reach and diminished the finances of

the Seleucid Empire, the Seleucid kings began to expand their control over

local temples as additional sources of revenue, including the temple in

Jerusalem. Internal struggles in Judea from 175-167 bce resulting from the

imperial "sale" of temple control led to infighting and ultimately revolt.

Portier-Young argues that this revolt provided Antiochus IV with a pretext

for a "reconquest" of Judea.23 Since Hellenistic kingship was defined by

military conquest, the reconquest of a region was a means of reasserting

control and "recreating" the empire. In light of this, Antiochus IV's

unprecedented persecution can nevertheless be understood within the logic

of an empire's control of a conquered region.

Portier-Young describes the particular mechanism of Antiochus IV's

reconquest of Judea as the intentional use of "state terror."24 State terror is

defined as an attempt to destroy the physical and psychological world of a

549

subject population in order to replace the destroyed

world with one imposed by the state, thereby

rendering the subject population incapable of

resistance. Since the religious traditions of Judaism

were part of the ordered world that gave the Judean

population a sense of identity and security,

Antiochus' edict outlawing the practice of Jewish

religion, while unprecedented, was nevertheless

consistent with the strategy of state terror.25 By carefully sifting the historical

record in light of the ways empires seek to sustain and "normalize" their

uneven exercise of power, Portier-Young has provided a detailed portrait of

the conditions that generated the responses to conquest and state terror in

the visions and tales of Daniel. What means of resistance did the authors of

that text promote?

Portier-Young describes an active program of resistance to the persecution

of Antiochus IV modeled on the faith and practice of Daniel and openly

pursued and advocated by the community

The writers of Daniel were

that created the book. She joins Smithactively and publicly engaged

Christopher in rejecting Paul Hanson's earlier

through their apocalyptic

view of apocalyptic visionaries as sectarian

teachings in a struggle for the

groups that sought to escape social

very life of their community.

responsibility by retreating into otherworldly visions.26The writers of Daniel were

actively and publicly engaged through their

apocalyptic teachings in a struggle for the very life of their community.

The composition of the book of Daniel is itself a major part of the makilim's

resistance. Portier-Young sees a clue to this claim in the two languages used

in the book's composition, Hebrew and Aramaic.27The book begins in Hebrew

as a representation of its continuity with Israelite covenant traditions and

the particularity of Judean identity. In Dan 2:4, the language changes to

Aramaic, the language of the Persian Empire, as a reflection of the Jews'

history of subjugation to foreign empires. The report of the judgment

announced there against the "little horn" of the fourth kingdom (Antiochus

IV Epiphanes) in the first vision in Daniel 7 signals a shift in disposition

toward earthly kingdoms. Following Daniel 7, the writing switches back to

Hebrew, to indicate that the time of limited cooperation with empires has

ended and that open resistance was now the only faithful response available.

The intentional blending of the two languages signals that the older tales of

Daniel 1-6 were incorporated into the Hebrew and Aramaic book at this time.

The tales of Daniel and his friends in exile became narrative models of

faithfulness for the Judeans under persecution.28In story and vision, the book

1Se

A B a pt ist T h e o l o g ic a l

Jo u r n a l

550

Resisting the Pow er of the Empire: The Theme o f Resistance in the Book of Daniel

Review and Expositor, 109, Fall 2012

of Daniel advocates resistance to the persecution of

Antiochus IV through knowledge of God that leads

T he B ook of

to covenant fidelity, practices and postures of prayer

D a n ie l

and penitence, instruction of the people in faithful

resistance, martyrdom, active waiting, and the study

F all 2012

and interpretation of scripture.

Portier-Young highlights the recurring theme of

knowledge as a source of strength in the visions of

Daniel.29 Daniel 11:32 affirms that "those who know their God will stand

strong and act." Knowledge of God is a technical term for the covenant

relationship. By focusing on the Jewish people's covenant obligation and

God's mutual obligations to the covenant people, the book of Daniel denies

Antiochus IV's claims to sovereignty and transposes questions of obedience

to a higher plane.

