Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Conclusions

Hochgeladen von

sureshCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Conclusions

Hochgeladen von

sureshCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Conclusions

While there is no scientific method for weighing the balance of the drivers and constraints

detailed in this report, it is clear that an expansion of nuclear energy worldwide to 2030 faces

considerable barriers that will outweigh the drivers. The profoundly unfavourable economics

of nuclear power are the single most important constraint and these are worsening rather

than improving, especially as a result of the recent global financial and economic turmoil.

Private investors are wary of the high risk, while cash-strapped governments are unlikely to

provide sufficient subsidies to make even the first new build economic. Developing countries

will, by and large, simply be priced out of the nuclear energy market. The pricing of carbon

through taxes and/or a cap-andtrade mechanism will improve the economics of new nuclear

build compared with coal and gas, but will also favour less risky alternatives like

conservation, energy efficiency, carbon sequestration efforts and renewables. Nuclear will

simply not be nimble enough to make much of a difference in tackling climate change.

The nuclear waste issue, unresolved almost 60 years after commercial nuclear electricity was

first generated, remains in the public consciousness as a lingering concern. The nuclear sector

also continues to face public unease about safety and security, notwithstanding

recent increased support for nuclear. Governments must themselves consider the implications

of widespread, increased use of nuclear energy for global governance of nuclear safety,

security and nonproliferation, as considered in the rest of this report. It is thus likely that the

nuclear energy revival to 2030 will be confined to existing nuclear energy producers

in East and South Asia (China, Japan, South Korea and India); Europe (Finland, France,

Russia and the UK); and the Americas (Brazil and the US). One or two additional

European states, such as Italy and Poland, may adopt or return to nuclear energy. At most a

handful of developing states, those with oil wealth and command economies, may be able to

embark on a modest program of one or two reactors. The most likely candidates in this

category appear to be Algeria, Egypt, Indonesia, Jordan, Kazakhstan, the UAE and Vietnam,

although all face significant challenges in achieving their goals.In terms of technology, most

new build in the coming two decades is likely to be third-generation light water reactors,

using technology that is expected to be more efficient, safer and more proliferation-resistant,

but not revolutionary. Nuclear power will continue to prove most useful for baseload

electricity in countries with extensive, established grids. But demand for energy efficiency is

leading to a fundamental rethinking of how electricity is generated and distributed that is

not favourable to nuclear. Large nuclear plants will continue to be infeasible for most

developing states with small or fragile electricity systems. Generation IV systems will not be

ready in time, and nuclear fusion is simply out of the question. In short, despite some

powerful drivers and clear advantages, a revival of nuclear energy faces too many barriers

compared to other means of generating electricity for it to capture a growing market share by

2030. For the vast majority of aspiring states, nuclear energy will remain as elusive as ever.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Income Tax Law and Practice: Digital Assignment-2Dokument3 SeitenIncome Tax Law and Practice: Digital Assignment-2sureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 5 46 850Dokument5 Seiten3 5 46 850suresh100% (1)

- Spark Up: Making The Impossible, Possible!Dokument12 SeitenSpark Up: Making The Impossible, Possible!sureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ifs Cat 2Dokument16 SeitenIfs Cat 2sureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Retail Marketing K Mounica Slot: F1 16BCC0033: GrowthDokument4 SeitenRetail Marketing K Mounica Slot: F1 16BCC0033: GrowthsureshNoch keine Bewertungen

