Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

2017/3/6 ӥ܌11) 07 Einstein as a Jew and a Philosopher - by Freeman Dyson - The New York Review of Books

Hochgeladen von

CherryOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

2017/3/6 ӥ܌11) 07 Einstein as a Jew and a Philosopher - by Freeman Dyson - The New York Review of Books

Hochgeladen von

CherryCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Einstein as a Jew and a Philosopher | by Freeman Dyson | The New York Review of Books 2017/3/6 11)07

Abolition was for him the only way to save mankind from the threat of nuclear destruction. He was not sure how abolition

could be achieved. Sometimes he spoke of a world government with power to stop nuclear activities in every country.

Sometimes he spoke of formal agreements between existing governments. Sometimes he spoke about abolishing war as

well as abolishing nuclear weapons. He understood that any abolition of war or of weapons would require a radical change

in our way of thinking.

The essential first step, before any abolition agreement could be effective, was to educate the public. The public and the

political leaders must understand that nuclear weapons were not only intolerably dangerous but also militarily useless.

Once these facts of life were clearly understood, there would be a fighting chance that an abolition agreement could work.

Einstein did whatever he could in his final years to educate the public.

In the last month of his life, he joined with Bertrand Russell to make a public statement that he did not live to see

published. Here are its concluding words:

In view of the fact that in any future world war nuclear weapons will certainly be employed, and that such weapons

threaten the continued existence of mankind, we urge the Governments of the world to realize, and to acknowledge

publicly, that their purposes cannot be furthered by a world war, and we urge them, consequently, to find peaceful

means for the settlement of all matters of dispute between them.

After the Russell-Einstein manifesto was published, there grew out of it an organization called the Pugwash movement,

bringing together scientists from East and West to discuss the problems of war and weapons. The name Pugwash came

from the small town in eastern Canada where the first meeting was held in 1957. Since that time, meetings have been held

in many countries, continuing up to the present day. The basic idea of the meetings is that science gives to scientists of all

countries a common language, so that they can understand one another even when talking about political and human

problems having little to do with science.

Politicians and diplomats have much greater difficulty in understanding one another. Scientists have long experience of

working together in an international enterprise that pays no attention to national or ideological differences. At the

beginning, Bertrand Russell himself presided over the Pugwash meetings. After Russell retired, the leadership was taken

over by Joseph Rotblat, a Polish nuclear physicist who worked at Los Alamos and became famous as the only scientist who

walked out of Los Alamos for reasons of conscience in 1944, when it became known that Germany did not have a serious

nuclear weapons project. General Leslie Groves let him go after he promised not to tell his friends the reason for his

departure. Rotblat ran the Pugwash meetings for forty years. He won the respect of all the participants and many of their

governments.

I attended several of the early Pugwash meetings under the auspices of Russell and Rotblat. At that time they were acting

as a valuable back channel for exchanging views between the American and Soviet governments, when the official

diplomatic channel was blocked by ideological disagreements. The two dominant personalities were Le Szilrd on the

American side and Vladimir Pavlichenko on the Soviet side. Szilrd was an old friend of Einstein from Einsteins Berlin

days. He wrote the letter that Einstein signed in 1939, warning President Roosevelt that nuclear weapons were a possibility,

that uranium was the crucial material for their manufacture, and that it was important to keep the rich uranium ores of the

Belgian Congo out of the hands of Hitler.

Szilrd had also tried in vain to deliver an appeal to President Truman in 1945, urging him to give Japan warning and an

opportunity to surrender before dropping nuclear bombs on Japanese cities. Pavlichenko was the KGB man on the Soviet

side, sent to Pugwash conferences along with the scientists to make sure that they did not deviate from the Soviet line. He

was highly intelligent and well informed about technical and political questions. He knew far more than the scientists about

the actions and intentions of his own government.

Szilrd immediately recognized Pavlichenko as the man to talk to when serious issues were discussed. Any proposal made

to Pavlichenko would reach high levels in the Soviet government. Szilrd had friends at high levels in the American

government, and so this unlikely pair, the Hungarian rebel and the KGB apparatchik, worked fruitfully together to carry

messages in both directions. Now, fifty years later, Pugwash meetings are carrying messages between Israel and hostile

Arab states in the Middle East, and between India and Pakistan in Asia. The hope expressed by Einstein is still alive, that

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2015/05/07/albert-einstein-jew-and-philosopher/"printpage=true 3/5

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Peaceful Protests: Voices for Peace: Jane Adams, Muhammad Ali, John Lennon, Leymah GboweeVon EverandPeaceful Protests: Voices for Peace: Jane Adams, Muhammad Ali, John Lennon, Leymah GboweeNoch keine Bewertungen

