Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Du Moot @

Hochgeladen von

ashish0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

9 Ansichten12 Seitenvery useful

Originaltitel

du moot @

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenvery useful

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

9 Ansichten12 SeitenDu Moot @

Hochgeladen von

ashishvery useful

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 12

1.

Reasonable Expectation of Privacy

The threshold question in determining whether a governmental

search was unreasonable is whether it infringed on an individuals

reasonable expectation of privacy. A reasonable expectation of privacy

requires: (1) the individual must have exhibited an actual, subjective

expectation of privacy and (2) the expectation must be one that society is

prepared to recognize as reasonable. In applying this analysis, it is

important to determine the nature of the specific activity at issue. In this

case, the nature of the activity specified is the governments acquisition

of Verizons records of Appellants historical CSLI.

a. Subjective Expectation of Privacy

A constitutional violation cannot occur unless the individual had a

subjective expectation of privacy. In determining whether the

individual had a subjective expectation of privacy, the Court will inquire

whether the individual [sought] to preserve [the information] as private.

Since Appellant did nothing to preserve the privacy of his CSLI, and in

fact knew that the information was not private, he did not exhibit a

subjective expectation of privacy. As such, his claim under Article 21

must fail because the government did not intrude on his reasonable

expectation of privacy.

When phone users realize they are conveying information to

others, they cannot have a legally recognized subjective expectation of

privacy. Holding that phone users have no subjective expectation of

privacy in the phone numbers they dial, since the phone users realize

they are conveying information to the phone company to use in

connecting their calls. Therefore, Appellant cannot have a reasonable

expectation of privacy in his CSLI, because he knew that he was

conveying the CSLI to his phone company to connect his calls. Every

user is aware of situations in which they have no bars are out of

service range, or might incur roaming charges. Thus, users know

they convey information about their movements to their cell service

provider. Moreover, cell phone users know that the phone company

creates records of this information for billing purposes. The knowledge

that the phone company obtains and records this information flies in the

face of a subjective expectation of privacy.

b. Objective Expectation of Privacy

Even if Appellant did harbor a subjective expectation of privacy in

Verizons records, his claim under Article 21 must still fail, because that

belief is not one that is objectively reasonable. The second prong is that

the individuals expectation of privacy must be one that society is

prepared to recognize as reasonable.

The sum of District Court precedent confirms that an expectation

of privacy in CLSI is not objectively reasonable. The Supreme Court

found that individuals have no privacy expectation in banks records of

their financial information. Taken together, this means that individuals

do not have a privacy expectation (1) in a business records, (2) in their

public location, and (3) in numbers dialed from their phone. This

precedent dictates that an individual cannot have an objectively

reasonable expectation of privacy in their cell service providers records

of their CSLI, since CSLI is a business records of the individuals

location, created by dialing on a phone. If the individual does not have

an objectively reasonable expectation of privacy in any of the three

standing alone, the individual cannot have a privacy expectation in the

three when combined.

1. Third Party Doctrine

Moreover, even if this Court were to find that Appellant did have a

reasonable expectation of privacy in his historical CSLI, Appellants

claim must still fail, as he forfeited this protection by conveying his

CSLI to a third party. The Supreme Court has consistently held that a

person has no legitimate expectation of privacy in information he

voluntarily turns over to third parties. This is true even where the

information is revealed on the assumption that it will be used only for a

limited purpose and the confidence placed in the third party will not be

betrayed.

The Supreme Court has visited this third party doctrine in

several cases, finding that no violation occurred where the information

subject to the governments search was previously conveyed to a third

party. Finding that a person had no expectation of privacy in checks,

financial statements, and deposit slips, because these materials contained

only information that was voluntarily conveyed to the bank and exposed

to its employees; a person had no privacy expectation in the phone

numbers he dialed, since he had voluntarily conveyed and exposed

this numerical information to the phone company.

The application of the third party doctrine hinges on whether the

third party created the record of the information to memorialize its own

business transaction with the individual or whether it was simply

recording a transaction between two independent parties.

CSLI is properly viewed as a business record, and the third party

doctrine therefore applies, thus negating Appellants claim under Article

21. Holding that cell site information is clearly a business record

since the phone company records this information for its own business

purposes, including optimizing service and billing, and the government

does not require it to record or retain this information. When a person

conducts business, he often leaves a record.

