Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Ceremonial Function of Markets in The Timurid City

Hochgeladen von

nirvaang0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

10 Ansichten8 SeitenCeremonial Function of Markets in the Timurid City

Originaltitel

Ceremonial Function of Markets in the Timurid City

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCeremonial Function of Markets in the Timurid City

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

10 Ansichten8 SeitenCeremonial Function of Markets in The Timurid City

Hochgeladen von

nirvaangCeremonial Function of Markets in the Timurid City

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 8

THE CEREMONIAL FUNCTION

OF MARKETS IN THE TIMURID CITY

In 1950, on the basis of a description by Ruy

Gonzalez de Clavijo, Ratija reconstructed

‘one of the great shopping streets ran through

‘Samarkand from its boundary walls to the

city centre.

Clavijo’s describes Timur’s_ (Tamerlane’s)

need to create a solemn (official) place in

which goods from Tartary, India and China,

as well as from other parts of his empire,

could be sold in proper fashion. The avenue

was designed with shops on both sides with

counters lined with white tiles, and with foun-

tains at regular intervals. Due to this cons-

truction programme, the former inhabitants

of the buildings destroyed ruthlessly to make

room for the new constructions and for the

‘merchants to be installed in them were turn-

ed out, and so complained, via intermedia-

ries, to Tamerlane. Tamerlane was furious

and’ answered in singular fashion that: “This

city is mine. | bought it with my own money

and I have written proof which | will show you

tomorrow, and if you are in the right | will pay

you what 'you ask.”?

Of Ratija's reconstruction, which however is

hypothetical, as the author himself recogn-

izes, no trace remains today, although in the

ninth century, that system of six roads con-

verging on the city centre was still seen and,

described by many authors? Whatsoever

there are various points of interest in Clavi-

jo’s account. First and foremost, Tamerla-

1ne’s will to implement systematically a monu-

mental building “programme” in which the

markets play a significant role. This will

clearly stemmed from the necessity to settle

artisans and traders from every part of the

Tamerisne’s ecumene, so that Samarkand

would become a metropolis able to stand

against the other great cities of the time,

such as Cairo and Damascus.« What strikes

us about Clavijo's description is the answer

to those who asked for compensation for the

inhabitants turned out of their homes; the

sovereign in fact stated that he was the

“owner” of the city and that he possessed

documents certifying this. Another interest-

ing feature of Clavijo's account regards the

way the shops were arranged on both sides

of the street and were designed with two

rooms, one probably intended for sales ope-

rations, in which the marble counter stood,

and the other for other uses, perhaps a store

‘or a workshop. At intervals, moreover, the

“design” of the street contemplated foun-

tains.

We will be returning later to these aspects of

Clavijo’s description, but here Iwould like to

underline function of these commercial

streets: that of ceremony. In this respect itis

worth noting that already before 1404, the

year of Clavijo's description, Tamerlane and

his aristocracy used the porticoed, shop-

fronted avenues for their triumphant proces-

sions on their return from military victories or

‘on the occasion of public celebrations, as,

for example, marriages. The use of markets

in this sense is not new, and we find it in Fati-

mid Cairo as described by Naser-e Khos-

row:

“In the year 439 [AD 1047] the sultan ordered

general rejoicing for the birth of a son: the

city and bazaars were so arrayed that, were

they to be described, some would not believe

that drapers’ and moneychangers’ shops

could be so decorated with gold, jewels,

coins, goldspun cloth and embroidery, that

there was no room to sit down!"»

The Persian sources for the Timurid period,

and especially the Zaferndme by Yazdi and

Sami, include similar poetic passages in-

serted in their chronicles. In 1394, for

instance, Samarkand was decked out fest-

ively to welcome Sahrox:®

*... Samarkand was decked out so festively

as to stupefy the mind; from top to bottom all

the skilled workers | (mardom-e pisavar)

showed off their respective specialities; in a

glorifiyng way 7 roads and lanes made the

city as ornate as sublime paradise; the ba-

zaars became flowery meadows with the ex-

pension of the decorations on the walls; from

‘one end of the portals to the other standards

and even caftans and belts interwoven with

gold were hoisted; from the gate of the city

all the way to the sovereign’s residence

purple fabrics and satin cloths were cast

over the streets; the whole city was an image

of gold and ornaments; gold and silver were

scattered at the horses’ feet. "=

In 1396, on his return from Hamadan, Tamer-

lane entered a Samarkand richly decorated

for the occasion:

“They decorated the world with joy, they

brought forth musicians from everywhere

(rémesgaran); the scattered pearls formed a

mantle on the face of the earth and the whole

city was an image of golden ornament; many

crossroads (cértaq) heaped with decorations

were the envy of a Nile of porticoes (Nil-e

revéq); a decoration was arranged on every

Portico and under it, at every corner, some

musicians; the whole realm had become em:

bellishment: the doors, the walls and the ter-

races were filled with decorations, and even

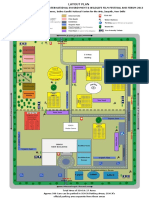

TION OF THE SAMARKAND COMMERCIAL AREA

in the lanes and in the markets the walls were

adorned with decorations; the craftsmen had

decked out all the bazaars from one end to

the other. Silks and brocades were strewn

over the whole road, and over them (passed)

the (royal) horses’ hooves. The gold

spangled with silver and the interwoven

decorations covered the surface of the whole

district; left and right, above and below, no-

thing was visible that was not of splendid

shape.”*

Similar celebrations are described in the

commentary to Sami's Zaferndme, in which

circumstance the orate, festive city was

Herat, with a wedding procession in 1379.

For the occasion Tamerlane ordered the city

to be decorated like the garden of Eram, and

ornaments were placed from the beginning

of the Juy-e Nou to the market crossroads

(cahédrsuy). All the corporations of craftsmen

(firgat az mohtarefe) were convened and

were ordered to carry out a work of extraor-

dinary skill and craft, each according to his

capacity. Doors and walls were in this way

decked with Byzantine and Chinese bro-

cades. The domes became elegant, lovely

scenes (xub manzar), and on ali sides

singers (moghanniyan) intoned songs, food

for the spirit, drink for the soul."

As in Samarkand, the commercial area of

Herat, too, was founded by Sahrox, who:

“ordered bazaars to be made of baked brick

and mortar; tall arches were built and the

roof of the bazaar covered over, with spaces

left for light; the view of the onlookers was

met by chambers (soffe) with smaller rooms

(hojre) above. The bazaar was a spectacle in

the eye of the world and a meadow in the

springtime. Its covered market (cahdr suy)

was a square with four equal sides, situated

in the centre of the circle of charitable works

(khair al-biga’). From the four gates of the

town, four roads led to that place (the chahar

su).""

The necessity to restore systematically the

Timurid markets thus seems linked to a cere-

monial function performed by the markets.

This function was certainly not new in the

Timurid period (see the passage by Naser-e

Khosrow) and reflects the need for an ‘offi

cia!’ integration of the artisan components at

important moments in the social life of the

city (weddings, circumcisions of princes,

‘celebrations of military victories). In such cir-

‘cumstances, apart from displaying the riches

of the realm, exemplary public trials or of-

ficial investitures could take place. Other

ceremonies were held outside the urban

enclosure, such as military reviews (‘arz or

este'rdz,)"* or feasts devoted to the res-

tricted circle of the family, such as those in

which Clavijo participated in the gardens out-

side of the city of Samarkand." The use of

the shop-lined avenues with a ceremonial

function was thus limited to celebrations

which - to use a terminology often adopted

by the Persians - involved the khass 0 ‘am,

namely the nobles and the populace in the

generic distinction typical of Islamic socio-

logy.

The function of the ahl-e harefe (the cratt-

smen)'* in these events calls for a number of

further historical considerations. Expanding

into the suburbs of Samarkand and rationa~

lizing them in a mercantile key, Tamerlane

encompasses the artisan components. in

what he himself calls “his property”. The pro-

cess of merging the mercantile and the

handicraft areas with the _political-

‘administrative ones is not a new fact. Aban-

doning the sahrestan had already occurred

in Samarkand as in Merv in the course of the

preceding centuries.** Cuneo has noted that

this passage coincides with the transition

from an ‘archaic’ period “with its feudal-type

organization (...) based on the supremacy of

a landowning aristocracy possessing whole

Villages and monopolizing agricultural pro-

duction and the caravan traffic, to a ‘mature’

Period which in the ninth century witnessed

the emergence of new classes (...) formed

by rich merchants and by an aristocracy of

officials and of craftsmen no longer subser-

nt to the rights of the landowners.” While

numerous market-towns designed sepa-

rately from the political-administrative cen-

tres according to the ‘archaic’ pattern (e.g.

