Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Vitamin K2 and The Calcium Connection

Hochgeladen von

C JayCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Vitamin K2 and The Calcium Connection

Hochgeladen von

C JayCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

VITAMIN K2 &

THE CALCIUM CONNECTION

CALCIUM INTAKE REQUIRES ADEQUATE

VITAMIN K2 TO PROTECT AND

PROMOTE CARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH

[ International Science and Health Foundation ]

www.ishf.eu

OVERVIEW

Inadequate calcium intake can lead to decreased Calciums ability to lower blood pressure13 and lower

bone mineral density, which can increase the risk blood cholesterol levels14-16 contributes to heart health.

of bone fractures. Supplemental calcium pro- Indeed, a prospective cohort study (i.e., observation

motes bone mineral density and strength and can of individuals over time) of postmenopausal women

prevent osteoporosis (i.e., porous bones), par- from Iowa connected higher calcium intake to lower

ticularly in elderly and postmenopausal women.1, 2 risk of death due to heart disease through restricted

However, recent scientific evidence suggests that blood supply.17 Meanwhile, a prospective longitudinal

elevated calcium consumption accelerates calcium cohort study (i.e. observation of individuals over long

deposits in blood vessel walls and soft tissues, which period of time) in Sweden reported that older women

may raise the risk for heart disease3-8 (see Table 2). at 1,400 mg/day calcium intakes were at higher risk

for heart disease death than women taking 600-

In contrast, vitamin K2 has been shown to prevent 1,000 mg/day.6 However, other prospective studies

arterial calcification and arterial stiffening9, 10, which have revealed no link between high calcium intake

means increased vitamin K2 amounts in the body could and cardiac events18-20 and cardiac death.18, 21, 22 The

be a means of lowering calcium-associated health risks. effects of calcium on stroke are also inconsistent since

With the human diet lacking vitamin K2, some publications associate high calcium intakes with

taking vitamin K2 supplements is one way to secure lowered stroke risk, while others found no connection

adequate intake. By striking the right balance between between the calcium and incidence of stroke.19, 20

calcium and vitamin K2 intake, it may be possible

to fight osteoporosis and at the same time prevent Most recently, several studies have cast doubt on

the calcification and stiffening of the arteries. A new the notion that more is better when it comes to

clinical study pending publication with vitamin K2 calcium intake and cardiovascular disease preven-

supplementation showed an improvement in arte- tion.23

rial elasticity and regression in age-related arterial

stiffening (data pending publication).50 Most impor- TABLE 1

tant, vitamin K2 could optimize calcium utilization in

the body preventing any potential negative health

CALCIUM FACTS

impacts associated with increased calcium intake.

Calcium is the most abundant nutrient in

humans.

Calcium serves many important roles in the human

body (see Table 1). It provides structure and hard-

Bones and teeth store most of the calcium

ness to bones and teeth; allows muscles to contract

(99%), where it provides hardness and

and nerves to send signals; makes blood vessels ex- structure.

pand and contract; helps blood to clot; and supports

protein function and hormone regulation.11 Average Muscles, nerves and blood vessels depend

daily recommended intakes of calcium differ with age, on the remaining 1% of calcium for their

with children, teens and the aging population need- function structure.

ing the most. Even though dairy products represent a

Low calcium intake is linked to fractures,

rich source of calcium, approximately 43% of the U.S. stroke and fatal ischemic heart disease in

population and 70% of older women regularly take the elderly.

calcium supplements.12 Calcium supplementation is

supported by several studies backing its benefits for The Paradox: supplemental calcium has

bone health and osteoporosis prevention, as well as also been linked to higher risk of ischemic

heart disease and stroke incidence in some

for overall health.

studies. It has also been linked to overall

health and cardiovascular mortality rates,

as well as increased heart disease risk.

01 [ International Science and Health Foundation ]

www.ishf.eu

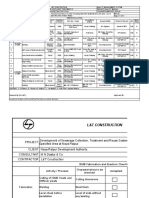

TABLE 2

POPULATION- MAIN

TITLE CHARACTERISTICS FINDINGS REFERENCE

HEALTH CONCERNS WITH CALCIUM SUPPLEMENTATION

1. Use of calcium supplements and the risk of coronary heart disease Increased risk of CVD with calcium or

in 52-62-year-old women: The Kuopio Osteoporosis Risk Factor and Women (52-62 y) calcium+vitamin D Supplement (7)

Prevention Study. Mauritas. 2009.

2. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and Men and women Increased heart attack risk with calcium

cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010. (>40 y) (3)

Supplements

3. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardio-

Postmenopausal Calcium or calcium+vitamin D Supple-

vascular events: reanalysis of the Womens Health Initiative limited (4)

women ments increases heart attack risk

access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011.

4. Associations of dietary calcium intake and calcium supplementation Increased risk of heart attack with cal-

with myocardial infarction and stroke risk and overall cardiovascular Men and women

cium Supplements and even higher risk (18)

mortality in the Heidelberg cohort of the European Prospective Inves- (35-64 y)

when taken without other Supplements

tigation into Cancer and Nutrition study (EPIC-Heidelberg).

