Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

LWBK836 Ch152 p1617-1621

Hochgeladen von

metasoniko81Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

LWBK836 Ch152 p1617-1621

Hochgeladen von

metasoniko81Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

CHAPTER

152 Kene Ugokwe

Edward C. Benzel

Cerebrospinal Fluid Fistula

and Pseudomeningocele

Spinal pseudomeningoceles and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fis- radiation. The same authors also reported a 43% incidence of

tulas are caused by similar mechanisms. A pseudomeningocele pseudomeningocele and a 13% incidence of CSF fistula in

is defined as a postoperative extravasated collection of extra- patients who underwent surgical release of a tethered spinal

dural CSF that communicates with the subarachnoid space cord.

through a breach in the dura mater and arachnoid. A pseudo-

meningocele may, however, develop into a CSF fistula, which

occurs when the extradural CSF communicates with another PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

cavity or if a direct communication to the outside exists. Dural

breaches that lead to CSF fistulas and pseudomeningoceles The primary cause of a pseudomeningocele or a postoperative

may also be expected to lead to increased perioperative mor- cutaneous CSF fistula is a persistent iatrogenic dural violation.

bidity, prolonged hospitalization, and possible reoperation to This may be incidentally discovered. It may be inadvertently

repair the leak. In patients who present with symptomatic created during surgery. In intradural tumor surgery, a duro-

pseudomeningoceles and CSF fistulas, a trial of nonoperative tomy is intentionally created to access the tumor. As discussed

management may be warranted. It is, however, important to earlier, majority of the dural tears that lead to pseudomeningo-

note that treatment strategies should be tailored to each indi- celes and CSF fistulas are iatrogenic but traumatic and con-

vidual patient and operative repair should occasionally be genital causes are occasionally identified.1,2,4 Other causes of

undertaken without delay. Factors that affect treatment choice CSF leak include lumbar punctures, dural puncture during

include size, location, timing, and symptoms. Small leaks may myelography, and dural puncture during placement of an epi-

heal spontaneously without sequelae or with nonoperative dural catheter. When a dural breach is recognized, CSF leakage

measures such as CSF diversion via a lumbar drain or place- may persist as a result of inadequate repair of the initial dural

ment of an epidural blood patch. violation, especially in difficult to reach areas such as in the

lateral gutters and in the ventral dura mater.

Cutaneous CSF fistulas occur in the immediate postopera-

INCIDENCE tive period when CSF tracks from the site of dural breach,

through the wound, to the skin surface. The CSF is usually

Spinal CSF fistulas and pseudomeningoceles are a common under low pressure and travels slowly. A pseudomeningocele

complication of spine surgery and the majority of them are iat- forms when the CSF travels slowly into the soft tissue, without

rogenic as a result of spine surgery. In the lumbar spine, there evidence of external drainage. In some situations, the dura may

is a reported incidence of CSF fistula of between 0.3% and be violated while the arachnoid remains intact, leading to the

13%.10,14 Oppel et al18 reported the incidence of dural tears to arachnoid herniating through the dura and the arachnoid

be 5.9% in a study of 3038 operations in which the dural tears lined sac becoming the pseudomeningocele. Teplick et al23

occurred during bone removal or dural sac and nerve root have suggested that when the intact arachnoid herniates

retraction. Schumacher et al21 reported the incidence of through the dura, it is more likely for the communication to

pseudomeningoceles to be less than 0.1% in 3000 patients who remain open, whereas when the arachnoid is breached along

had undergone a lumbar discectomy. It is difficult to determine with the dura, the communication will often close. Although

the true incidence of pseudomeningoceles following incidental feasible, this is not proven.

durotomies because many cases are asymptomatic. In certain Entrapment of nerve roots in the pseudomeningocele may

patient populations, the incidence of CSF wound complica- lead to radiculopathy and may become a barrier to dural heal-

tions is higher. These populations include patients with lamine- ing.8 The majority of dural tears heal spontaneously, but large

ctomy for spinal dysraphism and patients with a history of prior defects are unlikely to follow this course. Some factors that con-

spinal irradiation. Zide et al25,26 reported a 43% incidence of tribute to poor healing of dural tears include radiation, infec-

CSF fistula or pseudomeningocele after surgery in patients with tion, nutritional deficits, steroids, scar tissue, poor overlying

intramedullary spinal cord neoplasia previously treated with soft tissue coverage, and elevated CSF pressure.

