Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Psychotherapy Millon

Hochgeladen von

Isabel BelisaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Psychotherapy Millon

Hochgeladen von

Isabel BelisaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

JOURNAL OF PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT, 72(3), 407425

Copyright 1999, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Approaching Psychotherapy of the

Personality Disorders From the

Millon Perspective

Darwin Dorr

Department of Psychology

Wichita State University

Millons integrative model for a clinical science begins with a theory that is consistent

with current knowledge, establishes a taxonomy for classification, develops a coordi-

nated assessment system, and develops and implements interventions with the guid-

ance of the preceding elements of the model. In recent years, work on the last step of

the model, clinical interventions, has accelerated rapidly, and the model now permits

the therapist to directly extrapolate specific treatment goals, objectives, and tech-

niques to the practice of therapy with the individual patient. This article summarizes

how treatment planning and implementation flows logically from the Millon model.

As part of his efforts to find ways to encourage integration in psychology, Millon

and his colleagues (Millon, 1990; Millon & Davis, 1996) developed a model for a

mature clinical science. The model articulates explicit theories that serve as explan-

atory and heuristic conceptual schemas that are consistent with established knowl-

edge. Further, Millon established a taxonomy for purposes of classification,

designed instrumentation based on theoretical groundings and taxonomies, and

used these theoretical and psychometric tools to plan and implement psycho-

therapeutic interventions. His work over the past 30 years resulted in significant de-

velopments in the first three steps of this model. In recent years, work on the fourth

step, clinical interventions, has accelerated rapidly, and the model now permits the

therapist to directly extrapolate specific treatment goals, objectives, and techniques

to the practice of psychotherapy with the individual patient. This article summa-

rizes how treatment planning and implementation flows logically from the Millon

model. This extension of the theory promises to be one of the most exciting devel-

opments in the melding of the clinical science of assessment and intervention.

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

408 DORR

Millon (Millon & Davis, 1996) strongly emphasized that in a clinical science,

theory should relate directly to intervention. Millon (1995) was sharply critical of

the practice of applying therapeutic interventions based on what one has learned in

ones training rather than by careful assessment of the personality and

psychopathology of the patient. He observed that most therapists fail to link

thoughtful diagnosis to thorough treatment planning. To Millon, the person is at

the center of the psychotherapeutic experience, and it is there that therapeutic plan-

ning should begin. Otherwise, we would all be like small boys plying our respec-

tive therapeutic hammersbe they cognitive therapy, psychodynamic, gestalt,

behavioral, or family therapyoblivious to the therapeutic needs of the patient.

Millons theory is inclusive and anticipates the current integrative approach to

psychotherapy (Norcross & Goldfried, 1992). In the second edition of his personal-

ity disorders volume, Millon (Millon & Davis, 1996) cited the work of Werner

(1940), who maintained that development proceeded in three stages: (a) from the rel-

atively global, to (b) the relatively differentiated, to (c) an integrated totality. Millon

wrote that if the emerging field of psychotherapy had developed according to

Werners model, we might today have an integrated theory of psychotherapy. In-

stead, we have a therapeutic Tower of Babel with literally hundreds of specific types

of therapies described in the literature (Garfield, 1994). Millon (1990) described

how schools of psychotherapy sometimes evolve into imperious dogmas that close

off other points of view. Disciples submit to infallible authorities who vehemently

dispute the validity of competing theories. Indeed, as early as 1969, Millon asserted

that the disciples of such schools, often less creative than their creators, tend to un-

critically and devotedly defend the tenets of the theory as sacred dogma. In fact,

Millon speculated that dogmatism serves to protect the adherent from experiencing

underlying self-doubt and insecurity concerning validity of ones convictions.

Turning his attention from dogma to eclecticism, Millon (Millon & Davis,

1996) asserted that at least eclecticism had the virtue of humility. To Millon, eclec-

ticism is a response to practical necessity. Patients present with a multitude of

problems, and compassionate therapists reach for every available tool to respond

to clinical exigencies. Eclecticism is more empirical than theoretical. It represents

a pragmatism in which the clinician chooses whatever psychotherapeutic tech-

nique works best with the patient. Literally meaning to select from what appears to

be the best, eclecticism is the precursor of the contemporary integration movement

in psychotherapy. Eclecticism, of necessity, is atheoretical. Millon referred to it as

more of a movement than a theoretical orientation. Technical eclecticism accepts

the position that therapeutic techniques could be separated from their generative

theories and applied to clinical problems without endorsing or validating the the-

ory. To Millon, eclecticism is a more reasonable alternative to dogma. However,

he pointed out that eclecticism is more like a coping mechanism than a consciously

developed theoretical orientation. Further, he remarked that there are actually no

theory-neutral facts. Theory can be ignored, but it will not go away. Thus, Millon

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

PSYCHOTHERAPY WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS 409

argued that a clinical science must begin with conceptual theories from which tax-

onomies, assessment instruments, and, ultimately, interventions are derived. Sci-

ence can never be truly atheoretical. Hence, he argued that there is a need to move

beyond eclecticism toward a more integrative approach to therapeutic theorizing.

Millons model calls for an integrative approach in which specific therapeutic

strategies and tactics derive logically from the theoretical conceptualization of the

person at the center of the therapy.

Millons current approach to psychotherapy is a logical extension of his

biosocial-learning theory. Depending on the purposes of the writing, the approach

has been alternatively described as synergistic psychotherapy, personologic psy-

chotherapy, personality therapy, or simply the Millon perspective. The admixture

of spheres incorporated in the name biosocial-learning theory emphasizes the view

that personality and psychopathology develop as a result of the interaction be-

tween organismic and environmental forces, an interaction not well recognized at

the time that Millon (1969) introduced the idea. In his view, this interaction is

ceaseless, beginning at conception and continuing throughout the life cycle. As a

result, persons who share similar biological and constitutional predispositions may

present with differing personality characteristics and clinical syndromes as a func-

tion of their experiences. Biological and constitutional factors can shape, facilitate,

or limit the nature of the individuals learning and experiences in multiple ways.

Consider, for example, the role of perception. As a result of differing constitu-

tional characteristics, persons may perceive the same objective environment in dif-

ferent ways that, in turn, may contribute to marked individual differences in their

reaction to the environment. Through this mechanism, the same objective envi-

ronment becomes, in psychological actuality, multiple environments.

Millon does not imply a simple, unidimensional biological determinism in this

model, contending that biological maturation is dependent on a favorable environ-

mental experience. The biosocial-learning model posits a circularity of interaction

in which dispositions in early childhood evoke counterreactions from others that

subsequently enhance these dispositions. Children actively interact with their envi-

ronment, thus contributing to the conditions of their environment, which, in a recip-

rocal manner, provide a template for reinforcement of their biological tendencies. In

Millons words, Each person possesses a biologically based pattern of sensitivities

and behavioral dispositions that shapes the nature of his or her experiences and may

contribute directly to the creation of environmental difficulties (Millon & Davis,

1996, p. 67).

