Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

On The Black Swan Film

Hochgeladen von

MarielaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

On The Black Swan Film

Hochgeladen von

MarielaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This article was downloaded by: [Mariela Burani]

On: 19 February 2013, At: 20:18

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Culture, Theory and Critique

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rctc20

Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and

1

Becoming-Animal

Simone Bignall

Version of record first published: 03 Dec 2012.

To cite this article: Simone Bignall (2012): Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and Becoming-Animal ,

Culture, Theory and Critique, DOI:10.1080/14735784.2012.749110

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14735784.2012.749110

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation

that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any

instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary

sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,

demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or

indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Culture, Theory and Critique, 2012, 1 18, iFirst Article

Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and

Becoming-Animal1

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Simone Bignall

Abstract The film Black Swan, directed by Darren Aronofsky, provides a

fruitful context for thinking about Deleuzes conceptualisation of structural

transformation as a presubjective process involving a critical and creative politics of engagement. Nina is a young dancer who has just secured the lead role in

the New York Ballets new production of Swan Lake. This role not only requires

her to dance the pure and innocent character of the White Swan a role that

mirrors Ninas character in real life, and for which she is well suited but also

as the seductive and darkly erotic character of the Black Swan, a role quite

alien to Nina. The film traces Ninas desperate efforts to meet the demands of

this doubled characterisation. Through new forms of engagement with her

peers, she enters into a becoming-swan that frees her from the restraints and constraints imposed by her existing self. While this transformative process enables

her to realise aesthetic perfection in her art, this comes at a heavy price: Nina

not only is creatively destabilised, but ultimately is destroyed by the transformation she endures. By considering this work of cinema in light of Deleuzes writings on cinema, on becoming-animal, and on Porcelain and Volcano, this essay

reflects upon a crucial question underlying much of Deleuzes political thought:

how is it possible to privilege radical subjective and social transformation,

without these structures of necessary coherence also cracking up and being

destroyed in the process?

How are we to rid ourselves of ourselves, and demolish ourselves?

(Deleuze 1986: 66)

I wish to extend my gratitude to Teri Silvio and to two anonymous reviewers

who provided very helpful suggestions for revision. I also thank the conference organisers and participants of the 2010 Deleuze Studies Conference in Copenhagen, where

an earlier version of this paper was heard; my attendance at this event was made possible with financial support from the University of South Australia.

Culture, Theory and Critique

ISSN 1473-5784 Print/ISSN 1473-5776 online # 2012 Taylor & Francis

http://www.tandfonline.com

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14735784.2012.749110

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Simone Bignall

The 2010 film Black Swan, directed by Darren Aronofsky, images the complex

nature of relational identity and a process of radical transformation, a becoming, connected to a critical and creative politics of engagement. It issues an

affective invitation for the filmgoer to think about the phenomenological

process of identity construction, the experience of personal crisis and the ontological significance of the protagonists drastic psychological collapse and subjective reconfiguration. The central character of this film, Nina, is a young

dancer who has just secured the lead role in the New York Ballets new production of Swan Lake. This role not only requires her to dance the pure and

innocent character of the White Swan a role that mirrors Ninas character

in her real (filmic) life, and for which she is well suited but also the seductive

and darkly erotic character of the Black Swan a role quite alien to Nina. The

film traces Ninas desperate efforts to meet the demands of this doubled

characterisation. Through new forms of engagement with her peers, she

enters into a becoming-swan that frees her from the restraints and constraints

imposed by her existing self. While this transformative process enables her to

realise aesthetic perfection in her art, this comes at a heavy price: Nina not only

is creatively destabilised, but ultimately is destroyed by the transformation she

endures.

Deleuzes most sustained exploration of the relationship between film

and philosophy is presented in two books on cinema that use the Bergsonian

language of duration and of actual and virtual modes of existence to theorise

the movement-image and the time-image (Deleuze 1986, 1989; Mullarkey

2009). As Felicity Colman notes, when one is doing film-philosophy how

that conjunctive hyphen is practiced becomes indicative of a particular aesthetic and politic (2009: 3). By considering Black Swan as a movementimage and a time-image that can illustrate and illuminate wider aspects of

Deleuzian philosophy, which are often not well understood, this essay seeks

to expand new ways of thinking about processes of change. It situates a narrative description of Ninas transformation in relation to Series 22 on Porcelain

and Volcano in Deleuzes The Logic of Sense (2004), and in relation to Deleuze

and Guattaris (1987) writing on becoming-animal. This situating permits a

better understanding about how the incremental movement-image of

Ninas change additionally gives us a discontinuous time-image, in which

she moves through virtual intervals that separate moments of her actualised

being in present time. The essay reflects on a crucial question underlying

much of Deleuzes political thought: how is it possible to privilege radical subjective and social transformation, without these necessary structures of coherence also cracking up and being destroyed in the process? I conclude with a

brief reflection on the relationship between thought and film, and between the

movement-image and the time-image, in the case of Ninas becoming-swan.

Black Swan

The film begins with a mildly erotic dream sequence in which the protagonist,

Nina (Natalie Portman), is dancing as the virginal White Swan. In the dream,

she struggles to elude capture by a lecherous Black Swan who is extravagantly

costumed and sinisterly masked. Nina is a dedicated professional ballet

dancer in her twenties. She lives with her mother (Barbara Hershey) and

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and Becoming-Animal

they share a close, co-dependent relationship. Her mother babies Nina by

dressing her, feeding her and patiently pandering to Ninas egocentric ambitions and concerns. Nina appears like a fragile little girl, softly spoken, beautiful in a delicate way, perfectly coiffed and attired in pink and white, poised,

polished: insipid. In conversation with her mother, we learn she is desperately

hoping for the attention of her director, Tomas (Vincent Cassell), who has indicated he plans to feature her more in the coming performance season. In these

early scenes, we are also given a first clue that, despite her flawless demeanour, not all is perfectly well with Nina. After waking from her dream, she

notices a nasty, pricking rash emerging on the delicate skin of her shoulder,

which she hastily conceals from her mother.

Highlighting Ninas working life at the New York Ballet, the film shows

her arriving to a bitchy dressing-room and overhearing speculation that the

prima dancer, Beth, is to be replaced by someone younger who can revive

and rescue the company from its current decline. In the rehearsal space,

Tomas walks agonisingly slowly amongst the dancers, choosing or rejecting

them one by one as they practice, each subtly competing to be noticed and

picked. He narrates the story of Swan Lake, which will be the companys production for the new season, as he goes. This is the tale of a:

virgin girl, pure and sweet, trapped in the body of a swan. She

deserves freedom but only true love can break the spell. Her wish

is nearly granted in the form of a prince. But before he can declare

his love, her lustful twin, the black swan, tricks and seduces him. Devastated, the white swan leaps off a cliff, killing herself, and in death

finds freedom.

Tomas wants to make the production visceral and real; it will be original but

risky, because the same principal dancer will play the hugely demanding

double role of the White Swan, Princess Odessa, and her dark twin, Odile.

Nina is a graceful and technically accomplished dancer and is an obvious

choice for the part of the White Swan; but Tomas thinks she is too controlled

to play the role of the Black Swan, who must be unrestrained and able to

let herself go in desire. Nina, however, is desperate for the prima part,

which she has always dreamed of dancing. Arriving home that night, Nina

is anxious and despairing. She obsessively practices until her toenail is

cracked and bleeding from the constant strain of being en pointe. Her mother

comforts her and dresses her toe, puts her to bed like a little girl, and winds

her music box to lull her to sleep.

