Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

031

Hochgeladen von

aliceCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

031

Hochgeladen von

aliceCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

produce weapons and implements of high quality.

Blacksmiths and other craftsmen

remained the main suppliers of the rural market for tools and agricultural

implements throughout the colonial period, adapting their tech-niques to make use

of manufactured iron and scrap. From the late eighteenth century onwards

European entrepreneurs tried to improve local iron-making by splicing in isolated

pieces of British technology, such as the use of smelting coal and blast-furnaces.

The most substantial enterprise of this type was the iron works at Porto Novo in

Madras which was promoted by J. M. Heath, a former East India Company official,

with assistance from the Company and the Government of Madras in 1825. This

factory was based largely on traditional methods, using charcoal for smelting and

animal power for bellows and forging equipment. Lacking economies of scale and

the technological capacity to create a new niche in the market, it could compete

neither with imports of British coke-produced blast-furnace iron and steel nor with

the product of traditional smelters in the villages, and had ceased to be a serious

proposition long before it was finally wound up in the 187os.

The first recognisably modern iron works in India was established by the Bengal Iron

Works Company in 1874. This, too, had a chequered and largely unsuccessful

career. The company began to produce iron in 1877, but was already heavily in debt

and committed to outmoded technology, and closed down two years later. The

Government of Bengal, which had offered some sup-port in an attempt to obtain

local supplies of railway equipment, bought up the defunct firm, operated it as a

public company for a few years, and then sold the assets to a group of British

businessmen who re-established the enterprise as the Bengal Iron and Steel

Company in 1889. The new Bengal Company was again undercapitalised, and

lacked adequate information on input costs or market potentialities. The

government refused to provide subsidised loans to weather a crisis in the mid

189os, but in 1897 agreed to purchase 10,000 tonnes of iron annually (more than

half the output of the works) for ten years, at rates 5 per cent below the import

price. This agreement was not renewed in 1907, and an attempt to begin steel

production at the plant, for which the government had agreed to subsidise a rate of

return of 3 per cent for ten years, failed at the same time. In 1910 the Company got

access to new and improved supplies of ore and coal, and by the First World War

had established itself as a modest producer of iron products, mostly of pig-iron for

export; it made good profits during the war, but lacked any clear potential for

expansion thereafter except into cast-iron pipes, and ceased large-scale production

of pig-iron in 1925.

In 1918 a second iron works was founded in Bengal by the Indian Iron and Steel

Company (IISCO), which was linked to the Bengal Company through

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- 016Dokument1 Seite016aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 014Dokument1 Seite014aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 015Dokument1 Seite015aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02Dokument1 Seite02aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 016Dokument1 Seite016aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01Dokument1 Seite01aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 017Dokument1 Seite017aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 020Dokument1 Seite020aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 035Dokument1 Seite035aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 017Dokument1 Seite017aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 019Dokument1 Seite019aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 018Dokument1 Seite018aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 030Dokument1 Seite030aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 030Dokument1 Seite030aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 033Dokument1 Seite033aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 034Dokument1 Seite034aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02Dokument1 Seite02aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01Dokument1 Seite01aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ri Ep2 Biu2022Dokument11 SeitenRi Ep2 Biu2022aliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- NH 730a-Epc QueriesDokument2 SeitenNH 730a-Epc QueriesPerkresht PawarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measuring The Cost of LivingDokument42 SeitenMeasuring The Cost of Livingjoebob1230Noch keine Bewertungen

- Questionnaire: The Vals Survey (Designed For Bangladeshi People)Dokument4 SeitenQuestionnaire: The Vals Survey (Designed For Bangladeshi People)Smita NimilitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- KNIT - Berkertex 1075 - Dress, Cardigan, Bonnet, Bootees and Shawl (31-46cm)Dokument4 SeitenKNIT - Berkertex 1075 - Dress, Cardigan, Bonnet, Bootees and Shawl (31-46cm)liliac_alb20028400100% (1)

- Introduction To Accounting and BusinessDokument49 SeitenIntroduction To Accounting and BusinesswarsimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Assignment of International Business EnviormentDokument12 SeitenAn Assignment of International Business Enviorment1114831Noch keine Bewertungen

- Auditing and Assurance Services 15e TB Chapter 26Dokument24 SeitenAuditing and Assurance Services 15e TB Chapter 26sellertbsm2014Noch keine Bewertungen

- Completed ProjectsDokument3 SeitenCompleted ProjectsOrianaFernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Auditor's KPIDokument6 SeitenAuditor's KPIBukhari Muhamad ArifinNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Deposit Mobilisation of Indian Overseas Bank With Reference To Velachery BranchDokument3 SeitenA Study On Deposit Mobilisation of Indian Overseas Bank With Reference To Velachery Branchvinoth_172824100% (1)

- Table A Consolidated Income Statement, 2009-2011 (In Thousands of Dollars)Dokument30 SeitenTable A Consolidated Income Statement, 2009-2011 (In Thousands of Dollars)rooptejaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Port Aka Bin Case FinalDokument23 SeitenPort Aka Bin Case FinalRoro HassanNoch keine Bewertungen

- TBCH 12Dokument35 SeitenTBCH 12Tornike JashiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accounting Procedure Regarding Partnership Accounts On Retirement or DeathDokument108 SeitenAccounting Procedure Regarding Partnership Accounts On Retirement or Deathkarlene BorelandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short Term Decision MakingDokument4 SeitenShort Term Decision Makingrenegades king condeNoch keine Bewertungen

- FinancialquizDokument4 SeitenFinancialquizcontactalok100% (1)

- Your Electronic Ticket ReceiptDokument2 SeitenYour Electronic Ticket ReceiptEndrico Xavierees TungkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IE 001 - Case #2 - Starbucks - MacsDokument3 SeitenIE 001 - Case #2 - Starbucks - MacsGab MuyulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bus E-Ticket - 60578400Dokument2 SeitenBus E-Ticket - 60578400rsahu_36Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Cement Block Plant Study 4 LbanonDokument14 Seiten2 Cement Block Plant Study 4 Lbanonyakarim0% (1)

- Catalogue Fall Winter 2013Dokument43 SeitenCatalogue Fall Winter 2013HERRAPRONoch keine Bewertungen

- Noxon BSP Threaded FitiingsDokument24 SeitenNoxon BSP Threaded FitiingsZoran DanilovNoch keine Bewertungen

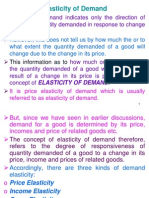

- Elasticity of DemandDokument21 SeitenElasticity of DemandPriya Kala100% (1)

- DemonetizationDokument9 SeitenDemonetizationNagabhushanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Polycarbonate Plant CostDokument3 SeitenPolycarbonate Plant CostIntratec Solutions100% (1)

- Rig Evaluation Cover SheetDokument29 SeitenRig Evaluation Cover SheetCerón Niño SantiagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hansen AISE IM Ch12Dokument66 SeitenHansen AISE IM Ch12indahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Objectives and Functions of Maintenance PDFDokument8 SeitenObjectives and Functions of Maintenance PDFAliaa El-Banna100% (1)

- Tourism Planning & Development in BangladeshDokument22 SeitenTourism Planning & Development in Bangladeshsabir2014Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 5 Ratio and ProportionDokument29 SeitenLecture 5 Ratio and Proportionsingh11_amanNoch keine Bewertungen