Am J Clin Nutr. 2003.

5. Long term calcium intake and rates of all-cause and cardiovascular (6)

Women (>40 y) High calcium intake is linked to higher

mortality: community based prospective longitudinal cohort study. death rates from all causes and CVD

BMJ. 2013.

6. Dietary and supplemental calcium intake and cardiovascular dis- Men and women High supplemental calcium increases (8)

ease mortality: the National Institutes of Health-AARP diet and (50-71 y) risk of CVD death in men only

health study. JAMA. 2013.

POPULATION- MAIN

TITLE CHARACTERISTICS FINDINGS REFERENCE

H E A LT H B E N E F I T S O F V I TA M I N K 2 S U P P L E M E N TAT I O N

7. Japanese fermented soybean food as the major determinant of the Postmenopausal Increased intake of MK-7 helps to reduce

large geographic difference in circulating levels of vitamin K2: pos- women hip fracture risk (40)

sible implications for hip-fracture risk. Nutrition. 2001.

8. Dietary intake of menaquinone is associated with a reduced risk of Men and women High menaquinone intake reduces risk of

(>55 y) CVD mortality, all-cause mortality and (10)

coronary heart disease: the Rotterdam Study. J Nutr. 2004.

severe aortic calcification

9. Regression of warfarin-induced medial elastocalcinosis by high in- Rats Vitamin K2 reduces aortic calcium levels

take of vitamin K in rats. Blood. 2007. and increases arterial distensibility in an (43)

induced arterial calcification model

10. High dietary menaquinone intake is associated with reduced coro- Postmenopausal High dietary vitamin K2 reduces coro- (9)

nary calcification. Atherosclerosis. 2009. women nary calcium deposits

11. A high menaquinone intake reduces the incidence of coronary Women (49-70 y) High vitamin K2 intake (MK-7, -8, -9) is (45)

heart disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009. linked to lower CVD risk

Hemodialysis Vitamin K2 Supplementation improves

12. Effect of vitamin K2 supplementation on functional vitamin K

patients (18 y) activity of a protein involved in calcium (48)

deficiency in hemodialysis patients: a randomized trial.

removal in arterial wall (MK-7) (Me-

Am J Kidney Dis. 2012.

naQ7)

13. Three-year low-dose menaquinone-7 supplementation helps Postmenopausal Mk-7 Supplement may help to prevent (49)

decrease bone loss in healthy postmenopausal women. women bone loss (MenaQ7)

Osteoporosis Int. 2013.

14. Menaquinone-7 supplementation improves vascular properties Postmenopausal MK-7 Supplement regressed age-related (50)

in healthy postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. women arterial stiffening (MenaQ7)

Submitted. Pending.

[ International Science and Health Foundation ] 02

www.ishf.eu

OVERVIEW

A study published by Xiao et. al. discussed the In patients with kidney failure, supplemental cal-

outcome of the National Institutes of Health cium has also been linked to increased hard-

(NIH)AARP Diet and Health Study, which eva- ening of the arteries through calcification, as

luated the role of supplemental calcium on car- well as higher mortality.24, 25 A meta-analysis

diovascular health.8 This prospective study in- (i.e., combining and analyzing the results from dif-

volved a large group of 219,059 men and 169,170 ferent studies) of kidney disease also linked calcium

women whose health was tracked over 12 years. supplementation with a 22% increased risk of car-

The researchers found that men but not diovascular death.26

women taking more than 1,000 mg/day of cal-

cium supplements had a 20% higher risk of total A possible explanation for the negative

cardiovascular death compared to those taking effects of high dose, long-term calcium intake on

no calcium supplements. cardiovascular health is that it renders the nor-

mal homeostatic control of blood calcium concen-

Other published studies have found a detrimen- trations ineffective.6

tal impact of calcium supplementation on wom-

ens cardiovascular health, too. The data from the In otherwords, increased blood calcium levels have been

Womens Health Initiative showed that those tak- correlated with elevated blood clotting and cal-

ing 1,000 mg/day in the form of calcium supple- cium deposition in blood vessels leading to arterial

ments with or without the addition of 400 IU/day hardening, both of which increase the risk of heart

of vitamin D increased their risk of cardiovascular disease (see Figure 1).4, 8, 27, 28

events by 15-22%, especially in women

who at the beginning of study did not FIGURE 1: ATHEROSCLEROSIS DEVELOPMENT

take calcium supplements . Moreover,

4

a 24% increased risk of coronary heart

disease was detected in a group of

10,555 Finish women who used calci-

um supplements with or without vita-

min D.7 [ CALCIFICATION ]

Also, researchers from the European

Prospective Investigation into Cancer

and Nutrition study (EPIC-Heidelberg)

concluded that in the 23,980 partici-

pants, those regularly taking a calcium

supplement had an 86% higher risk

for heart attack compared to those

not taking a supplement.5 The effect

was even more pronounced when no

supplements other than calcium were

taken heart attack risk more than

Stiffening of arteries, also called atherosclerosis, is the primary cause of heart disease.

doubled in these cases. It is triggered, among other factors, by calcium deposits in blood vessels, making them pro-

gressively stiff and narrow, which hinders normal blood flow and leads to heart and car-

diovascular disease.

