Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Beebe - Expectations, Perceptions, and Management of Labor in Nulliparas Prior To Hospitalization

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous bq4KY0mcWGOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Beebe - Expectations, Perceptions, and Management of Labor in Nulliparas Prior To Hospitalization

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous bq4KY0mcWGCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Expectations, Perceptions, and Management of Labor in

Nulliparas Prior to Hospitalization

Kathleen R. Beebe, RNC, PhD, and Janice Humphreys, RN, CS, PhD

This ethnographic qualitative study was designed to explore the phenomenon of prehospitalization labor from

the perspective of nulliparous women. Twenty-three women were interviewed in the early postpartum period

using a semistructured interview guide. The participants recounted their experiences with labor onset

recognition and management before being admitted to the hospital for birthing. Qualitative analyses included

verbatim transcription of audiotaped interviews, line-by-line coding, and categorization of data into codes

and categories. Interpretive analyses were validated with a collaborative research team and the participants

themselves. The central theme that emerged from this study was confronting the relative incongruence

between expectations and actual experiences. Supporting categories included: expectations about the labor

experience, identifying labor onset, managing the physical and emotional responses to labor, supportive

resources, and decision making about hospital admission. Early labor experiences in nulliparas offer insight

into the contributions of both expectations and environment to adaptation in labor. Midwives and perinatal

nurses are in a unique position to design interventions that support and reinforce laboring womens activities

outside of the hospital setting. J Midwifery Womens Health 2006;51:347353 2006 by the American

College of Nurse-Midwives.

keywords: adaptation, decision making, labor onset, life experiences, nulliparity, pregnant women,

sensation, pregnancy, qualitative research, symptom management

INTRODUCTION support the influence of environment on the biopsycho-

social aspects of the childbirth process2,3,1214 and on

Although 99% of births in the United States today occur

birth outcomes. Two recent studies that evaluated the

in a hospital,1 most women who experience spontaneous

benefits of delayed hospital admission on birth outcomes

labor onset do so outside of the hospital setting. Conse-

demonstrated that environment along with personal char-

quently, they spend various intervals of time laboring in

acteristics (such as parity) influences labor variables.2,3

other locales prior to hospital admission. Recent studies

Although these studies support the safety and efficacy of

support the benefits of postponing hospital admission

noninstitutionalized early labor in low-risk women, they

until active labor is established.2,3 However, because

did not explore the mechanisms by which women iden-

active labor is defined by a particular rate of cervical

tify, integrate, and manage this phenomenon.

dilation rather than by subjective behaviors, it is not

Many women plan for and idealize the awaited events

usually assessed in the home environment.4 Thus, labor-

of labor and birth, but they may not be fully prepared for

ing women, particularly those experiencing their first

the various decisions associated with early labor man-

births, must assume the tasks of recognizing the onset of

agement. A number of studies have evaluated the role of

true labor as well as determining the right time to

factors such as experience, expectations, ambivalence,

transfer to the hospital. Uncertainty and frustration can

and support in womens decision-making processes dur-

result when women enter the hospital only to be told that

ing childbirth.1518 Findings from these investigations

they are not really in labor. Other women, who may

confirm that laboring women are faced with a number of

have believed they were not coping well during labor at

decisions about childbearing preferences and that con-

home, learn they are in very advanced labor on hospital

textual factors play a role in the degree and quality of

admission. These experiences highlight the challenges

womens participation in these decisions. However, fur-

women face in interpreting and acting on somatic and

ther investigation is needed of womens experiences as

affective cues that labor has begun.

they enter labor for the first time, particularly the influ-

Published investigations of experiences during labor

ence of environment on such experiences. This qualita-

prior to hospital admission are scarce, particularly those

tive study explored the phenomenon of labor prior to

addressing womens perceptions of the labor environ-

hospital admission from the perspective of nulliparous

ment as a qualitative component of the birthing experi-

women.

ence. Numerous studies have addressed the physical and

psychological components of labor,511 but they have

METHODS

focused on hospitalized women. There is evidence to

This study was an ethnographic qualitative analysis of

data from women experiencing labor for the first time.

