Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

History of Religious Jewish Music

Hochgeladen von

Stacy JohnsonCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

History of Religious Jewish Music

Hochgeladen von

Stacy JohnsonCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

History of religious Jewish music

This article is about the sacred music of Judaism

from Biblical to Modern times. For Jewish secular music, including klezmer and Sephardic, as

well as the Jewish contribution to Western music, see Secular Jewish culture.

the Shofar, a hollowed-out rams horn;

Origin of Jewish music in the

Temple

the metziltayim, or cymbal;

the chatzutzera, or trumpet, made of silver;

the tof or small drum;

the paamon or bell;

the halil or big ute.

According to the Mishna, the regular Temple orchestra

consisted of twelve instruments, and the choir of twelve

male singers.

A number of additional instruments were known to the

ancient Hebrews, though they were not included in the

regular orchestra of the Temple: the uggav (small ute),

the abbuv (a reed ute or oboe-like instrument).

After the destruction of the Temple and the subsequent

diaspora of the Jewish people, there was a feeling of great

loss among the people. At the time, a consensus developed that all music and singing would be banned; this was

codied as a rule by some early Jewish rabbinic authorities. However, the ban on singing and music, although

not formally lifted by any council, soon became understood as only a ban outside of religious services. Within

the synagogue the custom of singing soon re-emerged.

In later years, the practice became to allow singing for

feasts celebrating religious life-cycle events such as weddings, and over time the formal ban against singing and

performing music lost its force altogether, with the exception of the Yemenite Jews. The Jews of Yemen mainSymbolic model of King Davids harp (or lyre) displayed in the tained strict adherence to Talmudic and Maimonidean

City of David, Jerusalem, Israel

halakha[1] and instead of developing the playing of musical instruments, they perfected singing and rhythm.[2]

The earliest synagogal music was based on the same sys(See Yemenite Jewish poetry. For the modern Yemenitetem as that used in the Temple in Jerusalem. According

Israeli musical phenomenon, however, see Yemenite Jewto the Talmud, Joshua ben Hananiah, who had served in

ish music.)

the sanctuary Levitical choir, told how the choristers went

to the synagogue from the orchestra by the altar (Talmud, It was with the piyyutim (liturgical poems) that Jewish

music began to crystallize into denite form. The cantor

Suk. 53a), and so participated in both services.

sang the piyyutim to melodies selected by their writer or

Biblical and contemporary sources mention the following

by himself, thus introducing xed melodies into synagoinstruments that were used in the ancient Temple:

gal music. The prayers he continued to recite as he had

heard his predecessors recite them; but in moments of in the Nevel, a 12-stringed harp;

spiration he would give utterance to a phrase of unusual

the Kinnor, a lyre with 10 strings;

beauty, which, caught up by the congregants.

1

1.1

Adaptations from local music

The music may have preserved a few phrases in the reading of Scripture which recalled songs from the Temple

itself; but generally it echoed the tones which the Jew of

each age and country heard around him, not merely in

the actual borrowing of tunes, but more in the tonality on

which the local music was based. These elements persist

side by side, rendering the traditional intonations a blend

of dierent sources.

The underlying principle may be the specic allotment

in Jewish worship of a particular mode to each sacred

occasion, because of some esthetic appropriateness felt to

underlie the association. In contrast to the meager modal

choice of modern melody, the synagogal tradition revels

in the possession of a of scale-forms preserved from the

remote past, much as are to be perceived in the plainsong of the Catholic, the Byzantine, and the Armenian

churches, as well as Hungarian, Roma, Persian and Arab

sources.

CANTORIAL AND SYNAGOGUE MUSIC

appeared cantillation, prayer-motive, xed melody, and

hymn as forms of synagogal music.

2.1 Reminiscences

Melody

of

Gentile

Sacred

The contemporaneous musical fashion of the outer world

has ever found its echo within the walls of the synagogue,

so that in the superstructure added by successive generations of transmitting singers there are always discernible

points of comparison, even of contact, with the style and

structure of each successive era in the musical history

of other religious communions. Attention has frequently

been drawn to the resemblances in manner and even in

some points of detail between the chants of the muezzin

and of the reader of the Qur'an with much of the hazzanut, not alone of the Sephardim, who passed so many

centuries in Arab lands, but also of the Ashkenazim,

equally long located far away in northern Europe.