The next day Nina fortifies herself with lipstick secretly stolen from Beth

(the former prima-ballerina), and confronts Tomas, telling him she has practiced hard and deserves the part. He complains that she is too disciplined:

perfection is not only about control. Its also about letting go. Surprise yourself, so you can surprise the audience. He tests her by kissing her, and she

bites his lip in shock: while not a deliberate act of unfettered desire, this bite

is enough to convince Tomas to give her a chance. In joy, she hides in the

toilets to phone her mum: he picked me, mummy. As she walks away

from Tomas after the kiss, we again see the rash appear on Ninas back.

That night, the flesh is open, scratched and bleeding.

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Simone Bignall

Subsequent scenes trace Ninas ascension to prima-status and her efforts

to learn her part. As predicted, she finds the role of the Black Swan alien and

difficult, and Tomas is displeased. Nina is also threatened by the appearance of

a new dancer, Lily (Mila Kunis), whom Tomas has invited to join the company.

Lily is Ninas nemesis: she is casual with an easy sexuality. Tomas describes

Lilys dancing as imprecise, effortless; shes not faking it. While Nina is

plagued by insecurities, she relishes being the star at her debut cocktail reception as the prima dancer. However, in secret, she is increasingly falling apart

and we begin to understand that her mental state is dangerously strained.

Briefly escaping the reception by hiding in the ladies room, she worries at

her fingernail and then peels off a large strip of skin from her finger, exposing

a gaping wound. Immediately afterwards, her finger resumes its perfect form,

marking this breach of her surface boundaries as merely hallucination.

Obeying Tomas instructions to go home and live a little, Nina experiments with auto-eroticism as a way of loosening up. However, she finds

herself cloistered by her home environment: she is stifled by the remnants of

her extended childhood a pink bedroom crowded with plush toys; and

she is cosseted by her mother sleeping protectively on the chair in her room.

She cant let go in her mothers controlling domain, so she seeks privacy in

the bathroom with some success. In the moments of sexual arousal Nina

undergoes subtle transformations and momentarily loses her grip on reality.

In this instance, she hallucinates blood dripping into the water, then her fingernail bleeds and her back is covered in an ugly puckered rash that she worries

at. In sexual desire, she becomes porous and uncontained; she loses control

and her highly disciplined reality shifts, leaving her temporarily floundering

in a terrifying unreality.

Despite Ninas efforts to loosen up, her tightly measured dancing technique remains. Increasingly fearful of losing her prima-status, she begins an

ambivalent relationship with Lily, whom she jealously reviles and yet is

drawn to. She despises Lilys casual attitude to dancing and her sloppy technique, yet also knows that Lily personifies the unrestrained quality that Nina

herself must develop in her role as the Black Swan. Their relationship develops

dramatically when Lily convinces Nina to defy her mother and come out clubbing. Nina enjoys a wild night of dancing and drugs, which culminates in a

sexual encounter with Lily. In the act of sex, Nina and Lily share a mutual

becoming-swan. Lilys tattooed wings become feathered, while Ninas eyes

turn swan-red and her skin becomes goose-fleshed. Their bodies merge and

become indistinct in the encounter that transforms them. It is only when

Nina wakes alone in her room, which is barricaded from the inside, we

realise that Nina has hallucinated this night of sexual liberation and selftransformation.

From this point, Ninas self-composure rapidly declines. She arrives at

work to find that Tomas has made Lily her understudy she is paranoid

and convinced that Lily is out to replace her: shes after me . . . she wants

my role. Tomas reassures her, saying he thought Nina had had a breakthrough that morning when dancing the Black Swan. She increasingly

suffers hallucinations, which reflect her character-doubling and her forced

becoming: her reflection in the mirror fails to coincide with the reality of her

movements; rehearsing alone in the studio, she has visions of Tomas as the

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and Becoming-Animal

masked Black Swan from her dream, passionately engaged with Lily. She visits

Beth, who has been hospitalised after a self-inflicted injury, seeking to return

the things she had stolen from her and to receive Beths sympathy and understanding: I was just trying to be perfect, like you. However, Beth offers no

solace and mocks Ninas idolatry: Im not perfect: Im nothing, she says as

she stabs herself in the face Nina struggles to stop her, and then flees. The

viewer is unsure whether this incident is real or imagined, or indeed if Nina

is responsible: Nina is shown in the hospital lift clutching a bloodied nail

file. On returning home she hallucinates seeing Beth standing evilly in the

corner of the kitchen, then hears her mother crying. Going into her mothers

painting studio, the numerous portraits of Nina all turn ugly and start screaming and moving on the canvas. Nina tears them down in terror and disgust.

She barricades herself in her room, repeatedly and violently slamming her

mothers fingers in the door as she goes. She hallucinates her legs breaking

at odd angles and collapses, unconscious. The opening performance is the

following day.

In the morning, Nina wakes late and arrives at the studio in considerable

disarray, especially when compared with how poised and polished she was at

the start of the film. However, there is something more collected about her

demeanour. She calmly applies her makeup, and seems only mildly shaken

when she observes that her toes have become webbed, like a swans feet.

Tomas issues her with a final instruction to lose yourself: the only one standing in your way is you, and Nina takes the stage as the White Swan. But here

Nina again struggles to control her hallucinations; she misses the choreography and her partner drops her. Humiliated, she returns to her dressing

room to become the Black Swan but finds Lily is already there and

dressed for the part. They argue and scuffle, then Nina stabs Lily with a

shard from the mirror they have shattered. Its my turn, she hisses. She

hides Lilys body in the adjacent storeroom and calmly continues to apply

her makeup. Her eyes are swan-red, and her skin is gooseflesh. She pulls a

black feather from one of her pores. She takes the stage as the Black Swan.

Feathers erupt from her skin as she dances. She is a triumph. She returns to

her dressing room for the final costume change back to the White Swan.

Lily knocks on the door to congratulate her: Nina is confused Lily should

be safely dead in the storeroom. She checks and finds nobody there; no

blood seeping out from under the door. In sudden realisation, she looks

down at her own stomach, and sees that a bloodstain is blooming on the

white of her costume. The nemesis twin she had stabbed was her own self,

thus eliminating the innocent Nina and freeing the dark Nina to be a successful Black Swan. She returns to the stage, dances her final part perfectly, farewells her prince and the audience, leaps off the cliff and, just like the White

Swan, in death finds freedom. Tomas says: My little princess, I always

knew you had it in you. Nina says I felt it: I was perfect. And the film ends.

Montage produces an emergent Whole that captures the movementimage of Ninas transformation from one way of being to another (Deleuze

1986: 70); thus Black Swan images the destructive-creative processes of transformation. This focus similarly constitutes a crucial aspect of Deleuzes

work in general, which returns time and again to concepts of becoming,

actualisation and different/ciation, to theorisations of shifting movements

Simone Bignall

of de/reterritorialisation, to thinking about the affective processes constituting

and transforming bodies and identities, and so forth. While Deleuze and Guattaris conceptualisations of transformation certainly aim to generate motion

rather than to preserve stability, they frequently are sensitive to the radical disablement that can occur with a too rapid destabilisation of the structures that

identity relies on:

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

If you free it with too violent an action, if you blow apart the strata

without taking precautions . . . then you will be killed, plunged into

a black hole, or even dragged towards catastrophe. Staying stratified

organised, signified, subjected is not the worst that can happen;

the worst that can happen is if you throw the strata into demented

or suicidal collapse, which brings them back down on us heavier

than ever. (1987: 161)

By viewing Black Swan through a Deleuzian lens, this essay will consider how

the figure of Nina not only gives us a movement-image (which traces her

overall transformation from one state of actual being to another), but also a

time-image (which involves her in a different kind of transformation, involving moments of virtual (de-)identification). Together, these illustrate and conceptualise the two main concepts of process theorised by Deleuze and permit

improved understanding of them. In particular, I consider how transformative

processes may be understood to render movement possible while simultaneously retaining necessary coherence in the structures undergoing transformation. The following section considers Deleuzes theorisation of

transformation as a movement between actual and virtual states of being,

investigated here in a reading of the Twenty-Second Series of The Logic of

Sense (Porcelain and Volcano). The subsequent section discusses transformation as the result of affective relations between bodies, investigated here

through a reading of Deleuze and Guattaris concept of becoming-animal.