Data were largely derived from interviews conducted

Address correspondence to Kathleen R. Beebe, RNC, PhD, Dominican

University of California, 50 Acacia Ave., San Rafael, CA 94901. during a previous study of biopsychosocial influences on

E-mail: kbeebe@dominican.edu prehospitalization labor,19 supplemented by additional

Journal of Midwifery & Womens Health www.jmwh.org 347

2006 by the American College of Nurse-Midwives 1526-9523/06/$32.00 doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.02.013

Issued by Elsevier Inc.

data that were collected after development of this re- Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample (N 23)

search emphasis. Face-to-face, audiotaped interviews

were used to collect the data. Variable n (%)

Twenty-three women experiencing their first births, Age (y)

who were recruited through convenience sampling at 1825 7 (30.4)

childbirth preparation classes or on inpatient postpartum 2630 6 (26.1)

units. Nulliparas were selected as the population of 3135 7 (30.4)

3640 3 (13.1)

interest because this group has significantly longer labor

Ethnicity

durations than parous women20 22 and because the level Caucasian 20 (87)

of experience with childbirth is assumed to contribute to Hispanic 2 (8.7)

patterns of behavior during labor. Participants had un- Other 1 (4.3)

complicated, singleton, term pregnancies, and began Education

High school 3 (13)

spontaneous labor outside of the hospital. The women

Some college 7 (30.4)

were from two locations on the West Coast: one, a large College 8 (34.8)

city (n 4), and, a suburban/rural setting (n 19). All Some graduate school 2 (8.7)

were partnered, had participated in childbirth preparation Graduate degree 3 (13.1)

classes, and were planning hospital births. Nineteen Annual household income

$25,000 4 (17.4)

women had been interviewed for the original study,19

$25,000$50,000 5 (21.7)

which investigated associations among selected third- $50,000$100,000 11 (47.8)

trimester and early labor variables in nulliparas, and $100,000 1 (4.3)

included an elicited, semistructured narrative of the Unreported 2 (8.7)

prehospitalization labor experience. By using the same

format, four additional women were recruited and inter-

viewed as analysis proceeded to enhance the trustworthi-

included the two authors and two nurse researchers

ness of the findings. The additional participants were also

experienced in qualitative methods and perinatal phe-

used to validate the emerging themes from the initial

nomena. This process culminated in the emergence of a

cohort and to ensure sufficiency of data within the

central theme illuminating the interrelationships among

qualitative analytic process.

categories.

After securing written informed consent (with ap-

Analysis of these data was conducted with consider-

proval from the University of California, San Franciscos

ation for analytical precision and theoretical connected-

Institutional Review Board, Committee on Human Re-

ness.24 Trustworthiness of the findings was enhanced by

search), participants met for a 60- to 90-minute interview

validation with participants, sustained involvement in the

with the first author. A semistructured interview guide

field, and discussion with two nurse researchers experi-

was developed (Appendix A) and used to elicit partici-

enced in qualitative methods.

pants experiences and management strategies during

labor prior to hospital admission. Probes were used when

needed to further explore the processes of navigating RESULTS

prehospitalization labor. All interviews were audiotaped Table 1 lists the demographic characteristics of the entire

and transcribed verbatim. sample. The central theme that emerged during this

Analysis proceeded from an overall read of the inter- exploration of the phenomenon of prehospitalization

views followed by line-by-line coding. Categories labor for nulliparas was confronting the relative incon-

emerged from commonalities among the codes as the gruence between expectations and actual experiences.

analytic process produced higher levels of abstraction. This theme was evident within all of the identified

Key associations among words and clusters of phrases supporting categories, which included expectations,

were scrutinized for related components and used to identifying labor onset, managing the experience, sup-

structure analytic categories.23 These categories were portive resources, and decision making about going to

discussed and agreed on by the research team, which the hospital.

Expectations

Kathleen R. Beebe, RNC, PhD, is Assistant Professor of Nursing at

Dominican University of California in San Rafael, a former Post-Doctoral Because of inexperience with childbirth, many women

Fellow in the Center for Symptom Management at the University of sought information about what sensations to anticipate to

California, San Francisco, and a Staff Nurse in the Labor and Delivery Unit construct their idealized labor experience. Their expec-

at Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital, Santa Rosa, CA.

tations about birthing were derived from a number of

Janice Humphreys, RN, PhD, CS, PNP, is Associate Professor of Nursing

and Vice-Chair for Faculty Practice in the Department of Family Health sources, including vicarious experience; childbirth edu-

Care Nursing at the University of California, San Francisco. cation; discussions with others; prior experiences with

348 Volume 51, No. 5, September/October 2006

physically challenging or painful events, attitudes, and discussions with partners, inner dialogues, waiting, and

desires; and body cues. The expectations about labor monitoring signs and symptoms. Reappraising expecta-

centered on two main components: what it would be like tions about labor onset and modifying them accordingly

and how it would be managed. was part of the process of labor recognition.

I really did think that I was not in labor. I I thought it was just a bladder infection. On the

thought this is just one of those things, maybe its way to the doctor, everything hurts. . .and Im

a precursor. But, you know, being your first time, starting to go either Im in labor or Im not

you think labors gonna be this incredibly, all of . . .well, Im in labor but its not making any

a sudden, intense thing that you cant handle, and progress. I almost cried when he said I was six

when it comes on a little slower, you just, nah, centimeters dilated I was so happy. I was thinking

its not labor, I have something else. theyd tell me to get ready for a really long part of

labor.