The intonations of the Sephardim even more intimately

recall the plain-song of the Mozarabian Christians, which

ourished in their proximity until the 13th century. Their

2 Cantorial and synagogue music chants and other set melodies largely consist of very short

phrases often repeated, just as Perso-Arab melody so ofThe traditional mode of singing prayers in the synagogue ten does; and their congregational airs usually preserve a

is often known as hazzanut, the art of being a hazzan Morisco or other Peninsular character.

(cantor)". It is a style of orid melodious intonation which The Cantillation reproduces the tonalities and the

requires the exercise of vocal agility. It was introduced melodic outlines prevalent in the western world during

into Europe in the 7th century, then rapidly developed.

the rst ten centuries of the Diaspora; and the prayerThe age of the various elements in synagogal song may

be traced from the order in which the passages of the

text were rst introduced into the liturgy and were in turn

regarded as so important as to demand special vocalization. This order closely agrees with that in which the successive tones and styles still preserved for these elements

came into use among the Gentile neighbors of the Jews

who utilized them. Earliest of all is the cantillation of

the Scriptures, in which the traditions of the various rites

dier only as much and in the same manner from one another as their particular interpretations according to the

text and occasion dier among themselves. This indeed

was to be anticipated if the dierentiation itself preserves

a peculiarity of the music of the Temple (see Jew. Encyc.

iii. 539a, s.v. Cantillation).

Next comes, from the rst ten centuries, and probably

taking shape only with the Jewish settlement in western

and northern Europe, the cantillation of the Amidah referred to below, which was the rst portion of the liturgy

dedicated to a musical rendering, all that preceded it remaining unchanted . Gradually the song of the precentor commenced at ever earlier points in the service. By

the 10th century, the chant commenced at Barukh SheAmar, the previous custom having been to commence

the singing at Nishmat, these conventions being still

traceable in practise in the introit signalizing the entry

of the junior and of the senior ociant. Hence, in turn,

motives, although their method of employment recalls

far more ancient and more Oriental parallels, are equally

reminiscent of those characteristic of the eighth to the

13th century of the common era. Many of the phrases

introduced in the hazzanut generally, closely resemble

the musical expression of the sequences which developed

in the Catholic Plain-Song after the example set by the

school famous as that of Notker Balbulus, at St. Gall, in

the early 10th century. The earlier formal melodies still

more often are paralleled in the festal intonations of the

monastic precentors of the eleventh to the 15th century,

even as the later synagogal hymns everywhere approximate greatly to the secular music of their day.

The traditional penitential intonation transcribed in the

article Ne'ilah with the piyyut Darkeka closely reproduces the music of a parallel species of medieval Latin

verse, the metrical sequence Missus Gabriel de Clis

by Adam of St. Victor (c. 1150) as given in the Graduale Romanum of Sarum. The mournful chant characteristic of penitential days in all the Jewish rites, is

closely recalled by the Church antiphon in the second

mode Da Pacem Domine in Diebus Nostris (Vesperale

Ratisbon, p. 42). The joyous intonation of the Northern European rite for morning and afternoon prayers

on the Three Festivals (Passover, Sukkot and Shavuot)

closes with the third tone, third ending of the Gregorian

psalmody; and the traditional chant for the Hallel itself,

2.3

Modal Dierence

when not the one reminiscent of the "Tonus Peregrinus, closely corresponds with those for Ps. cxiii. and

cxvii. (Laudate Pueri and Laudate Dominum) in the

"Graduale Romanum" of Ratisbon, for the vespers of

June 24, the festival of John the Baptist, in which evening

service the famous Ut Queant Laxis, from which the

modern scale derived the names of its degrees, also occurs.

3

to such less denite Hebraisms as ne'imah (melody),

shows that the scales and intervals of such prayer-motives

have long been recognized and observed to dier characteristically from those of contemporary Gentile music,

even if the principles underlying their employment have

only quite recently been formulated.

