Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Should Conservatives Abandon Textual Criticism

Hochgeladen von

Adriano Da Silva CarvalhoCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Should Conservatives Abandon Textual Criticism

Hochgeladen von

Adriano Da Silva CarvalhoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Should Conservatives Abandon

Textual Criticism?

Marchant A. King

After the lapse of nearly a century there has again arisen, par-

ticularly among strong conservative groups, a call to repudiate the

results of the textual studies pursued since the middle of last century

and accept the Textus Receptus as the authoritative text of the New

Testament. Allied with the acceptance of the Textus Receptus as

the authoritative text is the claim that the King James Version is the

preferred translation of the Greek Text. The full conservative who

does not wish so to repudiate textual studies does not question the

beauty, suitability, or usefulness of the King James Version. Its

cadence, balance, and propriety of expression are superb, and its

suitability for use in worship or in general is not questioned. The

question is simply whether we are to abandon the work of such

men as Tischendorf, Westcott and Hort, and Nestle and assert that

the Textus Receptus represents in an unquestionable way the original

reading of the New Testament.

T H E GENERAL ARGUMENTS OF THE

TEXTUS RECEPTUS PROPONENTS

First, the claim that modern textual criticism is rationalistic and

has no regard for the special character of the Bible. This may well

be true of some writers in this field but certainly is not true of many.

Among the outstanding early ones Tischendorf was a very godly man,

Westcott has given us some of our finest and most conservative com-

mentaries, and Tregelles was a solid evangelical, while in more recent

days A. T. Robertson, J. Gresham Machen, and Henry Thiessen were

35

36 / Bibliotheca Sacra January 1973

fully convinced of the validity of textual criticism and they are hardly

to be accused of disloyalty to the Bible.

Second, the claim that we must believe God has kept the true

text the possession of His people through the centuries. However

desirable it might seem for us to be sure that the text to which we

are accustomed is the true one we must face the facts. The Textus Re-

ceptus was not the text of the early church in Egypt, nor was it so

in Palestine. The Caesarean type of Greek text certainly existed early

and seems to have been fairly wide-spread, and the somewhat later

Palestinian Syriac was quite close to the Alexandrian. Neither was

the Textus Receptus the text of the Western church. The Old Latin

obviously was not based on it and when Jerome, probably the ablest

literary man in the early Western church, was preparing to do his

New Testament translation, he studied the available Greek manu-

scripts and selected what he thought were the best. The result is that

the Vulgate is very much closer in text to the Alexandrian (and the

present critical text) than it is to the Textus Receptus, and the Vulgate

became the Bible of Western Christians who certainly had as valid a

claim to being God's people as those of Constantinople. The Textus

Receptus, then, has no exclusive right to be considered the text that

God kept as the possession of His people in early days.

Furthermore, we can hardly argue that God must have kept the

true text the possession of His people, for He actually allowed the

church generally to lose some things that are a great deal more im-

portant than the difference between the critical text and the Textus

Receptus. He allowed the church to lose, for 1000 years and more,

(the Byzantine church to this day!) justification by faith, union with

Christ, the spiritual nature of the church, the priesthood of all be-

lievers, and gradually the Bible itself as far as the common people

were concerned.

SOME OF THE SPECIFIC ARGUMENTS

First, opposition to the value of older manuscripts. It certainly

is true that age alone does not guarantee value, but it is just as true

that, other things being equal, the manuscript least removed from the

autograph has the greatest likelihood of similarity to it. Furthermore,

age is among the least subjective elements in manuscript evaluation.

Professor Hodges, however, notes that our early manuscripts are all

from Egypt and urges that there is no good reason to think they

Should Conservatives Abandon Textual Criticism? / 37

are samples of the rest.1 One might, with no poorer factual basis, ask

what good reason there is to think they are not. The early Egyptian

church certainly gives every evidence of loyalty to the Scriptures.

But the actual fact is that these manuscripts are the only really early

ones we have, and we have them for no other reason, from the

natural standpoint, than the dryness of Egypt.