03 [ International Science and Health Foundation ]

www.ishf.eu

Eighty-four years ago while investigating TABLE 3

the effects of a low-fat diet fed to chickens,

V I TA M I N K 2

Danish scientist Henrik Dam discovered vita-

min K. He found that bleeding tendencies in FACTS

chickens could be prevented when a regular VITAMIN K2 (menaquinones)

fat diet was restored and vitamin K was add-

ed to their diet. From this point forward, vita-

min K became known as the coagulation vita-

Vitamin K2 is a fat-soluble substance.

min the K coming from the German word

Koagulation (see Table 3).29

It can render special proteins (vitamin

Later it was found that this fat-soluble com- K-dependent proteins) functional by the

pound needed for blood clotting exists in addition of carboxyl (-COOH) groups.

two forms: phylloquinone (vitamin K1) and

menaquinone (vitamin K2) (see Figure 2).30 Vitamin K2 is needed for normal blood

coagulation (in German and Nordic lan-

Vitamin K1 is made in plants and algae green guages: Koagulation from where the K

leafy vegetables are a particularly rich source originated).

of it. On the other hand, bacteria generate

vitamin K2, which can also be found in meat, It is made by bacteria, which give fermented

dairy, eggs and fermented foods such as foods like cheese and the Japanese natto

cheese, yogurt and natto (a Japanese dish of (fermented soybeans) a high K2 content.

fermented soybeans).31, 32

01

Vitamin K2 is also involved in bone forma-

tion and repair.

Even though the side chains of isoprenoid

units of vitamin K differ in length from 1 to 14

repeats, they are all used by the enzyme It is associated with reduced risk for heart

disease and hip fractures.

-glutamate carboxylase to activate a specific

set of proteins, including proteins involved in

blood coagulation, bone formation and inhibi- Vitamin K2 can prevent and even reverse

tion of soft tissue calcification. blood vessel calcium deposits (i.e., calcifi-

cation) and increase flexibility.

Vitamin K (K1 and K2) is essential in main-

taining blood homeostasis and optimal bone

and heart health through the role it plays in

inducing calcium use by proteins.

Vitamin K, particularly vitamin K2, is essen-

tial for calcium utilization, helping build strong

bones and inhibit arterial calcification.

[ International Science and Health Foundation ] 04

www.ishf.eu

VITAMIN K2

FIGURE 2: CHEMICAL STRUCTURE OF VITAMIN K1 & K2 (MK-4 & MK-7)

PHYLLOQUINONE (K 1 )

MK-4 (K 2 )

MK-7 (K 2 )

Different types of vitamin K vary in length and saturation (double versus single bonds) of the isoprenoid side chain.

Vitamin K2/Menaquinones are abbreviated as MK-n, where n symbolizes the number of isoprene repeats (C5H8).

ACHIEVING If there is a lack of vitamin K2 over a long period

of time, then calcium will not be integrated into

OPTIMAL the bone and poor bone quality will result.

B O N E H E A LT H

Populations that consume enough vitamin K2

have stronger, healthier bones. The Western diet,

Bone relies on calcium for its structure, function and however, does not contain sufficient vitamin K2

health. It is also a living tissue that contains blood leaving many people vitamin K2-deficient.34, 35

vessels, nerves and cells. Bone structure is secured

by two type of cells osteoblasts which build bones Children in particular need more vitamin K2

and osteoclasts which remodel bones (see Figure 3). since they have a much higher bone metabo-

Osteoblasts produce the protein osteocalcin, which lism than adults. From the late 20s to mid-30s

needs to be activated by vitamin K2 to bind calcium peak bone mass is reached, after which bone

to the bones mineral matrix, thereby strengthening mineral content slowly diminishes. Thus, the high-

the skeleton.33 er the peak bone mass attained at a younger

age, the longer the bone mass can be preserved

(see Figure 4).

05 [ International Science and Health Foundation ]

www.ishf.eu

Population-based studies and FIGURE 3: HEALTHY BONE STRUCTURE VS. POOR BONE STRUCTURE

clinical trials have linked higher

blood vitamin K2 concentra-

tions to stronger bones. Further,

studies in adults have revealed

that vitamin K2 supplementa-

tion helps promote bone health

and maintain bone mineral den-

sity.36-38, 42

A study in children also

showed that improving vitamin

K2 intake over a two-year pe-

Bone is a living material comprised of a hard outer shell and spongy inner tissue structured to

riod led to stronger and denser withstand the physical stress of bearing body mass. The entire skeleton is replaced approximate-

bones.39 ly every seven years due to the remodelling action of osteoclasts. Vitamin K2 is needed for acti-

vation of proteins (e.g., osteocalcin) invovled in bone formation, which is why a diet low in vitamin

K2 reduces bone strength and density.

