Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

(Journal) J. Barton Cunningham and Ted Eberle - A Guide To Job Enrichment and Redesign PDF

Hochgeladen von

AzwinOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

(Journal) J. Barton Cunningham and Ted Eberle - A Guide To Job Enrichment and Redesign PDF

Hochgeladen von

AzwinCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Personnel

Feb 1990 v67 n2 p56(6)

Page 1

A guide to job enrichment and redesign.

by J. Barton Cunningham and Ted Eberle

The use of traditional methods for job design and redesign can have a negative impact on

productivity and employee morale. Four alternatives to the traditional approach are job

enrichment, the job characteristics model, Japanese-style management, and quality-of-worklife

approaches. The theories of job enrichment and the job characteristics model are based on job

content. Japanese-style management techniques focus on strong teamwork, job harmony, and

group goals. The quality-of-life approaches are based on improving an organizations design. A

suggested procedure for implementing a large-scale job redesign program involving 12 steps is

outlined.

COPYRIGHT American Management Association

1990

A Guide to Job Enrichment And Redesign

As many human resources professionals have discovered,

the traditional approach to job design can adversely affect

their organizations productivity as well as the motivation

and job satisfaction of employees. To overcome these

problems, various alternative approaches to job design

have been suggested, ranging from Japanese-style

management and quality circles to more general

applications of organization development and job

enrichment. Typically, these approaches seek to improve

an organizations coordination, productivity, and overall

product quality and to respond to employees needs for

learning, challenge, variety, increased responsibility, and

achievement.

Four of the more popular design alternatives - job

enrichment, the job-characteristics model, Japanese-style

management, and quality-of-worklife approaches - are

briefly described below. (The motivational assumptions,

critical techniques, and implementation procedures of

these alternatives are summarized in Exhibit 1.) The

remainder of the article focuses on the problems HR

professionals may encounter when attempting to

implement any of these approaches.

The Alternatives in a Nutshell

Frederick Herzbergs two-factor theory is one of the most

well-known approaches to job enrichment. He suggested

that the factors involved in producing job satisfaction (and

motivation) are separate and distinct from "hygiene"

factors, which lead to job dissatisfaction.

Growth and motivation factors include achievement,

recognition, the work itself, responsibility, and

advancement. Hygiene factors, in contrast, are associated

with the work context or environment. The most important

hygiene factor is company policy and administration. The

second most important factor is technical supervision. An

incompetent supervisor who lacks knowledge of the job or

the ability to delegate responsibility and teach, for

example, can cause dissatisfaction. Work conditions,

interpersonal relations with supervisors, salary, and the

lack of recognition and/or achievement also can cause

dissatisfaction.

According to Herzberg, motivating employees is entirely

different from reducing job dissatisfaction. Reducing job

dissatisfaction will not increase motivation but merely

reduce the level of employees dissatisfaction.

The job-characteristics model is based on the idea that

people will respond differently to the same job and that it is

possible to alter a jobs character to increase motivation,

satisfaction, and performance. The initial research on job

characteristics was concerned with the relationship

between certain objective attributes of tasks (such as

amount of task variety, level of autonomy, amount of

interaction required to carry out task activities and the

number of opportunities for optional interaction, level of

knowledge and skill required, and amount of responsibility

entrusted to the job holder) and employee reactions to the

tasks. Five job characteristics were developed in later

research: variety, task identity, task significance,

autonomy, and job-based feedback.

The job-characteristics model seeks to structure work so

that it can be performed effectively and is personally

rewarding and satisfying. According to this model,

matching people with their jobs will reduce the need to

urge them to perform well. Instead, workers will try to do

well because it is rewarding and satisfying to do so.

Japanese-style management practices have been

associated with high productivity, low turnover, and low

absenteeism. They evolved as a product of the

U.S.-guided post-World War II development of Japan

(which discouraged unionization) as well as of Japans

cultural heritage. However, no body of theory or scientific

evidence clearly illustrates that Japanese organization

design techniques will produce higher productivity and job

satisfaction in either Japanese or American work settings.