Although there was variation in womens expectations

about what labor would be like and how it would be So I kind of told myself that, you know, this

managed, there were commonalities in the articulation of probably isnt it. . .I didnt really tell myself that

each distinct component. Expectations for managing thats probably what it was until later at night. . .I

labor were well defined and sometimes elaborate, indi- kind of suspected by the time I went to bed. . .I

cating an emphasis on the performance aspects of birth- was thinking, OK, this is probably it.

ing. However, the expectations about what labor would

feel like were more uncertain. Consequently, with actual Managing Symptoms and Emotional Responses

labor onset, both sets of expectations required reap- Participants described a host of physical sensations as

praisal, and often, modification. part of the prehospitalization labor experience (Table 2).

These sensations and an evaluation of their significance

Identifying LaborThe Real Thing produced individual patterns of responses designed to

Retrospectively, participants could describe with ease the manage them.

details about the beginning of labor. However, most Women experienced numerous emotions during this

participants recalled an uncertainty about labor onset as it time (Table 3). These were mercurial and sometimes

was happening. The phrase the real thing was used so contradictory (simultaneously happy and sad) but not

frequently in womens descriptions of querying labor without contextual meaning and rationale. Affective

onset that it became a category unto itself. The frequency responses were dynamic and influenced by the degree

of the use of the words real thing, really it?, and and duration of physical symptoms, interpersonal inter-

real demonstrates the immense importance assigned to actions, and the surrounding environment.

the task of properly diagnosing labor. As with the recognition of labor onset, the planned

Womens expectations about what labor would feel activities to manage prehospitalization labor were de-

like influenced their abilities to recognize labor onset. rived from expectations regarding perceived resources

Other factors linked to labor onset recognition included: and capabilities. These expectations were generated from

inexperience, ambivalence, concerns about bothering the information received during childbirth preparation

others, the desire to complete the pregnancy, concerns classes or other experienced and trusted sources.

about hospitalization, and other third-trimester symp- Women developed individualized plans of action us-

toms. The actual physical sensations associated with ing specific activities and props (items that supported

labor onset were overlooked, downplayed, or attributed the activities) that fit with their preconceived or learned

to other causes when they did not match pre-existing notions of what would be helpful to do during labor.

expectations about severity or location. In this group, for Somebody told me that when youre in labor,

example, labor was mistaken for a bladder infection, stomp. A couple of people told me that. . .try to get

constipation, overdoing it, or food poisoning. that head engaged.

Its interesting because the contractions (that) After labor onset, however, women very often found

were described to me in class, or the way I themselves rethinking the plan of action based on how

interpreted them, didnt feel the way I felt when they were feeling at the time.

I. . .it just felt more like cramps. I dont know, the

Subject: We had the aromatherapy, we had

two just didnt go together for me. They didnt feel

CDs, we had tennis balls for massage. . .

the way I was expecting them to.

Husband: But, like, she was so tired from the

Strategies to facilitate reconciliation between expecta- first two days, that I think if we brought it out it

tions and the actual event of labor onset included woulda just irritated her.

telephone calls to providers, family members and friends, Subject: Yeah.

Journal of Midwifery & Womens Health www.jmwh.org 349

Table 2. Analytic Taxonomy and Descriptive Words Used for the 5) attend to nutritional, hydration, or hygienic needs;

Physical Sensations Experienced During Prehospitalization 6) garner support and reassurance; 7) stimulate or

Labor retard uterine contractions; and 8) determine the cor-

rect time to relocate to the hospital. In some cases,

Category Descriptors specific activities differed in intended purpose. For

Pain Uterine contractions example, one woman might perform a housecleaning

Menstrual-like cramping chore to distract herself from contractions, whereas

Backache another might do the same activity to prepare the home

Stabbed in the back

for the new baby.

Body aches

Stomach cramps

Fatigue Lethargy

Weakness Supportive Resources

Low energy

Tiredness Women called on a number of supportive resources to

Not myself assist them in managing prehospitalization labor. The

Lazy central theme of incongruence between expectations and

Struggling to walk actual events again emerged as participants reflected on

Pressure Heaviness

Pelvic pressure

the significance of their available support systems. The

Restlessness Sleep loss most important and frequently cited sources of support

Up all night were husbands/domestic partners. As one woman put it,

Have to keep moving around I couldnt have done it without him. Some men were

Discomfort Uncomfortable actually able to diagnose labor or ruptured membranes

Dont feel good

Achy

for their partners. Their objectivity, in concert with

Dyspnea Cant breathe

Hunger Hungry

Wanted to eat

Gastrointestinal/Genitourinary Distress Diarrhea Table 3. Emotional Classifications and Constituents of

