Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

1944-7558-116 1 3 PDF

Hochgeladen von

Wahyu Agung CiptadiOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1944-7558-116 1 3 PDF

Hochgeladen von

Wahyu Agung CiptadiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Accounting for the Down Syndrome Advantage

Anna J. Esbensen

Cincinnati Childrens Hospital Medical Center

Marsha Mailick Seltzer

Waisman Center, University of WisconsinMadison

Abstract

The authors examined factors that could explain the higher levels of psychosocial well

being observed in past research in mothers of individuals with Down syndrome compared

with mothers of individuals with other types of intellectual disabilities. The authors studied

155 mothers of adults with Down syndrome, contrasting factors that might validly account

for the Down syndrome advantage (behavioral phenotype) with those that have been

portrayed in past research as artifactual (maternal age, social supports). The behavioral

phenotype predicted less pessimism, more life satisfaction, and a better quality of the

motherchild relationship. However, younger maternal age and fewer social supports, as

well as the behavioral phenotype, predicted higher levels of caregiving burden. Implications

for future research on families of individuals with Down syndrome are discussed.

DOI: 10.1352/1944-7558-116.1.3

Mothers of individuals with Down syndrome syndrome compared with mothers of children

typically exhibit better psychological well-being with other intellectual and developmental disabil-

profiles compared with mothers of individuals ities (either of unknown etiology or with other

with other intellectual and developmental disabil- specific syndromes or diagnoses). There is exten-

ities, with better outcomes being evident across sive evidence that mothers of young children with

the life course (e.g., Fidler, Hodapp, & Dykens, Down syndrome experience lower levels of stress

2000; Hauser-Cram, Warfield, Shonkoff, & Krauss, (Kasari & Sigman, 1997; Marcovitch, Goldberg,

2001; Seltzer, Krauss, & Tsunematsu, 1993). How- MacGregor, & Lojkasek, 1986), more extensive and

ever, researchers have argued that this advantage is satisfying networks of social support (Hauser-Cram

simply an artifact of confounding variables (Cahill et al., 2001; Shonkoff, Hauser-Cram, Krauss, &

& Glidden, 1996; Glidden & Cahill, 1998; Stone- Upshur, 1992), and less pessimism about their

man, 2007) or that confounding variables may childrens future (Fidler et al., 2000) and they

contribute to the advantage (Corrice & Glidden, perceive their children to have less difficult

2009). To develop a better understanding of the temperaments (Kasari & Sigman, 1997). Families

factors associated with syndrome-specific impacts with a child with Down syndrome are also more

on the family, it is important to sort out valid cohesive and harmonious than families of children

explanations that account for between-group with other types of intellectual and developmental

differences in family functioning from artifacts. disabilities (Mink, Nihira, & Meyers, 1983).

There is an abundance of literature suggesting Similar to mothers of young children, moth-

a Down syndrome advantage in mothers of ers of adolescents and young adults with Down

children, adolescents, and adults with Down syndrome also display better psychological well

E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 3

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Down syndrome advantage A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

being than mothers of similarly-aged children longer evident after controlling for factors such as

with other types of intellectual and develop- maternal age and coping, marital status, child age,

mental disabilities (Abbeduto et al., 2004). In family income, and other contextual variables

past research, mothers of adolescents with Down (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Blacher & McIntyre,

syndrome have reported less pessimism about 2006; Cahill & Glidden, 1996; Corrice & Glid-

their childs future, more closeness in the den, 2009; Eisenhower, Baker, & Blacher, 2005;

relationship with their child, and fewer depressive Glidden & Cahill, 1998; Stoneman, 2007). How-

symptoms; they have also been more likely to ever, other studies found persistent evidence of

perceive that the child reciprocated feelings of the Down syndrome advantage, even after con-

closeness compared with mothers of adolescents trolling for a variety of covariates such as maternal

with other types of intellectual and developmental age and education (Eisenhower et al., 2005; Selt-

disabilities (Abbeduto et al., 2004). In addition, zer et al., 1993). Together, these findings suggest

there is evidence that the advantage of having a that covariates cannot fully account for why

son or daughter with Down syndrome continues mothers of individuals with Down syndrome

well into adulthood (Greenberg, Seltzer, Krauss, appear to be advantaged relative to mothers of

Chou, & Hong, 2004; Seltzer, Krauss, Orsmond, individuals with other types of intellectual and

& Vestal, 2001; Seltzer et al., 1993). Mothers of developmental disabilities with respect to psycho-

adults with Down syndrome have reported less logical functioning.

conflicted family environments, less stress and A different way to address the question of

burden, more satisfaction with their social sup- what accounts for the Down syndrome advantage

ports, more optimism and acceptance of their is to examine differences within samples of

childs disability, and more appreciation for their mothers of individuals with Down syndrome.

