Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Las Minas de Falun PDF

Hochgeladen von

Jesica LengaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Las Minas de Falun PDF

Hochgeladen von

Jesica LengaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The journey of the soul towards death.

The mines of Falun, by E.T.A. Hoffmann

El viaje del alma hacia la muerte.

Las minas de Falun, de E.T.A. Hoffmann

LUIS MONTIEL

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

montiel@ucm.es

Recibido: 27-09-2013

Aceptado: 17-03-2014

Abstract

Die Bergwerke zu Falun (The Mines of Falun) is one of the most complex sto-

ries of E.T.A. Hoffmann. Starting from an event recalled in old chronicles, the writer

fantasizes on a story that shares only the ending with the documented one, which

allows for an extraordinary incursion in other depths, those of the dreams, halluci-

nations and obsessions. The whole narration demands a reading from a symbolic

perspective, where images constantly refer to what lies beyond the apparent. The

author of this paper has felt the need to put that vortex of images in parallel with the

psychology called imaginal, not without reason, by James Hillman, and that of his

master Carl Gustav Jung. From this perspective, the touchstone of the story, that is,

the death, suicidal to some extent, of the protagonist, allows for discovering values

that are not commonly accepted, not even imagined, by an Ego-centred psychology

which has generally guided the preceding interpretations of this tale.

Keywords: E.T.A. Hoffmann, The Mines of Falun, imaginal psychology, J.

Hillman, C.G. Jung.

Resumen

Die Bergwerke zu Falun (Las minas de Falun) es uno de los ms complejos

relatos de E.T.A. Hoffmann. A partir de un suceso recogido en antiguas crnicas el

Escritura e imagen 155 ISSN: 1885-5687

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_ESIM.2014.v10.46404

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

escritor fantasea una historia que slo comparte el final con la documentada, lo que

le permite realizar una extraordinaria incursin en unas profundidades diferentes a

las del subsuelo: las del sueo, la alucinacin y las obsesiones. Todo el relato exige

ser ledo en una perspectiva simblica, donde las imgenes remiten continuamente

ms all de lo aparente. El autor de este trabajo ha sentido la necesidad de poner en

paralelo ese vrtice de imgenes con la psicologa, no en vano denominada imagi-

nal, de James Hillman, y la de su maestro Carl Gustav Jung. Desde esta perspecti-

va la piedra de toque del relato, la muerte, en cierto modo suicida, del protagonis-

ta, permite descubrir valores comnmente no aceptados, ni siquiera imaginados, por

una psicologa centrada en el Yo, orientacin que por lo general ha guiado las inter-

pretaciones precedentes de la narracin.

Palabras clave: E.T.A. Hoffmann, Las minas de Falun, psicologa imaginal, J.

Hillman, C.G. Jung.

The world and the Gods are dead or alive

according to the condition of our souls.

J. Hillman. Re-imagining Psychology

Traulich und Treu ists nur in der Tiefe:

falsch und feig ist was dort oben sich freut1.

R. Wagner. Das Rheingold

1. Hoffmanns nostalgia. Soul, images and death

When, in one of his most programmatic excerpts, James Hillman, surely the

most original continuator of the thought of Carl Gustav Jung2, tries to explain what

he is going to refer to when he talks about soul, that is, when he presents the

nucleus of his psychology, he mentions among other characteristics of the former

its special relation with death and the experiencing through reflective specula-

tion, dream, image and fantasy that mode which recognizes all realities as prima-

rily symbolic or metaphorical3. Concerning the images in particular he claims, a

few lines further, to follow Jung very closely. He considered the fantasy images

() to be the primary data of the psyche. Everything we know and feel and every

1 Now only in the depths is there/tenderness and truth:/false and faint-hearted/are those who revel

above! (R. Wagner. Das Rheingold).

2 Cfr. Samuels, A. Jung and the Post-Jungians, London, Boston & Henley, Routledge and Kegan Paul,

1985. Young-Eisendrath, P.; Dawson, T. (Eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Jung, Cambridge,

Cambridge University Press.

3 Hillman, J. Re-visioning Psychology, New York-London, Harper, 1992, p. XVI.

Escritura e imagen 156

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

statement we make are all fantasy-based, that is, they derive from psychic images4.

Both distinctive notes of the soul are intensely present in the tale of Hoffmann I am

going to devote this study to; a story full of psychic images (sometimes oneiric, on

occasion hallucinatory ones) and with a deep will for death, in the sense that I

intend to explain.

Before starting the analysis of this work it is well worth placing it in the frame

of the life of his author, which will allow us to start to attach due importance to it.

I will be subject, at the moment, to the most personal aspects, leaving the historic

context for later, which might not lack interest from the adopted perspective in this

reading of Die Bergwerke zu Falun (The Mines of Falun).

Hoffmann writes the story, which he had been thinking out since February 1818,

in December of that year5, and he published it the following year in the first volume

of his vast collection of new tales, entitled Die Serapionsbrder (The Serapion

Brethren). It is, then, a maturity work Hoffmann would die four years later, aged

46, but its main singularity from my point of view is the fact that it contradicts a

melancholic confession that its author made only two years earlier, and such denial

concerns something of an enormous artistic and psychological weight.

In a letter dated on August 30th 1816, addressed to his childhood friend Theodor

Gottlieb von Hippel, he confesses with a tone of resignation, Ich schreibe keinen

Goldnen Topf mehr! (I dont write Golden Pots anymore!)6. Needless to say

that he refers to his tale of 1812 Der goldne Topf (The Golden Pot), probably his

most beloved work and undoubtedly the most magic one, a true fairy tale subtitled

ein Mrchen aus dem neuen Zeit with such an extraordinary psychological charge

that it deserved a study of nearly four hundred pages carried out by one of Jungs

closest collaborators, Aniela Jaff7. Without a doubt Hoffmann missed the joyful

fantasy that impregnates that work from beginning to end, and the hope extreme-

ly idealist in my view that its ending exudes. The passage of time had taught him

many things, among them not to trust the existence of an Atlantis of poetry, as he

envisioned in the last lines of that fairy tale8. But most likely he also missed the

4 Ibidem, p. XVII.

5 Hoffmann, E.T.A. Die Serapionsbrder, in Smtliche Werke, Bd. 4, Frankfurt am Main, Deutscher

Klassiker Verlag, 2001, p. 1323.

6 Gnzel, K. E.T.A. Hoffman. Leben und Werk in Briefen, Selbstzeugnissen und Zeitdokumenten,

Dsseldorf, Claasen Verlag, 1979, p. 320.

7 Jaff, A. Bilder und Symbole aus E.T.A. Hoffmanns Mrchen Der goldne Topf, Einsiedeln, Daimon

Verlag, 2010.

8 The main characters in the narration, Anselmus and Serpentina, join each other at the end in an ideal

world, Atlantis. The author bids farewell to them with nostalgia but archivarius Lindhorst, a sort of

deus ex machina in the story, comforts him with these words, Still still Verehrter! Klagen Sie nicht

so! Waren Sie nicht so eben selbst in Atlantis und haben Sie denn nicht auch dort wenigstens einen

artigen Maierhof als poetisches Besitztum Ihres innern Sinns? (Softly, softly, my honoured friend!

Do not lament so! Were you not even now in Atlantis; and have you not at least a pretty little copy-

157 Escritura e imagen

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

tremendous strength of the symbols and images that fill up that text. No, indeed he

had not written, and he did not count on doing it again, a story that carried inside

these many mysteries of the soul. And suddenly, a piece of news read in a work

intended for the popularization of scientific knowledge awakes that sense of

enquiry about the innermost, and the symbols, extremely powerful this time, lead

him and lead the reader to the core of the numinous.

Die Bergwerke zu Falun is one of the narrations by E. T. A. Hoffmann that can

be interpreted as a warning about the dangers that threaten the romantic way of

understanding existence, since the first impression that one gets, or rather, that one

can get when reading it, is that the death of the main character represents a punish-

ment due to the way he conceives his own existence. I do not deny that such read-

ing is legitimate, but I think I can claim that it is not the only one possible. In the

best known among his works, and probably the most widely studied, Der Sandmann

(The Sandman, 1815, published in 1817), the suicide of the protagonist and the cir-

cumstances that surround it clearly serve this purpose even though the author

guards himself well against defending the quiet life-style of the bourgeoisie.