Another expression of resistance is through acts of worship and prayer.30

Daniel receives strength, assistance, and revelation from angelic interpreters

in response to his attitude, posture, and

practice of prayer, particularly his penitential

Penitence is a way of

prayer

in Daniel 9. The posture and attitude

accepting shame from God,

of

prayer

and fasting yield the body to God,

thus denying the king the

denying

the

authority of the king over the body

ability to control the people

through the shaming

and affirming the greater sovereignty of God

associated with torture and

even in the circumstance of persecution.

other forms of state terror.

Penitence is a way of accepting shame from

God, thus denying the king the ability to

control the people through the shaming associated with torture and other

forms of state terror.

Daniel 11:33 and 12:3 describe a situation in which the wise instruct the

many in the ways of faithful resistance and suffer persecution and death as a

result. The language of 12:3, echoing Dan 9:24, suggests a purifying and even

atoning function to the wise teachers' martyrdom.31 As the temple sacrifices

have been interrupted, the purposes of the sacrifices are replaced by the selfsacrifice of the wise in a manner similar to the vicarious suffering of the

servant in Isaiah 53. The possibility that the Suffering Servant poem served

as a model for the self-understanding of the makilim suggests that the study

and searching of the scriptures were further means of resisting the program

of Antiochus IV and denying the alternative world order than he sought to

impose.32 Finally, the book ends with the angel Gabriel's benediction on those

who wait until the end (Dan 12:12). This benediction serves as a commission

to the audience of the book to wait for God to act by actively engaging in

non-violent resistance to the com m ands of A ntiochus IV and by

551

demonstrating faithfulness to covenant piety as

modeled by the literary hero Daniel.33

Smith-Christopher and Portier-Young both

depict the writer(s) of the book of Daniel as actively

engaged in a program of resistance to the political

powers of the time in creative, intentional, and

religiously inspired ways. An examination of the

book of Daniel through the lens of postcolonial

studies reveals the life and death significance of the theological and ethical

issues confronting the book's writers and audience. As a result, contemporary

Christians have greater clarity with which to reflect on the theological and

.ethical significance of Daniel for the present day

1^E

A B a ptist T h e o l o g ic a l

Jo urnal

Implications of the Theme of Resistance for Contemporary Ministry

The book of Daniel presents the world as a highly contested space in

which dominant powers constantly threaten weaker groups with coerced

assimilation or violent extermination. In exalting themselves to a status of

ultimacy that belongs only to God, such powers reveal themselves as

representations of an idolatry that tends toward the demonic. Those who

take the perspective of Daniel are led to ask what place they might occupy in

.such a world

During the long tenure of Christendom, the social location of the church

was most analogous to the status of Daniel and his friends in the royal court

of Judah prior to their capture by Nebuchadnezzar. The church has been

closely aligned with and in service to the power of Western kingdoms and

,nations for the majority of its history. The rise of secularism in the West

however, has significantly diminished

the accustomed p

ow er and p

riv ile g e o

Although no one event has brought

power

privilege

off

about !or has even signaled the

the church. Although no one event has

1 J.U

church s new status as a minority

brought about or has even signaled the

jnt0rest jn a p|ura|jstic age jts

church's

-church's new

new status

status as

as aa m

minority

inority

current situation has been fre

interest in a pluralistic age, its current

quently compared to the status of

situation has been frequently

an exile somewhat analogous to

compared to the status of an exile

the plight of Daniel and his friends

.somewhat

somewhat analogous

analogous to

to the

the plight

plight of

of

in Nebuchadnezzar's court

Daniel and his friends in

Nebuchadnezzar's court.34

In employing the book of Daniel as a model for being a faithful minority

in a threatening world, the church does well to consider the two distinct

settings and challenges portrayed in the book. Chapters 1-6 address the

challenge of maintaining faithful allegiance in the face of the temptation to

552

Resisting the Power of the Empire: The Theme of Resistance in the Book of Daniel

Review and Expositor, 109, Fall 2012

assimilate to the values of the prevailing social order.

Chapters 7-12 address the threat of annihilation by

T he B ook of

coercive powers that use violence and terror as

D aniel

mechanisms of control. The combination of the tales

of Diaspora with the visions of deliverance suggests

F all 2012

that faithful resistance is a product of a long history

of community formation. The exilic literary setting

of the book presents an im age of a religious

community that has been shaped by a long tradition

of worship, prayer, study, teaching, and sustained obedience to its covenantal

traditions. The crisis of persecution revealed in the visions portrays a

community responding in the moment out of the habits, practices, and

theological vision that shaped it during a long history of Diaspora existence.