When we do begin to get manuscripts from other areas they

certainly are not like the Textus Receptus. The Old Latin manu-

script a is from the fourth century, k (with considerable Alexandrian

influence) fourth or fifth century, and Bezae and ten others from the

fifth century, and all these are from the West, not from Egypt and

not at all like the Textus Receptus. Also the Sinaitic and Curetonian

manuscripts of the Old Syriac from the fourth and fifth centuries

are not from Egypt, yet they do not show a Textus Receptus type

of text. So even at the time the Byzantine type text was appearing

in Egypt it seems not to have penetrated the West or as yet the

Syriac-speaking East.

Second, Professor Hodges quite correctly points out that West-

cott and Hort were wrong in their assertion that the Byzantine text

resulted from a specific revision, that no Byzantine readings appeared

until late third century.2 Actually there are a number of Byzantine-

type reading in P 66 which is dated about 200. However, the gradual-

ness of the process of adopting these smoother-type readings in

areas like Egypt does not increase their authenticity. That the By-

zantine scribes had great influence in the Eastern Church seems

demonstrated by the fact that in P 72 dated late third or fourth cen-

tury, the text of 1 Peter shows considerable elements of the

Byzantine, while 2 Peter, accepted and used in Egypt but not in Con-

stantinople, has virtually no Byzantine elements.

Professor Hodges urges that the uniformity of the many Byzan-

tine manuscripts can only be accounted for by their having come from

the autograph by direct line.3 But might not the appeal of the

smoother reading and the explanatory phrase be an equally possible

cause? While there is agreement on these smoother readings, the

fact is that there are also differences in the text of the manuscripts,

and to such an extent that Colwell has identified "families" among

1 Zane C. Hodges, "The Greek Text of the King James Version," Which

Bible? ed. by David Otis Fuller (2nd ed.; Grand Rapids, 1971), p. 28.

2 Ibid., p. 32.

3 Ibid., p. 34.

38 / Bibliotheca Sacra January 1973

these very cursives that are claimed to be uniform because they came

from the autograph by direct line. An important and easily verified

example would be Acts 20:28. But the lack of consensus among the

cursives in Revelation is, of course, the most extensive example.

Third, the claim that modern textual criticism is basically sub-

jective. This may well be true of some who advance an "eclectic text,"

but certainly it is not true of a real conservative whose whole aim is

to apply the objective standards in as honest a way as possible. He is

happy when Romans 8:1 is ended at "in Christ Jesus," but he is just

as insistent on the omission of Acts 8:37, however precious to him is

the confession of the deity of Christ.

Fourth, the claim that the extant, early manuscripts survived

because they were rejected "as faulty and so not used/'4 This is thor-

oughly answered by the fact that we have the notations on the margins

and between the lines of the early manuscripts made by various scribes

who over the years studied and worked on them. P 66 and P 75 from

about 200 have such notations and so do the later papyri. Vaticanus

has the notations of at least two such "correctors," one from shortly

after its writing and the other later. Sinaiticus has evidence of seven

distinguishable hands that worked over it and the same marks of

intensive use are seen in the others. Then there are more novel proofs

of use. P 75 was for a time so available in a home that a child once

(and only once!) used it as a "workbook," copying a part of the top

line of the page in large, sprawling letters along the top margin and

manuscript a, considered the earliest of the extant Old Latin, has,

according to Souter, "suffered much more from the kisses of wor-

shipers throughout the centuries."

THE EMPHASIS OF THE TRINITARIAN BIBLE SOCIETY

This group is urging a repudiation of the results of textual criti-

cism along with the Revised Standard Version as having deleted or

played down the deity of Christ. This to a conservative is a very

serious charge and would seem to be true of the Revised Standard

Version in some instances. Its translation of Romans 9:5 appears to

be a conscious avoidance of a clear reference to the deity of Christ,

and in Acts 20:28 it has departed from Vaticanus and Sinaiticus and

so does not have this assertion of His deity.

4 David Otis Fuller, "Why This Book?" Which Bible? ed. by David Otis

Fuller (2nd ed.; Grand Rapids, 1971), p. 7.