However, in The Mines of Falun, the death of Elis Frbom, suicidal to some extent,

although this cannot be flatly stated, is surrounded by circumstances that hardly

allow for a simplifying judgement as the one mentioned above. I will briefly

remark, since I have already delved further into it somewhere else, that what seems

to be the target of his critique through the figure of Nathanael in The Sandman is

not only the romantic attitude, but more especially certain dangers hidden in the

modern technolatry that represent, precisely, the counter figure of romanticism9.

2. A news report transformed into poetic matter

The narration in question presents a non trivial peculiarity, which deserves the

special attention that somehow the author seems to recall; his starting point is a true

story, documented in a work intended for the popularization of scientific knowl-

edge. This does not represent an exception in the works of Hoffman; the novelty is

something that I have just pointed out: in this case it is the writer who states that he

has borrowed that piece of news, and he seems to do it with an explicit purpose, as

we shall soon see; but I let myself establish the hypothesis that behind this evident

purpose there is a hidden intention, maybe even for himself. Let us focus on the

explicit aspects at the moment.

hold farm there, as the poetical possession of your inward sensibility?). Hoffmann, E.T.A. Der gol-

dene Topf, in Smtliche Werke, Bd. 2/1, 1993, Frankfurt am Main, Deutscher Klassiker Verlag, p. 321.

9 Montiel, L. Sobre mquinas e instrumentos (I): el cuerpo del automata en la obra de E.T.A.

Hoffmann, Asclepio, LX- 1, (2008), pp. 151-176. Montiel, L. Sobre mquinas e instrumentos (II):

El mundo del ojo en la obra de E.T.A. Hoffmann, Asclepio, LX- 2, (2008), pp. 207-232.

Escritura e imagen 158

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

Such statement appears in a context that we could deem theoretical, conceived

as the stage of Hoffmanns poetics. I am referring to the comments that the literary

Saint Serapion Brethren provide at the end of each tale. Undoubtedly they are a

faithful representation of the style of the interventions of their flesh and bone coun-

terparts in the Serapiontic gatherings, but in the case of the present narration they

are at the service of the aesthetic principles of its author. It is beyond dispute that in

this case, as in others, Hoffmann intended to explain his way of understanding the

literary creation, but, is this the only thing to learn from his brief reference to the

source and the equally brief discussion that followed?

In the announcement that Theodor, a name that barely hides the author, makes

of the story that he is going to recount afterwards he already notes that it is ein sehr

bekanntes und schon bearbeitetes Thema von einen Bergmann zu Falun (a well-

known theme concerning a miner at Falun)10. Certainly there was something about

the story when it opened up a line of artistic reflection that had apparently been

started even before Hoffmann took it as inspiration, reaching Hugo von

Hoffmannstahl almost a century later11. It is Ottmar, pseudonym under which Julius

Eduard Hitzig12 is presented in this work, who makes a detailed mention of the

source at the end of the narration, that is, Ansichten von der Nachtseite der

Naturwissenschaft, by Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert13, one of the key works in

medicine, inspired by the Naturphilosophie by Schelling. Such mention is placed

within the framework of the debate held on each ones aesthetic proposals. This is

what Hoffmann makes his Ottmar say:

10 Hoffmann, 2001, op. cit. (note 5), p. 208. Not so elaborated but well known indeed. As I will explain

now, the anecdote on which the narration is based starts to be known in Germany as a result of some

conferences by the Naturphilosoph G. H. von Schubert in 1808 that were immediately published as a

book. A transcription of his tale appears in a literary magazine, Jason, in 1809. In 1811 Johann Peter

Hebel publishes the first, very brief, properly literary version of that story, Unverhofftes Wiedersehen.

Selbmann, R. Unverhofft kommt oft. Eine Leiche und die Folgen fr die Literaturgeschichte,

Euphorion, 94-2, (2000), pp.175-185. Sonia Santos, quoting Beck and, indirectly, Drler too, adds that

the subject is mentioned in Phbus, by Heinrich von Kleist, and constitutes the motif of a ballad by

Achim von Arnim, Des ersten Bergmanns ewige Jugend (1810), as well as the poem by Friedrich

Rckert Die goldene Hochzeit (1817). Santos, S. Anlisis mito-fenomenolgico de Die Bergwerke

zu Falun de E.T.A. Hoffmann: El complejo de Novalis, Epos, XVII, (2001), p.390.

11 After Hoffmann, other authors will use the same subject. Among them, Friedrich Hebbel, in a nar-

ration entitled Treue Liebe; Richard Wagner, in a projected opera; Georg Trakl in his poem Elis; Hugo

von Hoffmannstahl, in a drama that carries the same title as Hoffmanns tale, and Robert Musil in his

short narration Grigia. Cf. Selbmann, Ibidem, p.185.

12 Gnzel, K. Die deutschen Romantiker, Zurich, Artemis & Winkler, 1995, pp. 125-126.

13 The book includes a series of successful conferences delivered by this doctor, a disciple of

Schelling. Both these and the text had a great influence upon many romantic writers. Barkhoff, J.

Magnetische Fiktionen. Stuttgart-Weimar, J.B. Metzler Verlag, (1995), p.100.

159 Escritura e imagen

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

() aufrichtig gestanden, will mir all der Aufwand von schwedischen

Bergfrlsebesitzern, Volksfesten, gespenstischen Bergmnnern und Visionen gar nicht

recht gefallen. Die einfache Beschreibung in Schuberts Ansichten von der Nachtseite

der Naturwissenschaft, wie der Jngling in der Erzgrube zu Falun gefunden wurde, in

dem ein altes Mtterchen ihren vor fnfzig Jahren verschtteten Brutigam wieder

erkannte, hat viel tiefer auf mir gewirkt14.

In these lines we find, evidently, an opinion, an aesthetic judgement; but some-

thing else too: the simple account (die einfache Beschreibung) of the news

affected the reader much more deeply than the narration woven by Theodor. The

event per se causes a commotion, claims Ottmar, and it also affects, without a doubt,

the author of the tale; it seems to have raised in him a question, or many, which

could be summarized in this one: What might have been behind that simple story?

And in the absence of data it is not desk-based research, but fantasy, which provides

the answer to that who wonders the same question. If that answer can be the object

of interest of others is due to what we can only call the mystery of the artistic cre-

ation (no less mysterious than its success).

Simplicity versus baroque seems to be the subject of discussion in this gather-

ing; but it is not the only one, since Cyprian, possibly another heteronym of

Hoffmann, will intervene, departing from the framework of poetics to focus on an

issue pertaining to Theodors invention:

Wie oft stellten Dichter Menschen, welche auf irgend eine entsetzliche Weise unterge-

hen, als im ganzen Leben mit sich entzweit, als von unbekannten finstren Mchten

befangen dar. Dies hat Theodor auch getan, und mich wenigstens spricht dies immer

deshalb an, weil ich meine, dass es tief in der Natur begrndet ist15.

Valid or not, Cyprian claims that the treatment of the anecdote deserves credit

because the description of the main characters psychic disorder constitutes an inter-

esting matter and, much more, it is deeply rooted in nature; it is not just an easy

literary resource treated at random. For the current reader the matter is even more

complex, richer: in view of that opinion, the anecdote recalled by Schubert gains

significance for Hoffmann only from the perspective of a mood disorder; surely it

14 To speak my candid opinion, I cannot say that I care about all the Swedish Fraelse holders, the

national festivities, the spectral miners, visions, and so forth. The simple account in Schuberts Night

Side of Natural Science, of the finding of a body in the Falun Mine, which an old woman recognized

as her betrothed of fifty years before, affected me much more deeply, Hoffmann, 2001, op. cit. (note

5), pp. 239-240.

15 Writers very often show us people who perish in some disastrous way as having been at issue with

themselves all through their lives, as if under the control of unknown powers of darkness. This is what

Theodor has done; and I must say I approve of it, because I think it is deeply rooted in nature. Ibidem,

p. 240.