1617

LWBK836_Ch152_p1617-1621.indd 1617 8/26/11 2:15:43 PM

1618 Section XIV Complications

CLINICAL FEATURES strate the level of communication with the thecal sac, as well as

any spinal cord compression or nerve root entrapment that

Majority of pseudomeningoceles are asymptomatic but some may exist.9 Myelographic studies are useful in elucidating trau-

may present with back pain, radicular pain, posture-related ma-induced nerve root pseudomeningoceles. These appear as

headache, nausea and vomiting, photophobia, meningismus, unilateral lesions that vary in size with irregular contours.2

or other signs of meningitis. Cervical and thoracic pseudo- Delayed computed tomographic myelography is useful in

meningoceles are more easily palpable than lumbar ones, but detecting a slow-filling pseudomeningocele13 (Fig. 152.2). Ret-

occasionally, lumbar collections may be identifiable in the sub- rograde radionuclide myelography has been used to detect

cutaneous tissue. Cutaneous CSF fistulas are often diagnosed slow, intermittent leaks after lumbar puncture,7 traumatic

by simple inspection of the wound. Light yellow to clear drain- injury,15 and pleural CSF fistulas.12

age from the wound, which is augmented by the Valsalva

maneuver, or associated with a postural headache, is usually

indicative of a CSF fistula. The drainage may be tested for B2 TREATMENT

transferrin, which is not present in sweat or serous fluid, and

detection of B2 transferrin, which is indicative of a CSF.20 B2 As with any surgical procedure, preparation and meticulous

transferrin is a protein isoform arising by the action of cerebral planning is imperative. The occurrence of iatrogenic pseudo-

neuraminidase. It is found only in the central nervous system. meningoceles and CSF fistulas cannot be eliminated com-

The disadvantage to this test is related to the fact that it may pletely, but their incidence can be reduced with attention paid

take up to 5 days for results to be obtained. to detail and careful bone and scar removal. Careful review of

Postural headaches are worse when the patient is in the preoperative imaging studies may also help detect any bone

upright position and improve or resolve when the patient is in anomalies or defects that may be congenital or a result of prior

the recumbent position. The headaches occur as a result of surgery. The dura mater should be carefully freed laterally, via

altered CSF dynamics (e.g., low CSF pressure) with CSF loss meticulous dissection, prior to bone removal with a Kerrison

through the fistula exceeding CSF production. punch. High-speed drills should be used in a lateral, to and fro,

sweeping manner so that a slip will not necessarily result in a

dural laceration. It is also important to ensure that exposed

IMAGING STUDIES dura is covered with a cottonoid during drilling in order to

decrease the chance of the drill-induced dural laceration. If a

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomo- breach in the dura does occur, it should be closed in a water-

graphic scans are routinely used to elucidate CSF fistula tracts tight primary fashion. It may be necessary to remove more

or pseudomeningoceles.14 MRI, however, is the diagnostic study bone than initially planned in order to expedite efficient and

of choice because of its ability to visualize soft tissue. With MRI, effective repair of the dural laceration.

a pseudomeningocele typically reveals low-signal intensity on

T1-weighted images and high-signal intensity on T2-weighted CONSERVATIVE THERAPY

images, as illustrated in Figure 152.1. Since the pseudomenin-

gocele contains CSF, it is not surprising that its signal character- The initial treatment of postoperative CSF fistulas has ranged

istics on MRI are consistent with CSF. It is also important to from conservative measures to immediate surgical repair.

note that both contrast and noncontrast images should be The treatment choice depends on various factors, including

obtained to rule out an infectious process. MRI may demon- size, symptoms, and the presence or absence of infection

A

B

Figure 152.1. (A) T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing a lumbar

pseudomeningocele. (B) T1-weighted axial MRI scan showing a lumbar pseudomeningocele.