Should Conservatives Abandon Textual Criticism? / 39

The question, however, which chiefly concerns one at this time

is whether textual criticism is guilty of this action and one may im-

mediately say that, except for unbelievers who might get into this

field, there is no intention to do so. A Tregelles or a Machen hardly

intended to play down the deity of Christ any more than did Atha-

nasius, the most consistent known user in ancient days of the text

type preferred by present textual criticism. It is true that the critical

text omits Acts 8:37 but so do not only the early papyri, the early

uncials, the lectionaries, the Syriac, and the Egyptian, but the Byzan-

tine cursives themselves, the very group of manuscripts these men

professedly are following! In John 1:18 the great Alexandrian uncials

along with the A.D. 200 papyri read "God" rather than "Son" of

the Textus Receptus. Certainly "only begotten God" is more difficult

than "only begotten Son" (Is one ready to desert the principle that

scribes tended to go to the more easily understood?), but one thing

is sure, "only begotten God" does not play down the deity of Christ.

Again in Acts 20:28 the Alexandrian reads "God" in reference to

Christ while some of the Byzantine read "Lord," a good many have

"Lord and God," and most of the rest have "the Lord God." Here

again the Alexandrian reading is clearer on Christ's deity than the

various Byzantine readings. On 2 Peter 1:1 the Trinitarian Bible

Society seems confused. There is no question on the Greek text, and

even the Revised Standard Version gives the correct translation "our

God and Savior Jesus Christ" while the Authorized Version has "the

righteousness of God and our Saviour." (The clarity on Christ's deity

in this passage probably does not annoy the liberal since he rejects

the apostolicity of 2 Peter.)

The full conservative who accepts the principles of textual

criticism is impressed also by considerations such as these.

First, the conclusions of the earlier workers in textual criticism

have been amply confirmed by recent manuscript discoveries. The

papyri that are early are strongly Alexandrian. The three major ones

(about 200), P46' 66> 75, are decidedly Alexandrian and the oldest

known New Testament manuscript, the Rylands fragment, from about

A.D. 125, while containing only one point at which variations occur,

has at that point exactly the Alexandrian reading. This manuscript

evidently was made only a relatively few years after the Gospel of

John was written.

Second, textual criticism has cleared Romans 8:1 from the pos-

sible implication of works religion in the Textus Receptus reading.

40 / Bibliotheca Sacra January 1973

Every early manuscript known ends the statement with "Christ Jesus"

and the "correctors' " notes on Claromontanus (sixth century) give

something of a history of the text at this point. The original hand, as

just indicated, ended the verse with "Christ Jesus." Some time later a

"corrector" added in the margin "who walk not after the flesh" and

still later on another added "but after the Spirit."

Third, to issue a New Testament that follows the Textus Recep-

tus without explanation on passages such as 1 John 5:7 or the

account of the woman taken in adultery seems to be quite misleading.

The latter is not found in any early manuscript except the Western

family, nor is it included in a fair number of later ones. The great

early papyri of John, even though showing the work of correctors

through this part of the Gospel, do not have the slightest hint of there

being anything omitted here. Furthermore this passage is placed in

various other locations in the gospels. The family of later manuscripts

designated /l and some manuscripts of the Armenian version place it

after John 21:24. Another prominent group place the passage fol-

lowing Luke 21:38. Cursive 225 puts it after John 7:36 and about

a dozen manuscripts put an asterisk or similar warning mark on the

passage. Phenomena like these seem inexplicable if the passage was

a part of John's original writing. As for 1 John 5:7, this verse is

not found in the Byzantine manuscripts themselves. In fact, it is not

found in any Greek manuscript, of any age, yet it is included in the

Textus Receptus!

Finally, that God has graciously allowed the great early uncials

like Vaticanus to be made available for scholarly use as well as the

recent discovery of the very early papyri, particularly of John, would

seem to call for fervent thanksgiving to the Lord and reverent atten-

tion to their testimony rather than opposition.

^ s

Copyright and Use:

As an ATLAS user, you may print, download, or send articles for individual use

according to fair use as defined by U.S. and international copyright law and as

otherwise authorized under your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement.

No content may be copied or emailed to multiple sites or publicly posted without the

copyright holder(s)' express written permission. Any use, decompiling,

reproduction, or distribution of this journal in excess of fair use provisions may be a

violation of copyright law.

This journal is made available to you through the ATLAS collection with permission

from the copyright holder(s). The copyright holder for an entire issue of a journal

typically is the journal owner, who also may own the copyright in each article. However,

for certain articles, the author of the article may maintain the copyright in the article.

Please contact the copyright holder(s) to request permission to use an article or specific

work for any use not covered by the fair use provisions of the copyright laws or covered

by your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement. For information regarding the

copyright holder(s), please refer to the copyright information in the journal, if available,

or contact ATLA to request contact information for the copyright holder(s).