childs strengths than have mothers of adults with Variables that have differentiated groups in

intellectual and developmental disabilities due to between-group analyses could be examined di-

other causes (Krauss & Seltzer, 1995, 2000; Seltzer rectly in a within-group analysis to determine if

et al., 1993). they are associated with the hypothesized out-

However, it should be noted that not all comes. For example, older maternal age at the

researchers have found that mothers of individu- time of the birth of the child with Down

als with Down syndrome report better psycholog- syndrome (and, hence, greater maturity and

ical well being on all measures (Cunningham, financial stability) is one explanation frequently

1996; Esbensen, Seltzer, & Abbeduto, 2008; Gath, offered for the Down syndrome advantage (Cahill

1990; Greenberg et al., 2004; Roach, Orsmond, & & Glidden, 1996; Corrice & Glidden, 2009;

Barratt, 1999; Sanders & Morgan, 1997). Instead, Glidden & Cahill, 1998; Stoneman, 2007). In a

in some studies, mothers of individuals with within-group analysis, it would be possible to

Down syndrome have reported similar rates to the assess whether mothers who were older at the age

comparison group with intellectual and develop- of the birth of their child with Down syndrome

mental disabilities on some (but not all) measures would have better well-being outcomes than

of psychological well being, such as depressed mothers who were younger. Another explanation

mood, pessimism and marital satisfaction. Yet, that is frequently offered for the Down syndrome

the bulk of the evidence suggests that mothers advantage is that mothers of individuals with

of individuals with Down syndrome have a Down syndrome have greater access to syndrome-

more normative pattern of psychological well specific support groups than mothers of individ-

being than mothers of children and adults with uals with other types of intellectual and develop-

other types of intellectual and developmental mental disabilities. Support groups for a particular

disabilities. syndrome provide families with information

Despite the empirical evidence in favor of a pertinent to their childs specific behaviors and

Down syndrome advantage, Corrice and Glid- characteristics, offer mothers social support, and

den (2009) posited that this advantage may be an can lead to more adaptive coping (Erickson &

artifact of sampling bias or between-group differ- Upsur, 1989). Mothers of children with Down

ences in other factors (e.g., maternal age) that may syndrome are also reported to receive more family

contribute to the association of maternal func- support than mothers of children with other

tioning and the diagnosis of her child. In some disorders and to have larger social support

research, the Down syndrome advantage was no networks (Poehlmann, Clements, Abbeduto, &

4 E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Down syndrome advantage A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

Farsad, 2005; Seltzer & Krauss, 1998). Again, in a larger social networks and who participate in

within-group analysis, it would be possible to parent support groups will have better well being,

determine whether those mothers with greater and (c) mothers of adults with higher levels of

support actually have more favorable well-being functional abilities and fewer behavior problems

outcomes than mothers who have less support. will have better well being. Support for the first

Whereas older maternal age and greater social two of these hypotheses would support the

support can be conceptualized as artifacts that argument that the Down syndrome advantage is

may account for the Down syndrome advantage, artifactual, whereas support of the latter hypoth-

an alternative explanation concerns the level of esis would suggest that the advantage is due, at

stress associated with parenting a child with Down least in part, to differential levels of parenting

syndrome compared with the parenting stress stress.

associated with other types of intellectual and

developmental disabilities. Children with Down

syndrome are commonly described as affection- Method

ate, sociable, and easy in temperament (Dykens,

Participants

1999). Individuals with Down syndrome also

The current sample was drawn from a larger

exhibit better functional abilities and fewer

longitudinal study of mothers age 55 and older

behavior problems than individuals with other

caring for an adult son or daughter with intel-

types of intellectual and developmental disabili-

lectual and developmental disabilities (Krauss &

ties (Corrice & Glidden, 2009; Greenspan &

Seltzer, 1999). From 1988 to 2000, eight waves of

Delaney, 1983; Harrison, 1987; Hodapp & Dykens,

1994; Loveland & Kelley, 1988; Zigman et al., data were collected at 18-month intervals with an

1987). Such a profile of the behavioral phenotype initial sample of 461 adults with intellectual and

of individuals with Down syndrome could explain developmental disabilities who lived at home, 169

lower levels of parenting stress and suggests a of whom had Down syndrome. At the second

nonartifactual (i.e., valid) explanation of the Down wave of data collection (19891990), mothers of

syndrome advantage in maternal psychological 155 adults with Down syndrome continued to

well being. participate, and they formed the sample for the

In the current analysis, we examined the present analysis. The second wave of data

impact of maternal age, social supports, and the collection was selected for analysis because it

behavioral phenotype of the son or daughter with was the first point when behavior problems were

Down syndrome on the well being of their measured.