LWBK836_Ch152_p1617-1621.indd 1618 8/26/11 2:15:43 PM

Chapter 152 Cerebrospinal Fluid Fistula and Pseudomeningocele 1619

Figure 152.2. (A) Sagittal postmyelogram computed tomo-

A graphic (CT) scan showing a lumbar pseudomeningocele. (B) Axial

postmyelogram CT scan showing a lumbar pseudomeningocele.

(Fig. 152.3). For a small CSF fistula in a mildly symptomatic Asymptomatic pseudomeningoceles can be followed clini-

patient without evidence of infection, a trial of bed rest, over- cally. If they become symptomatic, surgery should be consid-

sewing of the wound,24 percutaneous injection of an epidural ered but if the symptoms constitute just mild pain without neu-

blood patch,16 or closed subarachnoid drainage3,6 may be suc- rologic deficit, compressive garments and abdominal binders

cessful. A trial of lumbar drainage for approximately 3 to may be trialed. If they develop into CSF cutaneous fistulas, they

5 days, during which 10 to 15 mL/day of CSF is drained, is a may be treated in the way previously described for CSF fistulas.

reasonable first choice as a conservative strategy. It is important

to note that lumbar drainage is not necessarily a benign proce-

dure. As an invasive procedure, it carries with it the risk of sev- SURGICAL TREATMENT

eral complications, including spinal headaches (60%), infection

including meningitis (2.5%), discitis (5%), wound infection Surgical repair of dural lacerations and breaches is the defini-

(2.5%), and transient nerve root irritation and recurrence.22 tive treatment for CSF fistulas and pseudomeningoceles. Such

Closed CSF drainage is often effective. It is reported to elimi- should be instituted when conservative measures have failed or

nate cutaneous fistulas in 90% to 100% of cases.11,17,22 A percu- in situations in which conservative measures are expected to

taneous epidural blood patch has also been used to treat fail. Surgical treatment should be considered first-line therapy

postoperative CSF fistulas. Such strategies, however, are associ- for patients with profuse leakage of CSF. In patients with

ated with a paucity of literature that substantiates their utility.16 impaired CSF absorption, CSF shunting should be undertaken

With such a procedure, approximately 10 to 25 mL of fresh first, since any primary repair strategy for a dural defect under

autologous blood is injected into the epidural space near the such circumstances will usually fail. Once it is determined that

dural breach. The blood, theoretically, forms an occlusive clot surgical repair will be undertaken, adequate preoperative imag-

over the breach site.16 ing should be obtained to determine the level of the dural

breach unless the site of leakage is obvious from the history.

Also, in patients with wound breakdown, spinal dysraphism,

CSF Fistula/Pseudomeningocele and poor nutritional status, a preoperative plastic surgery con-

sult may be warranted. Intraoperatively, a generous skin inci-

sion should be employed. Oftentimes, this involves lengthening

Asymptomatic Symptomatic with Symptomatic the prior skin incision. Once the pseudomeningocele is identi-

without infection infection without infection fied and entered, it is explored and followed to the durotomy

site (Fig. 152.4). The durotomy site should be protected with a

cottonoid and must be completely exposed. This may require

Conservative Immediate If symptoms are

therapy including primary mild, consider extensive bone removal but this must be done before attempt-

bed rest, blood surgical conservative ing to repair the durotomy. Any visible nerve roots should be

patch, oversewing repair with therapy but with freed and reduced into the dura and the durotomy should be

the wound, and wound neurologic deficits, carefully inspected to ensure that there is no evidence of spinal

lumbar drainage washout consider surgery cord strangulation. The durotomy should be repaired under

microscopic magnification and illumination and a No. 4-0 to

Figure 152.3. Cerebrospinal fluid fistula/pseudomeningocele 7-0 nonabsorbable suture on a taper or reverse cutting, half

treatment algorithm. circle needle is usually used. Whenever possible, the dura

LWBK836_Ch152_p1617-1621.indd 1619 8/26/11 2:15:44 PM

1620 Section XIV Complications

Another way to test the dural closure involves the injection of

saline into the thecal sac via a small gauge needle, thereby

revealing any site of leakage. Any of several commercially avail-

able dural sealants may be used to augment the dural repair.

