Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Golden Arrow (Car)

Hochgeladen von

HeikkiCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Golden Arrow (Car)

Hochgeladen von

HeikkiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Golden Arrow (car)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Golden Arrow was a land speed record racer built in Britain

to regain the world land speed record from USA. Henry Golden Arrow

Segrave drove the car at Daytona Beach and exceeded the

previous record by 24 mph or 39 km/h.

Contents

1 The car

1.1 Irving

1.2 Backers

1.3 Suppliers

2 References

3 External links The Irving-Napier Golden Arrow

at the National Motor Museum, Beaulieu

Overview

The car Production one-off (1928)

Built for ex-Sunbeam racing driver Major Henry Segrave to Designer John Samuel Irving (1880-1953)

take the Land Speed Record from Ray Keech, Golden Arrow Body and chassis

was one of the first streamlined land speed racers, with a Body style front-engined land speed record car.

pointed nose and tight cowling. Power was provided by a

Powertrain

23.9 litre (1462 ci) W12 Napier Lion VIIA aeroengine,[1]

specially prepared by Napiers, designed for the Supermarine Engine 925 hp, 23.9 litre naturally aspirated

aircraft competing in the Schneider Trophy, producing 925 Napier Lion W12 aero engine,

hp (690 kW) at 3300 rpm.[2] ice cooling, no radiator

Transmission 3-speed, final drive through twin

The car was designed by ex-Sunbeam engineer, aero-engine

driveshafts running either side of

designer and racing manager Captain John Samuel Irving

driver

(1880-1953).[3] It featured ice chests in the sides through

which coolant ran and a telescopic sight on the cowl to help

avoid running diagonally. The Rootes brothers, friends of Segrave and Irving, provided the Irving-designed

individual aluminium body panels from Thrupp and Maberly.[1]

In March 1929, Segrave went to Daytona, and after a sole practice run,

on 11 March, in front of 120,000 spectators,[2] set a new flying mile at

231.45 mph (372.46 km/h), easily beating Keech's old speed of

207.55 mph (334.00 km/h). Two days later, Lee Bible's White Triplex

crashed and killed a photographer.

Daytona Beach was closed and Segrave was unable to make further runs

to achieve the planned higher speeds.

The Golden Arrow in 1929.

Segrave was killed attempting a water speed record the next year.

Golden Arrow never ran again.

Irving

Contemporary reports refer to the car as the Irving-Napier Golden Arrow.[4]

He had left Sunbeam and Irving's new employers, Humfrey-Sandberg, granted him permission to use part of his

time designing and constructing Golden Arrow for ex-Sunbeam driver Henry Segrave. Golden Arrow was,

Segrave said, very docile compared with other cars of its kind.[5] After the first trial run when he established no

goggles were necessary at 182 mph Segrave drove the car up some planks to get it off the beach then drove it

back along the main street of Daytona to its garage.[5]

The sponsors required a British brand name for the engine and Napier

was chosen. Dunlop's tyres were not warranted safe beyond 250 mph so

the planned maximum of 274 mph was pulled back. To minimise frontal

area Irving based the shape of the nose on the racing Supermarine S.5's

cowling. Leading fairings in front of the front wheels gave no useful

improvement and they were abandoned. An irreducible minimum was

arrived at for the size of the cockpit because it had to be large enough

for a sixteen-inch steering wheel believed to be needed to give sufficient

leverage. In the end a large tail fin was adopted in case of side gusts, it

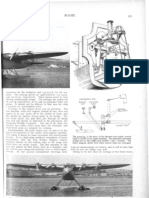

A Napier Lion II engine cutaway

located the centre of gravity an inch in front of the centre of pressure.

The whole shell was shaped to exert a downward air pressure to keep

the driving wheels on the ground and assist stability but a further

260 lbs of lead ballast was added to the tail. The twin prop-shafts were

given strong casings in case they came apart at high speed. The axle

was given no differential. At that time the car was notable among land

speed record cars for having 4-wheel brakes. Suspension was by half-

elliptic leaf springs all round, axle travel was limited to just 1 inches

in front and 1 at the rear axle. The car was built at KLG Works on

Kingston Hill.[5]

Engine fairings removed

Segrave found he could not use all the throttle opening until past 2400

rpm, or, in bottom gear, until the car was moving in excess of 55 mph.

The engine ran throughout without a misfire and the extra ice cube calling turned out to be unnecessary.