Constipation Prehospitalization Labor

Nausea/vomiting

Taste alteration Category Descriptors

Urinary frequency/urgency Anxiety Worried

Have to go all the time Scared

Ruptured membranes Gush of fluid Impatient

Well-being Tolerable contractions Eager

Liked the discomfort Uncertain

Resting/napping Stressed

Not that bad Dissociation Out of my body

Strange

Weird

In a haze

To accommodate to the realities of the labor experi- Not feeling myself

ence, women called on their repertoire of learned strat- Detached from others

egies, suggestions from others, and improvisational Ambivalence Uncertain

Trying to ignore it

skills. Bored

It was quite calm actually. . .it was just the Positive affect (general) Happy

Excited

mundane things; going through and cleaning the Relaxed

bathroom and putting the laundry in the washing Calm

machine and making sure it got to the dryer. . .it Mentally prepared

was just the everyday chores that took your mind In control

off things. Eager

Not worried or scared

Some ideas for managing labor had no identifiable Relief

genesis. As one participant stated, my body was just Negative affect (general) Miserable

Terrible

moving me around. Frustrated

A wide variety of management strategies were used Irritable

during this period. These strategies were intended to 1) Dying

promote physical and/or emotional comfort; 2) prepare Tearful/emotional

for hospitalization, birth, and the new infant; 3) pass Sad

End of my rope

the time; 4) ignore or distract oneself from sensations;

350 Volume 51, No. 5, September/October 2006

their familiarity with her pregnancy, allowed them to Decision Making About HospitalizationGoing In

translate her sensations more accurately.

The decision about when and why to go into the hospital

during labor was an important one for the women in this

I got out of bed, and then we realized I had study. Participants expressed some ambivalence about

water, and I couldnt figure out what that was their ultimate birthing environment, with some clearly

either. Of course, my husband put two and two more comfortable about the hospital setting and others

together and realized it was my water. . .I was uncomfortable. Others accepted the hospital transition as

clueless, you know? I went into the bathroom and a necessary activity but were not sure about the best time

Im like, theres this water leaking out of me, I to make such a transition. The perceived benefits of

wonder what this is? Hes like, HELLO! You hospitalization reported by participants included access

know? How many books have I read for the last 9 to professional personnel to take care of them, monitor-

months and its just so overwhelming what youre ing equipment, immediate assistance for unanticipated

about to go through. complications, additional labor support and company,

medical advice and resources, information about labor

Other supportive individuals included mothers, fa-

progress, and pain-relieving medications. Perceived dis-

thers, sisters, in-laws, friends, and doulas. They played

advantages to the hospital setting were focused on the

an integral role in aiding women in labor to determine lack of self-directed and lower-tech labor management,

labor onset, manage labor as it evolved, and decide about which included being stuck in bed or jailed (immo-

going to the hospital. Health care providers served as bilized), being hooked up (to monitors), having IVs,

remote sources of support, offering advice and direction and requiring drugs to stimulate labor. The stated benefit

about labor progress and hospital admission planning. of the home setting was that it was a familiar and

Three quarters of the participants entered labor during comfortable environment where women felt more in

the night. In these cases, expectations about the role of control of their activities. One subject stated, I think as

support persons sometimes conflicted with actual levels long as Im home, Im in control. For some reason, I felt

of participation. like I had less control when I was in the hospital. The

concerns about the home setting included the inability to

He was in the room but he was sleeping. [He get an adequate assessment of labor progress, leading to

was] waking up every 10 or 15 minutes to [hear concerns about having the baby at home or going in too

me] me moaning and groaning. But. . .its funny late to receive planned analgesia or anesthesia.

now when I tell people, they crack up, yeah, he Decision making about going to the hospital involved

was sleeping the whole time. But, like I said, he a number of factors and usually other people. Some

didnt know if it was gonna be the real thing and women followed a set of criteria (usually related to

if it was he wanted to get his rest [before going to contraction frequency or duration) given to them by their

the hospital]. So that wasnt very helpful at all. providers. Frequently, the decision was made after a

telephone consultation with their providers.