The Japanese management approach treats employees

- Reprinted with permission. Additional copying is prohibited. -

GALE GROUP

Information Integrity

Personnel

Feb 1990 v67 n2 p56(6)

Page 2

A guide to job enrichment and redesign.

according to family-like norms. Among those norms, "wa"

(harmony), is the component most often emphasized by

companies. "Wa" refers to a form of teamwork or group

consciousness. Individual employee actions are not

dominant in Japanese industry; in fact, they may be

discouraged because of the competition they can generate

among team members.

The development of organizational cohesiveness seems to

be a major objective of Japanese human resources

policies. Japanese companies seek to hire employees who

have moderate views and a harmonious personality as

well as ability to do the job. The socialization process

begins with an initial training program, which may last up

to six months and is geared toward familiarizing new

employees with the company. Employees can be

transferred to learn new skills; transfers are also part of a

long-range, experience-building program through which

the organization grooms future managers. By rotating from

job to job, employees become increasingly immersed in

the companys philosophy and culture.

Under conditions of lifetime employment, rapid promotion

is unlikely unless an organization is expanding

dramatically. Because of this limited upward mobility,

companies encourage lateral job rotation. These carefully

planned transfers provide some status and recognition

since not all jobs at the same hierarchical level are equal

in their centrality or importance to the organizations

activities. This movement provides or withholds

opportunities to learn skills that are required for future

formal promotions.

Quality-of-worklife approaches refer to the many

workplace experiments concerned with improving an

organizations design. The elements that are relevant to an

individuals quality of worklife include the task, the physical

work environment, the social environment within the

organization, the administrative system, and the

relationship between life on and off the job. The term

"quality of worklife" can be thought of as a replacement for

such previous terms as job design and socio-technical

designs.

Quality-of-worklife designs do not offer any standard set of

principles because they depend on the needs of the

technology as well as those of the individuals in the social

system. Essential to any quality-of-worklife application is

an understanding of the needs of the organizations social

and technical systems. The company must be committed

to understanding the relevant problems and issues and

adapting appropriated theories and techniques. It also

must recognize that individuals need to be involved in

designing the organizations they work in and that the

design may have to take into account an individuals

capacity to act in a certain way at a specific point in time.

No design will last forever; the process of redesign will

need to take into account new technologies and growing

individual capacities.

Because quality-of-worklife designs are based on the

individuals ability to make judgments about what is or is

not desirable in the workplace, managers and employees

must maintain an open dialog about the way the workplace

is designed and managed. Discussions can focus on

improving wages, hours of work, job security, safety, and

other work conditions. Employees "choices" can lead to

the development of particular kinds of jobs and

organizations that enable people to develop their abilities

and fulfill their needs in the workplace. The resulting jobs

may present greater opportunities for variety, challenge,

responsibility, and growth.

Why Problems Arise

Our experience with job enrichment and design ideas has

revealed several types of implementation problems. For

example, organizations sometimes are reluctant to commit

resources to longterm programs of change that maximize

worker input and participation. Some top executives

believe that job enrichment involves too many changes to

a job-classification plan and costs too much money.

We have had some limited success in encouraging job

analysts to make minor adjustments when they develop

new job descriptions and refocus job-classification plans.

Although our suggestions may compromise the integrity of

the pure theories of job design, we recognize that change

may be possible if we choose and adapt our design

techniques according to an organizations specific setting.

To classify a job, job analysts normally collect information

and then develop a job description, which becomes a

guide for determining the employees work, training needs,

and compensation. Job analysis also attempts to describe

and coordinate an organizations broader structure and

objectives, the tasks and skills required to achieve those

objectives, and the meaningful grouping of tasks and skills

into specific jobs.

Several approaches to job analysis focus on the singular

requirement of arranging job duties to respond to efficiency

and effectiveness criteria. Technological developments

have made it easier to break down jobs into simpler, more

specialized tasks. Work is designed in such a way that

tasks are simple; they are easy for everyone to perform

and do not rely on singular or gifted personnel.

Why cant job descriptions be used for focusing

job-enrichment efforts? Some job-analysis procedures

- Reprinted with permission. Additional copying is prohibited. -

GALE GROUP

Information Integrity

Personnel

Feb 1990 v67 n2 p56(6)

Page 3

A guide to job enrichment and redesign.

provide information on job features such as variety,

autonomy, challenge, feedback, and responsibility. The

assumption is that intrinsically rewarding jobs will make

employees more satisfied and productive.