POLARITIES

Millon (1969) presented an initial version of his biosocial-learning theory in which

he posited three broad polarities that govern all mental life. These polaritiesac-

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

410 DORR

tivepassive, pleasurepain, and selfotherare used as a means of describing

various types of pathological personalties. For example, the narcissistic personality

is described at that time as a passive-independent character.

Millon continued to reassess, revise, and extend his conceptualization of per-

sonality and personality disorders. He was influenced by Godels (1931) incom-

pleteness theorem that no self-contained system can prove its own propositions.

As a result, he voyaged beyond the parameters of psychology to examine universal

principles that can be found in older, more established sciences such as physics,

chemistry, and biology. Using observations gleaned from this broad, scientifically

historical view, Millon concluded that the principles of evolution are essentially

universal and that the lessons to be learned from evolutionary principles have a

close correspondence to his earlier (1969) biosocial-learning theory. In his book

on personology (Millon, 1990), the polarity model was reconceptualized as conso-

nant with evolutionary theory. For example, the pleasurepain polarity reflected

the matter of actually being versus nonbeing, existence versus nonexis-

tence. Organisms exist (i.e., resist entropy) by seeking pleasure (life enhance-

ment) or by avoiding pain (life preservation). The basic polarities were plaited into

a complex matrix that faithfully described the broad styles of the various personal-

ity styles.

In the personality disorders, these polarities are imbalanced in various ways.

The configuration and direction of the imbalance globally describes the pathology

characteristic of the specific personality disorder. They provide the therapist with a

general template that can be used in developing overall long-range treatment strat-

egies that guide the entire course of the therapy. The overarching objective is to

rebalance the imbalanced polarities. To give a few examples: schizoids, avoidants,

and depressives are pleasure deficient. Thus, a long-range therapeutic strategy for

these patients may be to enhance their capacity to experience pleasure and to en-

gage in life-enhancing tendencies. The avoidant and the depressive personalities

are imbalanced in the direction of the pain polarity. Thus, a long-range strategy

would be to lessen their cathexis to pain. In the case of the self-defeating and the

sadistic personalities, there is a reversal in the pleasurepain polarities. Hence, the

long-range strategy is to transpose the painpleasure discordance. In the case of

borderline personality disorder, the motives and aims inherent in each of the polar-

ities are of average strength, but all three of the polarities are in conflict. There is

intense conflict between enhancement and preservation, accommodation and

modification, as well as individuation and nurturance. The conflicting polarity

vectors reflect an unstable pattern of intense ambivalence and inconsistency that

characterizes the borderline syndrome. Millons model describes the emotional

vacillation and the behavioral unpredictability. Thus, the overall therapeutic strat-

egy is to reduce conflict among the painpleasure, activepassive, and selfother

polarities.

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

PSYCHOTHERAPY WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS 411

Millon also identified what he called perpetuating tendencies, or characteristics

of the personality disorder that actually contribute to the perpetuation of the disor-

der itself. For example, the overall style of the histrionic is to orient his or her at-

tention to the external world. Passing details become preoccupations, preventing

experiences from being digested and embedded within the persons inner world.

This preoccupation with the external world interferes with the process of reflective

self-examination, resulting in a failure to link affect and behavior. Behaviors are

emitted before they are linked and organized by the mental processes of memory

and thought. Unless life events are metabolized and integrated, the individual

gains little from them. Hence, the histrionics maturation is unchanged by experi-

ence. The maturity learning curve remains flat. The opportunity to develop a foun-

dation of life learning experiences from which to draw in future interactions is lost.

The histrionic is bereft of an inner storehouse of memories, ideas, and thoughts

that add up to ego strength. The histrionics excessive preoccupation with the ex-

ternal, to the neglect of the self, perpetuates the shallowness or emptiness, which in

turn propels the person to further seek gratification and a sense of substance from

others.

A therapist sympathetic with the Millon approach might attempt to help the his-

trionic person turn more toward the self, to look inward, pause, and reflect on what

is happening intrapsychically. Perpetuating tendencies, by definition, contribute to

the long-standing patterns of maladaption seen in the personality disorders. For

this reason, interventions aimed at altering perpetuating tendencies are classed,

along with balancing polarities, as strategies aimed at broad, long-term objectives.

DOMAINS

Millon (1990; Millon & Davis, 1996) maintained that an integrative theory must

consider multiple spheres or domains of personality (described in detail in other ar-

ticles in this series). Based on a review of the research literature, Millon delineated

eight major domains of personality. Specifically, a Millonian therapist would re-

view the clinical data, including available assessment instruments, for indications

of deficiencies in one or more of the eight functional or structural domains. Se-

lected domains are targeted for specific tactical interventions at the individual ses-

sion level. To illustrate, borderline patients tend to be highly deficient in the

interpersonal domain. Described as interpersonally paradoxical, they need atten-

tion and affection, yet they tend to be unpredictable, contrary, manipulative, and

volatile. Thus, they may elicit rejection rather than support. Given this dynamic, in-

terpersonal therapeutic approaches such as those of Benjamin (1993) might be em-

ployed. Specifically, there would be an emphasis on the development of a strong

alliance. Next, the patient would be encouraged to examine and recognize these

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

412 DORR

maladaptive interpersonal patterns. Role play, discussion, teaching, and modeling

are techniques that might be used to help the patient understand these maladaptive

interpersonal patterns. The therapist may step into the role of coach, supporting

healthy life choices and severing maladaptive relationships.

The morphologic organization of the borderline person is split. Inner structures

are sharply segmented and conflictual. There is a marked lack of consistency or

congruity leading to limited psychic order and cohesion. Nonintegrated emotional

functioning and eitheror thinking are present. Cognitive therapy may be em-

ployed to address the pervasive splits. The patient may be asked to critically reas-

sess assumptions and cherished beliefs that underlie the persisting splitting

defense. The tendency to lump ideas and people into categories may be chal-

lenged. For example, the patient who sorts others into dichotomous classes such as

trustworthy versus untrustworthy may be helped to understand that there are de-

grees of trustworthiness within multiple social conditions. Matters of gradation

and degree would be emphasized over sharp dichotomies.

The borderline is also deficient in the self-image domain. The self-image is de-

scribed as uncertain. Identity is nebulous and wavering. There may be an inner

sense of emptiness. The individual may present with an as-if quality or with sev-

eral selves, often misperceived as dissociative identity disorder. The interven-

tions summarized earlier may contribute to a more stable sense of identity by

fostering a greater sense of emotional and behavioral control. The self-image may

be further stabilized by the therapists control of countertransference. Specifically,

the histories of borderline patients are often littered with the bones of shattered re-

lationships. Self-image naturally suffers as a result. When the therapist under-

stands the personal dynamics of the borderline patient, it is easier to control the

potential negative countertransference reactions, allowing the therapist to control

the session and to be compassionately available. In this safe holding environment

in which the borderline patients interpersonal antics cannot disrupt the relation-

ship, the patient can develop a healthier self-image, or at least a self-image that is

not damaged or loathsome.