Segrave made just the two runs. Including that first test run it is doubtful if the car has travelled as much as 40

miles in its whole life.[5]

Irving was helped by chief draughtsman W U Snell, his brother lent by Alvis to supervise the car's building and

his daughter who dealt with all the associated progress-chasing and administrative work.[5]

The engine cannot be run again because the cylinder blocks were not properly inhibited and are now too

porous. Wakefield / Castrol presented the car to the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu in 1958.[5]

Backers

Sir Charles Wakefield (Castrol)[6]

O J S Piper, Portland (Red Triangle) Cement (Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers)[4][5]

H O D Segrave (the driver)[6]

Suppliers

Engine - Napier & Son, Acton

Body - Thrupp & Maberly, Rootes brothers

Assembly - Robinhood Engineering Works, Newlands, Putney Vale

Spark plugs - KLG

Steering - Marles

Chassis frame - John Thompson (Wolverhampton)

Shock absorbers - T B Andre, London

Ball bearings - Ransome & Marles

Cardan shafts - Hardy Spicer

Gearbox - Gillett Stephen and Co, Bookham

Brake operation - Clayton Dewandre, Lincoln

Radiators - Gloucester Aircraft

Special steels - Vickers Armstrong

Fuel - British Petroleum

Oil - C. C. Wakefield & Co[6]

References

"Golden Arrow, between earlier and later land speed record cars at Beaulieu". twopsgoss. External link in

|publisher= (help)[7]

1. "Golden Arrow". World of Automobiles. Volume 7. London: Orbis Publishing Ltd. 1974. p. 799.

2. Tom Northey. (1974). "Land Speed Record".World Of Automobiles. Volume 10. London: Orbis Publishing Ltd.

pp. 116166.

3. Captain J. S. Irving.The Times, Tuesday, Mar 31, 1953; pg. 8; Issue 52584.

4. Interview: Captain J. S. Irving, designer of the Irving-Napier Special.

Motor Sport, page 7 May 1929

5. The inside story of the Irving-NapierGolden Arrow. Motor Sport, page 56 July 1981

6. John Bullock, The Rootes Brothers, Patrick Stephens, Sparkford SomersetISBN 1852604549

7. "National Motor Museum collection"(https://web.archive.org/web/20110305105211/http://www.beaulieu.co.uk:80/beau

lieu/motorcollection). National Motor Museum. Archived fromthe original (http://www.beaulieu.co.uk/beaulieu/motorc

ollection) on 5 March 2011.

External links

"Fastest Thing On Wheels", June 1929, Popular Science

Wikimedia Commons has

Eric Dymock, Robert Horne's Golden Dream, Extracted from media related to Golden

Sunday Times Supplement May 1990 Arrow (land speed racer).

National Motor Museum website

Retrieved from "https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Golden_Arrow_(car)&oldid=785178149"

Categories: Vehicles powered by Napier Lion engines Wheel-driven land speed record cars

Automobiles powered by aircraft engines

This page was last edited on 12 June 2017, at 02:36.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may

apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia is a registered

trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Napier RaitonDokument4 SeitenNapier RaitonZupp ZappNoch keine Bewertungen

- Z Drive TechnologyDokument16 SeitenZ Drive Technologyebey_endun100% (1)

- Land Speed Record Norman SuperchargersDokument5 SeitenLand Speed Record Norman Superchargersandrew_harveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Screw Propelled VehicleDokument4 SeitenScrew Propelled Vehiclejpalex1986Noch keine Bewertungen

- WankelDokument24 SeitenWankelKunchala SaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phil Irving - Web PDFDokument3 SeitenPhil Irving - Web PDFprakash saralayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- WankelDokument24 SeitenWankelSonu YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sidecar of BicycleDokument20 SeitenSidecar of BicyclePankaj KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wankel EngineDokument20 SeitenWankel EngineDennis Dale100% (1)

- Design of Radial Engine With Different Metals Using AnsysDokument74 SeitenDesign of Radial Engine With Different Metals Using Ansysibrahim67% (3)

- Royal Enfield's Branding Strategies Through the YearsDokument56 SeitenRoyal Enfield's Branding Strategies Through the Yearsshail5554100% (4)

- 100 Years Aircraft EngineDokument11 Seiten100 Years Aircraft Enginemkhairuladha100% (1)