Job-analysis procedures need to take into account the

effective grouping of tasks as well as employee motivation

and development. They must address the technical

requirements of coordinating people, techniques, tools,

and methods used to accomplish a set of tasks as well as

the social requirements of responding to employee needs,

expectations, and feelings about the work setting. An

effective job design meets both the requirements of the

tasks and the social and psychological needs of the

workers.

This sociotechnical concept grew out of the post-World

War II coal-mining studies by the Tavistock Institute of

Human Relations. It suggests that a design principle

cannot respond exclusively to the singular requirements of

either technical effectiveness or social satisfaction. What

counts is a balanced recognition of each systems needs,

not the satisfaction of one need at the expense of the

other. A sociotechnical assumption implies that a job

cannot be designed with machinelike standards and

minimal variety, challenge, and change. Moreover, it

should not be designed to respond solely to an individuals

wishes, idiosyncrasies, or selfish habits.

This sociotechnical concept suggests that job design can

make use of many of the techniques from the four models

described above. Which techniques to use depends on the

particular job and culture. In some organizations, it may be

more appropriate to highlight concepts of design that

emphasize team grouping; in others, to develop designs

that focus on more variety and participation.

Some Questions to Consider

The sociotechnical concept suggests that different

job-design approaches may be appropriate for different

change efforts. Generally the job-enrichment and

job-characteristics models focus on redesigning a job

structure using principles that alter the way the individual

carries out his or her work. They are "micro" models of

organizational and job design in that they deal with

operational/production jobs in which tasks can be defined

and broken down. These approaches are limited to

redesigning the way in which work is carried out; they do

not generally focus on controversial issues such as pay

and labor relations.

Japanese-style management and quality-of-worklife

programs focus more on the total organization, with

particular emphasis on improving the level of consultation

with employees. They are "macro" models of organization

design, although individual applications may emphasize

only specific aspects of the organization. Our experience

with quality-of-worklife approaches illustrates some

difficulties. We probably do not have enough data to

provide any evidence of the difficulties of applying

Japanese-style management in an American setting.

Generally companies have been much more interested in

applying quality-circle ideas than in trying to make U.S.

organizations more like those in Japan.

The sociotechnical concept also suggests that design

approaches must respond to worker needs as well as to

specific conditions or prerequisites within an organization.

Exhibit 2 suggests that job-enrichment and

job-characteristics approaches may be more appropriate

when workers express interest in gaining more

responsibility, growth, and the like. Some enrichment

techniques may be appropriate for the short term, while

others may be limited by the organizations technology or

job-classification plan. Thus, when introducing

enrichment-type programs, the following three questions

should be asked:

* Do employees need jobs that involve responsibility,

variety, feedback, challenge, accountability, significance,

and opportunities to learn?

* What techniques can be implemented without changing

the job-classification plan?

* What techniques would require changes in the

job-classification plan?

Japanese-style management and quality-of-worklife

programs also have unique prerequisites. Both focus on

enriching the workers job and cultivating the individual to

make him or her part of the organization. Interesting work

is only part of a larger package that focuses on career, life,

and identity with the organization.

We do not mean to imply that Japanese-style

management and sociotechnical-change programs are

similar. Although team decision making is prominent in

both programs, Japanese teams or problem-solving

groups are consultational in nature. Quality-of-worklife

programs strive to develop semiautonomous work groups

and shift power to workers.

This difference is central to an understanding of the role of

teamwork in these approaches. The

Japanese-management management approach suggests

that the organization take responsibility for the careers and

lives of its members. Quality-of-worklife programs imply a

democracy in which workers take responsibility for the

- Reprinted with permission. Additional copying is prohibited. -

GALE GROUP

Information Integrity

Personnel

Feb 1990 v67 n2 p56(6)

Page 4

A guide to job enrichment and redesign.

organization.

In assessing the organizations readiness for

Japanese-style management or quality-of-worklife

programs, a company should answer these questions:

* Do individuals want to work in teams to solve problems

or make decisions?

* Do employees need jobs that involve responsibility,

variety, feedback, challenge, accountability, significance,

and opportunities to learn?

* Do workers need to learn and grow in the organization, to

be part of its identity, and to assist in its corporate future?