2.3 Modal Dierence

2.2

Prayer-Motives

Next to the passages of Scripture recited in cantillation,

the most ancient and still the most important section of

the Jewish liturgy is the sequence of benedictions which

is known as the Amidah (standing prayer), being the

section which in the ritual of the Dispersion more immediately takes the place of the sacrice oered in the ritual

of the Temple on the corresponding occasion. It accordingly attracts the intonation of the passages which precede and follow it into its own musical rendering. Like

the lessons, it, too, is cantillated. This free intonation

is not, as with the Scriptural texts, designated by any

system of accents, but consists of a melodious development of certain themes or motives traditionally associated

with the individual service, and therefore termed by the

present writer prayer-motives. These are each dierentiated from other prayer-motives much as are the respective forms of the cantillation, the divergence being

especially marked in the tonality due to the modal feeling alluded to above. Tonality depends on that particular position of the semitones or smaller intervals between

two successive degrees of the scale which causes the difference in color familiar to modern ears in the contrast

between major and minor melodies.

Throughout the musical history of the synagogue a particular mode or scale-form has long been traditionally associated with a particular service. It appears in its simplest

form in the prayer-motivewhich is best dened, to use

a musical phrase, as a sort of codato which the benediction (berakha) closing each paragraph of the prayers is

to be chanted. This is associated with a secondary phrase,

somewhat after the tendency which led to the framing of

the binary form in European classical music. The phrases

are amplied and developed according to the length, the

structure, and, above all, the sentiment of the text of the

paragraph, and lead always into the coda in a manner

anticipating the form of instrumental music entitled the

"rondo, although in no sense an imitation of the modern

form. The responses likewise follow the tonality of the

prayer-motive.

This intonation is designated by the Hebrew term nigun

("tune") when its melody is primarily in view, by the

Yiddish term "Shteyger" (scale) when its modal peculiarities and tonality are under consideration, and by the

Romance word gust and the Slavonic skarbowa when

the taste or style of the rendering especially marks it o

from other music. The use of these terms, in addition

The modal dierences are not always so observable in the

Sephardic or Southern tradition. Here the participation

of the congregants has tended to a more general uniformity, and has largely reduced the intonation to a chant

around the dominant, or fth degree of the scale, as if

it were a derivation from the Ashkenazic daily morning

theme (see below), but ending with a descent to the major third, or, less often, to the tonic note. Even where

the particular occasionsuch as a fastmight call for a

change of tonality, the anticipation of the congregational

response brings the close of the benediction back to the

usual major third. But enough dierences remain, especially in the Italian rendering, to show that the principle of

parallel rendering with modal dierence, fully apparent

in their cantillation, underlies the prayer-intonations of

the Sephardim also. This principle has marked eects in

the Ashkenazic or Northern tradition, where it is as clear

in the rendering of the prayers as in that of the Scriptural

lessons, and is also apparent in the erobot.

All the tonalities are distinct. They are formulated in the

subjoined tabular statement, in which the various traditional motives of the Ashkenazic ritual have been brought

to the same pitch of reciting-note in order to facilitate

comparison of their modal dierences.

2.4 Chromatic Intervals

By ancient tradition, from the days when the Jews who

passed the Middle Ages in Teutonic lands were still under the same tonal inuences as the peoples in southeastern Europe and Asia Minor yet are, chromatic scales

(i.e., those showing some successive intervals greater than

two semitones) have been preserved. Sabbath morning

and weekday evening motives are especially aected by

this survival, which also frequently induces the Polish

azzanim to modify similarly the diatonic intervals of

the other prayer-motives. The chromatic intervals survive as a relic of the Oriental tendency to divide an ordinary interval of pitch into subintervals (comp. Hallel

for Tabernacles, the lulab chant), as a result of the intricacy of some of the vocal embroideries in actual employment, which are not infrequently of a character to

daunt an ordinary singer. Even among Western cantors,

trained amid mensurate music on a contrapuntal basis,

there is still a remarkable propensity to introduce the interval of the augmented second, especially between the

third and second degrees of any scale in a descending

SINGING IN THE TEMPLE

cadence. Quite commonly two augmented seconds will

be employed in the octave, as in the frequent form

much loved by Eastern peoplestermed by BourgaultDucoudray (Mlodies Populaires de Grce et d'Orient,

p. 20, Paris, 1876) the Oriental chromatic (see music

below).

Prophets was stimulated by dancing and music (I Sam. x.

