Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

2012 Sleep Medicine 13 207-210

Hochgeladen von

AlexisMolinaCampuzanoCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

2012 Sleep Medicine 13 207-210

Hochgeladen von

AlexisMolinaCampuzanoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51882962

The Spanish version of the Insomnia Severity

Index: A confirmatory factor analysis

ARTICLE in SLEEP MEDICINE DECEMBER 2011

Impact Factor: 3.15 DOI: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.06.019 Source: PubMed

CITATIONS

READS

11

359

7 AUTHORS, INCLUDING:

Julio Fernandez-Mendoza

Alfredo Rodriguez-Muoz

Penn State Hershey Medical Center and Pe

Complutense University of Madrid

83 PUBLICATIONS 851 CITATIONS

77 PUBLICATIONS 672 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

SEE PROFILE

Sara Olavarrieta-Bernardino

Edward Bixler

Universidad Autnoma de Madrid

Pennsylvania State University

22 PUBLICATIONS 190 CITATIONS

292 PUBLICATIONS 15,124 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All in-text references underlined in blue are linked to publications on ResearchGate,

letting you access and read them immediately.

SEE PROFILE

Available from: Julio Fernandez-Mendoza

Retrieved on: 11 April 2016

Author's personal copy

Sleep Medicine 13 (2012) 207210

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Sleep Medicine

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/sleep

Original Article

The Spanish version of the Insomnia Severity Index: A conrmatory factor analysis

Julio Fernandez-Mendoza a,, Alfredo Rodriguez-Muoz b, Antonio Vela-Bueno c,

Sara Olavarrieta-Bernardino c, Susan L. Calhoun a, Edward O. Bixler a, Alexandros N. Vgontzas a

a

Sleep Research and Treatment Center, Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, Penn State University, Hershey, PA, USA

Department of Social Psychology, School of Psychology, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain

c

Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Universidad Autnoma de Madrid, Spain

b

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 7 March 2011

Received in revised form 10 June 2011

Accepted 11 June 2011

Available online 14 December 2011

Keywords:

Insomnia Severity Index

Spanish

Psychometric properties

Conrmatory factor analysis

Validation

Mood

Fatigue

a b s t r a c t

Objective: To examine the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Insomnia Severity Index

(ISI) and to determine its factor structure with conrmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Methods: Self-reported information was collected from a sample of 500 adults (mean age 39.13 [standard

deviation 15.85] years) drawn from a population of medical students and their social networks. Together

with the ISI, a measure of the subjective severity of insomnia, subjects completed the Pittsburg Sleep

Quality Index, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and the Prole of Mood States to study concurrent validity

of the ISI. CFA was used to test alternative models to ascertain the factorial structure of the ISI.

Results: The Spanish version of the ISI showed adequate indices of internal consistency (Cronbachs

a = 0.82). CFA showed that a three-factor structure provided a better t to the data than one-factor

and two-factor structures. The ISI was signicantly correlated with poor sleep quality, fatigue, anxiety,

and depression, and discriminated between good and poor sleepers.

Conclusions: The ISI is a reliable and valid instrument to assess the subjective severity of insomnia in

Spanish-speaking populations. Its three-factor structure (i.e., night-time sleep difculties, sleep dissatisfaction and daytime impact of insomnia) makes it a psychometrically robust and clinically useful

measure.

2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder, with prevalence in

the general population ranging from 9% for chronic insomnia to 30%

for occasional sleep difculties or poor sleep [1]. Brief, easyto-administer, and valid patient-reported questionnaires to screen

and assess for insomnia are needed for clinical practice and

research.

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) [2] is a brief self-report instrument measuring a patients perception of the severity of his/her

insomnia. The ISI captures, in part, the diagnostic criteria for

insomnia outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders [3] and the International Classication of Sleep

Disorders [4]. The ISI comprises seven items targeting the severity

of sleep onset difculties, sleep maintenance difculties, and early

morning awakening; satisfaction with current sleep; interference

Corresponding author. Address: Sleep Research and Treatment Center, Department of Psychiatry, Penn State College of Medicine, 500 University Drive H073,

Hershey, PA 17033, USA. Tel.: +1 7175310003x285570.

E-mail address: jfernandezmendoza@hmc.psu.edu (J. Fernandez-Mendoza).

1389-9457/$ - see front matter 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2011.06.019

with daily functioning; noticeability of impairment attributed to

the sleep problem; and degree of distress or concern caused by

the sleep problem.

