Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

4 Mutuc V Comelec

Hochgeladen von

Alyanna Dia Marie BayaniOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

4 Mutuc V Comelec

Hochgeladen von

Alyanna Dia Marie BayaniCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

228

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

No. L-32717. November 26, 1970.

AMELITO R. MUTUC, petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON

ELECTIONS, respondent.

Statutory Construction; Principle of Ejusdem Generis.

Under the well-known principle of ejusdem generis, the general

words following any enumeration being applicable only to things

of the same kind or class as those specifically referred to. It is

quite apparent that what was contemplated in the Constitutional

Convention Act was the distribution of gadgets of the kind

referred to as a means of inducement to obtain a favorable vote

for the candidate responsible for its distribution.

Same; Cardinal principle of construction.A statute should

be interpreted to assure its being in consonance with, rather than

repugnant to, any constitutional command or prescription. Thus,

certain Administrative Code provisions were given a "construction

which should be more in harmony with the tenets of the

fundamental law." The desirability of remaining in that fashion.

229

VOL. 36, NOVEMBER 26, 1970

229

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

the taint of constitutional infirmity from legislative enactments

has always commended itself. The judiciary may even strain the

ordinary meaning of words to avert any collision between what a

statute provides and what the Constitution requires. The

objective is to reach an interpretation rendering it free from

constitutional defects. To paraphrase Justice Cardozo, if at all

possible, the conclusion reached must avoid not only that it is

unconstitutional, but also grave doubts upon that score.

Constitutional Law; Free Speech.In unequivocal language,

the Constitution prohibits an abridgment of free speech or a free

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

1/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

press. It has been the constant holding that this preferred

freedom calls all the more for the utmost respect when what may

be curtailed is the dissemination of information to make more

meaningful the equally vital right of suffrage. The Commission on

Elections, in prohibiting the use of taped jingle for campaign

purposes did, in effect, impose censorship, an evil against which

this constitutional right is directed. Nor could the Commission

justify its action by the assertion that petitioner, if he would not

resort to taped jingle, would be free, either by himself or through

others, to use his mobile loudspeakers. Precisely, the

constitutional guarantee is not to be emasculated confining it to a

speaker having his say, but not perpetuating what is uttered by

him through tape or other mechanical contrivances.

Same; Obedience to the fundamental law.The concept of the

Constitution as the fundamental law, setting forth the criterion

for the validity of any public act whether proceeding from the

highest official or the lowest functionary, is a postulate of our

system of government. That is to manifest fealty to the rule of

law, with priority accorded to that which occupies the topmost

rung in the legal hierarchy. The three departments of government

in the discharge of the functions with which it is entrusted have

no choice but to yield obedience to its commands. Whatever limits

it imposes must be observed.

Same; Commission on Elections; Power of decision of the

Commission on Elections limited to purely administrative ques-

tions.As a branch of the executive departmentalthough

independent of the Presidentto which the Constitution has

given the "exclusive charge" of the enforcement and

administration of all laws relative to the conduct of elections, the

power of decision of the Commission is limited to purely

"administrative questions." It has been the constant holding, as it

could not have been otherwise, that the Commission cannot

exercise any authority in conflict with or outside of the law, and

there is no higher law than the Constitution.

230

230

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

ORIGINAL PETITION in the Supreme Court. Prohibition.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

Amelito R. Mutuc in his own behalf.

Romulo C. Felizmea for respondent.

FERNANDO, J.:

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

2/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

The invocation of his right to free speech by petitioner

Amelito Mutuc, then a candidate for delegate to the

Constitutional Convention, in this special civil action for

prohibition to assail the validity of a ruling of respondent

Commission on Elections enjoining the use of a taped jingle

for campaign purposes, was not in vain. Nor could it be

considering the conceded absence of any express power

granted to respondent by the Constitutional Convention

Act to so require and the bar to any such implication

arising from any provision found therein, if deference be

paid to the principle that a statute is to be construed

consistently with the fundamental law, which accords the

utmost priority to freedom of expression, much more so

when utilized for electoral purposes. On November 3, 1970,

the very same day the case was orally argued, five days

after its filing, with the election barely a week away, we

issued a minute resolution granting the writ of prohibition

prayed for. This opinion is intended to explain more fully

our decision.