Porcelain and Volcano

In the Twenty-Second Series of The Logic of Sense, Deleuze explores the corporeal effects of the transformation that occurs when the virtual and the actual

coincide, or when an individual seeks to make virtual and actual realities

coincide, to produce an alternative version of the self. He notes that there

are various ways to bring about this association suicide or madness, the

use of drugs or alcohol (2004: 178) each having a radically transformative,

yet ultimately negative, effect on the individual who cracks up. For Deleuze,

the crack is a sign of the interface between the virtual and the actual: the

crack is neither internal nor external, but rather is at the frontier. It is imperceptible, incorporeal and ideational. With what happens inside and outside, it has

complex relations of interference and interfacing (177).

As upon a dropped plate, external pressures can induce a fissure to

appear and spread upon a surface, but often this surface event portends a

deeper change; an event of radical transformation at which time the plate

will break and cease to exist as such. Accordingly, for a surface event or

impact to have a radically transformative effect on a body, Deleuze suggests

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and Becoming-Animal

that it must wend its way down to something of a wholly different nature

the silent crack (176). Various image of Ninas cracked surface recur throughout Black Swan. In promotional posters, where her porcelain face is split by a

deep fracture, the imagery of the crack is an obvious and undisguised metaphor of psychological trauma. The film also makes use of more subtle and

prosaic imagery such as broken and bleeding toenails and a skin rash to

convey the idea that Ninas structural boundaries are unstable and shifting.

The rash on Ninas shoulder appears as the material effect of Ninas stressful

affective relationships with her work, with the masculinist and highly restrictive options for gender-identification that she is expected to embody and move

between, with her peers and with her own feelings of inadequacy and ambition. It appears like a pressure crack on her surface; however, it also signals

some deeper transformation in process. The rash not only is a surface effect

produced by Ninas relationships with actual entities and situations; it is

also a physical change that emerges from her engagement with a virtual self

and a virtual world. Deep inside, Nina is undergoing subjective changes as

her actual self confronts the virtual potential that she must draw upon in

order to meet the challenges of her new role. Ninas experience of self-transformation exemplifies Deleuzes suggestion that, in processes of change,

there are two elements or two processes which differ in nature . . . there is

the crack which extends its straight, incorporeal, and silent line at the

surface; and there are external blows or noisy internal pressures which

make it deviate, deepen it, and inscribe or actualise it in the thickness of the

body (178).

Here, Deleuze is insisting on a complex relationship between virtual and

actual causes of transformation, which necessarily must coincide within an

existing structure in order to bring about a genuine change in its nature. Had

Ninas rash remained a simple surface effect of her stressful encounters a

material sign of her situation in the world of the New York Ballet she

would have remained essentially the same limited character: a White Swan,

but with a rash. In order to extend the existing territory of her identity and

take on the role of the Black Swan, Nina had to engage in a process of radical

becoming that drew her into a new proximity with virtual forces of identity-formation. She needed to access alternative sources of self, different forces of desiring-production. To play her new role convincingly, she was required to expand

her existing self and her established modes of materialisation as an innocent

little girl with productive desires mainly defined in relation to her mother.

She struggled to counteractualise this existing and entrenched self by exposing

it to alternative forces of desire, in particular to new experiences of sexual

desire. By enacting these new modes of desire and seductive association

(with Lily, with Tomas), she was able to reactualise a new form of self: the

Black Swan. Thus, Ninas transformation in nature would be nothing

without the virtual force of desiring-production that dissolves her existing

form; but equally, the virtual Black Swan would be nothing, had Nina not

been able to incarnate alternative virtual desires in a reactualised or recomposed form of identity (177). In Nina, virtual forces and actual forms necessarily

coincided to produce changes in her nature, culminating in her new identity as

the Black Swan. In Nina, the entire play of the crack has become incarnated in

the body (177).

Simone Bignall

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Ninas aesthetic perfection as the Black Swan illustrates Deleuzes claim

that it is only by means of the crack and at its edges thought occurs, that

anything that is good and great in humanity enters and exits through it

(182). However, if transformation is not to remain virtual, and therefore

abstract and ridiculous (178), relegated to the realm of speculation or of

what could have happened, the surface crack must be incarnated with

actual effects on the embodied self: crack remains a word as long as the

body is not compromised by it (182). And yet, as Nina also illustrates, to

compromise oneself in order to experience the wound of the virtual Event

requires one to court danger, to be mad or alcoholic, to risk something

perhaps even ones very existence. Thinking about the implications of this

conundrum is the primary concern of this Series of the Logic of Sense.

Deleuze asks:

If the order of the surface is itself cracked, how could it not itself break

up, how is it to be prevented from precipitating destruction . . .. If

there is a crack at the surface, how can we prevent deep life from

becoming a demolition job . . .. Is it possible to maintain the inherence

of the incorporeal crack while taking care not to bring it into existence,

and not to incarnate it in the depth of the body? More precisely, is it

possible to limit ourselves to the counter-actualisation of an event to

the actors or the dancers simple flat representation while taking

care to prevent the full actualisation which characterises the victim

or the true patient? (1789)

While Deleuze returns to this crucial problem at many moments in later

work to offer increasingly sophisticated solutions, here he merely sketches

the contours of the approach he will develop. Accordingly, at this point, he

gives a fairly unsatisfying answer to the questions he poses. He begins by

asserting that in processes of self-transformation that rely upon the fact of

having risked the established self, of having become undone in order to set

the self in motion, the subject simultaneously embodies a present existence

as well as a past-present existence. She is the effect of an I have-drunk; or

in Ninas case, the effect of an I have seduced, an I have been sexual. The

transformed Nina emerges at the moment when she identifies as the effect

of the effect (181). In dancing the Black Swan, she becomes the actualisation

of that virtual state of being she had experienced at defining moments

throughout the film. In those moments, her sexual arousal or madness were

the effects of her letting go and losing her frigid identity, and indeed in

such moments she became momentarily other than her usual self. As she performs the Black Swan to perfection in the final scene of the movie, Nina is the

emergent effect (or actualisation) of a virtual effect (her sexualised self). She is

an actual embodiment of a subject who identifies as the effect of the effect of

her destabilisation through her engagement with the virtual: she is at once

object, loss of object, and the law governing this loss within an orchestrated

process of demolition (182). At this moment, in which actual self and

virtual self coincide, Nina achieves a perfect summit of identification, at

which point she breaks like a glass (181).

Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and Becoming-Animal

Like Gatsby, where Nina goes wrong is that she fails to accompany

herself in this radical transformation through her encounter with a virtual

existence. Deleuze writes:

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

the eternal truth of the event is grasped only if the event is also

inscribed in the flesh. But each time we must double this painful

actualisation by a counteractualisation which limits, moves and transfigures it. We must accompany ourselves first, in order to survive,

but then even when we die. (182)

By this, he means that one must remain connected to the actual forms that constitute identity, even as one must let go of the safe shore of the self in order to

voyage into the virtual ocean of chaotic desiring-production. Rather than

extending the existing territory of her identification with the White Swan to

also become the Black Swan, Nina wholly abandons her little-girl self and

replaces this identity with an erotic alter-ego. For Nina, the White Swan and

the Black Swan are mutually exclusive actualisations of self; she fails to

accompany herself and to be both at once. Her embodiment as the Black

Swan entails the death of her existence as the White Swan, and ultimately of

Nina herself.