Form definitely matters.

In fact, studies on natto

a vitamin K2 rich traditio-

nal Japanese food based on fermented soy FIGURE 4: CALCIUM LOSS INCREASES WITH AGE

beans support the importance of vitamin K2

in the form of menaquinone with seven iso- 1 Men

prene residues (MK-7). Kaneki and colleagues 1500

have showed that increased consumption of 1 3

MK-7 leads to more activated osteocalcin,

Total mass of calcium in

which is linked to increased bone matrix forma- Women

the skeleton (grams)

1000

tion and bone mineral density, and therefore 2

a lower risk of hip fracture.40 3

These results were confirmed in a three-year 500

study with 944 women (aged 20-79) showing 1. Peak bone mass

2. Menopausual bone loss

that intake of MK-7-rich natto helps preserve

3. Loss of bone mass with increasing age

bone mineral density.41

0

20 40 60 80 100

One recent double-blind, randomized clinical Age (years)

trial investigated the effect of supplemental

MK-7 (MenaQ7) over three years in a group

of 244 post-menopausal Dutch women.49

Researchers found that a daily dose of 180

mcg was enough to improve bone mineral

density, bone strength and cardiovascular

health. They also showed that achieving a

clinically relevant improvement required at

least two years of supplementation.

[ International Science and Health Foundation ] 06

www.ishf.eu

VITAMIN

VITAMIN K2

K2

THE IDEAL

S TAT E O F

H E A R T H E A LT H

Adequate intake of vitamin K2 has been shown FIGURE 5: HIGH VITAMIN K2 CONSUMPTION PROMOTES

to lower the risk of vascular damage because it CARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH

activates Matrix Gla Protein (MGP), which inhibits

calcium from depositing in the vessel walls (arte-

rial calcification).

The Rotterdam Study

Aorta Calcification

Hence, calcium is available for other multiple roles in

Risk for event (Hazard rati o)

120 Cardiovascular mortality

the body, leaving the arteries healthy and flexible.43 All-cause mortality

100

However, vitamin K deficiency results in inadequate 80

activation of MGP, which greatly impairs the calci-

60

um removal process and increases the risk of blood

40

vessel calcification.44 Since this process occurs in

20

the vessel wall, it leads to the wall thickening via cal-

0

cified plaques (i.e., typical atherosclerosis progre- <21

21-32 >32

ssion), which is associated with higher risk of car- Dietary vitamin K2 intak e (g/day)

diovascular events.

The population-based Rotterdam study evalu-

ated 4807 healthy men and women over age After eight years, the data showed that high

55 and the relationship between dietary intake intake of natural vitamin K2, but not vitamin K1,

of vitamin K and aortic calcification, heart dis- helps protect against cardiovascular events; for

ease and all-cause mortality.10 The study re- every 10 mcg of vitamin K2 (in the forms of MK-

vealed that high dietary intake of vitamin K2 7, MK-8 and MK-9) consumed, the risk of coro-

(at least 32 mcg per day) and not vitamin K1, re- nary heart disease was reduced by 9%.

duced arterial calcification by 50%, cardiovascular

death by 50%, and all-cause mortality by 25% (see

Figure 5).

These findings were supported by another popula-

tion-based study with 16,000 healthy women (aged

49-70) from the Prospect-EPIC cohort population.45

07 [ International Science and Health Foundation ]

www.ishf.eu

A study on 564 post-menopausal women FIGURE 6: CAROTID ARTERY DISTENSIBILITY IMPROVED

also revealed that vitamin K2 intake de-

creases coronary calcification, whereas

vitamin K1 does not.9

A study pending publication on 244 post-

menopausal women supplemented with DATA PENDING PUBLICATION.

180 mcg of vitamin K2 as MK-7 actually PLEASE CONTACT

showed a significant improvement in

INTERNATIONAL SCIENCE AND HEALTH

cardiovascular health as measured by

ultra-sound and pulse-wave velocity, which FUNDATION FOR MORE INFORMATION.

are recognized standard measurements

for cardiovascular health. In this trial,

carotid artery distensibility (i.e., elasticity)

the ability for a blood vessel to stretch or

dilate was significantly improved over

a three-year period as compared to the

placebo group (see Figure 6). Also, pulse-

FIGURE 7: CAROTID & FEMORAL ARTERIES PULSE WAVE

wave velocity was significantly decreased VELOCITY IMPROVED

in the vitamin K2 (MK-7) group, but not the

placebo group, demonstrating an increase

in the elasticity and reduction in age-

related arterial stiffening (see Figure 7).50

01

DATA PENDING PUBLICATION.

PLEASE CONTACT

INTERNATIONAL SCIENCE AND HEALTH

FUNDATION FOR MORE INFORMATION.

