Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

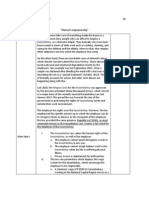

6 Jurisdiction, Powers

Hochgeladen von

gfvjgvjhgvOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

6 Jurisdiction, Powers

Hochgeladen von

gfvjgvjhgvCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

6 Jurisdiction, Powers

and Procedures of

the Court

Cheryl Loots

Gilbert Marcus

Page

6.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6--1

6.2 Jurisdiction under the interim Constitution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6--1

(a) The Constitutional Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6--1

(b) The Supreme Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6--3

(i) The Appellate Division . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6--4

(ii) Provincial and local divisions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6--4

(c) Other courts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6--7

(d) Interim relief . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--10

(e) Transitional provisions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--12

6.3 Powers of the courts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--15

(a) Validity of legislation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--16

(b) Constitutionality of executive or administrative act . . . . . . . . . . 6--16

(c) Constitutionality of a Bill . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--16

(d) Costs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--16

6.4 Procedure under the interim Constitution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--18A

(a) Procedure for dealing with issues beyond the jurisdiction of a court . 6--19

(i) Issues arising in the Supreme Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--19

(aa) A potentially decisive issue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--19

(bb) The exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court . . 6--21

(cc) The interests of justice . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--22

(ii) Issues arising in lower courts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--24

(b) Procedure in the Supreme Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--25

(c) Access to the Constitutional Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--25

[REVISION SERVICE 5, 1999] 6--i

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF SOUTH AFRICA

Page

(d) Referral of issues of public importance to the Constitutional Court . . 6--26

(e) Intervention by government . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--27

(f) Appeals from a decision of the Supreme Court . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--28

(g) Appeals from decisions of other courts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--29

(h) Review of the decisions of inferior courts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--29

6.5 Jurisdiction under the final Constitution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--30

(a) The Constitutional Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--31

(b) The Supreme Court of Appeal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--32

(c) The High Courts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--33

(d) The magistrates courts and other courts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--34

(e) The Labour Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--34A

6.6 Powers of the courts under the final Constitution . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--34A

(a) Costs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--34A

(b) Other powers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--34A

6.7 Procedure under the final Constitution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--35

(a) The inherent power of the Constitutional Court to regulate its own

process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--35

(b) Procedure for dealing with issues beyond the jurisdiction of a court . 6--36

(i) Issues arising in the superior courts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--36

(ii) Issues arising in the lower courts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--37

(c) Procedure in the High Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--38

(d) Direct access to the Consitutional Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--38

(e) Intervention by government . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--39

(f) Appeals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--39

(g) Review of decisions of inferior courts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--40

6.8 The application of the interim and final Constitutions to pending

proceedings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--40

(a) Proceedings pending on 4 February 1997 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--40

(b) Matters arising after 4 February 1997 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6--44

6--ii [REVISION SERVICE 5, 1999]

JURISDICTION, POWERS AND PROCEDURES OF THE COURT

6.1 INTRODUCTION

REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998

1The introduction of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act 200 of 1993 (the

interim Constitution (IC)) gave rise to a variety of jurisdictional problems. The first

concerned the competence of the courts to deal wih disputes which arose before 27 April

1994.1 The second problem was a function of the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional

Court to declare an Act of Parliament to be unconstitutional.2 It related to the procedural

requirements for submitting a dispute to the Constitutional Court.3 With the coming into

operation of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act 108 of 1996 (the final

Constitution (FC)) some of the old jurisdictional problems still persist and new ones have

been created.

Under the final Constitution the courts have been renamed and their jurisdiction altered.

What was formerly known as the Supreme Court is now known as the High Court and what

was formerly known as the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court is now known as the

Supreme Court of Appeal. All the superior courts now enjoy the jurisdiction to declare an

Act of Parliament to be unconstitutional. The final Constitution deals with the transition

from the interim Constitution. Proceedings which were pending when the final Constitu-

tion took effect on 4 February 1997 must be disposed of as if the new Constitution had not

been enacted, unless the interests of justice require otherwise. Accordingly the jurisdictional

and procedural requirements which pertained under the interim Constitution will continue

to be operative in relation to pending proceedings. This chapter therefore deals with

jurisdictional and procedural requirements under both the interim Constitution and the

final Constitution.

6.2 JURISDICTION UNDER THE INTERIM CONSTITUTION

(a) The Constitutional Court

The interim Constitution provides for the establishment of a Constitutional Court consisting

of a President and ten other judges.4 Jurisdiction is conferred upon the Constitutional Court

by IC s 98(2),5 which provides that it shall have jurisdiction in the Republic as the court of

final instance over all matters relating to the interpretation, protection and enforcement

of the provisions of the Constitution, including:

1

Section 241(8) of the interim Constitution was thought to cater for this problem. It was a provision, however,

which gave rise to intense litigation and, in the result, left certain questions unanswered. See below, 6.2(d).

2

The only exception to the exclusive jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court to declare an Act of Parliament to

be unconstitutional was the procedure created by s 101(6), in terms of which the parties could, by agreement, confer

jurisdiction upon a provincial or local division of the Supreme Court to hear matters falling outside their additional

jurisdiction, including the jurisdiction to declare an Act of Parliament to be unconstitutional.

3

The procedure for referring a dispute concerning the validity of an Act of Parliament from a provincial or local

division of the Supreme Court to the Constitutional Court was contained in s 102(1). It the first two years of its

existence the Constitutional Court devoted more time to this provision than any other. See below, 6.4(a).

4

Section 98(1). The President of the court is appointed in terms of s 97(2)(a). Section 99 provides for the

composition of the court and the appointment of judges.

5

The jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court derives solely from s 98. It has no inherent jurisdiction. Du Plessis

& others v De Klerk & another 1996 (3) SA 850 (CC), 1996 (5) BCLR 658 (CC) at para 52.

[REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998] 6--1

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF SOUTH AFRICA

(a) any alleged violation or threatened violation of any fundamental right entrenched in

Chapter 3 of the Constitution;

(b) any dispute over the constitutionality of any executive or administrative act or conduct

or any threatened executive or administrative act or conduct of any organ of state;

(c) any inquiry into the constitutionality of any law, including an Act of Parliament,

irrespective of whether such law was passed or made before or after the commencement

of the Constitution;

(d) any dispute over the constitutionality of any Bill before Parliament or a provincial

legislature;

(e) any dispute of a constitutional nature between organs of state at any level of

government;

(f) the determination of questions as to whether any matter falls within its jurisdiction;

and

(g) the determination of any other matters as may be entrusted to it by the Constitution or

any other law.

2 Section 98(3) provides that the Constitutional Court shall be the only court having

jurisdiction over a matter referred to in s 98(2), save where otherwise provided in ss 101(3)

and (6) and 103(1) and in an Act of Parliament.1 Reference to these sections and the relevant

Acts of Parliament2 reveals that the Constitutional Court has exclusive jurisdiction with

regard to an inquiry into the constitutionality of an Act of Parliament;3 a dispute over the

constitutionality of any Bill before Parliament; and a dispute of a constitutional nature

between organs of state at national level. A decision of the Constitutional Court shall bind

all persons and all legislative, executive and judicial organs of state.4

In Du Plessis v De Klerk5 Kentridge AJ concluded that the Constitutional Court had no

jurisdiction under s 98(2) to apply and to develop the common law and that s 35(3) did not

give it that jurisdiction.6 Thus the Appellate Division remains the court with ultimate

responsibility for the interpretation of statutes and the application and development of the

common law. The powers of the Constitutional Court in this respect are limited to an oversight

function. It must determine what the spirit, purport and objects of Chapter 3 are, and it must

1

Section 101(3) and (6) deal with the Supreme Courts jurisdiction to hear constitutional issues (see below,

6.2(b)). Section 103(1) provides that the jurisdiction of other courts shall be as prescribed by or under a law.

2

Section 110 of the Magistrates Courts Act 32 of 1944 is the only relevant provision at present. See below, 6.4.