In this special civil action for prohibition filed on

October 29, 1970, petitioner, after setting forth his being a

resident of Arayat, Pampanga, and his candidacy for the

position of delegate to the Constitutional Convention,

alleged that respondent Commission on Elections, by a

telegram sent to him five days previously, informed him

that his certificate of candidacy was given due course but

prohibited him from using jingles in his mobile units

equipped with sound systems and loud speakers, an order

which, according to him, is "violative of [his] constitutional

right

231

VOL. 36, NOVEMBER 26, 1970

231

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

1

* * * to freedom of speech." There being no plain, speedy

and adequate remedy, according to petitioner, he would

seek a writ of prohibition, at the same time praying for a

preliminary injunction. On the very next day, this Court

adopted a resolution requiring respondent Commission on

Elections to file an answer not later than November 2,

1970, at the same time setting the case for hearing for

Tuesday November 3, 1970. No preliminary injunction was

issued. There was no denial in the answer filed by

respondent on November 2, 1970, of the factual allegations

set forth in the petition, but the justification for the

prohibition was premised on a provision of the

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

3/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

2

Constitutional Convention Act, which made it unlawful for

candidates "to purchase, produce, request or distribute

sample ballots, or electoral propaganda gadgets such as

pens, lighters, fans (of whatever nature), flashlights,

athletic goods or materials, wallets, bandanas, shirts, hats,

matches, cigarettes,

and the like, whether of domestic or

3

foreign origin." It was its contention that the jingle

proposed to be used by petitioner is the recorded or taped

voice of a singer and therefore a tangible propaganda

material, under the above statute subject to confiscation. It

prayed that the petition be denied for lack of merit. The

case was argued, on November 3, 1970, with petitioner

appearing in his behalf and Attorney Romulo C. Felizmea

arguing in behalf of respondent.

This Court, after deliberation and taking into account

the need for urgency, the election being barely a week

away, issued on the afternoon of the same day, a minute

resolution granting the writ of prohibition, setting forth the

absence of statutory authority on the part of respondent to

impose such a ban in the light of the doctrine of ejusdem

generis as well as the principle that the construction placed

on the statute by respondent Commission on Elections

would raise serious doubts about its validity, considering

the infringement of the right of free speech

_______________

1

Petition, paragraphs 1 to 5.

Republic Act No. 6132 (1970).

Section 12 (E), Ibid.

232

232

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

cordingly, as prayed for, respondent Commission on

Elections is permanently restrained and prohibited from

enforcing or implementing or demanding compliance with

its aforesaid order banning the use of political jingles

by

4

candidates. This resolution is immediately executory."

1. As made clear in our resolution of November 3, 1970,

the question before us was one of power. Respondent

Commission on Elections was called upon to justify such a

prohibition imposed on petitioner. To repeat, no such

authority was granted by the Constitutional Convention

Act. It did contend, however, that one of its provisions

referred to above makes unlawful the distribution of

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

4/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

electoral propaganda gadgets, mention being made of pens,

lighters, fans, flashlights, athletic goods or materials,

wallets, bandanas, shirts, hats, matches, and cigarettes,

5

and concluding with the words "and the like." For

respondent Commission, the last three words sufficed to

justify such an order. We view the matter differently. What

was done cannot merit our approval under the well-known

principle of ejusdem generis, the general words following

any enumeration being applicable only to things of

the

6

same kind or class as those specifically referred to. It is

quite apparent that what was contemplated in the Act was

the distribution of gadgets of the kind referred to as a

means of inducement to obtain a favorable vote for the

candidate responsible for its distribution.

The more serious objection, however, to the ruling of

respondent Commission was its failure to manifest fealty to

a cardinal principle of construction that a statute should be

interpreted to assure its being in consonance with, rather

_______________

4

Resolution of Nov. 3, 1970.

Section 12(E), Constitutional Convention Act.

Cf. United States v. Santo Nio, 13 Phil. 141 (1909); Go Tiaoco y

Hermanos v. Union Insurance Society of Canton, 40 Phil. 40 (1919);

People vs. Kottinger, 45 Phil. 352 (1923); Cornejo v. Naval, 54 Phil. 809

(1930); Ollada v. Court of Tax Appeals, 99 Phil. 605 (1956); Roman

Catholic Archbishop of Manila v. Social Security Commission, L-15045,

Jan. 20, 1961, 1 SCRA 10.

233

VOL. 36, NOVEMBER 26, 1970

233

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

than repugnant

to, any constitutional command or

7

prescription. Thus, certain Administrative Code provisions

were given a "construction which should be more

in

8

harmony with the tenets of the fundamental law." The

desirability of removing in that fashion the taint of

constitutional infirmity from legislative enactments has

always commended itself. The judiciary may even strain

the ordinary meaning of words to avert any collision

between what a statute provides and what the Constitution

requires. The objective is to reach an interpretation

rendering it free from constitutional defects. To paraphrase

Justice Cardozo, if at all possible, the conclusion reached

must avoid not only that it is unconstitutional, but also

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

5/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

9

grave doubts upon that score.

2. Petitioner's submission of his side of the controversy,

then, has in its favor obeisance to such a cardinal precept.