[ International Science and Health Foundation ] 08

www.ishf.eu

VITAMIN K2 & CALCIUM:

P E R F EC T TO G E T H E R

KEEP THE CALCIUM

...JUST ADD

V I TA M I N K 2

The studies presented in Table 2 illus- FIGURE 8: VITAMIN K DEFICIENCIES IN WESTERN DIETS

trate that high calcium consumption

helps strengthen the skeleton but at

the same time may increase the risk

of heart disease due to arterial calci- K1 K2

fication.3-8, 16

400

Dysfunctional calcium-regulatorypro-

teins such as MGP correlate with the

development of arterial calcification. 200

g

To render these proteins active, a suf-

ficient amount of vitamin K2 has to be

present in the body.46 If at least 32 mcg

0

of vitamin K2 is present in the diet, then Junk food Western healthy Japanese diet

the risk for blood vessel calcification diet

and heart problems is significantly low-

ered10 and elasticity of the vessel wall

is increased.47 On the contrary, if less

vitamin K2 is present in the diet, then

cardiovascular problems may arise.

In general, the typical Western diet

contains insufficient amounts of vitamin K2 to It appears that suboptimal vitamin K2

adequately activate MGP, which means about 30% levels in the body may disadvantage the vitamin

of vitamin K2-activated proteins remain inactive. K2-dependent activation of specific proteins.

This amount only increases with age. If these proteins cannot perform their function

by keeping calcium in the bones and preventing

Vitamin K, especially as vitamin K2, is nearly calcium deposits in soft tissues (e.g. arterial walls)

non-existent in junk food, and even in a healthy during situations of increased calcium intake,

Western diet. The only exception seems to be then general health and in particular cardio-

the Japanese diet, particularly in the portion vascular health may suffer due to an inefficient

of the population consuming high quantities of and misdirected utilization of calcium in the body.

vitamin k-rich foods, such as natto (see Figure 8).

09 [ International Science and Health Foundation ]

www.ishf.eu

CONCLUSION TABLE 4

I M P O R TA N C E O F

C A L C I U M + V I TA M I N K 2

Dietary calcium is linked to many benefits, es-

pecially bone health. This is why recommended

daily intakes for calcium have been established. At elevated levels, calcium may increase

Because diets often fall short of these guidelines, the risk for heart disease, possibly by

forming calcium deposits in blood vessels.

in particular in individuals with higher needs

(e.g. children, the elderly and postmenopausal Vitamin K2 has the ability to reverse arterial

women), dietary supplementation can help ad- stiffening since it is a key regulator of the

dress the bodys demands. Although the study proteins that are involved in calcium use.

outcomes of high calcium consumption are con-

troversial, several studies do suggest caution Vitamin K2 might therefore neutralize the

potential health problems associated with

when it comes to over supplementing, especially

high calcium intakes.

since some evidence points to health problems

at elevated levels.3-8

Calcium taken together with vitamin K2

may improve bone and vascular health.

This issue could be remedied, however, if the right

amount of vitamin K2 is added to a high calcium

regimen. Vitamin K2 promotes arterial flexibility

by preventing arterial calcium accumulation10,

43, 48, 50

, which could correct the imbalance of

calcium in the body. Thus, calcium in tandem with

vitamin K2 may well be the solution for bringing

necessary bone benefits while circumventing an

increased risk for heart disease.

[ International Science and Health Foundation ] 10

www.ishf.eu

REFERENCES

1. Cumming RG, Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, et al. Calcium intake and 15. Major GC, Alarie F, Dore J, et al. Supplementation with calcium +

fracture risk: results from the study of osteoporotic fractures. Am J vitamin D enhances the beneficial effect of weight loss on plasma lipid

Epidemiol. 1997;145:926-34. and lipoprotein concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:54-9.

2. Hodgson SF, Watts NB, Bilezikian JP, et al. American Association 16. Reid IR, Mason B, Horne A, et al. Effects of calcium supplementation

of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for on serum lipid concentrations in normal older women: a randomized

the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: 2001 controlled trial. Am J Med. 2002;112:343-7.

edition, with selected updates for 2003. Endocr Pract. 2003;9:544- 17. Bostick RM, Kushi LH, Wu Y, et al. Relation of calcium, vitamin D, and

64. dairy food intake to ischemic heart disease mortality among postmeno-

3. Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, et al. Effect of calcium supple- pausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:151-61.

ments on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: 18. Al-Delaimy WK, Rimm E, Willett WC, et al. A prospective study of

meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3691. calcium intake from diet and supplements and risk of ischemic heart

4. Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A, et al. Calcium supplements with or disease among men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:814-8.

without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the 19. Marniemi J, Alanen E, Impivaara O, et al. Dietary and serum vita-

Womens Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. mins and minerals as predictors of myocardial infarction and stroke in

BMJ. 2011;342:d2040. elderly subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;15:188-97.