These include Tissel, fibrin glue, DuraGen, and BioGlue.

Fibrin sealant alone remains in situ for only 5 to 7 days and, as

such, is not effective in the long term. They should, therefore,

be supplemented with dural, muscle, or fat grafts.5,19 The

paraspinal muscles and fascia should be closed in at least two

layers with No. 0 or 2-0 gauge monofilament sutures in an

interrupted or figure-of-eight fashion to create a watertight

closure.

Some surgeons avoid placing postoperative drains alto-

gether because they feel like the drain may serve as a nidus for

infection and may also lead to the persistence of the communi-

cation between the intradural and extradural space. Other sur-

geons choose to place drains routinely. Drains should be

inserted subcutaneously through a distant (from the surgical

Figure 152.4. Intraoperative view of a pseudomeningocele cavity. incision) stab incision. The drain should not be placed below

the fascia as this may lead to the formation of a persistent com-

munication between the intra and extradural space. The drain

is usually removed within 48 hours but the farther away the stab

should be repaired primarily. With larger defects, however, a incision is from the primary incision, the longer the drain may

fascial graft, artificial dura, or muscle plug may be used in a be left in place. The drain should be anchored to the skin with

manner that does not cause compression of any neural ele- a purse-string suture. The skin should be closed in three layers,

ments. After the completion of the dural closure, the closure with the first set of sutures placed in the subcutaneous fat, the

may be tested by asking the anesthesiologist to elicit a Valsalva second in the deep dermis, and the third set of sutures used to

maneuver. Any sites of persistent leakage may then be sutured. bring the superficial skin surface together.

CASE 152.1

A 54-year-old man presented with progressive upper extrem- step in the management of this patient? (B) Repeat MRI

ity weakness, myelopathy, and a cervicothoracic syrinx. His showed a pseudomeningocele, which later became a CSF

preoperative images are attached. (A) He underwent a cutaneous fistula. The skin incision is shown below. (C) He

C5-C7 laminectomy with duraplasty and no fusion or instru- underwent surgical repair of his CSF cutaneous fistula with

mentation. He did well initially with improvement in his supplementation of the repair with DuraSeal. The ery-

muscle strength and his myelopathy but 2 months later, he thematous areas along the suture line that extend from the

deteriorated neurologically with his upper extremity posterior cervical area to the upper back are a result of

strength diminishing from 4/5 to 3/5. What is the next edema and pressure from a pseudomeningocele.

A B C

LWBK836_Ch152_p1617-1621.indd 1620 8/26/11 2:15:44 PM

Chapter 152 Cerebrospinal Fluid Fistula and Pseudomeningocele 1621

13. Lau KK, Stebnyckyj M, McKenzie A. Post-laminectomy pseudomeningocele: an unusual

REFERENCES cause of bone erosion. Australas Radiol 1992;36:262264.

14. Lee KS, Hardy IM II. Postlaminectomy lumbar pseudomeningocele: report of four cases.

1. Barbera J, Broseta J, Arguelles F, Barcia-Salorio JL. Traumatic lumbosacral meningocele.

Neurosurgery 1992;30:111114.

Case report. J Neurosurg 1977;46:536541.

15. Liebeskind AL, Herz DA, Rosenthal AD, Freeman LM. Radionuclide demonstration of

2. Carlson DH, Hoffman HB. Lumbosacral traumatic meningoceles. Report of a case. Neurol-

spinal dural leaks. J Nucl Med 1973;4:356358.

ogy 1971;21:174176.

16. Maycock NF, Van Essen J, Pfitzner J. Post-laminectomy cerebrospinal fluid fistula treated

3. Chumas PD, Kulkarni AV, Drake JM, Hoffman HJ, Humphreys RP, Rutka JT. Lumboperitoneal

with epidural blood patch. Spine 1994;19:22232225.

shunting: a retrospective study in the pediatric population. Neurosurgery 1993;32:376382.