B. Requiring accused to produce a Copy of Encrypted Data

Did Not Violate Privilege against Self-Incrimination under

Article 20(3)

Appellant argues that requiring him to produce an unencrypted

copy of the computers hard drive violated his privilege against self-

incrimination because it required him to give law enforcement

incriminating information to which they would not otherwise have

access. the District Court did not have error in requiring Appellant to

decrypt the computers hard drive because the contents of the hard drive

were not testimonial and Appellants control of the laptop and the

existence of incriminating records on the laptop were a foregone

conclusion.

.First, the contents of the computers hard drive were not

testimonial, and thus not constitutionally privileged, because the

contents were voluntarily compiled. If the party asserting privilege has

voluntarily compiled the document, no compulsion is present and the

contents of the document are not privileged..Moreover, the district

courts order, which required Appellant to produce a decrypted version

of the hard drive, did not require Appellant to restate, repeat, or affirm

the truth of the contents of the documents sought.

Appellant argues that the very act of production implies certain

incriminating facts, namely, that he had ownership and control over the

incriminating documents and that he knew of their presence. By

producing documents in compliance with a subpoena, the witness would

admit that the papers existed, were in his possession or control, and were

authentic. However, this theory does not prevent production because the

defendants possession and control of the computer was already known

a foregone conclusionas was the existence of incriminating

documents on the computer hard drive.

The computer was seized during a police raid of the

methamphetamine laboratory. lightman testified that Appellant

repeatedly used the computer and would look back at it to retrieve

information about the drug operations, to monitor the influx of

chemicals from suppliers, and to monitor the laboratories outputs. Since

the existence and content of the documents were a foregone

conclusion, the Supreme Court held that production of the documents

could be compelled without violating the Article 20(3).

Moreover, the court-ordered production of a decrypted copy of the

computers hard drive was not a fishing expedition, because the hard

drive was known to contain the information the government sought.

Here, however, the government seeks no such broad, burdensome

discovery in the hopes of uncovering new, incriminating evidence.

Rather, the government is seeking access to a hard drive when it knows,

by virtue of testimony by a co-conspirator in addition to circumstantial

evidence, that the hard drive contains extensive documentation about the

scope and operation of the moving methamphetamine laboratories.

Appellant mistakenly reads the foregone conclusion doctrine to

mean that so long as the government is not aware of all the incriminating

content on the hard drive, the contents and possession of incriminating

information are not a foregone conclusion. First, in this case, the

government knew more than that the drives might have incriminating

informationthe government had testimony to that effect. Second, it

was enough for the government to know that the defendant possessed

and controlled incriminating documents, and that the governments

request was tailored to the production of the documents that they knew

existed.

In line with this precedent, the district court was correct to hold

that the Article 20(3) does not prevent compelled decryption when it is

clear that the defendant owns and controls a computer that contains

incriminating evidence.

I. The Cell Site Location Data That Was Gathered Without a

Warrant Should Have Been Suppressed

A. Reasonable Expectation of Privacy

Though the majority correctly noted that the key to Fourth

Amendment analysis is to determine nature of the specific activity at

issue, it incorrectly applied the law. At issue is not whether the

Appellant has a reasonable expectation of privacy in Verizons historical

CSLI records, but whether he has a reasonable expectation of privacy in

the sum of his movements, as tracked by his cell phones connection to

nearby towers. Individuals may have a reasonable expectation of privacy

in the sum of their public movements even though the government has

the ability to collect aggregated GPS data.

The Supreme Court case establishing the law regarding a persons

reasonable expectation of privacy, individuals have a reasonable

expectation of privacy in their private telephone calls. Holding bears

even greater significance today, due to the sheer universality of phone

use. According to one poll, nearly three-quarters of smart phone users

report being within five feet of their phones most of the time, with 12%

admitting that they even use their phones in the shower. This reality

demands that the Court carefully consider the effects of its holding. The

Court should not take lightly the privacy interest cell phones users have,

as this decision will have far-reaching effectsinto the pockets of nearly

every Amostrian today.