3

In Zantsi v Council of State, Ciskei, & others 1995 (4) SA 615 (CC), 1995 (10) BCLR 1424 (CC) the

Constitutional Court confirmed that its exclusive jurisdiction covered all Acts of the South African Parliament,

irrespective of whether they were passed before or after 27 April 1994. The court a quo had suggested that the Acts

of Parliament contemplated by s 101(3) of the Constitution were only those passed by Parliament constituted in

accordance with the Constitution. On this basis the court had reached the conclusion that the Supreme Court has

jurisdiction to inquire into the validity of Acts passed by the South African Parliament prior to 27 April 1994.

4

Section 98(4).

5

1996 (3) SA 850 (CC), 1996 (5) BCLR 658 (CC) at paras 63--4. See also the judgment of Mahomed DP at

paras 85--7.

6

See also Shabalala v AG, Transvaal 1996 (1) SA 725 (CC), 1995 (12) BCLR 1593 (CC), 1995 (2) SACR 761

(CC) at para 9 and Gardener v Whitaker 1996 (4) SA 337 (CC), 1996 (6) BCLR 775 (CC) at para 16. Section 35(3)

provides that in the interpretation of any law and the application and development of the common law, a court shall

have due regard to the spirit, purport and objects of [the Bill of Rights]. The section is discussed below, Woolman

Application, 10.3(a)(v) and Kentridge & Spitz Interpretation 11.3(c).

6--2 [REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998]

JURISDICTION, POWERS AND PROCEDURES OF THE COURT

ensure that in the interpretation of laws and the application and development of the common

law other courts, including the Appellate Division, have taken due regard of the spirit, purport

and objects. The precise extent of this oversight function remains, as yet, uncertain.1 It will

become clear only once the approach of the court to the substantive meaning of s 35(3) has

been established. If, as Kentridge AJ and Mahomed DP stated in Du Plessis v De Klerk,2

there is little difference of substance between direct horizontal application of the Bill of

Rights to the private common law and indirect application through s 35(3), the oversight

function of the court with respect to s 35(3) ought closely to parallel the judicial review

function that it exercises with respect to s 33(2) over legislation. Where legislation unjusti-

fiably limits fundamental rights, the court declares it to be inconsistent with the Constitution,

but cannot rewrite it, for that is the task of Parliament. Similarly, where the common law

determines private rights in a manner which cannot be justified in terms of Chapter 3, it is

submitted that the court should declare it to be inconsistent with the Constitution, but not engage

in the task of reformulating it because that is the task of the Supreme Court. Thus a declaration

that a rule of the common private law is inconsistent with the Constitution should be followed

by the remission of the matter to the Supreme Court for the rule to be redeveloped with due

regard to the spirit, purport and objects of the Bill of Rights. In the course of remitting the

matter the Constitutional Court will give some guidelines to the Supreme Court of the range

within which any redeveloped rule must fall if it is to be consistent with the Constitution.3 If,

however, the rule as ultimately redeveloped by the Supreme Court remains inconsistent with

the Constitution, the process will have to be repeated.4

(b) The Supreme Court

3 he interim Constitution provides that there shall be a Supreme Court of South Africa,

T

consisting of an Appellate Division and such provincial or local divisions as may be

prescribed by law.5

1

See Du Plessis v De Klerk (supra) at paras 63 and 87 and Gardener v Whitaker (supra) at para 16.

2

Supra at paras 60 and 72--3 respectively.

3

An example of such guidelines is to be found in the order granted by the Constitutional Court in Shabalala v

AG, Transvaal 1996 (1) SA 725 (CC), 1995 (12) BCLR 1593 (CC), 1995 (2) SACR 761 (CC) at para 72. The case

dealt with the constitutionality of the common-law rules of state privilege as set out in R v Steyn 1954 (1) SA 324

(A). Although the case involved the direct application of the Constitution to the common law, Mahomed DP

emphasized at para 9 that it was not the task of the Constitutional Court, but that of the Supreme Court, to develop

new common-law rules of privilege to replace those which the Constitutional Court had declared to be inconsistent

with the Constitution.

4

This might appear cumbersome, but is no more cumbersome than the approach taken to legislation which limits

fundamental rights in a manner which cannot be justified in terms of s 33(1). The court leaves it to Parliament to

rewrite the legislation to remove the violation of the right. If the rewritten legislation does not address the

constitutional problem satisfactorily, the court will once more declare it to be inconsistent with the Constitution. It

will not, however, rewrite the legislation itself.

5

Section 101(1). This section is subject to ss 241 and 242 by virtue of an amendment effected by s 4(a) of the

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Third Amendment Act 13 of 1994. Section 241 provides for transitional

arrangements with regard to the judiciary. Section 242 requires the rationalization of court structures to be

undertaken as soon as possible after the Constitution comes into operation.

[REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998] 6--3

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF SOUTH AFRICA

(i) The Appellate Division

The Appellate Division is deprived of jurisdiction to hear constitutional issues by s 101(5),

which provides that it shall have no jurisdiction to adjudicate any matter within the

jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court. In Du Plessis v De Klerk,1 however, the Constitu-

tional Court held that s 101(5) did not affect the jurisdiction of the Appellate Division to

interpret laws and to apply and to develop the common law with due regard to the spirit,

purport and objects of the Bill of Rights, as required by s 35(3).2 Kentridge AJ reasoned that

a court in s 35(3) meant any court, including the Appellate Division. Section 101(5) did not

preclude this conclusion because the interpretation of law and the application and develop-

ment of the common law were not matters which fall within the jurisdiction of the

Constitutional Court in terms of s 98(2).3

4 Section 35(3) requires that binding pre-constitutional Appellate Division decisions may

have to be reconsidered in the light of the spirit, purport and objects of the Bill of Rights.4

There is a compelling argument that s 35(3) would, in appropriate cases, also require the

reconsideration of Appellate Division decisions made after the Constitution came into effect

but before the Constitutional Court judgment in Du Plessis v De Klerk was handed down.

Prior to Du Plessis v De Klerk the Appellate Division appears not to have regarded itself as

having any jurisdiction in terms of s 35(3) and at no stage did it endeavour to exercise such

jurisdiction.5 It would be anomalous if the doctrine of stare decisis meant that the failure of

the Appellate Division to exercise a jurisdiction which it did not know that it possessed should

act as a barrier to its exercise of that jurisdiction once it was clear that this was competent.

(ii) Provincial and local divisions

The provincial and local divisions of the Supreme Court6 have a constitutional jurisdiction

which extends beyond s 35(3). Section 101(2) declares that:

1

1996 (3) SA 850 (CC), 1996 (5) BCLR 658 (CC) per Kentridge AJ at paras 63--4 and per Mahomed DP at

paras 85--7.

2

The effect of s 35(3) is discussed more fully below, Woolman Application 10.3(a)(v) and Kentridge & Spitz

Interpretation 11.3(c).

3

The Constitutional Court retains an oversight function in respect of s 35(3). See 6.2(a) above.

4

Such reconsideration can be undertaken by provincial and local divisions of the Supreme Court. See, for

example, Gardener v Whitaker 1995 (2) SA 672 (E), 1994 (5) BCLR 19 (E) and Holomisa v Argus Newspapers Ltd

1996 (2) SA 588 (W). In both these cases the court exercised s 35(3) jurisdiction to depart from previously binding

Appellate Division decisions with respect to the common law of defamation.

5

See, for example, B v S 1995 (3) SA 571 (A), a case involving the claim of a father to access to his illegitimate

child. In assessing whether the common law should be developed to afford the father an automatic right of access

the Appellate Division made no mention of s 35(3).