* What organization-structure adjustments are needed to

respond to these design suggestions?

* How should the job-classification plan be altered to

respond to these structural changes?

rough idea of what the job consists of. We have learned to

rely on a process of open-ended interviewing to probe

about the job and the many underlying human elements

making it up. Each social system is unique, and much of

the information about worker preferences can best be

derived from such interviews.

4. Define the unique characteristics or constraints. Each

organization has particular characteristics or constraints,

such as the age of the work-force, the work setting, and

the job-classification plan. These characteristics should be

identified.

5. Develop a clustering of tasks. How do work tasks and

personal skills cluster on the basis of similar behaviors or

common requirements? Which tasks may be meaningfully

grouped together and defined as a job?

6. Develop a list of intervention techniques. In devising

such a list, it is helpful to pick the techniques that are

considered relevant based on the approaches defined in

this article.

A Suggested Procedure

We have used the following procedure in organizations

that have been reluctant to begin large-scale job-design

programs:

1. Define the systems goals. Select the organization,

system, or subsystem to be studied. Define which groups

of workers will be involved and how they relate to each

other. What are the broad objectives of the larger

organization - the department, plant, and company - of

which these jobs are a part? How is the organization

structured to accomplish these goals? What is the current

job-classification structure?

2. Define the relevant tasks and activities. What work tasks

lead to the accomplishment of the organizations

objectives? What unique managerial or personal skills are

required? What unique needs and aspirations do workers

in these jobs have? Managers should keep in mind the

function of the organization and the need to balance social

and technical requirements.

3. Interview. In conducting a job analysis, an analyst gets

information from the following sources: direct observation

or on-the-job experience; interviews with job incumbents

and their supervisors; meetings with higher-level

management and human resources representatives;

questionnaires or checklists completed by job incumbents,

their supervisors, and/or others familiar with the job;

psychological tests and ratings of requirements; and other

sources of available information such as training manuals

and existing job guides. The primary goal is to obtain a

7. Relate techniques to requirements and assumptions.

Managers can brainstorm to develop a list of techniques

and principles that may be appropriate for the job clusters.

8. Define the appropriate level of implementation.

Managers should clarify how each technique should be

implemented in the organization.

9. Pull it together in a picture. At this stage it is sometimes

useful to draw a picture of what has been accomplished

thus far.

10. Screen generalities. Screen the list of techniques to

eliminate generalities or vague statements that do not

specify implementation plans.

11. Develop a process of implementation. The process of

implementation is as important as the theory of design. It is

important to define the forces that may aid implementation

and those that may hinder it. It is also necessary to screen

the list of design techniques for those that cannot be

implemented without changing the job-classification plan.

A separate process of implementation is required for

job-classification plan changes.

12. Adapt the job description and process of design. The

job description and process should be reviewed and

altered as the organizations critical requirements change.

Any discussion of approaches to job and organization

design must take into account an organizations needs and

requirements, paying particular attention to employees

- Reprinted with permission. Additional copying is prohibited. -

GALE GROUP

Information Integrity

Personnel

Feb 1990 v67 n2 p56(6)

Page 5

A guide to job enrichment and redesign.

interpersonal and job preferences. We have highlighted

the prerequisites necessary for implementing certain

approaches to job and organization design. Our underlying

assumption is that the success of job-design ideas often

depends on the organizations ability to change job

descriptions.

J. Barton Cunningham is an associate professor at the

University of Victoria in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

He is currently working on projects in crisis management,

entrepreneurship, management skills, and quality of

worklife. He has a Ph.D. degree in management and

administrative studies from the University of Southern

California. Ted Eberle has worked as a personnel

manager and human resources consultant. He is now

vice-president of human resources at a hospital in Alberta,

Canada. He has a masters degree in public administration

from the University of Victoria

- Reprinted with permission. Additional copying is prohibited. -

GALE GROUP

Information Integrity

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Impact of Non Financial Rewards On Employee Motivation in Apparel Industry in Nuwaraeliya DistrictDokument12 SeitenThe Impact of Non Financial Rewards On Employee Motivation in Apparel Industry in Nuwaraeliya Districtgeethanjali champikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.6challenges and Opportunity For Organization Behaviour 1Dokument13 Seiten1.6challenges and Opportunity For Organization Behaviour 1Balakrishna Nalawade N0% (1)