Therefore, one way in which the church might appropriate the nature of

the book of Daniel as resistance literature is to attend to the habits and

practices of communal identity that it describes, including: attending to the

body through traditioned patterns of eating, drinking, fasting, and postures

of humility before God; practices of prayer, liturgical worship and scripture

study; and practices of public witness such as teaching, resisting coerced

acts of idolatry, non-violently seeking the welfare of one's enemies, and even

yielding one's body to punishment, imprisonment, torture, and death as

public testimony of trust in God as the ultimate author and judge of the

living. Smith-Christopher concludes that the most important thing the Jews

responsible for the book of Daniel did was to be Jews.35 That is to say, the

most important thing was to be a distinct community set apart from the world

around them, with an identity based upon faith in the God of Israel and

disciplined faithfulness to the covenant.

The history of established Christianity in the West should not lull

Christians into complacency about the

The history of established

reality of religious persecution. Nor can the

Christianity in the West should

church ignore its own complicity in colonial

not lull Christians into

forms of persecution in the past. Postcolonial

complacency about the reality

perspectives

on the structures and behaviors

of religious persecution. Nor

of

totalitarian

empires as portrayed in Daniel

can the church ignore its own

should heighten the church's awareness of

complicity in colonial forms of

persecution in the past.

global Christian minorities who do not have

the accum ulated protections from

persecution afforded by the legacy of Western Christianity.

The book of Daniel's program of resistance includes two distinct

convictions: that resistance should be non-violent, and that the hope of

resurrection should sustain those who remain faithful to the point of death.

The church's renewed attention to the status it shares with the community of

553

Daniel as a religious minority in an age of pluralism

may help it reconnect with the central values of its

earliest history that have been diminished by its

privileged social status. The book of Daniel also

reconnects the church to its roots in Judaism from

which it originally received the gifts of non-violence

and the hope for resurrection. Judaism is a reminder

to Christianity that a religious community can have

both a distinct identity and a public witness as a

minority faith in a pluralistic age.

A B a pt ist T h e o l o g ic a l

Jo u r n a l

1 Helpful introductions can be found in Stephen D. Moore, Empire and Apocalypse:

Postcolonialism and the New Testament (Sheffield: Phoenix Press, 2006), 3-23; and R. S.

Sugirtharajah, Charting the Aftermath: A R eview of Postcolonial Criticism," in The

Postcolonial Biblical Reader, ed. R.S. Sugirathajah (Oxford: Blackwell, 2006), 7-31.

2 Daniel Smith-Christopher, The Book of Daniel," in The New Interpreter's Bible, vol.

VII, ed. Leander E. Keck (Nashville: A bingdon Press, 1996), 17-152.

3 Anathea Portier-Young, Apocalypse Against Empire: Theologies of Resistance in Early

Judaism (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2011). Jim Hee Han also

addresses the theme of resistance in Daniel in his book, Daniel's Spiel: Apocalyptic Literacy

in the Book of Daniel (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2008). His focus on resistance

to Hellenistic culture, however, is covered more thoroughly and with much greater detail

by Portier-Young.

4Treatment of the book as a w hole separates these two works from other recent works

using a similar approach yet focusing primarily on chapters 1-6. A m ong these are Danna

Nolan Fewell, Circles of Sovereignty : Plotting Politics in the Book of Daniel (Nashville: Abingdon

Press, 1991); Shane Kirkpatrick, Competing for Honor in Daniel 1-6 (Leiden: Brill, 2005); and

David Valeta, Lions and Ovens and Visions: A Satirical Reading of Daniel 1-6 (Sheffield: Sheffield

Phoenix, 2008).

5 All Scripture citations are from the NRSV unless otherwise noted.

6 Smith-Christopher, Daniel," 38-39. For a detailed treatment of Daniel 1 from a

postcolonial perspective, see Philip Chia, On N am ing the Subject: Postcolonial Reading

of Daniel 1," in The Postcolonial Biblical Reader (Oxford: Blackwell, 2006), 171-84. For the

criticism that Daniel 1 actually dow nplays the horrors experienced by Daniel and friends,

including the possibility of forced castration as eunuchs in the royal court, see Dana N.