6

There was some difference of judicial opinion as to whether the courts of the former TBVC states (Transkei,

Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei) are to be regarded as provincial and local divisions of the Supreme Court for

the purposes of the Constitution. In S v Majavu 1994 (4) SA 268 (Ck) at 291H--J it was held that the Ciskei General

Division fell within the category of a provincial or local division and was therefore endowed with additional

jurisdiction by s 101(3). In Sithole & others v Minister of Defence & another 1995 (1) SA 205 (Tk), 1994 (4) BCLR

68 (Tk), on the other hand, it was held that courts established in the former national states lack the additional

jurisdiction provided for in s 101(3). The issue has now been settled by the Constitution of the Republic of South

Africa Third Amendment Act 13 of 1994, which inserted s 241(1A) and (1B) into the Constitution. The effect of

these subsections is that the Supreme Courts of the former TBVC states and any General Divisions of such courts

are treated as provincial or local divisions of the Supreme Court for the purposes of the Constitution.

6--4 [REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998]

JURISDICTION, POWERS AND PROCEDURES OF THE COURT

Subject to this Constitution, the Supreme Court shall have the jurisdiction, including the inherent

jurisdiction, vested in the Supreme Court immediately before the commencement of this Constitu-

tion, and any further jurisdiction conferred upon it by this Constitution or by any law.

5 Section 101(3) confers jurisdiction on the provincial and local divisions of the Supreme

Court in respect of the following constitutional issues:

(a) any alleged violation or threatened violation of any fundamental right entrenched in

Chapter 3 of the Constitution;

(b) any dispute over the constitutionality of any executive or administrative act or conduct

or any threatened executive or administrative act or conduct of any organ of state;

(c) any inquiry into the constitutionality of any law applicable within its area of jurisdic-

tion, other than an Act of Parliament,1 irrespective of whether such law was passed or

made before or after the commencement of the Constitution;

(d) any dispute of a constitutional nature between local governments or between a local

and a provincial government;

(e) any dispute over the constitutionality of any Bill before a provincial legislature;

(f) the determination of questions as to whether any matter falls within its jurisdiction;

and

(g) the determination of any other matters as may be entrusted to it by an Act of Parliament.

Section 101(6) enables parties, by agreement, to confer jurisdiction upon a provincial or

local division to hear a matter falling outside this additional jurisdiction, provided that such

agreement may not confer jurisdiction in respect of an appeal against a decision of a

provincial or local division made in respect of a matter referred to in s 101(3).2 It seems

strange in principle that the parties should be able to confer jurisdiction with regard to

subject-matter upon a court. The Magistrates Courts Act3 enables parties to confer increased

value jurisdiction or territorial jurisdiction upon the court by agreement, but not subject-

matter jurisdiction.4 Where the legislature deprives a court of subject-matter jurisdiction it

usually has a good reason for doing so. In the case of the validity of Acts of Parliament, an

obvious reason for reserving jurisdiction to the Constitutional Court is that its pronounce-

ment of invalidity will have effect throughout the country, whereas that of a provincial or

local division would have effect only within its area of territorial jurisdiction, giving rise to

inconsistency in the law.

1

In Zantsi v Council of State, Ciskei, & others 1995 (4) SA 615 (CC), 1995 (10) BCLR 1424 (CC) the

Constitutional Court ruled that Acts of the TBVC legislatures were not Acts of Parliament within the meaning of

s 101(3) and thus fell within the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

2

Such appeals lie to the Constitutional Court: s 102(12). In S v Shangase & another 1994 (2) BCLR 42 (D) at

44F it was held that the word parties in s 101(6) includes an accused in criminal proceedings, provided that he is

legally represented and has been fully advised of his rights.

3

Act 32 of 1944.

4

See s 45.

[REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998] 6--5

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF SOUTH AFRICA

6 The Constitutional Court has repeatedly emphasized that the Supreme Court is obliged

to exercise the constitutional jurisdiction conferred upon it by s 101.1 In S v Zuma & others2

Kentridge AJ stated:

Even if a rapid resort to this court were convenient that would not relieve the judge from making

his own decision on a constitutional issue within his jurisdiction. The jurisdiction conferred on

judges of the provincial and local divisions of the Supreme Court under section 101(3) is not an

optional jurisdiction. The jurisdiction was conferred in order to be exercised.

The Supreme Court under the interim Constitution exercises the jurisdiction vested in the

Supreme Court of South Africa immediately before the commencement of that Constitution.

Because s 241 treats Supreme Courts of the former TBVC territories as provincial divisions

of the Supreme Court for jurisdictional purposes,3 the subject-matter jurisdiction of these

courts is now determined by the Supreme Court Act 59 of 1959 and not by the instruments

in terms of which they were established. Therefore a Full Bench of a TBVC Supreme Court

now has jurisdiction over criminal and civil appeals from superior court decisions within its

area of jurisdiction.4

Subsections (1A) and (1B) of s 241 deal with subject-matter jurisdiction. Section 241

does not affect the reach of the civil and criminal process of the Supreme Court.5 In terms

of s 2296 this continues to be governed by the different statutes applying to the South African

and TBVC Supreme Courts. These statutes did not have extra-territorial force. Thus the civil

and criminal process of the South African courts did not run to the TBVC states7 and the

civil and criminal process of the TBVC courts ran only within their respective areas of

1

See S v Vermaas; S v Du Plessis 1995 (3) SA 292 (CC), 1995 (7) BCLR 851 (CC), in which the Constitutional

Court overruled S v Lombard en n ander 1994 (3) SA 776 (T), 1994 (2) SACR 104 (T) and S v Vermaas 1994 (4)

BCLR 18 (T), which had held that s 102(2) allows a judge of the Supreme Court to refrain from deciding a matter

within the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and to refer it to the Constitutional Court. See also S v Mhlungu &

others 1995 (7) BCLR 793 (CC) at para 1 of the judgment of Mahomed J and at paras 55--8 of the judgment of

Kentridge AJ; S v Mbatha 1996 (2) SA 464 (CC), 1996 (3) BCLR 293 (CC), 1996 (1) SACR 371 (CC) at para 28;

Bernstein & others v Bester & others NNO 1996 (2) SA 751 (CC), 1996 (4) BCLR 449 (CC) at para 2; Nel v Le

Roux NO & others 1996 (3) SA 562 (CC), 1996 (4) BCLR 592 (CC) at para 26; Brink v Kitshoff NO 1996 (4) SA

197 (CC), 1996 (6) BCLR 752 (CC) at para 7.

2

1995 (2) SA 642 (CC) at 649D--F (para 10), 1995 (4) BCLR 401 (SA).

3

See s 241(1A)(b) and (1B).

4

See the obiter comments of Comrie J in Steelchrome (Pty) Ltd v Jacobs & others 1995 (8) BCLR 944 (B) at

948A--950B. In terms of s 241(1A)(a) the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of South Africa also now has

appellate jurisdiction over TBVC superior court decisions. The Appellate Divisions of the TBVC Supreme Courts

were abolished by s 241(1)(a).

5

Any doubt in this regard is removed by s 241(1A)(b), which provides that the jurisdiction of the courts in

question shall be exercised in respect of the area of jurisdiction for which they were established. The point was

raised, but not decided, in Stadsraad van Lichtenburg en n ander v Premier van die Noordwes Provinsie en n ander

1995 (8) BCLR 971 (B).

6

The section states that all laws which immediately before the commencement of this Constitution were in

force in any area which forms part of the national territory, shall continue in force in such area, subject to any repeal

or amendment of such laws by a competent authority. In the Western Cape Legislature case the Constitutional

Court said that this section provides a constitutional foundation for the continuation of the old laws after the

coming into force of the Constitution, but pointed out that the continuity given by s 229 is applicable only to the

areas in which such laws were in force prior to the commencement of the Constitution: Executive Council, Western

Cape Legislature, & others v President of the Republic of South Africa & others 1995 (4) SA 877 (CC), 1995 (10)

BCLR 1289 (CC) at para 87.

7

See, for example, S v Wellem 1993 (2) SACR 18 (E).