5. Li K, Kaaks R, Linseisen J, et al. Associations of dietary calcium 20. Umesawa M, Iso H, Ishihara J, et al. Dietary calcium intake and risks

intake and calcium supplementation with myocardial infarction and of stroke, its subtypes, and coronary heart disease in Japanese: the

stroke risk and overall cardiovascular mortality in the Heidelberg JPHC Study Cohort I. Stroke. 2008;39:2449-56.

cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and

21. Umesawa M, Iso H, Date C, et al. Dietary intake of calcium in relation

Nutrition study (EPIC-Heidelberg). Heart. 2012;98:920-5.

to mortality from cardiovascular disease:

6. Michaelsson K, Melhus H, Warensjo Lemming E, et al. Long term the JACC Study. Stroke. 2006;37:20-6.

calcium intake and rates of all cause and cardiovascular

22. Van der Vijver LP, van der Waal MA, Weterings KG, et al. Calcium

mortality: community based prospective longitudinal cohort study.

intake and 28-year cardiovascular and coronary heart disease mortal-

BMJ. 2013;346:f228.

ity in Dutch civil servants. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21:36-9.

7. Pentti K, Tuppurainen MT, Honkanen R, et al. Use of calcium sup-

23. Reid IR. Cardiovascular effects of calcium supplements. Nutrients.

plements and the risk of coronary heart disease in 52-62-year-old

2013;5:2522-9.

women: The Kuopio Osteoporosis Risk Factor and Prevention Study.

24. Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, et al. Coronary-artery calcifica-

Maturitas. 2009;63:73-8.

tion in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing

8. Xiao Q, Murphy RA, Houston DK, et al. Dietary and supplemental

dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1478-83.

calcium intake and cardiovascular disease mortality:

25. Russo D, Miranda I, Ruocco C, et al. The progression of coronary

the National Institutes of Health-AARP diet and health study. JAMA

artery calcification in predialysis patients on calcium carbonate or seve-

Intern Med. 2013;173:639-46.

lamer. Kidney Int. 2007;72:1255.

9. Beulens JW, Bots ML, Atsma F, et al. High dietary menaquinone

26. Jamal SA, Vandermeer B, Raggi P, et al. Effect of calcium-based

intake is associated with reduced coronary calcification.

versus non-calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality in patients

Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:489-93.

with chronic kidney disease: an updated systematic review and meta-

10. Geleijnse JM, Vermeer C, Grobbee DE, et al. Dietary intake of analysis. Lancet. 2013.

menaquinone is associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart

27. Seely S. Is calcium excess in western diet a major cause of arterial

disease: the Rotterdam Study. J Nutr. 2004;134:3100-5.

disease? Int J Cardiol. 1991;33:191-8.

11. Edwards SL. Maintaining calcium balance: physiology and implica-

28. Wang L, Manson JE, Sesso HD. Calcium intake and risk of cardiovascular

tions. Nurs Times. 2005;101:58-61.

disease: a review of prospective studies and randomized clinical trials. Am

12. Bailey RL, Dodd KW, Goldman JA, et al. Estimation of total usual J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2012;12:105-16.

calcium and vitamin D intakes in the United States.

29. Zetterstrom R. H. C. P. Dam (1895-1976) and E. A. Doisy (1893-1986):

J Nutr. 2010;140:817-22.

the discovery of antihaemorrhagic vitamin and its impact on neonatal

13. van Mierlo LA, Arends LR, Streppel MT, et al. Blood pressure health. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:642-4.

response to calcium supplementation: a meta-analysis of

30. Beulens JW, Booth SL, van den Heuvel EG, et al. The role of menaqui-

randomized controlled trials. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:571-80.

nones (vitamin K2) in human health. Br J Nutr. 2013:1-12.

14. Ditscheid B, Keller S, Jahreis G. Cholesterol metabolism is af-

31. Bolton-Smith C, Price RJ, Fenton ST, et al. Compilation of a provisional

fected by calcium phosphate supplementation in humans.

UK database for the phylloquinone (vitamin K1) content of foods. Br J Nutr.

J Nutr. 2005;135:1678-82.

2000;83:389-99.

11 [ International Science and Health Foundation ]

www.ishf.eu

32. Schurgers LJ, Vermeer C. Determination of phylloquinone and 47. Braam LA, Hoeks AP, Brouns F, et al. Beneficial effects of vitamins

menaquinones in food. Effect of food matrix on circulating vitamin K D and K on the elastic properties of the vessel wall in postmenopausal

concentrations. Haemostasis. 2000;30:298-307. women: a follow-up study. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:373-80.