When Deleuze asks, how are we to stay at the surface without staying on

the shore? How do we save ourselves by saving the surface and every surface

organisation, including language and life? (179), he does so in order to assert

the foolishness of perspectives that insist we should choose virtual creativity at

the expense of the actual forms that sustain us and give us coherence. In fact,

as the example of the crack illustrates, a self in motion is never actually fixed or

virtually fluid, but always a combination of both. The crack is the sign of a

transformation in process: it is a complex interface of virtuality and actuality;

it is neither one nor the other, but is simultaneously actual and virtual, material

and incorporeal. The example of the crack allows Deleuze to demonstrate that

the virtual and the actual must be thought together for transformation to be

comprehensible at all. Failing to maintain a connection between the two,

between the actual self that exists and the virtual selves that are the causal

source of ones becoming, one ceases to be. Ninas error was to follow absolutely Tomas instruction to lose herself. She lost all her actual moorings in

her extreme act of self re-creation, replacing her identification as the White

Swan with that of the Black Swan; in failing to accompany herself through

the trauma of destabilisation and so to anchor herself through the process of

change, and unable to survive as a virtual and chaotic entity, she finally

ceased to exist at all.

For Deleuze, to travel into the unsettled, virtual realms of non-being is an

essential step in any process of creative transformation that seeks to create new

forms of existence: to the extent that the pure event is each time imprisoned

forever in its actualisation, counteractualisation liberates it, always for other

times (182). However, successful processes of counteractualisation take

place only in connection to an existing and problematic actuality or to new

movements of actualisation, which can sustain the shifting or newly created

structure and partially preserve its consistency and coherence even as it transforms. For Deleuze, this doubling of the newly created self with the self that is

10

Simone Bignall

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

lost in transformative movements is the vital key to orchestrating creative

transformation that will not simply end in destruction or death. He writes:

We cannot give up the hope that the effects of drugs and alcohol [or

madness] . . . will be able to be relived and recovered for their own sake at

the surface of the world (1823). We must hope that the creative and transformative effects of virtual forces that decompose and recompose structures can

be experienced in the world, albeit at the very surface of the world, at those

uncertain places where identity shifts and morphs; we must hope that to

experience radical self-transformation or to reach the aesthetic perfection we

desire, does not entail that we must depart the world because only in death

[will we] find freedom. While it remains underdeveloped here, this line of

thinking is pursued in a much more satisfying way in A Thousand Plateaus

(1987) with the theorisation of affective becomings.

Becoming-swan

Despite her initial efforts to imitate the prima-ballerina Beth by stealing her

lipstick and appropriating her role, Nina quickly is swept up by a becoming-animal not content to proceed by resemblance and for which resemblance,

on the contrary, would represent an obstacle or stoppage (Deleuze and Guattari 1987: 233). Deleuze and Guattari are careful to insist that, in their theorisations of transformation, processes of becoming are not directed towards

identification with an ideal or an end point. For them, A becoming is not a correspondence between relations, but neither is it a resemblance, an imitation, or

at the limit, an identification (237). In movements of becoming, one does not

evolve towards an identity; instead, becoming is a movement that happens

between identities and beneath assignable relations (239). Accordingly,

becoming concerns alliance (238) but not of an idolatry or identifying

sort: becoming is certainly not imitating, or identifying with something

(239). Ninas becoming-swan transformed her identity, but the process of

her transformation did not take place through her efforts to be like Beth or

Lily, or to be the Black Swan. In fact, Tomas complains she is unconvincing

and wooden in her attempts to mimic the Black Swan. Rather, the process of

her transformation takes place through the unstable alliances that remain

beneath her subjective control and do not involve a deliberate act of identification. Ninas becoming-swan takes place in the shifting affective connections

between Nina and the other characters in the film: most particularly in her

changing relationships with her mother, with Lily and with Tomas.

In order to understand adequately what is involved in becoming,

Deleuze and Guattari explain that it is necessary to conceptualise the individual as a multiplicity. In fact, their emphasis on the multiplicity of the individual form is the reason why they attach such significance to the notion of

becoming-animal, since every animal is fundamentally a band, a pack

(239). Becoming-animal always involves the individual form rediscovering

its existence as a multiplicity: it is at this point that the human being encounters the animal. We do not become animal without a fascination for the pack,

for multiplicity (23940). In order to understand this crucial point, it is helpful

to remember that Deleuze and Guattari rely upon an ontology of emergence:

individuals appear as ordered forms of being when the virtual forces between

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and Becoming-Animal

11

the elements that compose them take on regular or habitual forms. However,

this appearance of order in the actualised form belies its true complexity and

fluidity; it is truly an unstable composition of elemental relations, contingently

bound into a coherent structure. The individual is a multiplicity because it is

an assemblage of elemental parts, arranged in complex relations. Some of

these elemental relations are internal to the individual, while some are

shared in common with neighbouring individuals and external structures.

For example, if we consider Nina to be a complex multiplicity, we will understand that she is defined by the elemental parts that compose her: dancing,

music box, shyness, broken toenail, ambition, frigidity, plush toys, being mothered, determination, obsession, and so forth. Nina emerges as an effect of the

connections forged between these elemental features, which combine to form a

contingently stable character, recognisable as Nina. However, the external

relations she forms with the individuals she encounters in her world also

define Nina: her mother, Lily, Beth, Tomas. Nina is therefore a complex multiplicity composed not only from the internal relations between elemental

parts that over time have come to define her interior character, but also from

the external relations she engages. Each elemental combination that defines

her can be considered a haecceity, an event of connection, that enters into composition with others to form an other individual (253). And Nina is herself a

haecceity, an event of composition that combines with others in external

relationships to form new and more complex forms of order for example,

a dance company.

Conceiving of Nina as a complex multiplicity, an emergent form defined

by complex and shifting relationships between elemental parts, allows us to

understand that even at the start of the film when she appears coherent and

rigidly characterised, and she is quite strictly identified with the White

Swan, in fact this apparent fixity is illusory. Like all forms of emergent

order, Nina is always-already subtly undergoing transformations at the microlevel; these transformations occur between the elemental relations that she

shares with others and which compose her, and thus also beneath the coordinated form of complex individuality that centres her awareness as a subject.

Deleuze and Guattari explain:

in short, between substantial forms and determined subjects, between

the two, there is not only a whole operation of demonic transports but

a natural play of haecceities, degrees, intensities, events and accidents

that compose individuations totally different from those of the wellformed subjects that receive them. (253)

Every time one of her composing relationships shifts for example when she

throws her toys out, or defies her mother, or when Lily joins the New York

Dance Company and becomes a new element in Ninas life there occurs

in Nina a flutter, a vibration in the form itself that is not reducible to the properties of a subject (253). While these shifts in some of her affective relations at

the microlevel do not necessarily result in the radical transformation of Nina,

they do produce the partial and piecemeal morphing of her identity. Some of

her elemental relations change even while others remain stable, giving Nina a

characteristic consistency at least in the early stages of the film.

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

12

Simone Bignall

Ninas becoming-swan noticeably begins when she starts to be confronted

with images of herself as a multiplicity seething beneath the apparent unity of

her coherent self. The rash of inflamed pores on her shoulder evidences the

actual cellular multiplicity of her skin, which usually appeared to be a flawless

and unified boundary between her and the world. In the bathroom at her

debut reception, she peels back the skin of her finger to reveal a gaping

wound, a hidden cellular depth. Deleuze and Guattari suggest that in a

way, we must start at the end: all becomings are already molecular (272)

and you become animal only if, by whatever means and elements, you emit

corpuscles that . . . enter the zone of proximity of the animal molecule. You

become animal only molecularly (275). The existence of this hidden molecularity within Nina was the condition for her becoming-animal: animals are

packs, and . . . packs form, develop, and are transformed by contagion (244);

they continually transform themselves into each other, cross over into each

other (249). They do so because their composing parts combine, break form,

and recombine in complex patterns of molecular interaction.

