Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The United Nations Joint Logistics Centre (UNJLC) : The Genesis of A Humanitarian Relief Coordination Platform

Hochgeladen von

Fidel AthanasiosOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The United Nations Joint Logistics Centre (UNJLC) : The Genesis of A Humanitarian Relief Coordination Platform

Hochgeladen von

Fidel AthanasiosCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

603-010-1

The United Nations Joint Logistics Centre

(UNJLC):

The Genesis of a Humanitarian Relief

Coordination Platform

02/2008-5093

This case was written by Ramina Samii, Research Associate, and Luk N. Van Wassenhove, the Henry Ford Chaired

Professor of Manufacturing at INSEAD. It is intended to be used as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate

either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Fritz Institute.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

NB: TO ORDER COPIES OF INSEAD CASES, SEE DETAILS ON BACK COVER. COPIES MAY NOT BE MADE WITHOUT PERMISSION.

ecch the case for learning

Distributed by ecch, UK and USA

www.ecch.com

All rights reserved

Printed in UK and USA

North America

t +1 781 239 5884

f +1 781 239 5885

e ecchusa@ecch.com

Rest of the world

t +44 (0)1234 750903

f +44 (0)1234 751125

e ecch@ecch.com

603-010-1

Introduction

Between 4 February and 5 April 2000, Mozambique was hit by a quick succession of four

devastating cyclones. The worst floods in living memory swamped the southern part of the

country. Whilst tourists and businessmen stayed away from the area, Maputos hotels, bars

and restaurants were filled with foreign aid workers1 and journalists. Television cameras were

there to document both the devastation and the efforts of humanitarian organisations.2

As the footage of baby Rositas birth in a tree travelled around the world, humanitarian

organisations were confronted with a pressing problem: accessing the affected populations

without a supporting infrastructure network. With airstrips, roads and bridges under water,

rescuing the victims and delivering basic relief items such as food, shelter and medicine were

extremely difficult.

The logistical constraints imposed by the floods made airlifts the only viable means of

transportation. It was also the most expensive method. Given the huge demand for air assets,

there was a pressing need to enhance the efficiency (in terms of lives saved and immediate

assistance) and cost-effectiveness of the overall humanitarian relief effort. But which

humanitarian UN Agency or NGO was to coordinate the use of the available air assets? Who

was to decide on how to prioritise between transporting food, typically a low-value high-bulk

item, and non-food, high-value low-bulk items?

On the governments invitation, the OCHAs UNDAC3 team reached the disaster area on

12 February, a week after the first cyclone had hit Mozambique. The team assisted the

government in preparing a consolidated appeal to mobilise funds from the donor community.

Among other things, it set up the Cell for Logistics Coordination, hosted by the National

Institute for Disaster Management (Instituto Nacional de Gestao de Calamidades, INGC),4

with the mandate to coordinate assessment and relief activities. Was OCHA the most

adequate body to carry out the logistics coordination task? Or was an agency like the WFP,5

designated in 1999 as the lead coordinating agency for disaster management in Mozambique,

a better choice?

The 2000 Mozambique Floods

Cyclone Connie hit the southeast coast of Mozambique on 4 February 2000, severely

affecting three of the countrys provinces. The rapid rise in the water level resulted in

1

2

3

4

5

2,500 UN and NGO aid workers were mobilised for the disaster.

See Appendix A for a short description of all the actors on the humanitarian intervention scene appearing in

this case.

The UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Assistances (OCHA) Disaster Assessment Coordination

team (UNDAC), deployed for sudden onset of natural disaster, prepared consolidated appeals on behalf

of the concerned government and UN humanitarian organisations for donor funding.

At the time of the floods it had only initiated the contingency planning exercise.

The UNs World Food Programme (WFP) with the mission to fight against global hunger was the biggest

supply mover with the most developed logistics competencies within the humanitarian community.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

widespread flooding of the major river basins.6 The cyclone continued inland causing

substantial damage to four neighbouring southern African countries (Exhibit 1). The opening

of dams upstream (especially in Zimbabwe and Zambia) worsened the situation. The capitals

water and electricity supplies were the first to be severely affected. In a matter of hours, road

and rail links to the bordering countries of South Africa and Swaziland were cut, railway

services between Maputo and Zimbabwe were impeded, airfields were under water,7 property

and thousands of acres of land were destroyed, water purification plants, boreholes, wells

were damaged and 100,000 people were left homeless or stranded on islands of rooftops

and trees.

The severe floods were aggravated by a second cyclone, Eline that struck the eastern coast of

Mozambique on 21 February and moved inland producing heavy rains and strong winds for

three consecutive days. By the end of February, the worst and most extensive floods the

country had known for 150 years had affected over 900,000 people, forcing 300,000 people to

abandon their homes, washing away 1,600km of roads, and destroying cultivated land and

numerous bridges connecting the provinces.8 The threat of water-borne diseases such as

cholera and malaria increased daily from the pools of stagnant water and unsanitary

conditions.

By early March, intermittent rainfall continued to affect parts of the country. In addition, a

new cyclone, Gloria, was hovering in the Indian Ocean. Up until the end of March, the heavy

rains continued to inhibit the distribution of relief items by road, as repaired roads were

intermittently put out of use. The countrys main highway was opened to traffic on 26 March

providing better access to the flood affected areas. The first trucks with supplies from Beira to

the Gaza province were dispatched on 29 March. By the end of the month an estimated 1.2

million people had been affected by the floods. Of those, 463,000 internally displaced people

had received assistance from humanitarian organisations and were sheltered and fed in over

120 accommodation and feeding centres set up throughout the affected areas.