- THE-EVOLUTION-OF-CARS-1Dokument32 SeitenTHE-EVOLUTION-OF-CARS-1freddieestillore104Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rearwin Cloudster Monoplane (1940)Dokument4 SeitenRearwin Cloudster Monoplane (1940)CAP History Library100% (1)

- Wright J-5Dokument4 SeitenWright J-5Mauro ContiNoch keine Bewertungen

- LAA - Light Aviation - October 2012 - Over The HedgeDokument2 SeitenLAA - Light Aviation - October 2012 - Over The HedgecluttonfredNoch keine Bewertungen

- Super CavitationDokument25 SeitenSuper Cavitationpp2030100% (2)

- BHP Loco Update2Dokument10 SeitenBHP Loco Update2Ben Hudson100% (1)

- NZ Aviation News - Fred Turns 50 - November 2013Dokument1 SeiteNZ Aviation News - Fred Turns 50 - November 2013cluttonfredNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amphibious Vehicle: Larc-V Vehicle Craft AmphibianDokument19 SeitenAmphibious Vehicle: Larc-V Vehicle Craft AmphibianPravat Kumar SahuNoch keine Bewertungen

- British Marine Industry and the Rise of Diesel EnginesDokument30 SeitenBritish Marine Industry and the Rise of Diesel Enginesravi_92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Marine Propulsion For Small CraftsDokument71 SeitenMarine Propulsion For Small CraftsGermán Aguirrezabala100% (1)

- Eldred AnecdoteDokument14 SeitenEldred Anecdoteandrew_harve100% (1)

- DingfelderDokument3 SeitenDingfelderRemi DrigoNoch keine Bewertungen

- DAC Design & DevelopmentDokument16 SeitenDAC Design & DevelopmentasdfkoipnNoch keine Bewertungen

- History: Bramah Joseph Diplock Traction EngineDokument6 SeitenHistory: Bramah Joseph Diplock Traction EngineDev SandhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kiwi Aircraft Images - D17S StaggerwingDokument3 SeitenKiwi Aircraft Images - D17S StaggerwingIceman 29100% (1)

- Royal Enfield - Organization Analysis - 125279026 PDFDokument22 SeitenRoyal Enfield - Organization Analysis - 125279026 PDFManish Nani100% (1)

- 25 Things You DidnDokument1 Seite25 Things You DidnKirk JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classic British MotorcyclesDokument38 SeitenClassic British MotorcyclesFonthill Media86% (7)

- Chapter 2B - Chassis ConstructionDokument54 SeitenChapter 2B - Chassis Constructionfaris iqbal100% (1)

- Jaguar 75 BookDokument34 SeitenJaguar 75 BookperegimferrerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seminar FormatDokument25 SeitenSeminar Formatstan leeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motor Sports Unit-1Dokument88 SeitenMotor Sports Unit-1Prince BadhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flat-Eight Engine: Design Use in Automobiles Use in Aircraft Use in Marine Vessels See Also ReferencesDokument5 SeitenFlat-Eight Engine: Design Use in Automobiles Use in Aircraft Use in Marine Vessels See Also ReferencesAve FenixNoch keine Bewertungen

- Griffiths Diesel EngineDokument30 SeitenGriffiths Diesel Enginesunahsuggs50% (2)

- R/C Soaring Digest - Jul 2005Dokument40 SeitenR/C Soaring Digest - Jul 2005Aviation/Space History LibraryNoch keine Bewertungen

- R/C Soaring Digest - Dec 2011Dokument98 SeitenR/C Soaring Digest - Dec 2011Aviation/Space History Library0% (1)

- History MFV Elinor Viking Was An Aberdeen Trawler That OperatedDokument3 SeitenHistory MFV Elinor Viking Was An Aberdeen Trawler That OperatedJerome BrusasNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Helicopter Museum: Newsletter Vol. 3Dokument8 SeitenThe Helicopter Museum: Newsletter Vol. 3John Clews100% (1)

- The Corvette and ZoraDokument5 SeitenThe Corvette and Zoraapi-313424514Noch keine Bewertungen

- (Osprey) - (Modelling Manuals 011) - WW 2 Soft-Skinned Military VehiclesDokument66 Seiten(Osprey) - (Modelling Manuals 011) - WW 2 Soft-Skinned Military Vehiclesdynokiev90% (10)

- Lesson 1 IntroductionDokument15 SeitenLesson 1 Introductiondeepak9996Noch keine Bewertungen