The view advanced by him that if the above provision of the

Constitutional Convention Act were to lend itself to the

view that the use of the taped jingle could be prohibited,

then the challenge of unconstitutionality would be difficult

to meet. For, in unequivocal language, the Constitution

prohibits an abridgment of free speech or a free press. It

has been our constant holding that this preferred freedom

calls all the more for the utmost respect when what may be

curtailed is the dissemination of information to

_______________

7

Cf. Herras Teehankee v. Rovira, 75 Phil. 634 (1945); Manila Electric

Co. v. Public Utilities Employees Association, 79 Phil. 409 (1947); Araneta

v. Dinglasan, 84 Phil. 368 (1949); Guido v. Rural Progress Administration,

84 Phil. 847 (1949); City of Manila v. Arellano Law Colleges, 85 Phil. 663

(1950); Ongsiako v. Gamboa, 86 Phil. 50 (1950); Radiowealth v. Agregado,

86 Phil. 429 (1950); Sanchez v. Harry Lyons Construction, Inc., 87 Phil.

532 (1950); American Bible Society v. City of Manila, 101 Phil. 386 (1957);

Gonzales v. Hechanova, L-21897, Oct. 22, 1963, 9 SCRA 230; Automotive

Parts and Equipment Co., Inc. v. Lingad, L-26406, Oct. 31, 1969, 30 SCRA

248; J. M. Tuason and Co., Inc. v. Land Tenure Administration, L-21064,

Feb. 18, 1970, 31 SCRA 413.

8

Radiowealth v. Agregado, 86 Phil. 429 (1950).

Moore Ice Cream Co. v. Ross, 289 US 373 (1933).

234

234

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

make more meaningful the equally vital right of suffrage.

What respondent Commission did, in effect, was to impose

censorship on petitioner, an evil against which this

constitutional right is directed. Nor could respondent

Commission justify its action by the assertion that

petitioner, if he would not resort to taped jingle, would be

free, either by himself or through others, to use his mobile

loudspeakers. Precisely, the constitutional guarantee is not

to be emasculated by confining it to a speaker having his

say, but not perpetuating what is uttered by him through

tape or other mechanical contrivances. If this Court were to

sustain respondent Commission, then the effect would

hardly be distinguishable from a previous restraint. That

cannot be validly done. It would negate indirectly what the

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

6/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

10

Constitution in express terms assures.

3. Nor is this all. The concept of the Constitution as the

fundamental law, setting forth the criterion for the validity

of any public act whether proceeding from the highest

official or the lowest functionary, is a postulate of our

system of government. That is to manifest fealty to the rule

of law, with priority accorded to that which occupies the

topmost rung in the legal hierarchy. The three

departments of government in the discharge of the

functions with which it is entrusted have no choice but to

yield obedience to its commands. Whatever limits it

imposes must be observed. Congress in the enactment of

statutes must ever be on guard lest the restrictions on its

authority, whether substantive or formal, be transcended.

The Presidency in the execution of the laws cannot ignore

or disregard what it ordains. In its task of applying the law

to the facts as found in deciding cases, the judiciary is

called upon to maintain inviolate what is decreed by the

fundamental law. Even its power of judicial review to pass

upon the validity of the acts of the coordinate branches in

the course of adjudication is a logical corollary of this basic

principle that the Constitution is paramount. It overrides

any governmental measure that fails to live up to its man-

_______________

10

Cf. Saia v. People of the State of New York, 334 US 558 (1948).

235

VOL. 36, NOVEMBER 26, 1970

235

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

dates. Thereby there is a recognition of its being the

supreme law.

To be more specific, the competence entrusted to

respondent Commission was aptly summed up by the

present Chief Justice thus: "Lastly, as the branch of the

executive departmentalthough independent of the

Presidentto which the Constitution has given the

'exclusive charge' of the 'enforcement and administration of

all laws relative to the conduct of elections,' the power of

decision of the Commission

is limited to purely

11

'administrative questions.'"

_______________

11

Abcede v. Hon. Imperial, 103 Phil. 136 (1958). The portion of the

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

7/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

opinion from which the above excerpt is taken reads in full: 'Lastly, as the

branch of the executive departmentalthough independent of the

Presidentto which the Constitution has given the 'exclusive charge' of

the 'enforcement and administration of all laws relative to the conduct of

elections,' the power of decision of the Commission is limited to purely

'administrative questions.' (Article X, sec. 2, Constitution of the

Philippines) It has no authority to decide matters 'involving the right to

vote.' It may not even pass upon the legality of a given vote (Nacionalista

Party v. Commission on Elections, 47 Off. Gaz., [6], 2851). We do not see,

therefore, how it could assert the greater and more far-reaching authority

to determine whoamong those possessing the qualifications prescribed

by the Constitution, who have complied with the procedural requirements,

relative to the filing of certificate of candidacyshould be allowed to enjoy

the full benefits intended by law therefore. The question whether in order

to enjoy those benefitsa candidate must be capable of 'understanding

the full meaning of his acts and the true significance of election,' and must

haveover a month prior to the elections (when the resolution complained

of was issued) 'the tiniest chance to obtain the favorable indorsement of a

substantial portion of the electorate, is a matter of policy, not of

administration and enforcement of the law which policy must be

determined by Congress in the exercise of its legislative functions. Apart

from the absence of specific statutory grant of such general, broad power

as the Commission claims to have, it is dubious whether, if so grantedin

the vague, abstract, indeterminate and undefined manner necessary in

order that it could pass upon the factors relied upon in said resolution

(and such grant must not be deemed made, in the absence of clear and

positive provision to such effect, which is absent in the case at bar)the

legislative enactment would not amount to undue delegation of legislative

power. (Schechter vs. U.S., 295 US 495, 79 L. ed. 1570.)" pp. 141-142.