When more than one support person was involved An often-cited reason for delaying hospital admission

with the participant, the relative dominance of each was was the fear of going in too soon. This was a particular

the result of a complex fabric of negotiation, collabora- concern for women because, as stated:

tion, interaction, and assigned agency. The social rela-

tionship aspect of managing labor at home became an The only thing I worried about was going to the

important part of womens labor experiences. The par- hospital maybe too soon. You have that fear of

ticipants did not fully appreciate the potential conflicts getting there and. . .then having the doctor tell me

among support people or between support people and that I could come in tomorrow, and kind of going

themselves until they were manifest during labor. over him and making that decision [to go in

sooner], and worrying about it being wrong. . .I

There was a time my husband kept asking me, just thought it would be bad if we get there only to

well, dont you want to go to the hospital? My be told to go back home. It would be

sister was here, so I felt safe with her here too, discouraging.

and then my mother-in-law kept telling them she For the few women who did go in for a labor

will know when its time to go to the hospital. evaluation and returned home undelivered, the thought of

They were all supportive of me being here. I think repeating that pattern was even more distressing.

that helped me relax being here and knowing I

was doing the right thing. . .but (my husband) Hes [husband] the one that said, We need to

being nervous made me kind of questionI call the doctor. Im not calling her; she thinks

wonder if I should go? Im a wimp. I dont want to go back. . . I dont

Journal of Midwifery & Womens Health www.jmwh.org 351

want to call her. I dont even want to bring my a richer description of the experiences and activities

bag. Its like shes going to send me home again. during labor prior to hospital admission than has

previously been reported. Women experiencing labor

The women who did have a formal labor evaluation

onset for the first time place a great deal of emphasis

sometime before hospital admission entered the hospital

on their performance. This is evidenced by the need to

for delivery, on average, much later in their labors than

prepare for and engage in the birthing process pro-

the rest of the sample. Many participants offered that if

ceeding from a preconceived, albeit sometimes unre-

they had known what their progress in labor had been in

alistic, set of expectations. The relative fit between

terms of cervical dilation and fetal well-being, they

these expectations and the actual sensations, behav-

would have stayed home longer before entering the

iors, and events women encounter contributes to the

hospital. Women who planned to stay out of the hospital

work of labor. Reappraisal and modifications of ex-

as long as possible before admission also found them-

pectations and planned activities are additional tasks

selves in need of feedback about labor progress.

in the early labor experience of first-time mothers.

So when I did hear that I was 7 centimeters, I Confronting and then realigning incongruences in

was very relieved. . .if Id known that at home, I these areas have been unrecognized factors that affect

probably wouldve. . .I mean, thats why I was adaptation and decision making within the labor pro-

getting scared. Cuz it was like if theyre not cess. The central theme of this study suggests that

timing these and theyre gonna make me stay at opportunities exist to assist nulliparous patients, be-

home because I said I want this natural childbirth fore and during labor, to narrow the gaps between

and I gotta stay at home for another 3 to 4 hours expectations about labor experiences and actual occur-

like this?. . .Im not gonna make it. rences.

A recent finding from the literature on decision

Although some participants considered homebirth,

making indicates that people wait to make important

none chose this option, primarily related to apprehension

decisions until they have acquired all of the relevant

about unavailability of neonatal services. Most did not

information needed to proceed.25 Participants in this

comment on the trip to the hospital, but a few reported an

study reported that, at times, they were unable to make

uncomfortable ride, feeling the lurching and bumping of

a decision about whether labor had begun or when the

the vehicle on top of the labor contractions.

best time to transfer to the hospital should be. In such

cases, confusion about their status resulted in difficulty

DISCUSSION

recognizing labor onset or progress and a perception

These findings, presented in a linear fashion, should that they may have been admitted to the hospital too

not be construed as occurring chronologically, but soon. Such perceptions can undermine confidence and

rather, as interwoven processes. It was not unusual for satisfaction with decision-making abilities. Midwives

participants to recount their use of management tech- and perinatal nurses are well-positioned to provide

niques for labor while still questioning whether labor information about progress in labor, reassurance about

had actually started. The identified categories repre- fetal well-being, and confirmation of the normalcy of

sent an interpretive evaluation of the experience of the birthing process as it is unfolding. These interven-

labor in nulliparas prior to hospital admission within a tions, along with supportive reassurance and reinforce-

particular demographic composition. Study limitations ment of coping strategies and symptom management

include the possibility of recall bias and a sample that activities in the early stages of labor are resources that

was fairly homogenous and not necessarily represen- can be safely and beneficially provided outside of the

tative of all nulliparous women. Future studies might hospital setting.2 Possible models of care might in-

focus on women with different demographic charac- clude home visitation or centralized outpatient facili-

teristics. ties for noninvasive early labor assessment and sup-

The notion that early labor is a light-hearted precur- port. Such approaches can assist women by facilitating

sor to the real work of active labor and delivery reconciliation of incongruences among expectations

negates the complexities of the mind-body recognition about labor and its realities. Further benefits may

of and adaptation to the birthing process. The fact that include reduced anxiety and uncertainty, along with

this crucial undertaking begins outside of the hospital improved confidence in decision-making abilities. Ul-

setting should not minimize its significance within the timately, better support for laboring women at home

continuum of childbirth. Environment is recognized as can contribute to overall improved labor progress and

an important domain of influence on human perception outcomes. The next step in this effort involves assess-

and interaction. It is precisely because labor onset ing the feasibility of establishing effective programs to

occurs away from the hospital and is experienced by provide such services, with the goal of promoting

women in unique contexts that environmental influ- labor care in an appropriate and comfortable environ-

ences must be appreciated. The current study provides ment.