On 5 April the last and relatively confined cyclone, Hudah, hit the Mozambique coast with

limited displacement of people and loss of crops. By June, the official and revised figures of

the disaster indicated that 5 million people had been affected by the flooding, with 544,000 of

these being displaced (Exhibit 2).9 At the peak of operations out of Beira and Maputo, a total

of 57 aircraft of several types belonging to different operators were involved in humanitarian

relief activities. The combined humanitarian air operation of the disaster was among the

largest ever: a total of 9,305 flight hours, transporting almost 30,400 passengers and 11,623

metric tonnes (MT) of food and non-food items (Exhibit 3). These results were possible

thanks to the activation of the UNs Joint Logistics Operations Centre (JLOC), a coordination

mechanism first developed in the Eastern Zaire 1996-1997 crisis.

6

7

8

9

Nkomati, Limpopo, Save and Buzi river systems.

Over the four-day period (4-7 February), rainfall reached a record 454mm at Maputo International Airport

Source: Mozambique & Zimbabwe: Flood Rehabilitation, Appeal no. 4/2000, Situation Report no. 2,

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent, 23 February 2000.

Source: UN Coordination in Mozambique Following the Devastating Floods, June 2000.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

The Mozambique JLOC

At the time of the disaster, the government of Mozambique only had two helicopters at its

disposal, and one of these was grounded for repairs. Within days of the governments first

appeal for international assistance, the South African National Defence Force had provided a

fleet of 10 aircraft. On 11 February the first South African military rescue helicopters arrived

at the disaster site. Between 11 and 19 February, they choreographed the first wave of rescue

operations. As the situation stabilised, donors started to scale down their operations. The

OCHAs UNDAC mission left the country on 24 February after completing the first

consolidated appeal. When the second wave of floods hit Mozambique between 26 and

27 February, no single organisation was prepared for its abruptness and magnitude. On

29 February the UNDAC team returned to the country to prepare the second appeal.

Rescue operations resumed and reached their peak right after the second cyclone. Thousands

of people clinging to life in trees or on rooftops had to be rescued and given relief. It was the

helicopter crews hour of glory as rescue operations were often carried out at great personal

risk. The pilots and the crew were real heroes, working tirelessly and alone around the clock

to save lives. For a week on a daily basis, an average of more than 2,000 victims were literally

lifted from trees and rooftops, put on islands and kept alive with relief supplies provided by

a host of humanitarian agencies.

After the second cyclone hit, professional planning was required to obtain optimal utilisation

of the 50-plus aircraft provided by 15 operators10 to support the victims (Exhibit 4). As the

magnitude of the emergency was revealed and air activities evolved from straightforward

rescue to transporting food and non-food items including shelter, medicine and water, the

complexity of the logistics operations was compounded. On the initiative of a UNDAC team

member,11 the Minister of Foreign Affairs requested that the Cell for Logistics Coordination

be converted into a Joint Logistics Operations Center (JLOC) on 3 March 2000. This JLOC,

hosted in the INGC building, reported to the Mozambique government and as such became an

instrument of the governments rescue and relief operations. While DFID temporarily

appointed one of its officers to activate the JLOC, WFP, the mastermind behind the Joint

Logistics Centre (UNJLC)12 concept back in 1996, was designated as the lead coordinating

agency for logistics support and communications.

WFP designated Wilfried De Brouwer, an ex-pilot and periodic OCHA consultant, as head of

the centre. He recalled that, Without office equipment or communication lines, a locallyrecruited UNDP13 logistics fficer and I started work on 8 March. Sitting on the floor with my

laptop on my knees and with the support of WFPs head of air operations, I began planning

and coordinating airlift operations. After a few days, the US military provided the JLOC

with furniture, maps and office equipment. This, De Brouwer noted, gave the JLOC the

required legitimacy to direct air operations given its national status and very presence in the

10 Among which were government aircraft and helicopters from Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Malawi,

Portugal, South Africa, Spain and the US.

11 Seconded by DFID, the UK government Department for International Development.

12 Since the concept was developed in 1996, the Joint Logistics Centres, if named at all, have been referred to

differently each time they are formed (e.g. UNJLC, JLOC, etc.).

13 Within the UN system, the United Nations Development Programme is the principal provider of

development advice, advocacy and grant support.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

INGC building. In spite of repeated promises, the office lacked basic services such as

telephone landlines, fax and email connections throughout its two-month operation. This

prevented it from communicating effectively with civil aviation authorities and the

humanitarian agencies. JLOC relied on the WFP Mozambique office in Maputo for

administrative support and logistics systems. The latter provided it with mobile phones and

transportation.

The Centre was slowly manned. WFP assigned an experienced loadmaster to organise the

loading of the cargo. We were understaffed to accomplish our mission. I approached the

military forces and fortunately had four military staff (one UK and three US) seconded to the

JLOC, said De Brouwer.

At the onset of the emergency, there was little understanding of the concept and mandate of

the JLOC among the humanitarian community and military actors. The concept gained

credibility through the daily updates at the coordination meetings chaired by the Minister of

Foreign Affairs which were attended by humanitarian organisations and the media. These

meetings became a forum to reiterate that the JLOC was not a WFP satellite, but an impartial

set-up to support the humanitarian community with the commonly available logistics assets,

said De Brouwer. But we still failed to ensure the participation of other humanitarian

organisations through secondment of their experienced staff to the JLOC.

In this particular operation, the JLOC coordinated only regional airlifts (movement of goods

from the region into the disaster areas) and not strategic ones (movement of supplies from

other continents into eastern and southern Africa). To ensure the smooth influx and movement

of relief items, it dealt with a series of administrative issues. With the support of OCHA,

INGC and the Minister of Foreign Affairs, it sought and obtained facilitation measures from

the local authorities such as exemption from landing and navigation fees, immigration

procedures, customs clearance, etc.