mothers. We focused this within-group analysis At the time that they gave birth to their child

on mothers of individuals with Down syndrome with Down syndrome, the mothers in our sample

to test whether artifactual (i.e., maternal age and ranged in age from 20 to 47 years (M 5 35.6, SD

social supports) or valid (i.e., behavioral pheno- 5 6.1). They were primarily Caucasian (98.7%),

type) factors account for advantages in maternal and 80.6% had graduated from high school or had

well being. We also focused on four positive and at least some postsecondary education. They had

negative maternal well being outcomes to deter- between 1 and 9 children, including their son or

mine if the effects of these variables vary across daughter with Down syndrome (M 5 4.3, SD 5

different outcomes. Specifically, we examined the 2.0). At the second wave of data collection of the

influence of maternal age, maternal supports, and ongoing study, which is the time point of focus in

the behavioral phenotype of the adult with Down the present study, mothers ranged in age from 56

syndrome on maternal well being, as measured by to 86 years (M 5 67.9, SD 5 6.7). Two-thirds were

life satisfaction, the quality of the mothers married (65.2%), and nearly one-third (30.3%)

relationship with her son or daughter with Down were widowed. The median family income was

syndrome, maternal pessimism about the son or between $15,000 and $19,999, which was typical

daughters future, and subjective caregiving bur- for older household incomes at that time (U.S.

den, in a sample of mothers of adults with Down Census Bureau, 2005). The adult child with Down

syndrome. We hypothesized that (a) mothers who syndrome ranged in age from 17 to 56 years (M 5

were older when they gave birth to their child 32.4, SD 5 7.4). Nearly two-thirds were males

with Down syndrome will have better well being, (61.3%) and three-fourths had mild or moder-

(b) mothers of adults with Down syndrome with ate intellectual disability (76.5%) and the remain-

E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 5

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Down syndrome advantage A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

ing adults had severe or profound intellectual The Pessimism subscale from the Question-

disability. naire on Resources and Stress-F (Friedrich et al.,

1983) was used to measure maternal pessimism

Instruments about her childs future. The 11-item Pessimism

Maternal well being. Four dimensions of subscale asked whether the mother has concerns

maternal well being were assessed: life satisfaction, about her childs future and potential for

quality of the mothers relationship with her adult achieving self-sufficiency. Internal consistency

child with Down syndrome, pessimism about her was found to be .77 in the larger longitudinal

adult childs future, and subjective caregiving study (Esbensen et al., 2006) and .75 in the

burden. Differences between the mothers of current sample.

adults with Down syndrome and mothers of The Zarit Burden Interview (Zarit et al., 1980)

adults with other types of intellectual and is a 29-item measure of subjective burden related

developmental disabilities have already been to caregiving, rated on a 3-point scale. Subjective

published (Seltzer et al., 1993), supporting the burden represents potential problems a mother

Down syndrome advantage. The present sample may experience as a result of caregiving for her

included 92% of the mothers in Seltzer et al.s son or daughter. Mothers indicated how much

discomfort was caused by each item. The internal

sample, and the between-group Down syndrome

consistency for this instrument was .83 in the

advantage was also evident in the current sample

larger longitudinal study (Esbensen et al., 2006)

(data available from first author [A. E.]). We also

and .81 in the current sample.

checked whether the range of scores for these

Health. Maternal and child health was mea-

outcome variables in this sample with Down

sured using a maternal rating of current health

syndrome was restricted, or whether the range

status (1 5 poor, 2 5 fair, 3 5 good, 4 5 excellent).

overlapped with the scores of the group with

Global ratings of health have been found to be

intellectual and developmental disabilities but

accurate measures of health status (Idler &

without Down syndrome in the same study (data

Benyamini, 1997). Mothers and the sons or

available from first author). There was no daughters with Down syndrome were both

restriction of range in the data from mothers of primarily in good health (M 5 2.9, SD 5 0.8;

adults with Down syndrome relative to mothers M 5 3.4, SD 5 0.7, respectively).

of adults with other types of intellectual and Maternal social supports. Mothers reported on

developmental disabilities. individuals in her personal network, including

The Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale family and friends, with whom they felt a special

Scale (PGC; Lawton, 1972) was used to measure bond (Antonucci & Akiyama, 1987). Network size

maternal life satisfaction, defined as a basic sense was assessed as the total number of people in the

of satisfaction with oneself, a feeling that there is a social support network and ranged from 0 to 14

place in the environment for oneself, and an (M 5 8.2, SD 5 3.3). Mothers also reported if

acceptance of what cannot be changed (p. 148). they currently participated in a parent support

This 17-item scale consists of yes or no questions group. More than one third (39.6%) of mothers

and had an internal consistency coefficient of .84 participated in such a group.

in the larger longitudinal study (Krauss & Seltzer, Behavioral phenotype. Behavioral phenotype

1993) and.81 in the current sample. was assessed using measures of functional abilities

The Positive Affect Index (PAI; Bengtson & and behavior problems. Our measure of func-

Schrader, 1982) was used to measure the mothers tional abilities was a 30-item scale measuring

perception of the quality of her relationship with functional skills in the areas of housework,

her adult son or daughter. This 10-item scale personal care, meal-related activities, and mobil-

assesses the mothers feelings toward her child and ity. This measure of functional skills was based on

her perception of her childs feelings toward her. a revised version of the Barthel Index (Mahoney &