352 Volume 51, No. 5, September/October 2006

This research was supported by the Nursing Research Training Program in childbirth: A randomized controlled trial of a decision-aid for

Symptom Management; awarded to the School of Nursing at the University informed birth after cesarean. Birth 2005;32:252 61.

of California, San Francisco, from the National Institute of Nursing 18. Hodnett ED. Pain and womens satisfaction with the expe-

Research (T32 NR07088). rience of childbirth: A systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2002;186(5 Suppl Nature):S160 72.

REFERENCES 19. Beebe KR. The influence of biopsychosocial characteristics

in the late third trimester on pre-hospitalization labor in nulliparas.

1. Curtin SC, Park MM. Trends in the attendant, place, and Ann Arbor (MI): UMI Dissertation Services, 2002.

timing of births, and in the use of obstetric interventions: United

States, 1989 97. Natl Vital Stat Rep 1999;47:112. 20. Friedman EA. Primigravid labor: A graphicostatistical anal-

ysis. Obstet Gynecol 1955;6:567 89.

2. McNiven PS, Williams JI, Hodnett E, et al. An early labor

assessment program: A randomized, controlled trial. Birth 1998; 21. Friedman EA, Sachtleben MR. Dysfunctional labor. Prolonged

25:510. latent phase in the nullipara. Obstet Gynecol 1961;17:135 48.

3. Jackson DJ, Lang JM, Ecker J, et al. Impact of collaborative 22. Friedman EA. Labor: Clinical evaluation and management.

management and early admission in labor on method of delivery. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1978.

J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2003;32:14757; discussion 58

23. Spradley J. The ethnographic interview. Belmont: Wads-

60.

worth Group/Thompson Learning, 1979.

4. Lauzon L, Hodnett E. Antenatal education for self-diagnosis

24. Cesario S, Morin K, Santa-Donato A. Evaluating the level of

of the onset of active labour at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

evidence of qualitative research. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs

2000;2:CD000935.

2002;31:708 14.

5. Ryding EL, Wijma B, Wijma K, Rydhstrom H. Fear of

25. Tykocinski OE, Ruffle BJ. Reasonable reasons for waiting. J

childbirth during pregnancy may increase the risk of emergency

Behav Decision-making 2003;16:4757.

cesarean section. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1998;77:5427.

6. Lederman RP, Lederman E, Work Jr, BA McCann DS. The

relationship of maternal anxiety, plasma catecholamines, and Appendix A. Interview Guide

plasma cortisol to progress in labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1978;

132:495500. This interview guide provided general guidelines for all

interviews. Further questioning built upon the subjects

7. Crowe K, von Baeyer C. Predictors of a positive childbirth responses.

experience. Birth 1989;16:59 63.

Environmental and Temporal Conditions

8. Wuitchik M, Hesson K, Bakal DA. Perinatal predictors of

pain and distress during labor. Birth 1990;17:186 91. 1. When did your labor begin? Where were you and how

9. Niven CA, Gijsbers K. Coping with labor pain. J Pain did you decide labor had started? Tell me about that.

Symptom Manage 1996;11:116 25. 2. How long were you in labor before you went into the

hospital?

10. Waldenstrom U. Experience of labor and birth in 1111

women. J Psychosom Res 1999;47:471 82. Thoughts, Feelings, Activities, and Experiences

11. Manning MM, Wright TL. Self-efficacy expectancies, out- 1. What did you do during the time you were in labor

come expectancies, and the persistence of pain control in child- before you went to the hospital?

birth. J Pers Soc Psychol 1983;45:42131.

2. What did you think about during the time you were in

12. Hodnett ED, Abel SM. Person-environment interaction as a labor before you went into the hospital?

determinant of labor length variables. Health Care Women Int 3. How did you feel during this time?

1986;7:34156. 4. Of the things you mentioned doing and thinking, what

13. Morse JM, Park C. Home birth and hospital deliveries: A was most helpful for you? Least helpful?

comparison of the perceived painfulness of parturition. Res Nurs 5. Do you recall where you learned to do these things?

Health 1988;11:175 81.

Transition to the Hospital

14. Cunningham JD. Experiences of Australian mothers who

gave birth either at home, at a birth centre, or in hospital labour 1. What made you decide to go to the hospital when you

wards. Soc Sci Med 1993;36:475 83. did? Were there any other deciding factors?