The way the air operations were managed seemed to favour the most dynamic and betterorganised humanitarian agencies. Initially this created some misunderstandings among less

prepared, smaller organisations as typically the stronger were the ones that managed to

conform to the mission schedule by getting their items on the tarmac at the correct shipping

time (Box A). De Brouwer reiterated, Efficient air management leaves no room for

amateurism. Flight schedules have to be strictly adhered to. If not, multiple flying hours and

thousands of dollars are wasted.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

Box A

Air Management: Prioritisation, Tasking and Scheduling

The JLOC introduced a mission request form that had to be completed by humanitarian

organisations before 1.pm on the day before execution. The schedule was discussed with the

operators (mostly military) during a daily meeting at 4.pm when the requests were matched

with the available assets and tasks appointed to the respective operators and aircraft types.

Subsequently, humanitarian organisations were informed by mobile phone and the schedule

was finalised by 6.pm. This scheduling cycle allowed a maximum of flexibility and took into

account newly injected priorities and the backlog from the previous day. On the other hand,

users only received flight confirmation after the 4.pm meetings. To maximise the use of assets

avoiding waste and delays, organisations were informed that a request implied readiness to

execute the following day. In the event of late arrival at the airport, users would lose priority

and the JLOCs mission monitor had the prerogative to reassign the space to readily available

cargo at the airport.

In prioritising the cargo and destinations, the JLOC based itself on the overall humanitarian

need-driven guidelines emanating from the different coordination meetings held with INGC,

the UN Country Resident Representative, OCHA, and the UN Agencies.

On the operational side, things went very smoothly: without a hitch. The South African Air

Force had assumed the role of planning and assigning air missions before the activation of the

JLOC. De Brouwer recalled, We were quite lucky as upon its activation, the JLOC, apart

from few minor incidents at the airfield level, was accepted by the military as the body in

charge of prioritising, tasking, and scheduling air assets. Our task, although never formalised,

was to plan and schedule the use of air assets leaving the actual coordination of the execution

largely to the South African Air Force. The international military personnel14 agreed to be

coordinated by civilians and the JLOC to an unprecedented extent. The JLOC carefully

prepared compulsory daily briefings with all pilots. As a result, almost 10,000 hours, or the

equivalent of 15,000 to 20,000 flights were organised without accident (Exhibit 3).

Airlifts are essential to ensure quick response, but they are also the most expensive means of

transport hence calling for proper management, said De Brouwer. With the argument that

humanitarian support flights had priority, I was forced to systematically refuse and resist the

pressure to dedicate helicopters for VIP and other visitors use. On the other hand, to keep

the floods on the worlds television screens and support the fundraising efforts, the JLOC

coordinated and secured necessary seats for journalists. Looking back at the Mozambique

2000 floods, De Brouwer reflected, Up to then, there had been few emergencies that had

received as much media attention as the second flooding in the Limpopo Valley. The

international television teams already in the country were able to record and broadcast

dramatic pictures of the second cyclone and, as such, generated considerable donor support.

14 A total of more than 1,000 foreign military personnel operated in the country.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

In addition to air management, the JLOC had to perform a stock tracking function. This was a

difficult task given the poor reporting procedures. JLOC limited itself to the registration of

food items, which constituted 75-80% of all transported cargo. Without an effective authority

that could manage the movement control (receiving, storing and distribution) of unsolicited

food and non-food items provided by private and public donors, the JLOC undertook the task.

To augment the reach of the operations (rescue and relief distribution), a number of NGOs

and governments (the Netherlands and the UK) stepped up their support through generously

providing 230 boats. Although not designated as the coordinating body for the use of other

assets except air, the JLOC was asked, on an ad hoc basis, to trace the distribution and ensure

the correct utilisation of these boats coming into the country.

Although donors continued to fund air operations until mid May 2000, from April, with fewer

air assets available, helicopter operations were centralised at main pick-up points, now

accessible by road from Maputo, closer to the crisis areas. This resulted in better use of

resources and hence a better cargo-flying hour ratio, explained De Brouwer. To reduce costs,

small boats were put into use to ferry supplies. As road access improved, expensive airlifts

were replaced by trucking. By the second week of April, with improved weather conditions,

displaced people started to return to their homes leaving the accommodation centres. In early

May, road routes into affected areas started drying up ready for rehabilitation or another round

of repairs. As the emergency relief effort moved into a rehabilitation phase, road access

improved and funding for the JLOC dried up,15 the decision to close down the JLOC was

taken by the government (Exhibit 5).

The Genesis of the UNJLC Concept

Traditionally, the coordination of logistics issues among humanitarian organisations was

managed by general coordination structures. The need for an appropriate and distinct

mechanism for intensifying inter-agency logistics coordination in large-scale emergencies

appeared continually as of the 1990s. From the mid-1990s onwards, quasi-UNJLCs were

initiated in a range of emergency environments. By March 2001, the concept caught the

attention of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), a body composed of UN

humanitarian agencies, the Red Cross movement and nearly 250 humanitarian NGOs. In its

role of setting humanitarian policy, the IASC tasked WFP to take a lead role in further

developing the UNJLC concept.

The UNJLC concept originated in 1996 as a spontaneous response to an overwhelming

humanitarian crisis arising from the outbreak of civil war in Zaire, when over a million

Rwandan refugees suddenly returned to their places of origin or moved deeper into the

country. In early December 1996, the UN Multi-National Peacekeeping Force (UNMNF)

arrived in Entebbe, Uganda. As an extension of its lead role in air logistics in this crisis, WFP,

together with UNHCR16 and OCHA, established an informal set-up at Entebbe airport as a

15 Funding for the JLOC operation was mobilised by WFP via the OCHAs UN/Government of Mozambique

consolidated international appeal of 24 February.