33. Shearer MJ, Newman P. Metabolism and cell biology of vitamin K. 48. Westenfeld R, Krueger T, Schlieper G, et al. Effect of vitamin K2 sup-

Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:530-47. plementation on functional vitamin K deficiency in hemodialysis patients:

34. Kalkwarf HJ, Khoury JC, Bean J, et al. Vitamin K, bone turnover, a randomized trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:186-95.

and bone mass in girls. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1075-80. 49. Knapen MH, Drummen NE, Smit E, et al. Three-year low-dose me-

35. OConnor E, Molgaard C, Michaelsen KF, et al. Serum percent- naquinone-7 supplementation helps decrease bone loss in healthy

age undercarboxylated osteocalcin, a sensitive measure of vitamin K postmenopausal women. Osteoporosis Int. 2013.

status, and its relationship to bone health indices in Danish girls. Br J 50. Proprietary study on MenaQ7 Vitamin K2 pending publication.

Nutr. 2007;97:661-6. Submitted. Contact NattoPharma, Oslo, for details.

36. Iwamoto J, Takeda T, Ichimura S. Effect of combined administra-

tion of vitamin D3 and vitamin K2 on bone mineral density of the lum-

bar spine in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Orthop Sci.

2000;5:546-51.

37. Shiraki M, Shiraki Y, Aoki C, et al. Vitamin K2 (menatetrenone) ef-

fectively prevents fractures and sustains lumbar bone mineral density

in osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:515-21.

38. Ushiroyama T, Ikeda A, Ueki M. Effect of continuous combined

therapy with vitamin K(2) and vitamin D(3) on bone mineral density

and coagulofibrinolysis function in postmenopausal women. Maturi-

tas. 2002;41:211-21.

39. van Summeren MJ, van Coeverden SC, Schurgers LJ, et al. Vita-

min K status is associated with childhood bone mineral content. Br J

Nutr. 2008;100:852-8.

40. Kaneki M, Hodges SJ, Hosoi T, et al. Japanese fermented soybean

food as the major determinant of the large geographic difference in

circulating levels of vitamin K2: possible implications for hip-fracture

risk. Nutrition. 2001;17:315-21.

41. Ikeda Y, Iki M, Morita A, et al. Intake of fermented soybeans, nat-

to, is associated with reduced bone loss in postmenopausal women:

Japanese Population-Based Osteoporosis (JPOS) Study. J Nutr.

2006;136:1323-8.

42. Knapen MH, Schurgers LJ, Vermeer C. Vitamin K2 supplementa-

tion improves hip bone geometry and bone strength indices in post-

menopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:963-72.

43. Schurgers LJ, Spronk HM, Soute BA, et al. Regression of warfa-

rin-induced medial elastocalcinosis by high intake of vitamin K in rats.

Blood. 2007;109:2823-31.

44. Cranenburg EC, Vermeer C, Koos R, et al. The circulating inactive

form of matrix Gla Protein (ucMGP) as a biomarker for cardiovascular

calcification. J Vasc Res. 2008;45:427-36.

45. Gast GC, de Roos NM, Sluijs I, et al. A high menaquinone intake re-

duces the incidence of coronary heart disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc

Dis. 2009;19:504-10.

46. Berkner KL, Runge KW. The physiology of vitamin K nutriture and

vitamin K-dependent protein function in atherosclerosis. J Thromb

Haemost. 2004;2:2118-32.

[ International Science and Health Foundation ] 12

www.ishf.eu

CALCIUM AND VITAMIN K2 | THE CALCIUM CONNECTION

International Science and Health Foundation

ul. Kunickiego 10

30-134 Krakw, Poland

Tel: +48 12 633 80 57

Fax: +48 12 631 07 59

E-mail: office@ishf.eu

www.ishf.eu

Katarzyna Maresz, PhD

President of Science and Health Foundation

E-mail: katarzyna.maresz@ishf.eu

CALCIUM AND VITAMIN K2 | THE CALCIUM CONNECTION

VITAMIN K2 & THE CALCIUM CONNECTION

presentation on NutraIngredients is

sponsored by NattoPharma.

For more information on Vitamin K2 and MenaQ7 Vitamin K2 please contact:

NattoPharma ASA

(head office)

Kirkeveien 59B

1363 Hvik, Norway

info@nattopharma.com

Tel: (+47) 40 00 90 08

NattoPharma USA, Inc.

(North American Subsidiary)

328 Amboy Avenue

Metuchen, NJ 08840, USA

info.US@nattopharma.com

Tel: (+1) 609-454-2992

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Honesty Really Is The Best PolicyDokument1 SeiteHonesty Really Is The Best PolicyC JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Make Sure She Replies To Your TextDokument1 SeiteHow To Make Sure She Replies To Your TextC JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Women's EmotionDokument1 SeiteWomen's EmotionC JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Fathers Daily Activities - Present TenseDokument1 SeiteMy Fathers Daily Activities - Present TenseC JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Don't You Say What You MeanDokument4 SeitenWhy Don't You Say What You MeanC Jay100% (2)