To date, the psychometric properties of the English [2,5,6],

French [7], Spanish [8], and Chinese [9,10] versions of the ISI have

been examined. These previous studies have shown that the ISI is

a reliable instrument and that its concurrent validity with other

questionnaires or sleep diaries is adequate [2,510]. Moreover,

the factor structure of the ISI has only been examined using

exploratory factor analysis, with mixed and inconsistent results

[2,5,7,8,10]. No studies to date have used conrmatory factor

analysis (CFA) to explore the factor structure of the ISI. Therefore,

it is unknown which factor structures reported in the literature best

explain the structure of the ISI.

Preliminary evidence suggests that the Spanish version of the

ISI has adequate psychometric properties. However, this evidence

comes from a study that used a relatively small, very homogenous

group of older adults that participated in a cognitive rehabilitation

programme [8]. Acknowledging that Spanish is the second most

spoken language in the world, it is essential to develop and validate

patient-reported instruments to assess insomnia in Spanishspeaking populations. This study aimed to validate the Spanish

version of the ISI using CFA.

Author's personal copy

208

J. Fernandez-Mendoza et al. / Sleep Medicine 13 (2012) 207210

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Five hundred adults from the general population (307 females,

mean age 39.13 [standard deviation 15.85] years, range

1970 years) were recruited by a snowball technique [11] in

which third-year medical students and two adults (age P35 years)

from each students social network (typically their relatives) were

invited to participate in a research survey on vulnerability to

insomnia during October and November 2007 [12]. All subjects

anonymously completed a survey packet that included published

self-report questionnaires that have shown acceptable indexes of

validity and reliability in their original versions. The study and

all procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board

of the Universidad Autonoma of Madrid (CEI 20-417), and written

informed consent was obtained from all individuals. The characteristics of the sample are available online as Supplementary material.

2.2. Measures

The survey collected sociodemographic information from the

subjects (e.g., gender, age, weight, height) [12]. The Spanish version

of the ISI was used to assess the subjective severity of insomnia

over a 1-week period [13]. Each item was rated on a ve-point Likert scale (e.g., 0 = no problem, 4 = very severe problem), yielding a

total score ranging from 0 to 28 [2]. Subjects also completed the

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [14], the Epworth Sleepiness

Scale (ESS) [15], and the depression, anxiety, and fatigue scales of

the Prole of Mood States (POMS) [16].

2.3. Statistical analyses

The analysis consisted of three steps. First, the reliability of the

questionnaire was examined by calculating its internal consistency

with Cronbachs a. Second, CFA of the items was performed to

examine the structure of the questionnaire. Maximum likelihood

estimation was employed using a covariance matrix [17]. Specic

details about the CFA procedure, goodness-of-t indices, and their

references are provided online as Supplementary material. Third,

to determine concurrent validity, zero-order correlation analyses

between the ISI scales and other, theoretically related, constructs

were performed. Statistical analyses were performed using

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 15.0 (SPSS Inc.,

Chicago, IL, USA) and AMOS Version 17.0 [18].

3. Results

Cronbachs a for the ISI was 0.82. The items were homogeneous

since the corrected item-to-total correlation for the items ranged

from 0.47 to 0.71 (see online Supplementary material).

Three alternative factor models were tested using CFA. Model 1

(M1) was proposed as the null hypothesis, which postulated a

single factor on which all the items load. Model 2 (M2) postulated

a two-factor structure with correlated factors, similar to the factor

solution found in previous studies [7,9,10]. Model 3 (M3) proposed

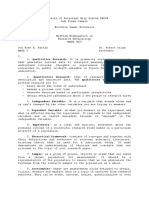

a three-factor structure with two correlated factors [2]. Table 1 displays the t indices of the competing models, as well as the model

comparisons.

M3 provided a better t to the data, according to the Chisquared difference, compared with M1 (Dv2 = 235.99, Dd.f. = 5,

P < 0.001) and M2 (Dv2 = 119.4, Dd.f. = 4; P < 0.001). In addition,

in terms of t indices and parsimony, M3 showed the best t of

goodness-of-t index, comparative t index, NNFI, non-normed

t index, root mean square residual and Akaike information

Table 1

Fit indices for the estimated models (N = 500).

Model

v2

d.f.

