Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Literary and Visual Narratives in Gandha PDF

Hochgeladen von

Linda LeOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Literary and Visual Narratives in Gandha PDF

Hochgeladen von

Linda LeCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

13 Literary and Visual Narratives in

Gandhran Buddhist Manuscripts

and Material Cultures

Localization of Jtakas, Avadnas,

andPrevious-Birth Stories

Jason Neelis

LOCALIZATION OF BUDDHISM IN GANDHRA

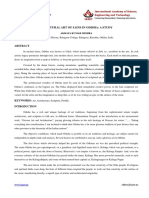

Around the beginning of the Common Era, local patrons and powerful regional

rulers fuelled the production of early Buddhist literary and material cultures in

ancient Gandhra. Their support contributed to the growth of Buddhist stpas

and residential monasteries in the Peshawar basin and neighboring regions of the

Swat and Kabul valleys of northwestern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan (Figure13.1).

Artisans belonging to regional ateliers synthesized and transformed local,

Indian, Iranian, Central Asian, and Hellenistic visual elements and styles in Buddhist sculptures and architecture at Gandhran archaeological complexes. While

distinctively hybrid features in Gandhran Buddhist art continue to attract interest,

recent acquisitions of collections of very early Buddhist manuscripts from the first

century bce to third century ce supply valuable written evidence for the emergence and development of Gandhran Buddhist literary traditions in the regional

vernacular language of Gndhr. Material culture and newly emerging literary

sources reflect Gandhran Buddhist efforts to establish and consolidate a Buddhist

presence and to domesticate narratives in order to make Gandhra a second holy

land (Foucher 19051951: 2.417) through institutionalization of what Jonathan

Z. Smith (2004: 10116) might a call a Buddhist topography of the sacred with

its own power of place (Huber 1999; Robson 2009).1

This contribution addresses methodological implications of differences

between Gandhran versions of literary and visual narratives of the Buddhas

previous births. The historical Buddha (kyamuni) did not visit Gandhra in

person during his own lifetime, aside from a miraculous journey with Vajrapi

described in an apocryphal account of his northwestern dharma conquest in the

Mlasarvstivda Vinaya (Przyluski 1914). However, Buddhist narratives link

events during his previous births to specific stpas, shrines, and pilgrimage sites

in Gandhra and neighboring regions or cities, such as the ancient metropolis of

Taxila and the Swat valley. Buddhist rebirth narratives depicted in Gandhran

sculptures and preserved in Gndhr manuscripts demonstrate a rich interplay

between literary and material cultures in specific regional and cultural contexts

6244-264.indb 252

1/16/2014 8:20:05 PM

Narratives in Buddhist Manuscripts 253

Figure 13.1 Gandhran Buddhist archaeological and pilgrimage sites. Designed by Jason

Neelis and Andrea Philips.

during the early centuries ce, and differences between the types of stories selected

for transmission in written and visual media raise several questions:

1. How does Buddhist literature in Gndhr relate to the material culture of

Gandhran Buddhist art, archaeology, and pilgrimage patterns?

2. Why were certain narratives and motifs selected for written transmission

and visual representation?

3. How are tensions between fidelity to narrative details, structure, and content and flexible innovation, which facilitated reception and adaptation in

the Gandhran cultural milieu, resolved?

A comparative focus on Jtakas in Gandhran sculptures and narrative summaries of Avadnas and Prvayogas in Gndhr manuscripts reveals uneven

patterns of transmission of written and visual narratives and varying degrees of

hybridity and originality. Gndhr Avadnas and Prvayogas overlap with widespread Jtaka narratives of the Buddhas earlier lives in Pli, Sanskrit, Chinese,

Tibetan, and Southeast Asian vernacular literature (Skilling 2008). Depictions of

rebirth narratives in Buddhist art, including Jtakas labelled with second-century

bce Brhm inscriptions at Bhrhut (Lders 1963), and found at other Indian sites

including Aja (Schlingloff 2000), Bodh Gaya, Sc, Amarvat, Mathur,

and Kanganhalli (Meister 2010) reflect complex interplay between oral, written,

and visual repertoires. These illustrations presuppose the emergence of rebirth

6244-264.indb 253

1/16/2014 8:20:05 PM

254 Jason Neelis

narratives in oral storytelling traditions, which were not necessarily replicated in

Pli and Sanskrit texts (Santoro 1999; Schlingloff 1982; Taddei 1999). Original

narrative compositions labelled as Avadnas and Prvayogas in Gndhr Buddhist

manuscripts briefly summarize the previous births and notable exploits of various

figures, from kyamunis followers to contemporary Gandhran figures from the

first century ce. Gndhr versions with formulae calling for the informal summaries to be expanded in greater detail belong to the initial stages of a transition

from oral to written transmission and provide the earliest literary evidence for the

development of important narrative genres. The extent of fidelity to South Asian

models and innovative appropriation of non-Indic elements, motifs, and characters

varies according to media, genre, chronology, and subregional factors. Anomalies of material and literary production of Jtaka episodes depicted in Gandhran

art and Avadna and Prvayoga narratives summarized in original compositions

in Gndhr manuscripts apparently reflect separate patterns of trans-localization,

reconfiguration, and re-contextualization of Buddhist narrative imagery and texts.

In contrast to studies of early Buddhist traditions based mainly or even exclusively on literary texts, material sources initially provided immediate access to

Gandhran Buddhist practices and visual culture, while an emerging corpus of

Gandhran Buddhist texts has become greatly enlarged by discoveries within the

last two decades.2 The sources now available shed light on distinctive features of

Gandhran Buddhism, which was in dynamic flux since the first stages of implantation (Fussman 1994), probably during the time of the Mauryan emperor Aoka

(ruling ca. bce 272232), whose Kharoh, Greek, and Aramaic inscriptions signaled administrative control of the northwest.3 Archaeological explorations and

excavations since the nineteenth century testify to high levels of cultural production in Gandhra, where economic surpluses generated by agriculture and trade

contributed to urban growth and generated material support for a proliferation of

Buddhist stpas and monasteries clustered outside of settlements and on hillsides

and transit routes in the early centuries ce. Sculptures and other artifacts from

Buddhist sites are especially rich sources for well-developed art-historical analyses of religious iconography and intercultural exchanges pioneered by Alfred

Foucher, the father of Gandhran studies (Zwalf 1996: 74) who established the

French Archaeological Mission in Afghanistan in 1922 and promoted a theory of

a Graeco-Buddhist school of art with Gandhra serving as a transit zone for the

diffusion of foreign influences from Europe to Asia.4 Numismatic evidence from

coins and seals serve as crucial pieces to the puzzle for reconstructing a relative

chronological framework for regional political history and illustrate the use of

intercultural and inter-religious symbolism.5 In addition to Aokan inscriptions,

around 800 Gndhr inscriptions record donations of various gifts to Buddhist

communities in Gandhra, thereby testifying to practices of veneration and

patronage, the distribution of monastic orders, and movement along routes for

commercial and religious exchange.6 Since the British Librarys acquisition of

Kharoh fragments in 1994, additional collections of early Buddhist manuscripts

written in the Kharoh script and Gndhr language have significantly expanded

the available corpus of textual materials for Gandhran Buddhist literary culture

6244-264.indb 254

1/16/2014 8:20:05 PM

Narratives in Buddhist Manuscripts 255

beyond a single incomplete manuscript of a Gndhr version of the Dharmapada

discovered far outside of Gandhra in Khotan in 1892.7 Cross-cultural contact

and inter-religious exchange were significant catalysts for religious mobility and

institutional expansion beyond Gandhra to Bactria and the Tarim Basin.