17. McCallum J, Maroon J, Jannetta P. Treatment of postoperative cerebrospinal fluid fistulas

4. Dolynchuk KN, Teskey J, West M. Intrathoracic meningoceles associated with neurofibro-

by subarachnoid drainage. J Neurosurg 1975;42:434437.

matosis: case report. Neurosurgery 1990;27:485487.

18. Oppel F, Schramm J, Schirmer M, et al. Results and complicated course after surgery for

5. Epstein NE, Hollingsworth R. Anterior cervical micro-dural repair of cerebrospinal fluid

lumbar disc herniation. Adv Neurosurg 1977;4:3651.

fistula after surgery for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Technical note.

19. Pomeranz S, Constantini S, Umansky F. The use of fibrin sealant in cerebrospinal fluid

Surg Neurol 1999;52:511514.

leakage. Neurochirurgia 1991;34:166169.

6. Findler G, Sahar A, Beller A. Continuous lumbar drainage of cerebrospinal fluid in neuro-

20. Ryall RG, Peacock MK, Simpson DA. Usefulness of B2-transferrin assay in the detection of

surgical patients. Surg Neurol 1977;8:455457.

cerebrospinal fluid leaks following head injury. J Neurosurg 1992;77:737739.

7. Gass H, Goldstein AS, Ruskin R, Leopold NA. Chronic postmyelogram headache. Isotopic

21. Schumacher HW, Wassman H, Podlinski C. Pseudomeningocele of the lumbar spine. Surg

demonstration of dural leak and surgical cure. Arch Neurol 1971;25:168170.

Neurol 1988;29:7778.

8. Hadani M, Findler G, Knoler N, Tadmor R, Sahar A, Shacked I. Entrapped lumbar nerve

22. Shapiro SA, Scully T. Closed continuous drainage of cerebrospinal fluid via a lumbar suba-

root in pseudomeningocele after laminectomy: report of three cases. Neurosurgery

rachnoid catheter for treatment or prevention of cranial/spinal cerebrospinal fluid fistula.

1986;19:405407.

Neurosurgery 1992;30:241245.

9. Hosono N, Yonenobu K, Ono K. Postoperative cervical pseudomeningocele with hernia-

23. Teplick JG, Peyster RG, Teplick SK, Goodman LR, Haskin ME. CT identification of post-

tion of the spinal cord. Spine 1995;20:21472150.

laminectomy pseudomeningocele. Am J Roentgenol 1983;140:12031206.

10. Jones AA, Stambough JL, Balderston RA. Long-term results of lumbar spine surgery com-

24. Waisman M, Schweppe Y. Postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leakage after lumbar spine

plicated by unintended incidental durotomy. Spine 1989;14:443446.

operations: conservative treatment. Spine 1991;16:5253.

11. Kitchel S, Eismont F, Green B. Closed subarachnoid drainage for management of cerebro-

25. Zide BM, Epstein FJ, Wisoff J. Optimal wound closure after tethered cord corrections.

spinal fluid leakage after an operation on the spine. J Bone Joint Surg 1989;71A:984987.

J Neurosurg 1991;74:673676.

12. Krasnow AZ, Collier BD, Isitman AT, Hellman RS, Joestgen TM. The use of radionuclide

26. Zide BM, Wisoff JH, Epstein FJ. Closure of extensive and complicated laminectomy

cisternography in the diagnosis of pleural cerebrospinal fluid fistulae. J Nucl Med

wounds. J Neurosurg 1987;67:5964.

1989;30:120123.