CFI

GFI

NNFI

RMR

AIC

One factor model

Two factor model

Three factor model

267.64

151.05

31.65

14

13

9

0.79

0.89

0.98

0.84

0.91

0.98

0.69

0.82

0.95

0.09

0.06

0.03

295.64

181.05

69.65

CFI, comparative t index; GFI, goodness-of-t index; RMR, root mean square

residual; NNFI, non-normed t index; AIC, Akaike information criterion.

Levels P0.90 for GFI, CFI, and NNFI, and 60.08 for RMR indicate that the models t

the data well. As a rule of thumb, the model with the smallest AIC value is considered to be the best model.

criterion (see Table 1). The three factors in M3 were named

night-time sleep difculties (Item 1, sleep onset; Item 2, sleep

maintenance; Item 3, early morning awakening), impact of

insomnia (Item 5, interference; Item 6, noticeability; Item 7, distress), and sleep dissatisfaction (Item 1, sleep onset; Item 4, satisfaction; Item 7, distress) [2]. Cronbachs a for these factors was

0.60, 0.81 and 0.75 for night-time sleep difculties, impact of

insomnia and sleep dissatisfaction, respectively. Mean inter-item

correlations were 0.35 (night-time sleep difculties), 0.59 (impact

of insomnia), and 0.50 (sleep dissatisfaction).

As shown in Table 2, concurrent validity analyses indicate that

the ISI and its three factors show signicant correlation with the

PSQI and the anxiety, depression, and fatigue scales of the POMS,

and weak to non-signicant correlation with the ESS. Moreover,

85% of subjects classied as insomniacs in the ISI (total score

P8) [7] were classied as poor sleepers in the PSQI (total score

>5), and 33% of non-insomniacs were classied as poor sleepers

(P < 0.0001).

4. Discussion

The ndings of the present study suggest that the ISI is a reliable

and valid instrument to assess the subjective severity of insomnia

in Spanish-speaking populations. Furthermore, this study gives

conrmatory support to the three-factor structure of the ISI, which

covers the severity of night-time sleep difculties, sleep dissatisfaction, and daytime impact of insomnia. Thus, the ISI is a psychometrically robust and clinically useful measure.

Previous studies have reported on the factor structure of the ISI

using exploratory analysis, but the results have been mixed and

inconsistent. Bastien et al. [2] rst proposed a three-factor structure

of the ISI (i.e., night-time sleep difculties, sleep dissatisfaction, and

daytime impact of insomnia) that explained 72% of the total variance in a clinical sample of middle-aged insomniacs. Savard et al.

[7], in two samples of cancer patients, reported a two-factor structure of the ISI (i.e., night-time sleep difculties and daytime impact

of insomnia) that explained between 58% and 62% of the total variance. Sierra et al. [8], using the Spanish version of the ISI in a group

of older adults, reported a one-factor solution that explained 69% of

the total variance. Finally, Yu [9] explored the factor structure of the

Chinese version of the ISI and found a two-factor solution (i.e.,

night-time sleep difculties and daytime impact of insomnia) that

explained 61% of the total variance. A similar two-factor solution

has been found in a Chinese sample of adolescents [10]. The present

study tested these alternative models against each other using CFA,

and found that the three-factor model best explains the structure of

the Spanish version of the ISI. Therefore, this study, using the Spanish version of the ISI in a non-clinical sample of young and middleaged adults, gives conrmatory support to the exploratory factor

structure obtained by Bastien et al. [2] in a clinical sample of middle-aged insomniacs.

Furthermore, the present results suggest that changes in the

total ISI score (primary outcome) and each of the three factors

Author's personal copy

J. Fernandez-Mendoza et al. / Sleep Medicine 13 (2012) 207210

Table 2

Correlations between ISI and other constructs (N = 500).

Impact of insomnia

Sleep dissatisfaction

Sleep difculties

Total score

PSQI

ESS

POMS

fatigue

POMS

depression

POMS

anxiety

0.49**

0.68**

0.62**

0.68**

0.26**

0.11*

0.04

0.18**

0.45**

0.34**

0.23**

0.40**

0.38**

0.27**

0.22**

0.34**

0.41**

0.33**

0.23**

0.38**

PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; POMS, Prole

of Mood States.

*

P < 0.05.

**

P < 0.01.

(secondary outcomes) should be examined in clinical practice and

treatment studies. The ISI provides a brief measure to examine

whether treatment for insomnia not only targets night-time sleep

difculties and sleep dissatisfaction, but also the impact of the disorder on daytime functioning (e.g., daytime fatigue, ability to function at work/daily chores, quality of life, etc.).