Items relate to feelings of intimacy, trust, Barthel, 1965) to measure personal and instru-

understanding, fairness, and respect and are rated mental activities of daily living appropriate for

on a 6-point scale. Internal consistency for the adults with intellectual and developmental dis-

PAI was .87 in the larger longitudinal study abilities (Seltzer, Ivry, & Litchfield, 1987). Each

(Esbensen, Seltzer, & Greenberg, 2006) and .88 in item was rated on a 4-point scale of independence

the current sample. (0 5 cannot perform the task at all, 1 5 could do but

6 E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Down syndrome advantage A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

doesnt, 2 5 can perform the task with help, 3 5 Table 1. Mean, Standard Deviation, and Range

performs the task independently) and averaged for a of Study Variables

total score. Internal consistency coefficient for the

Variable M SD Range

total score was .90 in the larger longitudinal study

(Esbensen, Seltzer, & Greenberg, 2007) and .93 in Life satisfaction 12.90 3.61 117

the current sample. Average functional ability Relationship with

scores ranged from 0.53 to 2.93 (M 5 2.3, SD 5 adult child 51.46 5.35 3360

0.4). Pessimism 6.10 2.72 011

We used the Inventory for Client and Agency Subjective burden 27.94 6.23 1857

Planning (ICAP; Bruininks, Hill, Weatherman, &

Woodcock, 1986; later known as the Scales of

model. Social support was entered in the third

Independent BehaviorRevised [SIB-R; Brui-

step and included size of maternal social network

ninks, Woodcock, Weatherman, & Hill, 1996]) and whether the mother attended a parent

to measure behavior problems. This measure support group. In the fourth step, child behavioral

assessed the frequency and severity of eight types phenotype variables were added, including total

of behavior problems, providing an overall functional abilities and generalized behavior

measure of generalized behavior problems. Indi- problems.

vidual problem behaviors are scored as present or

absent. Index scores provide ratings of the

seriousness of the problem behavior as subclinical Results

(90110), marginally serious (111120), moderately The means, standard deviations, and ranges

serious (121130), serious (131140), or very serious for the four measures of maternal well being are

($141). Reliability and validity are excellent presented in Table 1. Intercorrelations of study

(Bruininks et al., 1986). Generalized behavior variables are presented in Table 2. Tables 3 and 4

problem scores ranged from 96 to 141 (M 5 99.3, present regression models examining how mater-

SD 5 5.7). nal age, maternal supports, and child behavioral

phenotype were associated with the four measures

Data Analysis of maternal well being, after controlling for

We used multiple hierarchical regression to maternal and child background characteristics.

test the extent to which maternal age, social

support, and child behavioral phenotype would Life Satisfaction

predict maternal well being (life satisfaction, the As shown in Table 3, among the control

quality of the mothers relationship with her son variables (Step 1), only maternal health predicted

or daughter, pessimism, and subjective burden), life satisfaction, with better health predictive of

after controlling for maternal and child covariates. higher levels of life satisfaction. Neither maternal

Maternal and child background characteristics age at the birth of the child with Down syndrome

were entered in the first step of the regression nor social supports had a significant influence on

model. Maternal covariates included number of maternal life satisfaction (Steps 2 and 3), counter

children, family income, marital status, maternal to Hypotheses 1 and 2. However, having greater

education, and maternal health. Child covariates behavior problems (Step 4) was predictive of

included gender, child health, and child age. lower levels of life satisfaction in mothers of

Child age and current maternal age were signif- adults with Down syndrome, which was partially

icantly correlated (r 5 .62, p , .001) and, supportive of Hypothesis 3.

together, were redundant with the theoretically

important variable of age of the mother at the Quality of Relationship

birth of her child with Down syndrome. Because As shown in Table 3, among the control

there was greater variability in child age, this variables, only child health predicted the quality

covariate was entered in the model instead of of the relationship between the mother and her

current maternal age. son or daughter with Down syndrome, with better

To test the research hypotheses, maternal age child health predicting a better quality relation-

at the birth of her child with Down syndrome was ship. Neither maternal age when she gave birth to

entered in the second step of the regression her child with Down syndrome nor social