LWBK836_Ch152_p1617-1621.indd 1621 8/26/11 2:15:48 PM

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Intradural, Extramedullary Spinal Tumors: BackgroundDokument9 SeitenIntradural, Extramedullary Spinal Tumors: Backgroundmetasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch146 p1575-1580Dokument6 SeitenLWBK836 Ch146 p1575-1580metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch147 p1581-1583Dokument3 SeitenLWBK836 Ch147 p1581-1583metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- Intramedullary Spinal Cord Tumors: Clinical PresentationDokument15 SeitenIntramedullary Spinal Cord Tumors: Clinical Presentationmetasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- Spinal Vascular Malformations: Michelle J. Clarke William E. Krauss Mark A. PichelmannDokument9 SeitenSpinal Vascular Malformations: Michelle J. Clarke William E. Krauss Mark A. Pichelmannmetasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch150 p1598-1607Dokument10 SeitenLWBK836 Ch150 p1598-1607metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch154 p1633-1648Dokument16 SeitenLWBK836 Ch154 p1633-1648metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch06 p65-73Dokument9 SeitenLWBK836 Ch06 p65-73metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch151 p1608-1616Dokument9 SeitenLWBK836 Ch151 p1608-1616metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch148 p1584-1590Dokument7 SeitenLWBK836 Ch148 p1584-1590metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch137 p1485-1486Dokument2 SeitenLWBK836 Ch137 p1485-1486metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- Primary Malignant Tumors of The Spine: Gregory S. Mcloughlin Daniel M. Sciubba Jean-Paul WolinskyDokument12 SeitenPrimary Malignant Tumors of The Spine: Gregory S. Mcloughlin Daniel M. Sciubba Jean-Paul Wolinskymetasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- Postlaminectomy Deformities in The Thoracic and Lumbar SpineDokument6 SeitenPostlaminectomy Deformities in The Thoracic and Lumbar Spinemetasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch140 p1511-1519Dokument9 SeitenLWBK836 Ch140 p1511-1519metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch138 p1487-1498Dokument12 SeitenLWBK836 Ch138 p1487-1498metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bone Grafting and Spine FusionDokument8 SeitenBone Grafting and Spine Fusionmetasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch135 p1460-1473Dokument14 SeitenLWBK836 Ch135 p1460-1473metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch144 p1553-1559Dokument7 SeitenLWBK836 Ch144 p1553-1559metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch126 p1355-1376Dokument22 SeitenLWBK836 Ch126 p1355-1376metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch131 p1411-1423Dokument13 SeitenLWBK836 Ch131 p1411-1423metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- Anterior Decompression Techniques For Thoracic and Lumbar FracturesDokument10 SeitenAnterior Decompression Techniques For Thoracic and Lumbar Fracturesmetasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch136 p1474-1484Dokument11 SeitenLWBK836 Ch136 p1474-1484metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch130 p1399-1410Dokument12 SeitenLWBK836 Ch130 p1399-1410metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch128 p1381-1389Dokument9 SeitenLWBK836 Ch128 p1381-1389metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch129 p1390-1398Dokument9 SeitenLWBK836 Ch129 p1390-1398metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch127 p1377-1380Dokument4 SeitenLWBK836 Ch127 p1377-1380metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch134 p1449-1459Dokument11 SeitenLWBK836 Ch134 p1449-1459metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch132 p1424-1438Dokument15 SeitenLWBK836 Ch132 p1424-1438metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- LWBK836 Ch125 p1345-1354Dokument10 SeitenLWBK836 Ch125 p1345-1354metasoniko81Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- SSI Plane WaveDokument214 SeitenSSI Plane WaveDiegoThomazSampaioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Among Premature Neonates: Prevalence, Mortality Rate and Risk Factors of MortalityDokument5 SeitenAcute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Among Premature Neonates: Prevalence, Mortality Rate and Risk Factors of MortalityInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Obsterics and Gynecology in NCR and BulacanDokument2 SeitenList of Obsterics and Gynecology in NCR and BulacanErville Matthew VictoriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maquet LyraDokument12 SeitenMaquet LyraMiguel YepesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence Supporting Broader AccessDokument4 SeitenEvidence Supporting Broader Accessedi_wsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hydronephrosis: September 2012Dokument19 SeitenHydronephrosis: September 2012Dwi RahmawatyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Waht-Cri-005 V2Dokument17 SeitenWaht-Cri-005 V2Innas DoankNoch keine Bewertungen