TRANSMISSION OF REBIRTH NARRATIVES IN

GNDHR MANUSCRIPTS

An expanded corpus of Gandhran Buddhist manuscripts calls for provisional

assessments of relationships with the material culture of Gandhran Buddhist

art and archaeology. While selective appropriation of hybrid features is readily

apparent in Gandhran visual imagery, the extent to which Gandhran Buddhist

literary texts are culturally distant or relatively close to Indian Buddhist literary

traditions varies significantly. Depending on the genre and style, Gndhr manuscripts exhibit various levels of originality, innovation or fidelity to Indian Buddhist

parallels. In a survey of recently discovered Buddhist Manuscripts from Afghanistan and Pakistan, Mark Allon (2008: 162) observes that Gandhran Buddhists

transmitted stras and other texts from the Indian Buddhist heartland and were

actively engaged in the creation of texts, many of which lack direct literary parallels in Sanskrit and Pli. Gndhr texts that have been transmitted, translated,

transposed, and transformed from other Buddhist literary traditions are often similar but not exactly identical to parallels in Pli and Sanskrit sources, particularly

Gndhr versions of verses of the Rhinoceros-stra and the Anavatapta-Gth

(Salomon 2000; 2008). Other Gndhr texts have complex intertextual relationships, including three Ekotarrikgama-type stras (Allon 2001), two of which have

direct literary parallels with Pli texts in the Aguttara Nikya, but the second of

the three stras, the Budhabayaa (Buddhavacana) stra, has no parallel.8 Among

four Gndhr Sayuktgama stras in the Senior collection (Glass 2007), the first

stra (Saa-stra) lacks a direct parallel and the description of the perception of

non-delight in the entire world (sarvaloge aaviraa saa) appears to be unique.

Original compositions of Gndhr commentaries in the British Library collection

adopt exegetical techniques similar to Pli traditions but seem to represent a very

early stage in the categorical reduction (Baums 2009) of doctrinal concepts, such

as the Four Truths. Mahyna and Vinaya texts were not identified in the British

Library and Senior collections of Gndhr manuscripts, but subsequent access to

Vinaya fragments and Mahyna and proto-Mahyna Pure Land and Perfection

of Wisdom texts in the Bajaur and Split collections as well as identifications of

Bhadrakalpik-stra fragments in the Schyen Gndhr fragments clearly demonstrate that Vinaya and Mahyna texts were circulating in Gandhra as early as

the first three centuries ce.9

Gndhr manuscripts preserve several narratives about the Buddhas present

and previous lives, with expected overlaps and surprising discrepancies with motifs

in Gandhran Buddhist art. Several Gndhr texts in the Senior scrolls preserve

hagiographical accounts of kyamunis awakening at Bodh Gaya, including the

6244-264.indb 255

1/16/2014 8:20:05 PM

256 Jason Neelis

conversion of Sujta and her family and donations by the two merchants Trapua

(Trivua) and Bhallika (Valia), a scene that is also depicted in Gandhran sculptures (Allon 2007: 1718, 2425; 2013). Almost fifty Prvayogas and Avadnas

in Kharoh manuscripts of the British Library collection are informal summaries

written by two specialist scavenger scribes as original compositions and probably served as memory aids for oral expansion (Lenz 2003: 1028; Salomon 1999:

35). Prvayogas link stories of the past with the present lives of figures such as

Ananda and Ajta Kauinya, while Avadnas tend to focus on the present lives,

although many Avadnas are karmic tales explaining how current conditions

resulted from past actions. Avadnas and Prvayogas with Gandhran historical characters from the contemporary context of the first century ce demonstrate

literary domestication of Buddhist narratives in Gandhra (Lenz 2010: 8293;

Neelis 2008; Salomon 1999: 14149). Allusions to prominent figures such as the

Great Satrap (Mahakatrapa) Jihoniga in Gandhra (gadharami),10 who is also

known from first-century ce coins and an inscribed vessel from Taxila, and to

Apavarman, a member of the Apraca dynasty attested in first-century ce coins

and an inscribed silver saucer from Taxila who helps to make arrangements for

sheltering monks during the rainy season (Salomon 1999: 14549; Lenz 2010:

8593), were likely intended to acknowledge their religious patronage and to

appeal to contemporary Gandhran audiences. Other figures with Indo-Iranian

names, such as Zadamitra, who is the protagonist in the Avadna with Apavarman

and makes a vow to become awakened after discussing the disappearance of the

True Dharma (Saddharma) in the preceding Avadna, also tend to be favorably

depicted. Timothy Lenz (2003: 18291) connects the Avadna of Zadamitra with

a dialogue between a aka (Indo-Scythian) and a monk in which the aka vows

to become an Arhat in a Prvayoga set in Taxila. The roles of these characters as

aspiring devotees of Buddhism contrast with other Buddhist ex eventu prophecies

associating the True Dharmas disappearance with an invasion by foreign kings,

including akas, Parthians, and Greeks (Lenz 2013). Although these original compositions with contemporary historical figures present interpretive difficulties due

to the lack of direct literary parallels, they provide a glimpse of how Gandhran

Buddhist storytellers and scribes adapted narratives to local settings in order

to attract potential patrons, including akas, Kuas, and Huns.

VISUAL NARRATIVES OF JTAKAS IN

GANDHRAN BUDDHIST ART

Hagiographical scenes from kyamuni Buddhas lifetime are more commonly

represented in Gandhran sculptures than his previous birth narratives, but about a

dozen Jtakas have been identified, typically in secondary or subsidiary positions

(Foucher 19051957: 1.27079, 2.1626; Odani 2008; Zwalf 1996: 13445).