To summarize thus far, Millons approach to treatment is both strategic (broad/

long-term) and tactical (immediate/within session) in nature. The personologic

therapist engages in broad, strategic interventions that seek to realign imbalances

in polarities and to counter perpetuating tendencies as well as session-based tacti-

cal interventions that target deficiencies in specific domains.

SELECTING TACTICAL MODALITIES

It must be emphasized that Millons personologic psychotherapy is not yet another

school of psychotherapy. Rather, it is a psychological and philosophical model

that allows the thoughtful integrationist to conceptualize the assessment and treat-

ment of individuals and utilize this conceptualization as a guide in drawing on a

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

PSYCHOTHERAPY WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS 413

wide array of therapeutic modalities from which to mount the treatment plan. The

model is inclusive rather than exclusive. However, unlike eclecticism, which can

be disorganized and haphazard, Millons personologic therapy provides a theory of

psychopathology and a method for directing deliberate interventions that are logi-

cally derived from the model. It affords the clinician a matrix for planfully building

a treatment plan based on logic and thoughtful assessment of the patients needs,

deficiencies, and tendencies. Tactical modalities may be chosen from the array of

therapeutic techniques available to all therapists. The point is that therapeutic inter-

ventions are selected based on careful conceptualization of the case. Tactical mo-

dalities are chosen according to their potential relevance to treating deficiencies

within each of the domains.

Consider, for example, the behavioral realm. The behavioral construct includes

both concrete and observable actions. One of the behavioral domains is expressive

acts. Expressive acts may be generally thought of as the operant and respondent

repertoire of the person. The expressive domain encompasses the observable as-

pects of physical and verbal behavior including what a person actually does and

says. When working with problems within this domain, it is obvious that tech-

niques drawn from behavior therapy would be employed. We may be reminded

that Millon considered his initial conceptualization to be a variant of social learn-

ing theory (biosocial-learning theory), and it is not surprising that he would be

sympathetic to the behavioral approaches to therapy in the behavioral realm. Even

in its contemporary form, the Millon conceptualization asks where the patient

seeks reinforcement (self or other) and in what manner reinforcement is sought

(active or passive). Working within the Millon point of view, Donat (1995) de-

scribed the varieties of behavioral interventions that may be employed when work-

ing within the Millon system. Respondent (classical) conditioning techniques may

be chosen to deal with emotion-based conditioning problems such as social phobia

and generalized anxiety disorders. Operant forms of behavioral therapy may be

employed, particularly when it is essential that the expressive acts of the patient

are harmful to self or others. Of special relevance are the self-management proce-

dures. The therapist may employ self-monitoring procedures, examine self-state-

ments associated with the problem behavior, or identify subjective units of distress

for interventions.

The other behavioral domain is interpersonal conduct. Interpersonal behavior

has expressive significance in social interaction. Deficiencies in the interpersonal

realm are typically remediated with interpersonal therapies. Millon favors the

work of Kiesler (1986) and Benjamin (1993). To the interpersonal therapist, the

problems of individuals reside in their current transactions with significant others.

When interpersonal interactions are fraught with misperceptions, poor communi-

cation, failing to attend, and other unsuccessful interchanges, self-defeating mal-

adaptation takes place. Interpersonal therapy focuses on the patients habitual

interactive and hierarchical roles in the social system that perpetuate the pathol-

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

414 DORR

ogy. Millon noted that interpersonal therapy broadens the scope of the therapy

from the individual to the system in which the individual is functioning.

Millon also emphasized the role that group therapy can play in treating difficul-

ties in the interpersonal domain. By its very nature, group psychotherapy provides

a forum for dealing with interpersonal issues in an emotionally charged atmo-

sphere. Maladaptive interpersonal strategies become quickly apparent and may be

handled within the context of the group. Craig (1995) presented a concise review

of the use of interpersonal therapy within the Millon approach. Craig advocated a

time-limited approach. The patient usually knows in advance how much time will

be devoted to the therapy. Interpersonal therapy is focused and stream of con-

sciousness process therapy is not done. Interpersonal therapy concentrates on the

present, not on the past, and centers on interpersonal relationships in the here and

now. Various techniques include advice giving, suggestion, setting limits, educa-

tion, and direct help.

Domains falling within the phenomenological realm consist of cognitive style,

self-image, and object relations. Cognitive therapy techniques are favored when

addressing deficiencies in cognitive style. According to Will (1995), Stoic philos-

ophy was the earliest precursor of contemporary cognitive therapy. The basic as-

sumption is that one can change ones emotions by changing ones cognitions.

Millon noted the cognitive therapy tactics of Beck and Freeman (1990). Cognitive

therapy examines the patients schemas, specific rules that govern information

processing and behavior. Schemas may be classified into a number of categories

such as personal, cultural, and family. Patients are helped to focus on automatic

thoughts and their contribution to emotions. Patients are also encouraged to assess

their cognitions and are given ways to challenge them when appropriate. Assump-

tions are examined, sequences of thoughts are reviewed, and strategies to correct

maladaptive cognitive styles are mounted. Will (1995) outlined the theoretical as-

sumptions cognitive therapy makes about human behavior and how it can be con-

ducted within the context of the Millon point of view. He described how

maladaptive functioning in the cognitive domain is approached by demonstrating

the link between thoughts and emotions.

Deficient object relations result from inaccurate, vacillating, or sterile inter-

nalized representations of others. A contemporary psychoanalytic model, object

relations theory represents the nexus of selected tenets of classical psychoanaly-

sisHartmanns (1939/1958) concept of the conflict-free portion of ego, social

concepts from Sullivanian (1953) theory, elements of developmental theory, and

existential and humanistic thought (Dorr & Woodhall, 1986). Millon cited Green-

berg and Mitchell (1983) as proponents of object relation therapy. I would add

that the works of Mahler, Pine, and Bergman (1975), Kernberg (1985), and Mas-

terson (1976) are especially helpful to the therapist working with object relations

difficulties. Van Denberg (1995) described an approach to treating deficient ob-

ject relations within the context of Millons theory. He emphasized the use of

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

PSYCHOTHERAPY WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS 415

transference interpretations, describing how the patient relives old conflicts,

placing the therapist into roles from the past. The clinician must be sensitive to

these subtle projections and resist the patients attempts to replay past conflicts

while remaining libidinally available. A major focus of the therapy is to counter

the patients tendency to reestablish and, thus, reexperience pathological object

relations. If therapist and patient are successful, the patient will come to develop

new and healthier relationships with significant others.