5, 10; xix. 20); playing on a harp awoke the inspiration

that came to Elisha (II Kings iii. 15). The description in

Chronicles of the embellishment by David of the Temple

service with a rich musical liturgy represents in essence

the order of the Second Temple, since, as is now generThe harmonia, or manner in which the prayer-motive ally admitted, the liturgical Temple Psalms belong to the

will be amplied into hazzanut, is measured rather by post-exilic period.

the custom of the locality and the powers of the ociant The importance which music attained in the later exilic

than by the importance of the celebration. The precen- period is shown by the fact that in the original writings of

tor will accommodate the motive to the structure of the Ezra and Nehemiah a distinction is still drawn between

sentence he is reciting by the judicious use of the reciting- the singers and the Levites (comp. Ezra ii. 41, 70; vii. 7,

note, varied by melismatic ornament. In the development 24; x. 23; Neh. vii. 44, 73; x. 29, 40; etc.); whereas in

of the subject he is bound to no denite form, rhythm, the parts of the books of Ezra and Nehemiah belonging

manner, or point of detail, but may treat it quite freely to the Chronicles singers are reckoned among the Levites

according to his personal capacity, inclination, and sen- (comp. Ezra iii. 10; Neh. xi. 22; xii. 8, 24, 27; I Chron.

timent, so long only as the conclusion of the passage and vi. 16). In later times singers even received a priestly

the short doxology closing it, if it ends in a benediction, position, since Agrippa II. gave them permission to wear

are chanted to the snatch of melody forming the coda, the white priestly garment (comp. Josephus, Ant. xx.

usually distinctly xed and so furnishing the modal mo- 9, 6). The detailed statements of the Talmud show that

tive. The various sections of the melodious improvisa- the service became ever more richly embellished.

tion will thus lead smoothly back to the original subject,

and so work up to a symmetrical and clear conclusion.

The prayer-motives, being themselves denite in tune and 4 Singing in the Temple

well recognized in tradition, preserve the homogeneity of

the service through the innumerable variations induced by

impulse or intention, by energy or fatigue, by gladness or Unfortunately few denite statements can be made condepression, and by every other mental and physical sensa- cerning the kind and the degree of the artistic develoption of the precentor which can aect his artistic feeling ment of music and psalm-singing. Only so much seems

certain, that the folk-music of older times was replaced by

(see table).

professional music, which was learned by the families of

singers who ociated in the Temple. The participation

of the congregation in the Temple song was limited to certain responses, such as Amen or Halleluiah, or formu3 Occasions for Music

las like Since His mercy endureth forever, etc. As in the

old folk-songs, antiphonal singing, or the singing of choirs

The development of music among the Israelites was coincident with that of poetry, the two being equally an- in response to each other, was a feature of the Temple

cient, since every poem was also sung. Although little service. At the dedication of the walls of Jerusalem, Nemention is made of it, music was used in very early times hemiah formed the Levitical singers into two large choin connection with divine service. Amos vi. 5 and Isa. v. ruses, which, after having marched around the city walls

12 show that the feasts immediately following sacrices in dierent directions, stood opposite each other at the

were very often attended with music, and from Amos v. Temple and sang alternate hymns of praise to God (Neh.

23 it may be gathered that songs had already become a xii. 31). Niebuhr (Reisen, i. 176) calls attention to the

part of the regular service. Moreover, popular festivals fact that in the Orient it is still the custom for a precentor

of all kinds were celebrated with singing and music, usu- to sing one strophe, which is repeated three, four, or ve

ally accompanying dances in which, as a rule, women and tones lower by the other singers. In this connection menmaidens joined. Victorious generals were welcomed with tion may be made of the alternating song of the seraphim

music on their return (Judges xi. 34; I Sam. xviii. 6), and in the Temple, when called upon by Isaiah (comp. Isa.

music naturally accompanied the dances at harvest festi- vi.). The measure must have varied according to the charvals (Judges ix. 27, xxi. 21) and at the accession of kings acter of the song; and it is not improbable that it changed

or their marriages (I Kings i. 40; Ps. xlv. 9). Family fes- even in the same song. Without doubt the striking of the

tivals of dierent kinds were celebrated with music (Gen. cymbals marked the measure.

xxxi. 27; Jer. xxv. 10). I Sam. xvi. 18 indicates that the

shepherd cheered his loneliness with his reed-pipe, and

Lam. v. 14 shows that youths coming together at the

gates entertained one another with stringed instruments.