However, Avadna and Prvayoga narratives in Gndhr fragments of the British

Library collection do not seem to correspond with Jtakas depicted in Gandhran

sculptures, with the single exception of a story of the Buddhas previous birth

6244-264.indb 256

1/16/2014 8:20:05 PM

Narratives in Buddhist Manuscripts 257

as Sudaa who gave everything away (an abbreviated version of the widespread

Vessantara/Vivantara Jtaka).11 This apparent discrepancy between Gndhr

manuscripts and visual culture of Gandhran Buddhist art is both surprising and

intriguing, since literary and artistic media belonging to approximately the same

period (early centuries ce) of regional Buddhist cultural production localize different sets of narratives in Gandhra. A Jtaka in which a Brahman student named

Megha or Sumati worships the previous Buddha Dpakara and vows to be reborn

as the Buddha is the most widely depicted previous-birth story in Gandhra and

appears as a prelude to the main narrative events of the Buddhas life.12 Gandhran

sculptures depict stories of other previous births of the Buddha as yma, a hermits son who was mortally wounded by a king while hunting but revived by

Indra,13 and as the sage Ekaga or Ryarga, who was the son of a singlehorned antelope (Foucher 19051951: 2.2023). Stories of previous births of

the Buddha as the merchant Maitrakanyaka,14 the Kinnara Candra,15 Amardev

in the Mah Umagga Jtaka (Odani 2008: 3013, Figure 26.7; Zwalf 1996: 58

n. 79), as well as nonhuman previous births as a deer (Ruru Jtaka) and an elephant with six tusks (aanta Jtaka) are also identified in Gandhran reliefs

based on similarities with literary versions in Pli and Sanskrit Buddhist texts and

iconographic parallels with narrative scenes in India and Central Asia (Foucher

19051951: 2.1620; Zwalf 1996: 5455). Visual narratives of bodily offerings

of King ibi (who gives away his flesh and eyes) and the Bodhisattva prince who

sacrifices himself to feed a hungry tigress and her cubs (Vyghr Jtaka) appear in

Gandhran art and in petroglyphs along the upper Indus River.16

The absence of these visual narratives in extant Gndhr manuscripts suggests

divergent lines of development of rebirth narratives in Gandhran literary and

visual cultures. Differences between selective appropriations of Buddhist rebirth

stories in Gandhran texts and art challenge assumptions that texts guide religious

iconography. The transmission of written and visual narratives selected from a

wider range of stories that were circulating through the northwestern borderlands

between South Asia and Central Asia by Gandhran artisans and scribes was

guided by various considerations, including an impetus to localize the narratives

in regional contexts in order to attract patrons and pilgrims.

GANDHRAN ARCHAEOLOGY OF PILGRIMAGE:

CHINESE ACCOUNTS OF LOCALIZED NARRATIVES

Previous lives of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas identified with Gandhran shrines

attracted Buddhist pilgrims, including Chinese travelers who traveled from

Central Asia and through the northwestern borderlands in the fifth to seventh centuries ce. Descriptions of places associated with the Buddhas relics and previous

lives in accounts of Faxian, Song Yun, and Xuanzang have aided in interpreting

Gandhran Buddhist art and identifying archaeological sites of stpas and monasteries. Narratives depicted in Gandhran art that can be localized at specific

shrines in Gandhra and neighboring regions based on Chinese accounts include

6244-264.indb 257

1/16/2014 8:20:06 PM

258 Jason Neelis

the Dpakara Jtaka in ancient Nagarhra (modern Jalalabad in northeastern

Afghanistan) and the Vivantara story near Shhbzgh or Shahr-i Bahlol in the

Peshawar valley.17 King ibis sacrifice of his flesh and his eyes are associated

with multiple sites in different regions ranging from Swat to the vicinity of the

upper Indus River and the outskirts of Taxila, where the princes bodily offering to

the tigress in the Vyghr Jtaka is also localized in Faxians account. Based on his

reconstruction of Xuanzangs itinerary from ancient Pukalvat to the Swat valley, Alfred Foucher (1915: 346) located a stpa associated with the yma Jtaka

at Periano her north of Charsada. The Ekaga Jtaka of the hermit who was

the antelopes son may be linked with ruins below the Shahkot Pass connecting

Gandhra with the Swat valley (Zwalf 1996: 55; Dehejia 1997: 201). Although

tienne Lamotte (1988 [1958]: 335, 442) considered these pilgrimage accounts

linking narratives of the Buddhas previous lives to various shifting locations to be

ahistorical imaginings,18 they quite clearly reflect Buddhist strategies to establish

geographical connections between the Gandhran region and kyamuni Buddha,

Bodhisattvas, and prominent Buddhist figures belonging to various past periods.

Localization of rebirth narratives (as well as bodily and other relics) enhanced the

importance of certain pilgrimage places and probably contributed to the formation

of regional Buddhist identity.

CONCLUSIONS ABOUT DISCONNECTIONS BETWEEN

GANDHRAN LITERARY AND VISUAL NARRATIVES

IN MANUSCRIPTS AND MATERIAL CULTURE

The employment of written and visual media to transmit Buddhist rebirth narratives complicates rather than clarifies shifting patterns of representation. The view

of Gandhran Buddhism from studying manuscript fragments with abbreviated

versions of Avadna and Prvayoga stories (which are now accessible in publications of the Gandhran Buddhist Texts series, but were not previously available

to scholars of Gandhran art history) does not perfectly align with earlier studies

of Jtakas in Gandhran art. A disconnection between the extant written summary stories in the British Library Kharoh fragments and the corpus of Jtaka

illustrations in Gandhran sculptures raises more questions instead of permitting

straightforward conclusions.

Nevertheless, patterns of selection reflect similar processes of localizing previous-birth narratives in Gandhra in order to domesticate the Dharma through

literary as well as material production. Stories such as the Vivantara Jtaka/

Sudaa Prvayoga, which were imported from northern India and adapted to

Gandhran settings, indicate the importance of establishing ties between the Buddhist heartland and the Northwest. Original Gndhr compositions of Avadnas

with contemporary local characters like Mahkatrapa Jihonika, the Apraca

Apavarman, Zadamitra, and an anonymous aka (as well as numerous other

figures with Indo-Iranian names and titles) reflect the multicultural distinctiveness of Gandhran Buddhism. Incorporation of powerful patrons with exogenous

6244-264.indb 258

1/16/2014 8:20:06 PM

Narratives in Buddhist Manuscripts 259

backgrounds is also reflected in the hybrid style of Gandhran Buddhist art, which

blends Indian, Iranian, Hellenistic, Central Asian, and local features in a manner

designed to appeal to the tastes of diverse regional audiences. Locative tendencies in Gandhran Buddhist texts and art went hand-in-hand with institutional

consolidation and expansion in the northwestern borderlands of South Asia, where

cultural production peaked during periods of aka, Kua, and Alchon Hun rule

in approximately the first five centuries ce. Re-contextualizations of narratives

in written and visual media honed in the Gandhran laboratory demonstrated

strategies that were successfully adopted for further translocations of Buddhist

narratives across Central and East Asia.