Resisting the Power o f the Empire: The Theme of Resistance in the Book of Daniel

Review and Expositor, 109, Fall 2012

Fewell, The Children of Israel: Reading the Bible for the Sake of Our

Children (Nashville: Abingdon, 2003), 117-30.

7 Ibid., 40.

8 Ibid., 51-52.

T he B oo k

D a n ie l

of

F a ll 2012

9Ibid., 58-59.

10 Ibid., 65-66.

11Ibid., 89-91.

12 Am ong the commentators w ho em phasize a change in portrayal of the nature of the

k ingd om s from nations that offer both danger and op portu nity to m ythical beasts

representing the forces of chaos, see John J. Collins, Daniel: A Commentary on the Book of

Daniel (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), 323; and Portier-Young, Apocalypse against Empire,

227.

13 Smith-Christopher, "Daniel," 122.

14 An important contribution to seeing Daniel in this light is W. Lee Humphreys, "A

Life-Style for Diaspora: A Study of the Tales of Esther and Daniel," Journal of Biblical Literature

92 (1973): 211-23.

15 Smith-Christopher, Religion of the Landless (Bloomington, IN: Meyer-Stone Books,

1989), 153-78.

16 Smith-Christopher, "Daniel," 52, 124-25.

17 Ibid., 91-92.

18Ibid., 151.

19 Portier-Young, xxi-xxii.

20 Ibid., 44.

21 Ibid., 36-37.

22 Ibid., 62-73.

23 Ibid., 136-38.

24 Ibid., 141-42.

25 Ibid., 176-78.

555

1^E

26 Ibid., 217; Smith-Christopher, "Daniel," 20; Paul

H an son , The Dawn of Apocalyptic: The Historical and

Sociological Roots of Jewish A pocalyptic Eschatology

(Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1979), 26.

27 Portier-Young, 227-28.

A B a pt ist T h e o l o g ic a l

Journal

28 Ibid., 234.

29 Ibid., 235-36.

30 Ibid., 243-44.

31 Ibid., 256-57.

32 Ibid., 265-74.

33 Ibid., 263-65.

34 The analogy between the Babylonian exile and the status of the post-Christendom

church is the prem ise of Smith-Christopher,s A Biblical Theology of Exile (Minneapolis:

Fortress Press, 2002). See also Walter Brueggemann, Cadences of Home: Preaching among

Exiles (Louisville: W estm inster-John Knox, 1997); and m ore recently Out of Babylon

(Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2010).

35 Smith-Christopher, "Daniel," 150.

556

Copyright and Use:

As an ATLAS user, you may print, download, or send articles for individual use

according to fair use as defined by U.S. and international copyright law and as

otherwise authorized under your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement.

No content may be copied or emailed to multiple sites or publicly posted without the

copyright holder(sV express written permission. Any use, decompiling,

reproduction, or distribution of this journal in excess of fair use provisions may be a

violation of copyright law.

This journal is made available to you through the ATLAS collection with permission

from the copyright holder( s). The copyright holder for an entire issue of ajournai

typically is the journal owner, who also may own the copyright in each article. However,

for certain articles, the author of the article may maintain the copyright in the article.

Please contact the copyright holder(s) to request permission to use an article or specific

work for any use not covered by the fair use provisions of the copyright laws or covered

by your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement. For information regarding the

copyright holder(s), please refer to the copyright information in the journal, if available,

or contact ATLA to request contact information for the copyright holder(s).

About ATLAS:

The ATLA Serials (ATLAS) collection contains electronic versions of previously

published religion and theology journals reproduced with permission. The ATLAS

collection is owned and managed by the American Theological Library Association

(ATLA) and received initial funding from Lilly Endowment Inc.