16 The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees is mandated to lead and coordinate international

action to protect refugees and resolve refugee problems worldwide. The UNs Humanitarian Coordinator

made WFP the lead agency for logistics and UNHCR lead agency for Eastern Zaire as well as the

repatriation programme. Within logistics, WFP was entrusted with the coordination of all air and train

movements, while UNHCR coordinated all river traffic and trucking operations.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

liaison point on logistics matters between the operational UN Agencies and the UNMNF. To

facilitate operations, OCHA attached an expert on civil-military coordination to this body. As

the involvement of the UNMNF in the region proved shorter than expected,17 the ad hoc setup evolved into a coordination body dealing with a variety of humanitarian logistics planning

and operational issues in the Great Lakes region. Staffed with representatives of the main UN

Agencies and NGOs, it began to process information on and manage common logistics

resources and operations for the three main UN operational Agencies WFP, UNHCR and

UNICEF18 involved in the region.

David Kaatrud, the WFP Great Lakes Regional Logistics Officer19 in Kampala, Uganda, and

the mastermind behind the UNJLC concept, reconstructed the events: The massive

movement and outflow of people in just a few days called for the immediate repositioning and

re-routing of humanitarian goods. To maximise the likelihood of food reaching people on the

move, he looked at all possible routes and entry points into the region that could be used to

move high-volume food items. It was a tricky situation involving a large shifting mass of

humanity in a remote area with little overland access, recalled Kaatrud. A logistical

nightmare as there were few roads and we did not have the faintest idea where people were,

nor where they intended to head.

Given the lack of infrastructure, WFP decided that the quickest way to reach the needy was

through air deliveries to airfields near concentrations of the refugee populations. Within a

short period, Kaatrud and his team organised the arrival of a few large aircraft. We

immediately started flying food into the region, borrowing from our stocks available in the

area for other operations, he explained. Within five days WFP trucks were delivering food

flown in from stocks in neighbouring countries. At the same time, WFP engaged in the time

consuming alternative of transporting food items overland to remote areas using surface

transportation (rivers and roads). To ensure the delivery of relief supplies to the refugees

moving across Zaire, satellite UNJLC-type set-ups were established at key logistics nodes.

It was not long before we realised, said Kaatrud, that only WFP and UNHCR had the

necessary transport means to reach the refugees. The other UN Agencies such as UNICEF,

WHO20 and a number of NGOs (e.g. Oxfam,21 MSF,22 and World Vision23) were having

logistical problems. While other humanitarian organisations had to rely on the few, decrepit

and dangerous roads and compete for the few local truck drivers, WFP and UNHCR, with

their large and smaller aircraft, were moving cargo, refugees and their personnel around the

region. It was there and then that we came up with the idea to pool and offer our excess air

assets cargo and passenger capacity to each other, said Kaatrud. After obtaining donor

acceptance, WFP and UNHCR aircraft used their excess return air capacity to move,

respectively, refugees and food items in and out of the region.

17 The UNMNF left towards the end of December after the sudden return of the refugees to Rwanda.

18 The United Nations Childrens Fund is dedicated to protecting children and their rights.

19 Kaatrud was promoted to Chief of Logistics, WFP, in 2000 and became Head of the UNJLC in 2001.

20 The World Health Organizations mission is the attainment of the highest possible level of health for all

people.

21 The Oxford Committee for Famine Relief aims to finding solutions to poverty and suffering worldwide.

22 Mdecins Sans Frontires is an independent humanitarian medical aid agency.

23 World Vision is a relief and development organisation.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

By mid-April 1997, WFP and UNHCR had reached an agreement. As the repatriation of

refugees from Kisangani to Goma (Zaire) and later on to Rwanda took priority, we agreed to

offer our air capacity to UNHCR by carrying refugees on our chartered aircraft (cargo in refugee out arrangement), said Kaatrud. As a result, during a seven-week period over 40,000

refugees were repatriated from Kisangani to Rwanda. Later on, when the requirements for

cargo shipments to Kisangani increased, UNHCR aircraft (brought on line for refugee

transportation) were used to transport WFP cargo. In addition to coordinating air asset use and

planning flight operations with the UNHCRs Movement Control units (MOVCON)

established at key nodes to process returnees, the UNJLC coordinated movement at the rail

link from Kisangani to the refugee concentrations to the south. This latter task included

delivering items to these camps and transfering returnees to the Kisangani airport.

Asset sharing went beyond WFP and UNHCR. In order to survive, the refugees needed food

(provided by WFP), medicine and medical care (e.g., to contain the outbreak of epidemics),

shelter, kitchen kits, clothing, etc. These were items typically furnished by other humanitarian

organisations. Given the mismatch between capacity and cargo, intensified coordination was

necessary so that logistics assets could be pooled and transportation of different food and nonfood items be prioritised.

The term UNJLC was coined at the outset of this crisis, explained Kaatrud. The joint

referred to the pooling of air assets and the centre referred to the single location for this

effort at Entebbe. The term, never revised, continued to be used throughout the Eastern Zaire

crisis even when the operation became geographically dispersed, as well as in future

operations with similar characteristics.

At the end of the crisis, the UNJLC operation was subject to a formal and joint evaluation by

UNHCR, UNICEF and WFP. The most important recommendation that emanated from this

exercise was the need for the humanitarian community to look further into the development of

the concept, reported Kaatrud. Consequently, the OCHA made a first attempt to formalise

the UNJLC concept by organising an inter-agency meeting of the agency heads of logistics to

discuss the UNJLC mechanism. Viewed as a neutral facility that served all humanitarian

agencies equally and indiscriminately, the objective of the UNJLC concept at that point in

time was to be a focal point for the importing, receipt, dispatch and tracking of both food and

non-food commodities during an emergency that foresaw multi-sectorial participation.