E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 7

8

Table 2. Intercorrelations of Study Variables

VOLUME

Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

1. Number of

116,

children

2. Family

NUMBER

income 2.08

3. Marital

status .03 .42*

Down syndrome advantage

1: 315 |

4. Maternal

education 2.19* .31* .07

5. Maternal

JANUARY

health .10 .30* .18* .18*

2011

6. Child gender 2.04 2.18* 2.06 .01 .02

7. Child health .13 .24* .07 2.07 .33* 2.06

8. Child age 2.22* 2.16* 2.29* 2.04 2.05 .06 2.01

9. Maternal age

at birth .18* 2.22* 2.01 .02 2.17* 2.13 2.12 2.52*

10. Size of social

network .15 .25* .23* .16* .17* 2.01 .06 2.14 2.03

11. Attend

parent group .04 2.08 2.00 2.02 2.04 2.09 2.04 2.06 .24* .03

12. Functional

abilities .13 .09 .08 .02 .13 2.07 .14 .12 2.14 .10 .02

13. Generalized

behavior 2.02 .07 .11 2.11 2.16 .05 .00 2.14 .10 .02 2.05 2.26*

14. Life

satisfaction .07 .21* .07 .14 .45* 2.19* .17* 2.02 2.00 .11 .02 .12 2.30*

15. Relationship

with child 2.09 .03 .00 .07 .06 2.04 .27* .10 2.07 .07 .01 .15 2.36* .12

16. Pessimism 2.11 2.06 2.02 .02 2.10 .12 2.12 2.09 .08 2.19* 2.02 2.24* .30* 2.34* 2.30*

17. Subjective

burden 2.16 2.11 2.14 .09 2.26* .20* 2.28* 2.10 .02 2.20* 2.06 2.22* .28* 2.54* 2.34* .62*

*p , .05.

E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

AJIDD

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Down syndrome advantage A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

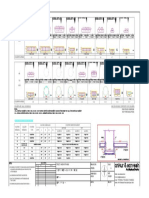

Table 3. Hierarchical Regression Analysis for the Prediction of Life Satisfaction and Relationship

Quality

Life satisfaction Relationship with adult child

Variable Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4 Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4

Step 1: Maternal and child background characteristics

Number of

children .05 .05 .04 .03 2.10 2.10 2.12 2.13

Family income .04 .07 .07 .09 2.10 2.08 2.10 2.05

Marital status 2.01 .00 2.01 .02 .02 .03 .01 .04

Maternal

education .11 .10 .10 .08 .06 .05 .05 2.00

Maternal health .41** .42** .42** .37** 2.03 2.02 2.03 2.09

Child gender 2.16 2.15 2.15 2.13 2.05 2.05 2.05 2.01

Child health 2.01 .01 .01 .02 .32** .32** .32** .32**

Child age .06 .13 .14 .12 .07 .09 .09 .06

Step 2: Age variable

Maternal age at

birth of child

with DS .11 .10 .11 .02 .03 .06

Step 3: Maternal social support

Size of social

network .05 .06 .07 .08

Attend parent

group .04 .03 .00 2.02

Step 4: Child behavioral phenotype

Functional abilities 2.06 .05

Behavior problems 2.26** 2.35**

DR2 .24** .01 .00 .06* .11** .00 .00 .12**

Note. DS 5 Down syndrome. Marital status coded: 0 5 single/divorced/widowed, 1 5 married; maternal education coded: 0

5 some college or less, 1 5 college degree or higher; gender coded: 0 5 male, 1 5 female; attend parent group coded: 0 5 no, 1 5

yes. b coefficients presented in table.

*p , .05. ** p , .01.

supports had a significant influence on mother levels of behavior problems were predictive of

child relationship quality in adulthood, counter greater pessimism. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was

to Hypotheses 1 and 2. However, greater behavior partially supported.

problems were predictive of poorer relationship

quality in adulthood, which was partially sup- Subjective Burden

portive of Hypothesis 3. In contrast to the prediction of the above

three measures of maternal well being, the factors

Pessimism that are associated with maternal subjective

As shown in Table 4, no control variables burden are more complex. As shown in Table 4,

predicted maternal pessimism. Neither maternal among the control variables, maternal health and

age when she gave birth to her child with Down child age and gender were predictive of subjective

syndrome nor current social supports had a burden in Step 1, and, by Step 4, maternal marital

significant influence on maternal pessimism, status and child age, gender, and health were

counter to Hypothesis 1 and 2. However, higher significant predictors of subjective burden. Moth-

E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 9

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Down syndrome advantage A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

Table 4. Hierarchical Regression Analysis for the Prediction of Pessimism and Subjective Burden

Pessimism Burden

Variable Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4 Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4

Step 1: Maternal and child background characteristics

Number of

children 2.14 2.14 2.11 2.08 2.10 2.08 2.05 2.03

Family income 2.02 2.01 .00 2.04 .14 .09 .10 .04

Marital status 2.05 2.04 2.02 2.03 2.17 2.18 2.16 2.19*

Maternal

education 2.01 2.01 .01 .04 2.02 2.00 .01 .06

Maternal health 2.06 2.06 2.05 .01 2.20* 2.22* 2.21* 2.16

Child gender .12 .12 .12 .09 .22 .21* .21* .18*

Child health 2.06 2.06 2.05 2.05 2.19* 2.20* 2.19* 2.19*

Child age 2.14 2.13 2.14 2.11 2.21* 2.30** 2.32** 2.32*

Step 2: Age variable

Maternal age at

birth of child

with DS .01 .02 2.02 2.15 2.16 2.20*

Step 3: Maternal social support

Size of social

network 2.17 2.17 2.18* 2.19*

Attend parent

group 2.04 2.02 2.03 .00

Step 4: Child behavioral phenotype

Functional

abilities 2.12 2.00

Behavior

problems .27** .31**

DR2 .06 .00 .03 .10** .20** .01 .03 .09**

Note. DS 5 Down syndrome. Marital status coded: 0 5 single/divorced/widowed, 1 5 married; maternal education coded: 0

5 some college or less, 1 5 college degree or higher; gender coded: 0 5 male, 1 5 female; attend parent group coded: 0 5 no, 1 5

yes. b coefficients presented in table.