236

236

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

It has been the constant holding of this Court, as it could

not have been otherwise, that respondent Commission

cannot exercise any authority in conflict with or outside of

12

the law, and there is no higher law than the Constitution.

Our decisions which liberally construe its powers are

precisely inspired by the thought that only thus may its

responsibility under the Constitution to insure

free, orderly

13

and honest elections be adequately fulfilled. There could

be no justification then for lending approval to any ruling

or order issuing from respondent Commission, the effect of

which would be to nullify so vital a constitutional right as

free speech. Petitioner's case, as was obvious from the time

of its filing, stood on solid footing.

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

8/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

WHEREFORE, as set forth in our resolution of

November 3, 1970, respondent Commission is permanently

restrained and prohibited from enforcing or implementing

_______________

12

Cf. Cortez v. Commission on Elections, 79 Phil. 352 (1947);

Nacionalista Party v. Commission on Elections, 85 Phil. 149 (1949) ;

Guevara v. Commission on Elections, 104 Phil. 268 (1958); Masangcay v.

Commission on Elections, L-13827, Sept. 28, 1962, 6 SCRA 27; Lawsin v.

Escalona, L-22540, July 31, 1964, 11 SCRA 643; Ututalum v. Commission

on Elections, L-25349, Dec. 3, 1965, 15 SCRA 465; Janairo v. Commission

on Elections, L-28315, Dec. 8, 1967, 21 SCRA 1173; Abes v. Commission

on Elections, L-28348, Dec. 15, 1967, 21 SCRA 1252; Ibuna v. Commission

on Elections, L-28328, Dec. 29, 1967, 21 SCRA 1457; Binging Ho v. Mun.

Board of Canvassers, L-29051, July 28, 1969, 28 SCRA 829.

13

Cf. Cauton v. Commission on Elections, L-25467, April 27, 1967, 19

SCRA 911. The other cases are Espino v. Zaldivar, L-22325, Dec. 11, 1967,

21 SCRA 1204; Ong v. Commission on Elections, L-28415, Jan. 29, 1968,

22 SCRA 241; Mutuc v. Commission on Elections, L-28517, Feb. 21, 1968,

22 SCRA 662; Pedido v. Commission on Elections, L-28539, March 30,

1968, 22 SCRA 1403; Aguam v. Commission on Elections, L-28955, May

28, 1968, 23 SCRA 883; Pelayo, Jr. v. Commission on Elections, L-28869,

June 29, 1968, 23 SCRA 1374; Pacis v. Commission on Elections, L-29026,

Sept. 28, 1968, 25 SCRA 377; Ligot v. Commission on Elections, L-31380,

Jan. 21, 1970, 31 SCRA 45; Abrigo v. Commission on Elections, L-31374,

Jan. 21, 1970, 31 SCRA 27; Moore v. Commission on Elections, L-31394,

Jan. 23, 1970, 31 SCRA 60; Ilarde v. Commission on Elections, L-31446,

Jan. 23, 1970, 31 SCRA 72; Sinsuat v. Pendatun, L-31501, June 30, 1970,

33 SCRA 630.

237

VOL. 36, NOVEMBER 26, 1970

237

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

or demanding compliance with its aforesaid order banning

the use of political taped jingles. Without pronouncement

as to costs.

Concepcion, C.J., Reyes, J.B.L., Makalintal,

Zaldivar, Castro, Barredo and Villamor, JJ., concur.

Dizon and Makasiar, JJ., are on official leave.

Teehankee, J., concurs in a separate opinion.

Writ granted.

TEEHANKEE, J., concurring:

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

9/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

1

In line with my separate opinion in Badoy vs. Ferrer on the

unconstitutionality of the challenged provisions of the 1971

Constitutional Convention Act, I concur with the views of

Mr. Justice Fernando in the main opinion that "there could

be no justification . . . . for lending approval to any ruling or

order issuing from respondent Commission, the effect of

which would be to nullify so vital a constitutional right as

free speech." I would only add the following observations:

This case once again calls for application of the

constitutional test of reasonableness required by the due

process clause of our Constitution, Originally, respondent

Commission in its guidelines prescribed summarily that

the use by a candidate of a "mobile unitroaming around

and announcing a meeting and the name of the candidate .

. . is prohibited. If it is used only for a certain place for a

meeting and he uses his

sound system at the meeting itself,

2

there is no violation." Acting upon petitioner's application,

however, respondent Commission ruled that "the use of a

sound system by anyone be he a candidate or not whether

stationary or part of a mobile unit is not prohibited by the

1971 Constitutional Convention Act" but imposed the

condition"provided that there are no jingles and no

streamers or posters placed in carriers."

_______________

1

L-32546 & 32551, Oct. 17, 1970, re: sections 8(A) and 12 (F) and other

related provisions.

