Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

9220735

Hochgeladen von

Muhammed BarznjiCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

9220735

Hochgeladen von

Muhammed BarznjiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

American Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology

2014; 1(4): 56-61

Published online December 20, 2014 (http://www.aascit.org/journal/ajpp)

ISSN: 2375-3900

Medication errors in pediatric

hospitals

Darya Omed Nori1, Tavga Ahmed Aziz2,

Saad Abdulrahman Hussain3, *

1

Department of Pharmacy, Sulaimani Pediatric Teaching Hospital, Kurdistan, Iraq

Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medical Sciences,

University of Sulaimani, Kurdistan, Iraq

3

Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, College of Pharmacy, University of Baghdad,

Baghdad, Iraq

2

Email address

saad_alzaidi@yahoo.com (S. A. Hussain)

Keywords

Citation

Pediatrics,

Medication Errors,

Antibiotics,

Prescribing Practice

Darya Omed Nori, Tavga Ahmed Aziz, Saad Abdulrahman Hussain. Medication Errors in

Pediatric Hospitals. American Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology.

Vol. 1, No. 4, 2014, pp. 56-61.

Abstract

Received: November 28, 2014

Revised: December 08, 2014

Accepted: December 09, 2014

Background: Drugs are a dualistic therapeutic tool, they are intended to cure, prevent or

diagnose diseases, but improper use leads to patient morbidity or mortality. Aim: The

present study was designed to evaluate medication errors (MEs) in Sulaimani Pediatric

Hospital. Method: Prospective study was performed in Sulaimani Pediatric Teaching

Hospital, Sulaimani City, Kurdistan Region, through which the physician medication

orders for newly admitted patients from 6th February to 10th June 2013 were evaluated

for MEs. A standardized questionnaire (especially adopted for the present study) was

utilized to identify all expected types of MEs that appeared in the follow up sheets of

randomly selected pediatric patients (n=100), admitted to the hospital due to different

causes. Parents, usually mothers, answer some of the questions. 85% MEs were reported

during prescribing practice. Results: They involved medications include bronchodilators

45%, anti-emetics 33%, antibiotics 32%, and analgesics and antipyretics 29%. The most

frequently used antibiotics involved in the MEs were ceftriaxone 24%,

ampicillin+cloxacillin 12% followed by cefotaxime and amikacin. The highest

percentage of errors was 75% belonged to the use of teicoplanin followed by amikacin

60%. Conclusion: The percentages of MEs in Sulaimani Pediatric Hospital are very high,

and there is irrational use of antibiotics. Most of MEs are avoidable utilizing the roles

and activities of clinical pharmacists to provide maximum health care services.

1. Introduction

Drugs are a dualistic therapeutic tool, intended to cure, prevent or diagnose diseases,

but improper use can predispose to patient morbidity and even mortality (1). It is

important to understand the risk factors and causes of pediatric medication errors (MEs)

so that effective reduction strategies can be proposed. Individualized dosing is one of the

causes of pediatric MEs, where doses in the pediatric population are usually calculated

individually, based on the patients age, degree of prematurity in neonates, weight or

body surface area, and clinical condition. This may leads to increased opportunities for

dosing errors (2,3). Many evidences confirm that some healthcare professionals have

difficulty to calculate the correct dose (4-6). This might be complicated by the fact that

57

Darya Omed Nori et al.: Medication Errors in Pediatric Hospitals

many formulations are designed for use in adults, with few

drugs being commercially available in suitable dosage

forms (7), or more importantly, the correct strength for

children. Clinicians should not prescribe for children if they

are not familiar with the pediatric population, and/or the

drugs they are using (8,9). Good communication between

the hospital, the community pharmacy and the medical

practitioner is essential in order to maintain an appropriate

supply of the childs medicine (10). Creating a prescription

is an early step in medication use; therefore, reviewing

orders and prescriptions by pharmacists and nurses is

critical for detecting errors and preventing adverse impacts

on patients. Prescription errors occur at a rate of 3 to 20%

of all prescriptions in hospitalized pediatric patients, and

10.1% of children seen in emergency departments (11).