The design and final form of this electronic document is the property of the American

Theological Library Association.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Music Ministry Handbook - Music Ministry WorkshopDokument28 SeitenMusic Ministry Handbook - Music Ministry Workshopgeorgeskie8Noch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding-Righteousness - T.L. Osborn - 21 - 27Dokument7 SeitenUnderstanding-Righteousness - T.L. Osborn - 21 - 27pcarlosNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Salutation To MaryDokument4 SeitenA Salutation To MarySanu PhilipNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book ReviewDokument4 SeitenBook Reviewsyed ahmadullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- UC Pikareum Workshops in Japan 1991Dokument6 SeitenUC Pikareum Workshops in Japan 1991HWDYKYMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resistance Theme in Daniel 1Dokument28 SeitenResistance Theme in Daniel 1Moises AcayanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Women in Mark's GospelDokument12 SeitenWomen in Mark's GospelgregnasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paul and PovertyDokument21 SeitenPaul and PovertyJaison Kaduvakuzhiyil VargheseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Koet Umbruch Korr04Versand20181206BJK PDFDokument327 SeitenKoet Umbruch Korr04Versand20181206BJK PDFMarko MarinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To LeviticusDokument19 SeitenIntroduction To LeviticusLawrence GarnerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1&2 SamuelDokument31 Seiten1&2 SamuelLusila Retno Utami0% (1)

- Ot Theology Waltke PDFDokument7 SeitenOt Theology Waltke PDFJuan Meneses FlorianNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1sam 12 12 Interpretation 1967 Lys 401 20Dokument20 Seiten1sam 12 12 Interpretation 1967 Lys 401 20Jac BrouwerNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDFDokument6 SeitenPDFMirabelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ratzinger11 3Dokument17 SeitenRatzinger11 3David T. Ernst, Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jephthah Sacrifice - How To Keep A Vow and Break A CovenantDokument10 SeitenJephthah Sacrifice - How To Keep A Vow and Break A CovenantmarcusmokNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Genesis Pt. 1 Study GuideDokument8 Seiten1 Genesis Pt. 1 Study GuideErant LuciNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book of EzraDokument5 SeitenBook of EzraEba Desalegn100% (1)

- ImageDokument111 SeitenImageJair Villegas BetancourtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complete Dissertation PDFDokument456 SeitenComplete Dissertation PDFZara HnamteNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Coniectanea Biblica. New Testament Series 20) Lilian Portefaix-Sisters Rejoice. Paul's Letter To The Philippians and Luke-Acts As Seen by First-Century Philippian Women - Almqvist & Wiksell InternatiDokument284 Seiten(Coniectanea Biblica. New Testament Series 20) Lilian Portefaix-Sisters Rejoice. Paul's Letter To The Philippians and Luke-Acts As Seen by First-Century Philippian Women - Almqvist & Wiksell InternatiCristina LupuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samson A Tragedy in Three ActsDokument7 SeitenSamson A Tragedy in Three ActsAlex LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book Critique of "Ancient Near Eastern Themes in Biblical Theology" by Jeffrey J. NiehausDokument8 SeitenBook Critique of "Ancient Near Eastern Themes in Biblical Theology" by Jeffrey J. NiehausspeliopoulosNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Memory of Her-A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins-Elisabeth Schussler FiorenzaDokument20 SeitenIn Memory of Her-A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins-Elisabeth Schussler FiorenzaAngela Natel100% (1)

- Joel 3:1-5 (MT and LXX) in Acts 2:17-21Dokument13 SeitenJoel 3:1-5 (MT and LXX) in Acts 2:17-21Trevor Peterson0% (1)

- 03 - Leviticus PDFDokument162 Seiten03 - Leviticus PDFGuZsolNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15 - Ezra PDFDokument55 Seiten15 - Ezra PDFGuZsolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dalit BibliographyDokument5 SeitenDalit BibliographyKaushik RayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Weber, Hans-Ruedi, The Gospel in The ChildDokument8 SeitenWeber, Hans-Ruedi, The Gospel in The ChildCarlos AresNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Story of Zerubbabel-Libre PDFDokument3 SeitenThe Story of Zerubbabel-Libre PDFShawki ShehadehNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Women in Mark's GospelDokument7 SeitenThe Role of Women in Mark's GospelRichard BaliliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community: Biblical and Theological Reflections in Honor of August H. KonkelVon EverandCommunity: Biblical and Theological Reflections in Honor of August H. KonkelRick Wadholm Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Commentary 2kDokument145 SeitenCommentary 2kNeil Retiza AbayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hope in Suffering & Joy in Liberation Course Poetry & Wisdom LiteratureDokument11 SeitenHope in Suffering & Joy in Liberation Course Poetry & Wisdom LiteratureECA100% (1)