- IncentivesDokument27 SeitenIncentivesNiwas BenedictNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job Design and Employee Performance of Deposit Money Banks in Port Harcourt, NigeriaDokument7 SeitenJob Design and Employee Performance of Deposit Money Banks in Port Harcourt, NigeriaEditor IJTSRDNoch keine Bewertungen

- ComMgt ch02 Reward SystemDokument24 SeitenComMgt ch02 Reward SystemFarhana MituNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mba Semester 1: Mb0043 Human Resource Management 3 Credits (Book Id: B0909) Assignment Set - 1Dokument17 SeitenMba Semester 1: Mb0043 Human Resource Management 3 Credits (Book Id: B0909) Assignment Set - 1Mohammed AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 3: Human Resource Management: Assignment BriefDokument4 SeitenUnit 3: Human Resource Management: Assignment BriefGharis Soomro100% (1)

- Managers vs NonmanagersDokument7 SeitenManagers vs Nonmanagersashek123mNoch keine Bewertungen

- MANAGEMENT FUNCTIONSDokument3 SeitenMANAGEMENT FUNCTIONSEza Nagk EzsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Employee Performance On Organizational Commitment, Transformational Leadership and Job Satisfaction in Banking Sector of MalaysiaDokument9 SeitenEffect of Employee Performance On Organizational Commitment, Transformational Leadership and Job Satisfaction in Banking Sector of MalaysiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job Analysis AssignmentDokument5 SeitenJob Analysis AssignmentLaiba khan100% (1)

- Reappraisal most effective for mitigating boredomDokument1 SeiteReappraisal most effective for mitigating boredomFarah HanisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job EnrichmentDokument44 SeitenJob Enrichmentkuldeep_chand10100% (1)

- Business Case For Assignment Quiz 2Dokument10 SeitenBusiness Case For Assignment Quiz 2Kamil Al Ashik 1610289630Noch keine Bewertungen

- Employee Performance AppraisalsDokument8 SeitenEmployee Performance AppraisalsPooja ChaudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effect Of Promotion And Compensation Toward Working Productivity Through Job Satisfaction And Working Motivation Of Employees In The Department Of Water And Mineral Resources Energy North Aceh DistrictDokument8 SeitenThe Effect Of Promotion And Compensation Toward Working Productivity Through Job Satisfaction And Working Motivation Of Employees In The Department Of Water And Mineral Resources Energy North Aceh DistrictinventionjournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proposal On Non-Financial RewardsDokument30 SeitenProposal On Non-Financial RewardsKime100% (1)

- Employee Motivation PresentationDokument22 SeitenEmployee Motivation PresentationManerly Flodeilla SalvatoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maslow - Applications and CriticismDokument6 SeitenMaslow - Applications and CriticismDana DanutzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The International Journal of Human Resource ManagementDokument33 SeitenThe International Journal of Human Resource ManagementAhmar ChNoch keine Bewertungen

- Importance of Strategic Human Resource ManagementDokument14 SeitenImportance of Strategic Human Resource ManagementAngelo VillalobosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment One Human Resource Management (MGT211) Deadline: 06/03/2021 at 23:59Dokument4 SeitenAssignment One Human Resource Management (MGT211) Deadline: 06/03/2021 at 23:59habibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vidyavardhini’s Compensation Management ProjectDokument27 SeitenVidyavardhini’s Compensation Management ProjectUlpesh SolankiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Training & Development Program On Employee of Jamuna Bank Limited''Dokument13 SeitenTraining & Development Program On Employee of Jamuna Bank Limited''Shibajit Halder0% (1)

- Motivation Theories and Job Design ExplainedDokument22 SeitenMotivation Theories and Job Design ExplainedMD FAISALNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Approaches To Organizing Human ResourcesDokument12 SeitenNew Approaches To Organizing Human ResourcesĐào Minh Quân TrầnNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBA S1 MHC 0415-0715 Set 1Dokument4 SeitenMBA S1 MHC 0415-0715 Set 1Sumit SullereNoch keine Bewertungen