6--6 [REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998]

JURISDICTION, POWERS AND PROCEDURES OF THE COURT

territorial jurisdiction. No legislation has yet been drafted to rationalize the South African

and TBVC Supreme Court Acts and Criminal Procedure Acts. The anomalous result is that

an order of a division of the Supreme Court in what was previously South Africa cannot be

executed in parts of the national territory which previously formed part of the TBVC states,

and an order of a Supreme Court in what was previously a TBVC state cannot be executed

in any part of the national territory which did not form part of the relevant state. It is clear

that this state of affairs should be rectified by legislation as soon as possible.1

(c) Other courts

I7C s 103(1) provides that the establishment, jurisdiction, composition and functioning of all

other courts shall, subject to ss 241 and 242,2 be as prescribed by or under a law. The interim

Constitution does not confer any jurisdiction to determine issues of a constitutional nature

upon courts other than the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court, and it seems clear

that the original drafters of the Constitution did not intend other courts to have such

jurisdiction. In response to criticism of the lack of constitutional jurisdiction on the part of

the magistrates courts, the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Third Amendment

Act 13 of 1994 effected certain amendments which contemplate other courts having juris-

diction to determine constitutional issues.3

Section 103(2), (3) and (4) originally directed other courts before which the constitu-

tionality of any law was challenged either to assume the validity of such law or, if the

presiding officer was of the opinion that it was in the interest of justice to do so, to postpone

the proceedings to enable the challenge to be taken on application to the Supreme Court.

Section 103(2) has now been amended, with the effect that the aforesaid two options should

be pursued only where the court does not have the competency to inquire into the validity of

such a law or provision.4 The magistrates courts do have the competency to inquire into the

validity of certain subordinate legislation. Section 110 of the Magistrates Courts Act 32 of

1944 confers jurisdiction upon magistrates courts to pronounce upon the validity of any

1

With respect to matters of criminal procedure in all courts and civil procedure in the magistrates courts, the

situation will be regularized by the proclamation of the Justice Laws Rationalization Act 18 of 1996. The Act was

passed on 10 April 1996, but had not been proclaimed at the time of writing (31 August 1996). Section 2(1) of the

Act, read with Schedule I, extends the operation of inter alia the Criminal Procedure Act 56 of 1955, the Criminal

Procedure Act 51 of 1977 and the Magistrates Courts Act 32 of 1944 to cover the entire national territory. Section 3,

read with Schedule II, repeals the TBVC criminal procedure legislation and magistrates courts legislation which

was hitherto in force. However, the Act does not rationalize the existing laws relating to the Supreme Courts of

South Africa and the TBVC territories. So the limited reach of the civil process of the different divisions of the

Supreme Courts is unaffected by the Act. It appears that a decision was taken to postpone the rationalization of

legislation relating to the Supreme Court pending the investigations of the Hoexter Commission of Inquiry into the

Rationalization of the Provincial and Local Divisions of the Supreme Court (see para 6 of the Memorandum on

the Objects of the Justice Laws Rationalization Bill, 1996, Justice Laws Rationalization Bill, No B2B-96, p 102).

2

The phrase subject to sections 241 and 242 was inserted by s 4 of the Constitution of the Republic of South

Africa Third Amendment Act 13 of 1994. Section 241 deals with transitional arrangements. Section 242 provides

for the rationalization of court structures.

3

Sections 3 and 5(b) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Third Amendment Act 13 of 1994.

4

Section 103(2) as amended by s 5(b) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Third Amendment

Act 13 of 1994.

[REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998] 6--7

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF SOUTH AFRICA

statutory regulation, order or by-law.1 This would qualify as a law conferring jurisdiction

upon a court, as contemplated by s 103(1).

8 In order to enable magistrates courts or other courts to assume jurisdiction in respect of

constitutional issues conferred upon them by legislation it was also necessary to amend

IC s 98(3). Previously s 98(3) provided that the Constitutional Court would be the only court

having jurisdiction over constitutional matters except where such jurisdiction was conferred

on the Supreme Court by s 101(3) and (6). The exception has now been amended to include

reference to jurisdiction conferred upon other courts as provided by s 103(1) and in terms of

an Act of Parliament.2 No Act of Parliament has been enacted which expressly empowers

the magistrates courts or any other court to hear constitutional matters.

In Qozeleni v Minister of Law and Order & another3 it was held that s 103(2) and (3),

which require a magistrate to assume the validity of a law or provision or allow such issue

to be referred to the Supreme Court, apply only to statutory enactments, and do not prevent

a magistrate from applying the provisions of the Constitution in the exercise of his ordinary

substantive jurisdiction. Froneman J, Kroon J concurring, drew a distinction between a claim

for relief which was beyond the jurisdiction of the court and the application by the court of

the law in deciding a matter which was within its jurisdiction. He said:

Prior to the commencement of the new Constitution, lower courts, such as the magistrates courts,

did not have powers of review in respect of unlawful administrative action. They nevertheless had

to apply the existing law of the land when exercising their normal substantive jurisdiction and, if

this entailed disregarding administrative action found to be unlawful in the course of, for example,

an action for damages, they were entitled and compelled to do so, at least in this Division (Majola

v Ibhayi City Council 1990 (3) SA 540E at 534E--544G).

The court expressed the view that it would be inconceivable that the provisions of Chapter 3 of

the interim Constitution, which were meant to safeguard the rights of citizens, should not be

applied in the courts where the majority of people would have their initial and only contact.4

In Bate v Regional Magistrate, Randburg, & another5 Stegmann J held that the decision

in the Qozeleni case could not be reconciled with IC s 98(3), the effect of which was that

the magistrates courts had no jurisdiction to adjudicate upon any alleged violation or

threatened violation of any fundamental right entrenched in Chapter 3.6 In this case

the applicant, who had been charged with attempted murder in a regional court, applied to

the magistrate for an order that the prosecution be dismissed and/or that the state be refused

the opportunity to proceed with the prosecution. The basis of the application was that the

accused had been denied the right, which he had in terms of IC s 25(3)(a), to a trial within

a reasonable time after having been charged. The magistrate held that he had no jurisdiction

to hear the application. On review, counsel for the applicant and the respondent agreed,

apparently relying on the Qozeleni case,7 that the magistrate had erred in declining to assume

jurisdiction. Stegmann J disagreed, referring to IC s 7(4)(a), which provided that, where an

1

Section 110 provides that a magistrates court shall not be competent to pronounce upon the validity of

provincial legislation or a statutory proclamation of the State President.

2

Section 3 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Third Amendment Act 13 of 1994.

3

1994 (3) SA 625 (E) at 635D--638C. See also Da Silva Mendes & another v Kitching & another 1995 (12)

BCLR 1672 (E), 1995 (2) SACR 634 (E); Municipality of the City of Port Elizabeth v Prut NO & another 1996 (3)

BCLR 379 (SE).

4 5

At 637E. 1996 (7) BCLR 974 (W).

6 7

At 986C--E. At 985C--D.

6--8 [REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998]

JURISDICTION, POWERS AND PROCEDURES OF THE COURT

infringement of a right was alleged, application could be made to a competent court for

relief. He found that, in terms of IC s 98(3) and s 101(3), the Supreme Court was the only

competent court from which such relief could be claimed. It is submitted that the decision

of Stegmann J was correct, but that his criticism of the judgment in the Qozeleni case was

wrong, because he did not take into account that the defendant in that matter did not apply

for relief consequent upon an infringement of a constitutional right, but simply requested the

court to make a procedural ruling in line with his constitutional right.