- MK 11 - A Triple IntercalationDokument13 SeitenMK 11 - A Triple Intercalation31songofjoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commentary On The Gospel of John, Chapters 13-21 (PDFDrive)Dokument333 SeitenCommentary On The Gospel of John, Chapters 13-21 (PDFDrive)Delcide TeixeiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Esther (M.V. Fox)Dokument123 SeitenEsther (M.V. Fox)igorbosnicNoch keine Bewertungen

- 07 Lazarus TroublesDokument18 Seiten07 Lazarus TroublesNishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abraham S Sacrifice Gerhard Von Rad S inDokument10 SeitenAbraham S Sacrifice Gerhard Von Rad S inAngela NatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bullinger, Heinrich - A Hundred Sermons On The Apocalypse of Jesus Christ (1561)Dokument713 SeitenBullinger, Heinrich - A Hundred Sermons On The Apocalypse of Jesus Christ (1561)Gee100% (1)

- Book Report On Re-Reading The Bible With New Eyes.: Biblical Hermeneutics: Methods and PerspectivesDokument5 SeitenBook Report On Re-Reading The Bible With New Eyes.: Biblical Hermeneutics: Methods and PerspectivesNIMSHI MCC100% (1)

- 11 - Miracles of JesusDokument3 Seiten11 - Miracles of JesusMicah EdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hobson. Notes On The Athanasian Creed. 1894.Dokument96 SeitenHobson. Notes On The Athanasian Creed. 1894.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Bauckham, Richard, Jesus and The Eyewitnesses - The Gospels As Eyewitness TestimonyDokument2 SeitenReview Bauckham, Richard, Jesus and The Eyewitnesses - The Gospels As Eyewitness Testimonygersand6852Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jonah Workshop PathwaysDokument25 SeitenJonah Workshop PathwaysJohn D NettNoch keine Bewertungen

- Walther EichrodtDokument3 SeitenWalther Eichrodtscott_callaham100% (1)

- Biblical Understanding of NarrativesDokument12 SeitenBiblical Understanding of Narrativesjoshua immanuelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Niditch, Samson As Culture HeroDokument18 SeitenNiditch, Samson As Culture HeroRasmus TvergaardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ruth Langer - Minhag Parent's Blessing ChildrenDokument21 SeitenRuth Langer - Minhag Parent's Blessing Childrene-jajamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sermon On Psalm 137Dokument12 SeitenSermon On Psalm 137Jeff Jones100% (1)

- Commentary To The Book of Hosea - Rev. John SchultzDokument78 SeitenCommentary To The Book of Hosea - Rev. John Schultz300r100% (1)

- The Circumstances and Theology of Jeremiah: Prophetic Response, Sheffield: Sheffield Pheonix, 2006, 54Dokument4 SeitenThe Circumstances and Theology of Jeremiah: Prophetic Response, Sheffield: Sheffield Pheonix, 2006, 54Crispin Nduu Muyey100% (1)

- The Meaning and Function Of: Testament, Vol 1 (Chicago: Moody Press, 1980), 241Dokument19 SeitenThe Meaning and Function Of: Testament, Vol 1 (Chicago: Moody Press, 1980), 241Sheni OgunmolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paul in EcstasyDokument10 SeitenPaul in EcstasymalcroweNoch keine Bewertungen

- W Paroschi - Another Paraclete - ATS 2016Dokument24 SeitenW Paroschi - Another Paraclete - ATS 2016javierNoch keine Bewertungen

- Studying The Bible - The Tanakh and Early Christian WritingsDokument191 SeitenStudying The Bible - The Tanakh and Early Christian WritingsEmilyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1982 Gundry On MattDokument11 Seiten1982 Gundry On Mattxal22950100% (2)