Escritura e imagen 160

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

is a projection in this case. Starting from the documented fact, any other of his

friends would have fantasized about it in accordance with their own personality and

from their state of mind at that moment, imagining even a different plot. However,

what matters in this case is that the simple account affects and sets in place psy-

chological mechanisms that are revealing. Even though they cannot be considered

explicative, in a scientific mode, of whatever happened or might have happened to

the unfortunate miner of Falun, they reveal something that operates in the mind of

a writer that even today keeps having legions of readers and exegetes.

I think that the translation of the news recalled by the doctor and natural

philosopher can serve my purpose; its brevity encourages me to take it as a starting

point, as Hoffmann did. Here it is:

In like manner, that remarkable corpse, the one described by Hlpher, Cronstedt, and

the Swedish scholarly journals, also decayed into a sort of ash, even after they had

placed him, to all appearances transformed into stone, under glass to keep out the influ-

ence of air. This former miner was found in the Swedish iron mines in Falun in the

course of tunnelling a connection between two shafts. The corpse, saturated in sulphuric

acid, was at first soft and supple, but then petrified through contact with the air. Fifty

years he had been lying low at the depth of three hundred meters in that acid water and

no one would have recognized the unchanged facial features of the youth who died in

the accident, no one knew the time he had passed in the shaft, since the local records

and legends concerning all accidents were unclear, if it had not been for the recognition

of his once beloved features, recollected and preserved within an old faithful love. For

as the people crowded around the salvaged corpse to gaze on his unknown still-youth-

ful physiognomy, there arrived a little old gray-haired mother, on crutches, who sank to

her knees with tears in her eyes for the beloved dead man who had been her betrothed,

and she praised the hour that had granted her, right at the portals of her own grave, such

a reunion, and the people watched with amazement as this odd couple was reunited, the

one who retained his youthful appearance even in death and down in the deep crypt, and

the other one who had preserved the youthful love inside her faded and decaying body.

The group looked on as this fifty-year silver wedding anniversary transpired between

the still youthful bridegroom stiff and cold, and the old and gray bride, so full of warm

love16.

Later we will see why it was interesting for me to transcribe this excerpt. Let us

focus now on the tale by Hoffmann.

16 Schubert, G.H. von, Ansichten von der Nachtseite der Naturwissenschaft, Dresden, Arnold, 1808,

pp. 215-216.

161 Escritura e imagen

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

3. Invitation to a journey (to the nekyia)

Who is Elis Frbom, the main character in the story? It is a young man whom

the author presents plunged into a sadness that he tries to explain to others, or

maybe to himself, as owed to the mourning over the death of his mother, which he

learnt about when disembarking from the merchant ship he enrolled in long time

ago. His shipmates insist that the he partakes in the Hnsning, the party in which

the success of their journey is being celebrated, and the way in which they try to

draw him from his dejection is revealing, since for them his sadness has a different

origin, deeper, less incidental. For the other shipmen there is something morbid

about it Bist du mal wieder ein recht trauriger Narr worden, und vertrdelst die

schne Zeit mit dummen Gedanken? (Do you want to become a true sad moony,

and waste your precious time with stupid thoughts?) 17, and something innate as

well:

Nun, nun () ich weiss es ja, du bist ein Neriker von Geburt, und die sind alle trbe

und traurig18.

Those who have lived with him during a long journey think of him, then, as a

melancholic19; what happens to him is neither accidental nor circumstantial. Only

that can explain his attitude; instead of comforting him they warn him, almost

threatening him:

Hr Elis, wenn du von unserm Hnsning wegbleibst, so blieb lieber auch ganz weg

vom Schiff! Ein ordentlicher tchtiger Seeman wird doch so aus dir niemals werden 20.

This is not the usual attitude towards someone who is mourning, but towards

that individual, out of the norm, whose behaviour generates disquiet among the nor-

mal ones. And it seems that this attitude constitutes the norm about the melancholic.

Lazsl Fldnyi, a fine scholar of melancholy, underlines the persistence of the

social rejection against the melancholic throughout the history of our culture; and

17 Hoffmann, 2001, op. cit. (note 5), p. 209.

18 All right, my hearty! () I know all about it. Youre one of these Nerika menand a gloomy and

sad lot the whole cargo of them are too. Ibidem, p. 210.

19 In fact dictionaries propose melancholic as one of the meanings of the adjective trb, which in

the quoted sentence has been translated as gloomy, precisely to avoid putting on the lips of a sailor,

or Hoffmanns hand, a word that for us can have certain value as a technical term. This is something

I will allow myself to do in my analysis.

20 Look, Elis, if you are going to stay out of our Hnsning, youd better not go back onto the ship! If

you remain like that, you wont ever be a true sailor. Hoffmann, 2001, op. cit. (note 5), p. 209.

Escritura e imagen 162

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

in a way somehow reminiscent of Foucault, he notes that the apparent tolerance of

the modern times towards the melancholic is fallacious21.

On the other hand, even though the main character tries to explain (and explain

to himself, I insist) his sadness by attributing it to his recent loss; his way of describ-

ing it clearly refutes that interpretation: im Leben gibt es keinen Menschen mehr,

mit dem ich mich freuen sollte!. (There is not a single person in my life in whose

company I can be merry any more!) 22

Note the radical terms of this negation, since, even though the sentence is enun-

ciated in the present tense, it seems to cancel the future. The world and life lack all

interest, and it gives the impression that they will remain so23. That is what the

young man transmits, what his shipmates seem to air, a morbid aroma, maybe of

death. A mate like him is unwanted on the ship deck. Elis Frbom does not see any-

thing worth living for; he is a melancholic. Even he admits that his sadness is con-

tagious. He warns the young prostitute sent by his comrades to cheer him up:

Gehnur hinein, mein gutes Kind, juble und jauchze mit den andern, wenn dues ver-

magst, aber lass den trben, traurigen Elis hier draussen allein; er wrde dir nur alle

Lust verderben24.

For long years, surely centuries, the journey, the change of scenery, was a

remedy of choice for melancholy25; and this is what someone, a certain Torbern, a

seemingly old miner, proposes for Elis Frbom; we will later know how old he is

indeed, since he has been dead for several years. A change of scenery and a change

of life style; leave the sea, he says to Elis, and go in search of the true life, which is

not other than that of a miner. And his advice goes beyond a merely therapeutic pro-

posal, since it is based precisely on the young mans personality:

Alles, was Ihr tatet, was Ihr spracht, beweist, dass Ihr ein tiefes in sich selbst gekehr-

tes, frommes, kindliches Gemt habt, und eine schnere Gabe konnte Euch der hohe

Himmel gar nicht verleihen. Aber zum Seeman habt Ihr Eure Lebetage gar nicht im

21 Fldnyi, L. Melancola, Barcelona, Galaxia Gutenberg, 2008, pp. 199-201.

22 Hoffmann, 2001, op. cit. (note 5), p. 211.

23 Without reaching such level of pessimism, the attitude that Hoffmann reflects in the quote from his

letter to Hippel somehow resembles that of his character.

24 You go back. Sing and shout like the rest of them, if you can, and let gloomy, sad Elis stay out here

by himself; he would only spoil your pleasure. Hoffmann, 2001, op.cit. (note 5), p. 211.

25 As much as the interpretation of the therapeutic efficacy of this method was explained in that time

by the theories about insanity and its possible treatment, in the Middle Ages the healing or relief of the

symptoms was attributed to the saints whose sanctuaries used to be visited on a pilgrimage, while the

medicine of the Baroque period, in its approach to iatromechanics, believed that the shaking inside the

carriages cleared away the channels for the transit of bodily fluids. Qutel, C.; Morel, P, Les fous et

leurs mdecines de la Renaissance au XXe sicle. (s.l.) Hachette, 1979, pp. 32-38 and 48.

163 Escritura e imagen

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

mindesten getaugt. Wie sollte Euch stillem, wohl gar zunm Trbsinn geneigten Neriker

(...), wie sollte Euch das wilde unstete Leben auf der See zusagen (...) Folgt meinem rat,

Elis Frbom, werdet ein Bergmann!26.