2

Petition, page 9.

238

238

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

Respondent Commission's narrow view is that "the use of a

'jingle,' a verbally recorded form of election propaganda, is

no different from the use of a 'streamer' or 'poster,' a

printed form of election propaganda, and both forms of

election advertisement fall under the prohibition contained

in sec. 12 of R.A. 6132," and "the record disc or tape where

said 'jingle' has been recorded can be subject of confiscation

by the respondent Commission under par. (E) of sec. 12 of

R.A. 6132." In this modern day and age of the electronically

recorded or taped voice which may be easily and

inexpensively disseminated through a mobile sound system

throughout

the

candidate's

district,

respondent

Commission would outlaw "recorded or taped voices" and

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

10/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

would exact of the candidate that he make use of the

mobile sound system only by personal transmission and

repeatedly personally sing his "jingle" or deliver his spoken

message to the voters even if he loses his voice in the

process or employ another person to do so personally even if

this should prove more expensive and less effective than

using a recorded or taped voice.

Respondent Commission's strictures clearly violate,

therefore, petitioner's basic freedom of speech and

expression. They cannot pass the constitutional test of

reasonableness in that they go far beyond a reasonable

relation to the proper governmental object and are

manifestly unreasonable, oppressive and arbitrary.

Insofar as the placing of the candidate's "streamers" or

posters on the mobile unit or carrier is concerned,

respondent Commission's adverse ruling that the same

falls within the prohibition of section 12, paragraphs (C)

and (E) has not been appealed by petitioner. I would note

that respondent Commission's premise that "the use of a

'jingle' ... is no different from the use of a 'streamer' or

'poster' "in that these both represent forms of election

advertisementsto make the candidate and the fact of his

candidacy known to the votersis correct, but its

conclusion is not. The campaign appeal of the "jingle" is

through the voters' ears while that of the "streamers" is

through the voters' eyes. But if it be held that the

Commission's ban

239

VOL. 36, NOVEMBER 26, 1970

239

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

on "jingles" abridges unreasonably, oppressively and

arbitrarily the candidate's right of free expression, even

though such "jingles" may occasionally offend some

sensitive ears, the Commission's ban on "streamers" being

placed on the candidate's mobile unit or carrier, which

"streamers" are less likely to offend the voters' sense of

sight should likewise be held to be an unreasonable,

oppressive and arbitrary curtailment of the candidate's

same constitutional right.

The intent of the law to minimize election expenses as

invoked by respondent Commission, laudable as it may be,

should not be sought at the cost of the candidate's

constitutional rights in the earnest pursuit of his

candidacy, but is to be fulfilled in the strict and effective

implementation of the Act's limitation in section 12(G) on

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

11/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

the total expenditures that may be made by a candidate or

by another person with his knowledge and consent.

Notes.(a) Ejusdem generis doctrine.Where a statute

describes things of a particular class or kind, accompanied

by words of generic character preceded by the word "other,"

the generic words will usually be limited to things of a

kindred nature with those particularly enumerated, unless

there is something in the context or history of the statute to

repeal such inference (Murphy, Morris & Co. vs. Collector

of Customs, 11 Phil. 456). This rule, known as the doctrine

of ejusdem generis, also holds true where the term

"otherwise" is used in a statute, as, for example in Section

30 (d) (2) of the National Internal Revenue Code dealing

with corporate losses "not compensated for by insurance or

otherwise" (Cu Unjieng Sons, Inc. vs. Board of Tax Appeals,

L-6296, Sept. 29, 1956). See also Go Tiaoco y Hermanos vs.

Union Insurance Society of Canton, 40 Phil. 40.

This rule has not only been applied to statutes. It has

also been applied to contracts. Thus, in Director of Public

Works vs. Sing Juco, 53 Phil. 205, it was held that where a

power of attorney is executed primarily to enable an

240

240

SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED

Mutuc vs. Commission on Elections

attorney-in-fact, as manager of a business, to conduct its

affairs for the owner or principal, and the attorney-infact is

authorized to execute contracts relating to the principals'

property, such power will not be interpreted as power to

bind the principal by a contract of independent guaranty,

one not connected with the mercantile business. According

to the Court in that case, general words cannot extend the

power to making a contract of guaranty, but will be limited

by the rule of ejusdem generis to matters similar to those

mentioned.

But the doctrine of ejusdem generis is but a rule of

construction adopted as an aid to ascertain and give effect

to the legislative intent when that intent is uncertain and

ambiguous. The same should not, therefore, be given such

wide application that would operate to defeat the purpose

of the law. In other words, the doctrine is not of universal

application. Its application must yield to the manifest

intent of Congress (Genato Commercial Corporation vs.

Court of Tax Appeals, L-11727, Sept. 29, 1958). It does not

apply where, on consideration of the whole law on the

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

12/13

8/28/2014

CentralBooks:Reader

subject and the purpose sought, it appears that the

legislature intended the general words to go beyond the

class specifically designated (City of Manila vs. Lyric Music

House, Inc., 62 Phil. 125). In other words, if the intent of

the law appears clearly from other parts to be contrary to

the result which would be reached by the application of the

rule of ejusdem generis, said rule must give way (U.S. vs.