David by his playing on the harp drove away an evil spirit

from Saul (I Sam. xvi. 16 et seq.); the holy ecstasy of the

Ancient Hebrew music, like much Arabic music today,

was probably monophonic; that is, there is no harmony.

Niebuhr refers to the fact that when Arabs play on different instruments and sing at the same time, almost the

same melody is heard from all, unless one of them sings

or plays as bass one and the same note throughout. It

5.1

Example

was probably the same with the Israelites in olden times,

who attuned the stringed instruments to the voices of the

singers either on the same note or in the octave or at some

other consonant interval. This explains the remark in II

Chron. v. 13 that at the dedication of the Temple the

playing of the instruments, the singing of the Psalms, and

the blare of the trumpets sounded as one sound. Probably the unison of the singing of Psalms was the accord

of two voices an octave apart. This may explain the

terms "'al 'alamot and "'al ha-sheminit. On account of

the important part which women from the earliest times

took in singing, it is comprehensible that the higher pitch

was simply called the maidens key, and ha-sheminit

would then be an octave lower.

There is no question that melodies repeated in each strophe, in the modern manner, were not sung at either the

earlier or the later periods of psalm-singing; since no such

thing as regular strophes occurred in Hebrew poetry. In

fact, in the earlier times there were no strophes at all; and

although they are found later, they are by no means so

regular as in modern poetry. Melody, therefore, must

then have had comparatively great freedom and elasticity and must have been like the Oriental melody of today.

As Niebuhr points out, the melodies are earnest and simple, and the singers must make every word intelligible. A

comparison has often been made with the eight notes of

the Gregorian chant or with the Oriental psalmody introduced into the church of Milan by Ambrosius: the latter,

however, was certainly developed under the inuence of

Grecian music, although in origin it may have had some

connection with the ancient synagogal psalm-singing, as

Delitzsch claims that it was (Psalmen, 3d ed., p. 27).

Contemporary Jewish religious

music

5.1 Example

One type of music, based on Shlomo Carlebachs, is very

popular among Orthodox artists and their listeners. This

type of music usually consists of the same formulaic mix.

This mix is usually brass, horns and strings. These songs

are composed from within one pool of composers and

one pool of arrangers. Many of the entertainers are former yeshiva students, and perform dressed in a dress suit.

Many have day jobs and sideline singing at Jewish weddings. Others moonlight in kollel study or at Jewish organizations. Some have no formal musical education, and

sing mainly pre-arranged songs.

Lyrics are most commonly short passages in Hebrew from

the Torah or the siddur, with the occasional obscure passage from the Talmud. Sometimes there are songs with

lyrics compiled in English in more standard form, with

central themes such as Jerusalem, the Holocaust, Jewish

identity, and the Jewish diaspora.

Some composers are Yossi Green; a big-name arranger

of this type of music is Yisroel Lamm. Artists include Avraham Fried, Dedi Graucher, Lipa Schmeltzer,

Mordechai Ben David, Shloime Dachs, Shloime Gertner,

and Yaakov Shwekey.

5.2 Contemporary Music for Children

Many Orthodox Jews believe that secular music contains messages that are incompatible with Judaism. Parents often limit their childrens exposure to music produced by those other than Orthodox Jews, so that they will

not become negatively inuenced by many of the more,

in the parents eyes, harmful outside ideas and fashions.

A large body of music produced by Orthodox Jews for

children is geared toward teaching religious and ethical

traditions and laws. The lyrics of these songs are generally English with some Hebrew or Yiddish phrases.

Country Yossi, Abie Rotenberg, Uncle Moishy, and the

producers of the 613 Torah Avenue series are examples

of Orthodox Jewish musicians/entertainers whose music

teach children Orthodox traditions.

Main article: Contemporary Jewish religious music

Jewish Music in the 20th century has spanned the gamut

from Shlomo Carlebach's nigunim to Debbie Friedman's

Jewish feminist folk. Velvel Pasternak has spent much

of the late 20th century acting as a preservationist and

committing what had been a strongly oral tradition to paper. John Zorns record label, Tzadik, features a Radical Jewish Culture series that focuses on exploring what

contemporary Jewish music is and what it oers to contemporary Jewish culture.