It is not, I insist, a merely therapeutic proposal, or it is so only in as far as it is

based on something even more ambitious, more decisive: the fulfilment of a des-

tiny. You are unsatisfied, seems to tell him Torbern, because you have not led your

life in the right direction, according to your innermost self. The term used by

Hoffmann in the above quotation, which I have had to translate as spirit, is the

almost untranslatable Gemt, which finds a much better correspondence with that

which I have reluctantly called the innermost of a person27. The old miner propos-

es to change the luminous surface of the sea for the darkness and depth of the mine;

from a horizontal journey to a vertical one; and this kind of journey is characteristic

of the soul28. It is much more a symbolic journey than a real one, and that is made

clear in the answer that Torbern gives to the young miner when he, almost disgust-

ed, replies to that proposal that he does not see any value in dem Maulwurf gleich

whlen und whlen nach den Erzen und Metallen, schnden Gewinns halber

(digging and tunnelling like a mole in exchange for a wretched gain)29:

Schnder Gewinn! Als ob alle grausame Qulerei auf der Oberflche der Erde, wie sie

der Handel herbeifhrt, sich edler gestalte als die Arbeit des Bergmanns, dessen

Wissenschaft, dessen unverdrossenen Fleiss die natur ihre geheimsten Schatzkammern

erschliest. Du sprichst von schnden Gewinn, Elis Frbom! ei es mchte hier wohl

noch hheres gelten (...) So mcht es wohl sein, dass in der tiefsten Teufe bei dem

schwachen Schimmer des Grubenlichts des Menschen Auge hellsehender wird, ja dass

es endlich sich mehr und mehr erkrftigend, in dem wunderbaren Gestein die

Abspiegelung dessen zu erkennen vermag, was oben ber den Wolken verborgen30.

26 All that you have said and done has shown me that you have a deeply reflexive spirit, and a char-

acter and nature pious and childish. Heaven could have given you no more precious gifts; but you were

never in all your born days in the least cut out of a sailor. How could the wild, unsettled sailors life

suit a quiet, gloomy Neriker like you? () Take my advice, Elis Frbom; be a miner. Hoffmann,

2001, op. cit. (note 5), p. 214.

27 After putting together a few quotes from German authors about the difficulty of translating this term,

and even using it adequately, Georges Gusdorf strives to clarify its meaning successfully, without

delivering an unassailable translation. Gusdorf, G. Le romantisme, vol. II, Paris, Payot, 1993, pp. 78-

80.

28 Brion, M. LAllemagne romantique. Le voyage initiatique, vol. 2, Paris, Albin Michel, 1978, p. 191.

Heraclitus (frg. 45) first brings together psyche, logos and bathun (depth): You could not find the

ends of the soul though you travelled every way, so deep is its logos () Ever after Heraclitus depth

became the direction, the quality and the dimension of the psyche. Hillman, J. The Dream and the

Underworld, New York, Harper and Row, 1979, p. 25.

29 Hoffmann, 2001, op. cit. (note 5), p. 214.

30 A wretched gain! As if all the constant wearing, petty anxieties inseparable from business up here

on the surface, were nobler than the miners work. To his skill, knowledge, and untiring industry

Escritura e imagen 164

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

Later we will find out that Torbern, when he lived, unaufhrlich Unglck

prophezeite, sobald nicht wahre Liebe zum wunderbaren Gestein und Metall den

Bergmann zur Arbeit antreibe (prophesied that some calamity would happen as

soon as the miners impulse to work ceased to be sincere love for the marvellous

metals and ores), working for financial gain31. The task of a miner claims

Torbern implies the reward of unravelling the secrets of nature, secrets presented

in the form of hidden wonders which are to be contemplated only by the one who

dares go down in search of them. And that seemingly inferior world appears to be,

according to the old miner, the reflection of the upper one, the celestial, ber den

Wolken verborgen (hidden above the clouds). Not material wealth, but knowl-

edge; and we must not forget that, for the romantics, the knowledge of the external

nature and of the innermost are nothing but two sides of the same reality, and they

represent the true objective of human existence, that one in which the progress of

the spirit becomes self-conscious.

This idea seems to give Elis enough motivation; he does not confine himself to

dismissing it melancholically; though hesitant, he sets off. And the miner, adopt-

ing ever more clearly the features of a preternatural character (at some point he

appears to Elis as a giant) will not stop guiding him; he is not a human being, then,

but a figure, an image. It is something that is not real in the purely physical sense

of the term, and that is not out of him, but comes from his inside; and that command

that comes from within, incarnated in Torbern, leads him precisely downwards and

inwards, to that great metaphor of the inside which are the bowels of the earth32.

Elis soon recognizes that same world that Torbern announces him; it is not alien to

him in any way; Und doch wer es ihm wieder, als () aller Zauber dieser Welt sei

ihm schon zur frhsten Knabenzeit in seltsamen geheimnisvollen Ahnungen aufge-

fangen (and it was something he had somehow sensed since his childhood)33.

His was, beyond appearances, an inner journey, thus labelled and described with

master hand although I may differ with some points of his interpretation by one

of the authors that I have quoted, Marcel Brion, in his Allemagne romantique; a

journey that has all the features of a nekyia, in the psychological sense that Carl

Gustav Jung gave to this Greek term34. I will try to demonstrate to what extent this

Nature lays bare her most secret treasures. You speak of gain with contempt, Elis Frbom. Well, theres

something infinitely higher in question here, perhaps () But it may be, in the deepest depths, by the

pale glimmer of the mine candle, mens eyes get to see clearer, and at length, growing stronger and

stronger, acquire the power of reading in the stones, the gems, and the minerals, the mirroring of

secrets which are hidden above the clouds. Ibidem, pp. 214-215.

31 Ibidem, p. 230.

32 Bachelard, G. La terre et les rveries du repos. Pars, Jos Corti, 1948, especially chapter VI, pp.

183-209. Brion, 1978, op. cit. (note 28), pp. 185-199.

33 Hoffmann, 2001, op. cit. (note 5), p. 216.

34 The creator of the analytic psychology translates the Greek term nekyia as Hadesfahrt, journey to

Hades, that is, the underworld in its psychic dimension. Its model is the nekyia undertaken by Ulysses

165 Escritura e imagen

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

is true, as well as the sense that the images coined by Hoffmann a sense that in all

likelihood was not totally, not even partially perhaps, perceived by himself from a

up to date psychological perspective whose roots are found in the thought of Carl

Gustav Jung.

4. The underworld and the soul

In his study The Dream and the Underworld James Hillman writes: Dreams

are the primary givens and () all daylight consciousness begins in the night and

bears its shadows35.

Well then, Hoffmann has the enormous psychological perceptiveness of initiat-

ing Eliss journey before he starts to walk. The same night of the Hnsning and the

encounter with Torbern, the young man dreams about the mine, about that mine that

in poetic and passionate tones, full of mystery and promises, has been described by

the old Torbern, whose voice he keeps hearing in his dream; it is clear that there

starts the journey of his psyche to the underworld, his nekyia. It is beyond discus-

sion that this is a purely psychical experience that lets us assume without further

digression that the mine, that foreboded mine of Falun, will end up having value for

Elis as a representation of his personal underworld. In this sense, the existence of

prophetic dreams36 should be admitted, since indeed those dreams are the expres-

sion of an unconscious urge that must be satisfied. The oneiric prophecy will be ful-

filled, because it is the expression of something experienced as fate, as an uncon-

scious objective that draws us to it with extraordinary intensity in as much as it is

felt as involuntary, as something that imposes itself upon us, and it is imposed from

outside from the dream which is enigmatically recognized as ones own37; in the

in the Odyssey. Jung, C.G. Picasso, in Smtliche Werke, Olten, Walter Verlag, 1971, Bd. 15, 154.

35 Hillman, 1979, op. cit. (note 28), p. 5.

36 I wish to emphasize again the aspect that I have introduced in the text: in this sense, i.e., in a pure-

ly psychological sense. In a couple of lines, so full of implications that his author highlights them in

italics, Jung remarks: I wished to distinguish the dreams prospective function from its compensatory

function. Jung, 8, 491. In the perspective of the history of psychoanalysis, or the deep psychology,

the importance of this statement lies in its break away from the Freudian theory of dreams; but what

matters in this context is the claim that the dream has a prospective value, not to be confused with a

prophetic one in the most common sense of the term. In the following pages Jung explains, from a

purely psychological perspective, that what he understands as the prospective character of a certain

oneiric activity is not the perception of future events but the unconscious anticipation of future con-

scious actions, a kind of previous exercise or provisional schema, a previous plan 8, 493. The expla-

nation extends up to paragraph 497.