9 The same mistake was made by a Full Bench of the Eastern Cape Provincial Division in

Port Elizabeth Municipality v Prut NO & another.1 The background facts in this case were

that the applicant municipality had issued a summons against the first and second respondents

in a magistrates court claiming payment of amounts owing by them in respect of rates. In

response to an application for summary judgment the respondents raised the defence that, in

breach of their constitutional right to equality, they had been unfairly discriminated against

because the municipality had failed to write off their debt, whereas it had written off similar

debts owed by ratepayers who lived in the formerly black townships. In consequence of this

defence the proceedings were stayed by agreement between the parties pending the outcome

of an application to declare, inter alia, that the municipalitys conduct did not constitute unfair

discrimination. The judge who heard that application held that the granting of relief to the

applicant would, in effect, decide the issues which, in terms of the affidavit filed by the

respondents in the summary judgment application, the magistrate would have to decide in

the action pending in the lower court. He held that relief should not be granted if the

magistrate was competent to decide on the issues involved and, applying the Qozeleni case,

concluded that the magistrate was competent to adjudicate upon the issues raised by the

respondent. In an appeal against that judgment the Full Bench held that the judge should

have dealt with the merits of the application and referred the matter back to him. The Full

Bench was correct in doing this, because a magistrates court is not competent to grant an

order declaring that conduct does not constitute an infringement of a constitutional right, but,

unfortunately, in coming to its decision, it held that the judgment of the court in the Qozeleni

case was incorect. This is wrong because in the Qozeleni case no application had been made

for relief consequent upon an alleged infringement of a constitutional right.

It is submitted that Froneman J was indeed correct when, in the Qozeleni case, he held

that the interim Constitution did not prevent a magistrate from applying its provisions in the

exercise of his ordinary substantive jurisdiction. In the Prut case the Full Bench of the Eastern

Cape Provincial Division held that the Qozeleni case was incorrect in so far as it was

inconsistent with its decision that magistrates courts are not competent to deal with an

alleged violation or threatened violation of a constitutionally guaranteed right.2 The court

concluded its judgment, however, by holding that the mere fact that a magistrates court has

no power to pronounce upon the constitutional matters referred to in IC s 98(2) did not mean

that it did not have power to apply the Constitution. The court held that the contrary is indeed

the case as there is no doubt that it is the duty of magistrates courts to ensure that

constitutionally guaranteed rights are observed in the proceedings conducted before them.3

1

1996 (4) SA 318 (E) at 326G--329D.

2

At 328E--H.

3

At 329B--C.

[REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998] 6--9

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF SOUTH AFRICA

In the light of this statement it is submitted that there is no inconsistency between the

Qozeleni case and the Prut case. In the Prut case the magistrate would have had jurisdiction

to consider the defence raised in response to the summary judgment application, but once

the plaintiff wanted a declaratory order to the effect that its conduct was not unconstitutional,

the matter had to be determined by the Supreme Court. In the Qozeleni case the magistrate

was simply ensuring that the proceedings before him were being conducted in accordance

with the Constitution. This is entirely in line with the dictum of the Constitutional Court in

S v Zuma & others,1 in which Kentridge AJ said that all courts hearing criminal trials were

to conduct such trials in accordance with the Constitution.

It is important to draw a distinction between matters in which the court is requested

to grant relief consequent upon an alleged infringement or threatened infringement of

constitutionally guaranteed rights, and matters in which it is simply required to apply the

provisions of the Constitution in order to determine a matter before it in respct of which it

has jurisdiction. It is submitted that in the former case a magistrates court is not a competent

court, as referred to in IC s 7(4)(a), but that in the latter case it is competent. On this basis

it is submitted that the decision in Walker v Stadsraad van Pretoria,2 in which it was held

that a magistrate had no jurisdiction to decide a matter in which a defence of unequal and

discriminatory treatment was raised, is wrong. The issue of the jurisdiction of the magistrates

courts remains unresolved.

(d) Interim relief

10 interim Constitution initially did not expressly empower the Supreme Court to grant

The

interim relief pending determination by the Constitutional Court of an issue which is beyond

the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.3 This gave rise to problems during the period after the

Constitution had come into operation but before the Constitutional Court had been

established. In a number of matters parties who wished to challenge the validity of an Act

of Parliament applied to the Supreme Court for interim relief pending a determination of

the validity issue by the Constitutional Court. The question which arose in these cases

was whether the Supreme Court had jurisdiction to grant such relief. The Cape4 and

1

1995 (2) SA 642 (CC) at 625D.

2

1997 (4) SA 189 (T), 1997 (3) BCLR 416 (T). In S v Lawrence; S v Negal; S v Solberg 1997 (4) SA 1176 (CC),

1997 (10) BCLR 1348 (CC) the Constitutional Court gave consideration to the question of the appropriate court to

receive evidence on the constitutionality of a statutory provision. In the course of this discussion Chaskalson P

referred with approval to Walker v Stadsraad van Pretoria (at para 15n19) but in the context of the receipt of evidence

in the magistrates court on a constitutional issue beyond the jurisdiction of the magistrates court. Save for this

reference, no consideration was given to the question of whether or not the magistrates court ought to have exercised

jurisdiction on the merits of the matter before it.

3

Section 101(7) now addresses this issue.

4

Wehmeyer v Lane NO & others 1994 (4) SA 441 (C) at 448H; S v Sixaxeni 1994 (3) SA 733 (C) at 736F--738A;

but see contra Japaco Investments (Pty) Ltd & others v The Minister of Justice & others 1995 (1) BCLR 113 (C),

in which Wehmeyer v Lane NO & others was held to have been wrongly decided and was overruled. In Stevens v

Jonker & another 1994 (3) SA 806 (C) interim relief was granted without the issue as to whether the court had

jurisdiction to grant such relief being raised.

6--10 [REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998]

JURISDICTION, POWERS AND PROCEDURES OF THE COURT

Eastern Cape courts1 and a Full Bench of the Witwatersrand Local Division2 held that the fact

that the Constitution deprives the Supreme Court of jurisdiction to inquire into the validity

of an Act of Parliament does not derogate from the Supreme Courts inherent jurisdiction to

grant interim relief to prevent the infringement of a fundamental right guaranteed in terms

of IC Chapter 3. The Transvaal,3 Northern Cape4 and Natal5 courts decided that they did not

have such jurisdiction. The basis of these decisions was that it was not possible to grant such

relief without considering and inquiring into the constitutionality of the statute and that the

Supreme Court had no jurisdiction to embark upon such an inquiry since the Constitutional

Court has exclusive jurisdiction with regard to any inquiry into the validity of an Act of

Parliament.6

11 The matter was resolved by the insertion of IC s 101(7),7 which grants provincial and

local divisions of the Supreme Court jurisdiction to grant an interim interdict or similar

relief, pending the determination by the [Constitutional] Court of any matter referred to in

section 98(2) of the Constitution, notwithstanding the fact that such interdict or relief might

have the effect of suspending or otherwise interfering with the application of the provisions

of an Act of Parliament.

It seems that there will be very limited direct access to the Constitutional Court since

the rules8 provide for such access only in exceptional circumstances. Where a challenge

to the validity of legislation is the only issue in a matter it will, in the ordinary course, be

necessary to bring an application to the Supreme Court as a first step, requesting that court

to refer the matter to the Constitutional Court in terms of s 101(2).9 It is inevitable that the

requirement of a preliminary application will give rise to the need for interim relief in many

cases. IC s 101(7) gives the Supreme Court the power to grant such interim relief.

1

Matiso v Commanding Officer, Port Elizabeth Prison, & another 1994 (3) SA 899 (E) at 902J--903B.

2

Ferreira v Levin NO & others 1995 (2) SA 813 (W), overruling Rudolph & another v Commissioner for Inland

Revenue & others NNO 1994 (3) SA 771 (W). In Ferreira v Levin NO & others the court recognized a new test to

be applied in applications for interim interdicts involving constitutional issues. Heher J, relying on American

Cyanamid Co v Ethicon Ltd [1975] 1 All ER 504 (HL), 2 WLR 316, AC 396, held that in such applications interim

relief should be granted where an applicant can show that there is a serious question to be tried in respect of the

validity of the legislation. See below, Klaaren Judicial Remedies 9.3(i).

3

De Kock & another v Prokeur-Generaal, Transvaal 1994 (3) SA 785 (T); Podlas v Cohen NO & others 1994

(4) SA 662 (T) at 671G--672F.

4

Schoeman v Die Balju vir die Landdroshof, Vryburg, en andere 1995 (2) BCLR 192 (NC).