Accumulating studies suggest that pharmacist interventions

have major impact on reducing MEs in pediatric patients,

thus improving the quality and efficiency of care provided

(12). In traditional hospital practice most of the burden of

drug therapy decision-making falls on the physician.

However, studies have shown that physicians sometimes

make errors in prescribing drugs (13,14). While most errors

are harmless or are intercepted, some may result in adverse

drug events (ADEs). For hospitals with a system of

pediatric clinical pharmacists, the non-intercepted errors

represent the potential risk for patient harm, and would

ideally be targeted by the institution of additional

medication safety systems (computerized physician order

entry, barcoding, and automated dispensing devices) (15).

However, the pharmacists impact might be substantially

great, if he or she could provide input earlier at the time of

prescribing. It has been shown that pharmacist consultation

with physicians and others resulted in reduced drug coast,

provide continuity in individualized pharmaco-therapeutic

care, and serve an important educational function (16). A

recent study of pediatric MEs and ADEs has shown that

pediatric ward-based pharmacists could intercept 94% of

near misses, but this assumption has not yet been

adequately tested [17]. The present study was designed to

evaluate MEs in Sulaimani Pediatric Hospital.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This was a prospective study performed in Sulaimani

Pediatric Teaching Hospital, Sulaimani City, Kurdistan

Region. The physician medication orders for newly admitted

patients, during a period of four months (6th February to 10th

June, 2013), were evaluated for drugs prescribing errors. The

total capacity of Pediatric hospital was approximately 334

beds (including emergency and neonatal intensive care unit).

The cases were collected in three wards (excluding cases

from emergency and neonatal intensive care unit), which

represent approximately 61% (207 beds) of the hospital. A

standardized questionnaire, especially adopted for the present

study was utilized to identify all the expected types of MEs

appeared in the follow up sheets, which belongs to randomly

selected pediatric patients admitted to the hospital due to

different causes. Parents, usually mothers, answer some of

the questions.

2.2. Main Outcome Measures

The medication orders were hand-written, on daily bases

and whenever an additional order or change is requested, by

the authorized physicians, including rotators, permanents,

and consultants. Information on each patient profile including

age, weight, gender, residency, educational status, diagnosis

upon admission, reason and frequency of admission, any

reported allergies, and a complete medication profile for the

present hospitalization, were reviewed. All of the medication

orders were reported, reviewed and carefully assessed

according to the standard criteria globally followed

elsewhere. After collection of data, the types of prescribed

medication classes and the associated MEs were evaluated, in

addition to the types MEs associated with the prescription of

antibiotics.

3. Results

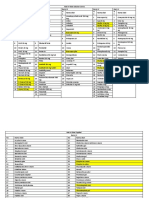

The data indicates that 73% of patients have information

about the orally taken medications and 23% have

information about parenterally administered medications.

Regarding their knowledge about the medication and

disease, only 10% have enough information (Table1).

Figure 1 shows that 55% of the evaluated case sheets

include clear diagnosis of the disease, while 45% of the

case sheets do not. Figure 2 shows that the most frequent

medication classes involved in this study were as follow:

32.4% antibiotics, 17% analgesics, 13.2% I.V. fluids, 9.3%

potassium

chloride,

8.8%

corticosteroids,

5.8%

antihistamines, 5.6% bronchodilators, 3.7% tonics and

vitamins, 2.2% and 2 % anxiolytics and anti-emetics,

respectively. In the current study, evaluation of 587

medication orders revealed the presence of 499 MEs (85%)

(Figure 3). Figure 4 shows the distribution of the selected

cases of pediatric patients according to the educational state

of their parents, in addition to the frequency of hospital

admission and having information about the medication and

diseases. The current study showed that the bronchodilators

represent the medication class with highest reported level of

errors (45%), followed by the antiemetics and antibiotics.

The data also showed that analgesics, antipyretics, and

potassium chloride represent the third level regarding the

reported MEs. Other medication classes involved in

reporting MEs are as follow: anxiolytics 15%,

corticosteroids, tonics and vitamins are 14%, antihistamines

and cough preparations 9%, and IV fluids 8% (Figure 5).

Regarding the errors during the prescription of antibiotics,

figure 6 shows the most frequently prescribed types of

antibiotics, and the percentage of error that occur with each

type.

American Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2014; 1(4): 56-61

58

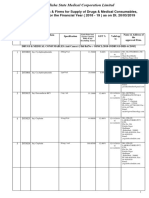

Table 1. The information regarding the route of administration of the

prescribed drugs and those related to the disease and type of medications

Rout of

administration

oral

Patient

information

73%

Parenteral

23%

Medication and Disease

No

Few

information information

24%

66%

Enough

information

10%

Table 2. The types of prescribing errors reported in the followed pediatric

patients

Type of Error

Omission

Delay in services

Prescription incomplete

Incorrect dose

Incorrect duration

Incorrect dosage form

Drug-drug interaction

Adverse reactions

Allergy and past history information

%

1%

2%

29%

33%

2%

2%

6%

4%

6%

Figure 3. Total Number of prescribing Errors reported in the case sheets

Figure 1. Information regarding diagnosis of the disease in the patients'

case sheets.

Figure 4. The educational statuses of the pediatric patients families, their

information about the disease and medications, frequency of admission and

percentages of medication errors

Figure 2. The classes of frequently prescribed medication that appeared in

case sheets of pediatric patients.

Figure 5. Incidence of medication errors according to the drug classes

involved

59

Darya Omed Nori et al.: Medication Errors in Pediatric Hospitals

Figure 6. Percentages of most frequently prescribed antibiotics and

percentage of errors involved with each type.

Figure 7. State of culture and sensitivity of prescribed antibiotics

4. Discussion

Hospitalized children are more susceptible to prescribing

errors and mistakes made during dosage calculation than

adults, because of their lower body weight and other

physiological characteristics (17). The data of the current

study revealed that 73% of parents have enough information

about the orally administered medications, while only 23%

have such information about parenterally administered

medications. This may be due to their educational status.

Additionally, most of parents had only primary level of

education. Another reason for such finding may be the

inactive role of ward pharmacists, or lack of communications

between the pharmacist and the parents, regarding patient

education about the proper use of medications. There is

evidence from projects, based on analysis of the types of

MEs, that improved communication could potentially reduce

medication-related errors (18,19). Pharmacists and nurses

should check the drug, the dose, patient identity and any

other relevant information before administering medicine.

When a query arises, as to whether the drug should be

administered, the patients or their parents in case of children

should be listened to attentively, and their questions should

be answered; the prescription should be double-checked with

the prescriber (20). Although the ward pharmacists routinely

checked all case sheets included in the present study, MEs

were not identified or corrected. Therefore, the main causes

behind these problems are the absence of appropriate role of

pediatric clinical pharmacist, shortage in number of clinical

pharmacists, work overload, and poor communication

between physician and pharmacists. Recently, a study done

by Fortescue et al. showed that monitoring MEs by a clinical

pharmacist may prevent 58% of all errors, and 72% of

potentially harmful errors; meanwhile, improving physicianpharmacist communication may prevent 47.4% of errors (18).

Other factors that contribute to these problems are children's

low body weight and other physiological characteristics,

which render them more vulnerable than adults to prescribing

errors during dosage calculation. Other factors include

decreased communication abilities of children, inability to

self-administer medications, and the high susceptibility of

young critically ill children to injury from medications,

particularly those with immature renal and hepatic systems

(21). Drug therapies are considered as major component of

pediatric management in health care settings like hospitals.

Effective medical treatment of a pediatric patient is based

upon accurate diagnosis and optimum course of therapy,

which usually involves a medication regimen. Infants and

children are among the most exposed population groups to

contact illnesses. At the same time, infancy and childhood are

periods of rapid growth and development. Most of these are

self-limiting (22) and often treated not only inappropriately,

but also resorting to polypharmacy (23,24). The result of the

current study shows that the most common classes of

medications involved are antibiotics (32.4%), followed by

antipyretics and analgesics (17%), then I.V. fluids (3.2%),

and to lesser extent potassium chloride, corticosteroids,

antihistamines, bronchodilators, tonics and vitamins,

anxiolytics and antiemetics. The percentage of prescribed

antibiotics in the present study is higher than other classes.