Apparent differences between Avadna and Prvayoga stories selected for written

summary in manuscripts and the limited number of Jtakas illustrated in Gandhran

art (particularly in contrast with numerous Jtakas at Bhrhut) would seem to suggest that scribes and artisans working in their own media had their own unique

considerations. In both cases, however, oral storytelling traditions underlie these

considerations, since (as Timothy Lenz [2003: 8591] points out in his analysis of

formulae in manuscript fragments calling for detailed expansion of Avadnas and

Prvayogas) written summaries reflect a transitional phase between oral and written

transmission and the visual form may have been more amenable to innovation than

fixed texts (Santoro 1999). Despite differences in the selection of narratives (with

the single exception of the story of Vivantara/Sudaa), it is interesting to note that

genres of previous-birth stories in both literary and visual media occupied secondary positions: In Gandhran manuscripts, scavenger scribes wrote Prvayogas and

Avadnas in leftover spaces at the bottom of the recto and on the verso of birchbark scrolls, while (apart from Dpakara Jtaka panels in sequences depicting

hagiographical episodes from kyamuni Buddhas present life-story), small Jtaka

reliefs in Gandhran sculptures tend to belong to subsidiary architectural elements

(for example, stair-risers) rather than the path of circumambulation around stpas.

The placement of Avadnas, Prvayogas, and Jtakas may support the impression that previous-birth narratives were eclipsed by hagiographical narratives of

kyamunis lifetime during the early centuries ce in Gandhra. The Avadna/

Prvayoga genre is prominently represented in the British Library collection of

Gndhr fragments from the first century ce and in about 300 fragments in the

Split collection (not treated here) with radiocarbon dates in the second to first

century bce range (Falk 2011: 20, Figure 5). However, this informal variety of

secondary narrative summaries is not found among the Gndhr texts represented

in the Bajaur, Senior, and Schyen collections belonging to somewhat later periods. Parallels for Gndhr Avadnas with local figures and regional settings in

the British Library collections are very difficult to identify in other Buddhist

literary traditions and do not seem to have been included in thematically organized genre bundles like the Avadnaataka and Jtakaml but, instead, may

belong to an early phase in the development of Buddhist rebirth story literature

before formal conventions were standardized in extant Pli and Sanskrit texts.

On the other hand, several hagiographic narratives recounting events connected

with kyamunis awakening (such as the gift of the two merchants and Sujtas

6244-264.indb 259

1/16/2014 8:20:06 PM

260 Jason Neelis

offering) are among the texts belonging to the Senior collection, which is firmly

dated in the second century ce. Such a chronological shift in the type of narratives

written in Gndhr manuscripts might correspond with art-historical distinctions

between the relatively limited visual repertoire of Gandhran Jtaka reliefs and

more prevalent illustrations of kyamunis hagiographical events, as well as a

proliferation in the production of Gandhran Buddha images.

While suggestions for chronological implications are tentative and direct relationships between the emerging corpus of Avadna and Prvayoga narratives

preserved in Gandhran manuscripts and Jtakas in Gandhran narrative reliefs

remain elusive, these stories transmitted in written and visual media clearly fulfilled religious purposes. As Peter Skilling (2008: 68) emphasizes in connecting

the marks of the Buddhas body to ethical karmic acts in the series of previous

lives recalled in rebirth narratives, The jtakas have, in a sense, culminated in

the image. Jtakas, Avadnas, and Prvayogas serve as exemplary models for

emulating the Buddhas attainments by promulgating doctrines, justifying ethical

norms, and stimulating generous donations. Literary and visual narratives of past

and present lives in Gandhran manuscripts and material culture of images functioned as catalysts for achieving individual and institutional aspirations.

NOTES

6244-264.indb 260

1. Foucher (19051951: 2.41220; 19421947: 2.27980), Fussman (1994: 4344),

and Lamotte (1958/1988: 44142) discuss the institutionalization of sacred topography in Gandhra. Studies of Buddhist pilgrimage in the Indo-Tibetan borderlands by Huber (1999) and in medieval China by Robson (2009) have emphasized

processes for translocating Buddhist relics and narratives to regions outside of the

historical Buddhas homeland by drawing upon theories of locativizing tendencies

in the history of religions developed by Jonathan Z. Smith (1987; 2004).

2. Synthetic treatments of sources for the study of Gandhran Buddhism include a

succinct overview by Dietz (2007), articles on Gandhran art, archaeology, texts,

and coins edited by Behrendt and Brancaccio (2006), and an exceptional catalog of

Gandhran Buddhist art and archaeology in Pakistan (Luczanits 2008). An annotated bibliography on Gandhran Buddhism is available online from Oxford Bibliographies OnlineBuddhism (Neelis 2013).

3. Aokan inscriptions in the Northwest at Shahbazgarhi, Mansehra, and Kandahar

are not addressed to Buddhist audiences, unlike some Aokan inscriptions at Buddhist shrines such as Lumbini and others directed to Buddhist communities in India.

Fussman (1994: 19) is skeptical about attributions of the founding of Dharmarjika

stpas at Taxila and elsewhere in the Northwest to Aoka by later Chinese visitors

and by Buddhist literary traditions (Strong 2004: 13637), since archaeological

evidence belongs to the second century bce rather than the period of Aokas rule.

4. Fouchers (19051951 and 19421947) works remain important points of departure. Filliozat and Leclant (2009) include assessments of Fouchers legacy with a

list of his publications. Deydier (1950), Guene et al. (1998), and Zwalf (1996:

6776) provide detailed bibliographies on Gandhran art history.

5. See Richard Manns contribution to this volume.

6. A searchable online Catalog of Kharoh Inscriptions maintained by Stefan Baums

and Andrew Glass is a valuable resource, which updates Sten Konows (1929) edition of around 140 Kharoh inscriptions.

1/16/2014 8:20:06 PM

Narratives in Buddhist Manuscripts 261

7. The Khotan version of a Gndhr Dharmapada was edited by John Brough (1962).

Since Richard Salomons (1999) overview of the British Library collection, scholarly

editions of Gndhr versions of the Rhinoceros Stra (Salomon 2000), Anavataptagth (Salomon 2008), Ekottarkgama-type stras (Allon 2001), Dharmapada

fragments, previous-birth stories, and Avadnas (Lenz 2003; 2010) have appeared

in the Gandhran Buddhist Texts series, along with manuscripts belonging to the

Senior collection (Salomon 2003; Glass 2007). Gndhr manuscripts belonging to

the Schyen collection (Allon and Salomon 2000), the Bajaur collection (Strauch

2008), and the Split collection (Falk 2011), as well as smaller collections are

described by Mark Allon (2008).