15. Carlton T, Callister LC, Stoneman E. Decision making in 2. Was it different being at home compared to being at

laboring women: Ethical issues for perinatal nurses. J Perinat the hospital during labor? If so, how?

Neonatal Nurs 2005;19:14554.

Probes for the interviewer

16. Fenwick J, Hauck Y, Downie J, Butt J. The childbirth Is there anything else you think is important for me to

expectations of a self-selected cohort of Western Australian know?

women. Midwifery 2005;21:2335. Tell me more about that.

17. Shorten A, Shorten B, Keogh J, et al. Making choices for Encourage examples/illustrations

Journal of Midwifery & Womens Health www.jmwh.org 353

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Special Report: Vitamins and MineralsDokument8 SeitenSpecial Report: Vitamins and MineralsAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Get ShreddedDokument17 SeitenGet ShreddedSlevin_KNoch keine Bewertungen

- PSMDokument62 SeitenPSMzamijakaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Addenbrookes Hospital Level 2 Floor PlanDokument1 SeiteAddenbrookes Hospital Level 2 Floor PlanMidiangr0% (1)

- Kennedy-Model of Exemplary Midwifery PracticeDokument16 SeitenKennedy-Model of Exemplary Midwifery PracticeAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group B Strep and Pregnancy: Frequently Asked Questions FAQ105 PregnancyDokument3 SeitenGroup B Strep and Pregnancy: Frequently Asked Questions FAQ105 PregnancyAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

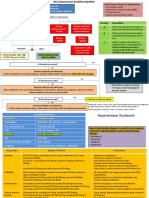

- JNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionDokument2 SeitenJNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- WHNP CoalitionDokument1 SeiteWHNP CoalitionAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wet Mount Proficiency 2008A Critique2Dokument4 SeitenWet Mount Proficiency 2008A Critique2Anonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- WHNP Research PrioritiesDokument18 SeitenWHNP Research PrioritiesAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wet Mount Proficiency Test 2007A CritiqueDokument6 SeitenWet Mount Proficiency Test 2007A CritiqueAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Suture Types PDFDokument2 SeitenSuture Types PDFAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- LOC Certificate For 'Assessing COPD in Primary Care - 0.5 Credit PDFDokument1 SeiteLOC Certificate For 'Assessing COPD in Primary Care - 0.5 Credit PDFAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- King & Pinger, Pearls of Midwifery PDFDokument14 SeitenKing & Pinger, Pearls of Midwifery PDFAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greulich - The Latent Phase of Labor-Diagnosis and ManagementDokument9 SeitenGreulich - The Latent Phase of Labor-Diagnosis and ManagementAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shingles - Patient Information PDFDokument4 SeitenShingles - Patient Information PDFAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1990-Fleming Suturing Method and PainDokument7 Seiten1990-Fleming Suturing Method and PainAnonymous bq4KY0mcWG0% (1)

- Erwin-Demystifying The Nurse-Midwifery MGMT Process 1987Dokument7 SeitenErwin-Demystifying The Nurse-Midwifery MGMT Process 1987Anonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shingles - Patient Information PDFDokument4 SeitenShingles - Patient Information PDFAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Healthy Menopause: Diet, Nutrition and Lifestyle GuidanceDokument8 SeitenA Healthy Menopause: Diet, Nutrition and Lifestyle GuidanceAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wellness Nutritionforwomenslides PDFDokument16 SeitenWellness Nutritionforwomenslides PDFAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Healthy Menopause: Diet, Nutrition and Lifestyle GuidanceDokument8 SeitenA Healthy Menopause: Diet, Nutrition and Lifestyle GuidanceAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2017 JNC 8 Lipid and HTN GuidelinesDokument28 Seiten2017 JNC 8 Lipid and HTN GuidelinesAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wellness Nutritionforwomenslides PDFDokument16 SeitenWellness Nutritionforwomenslides PDFAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Pearls and Memory Aids for PediatriciansDokument26 SeitenClinical Pearls and Memory Aids for PediatriciansAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Maintenance PostmenopauseDokument9 SeitenHealth Maintenance PostmenopauseAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lisinopri - CHF Dose Conversion For ARBsDokument1 SeiteLisinopri - CHF Dose Conversion For ARBsAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fetal DevelopmentDokument4 SeitenFetal DevelopmentAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statin Drug Interaction Pocket GuideDokument6 SeitenStatin Drug Interaction Pocket GuideAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Drug InteractionsDokument5 SeitenCritical Drug InteractionsAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1APHA2012HVNAslide2012 10 23handoutDokument34 Seiten1APHA2012HVNAslide2012 10 23handoutAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- HP1Dokument5 SeitenHP1Qusay AliraqiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rhetorical Analysis Revision Final ProjectDokument13 SeitenRhetorical Analysis Revision Final Projectapi-371084574100% (1)