In the present study, the ISI correlated positively and moderately with the PSQI. The vast majority of individuals classied as

insomniacs with the ISI (85%) were classied as poor sleepers with

the PSQI. Also, the ISI correlated signicantly with the depression

and anxiety scales of the POMS, a nding that is consistent with

previous studies [12,19]. Taken together, these data provide adequate concurrent validity for the ISI. Interestingly, the ISI correlated more strongly with fatigue than sleepiness. Sleepiness has

been dened as a subjective feeling of physical and mental tiredness associated with increased sleep propensity, whereas fatigue

is a subjective feeling of physical or mental tiredness that is not

associated with increased sleep propensity [20]. Insomniacs, in

209

spite of their subjective complaints of daytime fatigue and signicantly less nocturnal sleep, do not show increased sleepiness compared with normal sleepers [20], which suggests that insomnia is a

condition of 24-h hyperarousal.

This study has several limitations. First, part of the sample was

drawn from a population of medical undergraduates, so the results

should be generalized with caution. Second, the concurrent validity

of the ISI should be explored against other scales that specically

assess the severity of insomnia, and not just general sleep quality

as measured by the PSQI. Third, the absence of a clinical diagnosis

of insomnia in this Spanish validation did not allow the sensitivity

and specicity of the ISI cut-off scores to be determined

empirically. Finally, it would be interesting to test the linguistic

properties of the ISI in other Spanish-speaking populations. As

there are fewer regional differences in written Spanish than, for

example, written English, the authors believe that the Spanish

version of the ISI can be used in different Spanish-speaking

populations (Fig. 1).

Notwithstanding these limitations, it is concluded that the ISI

is a reliable and valid instrument to assess the subjective severity

of insomnia in Spanish-speaking populations. Its three-factor

structure (i.e., severity of night-time sleep difculties, sleep

dissatisfaction, and daytime impact of insomnia) supports the

ISI as a psychometrically robust and clinically useful measure.

Conicts of interest

The ICMJE Uniform Disclosure Form for Potential Conicts of

Interest associated with this article can be viewed by clicking on

the following link: doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2011.06.019.

Fig. 1. Path representation of the proposed three-factor model.

Author's personal copy

210

J. Fernandez-Mendoza et al. / Sleep Medicine 13 (2012) 207210

References

[1] National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health State of the Science

Conference statement on manifestations and management of chronic insomnia

in adults, June 1315, 2005. Sleep 2005;28:104957.

[2] Bastien CH, Vallires A, Morin CM. Validation of the insomnia severity index as

a clinical outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2001;2:297307.

[3] American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

disorders. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

[4] American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classication of sleep

disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. 2nd edn. Westchester: American

Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.

[5] Smith S, Trinder J. Detecting insomnia: comparison of four self-report

measures of sleep in a young adult population. J Sleep Res 2001;10:22935.

[6] Morin CM, Belleville G, Blanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index:

psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment

response. Sleep 2011;34:6018.

[7] Savard MH, Savard J, Simard S, Ivers H. Empirical validation of the Insomnia

Severity Index in cancer patients. Psychooncology 2005;14:42941.

[8] Sierra JC, Guilln-Serrano V, Santos-Iglesias P. Insomnia Severity Index: some

indicators about its reliability and validity on an older adult sample. Rev

Neurol 2008;47:56670.

[9] Yu DS. Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric properties with Chinese

community-dwelling older people. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:23509.

[10] Chung KF, Kan KK, Yeung WF. Assessing insomnia in adolescents: comparison

of Insomnia Severity Index, Athens Insomnia Scale and Sleep Quality Index.

Sleep Med 2011; doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2010.09.019.

[11] Thompson SK. Sampling. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1992.

[12] Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vela-Bueno A, Vgontzas AN, et al. Cognitive-emotional

hyperarousal as a premorbid characteristic of individuals vulnerable to

insomnia. Psychosom Med 2010;72:397403.

[13] Morin CM. Insomnio: asistencia y tratamiento psicolgico. Barcelona: Ariel;

1998.

[14] Macias JA, Royuela A. La versin espaola del ndice de calidad del sueo de

Pittsburg [The Spanish version of the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index]. Inf

Psiquiatr 1996;146:46572.