8. Allon 2001: 89 (1.3) suggests that since all three stras are associated with the

number 4, they may have belonged to a Gndhr section on fours, but there does

not seem to be any thematic relationship between them. The Budhabayaa-stra

dealing with the four postures (going, standing, sitting, and lying down awake) is

similar to suttas 11 and 12 of the Pli Catukka-nipta (Aguttara-nikya II 1315).

These suttas are thematically and sequentially related to the Pli parallel (sutta

14) for the Gndhr Prasaa-stra, which follows the Budhabayaa-stra (Allon

2001: 22443, 9).

9. Strauch (2008: 115) addresses Vinaya fragments in the Bajaur collections, which

in his view do not belong to a particular mainstream affiliation. Allon and Salomon

(2010), Strauch (2010), and Falk and Karashima (2012; 2013) discuss recent identifications of Mahyna texts in Gndhr manuscripts belonging to the Schyen,

Bajaur, and Split collections.

10. Lenz (2010: 9698) re-edits an avadna in British Library fragment 2 (pl. 20),

which was previously discussed by Salomon (1999: 14145) (the fragment is illustrated on the cover of Salomon [1999]). Lenz (2010: 98) tentatively suggests that

Buddhist relics or the Dharma was transported widely (ve[stra]gena bahadi) in

Gandhra (gadharami) during the reign of Jihoniga.

11. Anderl and Pons Forthcoming, chapter 2; Dehejia 1997: 199, fig. 185; Lenz 2003:

15765; Odani 1999: 303, fig. 26.6; Zwalf 1996: 14245, catalogue nos. 13740.

12. Dehejia 1997: 25, 186; Pons 2011: 2.4160; Odani 1999: 3003, figs. 26.45; Zwalf

1996: 54, 13438, catalogue nos. 12731.

13. Anderl and Pons Forthcoming, chapter 3; Dehejia 1997: 19799, fig. 184; Zwalf

1996: 13839, catalogue nos. 13233.

14. Foucher 1919: 1819; Zwalf 1996: 13940, catalogue no. 134.

15. Foucher 1919: 2326; Zwalf 1996: 14041, catalogue no. 135.

16. Bandini 2003: 4349, 11822; Bandini-Knig and Fussman 1997: 17879;

Foucher 1919: 1718; Thewalt 1983; Zwalf 1996: 14142, catalogue no. 136.

17. The distribution of larger images of the Dpakara Jtaka found in Kabul valley of

ancient Kapi and Vivantara reliefs in the Peshawar valley seem to reflect these

localizations, according to information from Jessie Pons.

18. Compare Foucher (1915: 28) on conversion of Hrit in Ancient Geography of

Gandhara: this will not be the only legend which originated in Central India and

which we shall find acclimatized in Gandhra by Buddhist missionaries.

19.

REFERENCES

Allon, Mark. 2001. Three Gndhr Ekottarkgama-type Sutras: British Library Kharoh

Fragments 12 and 14. Gandhran Buddhist Texts 2. Seattle.

Allon, Mark. 2007. Introduction: The Senior Manuscripts. In Four Gandhari

Samyuktagama Sutras: Senior Kharosth Fragment 5, 325, by Andrew Glass.

Gandharan Buddhist Texts 4. Seattle.

6244-264.indb 261

1/16/2014 8:20:06 PM

262 Jason Neelis

Allon, Mark. 2008. Recent Discoveries of Buddhist Manuscripts from Afghanistan and

Pakistan and their Significance. In Art, Architecture and Religion: Along the Silk Roads,

ed. Kenneth Parry, 15378. Silk Road Studies 12. Turnhout.

Allon, Mark. 2013. A Gndhr Version of the Story of the Merchants Tapussa and Bhallika.

Bulletin of the Asia Institute 23: 920.

Allon, Mark and Richard Salomon. 2000. Kharoh Fragments of a Gndhr Version

of the Mahparinirvastra. In Buddhist Manuscripts 1, ed. Jens Braarvig, 24373.

Manuscripts in the Schyen Collection 1. Oslo.

Allon, Mark and Richard Salomon. 2010. New Evidence for the Mahyna in Early

Gandhra. Eastern Buddhist 41: 122.

Anderl, Christoph and Jessie Pons. Forthcoming. Dynamics of Text Corpora and Image

Programs: Representations of Buddhist Narratives Along the Silk Route.

Bandini, Ditte. 2003. Die Felsbildstation Thalpan. Materialien zur Archologie der Nordgebiete Pakistans 6. Mainz.

Bandini-Knig, Ditte and Grard Fussman. 1997. Die Felsbildstation Shatial. Materialien

zur Archologie der Nordgebiete Pakistans 2. Mainz.

Baums, Stefan. 2009. A Gndhr Commentary on Early Buddhist Verses: British Library

Kharoh Fragments 7, 9, 13 and 18. PhD diss., University of Washington.

Baums, Stefan and Andrew Glass. Catalog of Gndhr Texts: Manuscripts, Dictionary of

Gndhr, and Catalog of Kharoh Inscriptions. Accessed December 18, 2013. http://

gandhari.org/a_inscriptions.php.

Behrendt, Kurt A. and Pia Brancaccio, eds. 2006. Gandhran Buddhism: Archaeology, Art,

and Texts. Vancouver.

Brough, John. 1962. The Gndhr Dharmapada. London Oriental Series 7. London; New

York.

Dehejia, Vidya. 1997. Discourse in Early Buddhist Art: Visual Narratives of India. New

Delhi.

Deydier, Henri. 1950. Contribution a letude de lart du Gandhra. Paris.

Dietz, Siglinde. 2007. Buddhism in Gandhra. In The Spread of Buddhism, ed. Ann Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacher, 4974. Handbuch der Orientalistik 16. Leiden.

Falk, Harry. 2011. The Split Collection of Kharoh Texts. Ska daigaku kokusai

bukkygaku kt kenkyjo nenp (Annual Report of the International Research Institute

for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University) 14: 1323.

Falk, Harry and Seishi Karashima. 2012. A First-Century Prajpramit Manuscript

from Gandhraparivarta 1 (Texts from the Split Collection 1). Ska daigaku kokusai

bukkygaku kt kenkyjo nenp (Annual Report of the International Research Institute

for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University) 15: 1961.

Falk, Harry and Seishi Karashima. 2013. A First-Century Prajpramit Manuscript

from Gandhraparivarta 5 (Texts from the Split Collection 2). Ska daigaku kokusai

bukkygaku kt kenkyjo nenp (Annual Report of the International Research Institute

for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University) 16: 97169.

Filliozat, Pierre-Sylvain and Jean Leclant, eds. 2009. Bouddhismes dAsieMonuments et

Littratures. Paris.

Foucher, Alfred. 1915 [1901]. Notes on the Ancient Geography of Gandhra: A Commentary on a Chapter of Hiuan Tsang, trans. Harold Hargreaves, 32269. Calcutta.