- Great Cars of All Time: Fascinating stories of the origin, development, and famous feats of the world's most exciting automobilesVon EverandGreat Cars of All Time: Fascinating stories of the origin, development, and famous feats of the world's most exciting automobilesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geodetic Aircraft Structure: A Proven Wooden Design for HomebuildersDokument8 SeitenGeodetic Aircraft Structure: A Proven Wooden Design for HomebuildersUroš RoštanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supermarine Southampton: The Flying Boat that Made R.J. MitchellVon EverandSupermarine Southampton: The Flying Boat that Made R.J. MitchellNoch keine Bewertungen

- American Aviation Historical SocietyDokument16 SeitenAmerican Aviation Historical SocietyCAP History LibraryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flight. 453: OCTOBER 3T, 1935Dokument1 SeiteFlight. 453: OCTOBER 3T, 1935seafire47Noch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction .. 2. Industry Overview 3. Purpose of The Study . 4. Research Objectives . 5. Research MethodologyDokument8 SeitenIntroduction .. 2. Industry Overview 3. Purpose of The Study . 4. Research Objectives . 5. Research MethodologyGaurav GangwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Royal EnfieldDokument4 SeitenRoyal Enfieldbalasubramanian979Noch keine Bewertungen

- Wankel EngineDokument28 SeitenWankel EngineSARATH KRISHNAKUMARNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sprint car racing: high-powered dirt track racingDokument5 SeitenSprint car racing: high-powered dirt track racingNeville DickensNoch keine Bewertungen

- The First Automobile: Double-Pivot SteeringDokument3 SeitenThe First Automobile: Double-Pivot SteeringAlona Jean ParNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engine: Metric HP PS Maybach HL 230 P30Dokument4 SeitenEngine: Metric HP PS Maybach HL 230 P30Austin LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ship Propulsion - Darrens 17 Sep 2018Dokument20 SeitenShip Propulsion - Darrens 17 Sep 2018Muhammad Indra Dwi KomaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theory of MotorcycleDokument26 SeitenTheory of MotorcycleArun K Gupta100% (1)

- Thirty-First Army (Japan)Dokument2 SeitenThirty-First Army (Japan)HeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Balfour Declaration of 1926 defined Dominions' statusDokument3 SeitenBalfour Declaration of 1926 defined Dominions' statusHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ludovico BreaDokument2 SeitenLudovico BreaHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uranium Bubble of 2007Dokument2 SeitenUranium Bubble of 2007HeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elger (Crater)Dokument2 SeitenElger (Crater)HeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alexander Crichton of BrunstaneDokument5 SeitenAlexander Crichton of BrunstaneHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Historic Lawtonville Baptist ChurchDokument2 SeitenHistoric Lawtonville Baptist ChurchHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spilling SaltDokument2 SeitenSpilling SaltHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indiana State Sycamores Women's BasketballDokument4 SeitenIndiana State Sycamores Women's BasketballHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vulca: 1 ReferencesDokument2 SeitenVulca: 1 ReferencesHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Winston SchoolDokument2 SeitenThe Winston SchoolHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ATi Radeon R300 SeriesDokument5 SeitenATi Radeon R300 SeriesHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Slave Point FormationDokument2 SeitenSlave Point FormationHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bocca BaciataDokument2 SeitenBocca BaciataHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aleksandr DrozdenkoDokument2 SeitenAleksandr DrozdenkoHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pribislaw IDokument2 SeitenPribislaw IHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cumming School of MedicineDokument3 SeitenCumming School of MedicineHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ATi Radeon R300 SeriesDokument5 SeitenATi Radeon R300 SeriesHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Genova (1953 Film)Dokument3 SeitenGenova (1953 Film)HeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Living Oceans SocietyDokument4 SeitenLiving Oceans SocietyHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jackson, California: 1 Geography and GeologyDokument5 SeitenJackson, California: 1 Geography and GeologyHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Genova (1953 Film)Dokument3 SeitenGenova (1953 Film)HeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Living Oceans SocietyDokument4 SeitenLiving Oceans SocietyHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tin (IV) IodideDokument2 SeitenTin (IV) IodideHeikki100% (1)

- Anglo Powhatan WarsDokument6 SeitenAnglo Powhatan WarsHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canadian National Vimy MemorialDokument19 SeitenCanadian National Vimy MemorialHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electronic Bill PaymentDokument2 SeitenElectronic Bill PaymentHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unforgettable (1996 Film)Dokument5 SeitenUnforgettable (1996 Film)HeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greg HughesDokument3 SeitenGreg HughesHeikkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MPC-006 DDokument14 SeitenMPC-006 DRIYA SINGHNoch keine Bewertungen