In 1998, WFP, UNICEF and UNHCR, through the WFP Nairobi regional office, pooled

resources and coordinated their air and surface response to the Somalia floods, a small-scale

emergency on the Kenya-Somalia border.

In the spring of 1999, the Balkan crisis broke out, causing mass movement of refugees from

Kosovo to Albania and Macedonia. The scale of this crisis took the international community

by surprise, but very soon a massive relief effort was underway with a large number of

humanitarian actors flooding the region with supplies in an often uncoordinated manner,

recalled Kaatrud. To address the crisis, WFP and UNHCR established separate massive

operations in each country. In Albania, the government put an operational coordination

structure between government and humanitarian agencies into place. In Macedonia, half a

million ethnic Albanian refugees entered the country from Kosovo in a very short period of

time. The humanitarian effort in Macedonia dealt with a straightforward logistics operation:

one single route that went through Skopje, Macedonia, to the refugee camps. To deal with

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

the refugee influx, the experienced WFP and UNHCR officers decided there and then to

activate a UNJLC in Skopje, said Kaatrud. The agencies used the UNJLC set-up to meet

and plan movements. However, the initiative suffered from insufficient allocation of staff

time by the participating agencies in the coordination effort. The effort was abandoned with

the return of the refugees to Kosovo. Throughout the crisis, a WFP staff seconded to a cell

installed in the UNHCR premises in Geneva, coordinated strategic air assets with NATO24

forces that controlled the regions airspace.

The WFPs air operation and logistics performance during the Balkan crisis had caught the

attention of the donor community. When the East Timor crisis erupted at the end of 1999,

there was interest to leverage these capabilities, not only to respond to the food aspect of the

crisis, but also to the needs of other agencies and NGOs. The WFP prepared a proposal

well funded by the donors for the provision of a wide-ranging, comprehensive common

logistics service that included passenger and cargo air services and sea movements from

Darwin, Australia, as well as in-country air, trucking, coastal shipping and warehouse

operations. Although this initiative was not called a UNJLC, a UNJLC-like facility was

established, said Kaatrud. Once this infrastructure and its assets were built up, there was a

need to prioritise, task and schedule the humanitarian traffic. To review plans and cargo

movements, WFP organised weekly meetings for the logistics operators of the different

agencies. To guide the operations and provide feedback to logistics planning, WFP antennas

at key logistics nodes collected and provided relevant information to humanitarian actors.

We provided these services to some 40 humanitarian organisations for a three-month

period, said Kaatrud. Although it was a small operation in terms of tonnage and population

assisted, it was a particular one as the transport infrastructure of the island was completely

burnt or removed.

On the request of the government, the UNJLC concept was successfully deployed again

during the 2001 Mozambique floods. Similar to the 2000 floods, the UNJLC dealt with air

asset management and logistics coordination. As mentioned above, after this emergency the

IASC requested that WFP formalise the UNJLC concept: a key point in its institutionalisation

process.

While the humanitarian community in Mozambique praised the UNJLC operations, the next

UNJLC deployment during the Bhuj earthquake in India was relatively less successful. De

Brouwer, who lead the effort, summarised, Initially WFP management was convinced that

the Indian army was capable of managing the response including any logistics coordination

issues. As a result, the decision to deploy the UNJLC concept was taken only after the arrival

of a WFP Emergency Response Team on the ground. In addition, the UNJLC was activated

without sufficient inter-agency and governmental consultation. Few people among the UN

Agencies, NGOs or local authorities were aware of the UNJLC concept. We arrived at the

disaster site two weeks after the earthquake of 26 January 2001 without knowing what type of

assistance was required, recapped De Brouwer. Moreover, upon arrival we had no office,

communications or information management facilities and were severely limited in terms of

the services we could provide. In the meantime the IFRC25 had set up a coordination

structure and had established a relationship with different authorities. In this disaster the

Indian government was particularly keen to manage the rescue and relief operations itself.

24 North Atlantic Treaty Organization is involved in peacekeeping and crisis management tasks.

25 The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent improves the lives of vulnerable people.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

This is a common scenario for natural disasters, confirmed Kaatrud. Sovereign

governments are there to manage their own disasters. The Indian government actually

outsourced logistics to a capable national NGO and as a result viewed the UN involvement in

logistics as redundant. As the UNJLC was deployed too late to meet its objective, it left the

disaster scene less than four weeks after its arrival with two major lessons learnt: timely

activation process and sufficient means once activated were crucial.26

In the summer of 2001, a UNJLC-type mechanism was activated by WFP during the crisis in

the Democratic Republic of Congo. In this crisis, WFP managed an inter-agency passenger air

service partially funded by OCHA. As a UN-mandated peace-keeping operation was active in

the country, the UNJLC component of the WFP operation consisted of the coordination of air

operations with this peacekeeping force.

Event of September 11th

Since the endorsement of the concept by the IASC in early 2001, WFP had taken the lead in

revising the concept in light of the inter-agency logistics coordination experiences of the last

years. As part of the concept development process, in early September 2001, it organised a

workshop in Brindisi, Italy, where an agreement was reached on the first draft of the UNJLC

Field Operations Manual. At the time of the workshop, just a week before the September 11

attacks in New York and Washington, we had a draft field operations manual for UNJLC

activation and deployment. But it still needed to be refined and backed-up by inter-agency

agreements, systems and training, summarised Kaatrud.