However, becoming-animal does not only involve the dissolution of the

individual into its internal elements, its composing molecular parts, but also

proceeds by way of a special alliance with an exceptional individual (243).

The alliance with the exceptional individual is a phenomenon of bordering

(245) and of assemblage; in entering into new relations with others, the individual forges new complex connections, taking into the existing self new

elements introduced with the new relationship. Deleuze writes: multiplicities

enter certain assemblages; it is there that human beings effect their becominganimal (242). In Ninas case, her becoming-swan proceeds particularly

through her important new relationship with Lily, forged in the context of

her new role dancing as the Black Swan. Lily introduces Nina to new experiences: clubbing, drugs, defiance. These become new dimensions of selfhood

that combine with her existing form to destabilise and transform the composition that is Nina. Parts of Lily combine with parts of Nina; this is the

sense in which becoming is the process of desire (272), and sexuality is the

production of a thousand sexes, which are so many uncontrollable becomings

. . . an emission of particles (2789). In their new proximity, Lily affects Nina

but not in entirety. Nina is affected at the molecular level, bit by bit, as parts of

her existing form combine in new and unexpected ways with parts of Lily.

Initially, her involvement with Lily transforms Nina in minor and imperceptible ways: a feeling of jealousy, a puff of Lilys cigarette. But increasingly Nina

is destabilised through the affects provoked by her encounter with Lily. For

Nina, the affect is not a personal feeling, nor is it a characteristic; it is an effectuation of a power of the pack that throws the self into upheaval and makes it

reel (240).

Some feeling of vertigo or upheaval is perhaps inevitable in the destabilising processes of becoming. Deleuze and Guattari comment: who has not

known the violence of these animal sequences, which uproot one from humanity, if only for an instant . . . giving one the [red eyes of a swan]? (240).

However, Ninas transformation ultimately is radically disabling, not only compromising her subjective experience of herself and the comfort of her worldly

belonging, but finally destroying her bodily form in injury and death. Becomings are unpredictable; we dont know in advance how multiplicities will

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and Becoming-Animal

13

combine. They may combine in mostly positive ways that overall add new

dimensions of complexity and richness to the existing individual; but a

meeting of multiplicities might alternatively diminish or destroy one or

both, if too many of their elemental connections are incompatible. Deleuze

and Guattari point to two dangers associated with becoming-animal: on the

one hand, the process may be stifled by the capturing of new forces and

their reterritorialisation by existing forms; the second occurs when the

process is so disruptive of ones existing set of affective relations that one

spirals into a line of abolition. Because we do not know in advance how

becoming will transpire, Deleuze and Guattari insist we must proceed cautiously, we must experiment according to criteria: there are criteria, and

the important thing is that they not be used after the fact, that they be

applied in the course of events, that they be sufficient to guide us through

the dangers (251; see also 160ff).

What, then, are these criteria that might safeguard the self through its

creative becoming-animal? I think we can identify two. The first is to engage

molecular becomings at the complex affective surfaces where bodies meet,

rather than wholesale molar transformations that completely undo an existing

form of identity and seek to replace it with another. Because transformation is

relational, the clue to preservation of consistency lies in the piecemeal and

partial nature of relationships. It is always possible to selectively engage multiple relationships and to meet with others bit by bit, in partial and selective

ways, to make piecemeal insertions into each others lives, rather than to

wholly succumb to anothers will or to attempt to wholly dominate another

(Deleuze 1990: 237; Deleuze and Guattari 1987: 504). To conceive of this possibility requires one to consider oneself, not as a unified and stable entity, but as

a multiplicity, a pack: a transient and morphing, though relatively consistent,

form of identity composed of elemental parts arranged in complex internal

and external relations. Nina was not able to do this; rather than welcoming

her molecular self as the creative key to partial and selective transformations

that could assist her to become the Black Swan, Nina did her best to deny, discipline and repress the evidence of her true multiplicity (which nonetheless

surfaced repeatedly and insistently: her doubled reflection in the mirror, her

porous rash). Rather than welcoming an inner complexity and fluidity that

could allow her flexible accommodation of the new forms of identification

she needed in order to take on the role of the Black Swan while also retaining

the characteristics and relations that made her perfect for the White Swan,

Nina struggled through a wholesale transformation. She sought to entirely

reject one identity and the set of mother-daughter relations it depended on,

and replace it with an entirely different one built from a new set of relations

with Lily. Ninas becoming was sudden and catastrophic: not piecemeal and

selective, proceeding carefully and experimentally, but clumsy and radical.

She could not develop a relationship with Lily except by wholly abandoning

her relationship with her mother; her final triumph as the Black Swan could

not be accomplished without her failure as the White Swan.

Careful experimentation with ones relationships at the molecular level of

engagement allows one to learn what the body can do for example,

whether it is capable of dancing as the Black Swan and as the White Swan,

or how it might combine with surrounding elements to compose an individual

14

Simone Bignall

that is capable of doing so (Gatens 1996). Referencing Spinoza, Deleuze and

Guattari write:

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

we know nothing about a body until we know what it can do, in other

words, what its affects are, how they can or cannot enter into composition with other affects, with the affects of another body, either to

destroy that body or to be destroyed by it, either to exchange

actions and passions with it or to join with it in composing a more

powerful body. (257)

Learning about the capabilities and capacities of the relational self requires a

constant vigilance concerning actual embodiment and, simultaneously,

careful attention to the creative virtual potential associated with the forms

one might yet produce through new compositions. This, then, alerts us to

the second criteria needed for creative becomings that can sustain a self

through transformation. In becoming, one inhabits a plane of consistency,

which is not best conceived of as pure chaos or the point at which order has

been counteractualised into a pure form of virtual potential. Rather, while

the plane of consistency, in itself, is virtual and immanent to actual forms of

order, it is also the intersection of all concrete forms (251) in a zone of proximity. To inhabit the plane of consistency is not to dissolve in virtual non-existence, but to experience the complex actuality of existence, as a relational

multiplicity that potentially intersects with diverse others in a zone of affective

proximity. Thus, inhabiting the plane of consistency, one is simultaneously

actual and virtual; both embodied in an ordered form and shifting at the

uncertain points of contact where actual individuals meet and virtual individuals are being formed. This complex co-existence of actual and virtual being

characterises multiplicities, which are by their nature becomings. Through

cautious experimental learning what the body can do in its affective encounters, individuals may come into selective contact at the molecular sites of their

engagement, and they may then partially transform one another, without

being destroyed in the process.

Conclusion: movement-image, time-image and affect-image

An expanding field of inquiry links film with philosophy. For some, this link

takes the form of an illustrative methodology through which cinema furnishes

material for philosophical investigation; for others, film is a thinking (Frampton 2006: 193; Sinnerbrink 2011; Tuck and Carel 2011). For us, Black Swan does

both. While it is clear that this film provides content for the philosophical

analysis we have engaged, it is perhaps less obvious how it is a thinking.

What are the qualities of (this) film that give it a capacity for conceptual

activity? In his two books on cinema, Deleuze explains that film has a

special relationship with thought because it is capable of constructing a movement-image and a time-image, each of which constitute shocking ideas of an

unthinkable Whole that forces the becoming of thought (1989: 158; Flaxman

2000).