About ATLAS:

The ATLA Serials (ATLAS) collection contains electronic versions of previously

published religion and theology journals reproduced with permission. The ATLAS

collection is owned and managed by the American Theological Library Association

(ATLA) and received initial funding from Lilly Endowment Inc.

The design and final form of this electronic document is the property of the American

Theological Library Association.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Bible and Abortion: Exodus 21:22-23 in The Septuagint and Other OpinionsDokument5 SeitenThe Bible and Abortion: Exodus 21:22-23 in The Septuagint and Other OpinionsAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Verdadeira Origem Da Páscoa PDFDokument23 SeitenA Verdadeira Origem Da Páscoa PDFAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epicurus Voor Ho Eve Final Sept 152018Dokument22 SeitenEpicurus Voor Ho Eve Final Sept 152018Espinas SabrinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delphi As A World Cultural Place: Sustainable Development, Culture, Traditions Journal January 2013Dokument9 SeitenDelphi As A World Cultural Place: Sustainable Development, Culture, Traditions Journal January 2013Adriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 44 2 PP253 270 - Jets PDFDokument17 Seiten44 2 PP253 270 - Jets PDF321876Noch keine Bewertungen

- On Authorial Intention - HirschDokument21 SeitenOn Authorial Intention - HirschAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baruch Spinoza and The Naturalisation of The Bible: An Epistemological InvestigationDokument9 SeitenBaruch Spinoza and The Naturalisation of The Bible: An Epistemological InvestigationAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Luckenbill, D. D.) Ancient Records of Assyria and PDFDokument313 Seiten(Luckenbill, D. D.) Ancient Records of Assyria and PDFAlireza EsfandiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modern Textual Criticism and The Majority Text A ResponseDokument14 SeitenModern Textual Criticism and The Majority Text A ResponseAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lutheranism and The Inerrancy of ScriptureDokument14 SeitenLutheranism and The Inerrancy of ScriptureAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Origen and The Inerrancy of Scripture PDFDokument12 SeitenOrigen and The Inerrancy of Scripture PDFAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sexualidade e ReligiãoDokument15 SeitenSexualidade e ReligiãoAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criticism of The New Testament (1902) Various AuthorsDokument250 SeitenCriticism of The New Testament (1902) Various AuthorsDavid BaileyNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Textual Criticism Can Help HistoriansDokument24 SeitenHow Textual Criticism Can Help HistoriansAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bible Greek Vpod PDFDokument134 SeitenBible Greek Vpod PDFAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Persistent Problems Confronting Bible Translators Bruce M. Metzger PDFDokument13 SeitenPersistent Problems Confronting Bible Translators Bruce M. Metzger PDFAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lyotard-The Postmodern Condition A PDFDokument68 SeitenLyotard-The Postmodern Condition A PDFLev Lafayette88% (8)

- Can We Risk Another Textus ReceptusDokument6 SeitenCan We Risk Another Textus ReceptusAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Evaluation of The Bible Societies Tex of Greek New TesaDokument4 SeitenAn Evaluation of The Bible Societies Tex of Greek New TesaAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Methodological Dilemma of Evaluating Social History and Scribal HabitsDokument19 SeitenThe Methodological Dilemma of Evaluating Social History and Scribal HabitsAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Text of The New Testament Jack P LewisDokument11 SeitenThe Text of The New Testament Jack P LewisAdriano Da Silva Carvalho100% (1)