5

Bux v Officer Commanding, Pietermaritzburg Prison, & others 1994 (4) SA 562 (N).

6

Bux v Officer Commanding, Pietermaritzburg Prison, & others (supra) at 565G.

7

Section 101(7) was inserted into the Constitution by s 3 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa

Second Amendment Act 44 of 1995. Prior to Act 44 of 1995 the provisions of s 101(7) had been contained within

s 16 of the Constitutional Court Complementary Act 13 of 1995, which was enacted to solve the problem of interim

relief.

8

Rule 17(1) of the Rules of the Constitutional Court published in GN R5 GG 16204 of 6 January 1995 (Reg Gaz

5450). See the discussion of rule 17(1) below, Chaskalson & Loots Court Rules and Practice Directives 7.3(b).

9

It is obviously envisaged that there may be proceedings in which the only issue arising is within the exclusive

jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court because s 102(17) provides that in such circumstances a refusal on the part

of the provincial or local division to refer such issue to the Constitutional Court shall be appealable to the

Constitutional Court. See Brink v Kitshoff NO 1996 (4) SA 197 (CC), 1996 (6) BCLR 752 (CC) at para 6.

[REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998] 6--11

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF SOUTH AFRICA

(e) Transitional provisions

Section 241 of the interim Constitution contains provisions concerning the transitional

arrangements with regard to courts, the judiciary and Attorneys-General. The courts existing

before the commencement of the Constitution are deemed to have been constituted in terms

of the Constitution, or the laws in force after its commencement, and continue to function in

accordance with the applicable laws until changed by a competent authority.1 Judicial officers

and Attorneys-General continue in office subject to the terms and conditions which applied

to their service prior to the commencement of the Constitution until changed by a competent

authority.2 The laws and other measures which immediately before the commencement of

the Constitution regulated the jurisdiction of courts of law, court procedures, the power and

authority of judicial officers, and all other matters pertaining to the establishment and

functioning of courts of law shall continue in force subject to any amendment or repeal

thereof by a competent authority.3

12 A provision which gave rise to some interpretation difficulties was s 241(8).4 The section

states:

All proceedings which before the commencement of this Constitution were pending before any

court of law, including any tribunal or reviewing authority established by or under any law,

exercising jurisdiction in accordance with the law then in force, shall be dealt with as if this

Constitution had not been passed: Provided that if an appeal in such proceedings is noted or review

proceedings with regard thereto are instituted after such commencement such proceedings shall be

brought before the court having jurisdiction under this Constitution.

It was argued in a number of Supreme Court cases that the effect of this provision is that

the interim Constitution has no application to any cases which were pending at the time of

its commencement. The Appellate Division, when faced with this argument, held that the

section was capable of more than one interpretation, but declined to express an opinion on

the correct interpretation, leaving it to the Constitutional Court to decide the issue.5 Some courts

accepted the argument,6 but others held that the intention of the drafters of the subsection

was simply to make provision for the continued territorial jurisdiction of the courts in pending

proceedings.7 A third interpretation was that the subsection limits the application of

procedural rights but not of substantive rights,8 while a fourth interpretation held that the

1

Section 241(1).

2

Section 241(2)--(6).

3

Section 241(10).

4

When the interpretation of s 241(8) finally came before the Constitutional Court in S v Mhlungu & others 1995

(3) SA 867 (CC), 1995 (7) BCLR 793 (CC), Kriegler J observed at para 86 that this issue had been considered by

many courts and commented that it would hardly be an exaggeration to say that the cases produced as many answers

as there were judgments.

5

S v Makwanyane en n ander 1994 (3) SA 868 (A) at 873D.

6

S v Lombard en n ander 1994 (3) SA 776 (T) at 782H--783F; S v Vermaas 1994 (4) BCLR 18 (T) at 62C--64D;

S v Coetzee & others 1994 (4) BCLR 58 (W); Mulaudzi & others v Chairman, Implementation Committee, & others

1994 (4) BCLR 97 (V). In S v Saib 1994 (4) SA 554 (D) at 560F--J the court accepted this interpretation, which was

accepted as a correct assumption in S v Ndima & others 1994 (4) SA 626 (D) at 631J.

7

Qozeleni v Minister of Law and Order & another 1994 (3) SA 625 (E) at 638D--640A, 1994 (1) BCLR 75 (E);

S v Sixaxeni 1994 (3) SA 733 (C) at 736F--737E; S v Smith & another 1994 (3) SA 887 (E) at 892D--F; S v Majavu

1994 (4) SA 268 (Ck) at 292E; S v Shuma & another 1994 (4) SA 583 (E) at 589G--590A.

8

S v Williams and Five Similar Cases 1994 (4) SA 126 (C) at 136F--138G, 1994 (2) BCLR 135 (D).

6--12 [REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998]

JURISDICTION, POWERS AND PROCEDURES OF THE COURT

section applied only to the particular proceedings within a case which were pending

immediately before the Constitution came into effect.1

When the meaning of IC s 241(8) came before the Constitutional Court in S v Mhlungu

& others2 the court divided. A minority held that the wording of s 241(8) unambiguously

demanded that the interim Constitution could have no application to cases which were

pending when it came into effect.3 The majority disagreed. All of the majority judges sought

to avoid an interpetation of s 241(8) which denied persons the protection of constitutional

rights simply because the proceedings in which those rights were invoked had commenced

before 27 April 1994.4 All of the majority judges found that the language of s 241(8) was

flexible enough not to require such an interpretation. Mohamed J, in whose judgment

Langa J, Madala J, Mokgoro J and ORegan J concurred, held that s 241(8) had no bearing

on the substantive law which was to be applied in proceedings; its function was simply to

preclude an attack on the authority of the courts to continue dealing with proceedings which

were pending before the commencement of the interim Constitution. This function was

necessary because s 241(1) provided for existing courts to exercise jurisdiction in cases

commencing after 27 April 1994, but did not address the authority of courts to continue to

hear cases which were pending when the interim Constitution came into operation.5

Kriegler J agreed that subsec (8) of s 241 did not relate to the law to be applied by a court,

but held that the authority of courts to continue dealing with pending proceedings was

adequately provided for by s 241 in subsecs (1)--(3) and (10). He concluded that s 241(8)

related not to a question of authority but rather to the more mundane question of the forum

in which cases pending on 27 April 1994 would be heard:

13 The subsection is concerned with the administrative channelling, handling and hierarchical

disposition of cases that were on the rolls of courts of the old South Africa . . . In the context,

I suggest, there can be little doubt that the subsection simply and only means that the tribunal having

jurisdiction under the old order has to deal with a pending case.6

Sachs J held that the plain meaning of s 241(8) related to the substantive law which was

to be applied in pending proceedings. This plain meaning set up a clear tension between

s 241(8) and IC Chapter 3, a tension which should be resolved purposefully by reading s 241(8)

subject to Chapter 3. Such a reading would preserve the functional core of s 241(8), which

was to provide for continuity in the administration of justice whilst causing the minimum

disturbance to fundamental rights enshrined in Chapter 3.7 Thus, while there was no majority

of judges which agreed on a precise meaning of s 241(8), a majority did concur in the

conclusion that s 241(8) does not preclude a litigant from invoking fundamental rights in a

trial which was pending on 27 April 1994, and this can be accepted as a ratio decidendi of

the court in Mhlungu.

1

Shabalala & others v Attorney-General of the Transvaal & others 1995 (1) SA 608 (T), 1994 (6) BCLR 85 (T);

Jurgens v The Editor, Sunday Times Newspaper, & another 1995 (1) BCLR 97 (W).

2

1995 (3) SA 867 (CC), 1995 (7) BCLR 793 (CC).

3

See the dissenting judgment of Kentridge AJ, in which Chaskalson P, Didcott J and Ackermann J concurred.

4

See, for example, paras 7--9 of the judgment of Mahomed J, paras 91, 92 and 100 of the judgment of Kriegler J,

paras 102 and 134 of the judgment of Sachs J.