*p , .05. ** p , .01.

ers not currently married (primarily widows) were

more burdened than those who were married, and Discussion

mothers of daughters with Down syndrome who We examined, in a within-group analysis of

were in poorer health and whose child was mothers of adults with Down syndrome, whether

younger in age felt more burdened. In addition, artifactual or valid factors accounted for advan-

mothers who were older when they gave birth to tages in well being. Our findings suggest that it

their child with Down syndrome and who had may be problematic to infer, from between-group

larger social support networks had less subjective comparisons, explanations for why a particular

burden. These findings support Hypotheses 1 and group of mothers of individuals with intellectual

2. In addition, fewer behavior problems signifi- and developmental disabilities manifest their

cantly predicted less subjective burden, partially distinctive profiles of well being, without checking

supporting Hypothesis 3. whether these explanations hold up in within-

10 E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Down syndrome advantage A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

group studies. Pairing between-group comparative age were strongly correlated in our sample, our

analyses with within-group investigations may findings are consistent with the literature that

yield a stronger understanding of the factors that older mothers commonly report better maternal

account for well-being profiles in mothers of well being than younger mothers (Esbensen,

individuals with different types of intellectual and Seltzer, & Abbeduto, 2008; Krauss & Seltzer,

developmental disabilities than either analytic 1995). Our finding that mothers of daughters

approach alone. In general, we found that, among reported more burden is new. A closer examina-

mothers of adults with Down syndrome, older tion on an item level of gender differences in

maternal age and access to social supports were perceived caregiving burden suggested that this

not related to three of our four measures of finding was driven by maternal feelings of not

maternal well being, even though these factors receiving needed support from family and having

have differentiated such mothers from their to manage multiple roles (e.g., family, work). The

counterparts whose children had other types of impact of the gender of the child with Down

intellectual and developmental disabilities in past syndrome on maternal well being warrants

research. However, we found a different pattern of additional examination. Maternal burden is a

predictors for one measure of maternal well being, role-specific measure of well being, and, thus, the

implicating both factors that have been portrayed specific circumstances of the caregiving context

as artifactual as well as those that have been may be more significant than with more general

considered to be valid. measures.

Specifically, for the outcomes of life satisfac- Our findings also have implications for

tion, quality of the mothers relationship with her service provision for adults with Down syndrome

son or daughter with Down syndrome, pessimism, and their mothers. One of the maternal charac-

maternal age at birth of her child with Down teristics that consistently played a role in the

syndrome, and social supports were not signifi- present analysis in predicting maternal well being

cant predictors. Instead, the Down syndrome was maternal health. Sample mothers were in their

behavioral phenotype of having fewer behavior late 60s, so, naturally, their own health problems

problems contributed the most to better out- would have played a large role in predicting their

comes, net of all other variables. This finding psychological well being (life satisfaction and

suggests that the Down syndrome advantage subjective burden). This pattern persisted even

found for these three maternal outcomes may be when we substituted maternal age for child age in

valid, not artifactual. It is noteworthy that the the regression model (data available from the first

aspect of the Down syndrome behavioral pheno- author [A. E.]). However, maternal health did not

type that most strongly predicted maternal well play a significant role in predicting the quality of

being was not functional abilities but behavior the relationship with the mothers son or

problems. This finding points to the importance daughter. Instead, child health influenced the

of treating behavior problems in adulthood, even quality of the motherchild relationship. This

among adults with Down syndrome. finding further underscores the importance of

A different pattern was found with respect to providing quality health care to individuals with

maternal subjective burden. Both variables con- Down syndrome as they age, as well as to their

ceptualized by others as artifacts (older maternal mothers, because our past research has document-

age and greater social support) as well as the ed the health declines that accompany advancing

Down syndrome behavioral phenotype were age in adults with Down syndrome (Esbensen,

found to contribute to maternal subjective Seltzer, & Krauss, 2008).