- Should Conservatives Abandon Textual CriticismDokument7 SeitenShould Conservatives Abandon Textual CriticismAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inductivism Inerrancy and PresuppositionalismDokument18 SeitenInductivism Inerrancy and PresuppositionalismAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Methodological Dilemma of Evaluating Social History and Scribal HabitsDokument19 SeitenThe Methodological Dilemma of Evaluating Social History and Scribal HabitsAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Persistent Problems Confronting Bible Translators Bruce M. Metzger PDFDokument13 SeitenPersistent Problems Confronting Bible Translators Bruce M. Metzger PDFAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Citation of Manuscripts in Recent Printed Editions of The Greek New Testament PDFDokument37 SeitenThe Citation of Manuscripts in Recent Printed Editions of The Greek New Testament PDFAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Transcriptional Debate On Mark 1-1Dokument15 SeitenThe Role of Transcriptional Debate On Mark 1-1Adriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Citation of Manuscripts in Recent Printed Editions of The Greek New TestamentDokument37 SeitenThe Citation of Manuscripts in Recent Printed Editions of The Greek New TestamentAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reabilitação Textual Do Novo TestamentoDokument48 SeitenReabilitação Textual Do Novo TestamentoAdriano Da Silva CarvalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Nutrition Month Celebration PRES TalksDokument2 SeitenNutrition Month Celebration PRES Talksjessica bacaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- High Impact CopywritingDokument17 SeitenHigh Impact CopywritingdurvalmartinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- ARIDO Presenting World's Most Exclusive Art Offering, Multi Billion Dollar Trade Deal During Art Basel 2019Dokument2 SeitenARIDO Presenting World's Most Exclusive Art Offering, Multi Billion Dollar Trade Deal During Art Basel 2019PR.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ear Training EssentialsDokument85 SeitenEar Training EssentialsJuan Ramiro Pacheco Aguilar100% (1)

- Nokia FestDokument57 SeitenNokia Festdeva_41Noch keine Bewertungen

- Plywood ScooterDokument7 SeitenPlywood ScooterJim100% (4)

- 17 Paket Grammar PDFDokument72 Seiten17 Paket Grammar PDFSyekhmundu jambukarangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Celebrity Endorsement in IndiaDokument59 SeitenCelebrity Endorsement in Indiavikeshjha1891% (11)

- Consequences and The Difference Between KarmaDokument1 SeiteConsequences and The Difference Between Karmacosmicwitch93Noch keine Bewertungen

- PictureOfDorianGray TM 956Dokument16 SeitenPictureOfDorianGray TM 956pequen30Noch keine Bewertungen

- FORD - Leopolds and Wolfgangs View of The World (Diss)Dokument272 SeitenFORD - Leopolds and Wolfgangs View of The World (Diss)Ticiano BiancolinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 45 Poems of Bulleh ShahDokument50 Seiten45 Poems of Bulleh Shahsandehavadi33% (3)

- Mav 777Dokument2 SeitenMav 777jaystermeisterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Focus April 2021Dokument34 SeitenFocus April 2021FOCUSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Miraculous Healing by Henry W. FrostDokument69 SeitenMiraculous Healing by Henry W. FrostJames Mayuga100% (1)

- one-day-dLL COT 2nd QuarterDokument5 Seitenone-day-dLL COT 2nd Quarterwilbert giuseppe de guzmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kshama PrarthanaDokument7 SeitenKshama Prarthanaseshadri012822Noch keine Bewertungen

- Annabel LeeDokument4 SeitenAnnabel LeeMaricon DomingoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cinebook Catalogue-12 1H09Dokument25 SeitenCinebook Catalogue-12 1H09catchgops100% (1)

- Django Gypsy Jazz Guitar ManualDokument23 SeitenDjango Gypsy Jazz Guitar ManualMETREF100% (1)

- Mrs Dalloway: A Protest Against PatriarchyDokument2 SeitenMrs Dalloway: A Protest Against PatriarchyLuchi GómezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lab 1Dokument39 SeitenLab 1Nausheeda Bint ShahulNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Literature: A Wife of BathDokument32 SeitenEnglish Literature: A Wife of BathJayson CastilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Characterization of Madam Loisel From The NecklaceDokument2 SeitenCharacterization of Madam Loisel From The NecklaceNita SafitriNoch keine Bewertungen

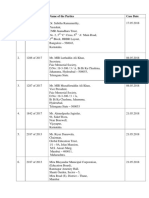

- S.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDDokument4 SeitenS.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDAasim Ahmed ShaikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Sanskrit English DictionaryDokument1.181 SeitenA Sanskrit English DictionaryAtra100% (1)

- Suraj Kund MelaDokument11 SeitenSuraj Kund MelaAayushee BajoriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Survey To American Literature 1Dokument573 SeitenSurvey To American Literature 1Mirana Rogić100% (1)

- Kino Novakino NovaDokument3 SeitenKino Novakino NovaIrfan-Semiha DugopoljacNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Plus MIDTERM ExamDokument3 SeitenEnglish Plus MIDTERM ExamRosanna Navarro100% (1)