Periodically Jewish music jumps into mainstream consciousness, Matisyahu (musician) being the most recent

example.

6 References

[1] Mishneh Torah, Hilkoth Ta'niyyoth, Chapter 5, Halakhah 14 (see Touger commentary, footnote 14); Responsa of Maimonides, siman 224 (ed. Blau [Jerusalem,

1960/2014]: vol. 2 p. 399 / vol. 4 [Rubin Mass and

Makhon Moshe, Jerusalem, 2014] p. 137); Rabbi Yosef

Qah's commentary to Mishneh Torah, ibid., in note 27

following his citation of Maimonides responsa, "

( "English: they drink wine with musical instruments,

which alone involves two sins as our master enumerated

above [prohibitions three and four of the ve enumerated in responsum siman 224]). Rabbi Yosef Qahs Col-

10

lected Papers, volume 2,

( Hebrew), page 959: "

, ,

)

(

. English translation Yemenite Jews do not accompany their song with

instrumentseven songs said in houses of feastingdue to

the prohibition of the matter, all the more so their prayers.

Thus Yemenite Jews do not at all recognize song with instruments (that which some villages accompany the songs

of their feasts by tin, I don't know if theres anyone who

would call this a musical instrument), neither percussion

instruments, string instruments, nor wind instruments.

[2] Spielberg Jewish Film Archive - Teiman: The Music of

the Yemenite Jews: 4:324:48: Drumming was used by

all. Mourning the destruction of the second temple resulted in the prohibition of using musical instruments.

The Yemenites, stringent in their observance, accepted

this ban literally. Instead of developing the playing of musical instruments, they perfected singing and rhythm.

Bibliography

Saalschtz, Gesch. und Wrdigung der Musik bei

den Alten Hebrern, 1829;

Delitzsch, Physiologie und Musik, 1868;

Forkel, All-gemeine Gesch. der Musik. i. 173 et seq.

and the bibliography there given.E. G. H.

Jewish Encyclopedia article on MUSIC AND MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS

This article incorporates text from a publication now in

the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901

1906). "article name needed ". Jewish Encyclopedia. New

York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.

Further reading

Idelsohn, A.Z. (1929/1992). Jewish Music, by

A.Z.Idelsohn. New York: Henry Holt and Company/Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-27147-1.

Heskes, Irene (1994). Passport to Jewish Music.

New York: Tara Publications.

External links

A Taste of Jewish Music from the Sephardi World

Yiddish Folk Songs and Tales of Russian Folk

10 See also

Zemirot

Piyyut

Synagogal Music

Gregorian chant

Nigun

SEE ALSO

11

11.1

Text and image sources, contributors, and licenses

Text

History of religious Jewish music Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_religious_Jewish_music?oldid=714513765 Contributors: RK, IZAK, TUF-KAT, LittleDan, Charles Matthews, Hyacinth, Joy, Hadal, Jfdwol, DO'Neil, Falcon Kirtaran, Quadell, Robin klein,

ELApro, Jayjg, Boy in the bands, YUL89YYZ, Johnkarp, Msh210, Alansohn, Sheynhertz-Unbayg, Woohookitty, Georgia guy, Jacobolus,

Commander Keane, Rachack, Ravpapa, Graham87, Deltabeignet, BD2412, Icey, PinchasC, Makaristos, YurikBot, RussBot, Magicmonster, Yoninah, Emersoni, Alex Law, Jkelly, K.Nevelsteen, Aheppenh, SmackBot, David Kernow, Prodego, Hmains, Chabuk, Ekrenor,

Yid613, Can't sleep, clown will eat me, JonHarder, Yokyle, Eliyak, The Box, Eastlaw, ChaimR, Stebbins, Kngrnr, Sirmylesnagopaleentheda, Jessas, JustAGal, WinBot, Gedalia, Darklilac, Storkk, Shaul avrom, TheEditrix2, Hormseld, Scwiers, R'n'B, Dlevinehpc, NewEnglandYankee, Epson291, Leafyplant, Rotter1~enwiki, GuyLumbago, SQL, WRK, Niceguyedc, John J. Bulten, Light show, Jncraton, Gongshow, J04n, Cwunch, Rcsprinter123, Peter Karlsen, ClueBot NG, Helpful Pixie Bot, Symphony117, Jfhutson, Hmainsbot1, Mogism,

Contributor613, BD2412bot and Anonymous: 51

11.2

Images

File:Davids-harp.jpg Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/98/Davids-harp.jpg License: CC BY-SA 2.5 Contributors: No machine-readable source provided. Own work assumed (based on copyright claims). Original artist: No machine-readable author

provided. Amoruso~commonswiki assumed (based on copyright claims).