burden, suggesting that accounting for the Down One limitation of this analysis is that it was

syndrome advantage with respect to subjective based on a sample of mothers of adult children

burden was more complex than with the other with Down syndrome, by taking advantage of a

measures of maternal well being we examined. In previously collected dataset. We do not know if

addition, several other maternal and child char- the same pattern of findings would have been

acteristics also had a significant role in predicting observed among mothers at earlier stages of the

this outcome, including maternal marital status life course of their child. It may be that maternal

and child age and gender. Widows, mothers of age at the time of the childs birth is a more salient

daughters, and mothers of younger adult children protective factor for mothers of young children

felt more burdened. Because child and maternal than for mothers of adults. On the other hand,

E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 11

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Down syndrome advantage A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

theories of cumulative advantage across the life premutation, both of which have been shown to

course (Ryff, Singer, Love, & Essex, 1998) have have mental health comorbidities independent of

suggested that if maternal age confers an early parenting stress (Seltzer et al., 2009). It is possible

advantage to mothers of children with Down that, as a group, mothers of individuals with

syndrome, this advantage should become magni- Down syndrome may have better well-being

fied over time. Given the longer lifespan of adults profiles than mothers of individuals with autism

with Down syndrome and, for many, the spectrum disorder or fragile X syndrome in part

concomitant longer period of coresidence with because of differential biological vulnerability as

the mother, the persistence of patterns across the well as differential levels of parenting stress.

full life course is a highly salient issue for research, This study contributes to the understanding

policy, and provision of services to these families. of the Down syndrome advantage. Our findings

In our sample, social support did not suggest that a diagnosis of Down syndrome

contribute to several measures of maternal confers an advantage with respect to maternal

psychological well being. However, there are well being and that this advantage is not merely

other methods of measuring social support, an artifact. However, depending on the measure

indicating that our findings warrant replication of maternal well being of interest, understanding

before the contribution of social support is the Down syndrome advantage can be complex,

discounted as being a contributor to the Down with multiple family and child characteristics also

syndrome advantage (Cohen, Underwood, & contributing to enhanced maternal well being.

Gottlieb, 2000). Another limitation in this study The next step in this line of investigation is to

is that the current sample was based on a examine what accounts for the Down syndrome

volunteer, largely Caucasian sample. The current advantage among mothers of younger children

sample also relied on only maternal informants and adolescents. The better we understand what

and concurrent measures, which introduces accounts for the Down syndrome advantage, the

shared method variance to the analyses, possibly better we will be able to inform and support

masking other significant findings. Furthermore, families of individuals with Down syndrome.

the models accounted for only a portion of the

variance in maternal well being (range 5 22%

30%), suggesting that there is much additional References

research to be conducted to fully understand

maternal well being in the later years of the life Abbeduto, L., Seltzer, M. M., Shattuck, P., Krauss,

course among mothers of individuals with Down M. W., Orsmond, G., & Murphy, M. M.

syndrome. (2004). Psychological well-being and coping

An additional explanation for the Down in mothers of youths with autism, Down

syndrome advantage is that some of the groups syndrome, or fragile X syndrome. American

to which mothers of individuals with Down Journal on Mental Retardation, 109, 237254.

syndrome have been compared may themselves Antonucci, T. C., & Akiyama, H. (1987). An

bear biological vulnerability to poor well-being examination of sex differences in social

outcomes, separate from any reactive effects of support among older men and women. Sex

parenting. Whereas Down syndrome is a sporadic Roles, 17, 737749.

condition, not passed on from the parent to the Bengtson, V. L., & Schrader, S. S. (1982). Parent-

child, this is not the case for all types of child relations. In D. J. Mangen & W. A.

intellectual and developmental disabilities. For Peterson (Eds.), Research instruments in social

example, some mothers of individuals with autism gerontology: Vol 2. Social roles and social

spectrum disorders are believed to have the participation (pp. 115155). Minneapolis: Uni-

broader autism phenotype (Piven, Palmer, Jacobi, versity of Minnesota Press.

Childress, & Arndt, 1997), which may predispose Blacher, J., & McIntyre, L. L. (2006). Syndrome

them to higher levels of depression, anxiety, and specificity and behavioural disorders in young

other indicators of poorer psychological function- adults with intellectual disability: Cultural

ing, independent of the stressful behaviors of their differences in family impact. Journal of

child with autism spectrum disorder. Similarly, Intellectual Disability Research, 50, 184198.

mothers of children with fragile X syndrome have Bruininks, R. H., Hill, B. K., Weatherman, R. F.,

either the full mutation of fragile X or the & Woodcock, R. W. (1986). Inventory for client

12 E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Down syndrome advantage A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

and agency planning (ICAP). Allen, TX: DLM adults with and without Down syndrome

Teaching Resources. living with family. Journal of Intellectual

Bruininks, R. H., Woodcock, R. W., Weather- Disability Research, 51, 10391050.

man, R. E., & Hill, B. K. (1996). Scales of Esbensen, A. J., Seltzer, M. M., & Krauss, M. W.