Santo Nio, 13 Phil. 141).

(b) Rule when there is conflict between statute and rule or

regulation implementing it.In case of discrepancy

between the basic Act and the rule or regulation issued to

implement it, the former shall prevail, for the reason that

the rule issued to implement a law cannot go beyond the

terms and provisions of the latter (People vs. Lim, L-14432,

July 26, 1960).

241

Copyright 2014 Central Book Supply, Inc. All rights reserved.

http://www.central.com.ph/sfsreader/session/000001481ce75dc4ee3a76e6000a0082004500cc/t/?o=False

13/13

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Address at Oregon Bar Association annual meetingVon EverandAddress at Oregon Bar Association annual meetingNoch keine Bewertungen

- First DivisionDokument5 SeitenFirst Divisionmee tooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc vs. COMELECDokument3 SeitenMutuc vs. COMELECRichard Irish AcainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc Vs ComelecDokument4 SeitenMutuc Vs ComelecLelouch LamperNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc Vs Comelec, 36 Scra 228Dokument3 SeitenMutuc Vs Comelec, 36 Scra 228Abhor TyrannyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 96 LapiraDokument5 Seiten96 LapiraPrieti HoomanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc v. COMELECDokument6 SeitenMutuc v. COMELECBianca BNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15.mutuc v. Commission On Elections20210424-12-1usxbe7Dokument7 Seiten15.mutuc v. Commission On Elections20210424-12-1usxbe7Stephanie CONCHANoch keine Bewertungen

- 7f - Mutuc V ComelecDokument4 Seiten7f - Mutuc V ComelecRei TongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc Vs Comelec, GR No. L-32717Dokument9 SeitenMutuc Vs Comelec, GR No. L-32717AddAllNoch keine Bewertungen

- GR L-32717Dokument9 SeitenGR L-32717AM CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- GR L-32717 PDFDokument9 SeitenGR L-32717 PDFAM CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutoc G.R. No. L-32717Dokument6 SeitenMutoc G.R. No. L-32717Fritzie Liza MacapanasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc VS ComelecDokument8 SeitenMutuc VS ComelecSapphireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stat ConDokument12 SeitenStat ConDreamCatcherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc v. ComelecDokument1 SeiteMutuc v. ComelecMaricel SorianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondent Amelito R. Mutuc Romulo C. FelizmeñaDokument6 SeitenPetitioner vs. vs. Respondent Amelito R. Mutuc Romulo C. FelizmeñaSarah C.Noch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. L-32717Dokument1 SeiteG.R. No. L-32717Marianne CristalNoch keine Bewertungen

- (G.R. No. L-32717, November 26, 1970)Dokument4 Seiten(G.R. No. L-32717, November 26, 1970)rommel alimagnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 42 - Fulltext - New York Times Co. v. United States - 403 Us 713Dokument4 Seiten42 - Fulltext - New York Times Co. v. United States - 403 Us 713Wed CornelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc Vs COMELEC 36 SCRA 228Dokument6 SeitenMutuc Vs COMELEC 36 SCRA 228joshemmancarinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amelito R. Mutuc v. Comelec - GR No. L-32717Dokument7 SeitenAmelito R. Mutuc v. Comelec - GR No. L-32717jake31Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc Vs COMELEC 36 SCRA 228Dokument5 SeitenMutuc Vs COMELEC 36 SCRA 228Maria Aerial AbawagNoch keine Bewertungen

- (2-2) Mutuc vs. ComelecDokument2 Seiten(2-2) Mutuc vs. Comelecemmaniago08Noch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court: Amelito R. Mutuc in His Own Behalf. Romulo C. Felizmena For RespondentDokument7 SeitenSupreme Court: Amelito R. Mutuc in His Own Behalf. Romulo C. Felizmena For RespondentVivian Escoto de BelenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc v. Comelec G.R. No. L-32717 November 26, 1970-DigestDokument2 SeitenMutuc v. Comelec G.R. No. L-32717 November 26, 1970-DigestmarkNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. L-32717 Mutuc V COMELEC LawPhilDokument4 SeitenG.R. No. L-32717 Mutuc V COMELEC LawPhilNea TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc Vs ComelecDokument2 SeitenMutuc Vs ComelecJomar Teneza100% (2)