37 The idea that the psychic, in the broad sense of the word, whilst concerning the deepest, is hardly

conceivable as ones own, internal, so it seems to come from the outside, has a long tradition in

Western thinking, including medical thought. In ancient Greece this idea was taken in an absolutely

literal sense. Cf. the first chapter of Dodds, The Greeks and the Irrational. Berkeley, University of

Escritura e imagen 166

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

case of Elis, something he had somehow sensed since his childhood. That com-

mand that comes from within has become explicit to the protagonist.

That the mine is, or may be, at the same time physical reality and psychical real-

ity, object and symbol, is something that is widely documented and elaborated by

20th century thinkers that have followed the wake of psychoanalysis. Jung himself,

Gaston Bachelard38, and more recently Hillman, have studied the poetic and psy-

chological metaphor of the depth, of the underworld, under this new light. The lat-

ter refers to the excerpt by Heraclitus quoted in a previous note. For efficacy pur-

poses I will concentrate on Hillman, in whose works the other authors thoughts

come together. This is what the American author submits regarding the underworld:

Underworld is the mythological style of describing a psychological cosmos. Put more

bluntly: underworld is psyche39.

But in mythology, and more particularly in the western one, the only culture

James Hillman asserts he refers to, not to miss his point, the underworld is populat-

ed by figures, as our psyche is; the lord of all these figures is Hades, and in Greek

religion he was considered the lord of the dead, so looking into the psyche turns out

California Press, 1992, pp.1-18, especially 13-14. More specifically in relation with the dreams see pp.

107-111 and 118-120. Galen, already in 1st Century AC, considered that one of the res non naturales,

that is, those things that do not belong to the human nature and, as a consequence, can produce dis-

eases, were the affections of the soul. None of this contradicts the fact that, also in that period,

attempts were made to associate the psychic to one or some parts of the body. Cf Onians, R. B. The

Origins of the European Thought about the Body, the Mind, the Soul, the World, Time and Fate.

Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000: to the blood, as thymos, pp. 47-49, and as animus, p.

63; to the diaphragm, as thymos, pp. 23-24, to the lungs, as animus, pp. 42-43, and to the head, as

psykhe, pp. 107-109. This same author points out that the Jewish culture gave priority to the heart in

this field, pp. 103. The efforts undertaken throughout modernity to take that original experience ad

absurdum are well known, from the postulation of the pineal gland as the site of the soul by Descartes,

up to the designation of the brain as an organ of the soul by the anatomists of the Enlightenment, a

program that reaches its peak in the current times. Cf. Hagner, M. Homo cerebralis: der Wandel vom

Seelenorgan zum Gehirn. Berlin, Berlin Verlag, 1997. This subject has been recently addressed from

the perspective of the deep psychology, both by Jung and the author whom I especially follow in my

interpretation of this story. The former points at the need (and also the difficulty) of departing from

the spatial appearance and approach the non-spatiality (Unrumlichkeit) of the soul. Jung, 6, 921.

Regarding Hillman, this is what he states: Man exists in the midst of psyche; it is not the other way

around. Therefore, soul is not confined by man, and there is much of psyche that extends beyond the

nature of man. The soul has inhuman reaches. Hillman, 1992, op. cit. (note 3), p.173. He pronounces

himself likewise in Hillman, J. The Myth of Analysis, Evanston, Northwestern University Press, 1998,

pp. 23-24, and in Hillman, 1979, op. cit. (note 28), p. 47: Underworld images are ontological state-

ments about the soul, how it exists in and for itself beyond life.

38 This author devotes a brief but suggestive analysis to Hoffmanns story. Bachelard, G. La terre et

les rveries de la volont, Paris, Jos Corti, 1948, pp. 254-260.

39 Hillman, 1979, op. cit. (note 28), p. 46.

167 Escritura e imagen

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

to be an equivalent of death. One of the excerpts quoted above has a corollary that

I removed from the quotation. Now I can fully transcribe it:

Dreams are the primary givens and () all daylight consciousness begins in the night

and bears its shadows. Our depth psychology begins with the perspective of death40.

At first, Eliss dream does not seem to offer that perspective; but when he later

arrives in Falun and leans out with curiosity to the entrance of the mine the images

of his dream will overlay those of a shipmates hallucination, a man who commit-

ted suicide shortly after describing those visions to Elis:

Als nun Elis Frbom hinab schaute in den ungeheueren Schlund, kam ihn in den Sinn

was ihm vor langer Zeit der alte Steuermann seines Schiffs erzhlt. Dem war es, als er

einmal im Fieber gelegen, pltzlich gewesen, als seien die Wellen des Meeres ver-

strmt, und unter him habe sich der unermessliche Abgrund geffnet, so dass er die

scheusslichen Untiere der Tiefe erblicke die sich zwischen tausenden von seltsamen

Muscheln, Korallenstauden, zwischem wunderlichen Gestein in hsslichen

Verschlingungen hin und her wlzten bis sie mit ausgesperrtem Rachen zum Tose

erstarrt liegen geblieben. Ein solches Gesicht, meinte der alte Seeman, bedeute den bal-

digen Tod in den Wellen, und wirklich strzte er auch bald darauf unversehens von der

Verdeck in das Meer und war rettungslos verschwunden41.

A self-fulfilled prophecy; or, as Jung would put it (see note 36), an evidence of

the prospective, not prophetic, condition of some dreams. In any case the associa-

tion made by Elis has just brought death to the foreground and his reaction is fright:

Daran dachte Elis, denn wohl bednkte ihm der Abgrund wie der Boden der von den

Wellen verlassenen See, und das schwarze Gestein, die blaulichen, roten Schlacken des

Erzes schienen ihm abscheuliche Untiere, die ihre hsslichen Polypen-Arme nach ihm

ausstreckten42.

40 Ibidem, p. 5.

41 As Elis Frbom looked down into this deep abyss, he remembered what the old steersman of his

ship had told him once. At a time when he was down with fever, he thought the sea had suddenly split

apart, and the boundless depths of the abyss opened under him, so that he saw all the horrible crea-

tures of the deep twining and writhing about in dreadful and vengeful contortions among thousands of

extraordinary shells and groves of coral, till they stood still in a death-like immobility. The old sailor

said that to see such a vision meant death, ere long, in the waves; and in fact very soon he threw him-

self overboard, unnoticed, and it was impossible to rescue him. Hoffmann, 2001, op. cit. (note 5), p.

220-221.

42 Elis thought of that: for indeed the abyss seemed to him to be a good deal like the bottom of the

sea run dry; and the black rocks, and the blue and red slag and scoria, were like horrible monsters

shooting out polyp-arms at him. Ibidem, p. 221.

Escritura e imagen 168

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

But even though the death of the pilot cannot stop relating to the end of life, in

our domain, I insist, it must be seen in its symbolic context. The underworld, of

which the mine is a reminder or an announcement, the realm of Hades, is a place

where time as we experience it when alive does not exist, but that does not mean

claims Hillman that it is beyond time or after life:

The House of Hades is a psychological realm now, not an eschatological realm later43.

This does not imply that it lacks any dangers; if the existence of the body is not

at risk, the soul will be. The most experienced miners know it and warn him since

the beginning of their relationship:

Es ist ein alter Glaube bei uns, dass die mchtigen Elemente, in denen der Bergmann

khn waltet, ihn vernichten, strengt er nicht sein ganzes Wesen an, die Herrschaft ber

sie zu behaupten, gibt es noch andern Gedanken Raum, die die Kraft schwchen, wel-

che er ungeteilt der Arbeit in Erd und Feuer zuwenden soll44.