With regard to approaches to difficulties with self-image, Millon employed the

work of self-image therapists ranging from the early European existentialists to the

reality therapy of Glasser (1965). As understood by Millon, the aim of self-image

therapists is to free patients to develop a more realistic and favorable self-image.

Millon also cited the work of Rogers (1967) in which unconditional positive re-

gard helps the patient to develop a nonjudgmental self-view. Drawing on the work

of Kohut (1971, 1977), McCann (1995) outlined a means of treating self-image

within a Millonian perspective. Kohut viewed the self as a stable structure that lies

at the center of all psychological experiences, providing the individual with a sense

of selfhood. A Kohutian approach emphasizes empathic attunement to the pa-

tients experiences of self. The major role of the therapist working with self-image

deficiencies is to understand and to explain. The therapists compassionate empa-

thy for the patients wound helps the patient to feel understood, respected, and ac-

cepted. This permits healthy growth of the sense of self. Explanation can be in the

form of interpretation in which the meaning of certain themes or conflicts is

brought to light for the patient. A second method of explanation is enactment, in

which a patients unconscious conflicts are expressed in a particular interpersonal

context.

The intrapsychic realm consists of two domains, regulatory mechanisms and

morphologic organization. Regulatory mechanisms are strategies of self-defense,

self-protection, need gratification, and conflict resolution. They represent impor-

tant internal processes that may serve to organize all other functional domains in

some form of unobservable, self-protective strategy. Kubacki and Smith (1995)

reviewed approaches to treating defective ego defenses in a manner that is consis-

tent with Millons perspective. They employed contemporary psychoanalytic con-

cepts and methods. After attuning contemporary psychoanalytic taxonomies with

the Millon categorization, they ordered defensive strategies by psychostructural

level. (The reader may wish to consult Stone, 1980, for a discussion of psycho-

structural levels.) At the psychotic level of personality organization, defenses are

archaic, without boundaries, and primitive. Defenses are mounted primarily to

avert total disintegration and loss of self. Treatment at this level focuses almost en-

tirely on the lack of a validated self. At the prepsychotic to borderline levels, de-

fensive strategies are also primitive and include splitting, primitive denial,

primitive idealization, and omnipotence. These patients are very difficult to work

with because of the pervasiveness of the splitting and the potential for projective

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

416 DORR

identification to pull the therapist into a destructive countertransference. The pri-

mary means of dealing with these matters is to control the countertransference as

carefully as possible. In so doing, the therapist resists being caught up in the more

destructive defensive strategies, such as projective identification, while remaining

compassionately available to the patient. Confrontation and clarification may some-

times help the patient work toward some degree of internalization. Of course, one

always works to promote higher level defenses through avenues such as activity

therapy when it is available. At the neurotic level, the therapist is freer to use

higher levels of confrontation and interpretation. The neurotic is better able to tol-

erate interpretation of resistances and to access unconscious material to work it

through.

Morphologic organization (structure) is the architecture that serves as a scaf-

folding or framework of an individuals psychic interior. Millon suggested the use

of intrapsychic therapy for intervention at the morphologic level. Intrapsychic

therapy focuses on internal mediating processes and structures that presumably

underlie and give rise to overt behavior. Intrapsychic therapists seek to help recon-

struct the patients personality. Dorr (1995) described how psychoanalytic psy-

chotherapy addresses morphologic deficits in various personality disorders. This

work draws heavily on contemporary analytic thinking and techniques drawn from

object relations theory. Specific techniques such as clarification and confrontation

are suggested. However, Dorr placed special emphasis on relatedness and the role

of transference and countertransference in the therapy. Because of the fragile

structure of personalities of patients with personality disorder, they do not have a

healthy internalized sense of self or rich, enduring internalized representations of

significant others. As a result, their interpersonal relations are usually tumultuous,

destructive caricatures of mature relatedness. This view holds that healthy struc-

ture is built through healthy relatedness. A major factor that perpetuates the defi-

cient or fragile structure is continued pathological interactions with significant

others. Further, in treatment, pathological transference reactions may develop with

the patients own therapist, which may foment destructive countertransference re-

actions in the therapist, thus perpetuating the structural pathology in the patient. If,

on the other hand, the therapist carefully controls the countertransference reaction

while maintaining a compassionate holding environment, the patient no longer has

the opportunity to play out unhealthy relatedness. Because of the emotional avail-

ability of the therapist, healthy relatedness is experienced, perhaps for the first

time, and morphological structure strengthens.

Finally we come to the biophysical realm with its single domain, moodtem-

perament. Characterological mood suffuses virtually every aspect of an individ-

uals existence. It colors all experiences and relationships. Two domain-specific

interventions are discussed. First is the practice of using medication. A Millonian

therapist would not likely be opposed to referring a patient for a medical consulta-

tion if it is believed that medication might be useful to the patient. However, medi-

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

PSYCHOTHERAPY WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS 417

cations are usually not terribly helpful in treating the personality disorders

themselves, but are primarily useful with Axis I disorders. If a medication were

used, a Millonian therapist would be especially interested in the patients psycho-

logical response to the changes brought about by the medication. Of cardinal inter-

est would be the meaning the patient makes of the changes brought about by the

medication. Although a given medication may produce the same biological effect

in all patients, the psychological impact of the medication is more important to the

psychotherapy. For example, one depressed patient may respond well to an antide-

pressant and utilize the renewed psychic energy to tackle and overcome the endur-

ing problems that led to the depression in the first place. Another might respond

physiologically to the medication in a similar way, yet believe that the therapeutic

effect is artificial and feel guilty that the therapeutic effect was not based on psy-

chological work. To Millon, the determinant of the effectiveness of a medication is

not its chemical effect, but rather, the psychological significance of the effect.

Another approach to intervention in the moodtemperament domain was articu-

lated by Hyer, Brandsma, and Shealy (1995), who described the use of experiential

therapies in treating pervasive moodtemperament difficulties. They described ex-

periential therapies as a broad array of techniques ranging from Gestalt to client cen-

tered to types of psychoanalytic approaches and so on. Affect is considered to be

primary, and experiential therapy helps the patient to focus attention on the target

feeling, to symbolize the experience, and to consolidate new meanings that grow out

of the experience. Affect contributes to the unfolding of the process. In the authors

view, the change process consists of many small steps in which events are

reexperienced emotionally in the here and now, resulting in meaning shifts. Experi-

ential therapy seeks to help the patient go through a corrective emotional experience

that allows the psychological structure to change in a healthy direction.

POTENTIATED PAIRINGS AND

CATALYTIC SEQUENCES

Millons therapeutic system also employs potentiated pairings and catalytic se-

quences to mount a therapeutic program. Potentiated pairings occur when the ther-

apist combines two or more therapeutic procedures simultaneously to overcome

problematic characteristics or resistances that might compromise a single ap-

proach. Potentiated pairings are selected in a manner that is logically consistent

with the theoretical conceptualization of the patients problems.