- Comelec Vs MutucDokument1 SeiteComelec Vs MutucAronJamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- WON The Prohibition On Use of Taped Electoral Jingles Violates The Right To Free Speech. YESDokument1 SeiteWON The Prohibition On Use of Taped Electoral Jingles Violates The Right To Free Speech. YESRency CorrigeNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. L-32717. November 26, 1970 DigestDokument2 SeitenG.R. No. L-32717. November 26, 1970 DigestMaritoni RoxasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc v. COMELEC - Case DigestDokument1 SeiteMutuc v. COMELEC - Case DigestFatimah Sahara BalindongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc vs. Commission On ElectionsDokument15 SeitenMutuc vs. Commission On ElectionsJayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc v. ComelecDokument2 SeitenMutuc v. ComelecBelle CabalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bracket 1 CasesDokument91 SeitenBracket 1 CasesAngeline LimpiadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. L-32717 November 26, 1970 AMELITO R. MUTUC, Petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, RespondentDokument2 SeitenG.R. No. L-32717 November 26, 1970 AMELITO R. MUTUC, Petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, RespondentIra Francia AlcazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case 8 in Re: Cunanan, 94 Phil. 534 (1954) FactsDokument9 SeitenCase 8 in Re: Cunanan, 94 Phil. 534 (1954) FactsAshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Construction/Limitations, Section 3 of The COMELEC Rules of ProcedureDokument9 SeitenConstruction/Limitations, Section 3 of The COMELEC Rules of ProcedureRaymund Christian Ong AbrantesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc vs. Comelec 36 Scra 228 1970 (Digest)Dokument1 SeiteMutuc vs. Comelec 36 Scra 228 1970 (Digest)Monica FerilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Primer Election LawDokument23 SeitenPrimer Election LawYour Public ProfileNoch keine Bewertungen

- PLJ Volume 46 Number 2 - 02 - Merlin M. Magallona - Political Law Part TwoDokument23 SeitenPLJ Volume 46 Number 2 - 02 - Merlin M. Magallona - Political Law Part TwoNico RecintoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic Act No. 6735: An Act Providing For A System of Initiative and Referendum and Appropriating Funds ThereforDokument30 SeitenRepublic Act No. 6735: An Act Providing For A System of Initiative and Referendum and Appropriating Funds ThereforUrsulaine Grace FelicianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constituonal Law 1 Midterm ExaminationDokument14 SeitenConstituonal Law 1 Midterm ExaminationVj McNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests Political Law: Defensor-Santiago vs. Guingona G.R. No. 134577, November 18, 1998Dokument6 SeitenCase Digests Political Law: Defensor-Santiago vs. Guingona G.R. No. 134577, November 18, 1998Xyza Faye ForondaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Consti DigestsDokument4 Seiten4 Consti DigestsCai CarpioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Facts:: SyllabusDokument8 SeitenFacts:: Syllabuseinel dcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases Series No. 1Dokument41 SeitenCases Series No. 1Claudine SumalinogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mutuc V COMELEC, GR No L-32717, November 26, 1970Dokument3 SeitenMutuc V COMELEC, GR No L-32717, November 26, 1970Samuel John CahimatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decision (En Banc) Laurel, J.: I. The Facts: (The Court DENIED The Petition.)Dokument38 SeitenDecision (En Banc) Laurel, J.: I. The Facts: (The Court DENIED The Petition.)Neil Angelo Pamfilo RodilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ejusdem GenerisDokument19 SeitenEjusdem GenerisMc Vharn CatreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digested Cases StatDokument6 SeitenDigested Cases StatKristine Dianne CaballaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gonzales v. COMELEC, GR L-28196 & L-28224, Nov. 09, 1967Dokument26 SeitenGonzales v. COMELEC, GR L-28196 & L-28224, Nov. 09, 1967Tin SagmonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adiong vs. ComelecDokument2 SeitenAdiong vs. ComelecMaricel SorianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Francisco Vs HouseDokument28 SeitenFrancisco Vs HouseJu LanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest 2Dokument3 SeitenCase Digest 2Mae VincentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freedom of ExpressionDokument14 SeitenFreedom of ExpressionLeslie Ann LaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondents Villarama & Cruz Marciano LL Aparte, JRDokument13 SeitenPetitioners vs. vs. Respondents Villarama & Cruz Marciano LL Aparte, JRMlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ruling On Access To Trump ArraignmentDokument6 SeitenRuling On Access To Trump ArraignmentToronto StarNoch keine Bewertungen

- AQUINODokument2 SeitenAQUINOMark Joseph DelimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manila Electric Co Vs Pasay TransDokument1 SeiteManila Electric Co Vs Pasay TransAlyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zoreta vs. SimplicianoDokument15 SeitenZoreta vs. SimplicianoAlyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- In The Matter (Feb 8, 2011)Dokument70 SeitenIn The Matter (Feb 8, 2011)Alyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deles vs. Aragona PDFDokument14 SeitenDeles vs. Aragona PDFAlyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blanza vs. ArcangelDokument6 SeitenBlanza vs. ArcangelAlyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cojuangco JR Vs Sandiganbayan: 134307: December 21, 1998: J. Quisumbing: First Division PDFDokument15 SeitenCojuangco JR Vs Sandiganbayan: 134307: December 21, 1998: J. Quisumbing: First Division PDFAlyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- De Leon vs. SalvadorDokument9 SeitenDe Leon vs. SalvadorAlyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catungal Vs RodriguezDokument19 SeitenCatungal Vs RodriguezAlyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- 18 Ibanez de Aldecoa V HSBCDokument27 Seiten18 Ibanez de Aldecoa V HSBCAlyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tolentino vs. Secretary of FinanceDokument45 SeitenTolentino vs. Secretary of FinanceAlyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1-Small Landowners Assoc Vs SARDokument29 Seiten1-Small Landowners Assoc Vs SARAlyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yap Tua Vs Yap CA Kuan and Yap CA KuanDokument3 SeitenYap Tua Vs Yap CA Kuan and Yap CA KuanAlyanna Dia Marie BayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clado-Reyes V LimpeDokument2 SeitenClado-Reyes V LimpeJL A H-DimaculanganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Macroeconomics Adel LauretoDokument66 SeitenMacroeconomics Adel Lauretomercy5sacrizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Account Statement 010721 210122Dokument30 SeitenAccount Statement 010721 210122PhanindraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Compromise AgreementDokument3 SeitenSample Compromise AgreementBa NognogNoch keine Bewertungen