Without any advance notice and preparation, the decision to deploy the UNJLC, yet to be

formally institutionalised,27 was taken a fortnight after the events of September 11. We had

scheduled a number of activities but all our plans went belly up, said Kaatrud. The UNJLC

was to be mounted again, and quickly, in the most complex emergency scenario ever:

Afghanistan. Short of time, I began preparations to lead the effort.

26 For the convenience of the reader, Exhibit 6 summarises events marking the genesis of the UNJLC concept.

27 It was only after the deployment of the concept in diverse environments and conditions (e.g. sudden onset

of natural or man-made disaster, peacekeeping operations and complex emergencies involving refugees,

internally displaced persons, military action) that the UNJLC concept was institutionalised by the IASC in

March 2002 as an Inter-Agency humanitarian response facility under the custodianship of WFP.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

10

02/2008-5093

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

11

Exhibit 1

Mozambique 2000 Floods

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

603-010-1

Exhibit 2

Evolution of Estimates of Population Affected and Displaced

Date

12 February

21 February

End March

June

Population affected

200,000

900,000

1,200,000

5,000,000

Internally Displaced People

100,000

300,000

463,000

544,000

Source: UN Coordination in Mozambique Following the Devastating Floods, June 2000.

Exhibit 3

Mozambique JLOC Air Operations per Airfield and Executing Body

Air

Field

Hours

Cargo

Passengers

Transported

Victims

Rescued

Total

11408

2370

13778

6359

3443

3976

Passengers

Transported

14678

1873

16551

16343

208

0

Victims

Rescued

(Metric

Tons)

Maputo

Beira

Total

Military

NGO

Commercial

Execut

ion

7218

2087

9305

5398

2042

1865

Hours

9393

2229

11623

6399

1321

3903

Cargo

(Metric Tons)

30329

Source: WFP, Mozambique Floods February-May 2000, JLOC Report, 13 July 2000.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

12

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

3000

300

2500

250

2000

200

1500

150

1000

100

500

50

Air Assets Units (AAUs) Coordinated by JLC

Cargo transported (MT)

05.11.00

05.01.00

04.21.00

04.11.00

04.01.00

03.22.00

03.12.00

03.02.00

0

02.21.00

Number of People

350

02.11.00

Metric Tonnes (MT) and

AAUs

Exhibit 4

JLOC Mozambique Air Operations

No of Victims Rescued

Source: WFP, Mozambique Floods February-May 2000, JLOC Report, 13 July 2000.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

13

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

Exhibit 5

Mozambique Floods 2000 Chronology

1999

June

Event

WFP designated as lead agency in Mozambique for disaster management

November

2000

February 4-7

INGC Contingency Plan for 1999/2000 rainy season launched

February 7

Cyclone Connie hits Central and Southern Mozambique and then moves on

to drop record rainfall over Swaziland, South Africa, Zimbabwe and

Botswana

Roads from Maputo to South Africa and Swaziland cut

February 11

Arrival of first South African aircraft

February 1119

February 12

First wave of airlift rescue operations

February 17

First daily INGC/UNDAC briefing and coordination meeting, open to all

February 21

Cyclone Eline hits central Mozambique before moving inland over

Zimbabwe and northern South Africa

Launch of an international appeal by the Government of Mozambique in

collaboration with the United Nations (dated February 24)

UNDAC team leaves Mozambique

February 23

February 24

UNDAC team of five arrives in Maputo

February 2627

February 29

Second wave of floods hits Mozambique

March 3

Joint Logistics Operations Centre (JLOC) opens within INGC to coordinate

air assets

Mozambiques Foreign Minister chairs the daily briefings in INGC

March 6

March 8

March 26

March 29

April 5

April

May 5

Second UNDAC team arrives in Maputo

UNJLC becomes operational

The countrys main highway opens to traffic providing better access to the

flood affected areas

The first trucks with supplies from Beira to the Gaza province are dispatched

Hurricane Hudah hits Mozambique

Displaced people start returning to their homes

Closure of JLOC

Source: UN Coordination in Mozambique Following the Devastating Floods, June 2000.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

14

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

Exhibit 6

Timeline of the Genesis of the UNJLC Concept

Date

1996-1997

1997

1998

Spring 1999

End 1999

March 2000

January 2001

February 2001

March 2001

Summer 2001

September 2001

March 2002

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

Event

East Zaire Crisis

OCHA organises an inter-agency meeting of the agency Heads

of Logistics to discuss the UNJLC concept

Somalia Floods

Balkan Crisis

East Timor Crisis

Mozambique Floods

Mozambique Floods

Bhuj Earthquake

Endorsement of the concept by the IASC, with a request to

WFP to further develop the UNJLC concept

Democratic Republic of Congo Crisis

Afghanistan Crisis

Institutionalisation of the UNJLC concept by IASC

15

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

Appendix A

List of Actors

DFID

IASC

IFRC

INGC

MSF

NATO

OCHA

Oxfam

UNDAC

UNDP

UNHCR

UNICEF

UNMNF

WFP

WHO

World

Vision

Department for International Development is the UK government department responsible for

promoting development and the reduction of poverty.

Inter-Agency Standing Committee is composed of UN humanitarian agencies and

representatives of 200-250 humanitarian NGOs.

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescents mission is to improve the lives of

vulnerable people by mobilising the power of humanity. It focuses on four core areas:

promoting humanitarian values, disaster response, disaster preparedness, and health and

community care.

National Institute for Disaster Management of Mozambique. Set up in 1999, this oversight

institution attached to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation, Mozambique, has the

mandate to manage, develop mitigation policy, prepare for and coordinate disasters.