We have seen how Black Swan images the movement of Ninas transformation as she passes from the poised and polished dancer at the start of

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and Becoming-Animal

15

the film, through various stages of crisis and undoing, to her final perfection

and death. The movement-image describes the actual progression of Ninas

transformation: her embodiment of various actualisations of being, which

incrementally shift her through a process of change that is ultimately radical

and destructive. The camera images this movement from a perspective external to Nina. We (as the camera) watch her from a position nearby: on the

train, practicing in the studio, talking with her mother, drinking in the nightclub, and so forth. From this outside perspective, the camera depicts Nina

through various moments of actual existence, which are linked together

through montage to create an emergent picture of Ninas overall transformation from one state to another: to describe is to observe mutations

(Deleuze 1989: 19). In this way, the developing story of the film creates an

image of a Whole the overall movement of Ninas transformation which

is itself a concept of movement over time. While narrative is a descriptive

device shared across artistic forms, the movement-image is particular to

cinema in the way that it connects static images to movement by linking

them in series, and subsequently by connecting series to a moving Whole

via the cinematic technique of montage; it is through the movement-image

that cinema thinks the actual nature of processes, and that we have the

idea of the film (1986: 179).

However, Black Swan additionally constructs a time-image, which does

not simply correspond to the realm of actual figures, their shifting relations

and our perceptions of the characters as they transform and so produce the

story of the film, but properly extends into a virtuality that can only be conveyed by images of hallucination, such as mirror-doubling and molecularity

(Deleuze 1989: 70). The time-image is virtual, in opposition to the actuality

of the movement-image (41). Indeed, for the time-image to be born . . . the

actual image must enter into relation with its own virtual image . . .. An

image which is double-sided, mutual, both actual and virtual, must be constituted (273). Accordingly, unlike the external camera shots that convey to us

Nina in her actuality, the camera images this realm of virtual existence from

a perspective internal to Nina. Through her eyes, we see the troubling rash

on our shoulder; we observe, from Ninas perspective, the skin peeling

back from our finger to expose the seething molecular depth within; we

stand in Ninas position before the studio mirror to see our reflection slide

into a menacing doubling of figures that haunts us. Increasingly, Aronofsky

interjects these images of virtual existence between shots of Nina carrying out

her actual activities until, in the final scenes of the film (following Ninas incessant hallucinations the evening before the opening-night performance),

we no longer know what is imaginary or real, physical or mental, in

the situation, not because they are confused but because we do not

have to know and there is no longer a place from which to ask.

(Deleuze 1989: 7)

In this way, Black Swan creates a time-image that is, like the movement-image,

an image of a Whole. However, because it encompasses not only actual beings

but also incomprehensible depths of virtual existence, this Whole is a more

profound unity, immense and terrifying, like a universal becoming (115).

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

16

Simone Bignall

The time-image reveals the coexistence of sheets of past and the simultaneity

of peaks of present (101), and transformation is revealed as a movement

between actual or present states by means of virtual engagement. The timeimage is cinemas special contribution to thought. With the time-image of

Ninas complex existence as simultaneously actual and virtual at once

past, present and future the viewer is confronted by something unthinkable

in thought (169). Black Swan shows us the impossible and inexpressible

concept of being in time as universal becoming.

There is at least one other way in which Black Swan thinks transformation, and this is by way of the affect-image, which is in fact implicated in

the construction of both the movement-image and the time-image. Deleuze

describes the affect-image as quality or power, it is potentiality considered

for itself as expressed (1986: 98). The cinematic technique of the close-up

shot corresponds particularly with the affect-image (1986: 98103). As we

have seen, affection is a crucial dimension of becoming-animal, which proceeds in partial and piecemeal fashion through complex molecular engagements between neighbouring bodies when they come into close-up contact.

Black Swan is a fine example of a cinema of the body (Deleuze 1989: 189).

Throughout the film, we are confronted by close-up images of bodies in

extreme states of physicality and discomfort: the gruelling rehearsal regime;

Ninas broken toenail; her angry rash and gooseflesh; Lily and Nina entwined

in the act of sex. The close-up shot and the affect-image is, for Deleuze, another

form of the cinematic shock that prompts thought. In the case of the affectimage, the thought that is provoked is the idea of relationality. This is an

idea of what happens to bodies in close proximity, which touch each other

and transform each other in the process of their encounter. It can include the

relation between actual images in sequence, or series of actions created by

the techniques of cutting employed by the director, or interaction between

characters and situations, or the relation between the image and the viewer.

However, the affect-image, in its expressed potentiality, is also an image of

the virtuality experienced in encounters, when they draw bodies into shared

becomings as they combine and transmit parts. For example, by juxtaposing

affective imagery of the unstable molecularity of Nina her rash, her

doubled reflection with affective imagery of her complex and uneven

relationships, which are revealed through dialogue and scene-situations in

which she is combined with other characters, Black Swan thinks the ways

in which Nina is affected when she enters into partial relations at particular

sites of elemental engagement. The film images the ways in which Ninas

complex affections at once enable, constrain and force the process of her transformation. Through the affect-image, which combines virtual forces and actual

forms of relational embodiment, we learn what Ninas body can do: we can

imagine what it is capable of doing and how it may (or may not) combine

with neighbouring bodies to produce new kinds of affective subjectivity for

Nina. This concept of relational becoming is properly philosophical, but is presented in film through the affect-image.

Through the movement-image, the time-image and the affect-image,

cinema unconceals the real world by rethinking a film-world (Frampton

2006: 193). As a philosophical activity, the political nature of a film is determined by the ways in which its concepts are gathered to produce a particular

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Black Swan, Cracked Porcelain and Becoming-Animal

17

effect: the filmic event may simply reflect and illuminate a worldly reality,

but may also or alternatively create images affecting viewers who may

become redirected in our aesthetic awareness of the critical and qualitative

dimensions of the world (Colman 2009: 14; Cox 2011). Film has a special

relation with the brain, with thought, in so far as it opens up, within the

innermost reality of the viewer, a fissure, a crack (Deleuze 1989: 167);

this crack reveals a virtual world with the capacity to sweep actual

worlds, real worlds, into processes of becoming-otherwise. It is especially

in its capacity to create the virtual time-image that film displaces our

world, and shows us another world (Frampton 2006: 202), which projects

the possibility of unsettling certain established patterns of thought and disturbing some entrenched configurations of the real (Deleuze and Guattari

1994). The conceptual scaffolding of a present actualisation thus being partially revealed and selectively undone, the thoughtful filmgoer may potentially think concepts anew, carefully reassemble them to form new

philosophical understanding, and so begin to creatively enact the world

and invent the practices of worldly being and virtual becoming that Deleuzian philosophy endeavours to think.

References

Aronofsky, D. 2010. Black Swan. Los Angeles: Fox Studios.

Colman, F. 2009. What is Film-Philosophy?. In F. Colman (ed), Film, Theory and

Philosophy: The Key Thinkers. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 119.

Cox, D. 2011. Thinking through Film: Doing Philosophy, Watching Movies. London: WileyBlackwell.

Deleuze, G. 1986. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Translated by H. Tomlinson and

B. Habberjam. London: Athlone.

Deleuze, G. 1989. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Translated by H. Tomlinson and R. Galeta.

London: Athlone.

Deleuze, G. 1990. Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza. Translated by M. Joughin.

New York: Zone Books.

Deleuze, G. 2004. The Logic of Sense. Translated by M. Lester with C. Stivale. New York:

Continuum.

Deleuze, G., and Guattari, F. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia,

Volume 1. Translated by B. Massumi. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

Deleuze, G., and Guattari, F. 1994. What is Philosophy? Translated by G. Burchell and

H. Tomlinson. London and New York: Verso.

Flaxman, G. 2000. The Brain is the Screen: Deleuze and the Philosophy of Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Frampton, D. 2006. Filmosophy. London and New York: Wallflower Press.