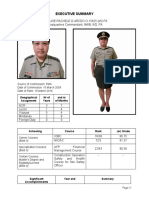

- Executive Summary: Source of Commission: PMA Date of Commission: 16 March 2009 Date of Rank: 16 March 2016Dokument3 SeitenExecutive Summary: Source of Commission: PMA Date of Commission: 16 March 2009 Date of Rank: 16 March 2016Yanna PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vehicle Lease Agreement TEMPLATEDokument5 SeitenVehicle Lease Agreement TEMPLATEyassercarloman100% (1)

- Dawes and Homestead Act Webquest 2017Dokument4 SeitenDawes and Homestead Act Webquest 2017api-262890296Noch keine Bewertungen

- Panay Autobus v. Public Service Commission (1933)Dokument2 SeitenPanay Autobus v. Public Service Commission (1933)xxxaaxxxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bulletin: The Institute of Cost Accountants of IndiaDokument40 SeitenBulletin: The Institute of Cost Accountants of IndiaABC 123Noch keine Bewertungen

- ISLAMIC MISREPRESENTATION - Draft CheckedDokument19 SeitenISLAMIC MISREPRESENTATION - Draft CheckedNajmi NasirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Slave Ship JesusDokument8 SeitenSlave Ship Jesusj1ford2002Noch keine Bewertungen

- VOLIITSPart IDokument271 SeitenVOLIITSPart IrkprasadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tumang V LaguioDokument2 SeitenTumang V LaguioKarez MartinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Busines EthicsDokument253 SeitenBusines Ethicssam.geneneNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Following Payments and Receipts Are Related To Land Land 115625Dokument1 SeiteThe Following Payments and Receipts Are Related To Land Land 115625M Bilal SaleemNoch keine Bewertungen

- CTA CasesDokument177 SeitenCTA CasesJade Palace TribezNoch keine Bewertungen

- TAX (2 of 2) Preweek B94 - Questionnaire - Solutions PDFDokument25 SeitenTAX (2 of 2) Preweek B94 - Questionnaire - Solutions PDFSilver LilyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 08 Albay Electric Cooperative Inc Vs MartinezDokument6 Seiten08 Albay Electric Cooperative Inc Vs MartinezEYNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0452 s03 Ms 2Dokument6 Seiten0452 s03 Ms 2lie chingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Airworthiness Directive: Design Approval Holder's Name: Type/Model Designation(s)Dokument2 SeitenAirworthiness Directive: Design Approval Holder's Name: Type/Model Designation(s)sagarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Misamis Oriental Association of Coco Traders, Inc. vs. Department of Finance SecretaryDokument10 SeitenMisamis Oriental Association of Coco Traders, Inc. vs. Department of Finance SecretaryXtine CampuPotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deutsche Bank, Insider Trading Watermark)Dokument80 SeitenDeutsche Bank, Insider Trading Watermark)info707100% (1)

- M-K-I-, AXXX XXX 691 (BIA March 9, 2017)Dokument43 SeitenM-K-I-, AXXX XXX 691 (BIA March 9, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (2)

- Vice President Security Lending in NYC NY NJ Resume Fernando RiveraDokument3 SeitenVice President Security Lending in NYC NY NJ Resume Fernando Riverafernandorivera1Noch keine Bewertungen

- GR 220835 CIR vs. Systems TechnologyDokument2 SeitenGR 220835 CIR vs. Systems TechnologyJoshua Erik Madria100% (1)

- IMO Online. AdvtDokument4 SeitenIMO Online. AdvtIndiaresultNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Exceedance To AWWA Standards Before It IsDokument2 SeitenIn Exceedance To AWWA Standards Before It IsNBC 10 WJARNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Tallest Buildings in Delhi - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokument13 SeitenList of Tallest Buildings in Delhi - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaSandeep MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article 62 of The Limitation ActDokument1 SeiteArticle 62 of The Limitation ActGirish KallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lledo V Lledo PDFDokument5 SeitenLledo V Lledo PDFJanica DivinagraciaNoch keine Bewertungen