The Supreme Court has considered and issued a warning regarding

the issue presented in this case. The historic location information created

by cellular phones can reconstruct someones specific movements

down to the minute, not only around town but also within a particular

building). Particular attention should be given to location monitoring

that generates a precise, comprehensive record of a persons public

movements. The time has come when the Court must decide the issue

not presented in that case: whether the government should be allowed to

use historic cell phone location information to track the minute-by-

minute movements of an individual. So there is a clear violation of

Article 21 of the Constitution.

Third Party Doctrine

.

The third party doctrine is not a full-on exception to the

legitimate-expectation of privacy inquiry. Rather, the third party

doctrine merely aids the court . . . in deciding whether certain privacy

expectations are reasonable by societal standards. Indeed, the Supreme

Court in held that an individual can expose information to the public and

retain his/her reasonable expectation of privacy in the information.

people have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their private

telephone conversations, despite using a public telephone booth and a

telephone companys routing connection of the call.

The determination as to whether an individual can retain a privacy

expectation in information, despite conveyance to a third party, turns on

how the information was conveyed and what information was conveyed.

1. Voluntariness

A person must disclose information voluntarily to a third party in

order to lose their privacy interest in the information, Mere disclosure is

not enough. If a person does not voluntarily convey the information,

then they can still retain their privacy interest in it.

Cell phone users maintain their privacy interest in their CSLI

because they do not voluntarily convey it to their service providers

finding that, though users convey their CSLI to third parties, they do not

always do so voluntarily through active participation. Voluntary

conveyance necessarily includes some amount of active participation by

the individual conveying the information. This active participation is

not always present in the creation of CSLI, which is automatically

generated when a call or message is made or received by a cell phone,

even when the user does not answer that communication. This lack of

active participation distinguishes CSLI from the existing district court

applying the third party doctrine to voluntary conveyances The claim

that users voluntarily choose to carry and use a cell phone holds little

weight, since it is idle to speak of assuming risks in contexts where,

This cannot be the rightful outcome.

2. Content Information

In going to the second inquiry, an individual can retain their

privacy interest in information conveyed to third parties depending on

the type of information conveyed. Courts do not find a privacy

expectation in third parties business records of addressing or routing

information. However, courts find that content information, though

conveyed through a third party business, can retain its privacy interest.

CSLI cannot be classified as addressing or routing information,

since it does more than route a callit tracks a users location. In fact,

it does so quite precisely. This level of detail creates the type of

sensitive content information that courts find to be protected. The

content inquiry cannot begin and end with a single data point of CSLI.

The government collects this information with respect to days and

months at a time. The amalgamation of CSLI provides a comprehensive

map of an individuals movements for that period of time.

The intimacy of the content information conveyed through

historical CSLI is compounded where, as in this case, it reveals

Appellants movements to, from, and inside his personal residence. It is

undisputed that Appellants CSLI conveyed his movements from his

home to various other locations for more than a year. As such, historical

CSLI deserves protection under Article20 (3).

If the government wishes to conduct this type of surveillance

legitimately under Article 21, it must get a warrant. Cell phone users

have a legitimate privacy interest in their historical CSLI. As such,

when the government obtains this information without a warrant, it

conducts an unreasonable search in violation of the Article 21.

I. Forcing Appellant to Produce Incriminating Records

Violated the Fifth Amendment

Forcing a defendant to decrypt and turn over documents proving

his involvement in a criminal enterprise does not violate hisprivilege

against self-incrimination. I respectfully dissent from such a holding,

since it contravenes both the meaning and spirit of the Fifth Amendment.

First, it is clear that ordering a defendant to decrypt computer files

is a testimonial compulsion, since by decrypting and producing

documents on a computer a defendant is forced to implicitly . . .

acknowledge that he has ownership and control of the computers and

their contents.

Second, the District Court misapplies, the foregone conclusion

doctrine, which was only meant to permit compulsions that would

otherwise be testimonial when the defendant adds little or nothing to

the sum total of the Governments information by conceding that he in

fact has the requested documents.It is not enough that the defendant is

suspected of possessing incriminating records, the government must

know with reasonable particularity what documents the defendant

possesses.