5

See in particular paras 21--3 of the judgment of Mahomed J.

6

Judgment of Kriegler J at para 95.

7

See in particular paras 116 and 130 of the judgment of Sachs J.

[REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998] 6--13

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF SOUTH AFRICA

A number of important additional issues relating to the temporal reach of the Constitution

were addressed obiter by the majority judges. Mahomed J and Sachs J emphasized that the

interim Constitution did not have any application in respect of decisions taken before it came

into effect. Thus trials which were completed before 27 April 1994 could not be re-opened

for the purposes of raising constitutional points.1 Similarly, even in trials pending at the

commencement of the interim Constitution no constitutional challenge could be made to a

decision which had been taken prior to the commencement of the Constitution.2 Mahomed J

also stated that constitutional issues could not be raised on appeal unless those particular

issues had been decided by the trial court after the commencement of the interim Constitu-

tion. This was because an appeal inherently contains the complaint that the court a quo had

erred in terms of the law which was then of application to it and not in terms of a law which

subsequently came into operation.3

14 Several passages in the majority and minority judgments in Mhlungu appeared to conflate

the issue of whether the interim Constitution applied in proceedings which were pending on

27 April 1994 with the related, but different, issue of whether the interim Constitution applied

with retrospective effect.4 As a result, Mhlungu was widely assumed to have decided that

the interim Constitution applied retrospectively.5 In Du Plessis v De Klerk,6 however, the

Constitutional Court clarified that this was not the case. Kentridge AJ declared that

the Constitution does not turn conduct which was unlawful before it came into force into

lawful conduct. It does not enact that as at a date prior to its coming into force the law shall

be taken to have been that which it was not.7 Mahomed J confirmed that the legal validity

of acts must be determined by the law in force at the time that they were performed and that

the interim Constitution would not, in the usual course of events, affect the legal status of

1

See para 39 of the judgment of Mahomed J and paras 131 and 132 of the judgment of Sachs J.

2

See para 39 of the judgment of Mahomed J and paras 131 and 132 of the judgment of Sachs J. Cf the judgment

of Kriegler J at paras 98 and 99, where it is stated that a litigant in proceedings which were pending on 27 April

1994 has a right to the reconsideration of interlocutory orders made in those proceedings prior to the commencement

of the Constitution. The order given in Mhlungu seems to be more consistent with the judgment of Kriegler J than

with the judgments of Mahomed J and Sachs J. The order invalidates any application of section 217(1)(b)(ii) of

the Criminal Procedure Act, 1977 in any criminal trial, irrespective of whether it commenced before, on or after

27 April 1994, and in which the final verdict was or may be given after 27 April 1994. The order focuses on the

date of conclusion of criminal trials and not on the date of judicial decisions on the admissibility of confessions. In

so doing it invalidates judicial decisions on the admissibility of confessions which were taken prior to 27 April 1994

where these decisions were taken in a trial in which a final verdict had not been delivered on 27 April 1994. The

logic of the judgments of Mahomed J and Sachs J would suggest that such decisions should not have been affected

by the declaration of invalidity of s 217(1)(b)(ii).

3

Judgment of Mahomed J at para 41. Kriegler J and Sachs J did not address this issue. The minority judges

clearly believed that if s 241(8) did not preclude reliance on the Constitution in pending proceedings, it would not

preclude reliance on the Constitution in appeals from decisions taken prior to 27 April 1994. See para 83 of the

judgment of Kentridge AJ.

4

See, for example, the judgment of Kentridge AJ at para 68 and the judgment of Mahomed J at paras 38 and 46.

It was only the judgment of Kriegler J which distinguished clearly between the two issues (at para 99).

5

See, for example, the judgments of Cameron J and Froneman J respectively in Holomisa v Argus Ltd 1996 (2)

SA 588 (W) at 598G--J and S v Melani 1996 (2) BCLR 174 (E) at 184E--G.

6

1996 (3) SA 850 (CC), 1996 (5) BCLR 658 (CC). See also Key v Attorney-General & another 1996 (4) SA 187

(CC), 1996 (6) BCLR 788 (CC) at paras 3--6; Rudolph & another v Commissioner for Inland Revenue 1996 (4) SA

552 (CC) at para 15.

7

At para 20.

6--14 [REVISION SERVICE 2, 1998]

JURISDICTION, POWERS AND PROCEDURES OF THE COURT

acts performed prior to its commencement.1 Thus it is not ordinarily open to a litigant to rely

on the interim Constitution to found a cause of action or a defence in respect of events which

took place prior to 27 April 1994. The Constitutional Court did, however, leave open the

possibility that, where rights vested prior to 27 April 1994 were abhorrent to the values of

the interim Constitution, it might refuse to enforce them. It is clear, however, that it is only

in extreme cases that the court will apply this exception to the principle that the interim

Constitution has no retrospective operation.2

REVISION SERVICE 3, 1998

15 The decision in Du Plessis v De Klerk on the non-retrospectivity of the interim Constitu-

tion is limited to cases involving the direct application of the Constitution. The question

remains whether developments of the common law in accordance with IC s 35(3) take place

with retrospective effect. As was pointed out by Kentridge AJ in Du Plessis v De Klerk,3 the

ordinary development of the common law does take place with retrospective effect. Where

a judgment changes a common-law rule as it has hitherto been understood, the law maintains

a fiction that the new rule has not been changed by the court, but has merely been found.

Kentridge AJ raised the possibility that the ordinary rule of retrospective development of the

common law may have to be reconsidered in the context of changes brought about by

the Constitution, which itself does not apply retrospectively.

It is submitted that in cases involving IC s 35(3) there is no reason to depart from the

ordinary common-law rule of retrospective development. The principal objection to retro-

spective development of the common law is that it impairs existing legal rights. However,

this objection ignores the nature of the rights which are impaired. The common law changes

only to keep in step with legal policy. So any rights which are affected by such changes are

rights which are inimical to prevailing legal policy and thus not deserving of protection. A

right which is detrimentally affected by the development of the common law in accordance

with IC s 35(3) is, by definition, a right which depends on aspects of a discredited old legal

order and one which is incompatible with the new legal order based on fundamental human

rights. It would be most anomalous if the need to protect such rights should, in the face of

the ordinary common-law practice, be privileged over competing claims founded on the

spirit, purport and objects of the Bill of Rights.

6.3 POWERS OF THE COURTS4

The interim Constitution confers certain specific powers on the Constitutional Court with

regard to legislation or administrative acts found to be unconstitutional.5 The same powers

1

At para 68.

2

Kentridge AJ suggested at para 20 that a court might refuse to enforce such rights on the grounds that to do

so would be contrary to public policy. Mahomed J alluded to the possibility of exercising the courts jurisdiction

under s 98(6) to invalidate something which was not unlawful prior to the commencement of the Constitution.

(Section 98(6) is discussed below, Klaaren Judicial Remedies 9.5.)

3

At paras 65--6. It is for the Supreme Court of Appeal to decide whether IC s 35(3) or FC s 39(2) can be invoked

in cases where the cause of action arose before the Constitutions were in force. See Amod v Multilateral Motor

Vehicle Accidents Fund 1998 (10) BCLR 1207 (CC) at para 23

4

Many of the issues canvassed in this section are discussed in more detail below, Klaaren Judicial

Remedies ch 9.

5

Section 98(5), (6), (7), (8), and (9).

[REVISION SERVICE 3, 1998] 6--15

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF SOUTH AFRICA

are made applicable to the provincial and local divisions of the Supreme Court.1 There are

no similar provisions in respect of other courts.