- EVOLUTION Class Notes PPT-1-10Dokument10 SeitenEVOLUTION Class Notes PPT-1-10ballb1ritikasharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fajar Secondary Sec 3 E Math EOY 2021Dokument16 SeitenFajar Secondary Sec 3 E Math EOY 2021Jayden ChuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- YOKOGAWADokument16 SeitenYOKOGAWADavide ContiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mfz-Odv065r15j DS 1-0-0 PDFDokument1 SeiteMfz-Odv065r15j DS 1-0-0 PDFelxsoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- G 26 Building Using ETABS 1673077361Dokument68 SeitenG 26 Building Using ETABS 1673077361md hussainNoch keine Bewertungen

- 60 GHZDokument9 Seiten60 GHZjackofmanytradesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specifications Sheet ReddyDokument4 SeitenSpecifications Sheet ReddyHenry CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cricothyroidotomy and Needle CricothyrotomyDokument10 SeitenCricothyroidotomy and Needle CricothyrotomykityamuwesiNoch keine Bewertungen

- IMRAD - G1 PepperDokument13 SeitenIMRAD - G1 PepperRomero, Ken Angelo B.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 Cost MinimizationDokument6 SeitenChapter 4 Cost MinimizationXavier Hetsel Ortega BarraganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whatever Happens, Happens For Something Good by MR SmileyDokument133 SeitenWhatever Happens, Happens For Something Good by MR SmileyPrateek100% (3)

- UNIT-2 Design of Spur GearDokument56 SeitenUNIT-2 Design of Spur GearMarthandeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Dedication of the Broken Hearted SailorDokument492 SeitenThe Dedication of the Broken Hearted SailorGabriele TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qualtrics Ebook Employee Lifecycle Feedback Apj - q8uL5iqE4wt2ReEuvbnIwfG4f5XuMyLtWvNFYuM5Dokument18 SeitenQualtrics Ebook Employee Lifecycle Feedback Apj - q8uL5iqE4wt2ReEuvbnIwfG4f5XuMyLtWvNFYuM5RajNoch keine Bewertungen

- College of Medicine & Health SciencesDokument56 SeitenCollege of Medicine & Health SciencesMebratu DemessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electrical EngineerDokument3 SeitenElectrical Engineer12343567890Noch keine Bewertungen

- BMW Mini COoper Installation InstructionsDokument1 SeiteBMW Mini COoper Installation InstructionsEdiJonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supply Chain Management: Tata Tea's Global OperationsDokument15 SeitenSupply Chain Management: Tata Tea's Global OperationsAmit Halder 2020-22Noch keine Bewertungen

- IruChem Co., Ltd-Introduction of CompanyDokument62 SeitenIruChem Co., Ltd-Introduction of CompanyKhongBietNoch keine Bewertungen

- Desiderata: by Max EhrmannDokument6 SeitenDesiderata: by Max EhrmannTanay AshwathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Techniques for Studying FossilsDokument11 SeitenTechniques for Studying FossilsP. C. PandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Baptismal Liturgy in The Easter Vigil According To The Sacramentary of Fulda (10th Century)Dokument7 SeitenThe Baptismal Liturgy in The Easter Vigil According To The Sacramentary of Fulda (10th Century)Henry DonascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schroedindiger Eqn and Applications3Dokument4 SeitenSchroedindiger Eqn and Applications3kanchankonwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- GSM Modernization Poster2Dokument1 SeiteGSM Modernization Poster2leonardomarinNoch keine Bewertungen

- ATEX Certified FiltersDokument4 SeitenATEX Certified FiltersMarco LoiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SDE1 V1 G2 H18 L P2 M8 - SpecificationsDokument1 SeiteSDE1 V1 G2 H18 L P2 M8 - SpecificationsCleverson SoaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Principles of Local GovernmentDokument72 SeitenBasic Principles of Local GovernmentAnne Camille SongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anxiolytics Sedatives Hypnotics Pharm 3Dokument38 SeitenAnxiolytics Sedatives Hypnotics Pharm 3Peter Harris100% (1)

- CBSE Worksheet-01 Class - VI Science (The Living Organisms and Their Surroundings)Dokument3 SeitenCBSE Worksheet-01 Class - VI Science (The Living Organisms and Their Surroundings)Ushma PunatarNoch keine Bewertungen