- Narrative Story Draft - My Stupid ExperienceDokument1 SeiteNarrative Story Draft - My Stupid ExperienceC JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Live On 24 HoursDokument35 SeitenHow To Live On 24 HoursC JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shafait Efficient Binarization SPIE08Dokument6 SeitenShafait Efficient Binarization SPIE08C JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adaptive Thresholding Algorithm: Based On Intelligent Block DetectionDokument11 SeitenAdaptive Thresholding Algorithm: Based On Intelligent Block DetectionC JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ni BlockDokument12 SeitenNi BlockC JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kinema TicsDokument3 SeitenKinema TicsC JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Variables in DMC 2008 Data TrainingDokument3 SeitenVariables in DMC 2008 Data TrainingC JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Speed and VelocityDokument23 SeitenSpeed and VelocityC Jay100% (1)

- Guide To SSL VPNs - Recommendations of The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)Dokument87 SeitenGuide To SSL VPNs - Recommendations of The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)C JayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eat That FrogDokument53 SeitenEat That FrogKarl PinedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Bench-Scale Decomposition of Aluminum Chloride Hexahydrate To Produce Poly (Aluminum Chloride)Dokument5 SeitenBench-Scale Decomposition of Aluminum Chloride Hexahydrate To Produce Poly (Aluminum Chloride)varadjoshi41Noch keine Bewertungen

- MolnarDokument8 SeitenMolnarMaDzik MaDzikowskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report DR JuazerDokument16 SeitenReport DR Juazersharonlly toumasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Positive Psychology in The WorkplaceDokument12 SeitenPositive Psychology in The Workplacemlenita264Noch keine Bewertungen

- Taoist Master Zhang 张天师Dokument9 SeitenTaoist Master Zhang 张天师QiLeGeGe 麒樂格格100% (2)

- Albert Roussel, Paul LandormyDokument18 SeitenAlbert Roussel, Paul Landormymmarriuss7Noch keine Bewertungen

- LFF MGDokument260 SeitenLFF MGRivo RoberalimananaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CTS2 HMU Indonesia - Training - 09103016Dokument45 SeitenCTS2 HMU Indonesia - Training - 09103016Resort1.7 Mri100% (1)

- Muscles of The Dog 2: 2012 Martin Cake, Murdoch UniversityDokument11 SeitenMuscles of The Dog 2: 2012 Martin Cake, Murdoch UniversityPiereNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test Bank For The Psychology of Health and Health Care A Canadian Perspective 5th EditionDokument36 SeitenTest Bank For The Psychology of Health and Health Care A Canadian Perspective 5th Editionload.notablewp0oz100% (37)

- Sanskrit Subhashit CollectionDokument110 SeitenSanskrit Subhashit Collectionavinash312590% (72)

- Table of Specification 1st QDokument5 SeitenTable of Specification 1st QVIRGILIO JR FABINoch keine Bewertungen

- What You Need To Know About Your Drive TestDokument12 SeitenWhat You Need To Know About Your Drive TestMorley MuseNoch keine Bewertungen

- 35 Electrical Safety SamanDokument32 Seiten35 Electrical Safety SamanSaman Sri Ananda RajapaksaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brahms Symphony No 4Dokument2 SeitenBrahms Symphony No 4KlausNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crisis of The World Split Apart: Solzhenitsyn On The WestDokument52 SeitenCrisis of The World Split Apart: Solzhenitsyn On The WestdodnkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in MAPEH 7 (PE)Dokument2 SeitenA Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in MAPEH 7 (PE)caloy bardzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lancru hzj105 DieselDokument2 SeitenLancru hzj105 DieselMuhammad MasdukiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Refutation EssayDokument6 SeitenRefutation Essayapi-314826327Noch keine Bewertungen

- LLM Letter Short LogoDokument1 SeiteLLM Letter Short LogoKidMonkey2299Noch keine Bewertungen

- Unbound DNS Server Tutorial at CalomelDokument25 SeitenUnbound DNS Server Tutorial at CalomelPradyumna Singh RathoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- UFO Yukon Spring 2010Dokument8 SeitenUFO Yukon Spring 2010Joy SimsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Enzymes IntroDokument33 SeitenEnzymes IntropragyasimsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artificial Intelligence Practical 1Dokument5 SeitenArtificial Intelligence Practical 1sadani1989Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ismb ItpDokument3 SeitenIsmb ItpKumar AbhishekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aero Ebook - Choosing The Design of Your Aircraft - Chris Heintz PDFDokument6 SeitenAero Ebook - Choosing The Design of Your Aircraft - Chris Heintz PDFGana tp100% (1)

- Verniers Micrometers and Measurement Uncertainty and Digital2Dokument30 SeitenVerniers Micrometers and Measurement Uncertainty and Digital2Raymond ScottNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beyond Models and Metaphors Complexity Theory, Systems Thinking and - Bousquet & CurtisDokument21 SeitenBeyond Models and Metaphors Complexity Theory, Systems Thinking and - Bousquet & CurtisEra B. LargisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angel C. Delos Santos: Personal DataDokument8 SeitenAngel C. Delos Santos: Personal DataAngel Cascayan Delos SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Comma Rules Conversion 15 SlidesDokument15 SeitenThe Comma Rules Conversion 15 SlidesToh Choon HongNoch keine Bewertungen