[15] Arce-Fernandez C, Andrade-Fernandez EM, Seoane-Pesqueira G. Problemas

semnticos en la adaptacin del POMS al castellano [Semantic problems in the

Spanish adaptation of the POMS]. Psicothema 2000;12:4751.

[16] Izquierdo-Vicario Y, Ramos-Platon MJ, Conesa-Peraleja D, Lozano-Parra AB,

Espinar-Sierra J. Epworth sleepiness scale in a sample of the Spanish

population. Sleep 1997;20:6767.

[17] Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum; 2002.

[18] Arbuckle JL. AMOS 17.0 Users Guide. Crawfordville, FL: Amos Development

Corporation; 2008.

[19] Bluestein D, Rutledge CM, Healey AC. Psychosocial correlates of insomnia

severity in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med 2010;23:20411.

[20] Vgontzas AN, Zoumakis E, Papanicolaou DA, et al. Chronic insomnia is

associated with a shift of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor secretion

from nighttime to daytime. Metabolism 2002;51:88792.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Review of Clinical EEGDokument200 SeitenReview of Clinical EEGtuanamg66100% (10)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Coping With Health AnxietyDokument24 SeitenCoping With Health AnxietyAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canmat 2013Dokument44 SeitenCanmat 2013Lucas GmrNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Maybe 2 PDFDokument18 SeitenMaybe 2 PDFSheryl ElitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Ghaemi BipolarDokument10 SeitenGhaemi BipolarAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Bipolar Dos DosDokument9 SeitenBipolar Dos DosAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Tratamiento Trastorno Deficit AtencionDokument8 SeitenTratamiento Trastorno Deficit AtencionAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- What? Me Worry!?! What? Me Worry!?!Dokument7 SeitenWhat? Me Worry!?! What? Me Worry!?!KonkmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Electroencephalography (Eeg)Dokument31 SeitenElectroencephalography (Eeg)Nidhin Thomas100% (3)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Articulo Tdah AdultoDokument9 SeitenArticulo Tdah AdultoAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Tdah en Un AdultoDokument6 SeitenTdah en Un AdultoAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Bipolaridad Tratamiento y SolucionesDokument16 SeitenBipolaridad Tratamiento y SolucionesAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Efficacy Naltrexone Treatment Alcohol DependenceDokument8 SeitenEfficacy Naltrexone Treatment Alcohol DependenceAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Articulo Tdah AdultoDokument9 SeitenArticulo Tdah AdultoAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Anemia y Depresion Chen 2012Dokument3 SeitenAnemia y Depresion Chen 2012AlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Sleep Disorders QuestionnaireDokument13 SeitenSleep Disorders QuestionnaireAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Adhd AdultDokument13 SeitenAdhd AdultAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Escala Sobre DepresionDokument11 SeitenEscala Sobre DepresionAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Escala Sobre AnsiedadDokument9 SeitenEscala Sobre AnsiedadAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anemia y DepresionDokument7 SeitenAnemia y DepresionAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- La Regla de Los Tres para Trastorno BipolarDokument10 SeitenLa Regla de Los Tres para Trastorno BipolarAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Ddis DSM 5Dokument20 SeitenDdis DSM 5AlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Complicated Psychology of Revenge - Association For Psychological ScienceDokument3 SeitenThe Complicated Psychology of Revenge - Association For Psychological ScienceAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nature ConscineesssDokument16 SeitenNature ConscineesssAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Validacion de La Escala de Sintomas en Trastorno BorderlineDokument7 SeitenValidacion de La Escala de Sintomas en Trastorno BorderlineAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychiatric GeneticsDokument339 SeitenPsychiatric GeneticsAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trastornos Psiquiatricos en Pacientes de Cirugia BariatricaDokument7 SeitenTrastornos Psiquiatricos en Pacientes de Cirugia BariatricaAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Depresión y Ansiedad en Una Población de Pacientes Con Cirugía BariatricaDokument8 SeitenDepresión y Ansiedad en Una Población de Pacientes Con Cirugía BariatricaAlexisMolinaCampuzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Thesis 3Dokument26 SeitenThesis 3Gin ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- TOYOTA Project Marketing SurveyDokument27 SeitenTOYOTA Project Marketing SurveyMohammad Rafi100% (5)