Foucher, Alfred. 19051951. Lart grco-bouddhique du Gandhra; tude sur les origines de linfluence classique dans lart bouddhique de lInde et de lExtrme-Orient. 3

volumes. Paris.

Foucher, Alfred. 1919. Les representations de Jtaka dans lart bouddhiques. Mmoires

concernant lAsie Orientale 3: 152.

Foucher, Alfred. 19421947. La vieille route de lInde de Bactres Taxila. 2 vols. Mmoires

de la Dlgation archologique franaise en Afghanistan 1. Paris.

Fussman, Grard. 1994. Upya-kaualya: Limplantation du bouddhisme au Gandhra. In

Bouddhisme et cultures locales, ed. Fukui Fumimasa and Grard Fussman, 1751. Paris.

6244-264.indb 262

1/16/2014 8:20:06 PM

Narratives in Buddhist Manuscripts 263

Glass, Andrew. 2007. Four Gndhr Samyuktgama Sutras: Senior Kharoh Fragment

5. Gandhran Buddhist Texts 4. Seattle.

Guenee, Pierre, Francine Tissot, and Pierfrancesco Callieri. 1998. Bibliographie analytique

des ouvrages parus sur lart du Gandhara entre 1950 et 1993. Paris.

Huber, Toni. 1999. The Cult of Pure Crystal Mountain: Popular Pilgrimage and Visionary

Landscape in Southeast Tibet. New York.

Konow, Sten. 1929. Kharoshh Inscriptions, with the exception of those of Aoka. Corpus

Inscriptionum Indicarum, 2, part 1. Calcutta.

Lamotte, tienne. 1988 [1958]. History of Indian Buddhism: From the Origins to the aka

Era. Publications de lInstitut orientaliste de Louvain, 36. Louvain-la-Neuve.

Lenz, Timothy. 2003. A New Version of the Gndhr Dharmapada and a Collection of

Previous-birth Stories: British Library Kharoh fragments 16 + 25. Gandhran Buddhist Texts 3. Seattle.

Lenz, Timothy. 2010. Gandhran Avadnas: British Library Kharohi Fragments 13

and 21 and Supplementary Fragments AC. Gandhran Buddhist Texts 6. Seattle.

Lenz, Timothy. 2013. Ephemeral Dharma; Magical Hope. Bulletin of the Asia Institute 23: 13543.

Lders, Heinrich. 1963. Bhrhut inscriptions. Ootacamund.

Luczanits, Chistian, ed. 2008. Gandhara, the Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan: Legends, Monasteries, and Paradise. Bonn.

Meister, Michael. 2010. Palaces, Kings, and Sages: World Rulers and World Renouncers in

Early Buddhism. In From Turfan to Ajanta, ed. Eli Franco and Monika Zin, 2.65170.

Lumbini.

Neelis, Jason. 2008. Historical and Geographical Contexts for Avadnas in Kharoh Manuscripts. In Buddhist Studies, ed. Richard Gombrich and Cristina A. Scherrer-Schaub,

15167. Delhi.

Neelis, Jason. 2011. Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and

Exchange within and beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. Dynamics

in the History of Religion 2. Leiden.

Neelis, Jason. 2013. Buddhism in Gandhara. In Oxford Bibliographies in Buddhism, ed.

Richard Payne. Oxford Bibliographies Online. New York.

Odani Nakao. 2008. Jtakas Represented in Gandhra Art. In South Asian Archaeology

1999, ed. Ellen Raven, 297304. Grningen.

Pons, Jessie. 2011. Inventaire et tude systmatiques des sites et des sculptures bouddhiques du Gandhra. PhD diss., Universit Paris-Sorbonne.

Przyluski, Jean. 1914. Le nord-ouest de lInde dans le Vinaya des Mla-Sarvstivda et les

texts apparents. Journal Asiatique 4, ser. 11: 493568.

Robson, James. 2009. Power of Place: The Religious Landscape of the Southern Sacred

Peak (Nanyue) in Medieval China. Cambridge, Mass.

Salomon, Richard. 1999. Ancient Buddhist Scrolls from Gandhra: The British Library

Kharoh Fragments. Seattle.

Salomon, Richard. 2000. A Gndhr Version of the Rhinoceros Sutra: British Library

Kharoh Fragment 5B. Gandhran Buddhist Texts 1. Seattle.

Salomon, Richard. 2003. The Senior Manuscripts: Another Collection of Gandhran Buddhist Scrolls. Journal of the American Oriental Society 123.1: 7392.

Salomon, Richard. 2008. Two Gndhr Manuscripts of the Songs of Lake Anavatapta

(Anavatapta-gth): British Library Kharoh Fragment 1 and Senior Scroll 14.

Gandharan Buddhist Texts 5. Seattle.

Santoro, Arcangela. 1999. A Note on the Problem of the Relationships between Literary

Narrative, Visual Narrative and Oral Narrative in Gandhran art. Silk Road Art and

Archaeology 6: 6167.

Schlingloff, Dieter. 1982. Erzhlung und Bild. Beitrge zur allgemeinen und vergleichenden Archologie 3: 87213.

Schlingloff, Dieter. 2000. Ajanta: Handbuch der Malereien/Handbook of the Paintings.

Part 1: Erzhlende Wandmalereien/Narrative Wall-paintings. 3 vols. Wiesbaden.

6244-264.indb 263

1/16/2014 8:20:06 PM

264 Jason Neelis

Skilling, Peter. 2008. Narrative, Art and Ideology: Jtakas from India to Southeast Asia. In

Past Lives of the Buddha: Wat Si ChumArt, Architecture and Inscriptions, ed. Peter

Skilling, 59104. Bangkok.

Smith, Jonathan Z. 1987. To Take Place: Toward Theory in Ritual. Chicago.

Smith, Jonathan Z. 2004. Relating Religion: Essays in the Study of Religion. Chicago.

Strauch, Ingo. 2008. The Bajaur Collection of Kharoh ManuscriptsA Preliminary Survey. Studien zur Indologie und Iranistik 25: 10336.

Strauch, Ingo. 2010. More Missing Pieces of Early Pure Land Buddhism: New Evidence

for Akobhya and Abhirati in an Early Mahyna Stra from Gandhra. Eastern Buddhist 41: 2366.

Strong, John. 2004. Relics of the Buddha. Princeton.

Taddei, Maurizio. 1999. Oral Narrative, Visual Narrative, Literary Narrative in Ancient

Budddhist India. In India, Tibet, China: Genesis and Aspects of Traditional Narrative,

ed. Alfredo Cadonna, 7186. Orientalia venetiana 7. Firenze.