Here, the government suspected, but did not know, that Appellant

controlled the computer seized in the raid of the methamphetamine

laboratory. Moreover, the government suspected that the computer

contained incriminating information, but the government did not know

how much information there was nor in what form that information was

stored. Rather, the government requested that the entire hard drive be

decrypted so that they could search its files with the hope of finding

additional incriminating evidence. It was therefore error for the District

Court to hold that the existence of the incriminating documents was a

foregone conclusion. However, is a far cry from this case, in which all

the prosecution had was the word of a co-conspiratorwho was offered

less jail time in return for incriminating the defendant. Moreover, all the

co-conspirator could claim was that he saw Appellant with a computer

and that Appellant looked at his computer when accessing records. Even

if the co-conspirator is to be believed, the co-conspirator did not even

see the documents, or know what they looked like, or how many of them

there were, or even that they conclusively existed.

Likewise, the broad court order in this caseis requiring Appellant

to produce decrypted versions of all contents on the computer, including

all records, logs, or documents relating to and used in the

methamphetamine schemeendorses the prosecutors fishing

expedition for incriminating documents. Any responsive answer

Appellant could provide would necessarily be incriminating.

Given the circumstances, the court held that the facts that would

be conveyed by the defendant through his act of decryptionhis

ownership and control of the computers and their contents, knowledge of

the fact of encryption, and knowledge of the encryption keyalready

are known to the government and, thus, are a foregone conclusion.

Here, the defendant has not taunted law enforcement by claiming

that he knows how to decrypt the computer seized in the raid of the

methamphetamine laboratory, nor has he established that the computer

has records of the multiple labs operations

The government merely knew that the encrypted drives were

capable of storing vast amounts of data, some of which may be

incriminating, and that was not enough to render the contents of a hard

drive a foregone conclusion.

It is error for District Court to read the foregone conclusion

cases so broadlyin doing so, the District Court reduces the privilege

under Article 20(3) to a presumption of innocence. Under the District

Courts decision, once anyone testifies that the defendant is in

possession of incriminating information, he may be forced to decrypt

and turn over all incriminating materials related to that accusation.

Thus, the defendant is effectively forced to admit guilt and knowledge of

guilt. Thus requiring such incriminating evidence is a clear violation of

Article 20(3).

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Module 1 ComputerDokument30 SeitenModule 1 ComputerashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- EnglishDokument4 SeitenEnglishashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Computer Network - KLCDokument46 SeitenComputer Network - KLCashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- MS WordDokument15 SeitenMS WordashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Module 5Dokument29 SeitenModule 5ashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Detail Information URATPG 2019Dokument5 SeitenDetail Information URATPG 2019ashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Project On CitizenshipDokument18 SeitenProject On CitizenshipashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- MS Word - KLCDokument15 SeitenMS Word - KLCashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Anson's Law On Contract: Dawsons LTD V Bonnin (1922) 2 AC 413, 422 (Lord Haldane)Dokument1 SeiteAnson's Law On Contract: Dawsons LTD V Bonnin (1922) 2 AC 413, 422 (Lord Haldane)ashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- University of Rajasthan Admission Test For Postgraduate Courses (URATPG) 2019Dokument8 SeitenUniversity of Rajasthan Admission Test For Postgraduate Courses (URATPG) 2019ashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Lien On Shares PushpendraDokument5 SeitenLien On Shares PushpendraashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Voice Recorded in A Tape Recorder or Phone Is Admissible in EvidenceDokument4 SeitenVoice Recorded in A Tape Recorder or Phone Is Admissible in EvidenceashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Presidents of India and The Controversies They Got Into: S RadhakrishnanDokument10 SeitenPresidents of India and The Controversies They Got Into: S RadhakrishnanashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Academic Year 2016-2017: S.S. Jain Subodh Law CollegeDokument1 SeiteAcademic Year 2016-2017: S.S. Jain Subodh Law CollegeashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- ShekharDokument10 SeitenShekharashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Rape Law in IndiaDokument33 SeitenRape Law in IndiaashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Child Labour in India: ConsequencesDokument13 SeitenChild Labour in India: ConsequencesashishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Police Intelligence 2020 Version 2Dokument154 SeitenPolice Intelligence 2020 Version 2Kristine Ville BathanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Housekeeping 3rd QRTR LasDokument4 SeitenHousekeeping 3rd QRTR LasKristelle Dee MijaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Murex Services FactsheetDokument16 SeitenMurex Services FactsheetG.v. AparnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- User Manual - Camera Video SanyoDokument19 SeitenUser Manual - Camera Video Sanyoanak1n888Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1091)