They are not referring here to something as physical as a collapse, a flood the

water is not even mentioned or an explosion. They are talking about the struggle

against the elements, and more concretely against two of them, the earth and the

fire. The water and the air dominated his old life as a sailor, and in no way they were

as threatening to his eyes:

O Herr meines Lebens, was sind alle Schauer des Meeres gegen das Entsetzen was dort

in dem den Steingeklft wohnt! Mag der Sturm toben, mgen die schwarzen Wolken

hinabtauchen in die brausenden Wellen, bald siegt doch wieder die schne herrliche

Sonne und vor ihrem freundlichen Antlitz verstummt das wilde Getse, aber nie dringt

ihr Blick in jene schwarze Hhlen, und kein frischer Frhlingshauch erquickt dort unten

jemals die Brust45.

This is true. But, maybe just because it is so, the pilot wanted to go in search of

the abyss that the wet elements did not offer him46. By this we start to have a dif-

43 Hillman, 1979, op. cit. (note 28), p. 30.

44 It is an old belief with us that the mighty elements with which the miner has to struggle destroy

him unless he strains all his being to keep command of them if he gives place to other thoughts which

weaken that vigour which he has to reserve wholly for his constant work among Earth and Fire.

Hoffmann, 2001, op. cit. (note 5), p. 225.

45 Lord of my Life! What are the dangers of the sea compared with the horror which dwells in that

empty abyss of rock? The storm may rage, the black clouds may come whirling down upon the break-

ing waves, but the beautiful, glorious sun soon gets the mastery again and the storm is past. But never

does the sun penetrate into these black, gloomy caverns; never a freshening breeze of spring can revive

the heart down there. Ibidem, p. 221.

46 In the theory of elements, which reaches its most widely accepted expression, at least in medicine,

169 Escritura e imagen

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

ferent point of view regarding what the meaning of death might be, which will be

useful to us when estimating the sense that Elis Frboms death has. But, for every-

thing to be sufficiently proven, we must try hard to find more symbolic keys in the

Hoffmannian text.

5. Searching for the Queen

In his dream the young man contemplates, as a promise, never seen gemstones,

and he senses the presence of a tremendous hidden power in the deepest, which

Torbern names the Queen: a female power that drags him down to the depth while

other female figures pull him out from the opposite direction: the mother, whose

voice he hears, calling him from the surface; his girlfriend to be, whose image he

contemplates, extending her hand to him, when, following her voice, he looks up.

In his dream, Torbern adopts an ambiguous attitude: on the one hand, he prevents

Elis from the danger, but, on the other hand not in vain is he the messenger of the

deep he warns him, sei treu der Knigin (Be faithful to the Queen) 47.

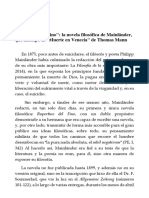

Who is this mysterious Queen? Is she, maybe, a figure invented by the fantasiz-

er Hoffmann? Not indeed; all the opposite, she is a figure well known by the min-

ers from ancient times, and of course by the writers contemporaries. In a German

mining treaty published in 179448 that is, when Hoffmann was 18 years old the

Queen appears on the cover drawing:

in the model proposed by Empedocles, the inherent qualities of the water element are coldness and

humidity, and those of the air are humidity and warmth. The earth, in contrast, is cold and dry, and the

fire is hot and dry. And this adds a particularly relevant piece of information to our reading: another

pre-Socratic physiologoi, Heraclitus, claimed that for the soul it is death to turn into water. Thus

there would be, according to that ancient wisdom, certain death threats which Eliss new mates seem

to be afraid of- that are not to be feared by the soul. Regarding the symbolism of elements, besides

Bachelards classic studies, some of which are quoted in this paper, the following can be consulted:

Bhme, G. and H, Fuego, agua, tierra, aire. Una historia cultural de los elementos, Barcelona,

Herder, 1998. In relation to the narration in hand, Santos, 2001, op. cit. (note 10).

47 Hoffmann, 2001, op. cit. (note 5), p. 217.

48 Winckler, C.J. Praktische Beobachtungen ber den Betrieb des Grubenbaues auf Fltzgebirgen,

besonders der Kupferschiefern zur Unterrichte des Bergwerks-Eleven zu Rothenbug bestimmt. Berlin,

Himburg, 1794.

Escritura e imagen 170

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

The figure is readily identifiable: a crown with the shape of a fortress surrounds

her forehead; some keys in her hand and two lions at her feet: Hippomenes and

Atalanta transformed into such beasts, which in other images appear yoked to her

chariot; it is, of course, Cybele, the Mother of the Gods or Mountain Mother,

lady of not only the surface of the mountains, but also, and more than anything, of

what they keep inside, and for that reason she is the sacred queen of mining. The

keys are, without a doubt, those which allow access to Hadess underworld. Not for

nothing there is a continuum, which often leads to identification, between the fig-

ure of this Phrygian goddess (Rhea-Cybele) with his daughter Demeter and with the

latters daughter, Persephone, wife of Hades49. And it should not be overlooked that

in the myth Demeter looks for her daughter, kidnapped by the lord of the under-

world as though she were the lost half of herself and found her at last in the

underworld50.

But we not only know this: Cybele is also one of the deities to whom the antique

Greek entrusted the people suffering from what we would call mental illnesses51.

This figure, comprehensive of all the aspects of the feminine must necessarily

be ambiguous, for it implies both the most luminous and the darkest; it is the anima

that inhabits the deepest, where it rubs elbows with the shadow (der Schatten), or

even more, it blends until being confused with one another. It includes within itself,

as could not be otherwise, love and death. I believe that its message is this: there is

no love where death is denied; that who wishes love has to assume the death. But

in this assumption lies the seed of certain transcendence, a domain beyond the com-

mon death (not to forget that I am talking in terms relative to the psychical life), as

we will see later.

For the moment we have already discovered in the depth of the mine or

rather, in the underworld of dream three images of the feminine: the mother, the

49 Kernyi, K. Eleusis. Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter, Princeton, Princeton University

Press, 1991, p.132.

50 Ibidem, p. 130.

51 Dodds, 1992, op. cit. (note 37), p. 77. There is another item that surely is not trivial. According to

this author the worship of Cybele reaches its acme in Athens in the context of a severe cultural and

social crisis: the war against Sparta and the plague, catastrophes that occurred in the time in which a

great rationalist culture unleashed under the government of Pericles (pp. 193-194). Maybe it is not a

coincidence that the modern sacrifice of Attis, the young man in love with Cybele, imagined by

Hoffmann, concurs with the breaking of the patriotic and democratizing ideals of the German youth

through the repression triggered by the Carlsbad Decrees (1819.) Cfr. Montiel, L. Daemoniaca.

Curacin mgica, posesin y profeca en el marco del magnetismo animal romntico, Barcelona,

MRA, 2006, pp. 91-94. In the case of the writer, his member status in the supreme court

(Kammergerichtsrat) will provoke even more tension, since in 1819 he will be requested to draft files

against the so-called demagogues, with whom he sympathizes. Hoffmanns rebellious attitude

would cause him serious complications from which only his early death freed him. Cfr. Gnzel, 1979,

op. cit. (note 6), pp. 5-6, 373-406 and 433-474.

171 Escritura e imagen

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

girlfriend and the Queen; the first two being protective, while all three are posses-

sive, each in their own way. Two of them offer the security of life in the outside,

while the other exhibits the dangerous riches that hide in the depth. But there is also

Torbern, the messenger of the depths, the mystagogue, he who teaches the neophyte

what he would have never imagined on his own (by his own I mean his conscious

self); a messenger appearing in the midst of sadness. That sadness is conditioned by

a loss that is however revealed to us as the emergence of something much more rad-

ical, the melancholic mood, a predisposition to listen to the messages of an equally

sombre herald. The miners know the legendary figure of a remote partner

endowed with that character that had the rare ability to find wonderful veins and

who would have died trapped, or disappeared in the mine, decades before, appear-

ing once in a while to address them with an admonitory tone, demanding loyalty to

the queen. And this legendary character also mentions a certain Prince of metals.

Hades himself, perhaps? Once more it is Hillman who reminds us, or lets us know,

that the Greek Hades was hardly ever referred to by his name, but with euphemisms

such as the unseen or Trophonius, which means the nutritor, and who joined the

Roman pantheon as Ploutos, i.e., the owner or/and provider of riches, often repre-

sented pouring out the content of a cornucopia. Did those Greeks and Romans sus-

pect that Hades was () the giver of nourishment to the soul52?