Thewalt, Volker. 1983. Jtaka-Darstellungen bei Chilas und Shatial am Indus. In Ethnologie und Geschichte: Festschrift fr Karl Jettmar, ed. Peter Snoy, 62234. Beitrge zur

Sdasienforschung, 86. Wiesbaden.

Zwalf, Wladimir. 1996. A Catalogue of the Gandhra Sculpture in the British Museum.

2 vols. London.

6244-264.indb 264

1/16/2014 8:20:06 PM

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Journey of CivilizationDokument4 SeitenJourney of Civilizationhusankar2103100% (2)

- Dumouchel 1988 Violence and Truth On The Work of Rene GirardDokument147 SeitenDumouchel 1988 Violence and Truth On The Work of Rene GirardLinda LeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cole, Alan 1998 Mothers and Sons in Chinese BuddhismDokument190 SeitenCole, Alan 1998 Mothers and Sons in Chinese BuddhismLinda Le100% (2)

- Bal Mieke Performance and Performativity From Travelling Concepts in The Humanities A Rough Guide1 PDFDokument22 SeitenBal Mieke Performance and Performativity From Travelling Concepts in The Humanities A Rough Guide1 PDFLinda LeNoch keine Bewertungen

- R. D. Banerji - Prehistoric Ancient Hindu IndiaDokument369 SeitenR. D. Banerji - Prehistoric Ancient Hindu IndiaAmit Pathak100% (3)

- Banerjee, Anukul Chandra1957 Sarvastivada Literature PDFDokument283 SeitenBanerjee, Anukul Chandra1957 Sarvastivada Literature PDFLinda Le100% (2)

- Structuraldesignofthebuildings PDFDokument39 SeitenStructuraldesignofthebuildings PDFEmilija MitevskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gandhara Art: An Appraisal: Tauqeer Ahmad WarraichDokument19 SeitenGandhara Art: An Appraisal: Tauqeer Ahmad Warraichsampa boseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theme IVDokument66 SeitenTheme IVjunaid khanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 001 TheCultural History of GandhaDokument3 Seiten001 TheCultural History of GandhaDr. Abdul Jabbar KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- From The Panchatantra To La Fontaine: Migrations of Didactic Animal Illustration From India To The West - Simona Cohen and Housni Alkhateeb ShehadaDokument64 SeitenFrom The Panchatantra To La Fontaine: Migrations of Didactic Animal Illustration From India To The West - Simona Cohen and Housni Alkhateeb ShehadaCecco AngiolieriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short Note On Gandhara School of Art and ArchitectureDokument4 SeitenShort Note On Gandhara School of Art and ArchitectureviplavMBA100% (2)

- Buddhism in Andhra PradeshDokument10 SeitenBuddhism in Andhra PradeshBommuSubbarao0% (1)

- The Lost Arts of IndiaDokument6 SeitenThe Lost Arts of IndiasamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Genre and Devotion in Punjabi Popular Narratives Rethinking Cultural and Religious SyncretismDokument32 SeitenGenre and Devotion in Punjabi Popular Narratives Rethinking Cultural and Religious Syncretismhamad abdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surdas and KeshavdasDokument16 SeitenSurdas and KeshavdasJigmat WangmoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ben-Herut - Figuring The South-Indian S Ivabhakti Movement - The Broad Narrative Gaze of Early Kannada Hagiographic LiteratureDokument22 SeitenBen-Herut - Figuring The South-Indian S Ivabhakti Movement - The Broad Narrative Gaze of Early Kannada Hagiographic LiteratureEric M GurevitchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Art, Artists, and Its Historical Perspective: International Journal of Academic Research and DevelopmentDokument6 SeitenIndian Art, Artists, and Its Historical Perspective: International Journal of Academic Research and DevelopmentsantonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 12Dokument11 SeitenUnit 12amanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asko Parpola, The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans andDokument4 SeitenAsko Parpola, The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans andSatyam KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daoist Body Cultivation Traditional ModeDokument4 SeitenDaoist Body Cultivation Traditional ModeTaehyung's GUCCI clothesNoch keine Bewertungen

- When The Greeks Converted The Buddha - HalkiasDokument55 SeitenWhen The Greeks Converted The Buddha - HalkiasMichael MuhammadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Vedic Traditions....Dokument6 SeitenPre-Vedic Traditions....Sharon TiggaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian Xuanzang and Yijing Sources For Cross Cultural Encounters Between Ancient China and Ancient IndiaDokument10 SeitenThe Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian Xuanzang and Yijing Sources For Cross Cultural Encounters Between Ancient China and Ancient IndiaMay KongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gandhara TahzeebDokument2 SeitenGandhara TahzeebFarooq TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Topic 1Dokument8 SeitenAncient Topic 1saqib nawazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 8 Vedic Period-I : 8.0 ObjectivesDokument12 SeitenUnit 8 Vedic Period-I : 8.0 ObjectivesRajat KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10.4324 9781003258575-6 ChapterpdfDokument32 Seiten10.4324 9781003258575-6 Chapterpdf- TvT -Noch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Cultural DynamicsDokument30 SeitenIndian Cultural DynamicsSergeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2457 2452 1 PBDokument31 Seiten2457 2452 1 PBcekrikNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Nehu Journal Jan June 2018-59-83Dokument25 SeitenThe Nehu Journal Jan June 2018-59-83Sachchidanand KarnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- On The History and The Present State of Vedic Tradition in NepalDokument23 SeitenOn The History and The Present State of Vedic Tradition in NepalRjnbkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Indian Folk Culture in Promotion of Tourism in The CountryDokument5 SeitenRole of Indian Folk Culture in Promotion of Tourism in The CountryRamanasarmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Cultural and Historical FormationsDokument8 SeitenEarly Cultural and Historical FormationsBarathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art and Archetecture AssignmentDokument12 SeitenArt and Archetecture AssignmentAnushree DeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mahima Rao-SEC AssignmentDokument12 SeitenMahima Rao-SEC Assignmentmahima raoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Panchatantrapdf AA 76-2 PDFDokument65 SeitenPanchatantrapdf AA 76-2 PDFSubraman Krishna kanth MunukutlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Power of The Heart That Blazes in The WorldDokument28 SeitenThe Power of The Heart That Blazes in The WorldAhmad AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abstract On DwarkaDokument2 SeitenAbstract On DwarkasatanshisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Indian History SourcesDokument11 SeitenAncient Indian History SourceszishanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topic Sources and Tools of Historical Reconstruction:: Class Lecture Prepared by Jamuna Subba Department of HistoryDokument6 SeitenTopic Sources and Tools of Historical Reconstruction:: Class Lecture Prepared by Jamuna Subba Department of HistorySiddharth TamangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gandhara ArtDokument25 SeitenGandhara ArtSIBAT ul Hassan100% (1)