- IP200 Installation User GuideDokument34 SeitenIP200 Installation User GuideVodafone Business SurveillanceNoch keine Bewertungen

- A.Parveen Banu: T-Warehouse: Visual Olap Analysis On Trajectory DataDokument13 SeitenA.Parveen Banu: T-Warehouse: Visual Olap Analysis On Trajectory Datapri03Noch keine Bewertungen

- Def of Terms in CriminalisticsDokument6 SeitenDef of Terms in CriminalisticsMark Nayre BusaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Countersurveillance GuidelinesDokument4 SeitenCountersurveillance GuidelinesKudos AmasawaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cisco Video Surveillance 6900 Series High Definition PTZ IP CameraDokument7 SeitenCisco Video Surveillance 6900 Series High Definition PTZ IP CameraRenu MahorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rio Grande Case AnalysisDokument6 SeitenRio Grande Case AnalysisMary Rose Dionisio100% (2)

- J. Truscott, OAM - The Art of Crisis Leadership Incident Management in The Digital Age PDFDokument138 SeitenJ. Truscott, OAM - The Art of Crisis Leadership Incident Management in The Digital Age PDFMarta DrčićNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

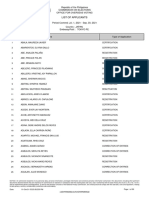

- List of Applicants 20210701 0930Dokument107 SeitenList of Applicants 20210701 0930Rovern Keith Oro CuencaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TAM Poster v15 5Dokument1 SeiteTAM Poster v15 5Diego GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IMOUSEDokument21 SeitenIMOUSEAkhil BhargavNoch keine Bewertungen

- DatabaseDokument17 SeitenDatabaseMagnolia Garcia HermosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Top Tips For Monitoring Algo Trading - Eventus SystemsDokument6 Seiten12 Top Tips For Monitoring Algo Trading - Eventus Systemssimha1177Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mspo TraceDokument33 SeitenMspo TraceAl IkhwanNoch keine Bewertungen

- PBL ProjhbghDokument4 SeitenPBL ProjhbghKaushal PathakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Losa Icao Doc 9803Dokument58 SeitenLosa Icao Doc 9803partyman_my100% (1)

- Secretly Forced Brain Implants PT 1 - Explosive Court Case - EXAMINER ARTICLEDokument9 SeitenSecretly Forced Brain Implants PT 1 - Explosive Court Case - EXAMINER ARTICLERally The People100% (2)

- Zksoftware Product CatalogDokument32 SeitenZksoftware Product Cataloglinuxserver500Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teachers Book Solutions IntermediateDokument8 SeitenTeachers Book Solutions IntermediateDuong Nguyen75% (12)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- 8 - Team Excalibur, Shepherd Deal With EWOS PDFDokument2 Seiten8 - Team Excalibur, Shepherd Deal With EWOS PDFBrobin101Noch keine Bewertungen

- Strahlenfolter - I'm A Targeted Individual - YoutubeDokument6 SeitenStrahlenfolter - I'm A Targeted Individual - YoutubeFred_BlankeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ranger r3 DatasheetDokument2 SeitenRanger r3 DatasheetSaurabh MelveettilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Networks (Gategyan In)Dokument50 SeitenNetworks (Gategyan In)Vijayakumar SNoch keine Bewertungen

- 24H 1D RP 5.000 24H 1D RP 5.000 24H 1D RP 5.000: (1) Parnawifi (2) Parnawifi (3) ParnawifiDokument5 Seiten24H 1D RP 5.000 24H 1D RP 5.000 24H 1D RP 5.000: (1) Parnawifi (2) Parnawifi (3) Parnawifiadrian simbolonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employee Monitoring and Management System Using GPS and AndroidDokument5 SeitenEmployee Monitoring and Management System Using GPS and AndroidAnonymous kw8Yrp0R5r100% (1)

- Effectiveness of CCTV Against CrimeDokument12 SeitenEffectiveness of CCTV Against CrimeDale Daloma DalumpinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jitendra Hariramani: Skills & ExpertiseDokument5 SeitenJitendra Hariramani: Skills & ExpertiseAtifIqbalKidwaiNoch keine Bewertungen