- CP Neon EncepthDokument9 SeitenCP Neon EncepthJuan Carlos HuanacheaNoch keine Bewertungen

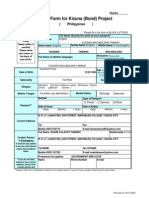

- Entry Form For Kizuna (Bond) Project: (PhilippinesDokument4 SeitenEntry Form For Kizuna (Bond) Project: (PhilippinesHusayn TamanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Placental Abruption: Causes, Risks, and TreatmentDokument30 SeitenPlacental Abruption: Causes, Risks, and TreatmentNafisat AdepojuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ceramics-Based Sealers: As New Alternative To Currently Used Endodontic SealersDokument7 SeitenCeramics-Based Sealers: As New Alternative To Currently Used Endodontic SealersfoysalNoch keine Bewertungen

- College of Nursing Kishtwar Under BGSB University, RajouriDokument3 SeitenCollege of Nursing Kishtwar Under BGSB University, RajouriBincy JiloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ejection FractionDokument3 SeitenEjection FractionKhristy AbrielleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Protocolo Triage ObstétricoDokument15 SeitenProtocolo Triage ObstétricoNEONATOLOGIA SAN FRANCISCO100% (1)

- Student Name: Karlyn Martinez: Bloomfield College Frances M. Mclaughlin Division of NursingDokument6 SeitenStudent Name: Karlyn Martinez: Bloomfield College Frances M. Mclaughlin Division of Nursingkmartinez973100% (1)

- Journey from Sevagram to Shodhgram in search of healthcareDokument24 SeitenJourney from Sevagram to Shodhgram in search of healthcareSaurabh HirekhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Affecting Utilization of Maternal Health CDokument8 SeitenFactors Affecting Utilization of Maternal Health CYussufNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding PhlebotomyDokument4 SeitenUnderstanding PhlebotomyAngelo Jude CumpioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aplio Series Radiology and Shared Service TransducersDokument16 SeitenAplio Series Radiology and Shared Service TransducersAlexander Ramirez GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICS and START Triage for Mass Casualty IncidentsDokument66 SeitenICS and START Triage for Mass Casualty IncidentsNom Nom100% (1)

- CAT Clitoral Phimosis FINALDokument14 SeitenCAT Clitoral Phimosis FINALadi130584Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pfo IntroDokument9 SeitenPfo IntroabdirashidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sonography Canada NCP 6.0 Final ENG 2020 01 07Dokument32 SeitenSonography Canada NCP 6.0 Final ENG 2020 01 07fortooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soul Guards - Corporate Profile - CompressedDokument9 SeitenSoul Guards - Corporate Profile - CompressedPrashant KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cesarean Hysterectomy With Cystotomy in Parturient Having Placenta Percreta, Gestational Thrombocytopenia, and Portal Hypertension - A Case ReportDokument4 SeitenCesarean Hysterectomy With Cystotomy in Parturient Having Placenta Percreta, Gestational Thrombocytopenia, and Portal Hypertension - A Case ReportasclepiuspdfsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admit CardDokument2 SeitenAdmit CardDeep ChoudhuryNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Pathology MCQDokument3 SeitenGeneral Pathology MCQSooPl33% (3)

- International Journal of Radiology and Imaging Technology Ijrit 5 051Dokument7 SeitenInternational Journal of Radiology and Imaging Technology Ijrit 5 051grace liwantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Sister's Keeper.. A ReflectionDokument4 SeitenMy Sister's Keeper.. A Reflectionbridj0940% (5)

- A Comparative Study of The Clinical Efficiency of Chemomechanical Caries Removal Using Carisolv® and Papacarie® - A Papain GelDokument8 SeitenA Comparative Study of The Clinical Efficiency of Chemomechanical Caries Removal Using Carisolv® and Papacarie® - A Papain GelA Aran PrastyoNoch keine Bewertungen