Many other studies support this finding, and concluded that

antibiotics are most commonly prescribed drugs to children,

followed by drugs for respiratory ailments or analgesics and

antipyretics (23,25). Other studies reported that 18.5-29% of

the medications used in pediatrics are antimicrobial agents

(26,27). It is important to consider the fact that only 4% of

prescribed antibiotics were prescribed depending on the

results of culture and sensitivity, while 79% were prescribed

without performing culture and sensitivity test. Antibiotics

can be used empirically without awaiting definite

identification of the causative organism after ordering

investigations aimed at making a microbiologically-based

diagnosis (if available and feasible). It is particularly

American Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2014; 1(4): 56-61

important to send cultures, diligently collected, before the

first dose of any antibiotic is administered except in sick

neonates or intoxicated child, where one cannot wait for

culture reports and need to start antibiotic urgently (28).

Overuse of antibiotics is known to cause drug resistance,

increased side effects and make the treatment expensive

(26,27). Furthermore, in a study conducted in USA, the most

common type of prescription drugs were bronchodilators for

children and central nervous system stimulants for

adolescents (26). The most common medication classes

detected during recording of errors in the present study were

bronchodilators, anti-emetics, antibiotics, antipyretic and

analgesics, respectively. These data are in tune with that

reported by Kaushal et al., where the most common drugs

involved in MEs are anti-infective agents, analgesics and

sedatives, electrolytes and fluids, and bronchodilators (17).

Al-Jeraisy et al., found that error rates are highest in

prescriptions for electrolytes (17.17%), antibiotics (13.72%)

and bronchodilators (12.97%) (29). Meanwhile, Folli et al.

reported that antibiotics are the class of drugs mostly

commonly responsible for dosing errors. Orders for

bronchodilators, analgesics, and fluid and electrolytes were

also frequently predispose to prescribing errors (15).

5. Conclusions

The percentages of MEs in Sulaimani Pediatric Hospital

are very high, and there is irrational use of antibiotics. Most

of MEs are avoidable utilizing the roles and activities of

clinical pharmacists to provide maximum health care services.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the University of Sulaimani and

Sulaimani Pediatric Hospital for supporting the project.

References

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M, (Eds.), To Err Is Human:

Building a Safer Health System. Committee on Quality of

Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine, Washington,

DC, National Academy Press, 1999.

Koren G, Barzilay Z, Greenwald M. Ten-fold errors in

administration of drug doses: a neglected iatrogenic disease in

pediatrics. Pediatrics 1986; 77:848-849.

Koren G, Haslam RH. Pediatric medication errors: predicting

and preventing ten-fold disasters. Journal of Clinical

Pharmacology 1994; 34:1043-1045.

Rowe C, Koren T, Koren G. Errors by pediatric residents in

calculating drug doses. Archive of Disease in Children 1998;

79:56-58.

Glover ML, Sussmane JB. Assessing pediatrics residents

mathematical skills for prescribing medication: a need for

improved training. Academic Medicine 2002; 77:1007-1010.

Gladstone J. Drug administration errors: a study into the

factors underlying the occurrence and reporting of drug errors

in a district general hospital. Journal of Advanced Nursing

60

1995; 22:628-637.

[7]

Yeung YW, Tuleu CL, Wong ICK. National study of

extemporaneous preparations in English paediatric hospital

pharmacies. Pediatric and Perinatal Drug Therapy 2004;

6:75-80.

[8]

Chappell K, Newman C. Potential tenfold drug overdoses on a

neonatal unit. Archive of Diseases in Children, Fetal and

Neonatal Education 2003; 89:F483-484.

[9]

Tan E, Cranswick NE, Rayner CR, et al. Dosing information

for paediatric patients: are they really therapeutic orphans?

Medical Journal Australia 2003; 179:195-198.

[10] Wong ICK, Basra N, Yeung V, et al. Supply problems of

unlicensed and off-label medicines after discharge. Archive of

Disease in Children 2006; 91:686-688.

[11] Lesar TS, Mitchell A, Sommo P. Medication safety in

critically ill children. Clinical Pediatrics and Emergency

Medicine 2006; 7:215-225.

[12] Korin G. Trend of medication errors in hospitalized children.

Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2002; 42:707-710.