In any case, many characters move within that underworld, which coincides

with Hillmans thesis that Greek polytheism translated the original psychological

experience that the supposed unity of the self rests upon an iridescent and ambigu-

ous multiplicity, each of whose elements is, in the end, sacred. I have already

remarked how the feminine figures, the queen at the head, represent, from this per-

spective, what Jung called anima, the image of the feminine inserted in the psyche

of all human being; in the same way, Torbern bears an extraordinary resemblance

with the archetypal figure referred to as shadow, der Schatten. But Hillman has

gone even further; for him, the anima represents the soul as such, in its totality

(while not in its unity; we have already seen that its essence is multiple), and the

shadow is also a part of the soul53:

52 Hillman, 1979, op. cit. (note 28), p. 28.

53 By soul I mean () a perspective rather than a substance, a viewpoint toward things rather than a

thing itself. This perspective is reflective; it mediates events and makes differences between ourselves

and everything what happens. Between us and events () [The soul] makes meaning possible, turn

events into experiences, is communicated in love and has a religious concern () By soul I mean

the imaginative possibility in our natures, the experiencing through reflective speculation, dream,

image and fantasy that mode which recognizes all realities as primarily symbolic or metaphorical.

Hillman, 1992, op. cit. (note 3), p. XVI. In the same page he claims to use the term soul as inter-

changeably with psyche (from Greek) and anima (from Latin).

Escritura e imagen 172

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

Shadow is the very stuff of the soul, the interior darkness that pulls downward out of

life and keep one in relentless connection with the underworld54.

Is not this what Torbern does, what he intends to do with the other miners? And

is he not indeed at the service of the Queen, as if he simply was a part of hers? The

story that Hoffmann has started to narrate strongly resembles the account of the US

psychologist. The mine happens to be an excellent metaphor. Among the character-

istics that Hillman attributes to our representations of the psychic underworld stands

out the very specific way of referring to the space; apart from being underlying it

is always limited:

The fundamental image of all underworld is that of the contained space () whether

this be the consulting room itself, the close therapeutic relationship, the hermetic vessel

in which the work is done, the dream-journal or the going inward in imagination. All

these derive from the deep and closeted underworld. We may experience the dream

topos as () an incubation, a labyrinth, pregnancy, or claustrophobic catacomb () So

we talk of going in to analysis or of finding no way out of analysis, for the depths

of psychotherapy have become one of the places today of experiencing psychic

space55.

We know how Eliss adventure finishes. The day of his wedding with Ulla, the

daughter of the mines owner, Elis, with a crumpled face, announces to the bride-

to-be that he needs to enter the mine, and he does it with this argument:

Ich will dir nur sagen, meine herzgeliebte Ulla, dass wir dicht an der Spitze des hchs-

ten Glcks stehen, wie es nur den Menschen hier auf Erden beschieden. Mir ist in die-

ser nacht alles entdeckt worden. Unten in der Teufe liegt in Chlorit und Glimmer einge-

schlossen der kirschrot funkelnde Almandin, auf den unsere Lebenstafel eingegraben,

den musst du von mir empfangen als Hochzeits-Gabe. Er is schner als der herrlichste

blutrote Karfunkel, und wenn wir in treuer Liebe verbunden hineinblicken in sein strah-

lendes Licht, knnen wir es deutlich erschauen, wie unser Inneres verwachsen ist mit

dem wunderbaren Gezweige das aus dem Herzen der Knigin im Mittelpunkt der Erde

emporkeimt56.

54 Hillman, 1979, op. cit. (note 28), p. 56.

55 Ibidem, p.189.

56 I only want to tell you, my beloved Ulla, that we are just arrived at the verge of the highest good

fortune which it is possible for mortals to attain. Everything has been revealed to me in the night which

is just over. Down in the depths below, hidden in the chlorite and mica, lies the cherry-coloured

sparkling almandine, on which the tablet of our lives is graven. I have to give it to you as a wedding

present. It is more splendid than the most glorious blood-red carbuncle, and if, united in truest affec-

tion, we look into its streaming splendour together, we shall see how the branches that shoot from the

Queens heart, from the central point of the Earth, grow in our hearts. Hoffmann, 2001, op. cit. (note

5), pp. 236-237.

173 Escritura e imagen

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

Perhaps it is not a mere coincidence that Hoffmann chooses to put an end to the

purely physical death of the young miner the day of Saint John, the author of

Apocalypse, a term which, as we know, is translated as revelation57

6. An animic view of suicide

As I hastened to add at the beginning of the article, most surely the thorniest

problem that this tale poses lies at the axiological level. How to interpret the writers

decision of having a suicidal character as the protagonist of the story? Why inter-

preting as a suicide the death, by an unknown cause, of the historic miner of Falun?

As I observed before, there exists a certain resemblance between the character in

The Mines of Falun and the Nathanael from The Sandman, which denotes the

authors evident concern about the value of an existential option of both characters

that seems to have so many points in common with the deepest, the romantic per-

sonality of their creator. I think it is easy to accept the most immediate interpreta-

tion, which suggests the deep conviction that the radical choice of the values

deemed as romantic is hardly compatible with a socially accepted existence and can

lead that who fulfils it to situations incompatible with life. But Hoffmanns insis-

tence seems to indicate that just turning our backs to this choice is not the best

resource. The problem to solve could be formulated like this: denying life, or deny-

ing an authentic and fulfilling existence? However, this would not be a problem, but

a dilemma. To transform it into a problem it is necessary to consider that a third

option may exist, a way to a solution that is not formulated in negative terms. Does

that third way exist?

In the preceding pages I have started to outline an answer that aims at distin-

guishing the psychological and symbolic from the biological and material. But I

will not fall into the crude idealism of supposing that both dimensions can be sep-

arated. Things are not, and cannot be, so simple, since both fields are interpenetrat-

ed in an indissoluble manner in the human being. What I postulate is that a look

a deep look may help navigate among these sandbanks. And we have the fortune of

counting on an expert pilot.

James Hillman has studied the pressing problem of suicide from a new psycho-

logical perspective. Not leaving aside the material fact, be it the destruction of ones

own life or the attempt to achieve such thing, he has proposed an interpretation of

the deepest sense of the urge for death; an interpretation that, even if it leads to cer-

57 This is not the only possible explanation. Sonia Santos points out that the text mentions Saint Johns

day in 1687 as the date of death of the real Torbern, caused by the collapse of the mine, and remarks

E.T.A. Hoffmanns personal taste for the solstice season of the year (...) and its mythical, primitive

and magic significance. Santos, 2001, op. cit. (note 10), p. 399.

Escritura e imagen 174

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

tain value judgments, does not derive from an axiological consideration58. I will try

to summarize it with the purpose of putting it to test in parallel with the literary

example created by Hoffmann.

The provocative novelty of such interpretation is the point of view adopted.

First, the recognition of something obvious which, nonetheless, tends to be forgot-

ten, surely in a movement of self-defense:

Suicide is one of the human possibilities. Death can be chosen59.

Once this is acknowledged death does not appear anymore as mere negativity,

but as the result of a personal choice whose motives have to be discovered. To that

end, it is indispensable to abandon the common point of view, which certainly is at

the service of life, but and this is essential- life considered from the merely bio-

logical point of view. Here we could not even deal with psychology, but with the

human mode of that self-preservation instinct observed in the entire nature. Which

must be, then, the new point of view? Hillman makes it clear in his introduction to

the first edition of his book about the subject:

This little book () approaches the suicide problem not from the viewpoints of life,

society and mental health, but in relation to death and the soul. It regards suicide not

only at an exit from life but also as an entrance to death60.

In relation to death and the soul. The first thing to wonder is what kind of rela-

tionship there is, in his opinion, between soul and death which can justify the use

of the copulative conjunction in the quoted text. This association had been estab-

lished by Jung, but Hillman is going to deepen into it in a more detailed manner.

According to both authors, the psychic adventure that unfolds, well or wrong,

throughout our entire life, which Jung called individuation process, does not end

until our biologic existence finishes, hence death is end in a double sense: at the

same time finis and telos61, conclusion and goal62. But, as it happens with the bio-

logic life, the psychic life can, and even needs to, experience several deaths:

58 The issue is not for or against suicide, but what it means in the psyche. Hillman, J. Suicide and

the Soul, Putnam, Spring Publications, 1997, p. 37.