- ElihuDokument34 SeitenElihuAbraham RendonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Koester, C. R. - Barr, David R. Et Alli, Revelation As A Critique of EmpireDokument111 SeitenKoester, C. R. - Barr, David R. Et Alli, Revelation As A Critique of EmpireCarlos MachadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Literary and Theological Analysis of The Book of EzraDokument226 SeitenA Literary and Theological Analysis of The Book of EzraDonald LeonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forsaken, Forgotten and Forgiven - A Devotional Study of Jeremiah and LamentationsVon EverandForsaken, Forgotten and Forgiven - A Devotional Study of Jeremiah and LamentationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 19 Isaiah 930-1014Dokument85 Seiten19 Isaiah 930-1014Enokman100% (1)

- The Role of The Lament in The Theology of The Old Testament"Dokument19 SeitenThe Role of The Lament in The Theology of The Old Testament"Abner ArraisNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02 Introduction To The PentateuchDokument8 Seiten02 Introduction To The PentateuchjgferchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prex SongsDokument4 SeitenPrex SongsAriane AndayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book of Proverbs: The Young and The RestlessDokument5 SeitenBook of Proverbs: The Young and The RestlessLahcen AkhoullouNoch keine Bewertungen

- SalaahDokument3 SeitenSalaahKm JmlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book of Mormon EvidencesDokument28 SeitenBook of Mormon EvidencesMoroni RolimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bio-Brian 22.11.2016Dokument33 SeitenBio-Brian 22.11.2016AndreaAnna100% (1)

- Creed PDFDokument1 SeiteCreed PDFNancy G. AndrewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Temples or High PlacesDokument3 SeitenTemples or High PlacesTemiloluwa Awonbiogbon100% (1)

- Prayer & WorshipDokument5 SeitenPrayer & WorshipCecilia Askew100% (2)

- Islamic Speech Review EXAMPLEDokument13 SeitenIslamic Speech Review EXAMPLESyukran SolehNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Bible and The Monuments, BoscawenDokument254 SeitenThe Bible and The Monuments, BoscawenDavid Bailey100% (1)

- Assignment 2Dokument2 SeitenAssignment 2Chimi ChangasNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Reasons On Why Does Allah Test UsDokument4 Seiten5 Reasons On Why Does Allah Test UshasupkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction Galatians Waggoner Against ButlerDokument1 SeiteIntroduction Galatians Waggoner Against ButlerpropovednikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Explorations of Memphite Theology - Compiled by Joan LansberryDokument2 SeitenExplorations of Memphite Theology - Compiled by Joan LansberrysovereignoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Three-Letter Word Outline and Sermon by Charles A. YawnDokument4 SeitenA Three-Letter Word Outline and Sermon by Charles A. YawnCharles A. YawnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Last 2 Ayat of Surah Baqarah (Translation, TranslDokument2 SeitenLast 2 Ayat of Surah Baqarah (Translation, TranslNadirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bhagavad Gita - FAQ'sDokument13 SeitenBhagavad Gita - FAQ'sapi-3699487100% (1)

- TayyamunDokument2 SeitenTayyamunpathan1990Noch keine Bewertungen

- Psalm 34 - Bible Commentary For PreachingDokument10 SeitenPsalm 34 - Bible Commentary For PreachingJacob D. GerberNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spiritual ExercisesDokument4 SeitenSpiritual ExercisesAnesia Baptiste100% (1)

- The Confusion of Amina Wadud and Islamic FeminismDokument3 SeitenThe Confusion of Amina Wadud and Islamic FeminismFirdause JesfrydiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internal or Self Claims Evidences of The Inspiration of The BibleDokument6 SeitenInternal or Self Claims Evidences of The Inspiration of The Bibleapi-26726627Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Origin of The Names of Angels and Demons The Extra-Canonical Apocalyptic Literature To 100Dokument12 SeitenThe Origin of The Names of Angels and Demons The Extra-Canonical Apocalyptic Literature To 100Oscar Mendoza Orbegoso100% (1)

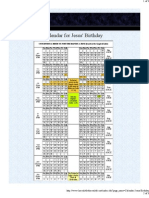

- Calendar For Jesus' BirthdayDokument3 SeitenCalendar For Jesus' BirthdayBryan T. Huie100% (1)

- Locate Covenant WealthDokument8 SeitenLocate Covenant WealthElishaNoch keine Bewertungen