[13] Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of adverse

drug events and potential adverse drug events implications of

prevention. Journal of American Medical Association 1995;

274:29-34.

[14] Leape LL, Bates DW, Cullen DJ, et al. Systemic analysis of

adverse drug events. Journal of American Medical Association

1995; 274:35-43.

[15] Folli HL, Poole RL, Benitz WE, Russo JC. Medication error

prevention by clinical pharmacists in two children's hospitals.

Pediatrics 1987; 79:718-722.

[16] Montazeri M, Cook DJ. Impact of clinical pharmacist in a

multi-disciplinary intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine

1994; 22:1044-1048.

[17] Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, et al. Medication errors

and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. Journal of

American Medical Association 2001; 285:2114-2120.

[18] Fortescue EB, Kaushal R, Landrigan CP, et al. Prioritizing

strategies for preventing medication errors and adverse drug

events in pediatric inpatients. Pediatrics 2003; 111:722-729.

[19] Stebbing C, Wong ICK, Kausha R, et al. The role of

communication in pediatric drug safety. Archive of Diseases in

Children 2007; 92:440-445.

[20] Wong ICK, Wong LYL, Cranswick NE. Minimizing

medication errors in children. Archive of Diseases in Children

2009; 94:161-164.

[21] Kaushal R, Jaggi T, Walsh K, Fortescue EB, Bates DW.

Pediatric medication errors. Ambulatory Pediatrics 2004;

4(1):73-81.

[22] Straand J, Rokstad K, Heggedal U. Drug prescribing for

children in general practice: A report from the More and

Romsdal prescription study. Acta Pediatrica 1998; 87:218-224.

[23] Sanz EJ, Bergman U, Dahlstorm M. Pediatric drug prescribing.

European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1989; 37:65-68.

[24] Ghai OP, Paul VK. Rational drug therapy in pediatric practice.

Indian Pediatrics 1988; 25:1095-1109.

61

Darya Omed Nori et al.: Medication Errors in Pediatric Hospitals

[25] Neubert A, et al. Databases for pediatric medicine research in

Europe:

assessment

and

critical

appraisal.

Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2008; 17:1155-1167.

[28] Yewale VN, Dharmapalan D. Promoting appropriate use of

drugs in children. International Journal of Pediatrics 2012;

10:9065-9070.

[26] Dimri S, Tiwari P, Basu S, Parmar VR. Drug use pattern in

children at a teaching hospital. Indian Pediatrics 2009;

46(2):165-167.

[29] Al-Jeraisy M, Alanazi MQ, Abolfotouh M. Medication

prescribing errors in a pediatric inpatient tertiary care setting

in Saudi Arabia. BMC Research Notes 2011; 4:294.

[27] Khaled A, Sami M, Majed I, Mostafa A. Antibiotic prescribing

in a pediatric emergency setting in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi

Medical Journal 2011; 32(2):197-198.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Dosage Calculations 3 Worksheet 1Dokument6 SeitenDosage Calculations 3 Worksheet 1Ayeza DuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10-TCT 2012fyughklDokument196 Seiten10-TCT 2012fyughklMuhammed BarznjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmacology Questions and AnswersDokument42 SeitenPharmacology Questions and AnswersAnnum BukhariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transdermal Delivery SystemsDokument58 SeitenTransdermal Delivery SystemsFazrul AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teach ManualDokument78 SeitenTeach ManualShouvik DebnathNoch keine Bewertungen

- DetailedapproaDokument65 SeitenDetailedapproaMuhammed BarznjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early MiscarriageretrjytkuyiulDokument6 SeitenEarly MiscarriageretrjytkuyiulMuhammed BarznjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Respiratory Examination: The Position of The PatientDokument24 SeitenRespiratory Examination: The Position of The PatientMuhammed Barznji100% (1)