Gatens, M. 1996. Imaginary Bodies: Ethics, Power and Corporeality. London and

New York: Routledge.

Mullarkey, J. 2009. Gilles Deleuze. In F. Colman (ed), Film Theory and Philosophy: The

Key Thinkers. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 17990.

Sinnerbrink, R. 2011. New Philosophies of Film: Thinking Images. London & New York:

Continuum.

Tuck, G., and Carel, H. (eds), 2011. New Takes in Film-Philosophy. New York and

London: Palgrave MacMillan.

18

Simone Bignall

Downloaded by [Mariela Burani] at 20:18 19 February 2013

Simone Bignall is Vice-Chancellors Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Philosophy at

the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. She is the author of Postcolonial Agency: Critique and Constructivism (2010), which conceptualises postcolonial transformation in terms of Deleuzes philosophy of difference and desire. She is also

co-editor of Deleuze and the Postcolonial (2010) with Paul Patton and of Agamben and

Colonialism (2012) with Marcelo Svirsky, all published by Edinburgh University Press.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

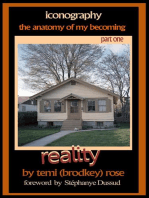

- Reality: Iconography: The Anatomy of My Becoming, #1Von EverandReality: Iconography: The Anatomy of My Becoming, #1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Occult Black SwanDokument193 SeitenOccult Black SwanjedimanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mythical Metamorphosis in Black Swan (2010) Ayşegül YAYLADokument7 SeitenMythical Metamorphosis in Black Swan (2010) Ayşegül YAYLARizwana RahumanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis Beauty BeastDokument6 SeitenAnalysis Beauty BeastLiam DoddsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black Swan 2010Dokument3 SeitenBlack Swan 2010smallbrowndogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Película "Black Swan"Dokument3 SeitenPelícula "Black Swan"YeffersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freak Shows, Spectacles, and Carnivals Reading Jonathan Demme's BelovedDokument15 SeitenFreak Shows, Spectacles, and Carnivals Reading Jonathan Demme's BelovedDiego Fernando GuerraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answers To Boy Girl WallDokument7 SeitenAnswers To Boy Girl WallSteven Truong100% (3)

- Intersections - EsseyDokument6 SeitenIntersections - EsseynikolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jacques Tourneur's Cat People (1942) and PsychoanalysisDokument10 SeitenJacques Tourneur's Cat People (1942) and PsychoanalysisSu Langdon100% (1)

- Creating Interiority in Black SwanDokument9 SeitenCreating Interiority in Black SwanDig Ity100% (1)

- Inside NEXT TO NORMAL by Scott MillerDokument20 SeitenInside NEXT TO NORMAL by Scott Millerian galliganNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Perspective: Ariel, Medea & Black SwanDokument9 SeitenIn Perspective: Ariel, Medea & Black SwanDig ItyNoch keine Bewertungen

- DRM220 Final TestDokument6 SeitenDRM220 Final TestNinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Young CaptstoneDokument24 SeitenYoung Captstoneapi-252674728Noch keine Bewertungen

- Academic ReportDokument5 SeitenAcademic ReportSara AndrejevićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meet Joe Black (1998) : A Metaphor of LifeDokument10 SeitenMeet Joe Black (1998) : A Metaphor of LifeSara OrsenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sweeney Todd and The Phantom of The Opera. Fear Has Even Been Raised Throughout Child's MoviesDokument2 SeitenSweeney Todd and The Phantom of The Opera. Fear Has Even Been Raised Throughout Child's MoviesDarigan194Noch keine Bewertungen

- Deception EssayDokument5 SeitenDeception Essaykingkola36Noch keine Bewertungen

- Exam Question Pans LabDokument1 SeiteExam Question Pans LabDanushke KarunarathneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inside Next To NormalDokument14 SeitenInside Next To NormalSamyson AguileraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annotated BibliographyDokument2 SeitenAnnotated BibliographyElena PetrovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On The Short Story Mom Luby and The Social WorkerDokument2 SeitenNotes On The Short Story Mom Luby and The Social Workermtheobalds17% (6)

- Black SwanDokument6 SeitenBlack Swanderaj1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Uta HagenDokument35 SeitenUta HagenLarissa Saraiva75% (8)

- Sponsorship ProposalDokument35 SeitenSponsorship ProposalCalum MowattNoch keine Bewertungen

- FinalDokument10 SeitenFinalMelissa GPNoch keine Bewertungen

- Horror Genre PosterDokument4 SeitenHorror Genre Posterapi-273816958Noch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Textural AnalysisDokument8 SeitenComparative Textural AnalysisLIAMMANKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black Swan AnalysisDokument16 SeitenBlack Swan AnalysisDanielle MarquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black Swan Is One of The Most Popular Drama Movies of FoxDokument14 SeitenBlack Swan Is One of The Most Popular Drama Movies of FoxCon SletNoch keine Bewertungen

- LAST SUMMER (Press Kit)Dokument22 SeitenLAST SUMMER (Press Kit)Ricardo DávalosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cat People: by Chuck BowenDokument2 SeitenCat People: by Chuck BowenAhmed ArifNoch keine Bewertungen

- FNL Analysis.Dokument12 SeitenFNL Analysis.bayani balbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Based On The Nature of The Film Language and The Film "The Purple Rose of Cairo"Dokument2 SeitenBased On The Nature of The Film Language and The Film "The Purple Rose of Cairo"itsdonicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pirandello and The Waiting Stage of The Absurd (With Some Observations On A New "Critical Language")Dokument11 SeitenPirandello and The Waiting Stage of The Absurd (With Some Observations On A New "Critical Language")Cesar Octavio Moreno ZayasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Storytelling in Acousmatic Music - YoungDokument5 SeitenStorytelling in Acousmatic Music - Youngpanos amelides100% (1)

- Cinematic Analysis Quarter 2 FinalDokument6 SeitenCinematic Analysis Quarter 2 FinalAnonymous BRSBwT8Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 Pa129 Finalpaper PilaspilasDokument5 Seiten2019 Pa129 Finalpaper PilaspilasCristina PilaspilasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black Swan EssayDokument10 SeitenBlack Swan EssayNancy GuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ploning, Faith Depiction in Film: Jophen Baui Candidate, PHD LITDokument11 SeitenPloning, Faith Depiction in Film: Jophen Baui Candidate, PHD LITJosefina BauiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Age of Innocence AnalysisDokument4 SeitenThe Age of Innocence AnalysissimplyhueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deleuze and CinemaDokument237 SeitenDeleuze and CinemaElenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dignity EssayDokument7 SeitenDignity Essayfz5s2avw100% (2)

- CloudsOfSilsMariaDP LightDokument24 SeitenCloudsOfSilsMariaDP LightAnderson VitorinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trilogia de Satyajit RayDokument4 SeitenTrilogia de Satyajit RaynarazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plato's CaveDokument2 SeitenPlato's CaveSamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peter Schumann's Bread and Puppet TheaterDokument13 SeitenPeter Schumann's Bread and Puppet TheaterRéka DeákNoch keine Bewertungen

- Question 2 For ScribdDokument3 SeitenQuestion 2 For ScribdEvieTheodoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- MebuyanDokument3 SeitenMebuyanSean Michael TomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theatre Research Paper TopicsDokument8 SeitenTheatre Research Paper Topicsafnkedekzbezsb100% (1)

- Woman in Black Drama CourseworkDokument4 SeitenWoman in Black Drama Courseworktvanfdifg100% (2)

- The Best Movies of 2021Dokument14 SeitenThe Best Movies of 2021siesmannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carl Jung and EducationDokument5 SeitenCarl Jung and EducationKellyNoch keine Bewertungen