- CAN WE SAVE THE PLANET FROM THE HOLOCAUST OF THE WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION?Von EverandCAN WE SAVE THE PLANET FROM THE HOLOCAUST OF THE WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION?Noch keine Bewertungen

- Unofficial peace diplomacy: Private peace entrepreneurs in conflict resolution processesVon EverandUnofficial peace diplomacy: Private peace entrepreneurs in conflict resolution processesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Toward a Theory of Peace: The Role of Moral BeliefsVon EverandToward a Theory of Peace: The Role of Moral BeliefsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Riddle, Mystery, and Enigma: Two Hundred Years of British–Russian RelationsVon EverandRiddle, Mystery, and Enigma: Two Hundred Years of British–Russian RelationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jordan Schneider Pasvolsky Webster Thesis FinalDokument73 SeitenJordan Schneider Pasvolsky Webster Thesis FinalRobert Alston100% (1)

- Democracy's Muse: How Thomas Jefferson Became an FDR Liberal, a Reagan Republican, and a Tea Party Fanatic, All the While Being DeadVon EverandDemocracy's Muse: How Thomas Jefferson Became an FDR Liberal, a Reagan Republican, and a Tea Party Fanatic, All the While Being DeadBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Countdown 1945: The Extraordinary Story of the Atomic Bomb and the 116 Days That Changed the World by Chris Wallace and Mitch Weiss: Conversation StartersVon EverandCountdown 1945: The Extraordinary Story of the Atomic Bomb and the 116 Days That Changed the World by Chris Wallace and Mitch Weiss: Conversation StartersNoch keine Bewertungen

- In the Words of Theodore Roosevelt: Quotations from the Man in the ArenaVon EverandIn the Words of Theodore Roosevelt: Quotations from the Man in the ArenaBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (1)

- The Hawk and the Dove: Paul Nitze, George Kennan, and the History of the Cold WarVon EverandThe Hawk and the Dove: Paul Nitze, George Kennan, and the History of the Cold WarBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Updated EditionVon EverandThe Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Updated EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness: A Vindication of Democracy and a Critique of Its Traditional DefenseVon EverandThe Children of Light and the Children of Darkness: A Vindication of Democracy and a Critique of Its Traditional DefenseBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (1)

- Gun Control in the Third Reich: Disarming the Jews and "Enemies of the State"Von EverandGun Control in the Third Reich: Disarming the Jews and "Enemies of the State"Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (7)

- Du Bois’s Telegram: Literary Resistance and State ContainmentVon EverandDu Bois’s Telegram: Literary Resistance and State ContainmentBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Super Bomb: Organizational Conflict and the Development of the Hydrogen BombVon EverandSuper Bomb: Organizational Conflict and the Development of the Hydrogen BombNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opening NATO's Door: How the Alliance Remade Itself for a New EraVon EverandOpening NATO's Door: How the Alliance Remade Itself for a New EraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes and Where It Comes FromVon EverandConspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes and Where It Comes FromBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (4)

- The Nazi Seizure of Power: The Experience of a Single German Town, 1922-1945Von EverandThe Nazi Seizure of Power: The Experience of a Single German Town, 1922-1945Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (44)

- Pugwash and Bertrand Russell's Legacy by J LenzDokument8 SeitenPugwash and Bertrand Russell's Legacy by J LenzJohnRLenzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roosevelt and the Russians: The Yalta ConferenceVon EverandRoosevelt and the Russians: The Yalta ConferenceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secret Wars and Secret Policies in the Americas, 1842-1929Von EverandSecret Wars and Secret Policies in the Americas, 1842-1929Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hope and Destiny: Truman, Eisenhower, Fulbright, and US Foreign Policy in the Middle East, 1945-1958Von EverandHope and Destiny: Truman, Eisenhower, Fulbright, and US Foreign Policy in the Middle East, 1945-1958Noch keine Bewertungen

- Churchill and Roosevelt: A Captivating Guide to the Life of Franklin and WinstonVon EverandChurchill and Roosevelt: A Captivating Guide to the Life of Franklin and WinstonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eisenhower and Latin America: The Foreign Policy of AnticommunismVon EverandEisenhower and Latin America: The Foreign Policy of AnticommunismNoch keine Bewertungen

- Countering Mainstream Narratives: Fake News, Fake Law, Fake FreedomVon EverandCountering Mainstream Narratives: Fake News, Fake Law, Fake FreedomNoch keine Bewertungen