- Ijhss - Sculptural Art of Jains in Odisha A StudyDokument12 SeitenIjhss - Sculptural Art of Jains in Odisha A Studyiaset123100% (1)

- Narrative Devices in The Buddhist Canonical Avadanas and JatakasDokument3 SeitenNarrative Devices in The Buddhist Canonical Avadanas and Jatakasguna ratanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Historic Sources: Literary and ArcheologicalDokument19 SeitenHistoric Sources: Literary and ArcheologicalSaloniNoch keine Bewertungen

- History-I, Reading Material 2021Dokument41 SeitenHistory-I, Reading Material 2021ricardo ryuzakiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alexander CunninghamDokument30 SeitenAlexander CunninghamAnjnaKandari100% (1)

- Hidden Realms and Pure Abodes - Central Asian Buddhism As Frontier Religion in The Literature of India, Nepal, Tibet - Ronald M. DavidsonDokument30 SeitenHidden Realms and Pure Abodes - Central Asian Buddhism As Frontier Religion in The Literature of India, Nepal, Tibet - Ronald M. Davidsonindology2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Cultural Landscapes - Religious Pluralism, Tolerance and Ground Reality - Architexturez South AsiaDokument9 SeitenIndian Cultural Landscapes - Religious Pluralism, Tolerance and Ground Reality - Architexturez South AsiaTanushree Roy PaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- 107 209 1 SM PDFDokument52 Seiten107 209 1 SM PDFjohnnirbanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book Review Text and Tradition in SouthDokument5 SeitenBook Review Text and Tradition in South23scms02Noch keine Bewertungen

- How To Do Multilingual HistoryDokument22 SeitenHow To Do Multilingual Historyhamad abdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- IWIL 2022 Test 1 GS 1 Art & Culture, Modern India, World HistoryDokument40 SeitenIWIL 2022 Test 1 GS 1 Art & Culture, Modern India, World HistoryDaniel HoffNoch keine Bewertungen

- History Upto MathuraDokument29 SeitenHistory Upto MathuraH MaheshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sources of Ancient Indian HistoryDokument5 SeitenSources of Ancient Indian HistoryRamita Udayashankar100% (1)

- SEC AssignmentDokument5 SeitenSEC AssignmentChandra Prakash DixitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dionysus and Drama in The Buddhist Art of GandharaDokument26 SeitenDionysus and Drama in The Buddhist Art of Gandhara- TvT -Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tibetan Buddhist Meditational Art of BuryatiaDokument50 SeitenTibetan Buddhist Meditational Art of BuryatiaCarmen Hnt100% (4)

- The Secrets of Tantric Buddhism: Understanding the Ecstasy of EnlightenmentVon EverandThe Secrets of Tantric Buddhism: Understanding the Ecstasy of EnlightenmentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dhrupad and BishnupurDokument15 SeitenDhrupad and BishnupurArijit BoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lakshika TyagiDokument6 SeitenLakshika TyagiLakshikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Puṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 4Von EverandPuṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 4Lucas den BoerNoch keine Bewertungen

- India in the Chinese Imagination: Myth, Religion, and ThoughtVon EverandIndia in the Chinese Imagination: Myth, Religion, and ThoughtBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (1)

- Heesternab 1985 Inner ConflictionDokument122 SeitenHeesternab 1985 Inner ConflictionLinda LeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broy 2012martial Monks in Medieval Chinese BuddhismDokument47 SeitenBroy 2012martial Monks in Medieval Chinese BuddhismLinda LeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chen 1973 A Comparative Study of The Founder's Authority The Community, and The Disciplines in Early Buddhism and in Early ChristianityDokument327 SeitenChen 1973 A Comparative Study of The Founder's Authority The Community, and The Disciplines in Early Buddhism and in Early ChristianityLinda LeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Newly Identified Khotanese Fragments in The British Library and Their Chinese ParallelsDokument16 SeitenNewly Identified Khotanese Fragments in The British Library and Their Chinese ParallelsLinda LeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catalogue of Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit BooksDokument327 SeitenCatalogue of Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit BooksLinda Le100% (1)

- Catalogue of The Tibetan Manuscripts From Tun-Huang in The India Office Library 1962 Bazuo Enoki Part IDokument31 SeitenCatalogue of The Tibetan Manuscripts From Tun-Huang in The India Office Library 1962 Bazuo Enoki Part ILinda LeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fritz Staal1993 Ritual and Mantras Rule Without MeaningDokument250 SeitenFritz Staal1993 Ritual and Mantras Rule Without MeaningLinda Le100% (1)

- Norman 1994 Asokan MiscellanyDokument11 SeitenNorman 1994 Asokan MiscellanyLinda LeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mair 1988 Painting and PerformanceDokument130 SeitenMair 1988 Painting and PerformanceLinda LeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Brahmins of Kashmir by Michael WitzelDokument56 SeitenThe Brahmins of Kashmir by Michael WitzelShankerThapaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Karashima, Features of The Underlying Language of Zhi Qian's Chinese Translation of The Vimalakīrtinirdeśa PDFDokument20 SeitenKarashima, Features of The Underlying Language of Zhi Qian's Chinese Translation of The Vimalakīrtinirdeśa PDFc1148627Noch keine Bewertungen

- Norman, K. R., Pali Philology & The Study of BuddhismDokument13 SeitenNorman, K. R., Pali Philology & The Study of BuddhismkhrinizNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Gandhari and Pali To Han Dynasty CHDokument2 SeitenFrom Gandhari and Pali To Han Dynasty CHTodd BrownNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gāndhārī - H. W. BaileyDokument35 SeitenGāndhārī - H. W. BaileyDeepro ChakrabortyNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of Indic Scripts 2016 PDFDokument15 SeitenHistory of Indic Scripts 2016 PDFclaudia_graziano_3100% (1)

- Journal of The American Oriental Society, Vol. 117, No. 2. (Apr. - Jun., 1997), Pp. 353-358Dokument7 SeitenJournal of The American Oriental Society, Vol. 117, No. 2. (Apr. - Jun., 1997), Pp. 353-358Михаил Мышкин ИвановичNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nepal - Nepali Mss Gandhari Chinese TR of SadharmapundarikaDokument37 SeitenNepal - Nepali Mss Gandhari Chinese TR of SadharmapundarikaShankerThapaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 胡 梵Dokument23 Seiten胡 梵Hung Pei YingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Karashima2014-Language of Abhisamacarika PDFDokument15 SeitenKarashima2014-Language of Abhisamacarika PDFSeishi KarashimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soka Annual Vol. XXIII (2020)Dokument275 SeitenSoka Annual Vol. XXIII (2020)VajradharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Levman-The Language The Buddha SpokeDokument45 SeitenLevman-The Language The Buddha SpokeAnandaNoch keine Bewertungen