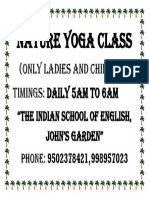

- Nature Yoga Class: (Only Ladies and Children) Timings: Daily 5am To 6amDokument1 SeiteNature Yoga Class: (Only Ladies and Children) Timings: Daily 5am To 6amsureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Branch Audit: Audit Planning Performed Jointly and Fieldwork Allocated To The AuditorsDokument3 SeitenBranch Audit: Audit Planning Performed Jointly and Fieldwork Allocated To The AuditorssureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Details Needed For IOEDokument2 SeitenDetails Needed For IOEsureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- B Quiz (Mains)Dokument41 SeitenB Quiz (Mains)sureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lab - 9 Exercise: 2: Trial BalanceDokument3 SeitenLab - 9 Exercise: 2: Trial BalancesureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dear Sponsor: Platinum - 75,000 and Above Gold - 50,000 - 75000 Silver - 25,000Dokument2 SeitenDear Sponsor: Platinum - 75,000 and Above Gold - 50,000 - 75000 Silver - 25,000sureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- DeclarationDokument5 SeitenDeclarationsureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment1 LawDokument6 SeitenAssignment1 LawsureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Statements of A Sole Proprietorship FirmDokument3 SeitenFinancial Statements of A Sole Proprietorship FirmsureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Report: The Role of Internal Audit in Effective Management in Public SectorDokument1 SeiteProject Report: The Role of Internal Audit in Effective Management in Public SectorsureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ascertainment of ProfitDokument18 SeitenAscertainment of ProfitsureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- NewsDokument151 SeitenNewssureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sterling Road, Near Nungambakkam Railway Station, Nungambakkam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu 600034: 044 2817 8200Dokument3 SeitenSterling Road, Near Nungambakkam Railway Station, Nungambakkam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu 600034: 044 2817 8200sureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- UG Students PG Students Research Scholars Academicians CorporatesDokument1 SeiteUG Students PG Students Research Scholars Academicians CorporatessureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- MAF307 - Trimester 2 2021 Assessment Task 2 - Equity Research - Group AssignmentDokument9 SeitenMAF307 - Trimester 2 2021 Assessment Task 2 - Equity Research - Group AssignmentDawoodHameedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parts of The Project Feasibility. Executive SummaryDokument3 SeitenParts of The Project Feasibility. Executive SummaryJigz GuzmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Performance and Challenges of Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Projects in BangladeshDokument14 SeitenThe Performance and Challenges of Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Projects in Bangladeshfahim asifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Firm and Asset ValuationDokument7 SeitenFirm and Asset ValuationVân TrườngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mikaella D. Del Rosario Nov. 26,2021 Bsba MM 1-3D FA1Dokument5 SeitenMikaella D. Del Rosario Nov. 26,2021 Bsba MM 1-3D FA1Mikaella Del RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Store Business PlanDokument17 SeitenMedical Store Business PlanBrave King100% (3)

- M2E - OUTLINE - Nguyen Ngoc Tu - VALUATION OF HABECODokument11 SeitenM2E - OUTLINE - Nguyen Ngoc Tu - VALUATION OF HABECOPhan Thanh TùngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Untitled 4Dokument13 SeitenUntitled 4Ersin TukenmezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive Summary - Sintang 12 MW BTG Biomass Power PlantDokument11 SeitenExecutive Summary - Sintang 12 MW BTG Biomass Power PlantKomang SuantikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cost Audit ReportDokument20 SeitenCost Audit ReportVishesh DwivediNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Experience With Private Sector Participation in Power GridsDokument43 SeitenInternational Experience With Private Sector Participation in Power GridsPedro LaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Financial Distress and BankruptcyDokument28 Seiten1 Financial Distress and BankruptcyKanika ChauhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Change of BrokerDokument1 SeiteChange of BrokerFiniscope - Investment AdvisorsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Books-Investing in Stock MarketsDokument2 SeitenBooks-Investing in Stock MarketsRitesh TiwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- SEBI As A Capital Market RegulatorDokument22 SeitenSEBI As A Capital Market RegulatorKamta Prasad SahuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital Budgeting TechniquesDokument46 SeitenCapital Budgeting TechniquesAhmad RabayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eurekahedge November 2011 Asset Flow - AbridgedDokument1 SeiteEurekahedge November 2011 Asset Flow - AbridgedEurekahedgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Equity Valuation - Case Study 2Dokument5 SeitenEquity Valuation - Case Study 2sunjai100% (6)

- KomatsuDokument11 SeitenKomatsuAmit AhujaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bllomberg Annual ReportDokument92 SeitenBllomberg Annual ReportRaghuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian Restaurant Business PlanDokument23 SeitenIndian Restaurant Business PlanAjit SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bharti Wall MartDokument1 SeiteBharti Wall MartJorge SantanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mahesh Gowande: ContactDokument2 SeitenMahesh Gowande: ContactIshan SaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solution Manual For Principles of Corporate Finance 12th Edition by BrealeyDokument3 SeitenSolution Manual For Principles of Corporate Finance 12th Edition by BrealeyNgân HàNoch keine Bewertungen

- IFM NotesDokument2 SeitenIFM NotesursubhashNoch keine Bewertungen

- 201469ar 2013 Garuda Indonesia English VersionDokument422 Seiten201469ar 2013 Garuda Indonesia English VersionAgamPatraNoch keine Bewertungen

- A L-U-V-Wy Recovery: April 6, 2020Dokument11 SeitenA L-U-V-Wy Recovery: April 6, 2020Mike HammondNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accounting Standard 34Dokument34 SeitenAccounting Standard 34Kisi Ka Dar NahiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hands On BankingDokument134 SeitenHands On BankingTaufiquer RahmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Project On SBI Channel DevelopmentDokument103 SeitenMarketing Project On SBI Channel DevelopmentRK Singh100% (1)