- BEGINNING - PresskitDokument14 SeitenBEGINNING - PresskitvideotapekgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orphan Black: Performance, Gender, BiopoliticsVon EverandOrphan Black: Performance, Gender, BiopoliticsBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- South Atlantic Modern Language AssociationDokument16 SeitenSouth Atlantic Modern Language AssociationLeon LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phrasal Verbs StoryDokument1 SeitePhrasal Verbs StoryMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Handbook of Rhetorical Devices MB VersionDokument27 SeitenA Handbook of Rhetorical Devices MB VersionMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Ulysses" and The Moral Right To Pleasure - The New YorkerDokument6 Seiten"Ulysses" and The Moral Right To Pleasure - The New YorkerMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behave ClassDokument5 SeitenBehave ClassMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biz Prof TitlesDokument2 SeitenBiz Prof TitlesSyed Asrar AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flipping Your ClassroomDokument44 SeitenFlipping Your ClassroomMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gender Studies 2-2003Dokument112 SeitenGender Studies 2-2003MarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lifeskills BlackoutDokument2 SeitenLifeskills BlackoutMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rayuela y UlisesDokument29 SeitenRayuela y UlisesMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Reassessment of James Joyces Female CharactersDokument104 SeitenA Reassessment of James Joyces Female CharactersMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life Skills Are You ExperiencedDokument2 SeitenLife Skills Are You ExperiencedMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medea From PschychoanalisisDokument12 SeitenMedea From PschychoanalisisMariela50% (2)

- IC3 Pre Int Phrase Banks PDFDokument8 SeitenIC3 Pre Int Phrase Banks PDFMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Portrait Epiphanies PDFDokument25 SeitenA Portrait Epiphanies PDFMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medea From PschychoanalisisDokument12 SeitenMedea From PschychoanalisisMariela50% (2)

- Erotic Daydreams in Woolf OrlandoDokument5 SeitenErotic Daydreams in Woolf OrlandoMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writer's Diaries Woolf Alcott MansfieldDokument12 SeitenWriter's Diaries Woolf Alcott MansfieldMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deleuze's Spider Proust's NarratorDokument9 SeitenDeleuze's Spider Proust's NarratorMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary Consciousenness As Reflected in Images of The VampireDokument18 SeitenContemporary Consciousenness As Reflected in Images of The VampireMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Romeo and Juliet PROLOGUEDokument1 SeiteRomeo and Juliet PROLOGUEMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Handbook of Rhetorical Devices MB VersionDokument27 SeitenA Handbook of Rhetorical Devices MB VersionMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medea and JasonDokument16 SeitenMedea and JasonMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Telephone Call: Dorothy ParkerDokument4 SeitenA Telephone Call: Dorothy ParkerTeodor IoanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Networking in Comp Pre-Int SBDokument2 SeitenNetworking in Comp Pre-Int SBMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jane Austen and ShakespeareDokument22 SeitenJane Austen and ShakespeareMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wutherin Heights Bodies DissolutionDokument23 SeitenWutherin Heights Bodies DissolutionMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Company 3.0 Pre Int Worksheet U1Dokument1 SeiteIn Company 3.0 Pre Int Worksheet U1MarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Business Intermediate ContentsDokument1 SeiteThe Business Intermediate ContentsMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Company RestaurantsDokument1 SeiteIn Company RestaurantsMarielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Self As Cognitive ConstructDokument12 SeitenThe Self As Cognitive ConstructLiza Mae P. Tercenio50% (2)

- The Ego Matter: About The Importance of Autonomy For Realizing Your True SelfDokument340 SeitenThe Ego Matter: About The Importance of Autonomy For Realizing Your True SelfDr. Peter Fritz Walter100% (10)

- Philosophies EDUCATIONDokument23 SeitenPhilosophies EDUCATIONNeenu Rajput100% (2)

- The Self in Western and Eastern ThoughtsDokument15 SeitenThe Self in Western and Eastern ThoughtsAtteya Mogote Abdullah86% (28)

- Epistemology of Sri AurobindoDokument19 SeitenEpistemology of Sri AurobindoRyan RodriguesNoch keine Bewertungen

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY (P304) - Exam 1 Study Guide 1) Module 1: The Social SelfDokument7 SeitenSOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY (P304) - Exam 1 Study Guide 1) Module 1: The Social SelfjayhirshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 6 B Therapeutic Relationship-1Dokument36 SeitenUnit 6 B Therapeutic Relationship-1Nayel ZeeshanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9781935830238Dokument17 Seiten9781935830238prasadmvk50% (6)

- Dokumen - Tips - mgt611 Business Labor Law Solved Final Term Papers For Final Term Exam Apiningcomfilesgresga1ckwiftxgqsjbcrds1c02016 10 20mgt611 PDFDokument31 SeitenDokumen - Tips - mgt611 Business Labor Law Solved Final Term Papers For Final Term Exam Apiningcomfilesgresga1ckwiftxgqsjbcrds1c02016 10 20mgt611 PDFMOHSIN AKHTARNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perdev Answer KeyDokument5 SeitenPerdev Answer KeyMartinelli Ladores Cabullos96% (45)

- Brubaker Cooper - Beyond IdentityDokument21 SeitenBrubaker Cooper - Beyond IdentityplazmendesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is America Bourgeois?Dokument15 SeitenIs America Bourgeois?Sancrucensis100% (1)

- Module 1Dokument5 SeitenModule 1Santhosh Y M100% (1)

- Madurai Institute of Social Sciences Objectives Type Questions and Answers Life SkillsDokument8 SeitenMadurai Institute of Social Sciences Objectives Type Questions and Answers Life Skillsnirav121Noch keine Bewertungen

- Group4 Ppt. Understanding The SelfDokument16 SeitenGroup4 Ppt. Understanding The SelfLee Jo John PatrickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ge 1 Understanding The SelfDokument3 SeitenGe 1 Understanding The SelfJohn carlo Delos santosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Material SelfDokument29 SeitenMaterial SelfLJ100% (2)

- Personal DevelopmentDokument21 SeitenPersonal Developmentjessica.padilla01Noch keine Bewertungen

- Adult Development and LeadershipDokument28 SeitenAdult Development and LeadershipUsama dawoudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Male Grooming ProductsDokument29 SeitenThesis Male Grooming ProductsMichaelAngeloBattungNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Patriotism To MeDokument1 SeiteWhat Is Patriotism To MeRakesh S IndiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Audience and Purpose: 2analytical Tools ("The Big 5")Dokument3 SeitenAudience and Purpose: 2analytical Tools ("The Big 5")faithNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Care of The Self To Care ForDokument26 SeitenFrom Care of The Self To Care ForyyssffNoch keine Bewertungen

- B Ed AssignmentDokument66 SeitenB Ed AssignmentrashiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leonard Orr 52CODESDokument22 SeitenLeonard Orr 52CODESsuruvuveenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Glasgow Theses Service Theses@gla - Ac.ukDokument117 SeitenGlasgow Theses Service Theses@gla - Ac.ukrnggathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 2Dokument4 SeitenModule 2Julius CabinganNoch keine Bewertungen

- GEC 1 Chapter 1Dokument24 SeitenGEC 1 Chapter 1Kacey AmorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motivation Language Identity and The L2 Self - (Chapter 1 Motivation Language Identities and The L2 Self A Theoretical... )Dokument8 SeitenMotivation Language Identity and The L2 Self - (Chapter 1 Motivation Language Identities and The L2 Self A Theoretical... )Sally NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Physical and Sexual SelfDokument11 SeitenPhysical and Sexual SelfJohn Paul Vincent HidalgoNoch keine Bewertungen