(a) Validity of legislation

With regard to validity of legislation, a court finding that any law or provision thereof is

inconsistent with the Constitution shall declare such law invalid to the extent of its inconsis-

tency.2 A proviso follows to the effect that the court may, in the interest of justice and good

government, require Parliament or any other competent authority, within a period specified

by the court, to correct the defect in the law or provision, which shall then remain in force

pending correction or the expiry of the period so specified.3

16 The effect of a declaration of invalidity differs depending upon whether the relevant

law or provision existed at the commencement of the interim Constitution or was passed after

such commencement.4 The declared invalidity of a law which was in existence when the

interim Constitution commenced will not automatically invalidate anything done or permit-

ted in terms thereof before such declaration became effective.5 Where a law passed after the

commencement of the Constitution is declared invalid, everything done or permitted in terms

thereof is ordinarily invalidated.6 These prescribed effects are subject to any specific order

which a court may make in the interest of justice and good government.7

(b) Constitutionality of executive or administrative act

In the event of a court declaring an executive or administrative act or conduct of an organ of

state to be unconstitutional, it may order the relevant organ of state to refrain from such act

or conduct or, subject to such conditions and within such time as may be specified by it, to

correct such act or conduct in accordance with the Constitution.8

(c) Constitutionality of a Bill

A court may exercise its jurisdiction to determine a dispute over the constitutionality of any

Bill before Parliament or a provincial legislature only at the request of the Speaker of the

National Assembly, the President of the Senate, or the Speaker of a provincial legislature,

who shall make such a request to the court upon receipt of a petition by at least one-third of

the members of the relevant legislative body requiring him or her to do so.9

(d) Costs

With regard to costs, it is provided that the court may make such order as it may deem just

and equitable in the circumstances.10 It accordingly seems that neither the Constitutional

Court nor the Supreme Court, when deciding constitutional issues, is bound by the usual rule

1 2

Section 101(4). Section 98(5).

3 4

Proviso contained in s 98(5). Section 98(6).

5

Section 98(6)(a). The section is discussed below, Klaaren Judicial Remedies 9.5.

6 7

Section 98(6)(b). Section 98(6).

8

Section 98(7).

9

Section 98(9). The section is discussed above, Klaaren & Chaskalson National Government 3.1(d).

10

Section 98(8).

6--16 [REVISION SERVICE 3, 1998]

JURISDICTION, POWERS AND PROCEDURES OF THE COURT

that costs follow the outcome of the proceedings. This is important because the threat of an

adverse order of costs may serve as a substantial deterrent to many potential litigants. This

would be particularly unfortunate in the early stages of constitutional litigation, where

virtually every case is in the nature of a test case.1

REVISION SERVICE 5, 1999

17 It is instructive to refer to s 17(12)(a) of the Labour Relations Act 28 of 1956, which

empowers the Industrial Court to make an order as to costs according to the requirements

of the law and to fairness. In National Union of Mineworkers v East Rand Gold and Uranium

Co Ltd 2 the Appellate Division, in enunciating the considerations to be taken into account

when awarding costs in terms of this section, held that the general rule of our law that, in the

absence of special circumstances, costs follow the event is a relevant consideration, but will

yield where considerations of fairness require it. A consideration of fairness which the court

indicated should be taken into account was that parties, particularly individuals, should not

be discouraged from approaching the court and consideration should be given to avoiding

their being so discouraged, especially where there was a genuine dispute and the approach

to the court was not unreasonable.3

The Constitutional Courts most extensive discussion of the matter of costs came in

Ferreira v Levin NO & others (2), where the parties were ordered to pay their own costs.

According to Ackermann Js judgment, the flexible approach to costs developed by the

Supreme Court offered a starting point. If the need arises, the rules may have to be

substantially adapted; this should, however, be done on a case by case basis.4 Ackermann J

formulated the Supreme Courts approach as follows:

[It] proceeds from two basic principles, the first being that the award of costs, unless expressly

otherwise enacted, is in the discretion of the presiding judicial officer and the second that

the successful party should, as a general rule, have his or her costs. Even this second principle is

subject to the first. Without attempting either comprehensiveness or complete analytical accuracy,

depriving successful parties of their costs can depend on circumstances such as, for example, the

conduct of parties, the conduct of their legal representatives, whether a party achieves technical

success only, the nature of the litigants, and the nature of proceedings.5

In Ferreira the applicants were only partially successful with respect to one of the five

matters referred. This did not meet the threshold of successful in substance to award costs

to the applicants, according to Ackermann J. Further factors against awarding the applicants

1

In Ferreira v Levin NO & others (2) 1996 (2) SA 621 (CC), 1996 (4) BCLR 441 (CC) Ackermann J referred

at para 10 to the possible chilling effect that an adverse order as to costs would have on private individuals invoking

their constitutional rights as a very important policy issue which deserves anxious consideration, but left its

consideration to the appropriate case and occasion. See also Ex parte Gauteng Provincial Legislature: In re

Dispute Concerning the Constitutionality of Certain Provisions of the School Education Bill, 1995 (Gauteng) 1996

(3) SA 165 (CC), 1996 (4) BCLR 537 (CC), where the Constitutional Court held that the usual Supreme Court rule

of the losing party paying costs was not its general rule in petitions concerning the constitutionality of bills brought

to the court under s 98(9). Mahomed DP stated at para 36: A litigant seeking to test the constitutionality of a statute

usually seeks to ventilate an important issue of constitutional principle. Such persons should not be discouraged

from doing so by the risk of having to pay the costs of their adversaries, if the court takes a view which is different

from the view taken by the petitioner. Compare, however, Du Plessis & others v De Klerk & another 1996 (3) SA 850

(CC), 1996 (5) BCLR 658 (CC) at para 149, where Kriegler J suggests that constitutional litigants who proceed on

the basis of private interest as opposed to public motive should expect to be mulcted in costs if they are unsuccessful.

2 3

1992 (1) SA 700 (A) at 738F--740A. At 739B--C.

4

1996 (2) SA 621 (CC), 1996 (4) BCLR 441 (CC) at para 3.

5

Ferreira v Levin NO & others (2) (supra) at para 3.

[REVISION SERVICE 5, 1999] 6--17

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF SOUTH AFRICA

costs were that the applicants had not been obliged to come to the Constitutional Court for

the relief requested and that, as the referral had accordingly been improper, the Constitutional

Court had heard the matter only by way of direct access as an indulgence.1 With respect

to the respondents, the court began from the premise that they were successful in opposing

the applicants relief, but noted that the respondents had not opposed the referrals from the

Supreme Court. The court indicated that respondents should oppose inappropriate referrals

at the time when they are sought; they should not sit back and raise their opposition for the

first time in this court after the referral has been made.2

18 Where counsel appears at the request of the court it is not customary to make an order

for costs against the losing party. Similarly, the intervention of an amicus curiae does not

ordinarily result in an order for costs either for or against the amicus.3

Where the issues raised are genuine constitutional questions which raised matters of

broad concern and where the litigation was not spurious or frivolous, lack of success should

not attract an adverse order of costs.4

In constitutional proceedings arising out of a criminal matter, and where it is alleged that

the state breached an accuseds constitutional right to a fair trial, an adverse order of costs

will not ordinarily be appropriate where the complaint is genuine and relates to a point of

substance.5

Where a court of first instance has made a punitive order of costs and where the

Constitutional Court refuses an appeal to set aside that order, it does not follow that a similar

order (of punitive costs) should be made on appeal.6

1

At para 7.

2

At para 9. See also Nel v Le Roux NO & others 1996 (2) SA 562 (CC), 1996 (4) BCLR 592 (CC) at para 26;

Key v Attorney-General & another 1996 (4) SA 187 (CC), 1996 (6) BCLR 788 (CC); Bernstein & others v Bester

& others NNO 1996 (2) SA 751 (CC), 1996 (4) BCLR 449 (CC) at para 124.

3

Minister of Justice v Ntuli 1997 (3) SA 772 (CC), 1997 (6) BCLR 677 (CC) at para 43.

4

African National Congress & another v Minister of Local Government and Housing, KwaZulu, & others 1998

(4) SA 1 (CC), 1998 (4) BCLR 399 (CC) at para 34. See also Oranje Vrystaatse Vereniging van Staatsondersteunde