Catalytic sequences utilize multiple treatment modalities in succession. These

are procedures in which serial treatments are applied in an order designed to have

the most impact. There are no discrete boundaries between potentiated pairings

and catalytic sequences. The expectation is that interventions in tandem or se-

quence will contribute to therapeutic synergy, thus increasing the effect size. The

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

418 DORR

action of combining interventions is especially important with the personality dis-

orders because of their notorious resistance to treatment. To illustrate the use of

potentiated pairings and catalytic sequences, let us return to the example of the his-

trionic patient in whom we have polarity imbalance and perpetuating tendencies

that interfere with growth. A first step might be to help the patient control

hyperemotionality because it leads to a sense of being overwrought or out of con-

trol. The therapist may teach the relaxation response, encourage the patient to

stay in the present, instruct the patient in self-soothing exercises, or engage in

any other intervention that will help the person feel in control of strong emotion.

This intervention may be accompanied or followed by cognitive cause-and-effect

reasoning, interchanges that may further encourage the calm, thoughtful process-

ing of information. The development of clear thinking skills may set the stage for

longer term exploratory therapy. If depression is present, a referral to a physician

for a medication consultation may be made. As the initial crisis settles, the thera-

peutic relationship becomes especially important in keeping the patient in treat-

ment to get on with the work and in using the therapeutic process to help the patient

develop a deeper, healthy relationship with the therapist. This, in turn, may pro-

vide a foundation for healthier, more sustained relationships with significant oth-

ers. Family or couples therapy may help to repair and strengthen relationships.

Group therapy with persons having similar problems may provide opportunities to

see histrionic behavior in others that patients may not readily see in themselves.

Finally, their own growing maturity may be recognized by the group, which may

be an especially powerful reinforcer for the patients.

COMMON FACTORS, TECHNIQUES, AND

THERAPIST VARIABLES

Millons conceptualization is mindful of the common factors in psychotherapy

(Garfield, 1995). Millon viewed the common factors approach as a useful gauge by

which to estimate the incremental efficacy achieved by theoretically integrative ef-

forts. Because they represent distillations of the active ingredients of therapy, the

common factors may represent the lowest common denominator of therapy. To

Millon, they, at best, constitute the minimum of what good therapy should be. The

common factors approach does not represent the maximum of what good therapy

might achieve.

Millon is cognizant that technique accounts for only about 15% of the outcome

variance in psychotherapy research. On the other hand, he is less than enthusiastic

about the common factors because, like eclecticism, the common factors approach

is insufficiently theoretical. Millon described the common factors as a necessary

but not sufficient basis for a scientific psychotherapy. He pointed out that even if

the common factors were more clearly delineated, it would be difficult to articulate

the underlying mechanisms mediating their efficacy.

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

PSYCHOTHERAPY WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS 419

As to technique, as Millon conceptualized his approach to therapy, it is unlikely

that any legitimate therapeutic technique would be summarily excluded from a

personologic therapy plan. However, the clinician would be closely questioned as

to why a particular intervention was chosen for a particular client, why the inter-

vention was selected at a particular time in the therapy, and what the strategic or

tactical goals and objectives might be for the intervention. Millons conceptualiza-

tion does not present a tight description of a rigid orthodox approach to each per-

sonality disorder. Rather, there is an attempt to address the therapeutic issues

raised in a manner that is logically consistent with the conceptualizations of the

personality disorders as articulated within the model of personologic therapy.

Millon has little to say about the personality of the psychotherapist. However,

considering the research (Lambert & Bergin, 1994) that identifies considerable in-

dividual differences in effectiveness across therapistseven when training was

manualizedsome discussion of therapist variables may be useful. It is reason-

able to conclude that the personologic psychotherapist must possess a broad view

of personality, and for that matter, psychology itself. There is little room for

dogma in Millons system. Because people are so complex, theoretical conceptu-

alizations (and therapists) must respect this complexity. Interventions must flow

logically from broad and rich formulations of the person. Rigid adherence to a par-

ticular conceptualization of psychopathology or to a particular technique would

not allow the therapist to access the entire scope of the change process that might

be utilized with a specific patient. In short, a personologic therapist would likely be

high on the characteristic of openness and low on authoritarianism.

TREATMENT PLANNING: AN EXAMPLE

The Millon system insists that the choice of therapeutic interventions flows directly

out of the overall theoretical conceptualization of the patient. Consider the case of

the antisocial personality. The therapeutic strategies and tactics employed by the

Millon system are summarized in Table 1. The matter of goals is clear. In designing

a treatment plan for the antisocial, as for all patients, the clinician should maintain a

balance between the overall conceptualization of the person (strategies) and more

specific session-based aims (tactics). Viewing the antisocial person as one in whom

there is a serious imbalance among the great polarities of life, the personologic ther-

apist would seek to establish some reasonable equivalence between the unbalanced

polarities.

Personologic theory conceptualizes the antisocial as weak on the preservation,

accommodation, and nurturance polarities; average on the enhancement polarity;

and strong on the individuating and modifying polarities. Accordingly, the thera-

pist would use a strategy that attempts to reduce the patients almost exclusive em-

phasis on the self by encouraging him or her to develop a stronger awareness of

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

420 DORR

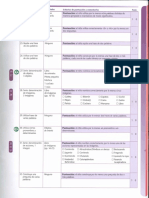

TABLE 1

Therapeutic Strategies and Tactics for the Prototypical Antisocial Patient

Strategic goals

Balance polarities

Shift focus more to needs of others

Reduce impulsive acting out

Counter perpetuating tendencies

Reduce tendency to be provocative

View cooperation and affection positively

Reduce expectancy of degradation

Tactical modalities

Offset heedless, shortsighted behavior

Motivate interpersonally responsible conduct

Alter deviant cognitions

others who are separate human beings, who have value, and who are in possession

of rights. In time, the patient may gain an increased sensitivity to the needs and

feelings of others as well. The overly active style of extracting rewards by exploit-

ing others would be confronted. The value of flexible accommodation of others

would be taught. The therapist may appeal, if necessary, to the patients prideful

self-interest by pointing out that his or her needs could be fulfilled faster and easier

if these new attitudes were adopted.

The antisocial is weak on the life-preserving polarity of the survival aims. This

weakness may have resulted in physical injury as well as financial and social

losses. With this characteristic in mind, the therapist would teach the patient the

survival value of moderating this behavior to avoid unnecessary loss.

Another strategic goal that emerges from the conceptualization of the patient

would be to counter perpetuating tendencies. In the antisocial, the potential for

perpetuating tendencies to cause difficulty is enormous. The pathological ele-

ments of the antisocial disorder itself perpetuate its continuance. The antisocial

person perceives others as dangerous and untrustworthy and treats them as such.