Mdecins Sans Frontires is an independent humanitarian medical aid agency committed to

two objectives: providing medical aid wherever needed and raising awareness of the plight of

people assisted.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization signed in 1949 created an alliance of 12 countries

committed to each others defence. By 1999 it had 19 member countries. Together with nonmember countries and other international organisations it is involved in peacekeeping and

crisis management tasks.

United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance mobilises and

coordinates the efforts of the international community to meet the needs of those exposed to

human suffering in disasters and emergencies.

Oxford Committee for Famine Relief is a development, relief, and campaigning organisation

dedicated to finding lasting solutions to poverty and suffering around the world.

The UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Assistances (OCHA) Disaster Assessment

Coordination team (UNDAC) is a rapid response tool (members arrive quickly and stay no

longer than two weeks) deployed for sudden onset of natural disaster. Its mandate consists

of the preparation of a consolidated appeal for the emergency on behalf of the government

and UN humanitarian organisations (Inter-Agency) for donor funding.

United Nations Development Programme is the UN's principal provider of development

advice, advocacy and grant support. It has six priority practice areas: Democratic governance,

poverty reduction, crisis prevention and recovery, energy and environment, IT and

communications, and HIV/AIDS.

Established in 1950, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees is dedicated to lead

and coordinate international action to safeguard the rights and well being of refugees and

resolve refugee problems worldwide.

Established in 1946, the United Nations Children Fund advocates for the protection of

childrens' rights, helps them meet their basic needs and expands their opportunities to reach

their full potential.

UN mandated Multi-National Peacekeeping (Military) Force deployed for the Eastern Zaire

emergency.

Set up in 1963, the World Food Programme is the United Nations frontline agency in the

fight against global hunger. In 2002 it had emergency and development projects in 82

countries worldwide.

Established in 1948, the World Health Organisation is the UN Agency dedicated to attaining

the highest levels of health (complete physical, mental and social well being) for all people.

A Christian relief and development organisation working for the well being of all people,

especially children.

Copyright 2003 INSEAD

16

02/2008-5093

603-010-1

To order INSEAD case studies please contact one of the three distributors below:

ecch, UK and USA

ecch UK Registered Office:

www.ecch.com

Tel: +44 (0)1234 750903

Fax: +44 (0)1234 751125

E-mail: ecch@ecch.com

ecch USA Registered Office:

www.ecch.com

Tel: +1 781 239 5884

Fax: +1 781 239 5885

E-mail: ecchusa@ecch.com

Boulevard de Constance, 77305 Fontainebleau Cedex, France.

Tel: 33 (0)1 60 72 40 00 Fax: 33 (0)1 60 74 55 00/01 www.insead.edu

Printed by INSEAD

Centrale de Cas et de Mdias Pdagogiques

www.ccmp-publishing.com

Tel: 33 (0) 1.49.23.57.25

Fax: 33 (0) 1.49.23.57.41

E-mail: ccmp@ccip.fr

1 Ayer Rajah Avenue, Singapore 138676

Tel: 65 6799 5388 Fax: 65 6799 5399

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shakespearean InsultsDokument2 SeitenShakespearean InsultsFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Επιχειρήσεις Μαζικής ΕστίασηςDokument12 SeitenΕπιχειρήσεις Μαζικής ΕστίασηςFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- (Of War & Peace. About Weapons and ArmourDokument3 Seiten(Of War & Peace. About Weapons and ArmourFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Internal Control Practices in Casino GamingDokument17 SeitenInternal Control Practices in Casino GamingFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Air France 447 DisasterDokument16 SeitenAir France 447 DisasterFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Air France 447 DisasterDokument16 SeitenAir France 447 DisasterFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Turkey Vision 2023Dokument32 SeitenTurkey Vision 2023Fidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- History of The Special Air ServiceDokument15 SeitenHistory of The Special Air ServiceFidel Athanasios100% (1)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Τaylor-Elias Petropoulos, A PresentationDokument33 SeitenΤaylor-Elias Petropoulos, A PresentationtasospapacostasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Views of The Joint Chiefs of Staff PDFDokument4 SeitenViews of The Joint Chiefs of Staff PDFFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Special Air ServiceDokument10 SeitenSpecial Air ServiceFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Acheson Speech On The Far East - 12 January 1950 PDFDokument3 SeitenAcheson Speech On The Far East - 12 January 1950 PDFFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Τaylor-Elias Petropoulos, A PresentationDokument33 SeitenΤaylor-Elias Petropoulos, A PresentationtasospapacostasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- South African Border WarDokument7 SeitenSouth African Border WarFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Wiki - Rhodesian Special Air ServiceDokument4 SeitenWiki - Rhodesian Special Air ServiceFidel Athanasios100% (1)

- Quick Sketch of The Zimbabwe, Rhodesia Bush WarDokument8 SeitenQuick Sketch of The Zimbabwe, Rhodesia Bush WarFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Μount DarwinDokument3 SeitenΜount DarwinFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Physical Fitness CertificateDokument6 SeitenThe Physical Fitness Certificateniraj_sdNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Biological Warfare in RhodesiaDokument3 SeitenBiological Warfare in RhodesiaFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Korean War Educator - Machines of War - CommunicationsDokument9 SeitenKorean War Educator - Machines of War - CommunicationsFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ifla 2010-2015 PDFDokument6 SeitenIfla 2010-2015 PDFFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Νεοκαθαρεύσα και εξαγγλισμός της Ελληνικής - ΠετρούνιαςDokument13 SeitenΝεοκαθαρεύσα και εξαγγλισμός της Ελληνικής - ΠετρούνιαςFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- SOE in GreeceDokument43 SeitenSOE in GreeceFidel Athanasios100% (1)