- MG 370 Term PaperDokument12 SeitenMG 370 Term PaperDaltonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 5Dokument6 SeitenModule 5AllanCuartaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment # 1: Overview of HRMDokument1 SeiteAssessment # 1: Overview of HRMAlejandro Canca ManceraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Questionnaire On Learning N DevelopmentDokument4 SeitenQuestionnaire On Learning N DevelopmentsptharunNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Engagement Gap: Executives and Employees Think Differently About Employee EngagementDokument17 SeitenThe Engagement Gap: Executives and Employees Think Differently About Employee Engagementabalizar8819Noch keine Bewertungen

- Performance Management Practices, Employee Attitudes and Managed PerformanceDokument24 SeitenPerformance Management Practices, Employee Attitudes and Managed PerformanceMuhammad Naeem100% (1)

- Managing organizational changes at Prestige InstituteDokument6 SeitenManaging organizational changes at Prestige InstitutePooja PandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource ManagementDokument13 SeitenHuman Resource ManagementKshipra PanseNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Interviewing CandidatesDokument6 Seiten7 Interviewing CandidatesAbdoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Functional Departmentalization - Advantages and DisadvantagesDokument5 SeitenFunctional Departmentalization - Advantages and DisadvantagesCheAzahariCheAhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employee WellbeingDokument6 SeitenEmployee WellbeingKushal BajracharyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Workforce Focus: By: Sherilyn D Maca Raig, MbaDokument33 SeitenWorkforce Focus: By: Sherilyn D Maca Raig, MbaSherilyn MacaraigNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tata Mutual Fund 2Dokument14 SeitenTata Mutual Fund 2mahesh2037100% (1)

- DENR Career Development System 30 July 2020 PDFDokument62 SeitenDENR Career Development System 30 July 2020 PDFKris NageraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psy 3711 First Midterm QuestionsDokument14 SeitenPsy 3711 First Midterm QuestionsShiv PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study of MotivationDokument39 SeitenA Study of MotivationRavi JoshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Performance Appraisal of EmployeesDokument7 SeitenPerformance Appraisal of EmployeesHarry olardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Affecting Org ClimateDokument2 SeitenFactors Affecting Org ClimatevsgunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recruitment Factors at BankDokument16 SeitenRecruitment Factors at BankAkshay PArakh100% (3)

- Employee involvement strategies to boost quality of work lifeDokument4 SeitenEmployee involvement strategies to boost quality of work lifescribdmanisha100% (1)

- Managing People and Organizations.: Assignment - Learning Outcome 01Dokument27 SeitenManaging People and Organizations.: Assignment - Learning Outcome 01Namali De Silva0% (1)

- Chapter 2serdtfyguhipDokument30 SeitenChapter 2serdtfyguhipMuchtar ZarkasyiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ba7031 Managerial Behaviour and Effectiveness PDFDokument117 SeitenBa7031 Managerial Behaviour and Effectiveness PDFAppex TechnologiesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Sharmistha Bhattacharjee 470 Research Article Oct 2011Dokument18 Seiten2 Sharmistha Bhattacharjee 470 Research Article Oct 2011Deepti PiplaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employee Motivatio N: Submitted By: John Paul M. Mira Submitted ToDokument4 SeitenEmployee Motivatio N: Submitted By: John Paul M. Mira Submitted ToEWANko143100% (1)

- 1Dokument2 Seiten1Ana AnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Need For Sustainable Development in Policy Making For Job Satisfaction Level of Lecturers Working in Private Universities and CollegesDokument7 SeitenNeed For Sustainable Development in Policy Making For Job Satisfaction Level of Lecturers Working in Private Universities and CollegesDr Anuj WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource Management (Notes Theory)Dokument31 SeitenHuman Resource Management (Notes Theory)Sandeep SahadeokarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Human Resource Management PrinciplesDokument23 SeitenStrategic Human Resource Management PrinciplesBhaveshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Performance Appraisal Methods and TechniquesDokument33 SeitenPerformance Appraisal Methods and TechniquesSara taskeenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summer Internship Project Report On Performance AppraisalDokument24 SeitenSummer Internship Project Report On Performance AppraisalROSHI1988100% (1)