- SPECIAL WORKSHOP ANNOUNCEMENT-with Keshe NotesDokument4 SeitenSPECIAL WORKSHOP ANNOUNCEMENT-with Keshe NotesAhmad AriesandyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Exam Budding ScientistsDokument3 Seiten2 Exam Budding ScientistsWassila Nour100% (1)

- Advances in Rapid Detection Methods For Foodborne PathogensDokument16 SeitenAdvances in Rapid Detection Methods For Foodborne PathogensƠi XờiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peace Corps Violation of Office of Victim Advocate Clearances by OVA Employee DI-16-0254 WB CommentsDokument26 SeitenPeace Corps Violation of Office of Victim Advocate Clearances by OVA Employee DI-16-0254 WB CommentsAccessible Journal Media: Peace Corps DocumentsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ujjwala Saga PDFDokument84 SeitenUjjwala Saga PDFRishi ModiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kegawatdaruratan Bidang Ilmu Penyakit Dalam: I.Penyakit Dalam - MIC/ICU FK - UNPAD - RS DR - Hasan Sadikin BandungDokument47 SeitenKegawatdaruratan Bidang Ilmu Penyakit Dalam: I.Penyakit Dalam - MIC/ICU FK - UNPAD - RS DR - Hasan Sadikin BandungEfa FathurohmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digestive System Parts PacketDokument2 SeitenDigestive System Parts PacketRusherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nilai GiziDokument3 SeitenNilai GiziDwi Rendiani SeptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Good Will Hunting Report AnalysisDokument8 SeitenGood Will Hunting Report AnalysislylavanesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpretation: L23 - FPSC Malviya Nagar1 A-88 Shivanand Marg, Malviyanagar JaipurDokument4 SeitenInterpretation: L23 - FPSC Malviya Nagar1 A-88 Shivanand Marg, Malviyanagar Jaipurmahima goyalNoch keine Bewertungen

- DSMDokument2 SeitenDSMOtilia EmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Efects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in Children and Young People With Psychiatric Disorders - A Systematic ReviewDokument21 SeitenEfects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in Children and Young People With Psychiatric Disorders - A Systematic ReviewSarwar BaigNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Cleaner Production: Waqas Nawaz, Muammer KoçDokument20 SeitenJournal of Cleaner Production: Waqas Nawaz, Muammer Koçthe unkownNoch keine Bewertungen

- 119 Concept PaperDokument4 Seiten119 Concept PaperBern NerquitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name: Jaanvi Mahajan Course: 2ballb Hons. REGISTRATION NO.: 22212033 Subject: Law and Medicine Submitted To: Mrs. Vijaishree Dubey PandeyDokument9 SeitenName: Jaanvi Mahajan Course: 2ballb Hons. REGISTRATION NO.: 22212033 Subject: Law and Medicine Submitted To: Mrs. Vijaishree Dubey Pandeyjaanvi mahajanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Physical Fitness TestDokument8 SeitenPhysical Fitness Testalaskador03Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0738399110003150 Main PDFDokument5 Seiten1 s2.0 S0738399110003150 Main PDFkhai2646Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bakteri Anaerob: Morfologi, Fisiologi, Epidemiologi, Diagnosis, Pemeriksaan Sy. Miftahul El J.TDokument46 SeitenBakteri Anaerob: Morfologi, Fisiologi, Epidemiologi, Diagnosis, Pemeriksaan Sy. Miftahul El J.TAlif NakyukoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isak 1 2 ViennaDokument6 SeitenIsak 1 2 Viennanifej15595Noch keine Bewertungen

- Eco-Friendly Fitness: 'Plogging' Sweeps the GlobeDokument2 SeitenEco-Friendly Fitness: 'Plogging' Sweeps the GlobecarlosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Relevance of Root Canal Isthmuses in Endodontic RehabilitationDokument13 SeitenThe Relevance of Root Canal Isthmuses in Endodontic RehabilitationVictorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Fats in Periodontal DiseaseDokument9 SeitenRole of Fats in Periodontal DiseaseandrealezamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ca LidahDokument27 SeitenCa LidahArnaz AdisaputraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Children's Congress ProposalDokument5 SeitenChildren's Congress ProposalMA. CRISTINA SERVANDONoch keine Bewertungen

- AVJ Ablation Vs CardioversionDokument6 SeitenAVJ Ablation Vs CardioversionAndy CordekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study 1 Barry and Communication BarDokument3 SeitenCase Study 1 Barry and Communication BarNishkarsh ThakurNoch keine Bewertungen