- American Radical: The Life and Times of I. F. StoneVon EverandAmerican Radical: The Life and Times of I. F. StoneBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Alger Hiss: Framed: A New Look at the Case That Made Nixon FamousVon EverandAlger Hiss: Framed: A New Look at the Case That Made Nixon FamousNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democracy's Think Tank: The Institute for Policy Studies and Progressive Foreign PolicyVon EverandDemocracy's Think Tank: The Institute for Policy Studies and Progressive Foreign PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Wilson Administration and Civil Liberties, 1917-1921Von EverandThe Wilson Administration and Civil Liberties, 1917-1921Noch keine Bewertungen

- Deadly Contradictions: The New American Empire and Global WarringVon EverandDeadly Contradictions: The New American Empire and Global WarringNoch keine Bewertungen

- I Must Resist: Bayard Rustin's Life in LettersVon EverandI Must Resist: Bayard Rustin's Life in LettersBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (2)

- Dreams for a Decade: International Nuclear Abolitionism and the End of the Cold WarVon EverandDreams for a Decade: International Nuclear Abolitionism and the End of the Cold WarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Our Stage: The Global Rhetorical Presidency and the Cold WarVon EverandThe World Is Our Stage: The Global Rhetorical Presidency and the Cold WarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard RustinVon EverandLost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard RustinBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (19)

- Development Against Democracy: Manipulating Political Change in the Third WorldVon EverandDevelopment Against Democracy: Manipulating Political Change in the Third WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Not a Movement of Dissidents: Amnesty International Beyond the Iron CurtainVon EverandNot a Movement of Dissidents: Amnesty International Beyond the Iron CurtainNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of ReaganVon EverandThe Other Eighties: A Secret History of America in the Age of ReaganNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Secret History of The Atomic Bomb by Eustace CDokument18 SeitenThe Secret History of The Atomic Bomb by Eustace CbandrigNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nazi Ideology before 1933: A DocumentationVon EverandNazi Ideology before 1933: A DocumentationBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Albert Einstein, The Human Side: Glimpses from His ArchivesVon EverandAlbert Einstein, The Human Side: Glimpses from His ArchivesBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (7)

- Profession of Conscience: The Making and Meaning of Life-Sciences LiberalismVon EverandProfession of Conscience: The Making and Meaning of Life-Sciences LiberalismNoch keine Bewertungen

- Churchill and the Jews: A Lifelong FriendshipVon EverandChurchill and the Jews: A Lifelong FriendshipBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (10)

- The A-Bomb PDFDokument32 SeitenThe A-Bomb PDFcamiloNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Blueprint for War: FDR and the Hundred Days that Mobilized AmericaVon EverandA Blueprint for War: FDR and the Hundred Days that Mobilized AmericaBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- The Paranoid Apocalypse - A Hundred-Year Retrospective On The Protocols of The Elders of Zion (PDFDrive)Dokument273 SeitenThe Paranoid Apocalypse - A Hundred-Year Retrospective On The Protocols of The Elders of Zion (PDFDrive)Setyo Prabowo100% (2)

- Ride of Kwame Nkrumah at BandungDokument36 SeitenRide of Kwame Nkrumah at BandungSri Widagdo Purwo ArdyasworoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Anglo-Venetian Descent Into BarbarismDokument2 SeitenThe Anglo-Venetian Descent Into BarbarismisherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schiller Institute: How Bertrand Russell Became An Evil ManDokument30 SeitenSchiller Institute: How Bertrand Russell Became An Evil ManGregory HooNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017/3/6 ӥ܌11) 07 Einstein as a Jew and a Philosopher - by Freeman Dyson - The New York Review of BooksDokument2 Seiten2017/3/6 ӥ܌11) 07 Einstein as a Jew and a Philosopher - by Freeman Dyson - The New York Review of BooksCherryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problem 7.4: (A) Follow The Proof inDokument1 SeiteProblem 7.4: (A) Follow The Proof inCherryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problem 2.52: (A) (1) From Eq. 2.133: F + G A + BDokument1 SeiteProblem 2.52: (A) (1) From Eq. 2.133: F + G A + BCherryNoch keine Bewertungen

- D D L D L DX G B B DT DT DT DT D B DT L D L DT D D D DX G B B B DT DT DT DTDokument1 SeiteD D L D L DX G B B DT DT DT DT D B DT L D L DT D D D DX G B B B DT DT DT DTCherryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Is There Anything at All? 101Dokument1 SeiteWhy Is There Anything at All? 101CherryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Confucianism. London: Arthur Probsthain, 1927Dokument1 SeiteAncient Confucianism. London: Arthur Probsthain, 1927CherryNoch keine Bewertungen