- Signal Corps During The Korean War IIDokument13 SeitenSignal Corps During The Korean War IIFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Signal Corps During The Korean War IDokument7 SeitenSignal Corps During The Korean War IFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Overview of The Korean WarDokument8 SeitenAn Overview of The Korean WarFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consice History of The Greek Expeditionary Force (GEF) in Korea (1950-1955)Dokument5 SeitenConsice History of The Greek Expeditionary Force (GEF) in Korea (1950-1955)Fidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Signal Corps During The Vietnam WarDokument17 SeitenSignal Corps During The Vietnam WarFidel Athanasios100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Signal Corps During The Korean War IIDokument13 SeitenSignal Corps During The Korean War IIFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Νεοκαθαρεύσα και εξαγγλισμός της Ελληνικής - ΠετρούνιαςDokument13 SeitenΝεοκαθαρεύσα και εξαγγλισμός της Ελληνικής - ΠετρούνιαςFidel AthanasiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21M LGM30G 2 28 1Dokument476 Seiten21M LGM30G 2 28 1nasrpooyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Camelbak Mil Spec AntidoteDokument2 SeitenCamelbak Mil Spec AntidotesolsysNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cheat Code Vice CityDokument76 SeitenCheat Code Vice CityKuldeep GohelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Terfenol D DatasheetDokument2 SeitenTerfenol D DatasheetFirstAid2Noch keine Bewertungen

- GumbaDokument3 SeitenGumbasantosh pandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malcolm Gladwell - How David Beats GoliathDokument15 SeitenMalcolm Gladwell - How David Beats GoliathIgor Chalhub50% (2)

- Radukar The Beast: WarscrollDokument1 SeiteRadukar The Beast: WarscrollParvus AresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aroo's Gun RecommendationsDokument25 SeitenAroo's Gun RecommendationsAngry CrackerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iran and Its Neighbors: Regional Implications For U.S. Policy of A Nuclear AgreementDokument60 SeitenIran and Its Neighbors: Regional Implications For U.S. Policy of A Nuclear AgreementThe Iran Project100% (3)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- ReadmeDokument12 SeitenReadmeIdan GeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recount TextDokument16 SeitenRecount TextAnnisaazhrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 8. Middle English. Scandinavian and Norman Conquests.Dokument3 SeitenLecture 8. Middle English. Scandinavian and Norman Conquests.aniNoch keine Bewertungen

- WMV130C1 - BTR-90 Archived AUGDokument6 SeitenWMV130C1 - BTR-90 Archived AUGsniper coldeyeNoch keine Bewertungen

- KettlebellDokument89 SeitenKettlebellluis_tomazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jawa CatalogueDokument45 SeitenJawa CatalogueSRV MOTORSSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lista de PersonalDokument21 SeitenLista de PersonalLidda Livia Soto LeonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abu GhraibDokument21 SeitenAbu GhraibAnshuman Tagore100% (1)

- 2 NL Tamil 2023 Model Paper 02Dokument11 Seiten2 NL Tamil 2023 Model Paper 02denethk08Noch keine Bewertungen

- Thunaipadam (X-CW)Dokument4 SeitenThunaipadam (X-CW)kamali kamaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antoni Macierewicz Report On Liquidation of The Polish Military Information ServicesDokument147 SeitenAntoni Macierewicz Report On Liquidation of The Polish Military Information ServiceskabudNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Infantryman's Guide To Combat in Built-Up AreasDokument350 SeitenAn Infantryman's Guide To Combat in Built-Up Areasone2much100% (3)

- Diario of Christopher ColumbusDokument2 SeitenDiario of Christopher ColumbusEric Burt100% (1)

- Cryptography: Name Pratik DebnathDokument12 SeitenCryptography: Name Pratik DebnathSubir Maity100% (3)

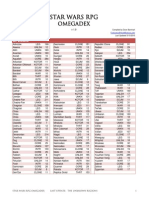

- Star Wars RPG: OmegadexDokument57 SeitenStar Wars RPG: OmegadexMauro VelezNoch keine Bewertungen

- AP History NotesDokument153 SeitenAP History NotesvirjogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Genesis For The New Space AgeDokument240 SeitenGenesis For The New Space Agelodep96% (23)

- Building An Elite For Indonesia (1951-1967)Dokument17 SeitenBuilding An Elite For Indonesia (1951-1967)apri.kartiwanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The British Way With Umbrellas PDFDokument1 SeiteThe British Way With Umbrellas PDFAndrewChesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peñaranda Nueva EcijaDokument5 SeitenPeñaranda Nueva EcijaLisa MarshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Awaiting The Allies' Return (Villanueva Dissertation) (FINAL DRAFT) (04 FEB 2019)Dokument276 SeitenAwaiting The Allies' Return (Villanueva Dissertation) (FINAL DRAFT) (04 FEB 2019)Jessa CordeNoch keine Bewertungen

- How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyVon EverandHow States Think: The Rationality of Foreign PolicyBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (7)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentVon EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (7)

- Son of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesVon EverandSon of Hamas: A Gripping Account of Terror, Betrayal, Political Intrigue, and Unthinkable ChoicesBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (499)

- Stalin's Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana AlliluyevaVon EverandStalin's Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana AlliluyevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldVon EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (1145)

- The Only Thing Worth Dying For: How Eleven Green Berets Fought for a New AfghanistanVon EverandThe Only Thing Worth Dying For: How Eleven Green Berets Fought for a New AfghanistanBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (25)

- The Mysterious Case of Rudolf Diesel: Genius, Power, and Deception on the Eve of World War IVon EverandThe Mysterious Case of Rudolf Diesel: Genius, Power, and Deception on the Eve of World War IBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (81)