11.3

Content license

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Guitar For SongwritersDokument209 SeitenGuitar For Songwritersesly100% (3)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Sheet Music Collection For PianoDokument1 SeiteSheet Music Collection For Pianojllassman33% (3)

- Rolling Stone USA - 05 2019 PDFDokument99 SeitenRolling Stone USA - 05 2019 PDFRafisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amazing Grace - Score PDFDokument11 SeitenAmazing Grace - Score PDFPearl PhillipsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harlem RenaissanceDokument37 SeitenHarlem RenaissancegooberdopeNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Aichinger - Stabat MaterDokument3 SeitenAichinger - Stabat MaterDirk MaesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Load and Resistance Factor DesignDokument9 SeitenLoad and Resistance Factor DesignYan Naung Ko100% (2)

- Lecuona Madrigal Sánchez Galarraga VersosDokument1 SeiteLecuona Madrigal Sánchez Galarraga VersosalbertojoyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judith McNaught - BibilografieDokument2 SeitenJudith McNaught - BibilografiePanda EP0% (1)

- Chord Progression LessonDokument4 SeitenChord Progression LessonMonica SanchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCHRP Report 507Dokument87 SeitenNCHRP Report 507Yoshua YangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Instructional Planning DocumentDokument8 SeitenInstructional Planning Documentfedilyn cenabreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consolidation/Remedial Work on Used to-Simple Past-Would Be/Get Used ToDokument3 SeitenConsolidation/Remedial Work on Used to-Simple Past-Would Be/Get Used TokiriakosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1989 1949 OdemarkDokument40 Seiten1989 1949 OdemarkStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epigenetic SDokument6 SeitenEpigenetic SStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mathematical Expression of The CBR RelationsDokument5 SeitenMathematical Expression of The CBR RelationsStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sydney Morning HeraldDokument4 SeitenThe Sydney Morning HeraldStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biology Study Suggests FatherDokument6 SeitenBiology Study Suggests FatherStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Westergaard Solutions PDFDokument11 SeitenWestergaard Solutions PDFStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- BMC Evol BiolDokument17 SeitenBMC Evol BiolStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fulltext PDFDokument263 SeitenFulltext PDFStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture No.2Dokument125 SeitenLecture No.2Roberto TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Is Working Stress Method (ASD) Different From Limit State Method (LRFD or LFD) - Assumptions, Advantages and Comparisons - CivilDigitalDokument4 SeitenHow Is Working Stress Method (ASD) Different From Limit State Method (LRFD or LFD) - Assumptions, Advantages and Comparisons - CivilDigitalStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Deterministic To Probabilistic Way of Thinking in Structural EngineeringDokument5 SeitenFrom Deterministic To Probabilistic Way of Thinking in Structural EngineeringswapnilNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Major Design Philosophies - Working Stress, Ultimate Load and Limit State - CivilDigitalDokument6 Seiten3 Major Design Philosophies - Working Stress, Ultimate Load and Limit State - CivilDigitalStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Downloads Unformal Factores de Carga LRFDDokument5 SeitenDownloads Unformal Factores de Carga LRFDRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Partial Differentiation With Non-Independent VariablesDokument6 SeitenPartial Differentiation With Non-Independent VariablesStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Load and Resistance Factor Design by Theodore V. GalambosDokument34 SeitenLoad and Resistance Factor Design by Theodore V. Galambosrobersasmita100% (1)

- F Selected ProblemsDokument21 SeitenF Selected ProblemsStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pinto Et Al Bene 2011Dokument11 SeitenPinto Et Al Bene 2011Stacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Downloads Unformal Factores de Carga LRFDDokument5 SeitenDownloads Unformal Factores de Carga LRFDRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BDP 1 PDFDokument16 SeitenBDP 1 PDFAnonymous nbqjncpIMNoch keine Bewertungen