‘Suq al-Amir, founded by the Buyid ‘Adud ad-

Dawia in the tenth century) continued to

survive, the integration of the two compo-

nents of archaic cities seems to have deve

loped further with the Seljuks.%» This period is

the climax of the artisan classes, as. wit-

nessed for example by numerous metal ob-

jects and the indications supplied by the

wealth of epigraphic material.

The enhancement of handicraft activities

may be put down to Ismailite propaganda

and more generally reflects the legitimist

Needs of a social class - the merchant craft-

‘smen class - at its height in the Seljuk era.*"

This complex problem is one of the nodal

points of the conception of the Islamic

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Design For Sustainability 2019 - 1Dokument6 SeitenDesign For Sustainability 2019 - 1nirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Principles of BiomimicryDokument6 SeitenPrinciples of BiomimicrynirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Tamples of India PDFDokument40 SeitenTamples of India PDFnirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Ignca LayoutDokument1 SeiteIgnca Layoutmahima vermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Design For Sustainability 2019Dokument15 SeitenDesign For Sustainability 2019nirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Design For Sustainability 2020 (Auto-Saved)Dokument10 SeitenDesign For Sustainability 2020 (Auto-Saved)nirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- DRM - Youtube As A Medium of Info Transfer Amongst Millennial & Post-Millennial Youth.Dokument13 SeitenDRM - Youtube As A Medium of Info Transfer Amongst Millennial & Post-Millennial Youth.nirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Indian Architecture PDFDokument12 SeitenIndian Architecture PDFnirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Design Research Methods and Perspectives PDFDokument10 SeitenDesign Research Methods and Perspectives PDFnirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Complex Field of Research: For Design, Through Design, and About DesignDokument12 SeitenThe Complex Field of Research: For Design, Through Design, and About DesignAdri GuevaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Famous India PDFDokument20 SeitenFamous India PDFnirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Demystifying "Design Research" - Design Is Not Research, Research Is Design PDFDokument8 SeitenDemystifying "Design Research" - Design Is Not Research, Research Is Design PDFJuan Manuel EscamillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interaction Design Theory & Methods PDFDokument17 SeitenInteraction Design Theory & Methods PDFnirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Design Research Methods and Perspectives PDFDokument10 SeitenDesign Research Methods and Perspectives PDFnirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Understanding French Culture Through Advertisements Networking AnDokument12 SeitenUnderstanding French Culture Through Advertisements Networking AnnirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Chi519 Zimmerman PDFDokument10 SeitenChi519 Zimmerman PDFnirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Complex Field of Research: For Design, Through Design, and About DesignDokument12 SeitenThe Complex Field of Research: For Design, Through Design, and About DesignAdri GuevaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Chi519 Zimmerman PDFDokument10 SeitenChi519 Zimmerman PDFnirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Standard Furniture DimensionsDokument1 SeiteStandard Furniture DimensionsIana LeynoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demystifying "Design Research" - Design Is Not Research, Research Is Design PDFDokument8 SeitenDemystifying "Design Research" - Design Is Not Research, Research Is Design PDFJuan Manuel EscamillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Arcuate Techniques in Palatial StructureDokument10 SeitenArcuate Techniques in Palatial StructurenirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Timber ConstructionDokument7 SeitenTimber ConstructionkennypetersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ahmedabad Declaration 1979 PDFDokument2 SeitenAhmedabad Declaration 1979 PDFnirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02 - Asterix and The Golden Sickle PDFDokument42 Seiten02 - Asterix and The Golden Sickle PDFnirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Research On Pre-Mughal Islamic Material Culture in South AsiaDokument12 SeitenNew Research On Pre-Mughal Islamic Material Culture in South AsianirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shah Jahan's Visits To Delhi Before 1648Dokument12 SeitenShah Jahan's Visits To Delhi Before 1648nirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timurid Central Asia & Mughal IndiaDokument147 SeitenTimurid Central Asia & Mughal IndianirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Wood Joints in Classical Japanese ArchitectureDokument69 SeitenWood Joints in Classical Japanese ArchitectureValerio Nicoletti100% (6)

- Chaukhandi Tombs Matricola955338 Ciclo22Dokument207 SeitenChaukhandi Tombs Matricola955338 Ciclo22nirvaangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)