- ResearchreviseDokument9 SeitenResearchreviseTyron Ellis Del RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Effective Forecasting On Business Growth, A Case of Businesses in Juba MarketDokument17 SeitenThe Impact of Effective Forecasting On Business Growth, A Case of Businesses in Juba MarketsegunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conflict Management Styles of Unit Heads of City Schools Division of Tayabas CityDokument22 SeitenConflict Management Styles of Unit Heads of City Schools Division of Tayabas Citydumai06Noch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Behavior in Relation To Insurance ProductsDokument52 SeitenConsumer Behavior in Relation To Insurance Productsprarthna100% (1)

- A Feasibility Study of Establishing A Dairy Shop in BataanDokument23 SeitenA Feasibility Study of Establishing A Dairy Shop in BataanPrecious AlteradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Significant Relationship Between Work Performance and Job Satisfaction in PhilippinesDokument11 SeitenThe Significant Relationship Between Work Performance and Job Satisfaction in PhilippinesPatrick Peligon TemploraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Microwave DesignDokument121 SeitenMicrowave DesignCj Llemos100% (1)

- Perceptions of Criminology Students On Identity Theft in Social Media 4Dokument29 SeitenPerceptions of Criminology Students On Identity Theft in Social Media 4Mariane GumbanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Strategy ProcessDokument34 SeitenThe Strategy ProcessOliver SalacanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Addie Designing MethodDokument6 SeitenAddie Designing MethodBrijesh ShuklaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study On Tax EvasionDokument2 SeitenCase Study On Tax EvasionNoel NicartNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tourism Development THESIS 1.Dokument56 SeitenTourism Development THESIS 1.Fatima ShahidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Plan Final Version (WIP) .Doc Change 5Dokument54 SeitenBusiness Plan Final Version (WIP) .Doc Change 5Hussain Chakera100% (1)

- Educational Management in The Light of Islamic Standards: British Journal of Education, Society & Behavioural ScienceDokument9 SeitenEducational Management in The Light of Islamic Standards: British Journal of Education, Society & Behavioural ScienceAbdallah SadurdeenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abanes The Factors Affecting The Budgeting Skills and Spending Behavior Among Senior High School Students of Thy Covenant Montessori School in S.Y. 2019 2020Dokument27 SeitenAbanes The Factors Affecting The Budgeting Skills and Spending Behavior Among Senior High School Students of Thy Covenant Montessori School in S.Y. 2019 2020Bjarne Lex Francis AgbonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reliance Industries Training PresentationDokument31 SeitenReliance Industries Training PresentationMahesh KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indahag National High School: Lesson Plan in Practical Research 2Dokument2 SeitenIndahag National High School: Lesson Plan in Practical Research 2Ruffa LNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment Details: U3: Research Techniques For The Creative Media IndustriesDokument4 SeitenAssignment Details: U3: Research Techniques For The Creative Media Industriesapi-432165820Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Action ResearchDokument5 SeitenSample Action ResearchIvy Rose RarelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Third Wave of The Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS3) - Strauss Et Al 2000Dokument88 SeitenThe Third Wave of The Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS3) - Strauss Et Al 2000dharendraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Research MethodsDokument16 SeitenBusiness Research MethodssyyyedsadiqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Encouraging Innovative Behavior: The Effects of Manager-Employee Relationship Quality and Public Service MotivationDokument36 SeitenEncouraging Innovative Behavior: The Effects of Manager-Employee Relationship Quality and Public Service MotivationNadya SafitriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Initial Survey Report of Nursery BusinessDokument5 SeitenInitial Survey Report of Nursery BusinessAsad Asad100% (2)

- SERVQUEL in Egypt BankDokument13 SeitenSERVQUEL in Egypt BankhannidrisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Retail Atmospherics in Attracting Customers: A Study of Retail Outlets of LucknowDokument6 SeitenImpact of Retail Atmospherics in Attracting Customers: A Study of Retail Outlets of LucknowkangkongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Computers in Industry: Stefano Perini, Rossella Luglietti, Maria Margoudi, Manuel Oliveira, Marco TaischDokument10 SeitenComputers in Industry: Stefano Perini, Rossella Luglietti, Maria Margoudi, Manuel Oliveira, Marco TaischMuhamad AlfajriNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 IDokument64 Seiten3 IPrincessMarieGomezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Survey QuestionsDokument4 SeitenSurvey QuestionsSamantha LynnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedVon EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (80)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismVon EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (5)

- Maktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistVon EverandMaktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (3)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionVon EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (2475)

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearVon EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (558)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentVon EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (4125)