- Talent ManagementDokument2 SeitenTalent ManagementAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team Work and CollaborationDokument1 SeiteTeam Work and CollaborationAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Productivity For Dummies Cheat Sheet: Boosting Performance at WorkDokument3 SeitenProductivity For Dummies Cheat Sheet: Boosting Performance at WorkAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neural Correlates of Four Broad Temperament DimensionsDokument9 SeitenNeural Correlates of Four Broad Temperament DimensionsAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Af 42Dokument6 SeitenAf 42AzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conducting Effective MeetingsDokument1 SeiteConducting Effective MeetingsAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- 49 158 1 PBDokument8 Seiten49 158 1 PBIndra ZulhijayantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Association of CoachingDokument2 SeitenInternational Association of CoachingAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role Ambiguity Role Efficacy and Role PeDokument14 SeitenRole Ambiguity Role Efficacy and Role PeAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Journal) Celissa C. Verpaelst & Lionel G. Standing - Demand Characteristics of Music Affect Performance On The WPT of IntelligenceDokument2 Seiten(Journal) Celissa C. Verpaelst & Lionel G. Standing - Demand Characteristics of Music Affect Performance On The WPT of IntelligenceAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Journal) Rebecca Rosenstein - Type Size and Performance of The Elderly On The Wonderlic Personnel TestDokument8 Seiten(Journal) Rebecca Rosenstein - Type Size and Performance of The Elderly On The Wonderlic Personnel TestAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mckelvie 1989Dokument2 SeitenMckelvie 1989MNSTRNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Journal) Stuart J. Mckelvie - Validity and Reliability Findings For An Experimental Short Form of The WPT in An Academic SettingDokument4 Seiten(Journal) Stuart J. Mckelvie - Validity and Reliability Findings For An Experimental Short Form of The WPT in An Academic SettingAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Worldwide Association of Business CoachesDokument1 SeiteWorldwide Association of Business CoachesAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Integration in the WorkplaceDokument21 SeitenSocial Integration in the WorkplaceAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- M. Salanova W. Schaufeli - A Cross-National Study of Work Engagement As A Mediator Between Job Resources and Proactive BehaviourDokument17 SeitenM. Salanova W. Schaufeli - A Cross-National Study of Work Engagement As A Mediator Between Job Resources and Proactive BehaviourAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schultze 2006Dokument4 SeitenSchultze 2006AzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive ModelingDokument1 SeiteCognitive ModelingAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To BI Rate - Bank Sentral Republik IndonesiaDokument1 SeiteIntroduction To BI Rate - Bank Sentral Republik IndonesiaAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- BI 7-Day (Reverse) Repo RateDokument1 SeiteBI 7-Day (Reverse) Repo RateAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jennifer Walinga - Toward A Theory of Change Readiness The Roles of Appraisal, Focus, and Perceived ControlDokument33 SeitenJennifer Walinga - Toward A Theory of Change Readiness The Roles of Appraisal, Focus, and Perceived ControlAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Skills Inventory For Excel: BasicDokument1 SeiteSkills Inventory For Excel: BasicOliviaDuchessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Top 15 Principles for Effective Talent MetricsDokument3 SeitenTop 15 Principles for Effective Talent MetricsAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organizational SocializationDokument16 SeitenOrganizational SocializationAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Identify Promotable EmployeesDokument1 SeiteHow To Identify Promotable EmployeesAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steps in Human Resource Planning Explained With DiagramDokument2 SeitenSteps in Human Resource Planning Explained With DiagramAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- BI 7-Day (Reverse) Repo RateDokument1 SeiteBI 7-Day (Reverse) Repo RateAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychoanalytic Cyberpsychology: Contemporary Media ForumDokument6 SeitenPsychoanalytic Cyberpsychology: Contemporary Media ForumAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manpower Planning (MP) Meaning, Steps and Techniques Manpower PlanningDokument8 SeitenManpower Planning (MP) Meaning, Steps and Techniques Manpower PlanningAzwinNoch keine Bewertungen

- E-Recruitment Pros vs ConsDokument6 SeitenE-Recruitment Pros vs ConsArshin AfnNoch keine Bewertungen

- PG Ns Timetable April2016Dokument38 SeitenPG Ns Timetable April2016starscrawlNoch keine Bewertungen