59 Ibidem, p. 41.

60 Ibidem, p.11.

61 Hillman, 1979, op. cit. (note 28), p.30.

62 Aniela Jaff, in her book about the Golden Pot claims that for Jung the psychological path of indi-

viduation is ultimately a preparation to death. Cit. in Hillman, 1979, op. cit. (note 28), p. 89. In that

same work Hillman himself subscribes that point of view: If we stare these questions in the face, of

course we know where our individuation process is going to death (p. 31).

175 Escritura e imagen

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

Approaching death requires a dying in soul, daily, as the body dies in tissue. And as the

bodys tissue is renewed, so is the soul regenerated through death experiences63.

The health of the soul demands death; the definitive one, as a true perspective64;

and an indeterminate series of what we could call partial deaths, or psychic death

experiences, as the only means for the change, for the development, for that called

rebirth in the frame of Jungian psychology; the individuation process is and cannot

stop being a series of deaths and rebirths in the psychic sphere. Our conscious ego

can only conceive death as an annihilation of its physical life, but the death that is

interesting for the soul is of a different kind; it is a death that has to do with that

kind of immortality, the only one that the human being can experience, which man-

ifests itself in the rebirth. Death is the most profoundly radical way of expressing

this shift in consciousness65.

In this perspective the thanatotic experience loses a great part, if not all its neg-

ativity. Suicidal ideas, even suicide attempts not carried out, could be the result of

this desire for change, for deepening, of the soul, which is difficult to express oth-

erwise. At this point it is necessary to remark that, with regard to the main charac-

ter in the story, while his death is suicidal to a great extent he faces a dangerous

situation and he finally loses his life- in his case it is not an active suicide, as in the

case of his predecessor, the Nathanael from Der Sandmann, who plunges from the

top of a tower. This assertion from Hillman can be applied to him:

The impulse to death need not be conceived as an anti-life movement; it may be a

demand for an encounter with absolute reality, a demand for a fuller life through the

death experience66.

I believe that there is not a great distance between Eliss attitude and that of

many of our contemporaries who practice high-risk sports, although the question is

to find out how many among these perceive that, beyond money and fame, they may

be looking for the Queen in that fuller life. The issue is that, even when death, or

more precisely, the experience of death, as Hillman himself remarks, may entail a

real danger for survival, it has or can have a positive psychological value, even a

very high value:

63 Hillman, 1997, op. cit. (note 58), p. 61.

64 Death is the only absolute in life, the only surety and truth () Life and death are contained with-

in each other, complete each other, are understandable only in terms of each other. Life takes on its

value through death, and the pursuit of death is the kind of life philosophers have often recommend-

ed. If only the living can die, only the dying are really alive. Ibidem, p. 59.

65 Hillman, 1979, op. cit. (note 28), p. 66.

66 Hillman, 1997, op. cit. (note 58), p. 63.

Escritura e imagen 176

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

The death experience is needed to separate from the collective flow of life and to dis-

cover individuality () Then suicide is the urge for hasty transformation67.

In that perspective we are not authorized to interpret Hoffmanns narration from

the value table of life, understanding this from both the merely biological stand-

point and also the perspective of the socially accepted; and in that social acceptance

I include the psychological perspective based in the self, counting the most classic

viewpoint of psychoanalysis, as Hillman does in his theoretical discourse. For him,

the descent into the underworld, understood as a heroic fantasy, as a challenge for

an ego that has to re-emerge victor, is a psychological error68. It goes without say-

ing that such argument, whilst longstanding in literature69, represents the antithesis

of the narrated in Die Bergwerke zu Falun. That heroic fantasy, he adds, acts

against the freedom of the soul70. Well then, Hoffmann had sufficient talent

genius? to accept that freedom against the conventions of his time, and of ours.

Yes; also our time, since more than a few, and not the worst, have interpreted

Elis Frboms and his creators choice differently, negatively. For reasons of space

I shall only mention some of the most relevant instances. Marcel Brion, whom I

greatly admire, starts his interpretation in a way that closely approximates to mine,

by referring to the metaphor of the opus magnum of the alchemists, so precious to

Jung, but then he most unexpectedly affirms:

Hoffmanns tale, on the contrary, makes a petrifaction if it, and even if the half century

spent in that substance that gives to death the appearance of life and youth brings the

fifty year disappeared Frbom back to light, this resurrection presents a repulsive

aspect71.

As for Rdiger Safranski, he compares the end of the tale with the confinement

inside the crystal of the student Anselmus from Der goldne Topf, a confinement

from which in that story he will be finally freed by his love for Serpentina:

But also his fall [Eliss] ends up in the crystal72 () here too the immersion in the

wonderful, which breaks the bridges with reality, leads to a glass jail. That is the les-

son of the story73.

67 Ibidem, p. 64 and 73.

68 Hillman, 1992, op. cit. (note 3), p. 39.

69 Hillman gives as an example the violent burst of Hercules into the kingdom of Hades. Hillman,

1992, op. cit. (note 3), p.38. Hillman, 1979, op. cit. (note 28), pp.110-117.

70 Hillman, 1992, op. cit. (note 3), p.39.

71 Bachelard, 1948, op. cit. (note 32), p.186. He also deems the beauties of which the garnet is a sym-

bolas chimeric, and Eliss imagination as foolish (p.190).

72 Ins Kristall bald dein Fall! Youll soon end up in the crystal!-, the old ladys curse of

Anselmus.

73 Safranski, R. E.T.A. Hoffmann. Das Leben eines skeptischen Phantasten. Mnchen & Wien, Hanser,

1984, p. 322.

177 Escritura e imagen

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

The lesson? With all the respect that I have for Safranksi, which is high, I think

that in this case it would be better to say the moral; but I think that nothing is far-

ther away from the depth of these mines than a moral. It is my honest belief that

only from a line of thought as the one I have chosen to guide my interpretation can

justice be made to such masterpiece. On the other hand, there are some arguments

which, in close synthesis, I will explain to conclude.

Apart from Eliss suicidal attitude, the great argument that is usually raised to

claim his insanity and the negativity of his attitude and along with them,

Hoffmanns supposed criticism to the romantic choice of a fantastic world

instead of a real one is his election of the Queen over his real beloved, since we

should not forget that Elis truly loves Ulla. But let us not forget either the argument

the young man presents to his fiance when he decides to go down in search of the

garnet: without it they will never get to be really united. In his book on melancholy

Fldnyi offers us a key that can shed some light on this episode. The one who is

in love, claims the Hungarian philosopher, does not seek marriage or children,

since his intentions go beyond; go to the world of imagination, of illusion, and ulti-

mately, of nothingness; and, as an example of his thesis an example that is most

appropriate in the case of Elis and Ulla- he quotes this text of Hlderlin: The love

dies as soon as the gods run away74.

7. By their fruits you shall know them

On the other hand, the death of the young man and the late discovery of his pet-

rified corpse present a symbolism that cannot be overlooked. When, fifty years

later, he is unearthed, what scene might the bystanders have contemplated?

Schubert I promised I would return to his text- describes it with master hand:

The group looked on as this fifty-year silver wedding anniversary transpired between

the still youthful bridegroom stiff and cold, and the old and gray bride, so full of warm

love75.

The bride has aged, but the groom has remained preserved from decadence.

Only when he is touched by the air of the outside world he disappears definitively,

turned to dust. Bachelard, who cannot avoid the common negative assessment of

this ending, has a hint of Hoffmanns true intention though:

74 Fldnyi 2008, op. cit. (nota 21) p. 261. Following this quote Fldnyi writes: The lover would

like to merge the absolute abstraction and the flesh and blood individuality. That is why his destiny is

always tragic.

75 See note 16.

Escritura e imagen 178

Vol. 10 (2014): 155-179

Luis Montiel The journey of the soul towards death...

As soon as it is taken out of the mine, the mineralized body pulverizes itself, as if it were

forbidding any positive research about the wonderful occurrence, as if the author sud-

denly gave up on all the dreams of mineralization76.