This behavior provokes like-mindedness in others and evokes their aggressive be-

havior. The result is that the patients perception of others as dangerous is continu-

ally reinforced, perpetuating the maladaptive behavior.

A related perpetuating tendency is often the antisocials protective attitude of

anger and resentment. It should be pointed out that this very attitude is the agent

provoking the response from others that the patient is so quick to defend against.

Equally, it should be pointed out, like the flip side of a coin, that nondefensive,

prosocial behavior will likely elicit from others a nondefensive prosocial behavior.

At the more immediate tactical level, specific deficiencies in selected domains of

personality functioning would be targeted for work during the session. In the antiso-

cials profile, the primary domain dysfunctions are expressive acts, interpersonal

conduct, and regulatory mechanisms. For example, in the expressive acts domain,

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

PSYCHOTHERAPY WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS 421

the antisocial is described as impetuous, irresponsible, and acting hastily and spon-

taneously in a restless, spur-of-the-moment manner. He or she can be counted on to

be short-sighted, incautious, and imprudent. The antisocial person often fails to plan

ahead, consider alternatives, or heed consequences. It would not be unacceptable to

the personologic therapist to utilize external forces to help control the antisocials

impetuosity, irresponsibility, and restlessness. Legal or domestic restraints may ex-

ert external controls that would help consequate and confine these expressive ten-

dencies. Various limit-setting tactics might be employed as well as cognitive

approaches that would help the patient reframe the short-sighted, imprudent tenden-

cies that cause such difficulty. It might benefit the antisocial patient to appraise the

thought processes underlying behavior and the manner in which these lead to nega-

tive consequences.

The interpersonal domain is another area of deficiency. Interpersonally, the an-

tisocial is untrustworthy; unreliable; and unable to meet personal obligations of a

marital, parental, occupational, or financial nature. Antisocial persons actively in-

trude on and violate the rights of others. They transgress established social codes

through deceitful or illicit behavior. Personologic therapy enlists the help of inter-

personal therapy to remediate deficiencies in the interpersonal realm. Benjamin

(1993) assumed that antisocials have not had a social learning history character-

ized by warm, nurturing caregivers that might have led to reciprocal warmth and

attachment. The interpersonal therapist counters these tendencies with modulated

warmth in an attempt to overcome socialization deficits. Great care, however,

should be taken not to allow the patient to believe that warmth equates with weak-

ness, as the antisocial will be quick to attempt to exploit the perceived weakness,

thus sabotaging the therapy.

The regulatory mechanisms domain is also deficient in the antisocial. The pri-

mary regulatory mechanism of the antisocial is acting out. The antisocial is rarely

constrained. Socially odious impulses are not refashioned in sublimated forms. In-

stead, they are discharged directly and hastily, usually without guilt or remorse. In

psychodynamic terms, the regulatory mechanisms of the antisocial are like primi-

tive defenses such as acting out, projection, splitting, and primitive denial. The

personologic therapist might employ cognitive interventions as described by Beck

and Freeman (1990) in addressing these deficiencies. The therapist may attempt to

help the patient understand that getting even is not synonymous with getting

ahead. The therapist may confront the antisocial person with the futility of the

talon principle. That is, the patient may be asked if he or she wants to get even or

get better. The antisocial person may be taught that long-term gain may be ac-

quired by binding frustration and using it as a source of energy to attain success. A

tactical goal would be to help the patient understand that acting out may provide

short-lived advantage (e.g., To get the offending guy off your back!), yet this

style has caused untold travail in the long run. I add that the goals could be de-

scribed as fostering prosocial thinking and behavior, reducing criminal thinking

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

422 DORR

while increasing prosocial thinking, enhancing empathy, generating control over

drives and affect, and promoting postponement of gratification.

CONCLUSIONS

This article briefly summarized some of the ways in which Millons model based

on theory, taxonomy, and instrumentation directly impacts the process of planning

and implementing psychotherapy with the personality disorders. Therapeutic inter-

ventions flow logically and easily from the assessment process that is guided by the

theory. The clinician may choose from the broad array of approaches available to

any therapist, but the selection process is guided by the overall conceptualization

and assessment of the personality and psychopathology of the patient.

In a clinical science, the primary purpose of taxonomy or assessment is to help

clarify the nature of the patients difficulties so that the therapist can be more effi-

cient and effective in formulating and implementing interventions. Most good cli-

nicians probably perform this task more or less naturally. However, Millon would

argue that the process of clinically integrating assessment information and treat-

ment planning still tends to be haphazard. At the least, the process is not formal-

ized and orderly; thus, it is not as amenable to empirical examination as it might be.

Millon called for a more formal and purposive examination of the manner in which

the clinician integrates assessment data with treatment planning.

Millon proposed a broad design for more efficiently linking treatment planning

to assessment results. His model is extremely ambitious. We may ask if our clini-

cal science is ready to move on to a more accurate articulation of exactly how our

assessment findings logically guide treatment planning and implementation.

Millon offered an approach that is at once straightforward and complex. It is ame-

nable to empirical assessment. At issue is not whether the model fits standard sta-

tistical models perfectly. Rather, the question is whether this model instructs and

guides the clinician in the process of assessment and treatment. The endpoint of a

clinical science is successful treatment. If it is found through research and practice

that Millons taxonomy guides the choice of appropriate treatment modalities, the

effort will have been a success. The hope is that his conceptualizations will stimu-

late clinical research toward exactly these questions.

The work of Millon and his coworkers is so extensive and thorough that is

tempting to view it as complete. This would violate Millons purpose. His intent is

to stimulate new theoretical and empirical approaches to the problems and issues

facing our clinical science. Although a large number of projects might be pursued

in the future, only four are summarized herein.

First, although Millon-inspired instruments are widely accepted, Millon (Millon

& Davis, 1996) himself called for further work on instrumentation. For example, he

pointed out that no dimensional assessment that examines merely scale elevation is

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

PSYCHOTHERAPY WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS 423

adequate to answer questions about the shaky stability, inflexible adaptations, and

vicious circles of personality pathology. Instrumentation in the future may be in-

creasingly sensitive to the contexts in which individuals function. We may work to-

ward developing entire systems of instrumentation.

A second form of future investigation may focus on advancing the philosophy

of science. A small number of investigators have called for a new subdiscipline of

theoretical psychology (Slife & Williams, 1997). They argue that theoretical activ-

ity in psychology is fragmented, that we cannot separate method from theory, and

that science is a theory among theories about how one evaluates theories. A formal

theoretical psychology could inform and guide researchers as to the types of explo-

ration and methods that are being employed and to determine whether these ap-

proaches are appropriate to the assumptions being made.