- → cf.儀禮,典章制度 →cf.「magic power」 (Herbert Fingarette) : Li (….) bring out forcefully not only the harmony andDokument1 Seite→ cf.儀禮,典章制度 →cf.「magic power」 (Herbert Fingarette) : Li (….) bring out forcefully not only the harmony andCherryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On A World of States of Affairs (1997) : 2.32 Partial IdentityDokument1 SeiteNotes On A World of States of Affairs (1997) : 2.32 Partial IdentityCherryNoch keine Bewertungen

- note 部分3Dokument1 Seitenote 部分3CherryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On A World of States of Affairs (1997)Dokument1 SeiteNotes On A World of States of Affairs (1997)CherryNoch keine Bewertungen

- note 部分2Dokument1 Seitenote 部分2CherryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lite Touch. Completo PDFDokument206 SeitenLite Touch. Completo PDFkerlystefaniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SEx 3Dokument33 SeitenSEx 3Amir Madani100% (4)

- CRM - Final Project GuidelinesDokument7 SeitenCRM - Final Project Guidelinesapi-283320904Noch keine Bewertungen

- GN No. 444 24 June 2022 The Public Service Regulations, 2022Dokument87 SeitenGN No. 444 24 June 2022 The Public Service Regulations, 2022Miriam B BennieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conversation Between God and LuciferDokument3 SeitenConversation Between God and LuciferRiddhi ShahNoch keine Bewertungen

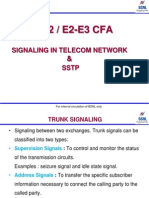

- Signalling in Telecom Network &SSTPDokument39 SeitenSignalling in Telecom Network &SSTPDilan TuderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poet Forugh Farrokhzad in World Poetry PDokument3 SeitenPoet Forugh Farrokhzad in World Poetry Pkarla telloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ergatividad Del Vasco, Teoría Del CasoDokument58 SeitenErgatividad Del Vasco, Teoría Del CasoCristian David Urueña UribeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Java ReviewDokument68 SeitenJava ReviewMyco BelvestreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exercise 1-3Dokument9 SeitenExercise 1-3Patricia MedinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MINIMENTAL, Puntos de Corte ColombianosDokument5 SeitenMINIMENTAL, Puntos de Corte ColombianosCatalina GutiérrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- WO 2021/158698 Al: (10) International Publication NumberDokument234 SeitenWO 2021/158698 Al: (10) International Publication Numberyoganayagi209Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hercules Industries Inc. v. Secretary of Labor (1992)Dokument1 SeiteHercules Industries Inc. v. Secretary of Labor (1992)Vianca MiguelNoch keine Bewertungen

- FJ&GJ SMDokument30 SeitenFJ&GJ SMSAJAHAN MOLLANoch keine Bewertungen

- A&P: The Digestive SystemDokument79 SeitenA&P: The Digestive SystemxiaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abnormal PsychologyDokument13 SeitenAbnormal PsychologyBai B. UsmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- AASW Code of Ethics-2004Dokument36 SeitenAASW Code of Ethics-2004Steven TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fansubbers The Case of The Czech Republic and PolandDokument9 SeitenFansubbers The Case of The Czech Republic and Polandmusafir24Noch keine Bewertungen

- Types of Numbers: SeriesDokument13 SeitenTypes of Numbers: SeriesAnonymous NhQAPh5toNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Midterm ExamDokument6 SeitenSample Midterm ExamRenel AluciljaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2023-Tutorial 02Dokument6 Seiten2023-Tutorial 02chyhyhyNoch keine Bewertungen

- ObliCon Digests PDFDokument48 SeitenObliCon Digests PDFvictoria pepitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leg Res Cases 4Dokument97 SeitenLeg Res Cases 4acheron_pNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 - Risk Assessment ProceduresDokument40 SeitenChapter 4 - Risk Assessment ProceduresTeltel BillenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Radio Network Parameters: Wcdma Ran W19Dokument12 SeitenRadio Network Parameters: Wcdma Ran W19Chu Quang TuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diode ExercisesDokument5 SeitenDiode ExercisesbruhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affirmative (Afirmativa) Long Form Short Form PortuguêsDokument3 SeitenAffirmative (Afirmativa) Long Form Short Form PortuguêsAnitaYangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developing Global LeadersDokument10 SeitenDeveloping Global LeadersDeepa SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reflection On Harrison Bergeron Society. 21ST CenturyDokument3 SeitenReflection On Harrison Bergeron Society. 21ST CenturyKim Alleah Delas LlagasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Robot MecanumDokument4 SeitenRobot MecanumalienkanibalNoch keine Bewertungen