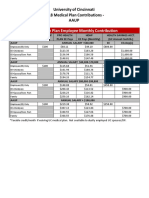

- 2018 Benefit Cost Aaup All FinalDokument2 Seiten2018 Benefit Cost Aaup All FinalStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- c3 GoodnessofFitTestsDokument13 Seitenc3 GoodnessofFitTestsLordRoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Is Working Stress Method (ASD) Different From Limit State Method (LRFD or LFD) - Assumptions, Advantages and Comparisons - CivilDigitalDokument4 SeitenHow Is Working Stress Method (ASD) Different From Limit State Method (LRFD or LFD) - Assumptions, Advantages and Comparisons - CivilDigitalStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statistics Review 7 Correlation and RegressionDokument9 SeitenStatistics Review 7 Correlation and RegressionManish Chandra PrabhakarNoch keine Bewertungen

- FREQUENCY Function - Office SupportDokument5 SeitenFREQUENCY Function - Office SupportStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cal Thomas - Roy Moore, God and The Choice Evangelicals Must Make - Fox NewsDokument2 SeitenCal Thomas - Roy Moore, God and The Choice Evangelicals Must Make - Fox NewsStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Redirecting Error Messages From Command Prompt - STDERR - STDOUTDokument3 SeitenRedirecting Error Messages From Command Prompt - STDERR - STDOUTStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data - Measures-of-Central-Tendency - PDF: The Following Three Problems Were Adapted FromDokument3 SeitenData - Measures-of-Central-Tendency - PDF: The Following Three Problems Were Adapted FromStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hafta 3 Pavement DesignDokument30 SeitenHafta 3 Pavement DesignStacy JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Guide Area of Study 1 (The Piano Music of Chopin Brahms and Grieg)Dokument41 SeitenTeaching Guide Area of Study 1 (The Piano Music of Chopin Brahms and Grieg)Quinton Chu Lok SangNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Hard Days NightDokument3 SeitenA Hard Days NightPetraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 100 CÂU HỎI SỬA LỖI SAIDokument15 Seiten100 CÂU HỎI SỬA LỖI SAILinh KhanhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sarojini Naidu, Saratchandra ChattopadhyayDokument4 SeitenSarojini Naidu, Saratchandra ChattopadhyayTM MediaworksNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2022 Music LibrarianDokument8 Seiten2022 Music LibrarianDavi FrançaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epiphone Sheraton Ii SpecificationsDokument2 SeitenEpiphone Sheraton Ii SpecificationsFederico PratesiNoch keine Bewertungen

- CampfireDokument25 SeitenCampfireDarren SitjarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essays On Art by Clutton-Brock, A. (Arthur), 1868-1924Dokument46 SeitenEssays On Art by Clutton-Brock, A. (Arthur), 1868-1924Gutenberg.orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aptis Listening Practice Materials For Trainersqs2Dokument4 SeitenAptis Listening Practice Materials For Trainersqs2Alejandro Florez50% (2)

- Методичка органDokument274 SeitenМетодичка органOxana BondarevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Be My Vision Chart LyricsDokument1 SeiteBe My Vision Chart LyricsDayra GonzálezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Music Theory Exam Prep GuideDokument3 SeitenMusic Theory Exam Prep GuideTemilade OshoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pirates of The Caribbean ConductorDokument24 SeitenPirates of The Caribbean ConductorCaleb ChongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bach's Influence on Four-Part HarmonyDokument3 SeitenBach's Influence on Four-Part HarmonyFREIMUZIC0% (1)

- INGLÉSDokument2 SeitenINGLÉSLucasNoch keine Bewertungen

- RadiosDokument12 SeitenRadiosAl-Qudsi LViinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Snapple FactsDokument26 SeitenSnapple FactsJessica GoldenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Top Filipino Artists & Music GenresDokument36 SeitenTop Filipino Artists & Music GenresMich MiradaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carulli Ferdinando Andantino en Sol 46977 PDFDokument1 SeiteCarulli Ferdinando Andantino en Sol 46977 PDFClaudia DiazNoch keine Bewertungen