A third area of future investigation is the interaction among the individuals

personal systems and the social and contextual systems in which that person at-

tempts to function. Homeostasis does its work within persons and within the per-

sons social systems. When, during treatment with personologic therapy, a patient

begins to improve, the larger system in which the person is attempting to function

is likely to react, usually negatively, with attempts to reestablish homeostasis.

Thus, there is much more work to be done in assessing the ecological context in

which individual change is to take place.

I add a final note of special interest to me. Freud (1905/1993) said diseases are

not cured by the drug but by the personality of the physician (p. 259). As noted

earlier, the Millon system has little to say about the personality of the therapist. Yet

in my years of clinical experience in working with severe personality disorders, the

personality of the therapist is of utmost importance in effecting a positive response

to treatment. It would seem that a treatment system that places so much emphasis

on careful assessment of the recipient of treatment would also thoroughly examine

the personal attributes of the person performing the treatment. I hope that future re-

search will examine the role of the psychotherapists own personal characteristics

as these relate to common factors, the establishment of the therapeutic alliance,

and the role of instilling hope and expectancy in the patient.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to thank Stephanie Tilden Dorr for her editorial assistance in preparing

this article.

REFERENCES

Beck, A. T. & Freeman, A. (1990). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders. New York: Guilford.

Benjamin, L. S. (1993). Interpersonal treatment of personality disorders. New York: Guilford.

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

424 DORR

Craig, R. J. (1995). Interpersonal psychotherapy and MCMIIII based assessment. In P. D. Retzlaff

(Ed.), Tactical psychotherapy of the personality disorders: An MCMIIII based approach (pp.

6689). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Donat, D. (1995). Use of the MCMIIII in behavior therapy. In P. D. Retzlaff (Ed.), Tactical psychother-

apy of the personality disorders: An MCMIIII based approach (pp. 4065). Boston: Allyn &

Bacon.

Dorr, D. (1995). Psychoanalytic psychotherapy of the personality disorders: Toward morphologic

change. In P. D. Retzlaff (Ed.), Tactical psychotherapy of the personality disorders: An MCMIIII

based approach (pp. 186209). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Dorr, D., & Woodhall, P. K. (1986). Ego dysfunction in psychopathic psychiatric inpatients. In W. H.

Reid, D. Dorr, J. I. Walker, & J. W. Bonner (Eds.), Unmasking the psychopath (pp. 98131). New

York: Norton.

Freud, S. (1993). On psychotherapy. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete

psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 257268). London: Hogarth. (Original work

published 1905)

Garfield, S. L. (1994). Eclecticism and integration in psychotherapy: Developments and issues. Clinical

Psychology: Science and Practice, 1(2), 123137.

Garfield, S. L. (1995). Psychotherapy: An eclectic-integrative approach (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Glasser, W. (1965). Reality therapy. New York: Harper.

Godel, K. (1931). On formally undecidable propositions of principa mathematica and related systems.

Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Vienna, Austria.

Greenberg, J. R., & Mitchell, S. A. (1983). Object relations in psychoanalytic theory. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Hartmann, H. (1958). Ego psychology and the problem of adaptation (D. Rapaport, Trans.). New York:

International Universities Press. (Original work published 1939)

Hyer, L., Brandsma, J., & Shealy, L. (1995). Experiential mood therapy with the MCMIIII. In P. D.

Retzlaff (Ed.), Tactical psychotherapy with the personality disorders: An MCMIIII based ap-

proach (pp. 210234). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Kernberg, O. (1985). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. Northvale, NJ: Aronson.

Kiesler, D. J. (1986). The 1982 interpersonal circle: An analysis of DSMIII personality disorders. In T.

Millon & G. L. Klerman (Eds.), Contemporary directions in psychopathology (pp. 571597). New

York: Guilford.

Kohut, H. (1971). The analysis of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

Kohut, H. (1977). The restoration of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

Kubacki, S. R., & Smith, P. R. (1995). An intersubjective approach to assessing and treating ego de-

fenses using the MCMIIII. In P. D. Retzlaff (Ed.), Tactical psychotherapy of the personality disor-

ders: An MCMIIII based approach (pp. 158185). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Lambert, M. J., & Bergin, A. E. (1994). The effectiveness of psychotherapy. In A. E. Bergin & S. L. Gar-

field (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (pp. 143189). Boston: Wiley.

Mahler, M., Pine, F., & Bergman, A. (1975). The psychological birth of the human infant: Symbiosis and

individuation. New York: Basic Books.

Masterson, J. F. (1976). Psychotherapy of the borderline adult. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

McCann, J. T. (1995). The MCMIIII and treatment of self. In P. D. Retzlaff (Ed.), Tactical psychother-

apy of the personality disorders: An MCMIIII based approach (pp. 137157). Boston: Allyn &

Bacon

Millon, T. (1969). Modern psychopathology: A biosocial approach to maladaptive learning and func-

tioning. Philadelphia: Saunders.

Millon, T. (1990). Toward a new personology: An evolutionary model. New York: Wiley.

Millon, T. (1995). Foreword. In P. D. Retzlaff (Ed.), Tactical psychotherapy of the personality disor-

ders: An MCMIIII based approach (pp. ixxi). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

PSYCHOTHERAPY WITH PERSONALITY DISORDERS 425

Millon, T., & Davis, R. (1996). Disorders of personality: DSMIV and beyond (2nd ed.). New York:

Wiley-Interscience.

Norcross, J. C., & Goldfried, M. R. (Eds.). (1992). Handbook of psychotherapy integration. New York:

Basic Books.

Rogers, C. R. (1967). The therapeutic relationship and its impact. Madison: University of Wisconsin

Press.

Slife, B. D., & Williams, R. N. (1997). Toward a theoretical psychology: Should a subdiscipline be for-

mally recognized? American Psychologist, 52, 117129.

Stone, M. H. (1980). The borderline syndromes: Constitution, personality, and adaptation. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. New York: Norton.

Van Denberg, E. J. (1995). Object relations theory and the MCMIIII. In P. D. Retzlaff (Ed.), Tactical

psychotherapy of the personality disorders: An MCMIIII based approach (pp. 111136). Boston:

Allyn & Bacon.

Werner, H. (1940). Comparative psychology of mutual development. New York: Follett.