- Local AnestheticsgfhgjhkjlkDokument3 SeitenLocal AnestheticsgfhgjhkjlkMuhammed BarznjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lung & Thorax Exams: Charlie Goldberg, M.D. Professor of Medicine, UCSD SOMDokument33 SeitenLung & Thorax Exams: Charlie Goldberg, M.D. Professor of Medicine, UCSD SOMMuhammed BarznjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Gestational Trophoblastic Disease?Dokument42 SeitenWhat Is Gestational Trophoblastic Disease?Muhammed BarznjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cranial Nerve Examination: OverviewDokument8 SeitenCranial Nerve Examination: OverviewMuhammed BarznjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Limb Length DiscrepancyDokument2 SeitenLimb Length DiscrepancyMuhammed BarznjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cerebellar ExaminationDokument1 SeiteCerebellar ExaminationMuhammed BarznjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crying - Dr. Shwan: Causes?!Dokument2 SeitenCrying - Dr. Shwan: Causes?!Muhammed BarznjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Respiratory Emergencies in PediatricsDokument49 SeitenRespiratory Emergencies in PediatricsMuhammed BarznjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statistics in Drug Research PDFDokument372 SeitenStatistics in Drug Research PDFpromaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Textbook of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics PDFDokument6 SeitenA Textbook of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics PDFMovie Box MoviesNoch keine Bewertungen

- DR, REDDY LABORATORIES LTD. (Pitch Book)Dokument8 SeitenDR, REDDY LABORATORIES LTD. (Pitch Book)Priya SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar Obat Ranap - MiraRevisiDokument6 SeitenDaftar Obat Ranap - MiraRevisiMiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prometric Mcqs Plus CaculationsDokument147 SeitenPrometric Mcqs Plus CaculationsShanaz KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Drug Discovery ProcessDokument58 SeitenEarly Drug Discovery ProcessFrietzyl Mae Generalao100% (1)

- Lecture 4 170824065306 PDFDokument19 SeitenLecture 4 170824065306 PDFSami SamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 4 - Case Study ReportDokument7 SeitenModule 4 - Case Study ReportAlbert BugasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Berno 2Dokument32 SeitenBerno 2Try AdipradanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap 3. Drug Utilization EvaluationDokument28 SeitenChap 3. Drug Utilization EvaluationAizaz AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Department of Pharmacology Class Routine-April, 2020 (3, 4, 5 & Bds-Semester) Jnims, Porompat ImphalDokument1 SeiteDepartment of Pharmacology Class Routine-April, 2020 (3, 4, 5 & Bds-Semester) Jnims, Porompat ImphalNeerajeigya ManoharNoch keine Bewertungen

- 909-Hazardous Drugs Table - EviqDokument9 Seiten909-Hazardous Drugs Table - EviqMd Al AminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Counter Transfer Vipin MishraDokument6 SeitenCounter Transfer Vipin Mishravipin mishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poisons PharmacistsDokument20 SeitenPoisons PharmacistsHenry SpencerNoch keine Bewertungen

- GSKDokument5 SeitenGSKHK KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabus IOM B.pharmaDokument56 SeitenSyllabus IOM B.pharmaks0259415Noch keine Bewertungen

- ScriptDokument4 SeitenScriptAlika HNoch keine Bewertungen

- Odisha Rate Contract For MedicinesDokument66 SeitenOdisha Rate Contract For MedicinesSahil KargwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- EMS Result 2Dokument2 SeitenEMS Result 2bhushanNoch keine Bewertungen

- List ABC TestDokument66 SeitenList ABC Testtiwa ramadanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MRM COLLEGE OF PHARMACY 5th Year ClerkshipDokument13 SeitenMRM COLLEGE OF PHARMACY 5th Year ClerkshipkushalNoch keine Bewertungen

- SeLnIkRaj - Ligand ScoutDokument26 SeitenSeLnIkRaj - Ligand ScoutselnikrajNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Molecular Principle in Drug Design: Dr. Rudi Hendra Sy. M.SC., AptDokument27 SeitenGeneral Molecular Principle in Drug Design: Dr. Rudi Hendra Sy. M.SC., AptRifqi Ahmad IrzamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmacology Course OutlineDokument2 SeitenPharmacology Course OutlineChinedu H. DuruNoch keine Bewertungen

- TetrabenazinaDokument23 SeitenTetrabenazinanieve2010Noch keine Bewertungen

- Paracetamol A Review of Three Routes of AdministrationDokument3 SeitenParacetamol A Review of Three Routes of AdministrationMohd MiqdamNoch keine Bewertungen