- COPAR Phases and Nurse ResponsibilitiesDokument17 SeitenCOPAR Phases and Nurse ResponsibilitiesIlyka Fe PañaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 8 Learners' Difficulties in Writing ParagraphsDokument26 SeitenGrade 8 Learners' Difficulties in Writing ParagraphsBetel Niguse100% (2)

- Semantics and PragmaticsDokument8 SeitenSemantics and PragmaticsMohamad SuhaimiNoch keine Bewertungen

- NurhawaryDokument77 SeitenNurhawaryKomin Melly ArsantimasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baby Thesis Sa Filipino Tungkol Sa EdukasyonDokument8 SeitenBaby Thesis Sa Filipino Tungkol Sa Edukasyonevkrjniig100% (1)

- KPF Resume 2020Dokument2 SeitenKPF Resume 2020api-506356996Noch keine Bewertungen

- Smith - A Place Called Irony (Everything You Know About Indians Is Wrong)Dokument6 SeitenSmith - A Place Called Irony (Everything You Know About Indians Is Wrong)Paul GuillenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sangeeta ResumeDokument3 SeitenSangeeta ResumeShiv KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- AbheyRana 20154015 CSE MNNIT AllahabadDokument1 SeiteAbheyRana 20154015 CSE MNNIT AllahabadMangesh LokhandeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Detail Map of ChauddagramDokument4 SeitenDetail Map of ChauddagramalauddinaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Core Competencies For RegulatorsDokument3 SeitenThe Core Competencies For RegulatorsANoch keine Bewertungen

- Teori Apple and Muysken (1987)Dokument3 SeitenTeori Apple and Muysken (1987)Nadhirah AfendiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jharkhand ResumeDokument2 SeitenJharkhand ResumeRahul kumar guptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electronic Class Record GRADES 1 To 10 : InstructionsDokument38 SeitenElectronic Class Record GRADES 1 To 10 : InstructionsMark Angelbert Angcon DeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy of EducationDokument31 SeitenPhilosophy of EducationHarking Castro Reyes100% (3)

- Cchms Sec 3el Mye Paper 2 (Sections A B)Dokument6 SeitenCchms Sec 3el Mye Paper 2 (Sections A B)Samy RajooNoch keine Bewertungen

- FKE Handbook 20192020Dokument166 SeitenFKE Handbook 20192020Sharin Bin Ab GhaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ministry of Health Malaysia releases updated credentialing guidelinesDokument142 SeitenMinistry of Health Malaysia releases updated credentialing guidelinesFirdaus Al HafizNoch keine Bewertungen

- For A Pedagogy of Reading in The Digital/ Postmodern AgeDokument9 SeitenFor A Pedagogy of Reading in The Digital/ Postmodern AgeAnonymous i7rJbl0% (1)

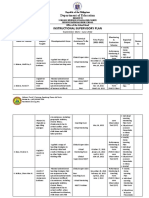

- Philippine Education Dept Instructional PlanDokument9 SeitenPhilippine Education Dept Instructional PlanIVY HISONoch keine Bewertungen

- Edtc645 Qureshi Interview ReportDokument22 SeitenEdtc645 Qureshi Interview Reportapi-550210411Noch keine Bewertungen

- Scribd 2Dokument80 SeitenScribd 2Victor CantuárioNoch keine Bewertungen

- SF2-SHS Attendance ReportDokument4 SeitenSF2-SHS Attendance ReportJayson Dotimas VelascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Professional Development Review GuidanceDokument2 SeitenProfessional Development Review GuidancekennyNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Teaching PortfolioDokument53 SeitenMy Teaching Portfolioapi-352940643Noch keine Bewertungen

- CLASS TEST FOR NSIT StudentsDokument2 SeitenCLASS TEST FOR NSIT StudentsAnirudh MittalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 5 Essay QuestionsDokument5 SeitenChapter 5 Essay Questionsapi-462929132Noch keine Bewertungen

- PTC Design Engineers With Simulation 2Dokument19 SeitenPTC Design Engineers With Simulation 2Ashish ParasharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aspaen Colegio El Rosario Math Study Guide First GradeDokument34 SeitenAspaen Colegio El Rosario Math Study Guide First GradeYARLY JOHANA TAMAYO GUZMANNoch keine Bewertungen