Will, T. E. (1995). Cognitive therapy and the MCMIIII. In P. D. Retzlaff (Ed.), Tactical psychotherapy

of the personality disorders: An MCMIIII based approach (pp. 90110). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Darwin Dorr

Department of Psychology

Wichita State University

Wichita, KS 672600034

Received January 18, 1999

Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- DC 0-5Dokument224 SeitenDC 0-5Isabel Belisa97% (35)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Ados ManualDokument27 SeitenAdos ManualIsabel Belisa75% (4)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Free English Activity PagesDokument6 SeitenFree English Activity PagesIsabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Holistic Medicine PDFDokument117 SeitenHolistic Medicine PDFGaurav Bhaskar100% (1)

- Instructor's Manual For RATIONAL EMOTIVE BEHAVIOR THERAPY FOR ADDICTIONSDokument64 SeitenInstructor's Manual For RATIONAL EMOTIVE BEHAVIOR THERAPY FOR ADDICTIONSdustypuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bayley 1Dokument10 SeitenBayley 1Isabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ayurvedic Psychotherapy - Uncrypted PDFDokument152 SeitenAyurvedic Psychotherapy - Uncrypted PDFDada DragicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bayley 2Dokument8 SeitenBayley 2Isabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delta Theory and Psychosocial Systems The Practice of Influence and Change (Roland G. Tharp)Dokument207 SeitenDelta Theory and Psychosocial Systems The Practice of Influence and Change (Roland G. Tharp)raghushiv20Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Meta-Analysis of MotivationaDokument15 SeitenA Meta-Analysis of MotivationaIsabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tratamientos Empíricamente Validados en Infancia-AdolescDokument9 SeitenTratamientos Empíricamente Validados en Infancia-AdolescIsabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetes Problem Solving by Youths With Type 1 Diabetes and Their Caregivers: Measurement, Validation, and Longitudinal Associations With Glycemic ControlDokument10 SeitenDiabetes Problem Solving by Youths With Type 1 Diabetes and Their Caregivers: Measurement, Validation, and Longitudinal Associations With Glycemic ControlIsabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Discriminative Capacity of CBCLDSM5 ScalesDokument8 SeitenThe Discriminative Capacity of CBCLDSM5 ScalesIsabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tamaño Del Efecto (D) : Bajo 0.20 Moderado 0.50 Alto 0.80Dokument2 SeitenTamaño Del Efecto (D) : Bajo 0.20 Moderado 0.50 Alto 0.80Isabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technical Report Who Guidelines For The Health Sector Response To Child Maltreatment 2Dokument94 SeitenTechnical Report Who Guidelines For The Health Sector Response To Child Maltreatment 2Isabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hossain Et Al 2020Dokument27 SeitenHossain Et Al 2020Isabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supporting Families With Children With Special Educational Needs and Disabilities During COVID19 SUBMITTED PDFDokument7 SeitenSupporting Families With Children With Special Educational Needs and Disabilities During COVID19 SUBMITTED PDFIsabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brainsci 10 00207 v2Dokument4 SeitenBrainsci 10 00207 v2Isabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vulnerable GroupsDokument7 SeitenVulnerable GroupsIsabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Getting To ChangeDokument7 SeitenGetting To ChangeIsabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- KiddyKINDL Children 4-6y English PDFDokument3 SeitenKiddyKINDL Children 4-6y English PDFIsabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hartbert Et Al., 2012Dokument6 SeitenHartbert Et Al., 2012Isabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Duck Coloring PageDokument1 SeiteDuck Coloring PageIsabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motivational Interviewing Resource List: BooksDokument4 SeitenMotivational Interviewing Resource List: BooksIsabel BelisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- So Lut Kit Cue CardsDokument3 SeitenSo Lut Kit Cue CardsIsabel Belisa0% (1)

- Unified Lesson Plan-4 DaysDokument2 SeitenUnified Lesson Plan-4 DaysErnesto De La ValleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Distancing: Avoidant Personality Disorder, Revised and ExpandedDokument294 SeitenDistancing: Avoidant Personality Disorder, Revised and ExpandedTamuna Bibiluri tbibiluriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The RequirementsDokument6 SeitenThesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirementsbk4h4gbd100% (1)

- Abuse and NeglectDokument26 SeitenAbuse and NeglectshabnamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review On Dental AnxietyDokument7 SeitenLiterature Review On Dental Anxietyea9k5d7j100% (1)

- 1 Clinical InterviewDokument14 Seiten1 Clinical InterviewClara Del Castillo ParísNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidance Within Education What Are in Store For You?Dokument3 SeitenGuidance Within Education What Are in Store For You?Jerald CaparasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bachelor of Science in CriminologyDokument78 SeitenBachelor of Science in CriminologyJenilyn Castro GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual - 2nd Edition (PDM-2) : June 2015Dokument5 SeitenThe Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual - 2nd Edition (PDM-2) : June 2015Stroe EmmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Domains of Activities:: Roles and Functions of Psychiatric NursesDokument3 SeitenDomains of Activities:: Roles and Functions of Psychiatric NursesAfif Al BaalbakiNoch keine Bewertungen

- PsyXII PDFDokument103 SeitenPsyXII PDFNida Khan100% (1)

- Poster Curriculum DevelopmentDokument1 SeitePoster Curriculum DevelopmentNur Fathin Afiqah MusaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broman-Fulks 2004 PDFDokument12 SeitenBroman-Fulks 2004 PDFJohanna TakácsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classroom ManagementDokument8 SeitenClassroom ManagementJenny Jimenez BedlanNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Contributions: Christine N. WinstonDokument14 SeitenInternational Contributions: Christine N. WinstonRicardo Arturo JaramilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- DRT2012-460419Dokument11 SeitenDRT2012-460419Sapto SutardiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1092319932Dokument109 Seiten1092319932Tessie FranciscoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PYC2015 - Social Cognitive Learning Approach - Summary No. 1Dokument8 SeitenPYC2015 - Social Cognitive Learning Approach - Summary No. 1Sbongiseni NgubaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter Thirteen Transactional Analysis of Eric Berne BY Nwokolo Chinyelu PHD & Rev SR Amaka Obineli Transactional Analysis of Eric Berne Historical BackgroundDokument8 SeitenChapter Thirteen Transactional Analysis of Eric Berne BY Nwokolo Chinyelu PHD & Rev SR Amaka Obineli Transactional Analysis of Eric Berne Historical BackgroundDabarati Iisc AspirantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angelica G Pagulayan Movie ReflectionDokument2 SeitenAngelica G Pagulayan Movie Reflectioncee jay pagulayanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acac Fall 2022 Newsletter 1Dokument8 SeitenAcac Fall 2022 Newsletter 1api-339011511Noch keine Bewertungen

- 219 SlidesDokument107 Seiten219 SlidesInfo KuidfcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oedipus The Deep Rooted Reality To HomosexualityDokument136 SeitenOedipus The Deep Rooted Reality To HomosexualitySonali DeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bab 1 B Paradigma KepribadianDokument18 SeitenBab 1 B Paradigma KepribadianalilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Removal of Homosexuality From The Psychiatric Manual by Joseph NicolosiDokument8 SeitenThe Removal of Homosexuality From The Psychiatric Manual by Joseph NicolosiwritetojoaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Santesteban-Echarrietal. 2018 BriefCopingCat AcceptedversionDokument17 SeitenSantesteban-Echarrietal. 2018 BriefCopingCat AcceptedversionAnananteNoch keine Bewertungen