Independent BehaviorRevised comprehensive (2008). Stability and change in health, func-

manual. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing. tional abilities and behavior problems among

Cahill, B. M., & Glidden, L. M. (1996). Influence adults with and without Down syndrome.

of child diagnosis on family and parental American Journal on Mental Retardation, 113,

functioning: Down syndrome versus other 263277.

disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retar- Fidler, D. J., Hodapp, R. M., & Dykens, E. M.

dation, 101, 149160. (2000). Stress in families of young children

Cohen, S., Underwood, L. G., & Gottlieb, B. H. with Down syndrome, Williams syndrome,

(2000). Social support measurement and and Smith-Magenis syndrome. Early Educa-

intervention: A guide for health and social tion and Development, 11, 395406.

scientists. New York: Oxford University Press. Gath, A. (1990). Down syndrome children and

Corrice, A. M., & Glidden, L. M. (2009). The their families. American Journal of Medical

Down syndrome advantage: Fact or fiction? Genetics Supplement, 7, 314316.

American Journal on Intellectual and Develop- Gatz, M., & Hurwicz, M. L. (1990). Are old

mental Disabilities, 114, 254268. people more depressed? Cross-sectional data

Cunningham, C. C. (1996). Families of children on Center for Epidemiological Studies De-

with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Re- pression Scale factors. Psychology and Aging, 5,

search and Practice, 4, 8795. 284290.

Dykens, E. M. (1999). Direct effects of genetic Glidden, L. M., & Cahill, B. M. (1998). Successful

mental retardation syndromes: Maladaptive adoption of children with Down syndrome

behavior and psychopathology. In L. M. and other developmental disabilities. Adop-

Glidden (Ed.), International review of research tion Quarterly, 1, 2744.

in mental retardation (Vol. 22, pp. 126). San Greenberg, J. S., Seltzer, M. M., Krauss, M. W.,

Diego, CA: Academic Press. Chou, R. J., & Hong, J. (2004). The effect of

Eisenhower, A. S., Baker, B. L., & Blacher, J. quality of the relationship between mothers

(2005). Preschool children with intellectual and adult children with schizophrenia, autism

disability: Syndrome specificity, behavior or Down syndrome on maternal well-being:

problems, and maternal well-being. Journal of The mediating role of optimism. American

Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 657671. Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74, 1425.

Erickson, M., & Upsur, C. C. (1989). Caretaking Greenspan, S., & Delaney, K. (1983). Personal

burden and social support: Comparison of competence of institutionalized adult males

mothers of infants with and without disabil- with or without Down syndrome. Ameri-

ities. American Journal on Mental Retardation, can Journal of Mental Deficiency, 88, 218

94, 250258. 220.

Esbensen, A. J., Seltzer, M. M., & Abbeduto, L. Harrison, P. L. (1987). Research with adaptive

(2008). Family well-being in Down syndrome behavior scales. Journal of Special Education,

and fragile X syndrome. In J. E. Roberts, R. 21, 3768.

Chapman, & S. Warren (Eds.), Speech and Hauser-Cram, P., Warfield, M. E., Shonkoff, J. P.,

language development and intervention in Down & Krauss, M. W. (2001). Children with

syndrome and fragile X syndrome. Baltimore: disabilities: A longitudinal study of child

Brookes. development and parent well-being. Mono-

Esbensen, A. J., Seltzer, M. M., & Greenberg, J. S. graphs of the Society for Research in Child

(2006). Depressive symptoms of adults with Development, 66, Serial No. 266.

mild to moderate intellectual disability and Himmelfarb, S., & Murrell, S. A. (1983). Reliabil-

their relation to maternal well-being. Journal ity and validity of five mental health scales in

of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, older persons. Journal of Gerontology, 38, 333

3, 229237. 339.

Esbensen, A. J., Seltzer, M. M., & Greenberg, J. S. Hodapp, R. M., & Dykens, E. M. (1994). Mental

(2007). Factors predicting mortality in midlife retardations two cultures of behavioral re-

E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 13

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Down syndrome advantage A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

search. American Journal on Mental Retarda- TMR children. American Journal of Mental

tion, 98, 675687. Deficiency, 87, 484497.

Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated Piven, J., Palmer, P., Jacobi, D., Childress, D., &

health and mortality: A review of twenty- Arndt, S. (1997). Broader autism phenotype:

seven community studies. Journal of Health Evidence form a family history study of

and Social Behavior, 38, 2137. multiple-incidence autism families. American

Kasari, C., & Sigman, M. (1997). Linking parental Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 185190.

perceptions to interactions in young children Poehlmann, J., Clements, M., Abbeduto, L., &

with autism. Journal of Autism and Develop- Farsad, V. (2005). Family experiences associ-

mental Disorders, 27, 3957. ated with a childs diagnosis of fragile X or

Krauss, M. W., & Seltzer, M. M. (1993). Current Down syndrome: Evidence for disruption and

well-being and future plans of older caregiv- resilience. Mental Retardation, 43, 255267.

ing mothers. Irish Journal of Psychology, 14, Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-

4764. report depression scale for research in the

Krauss, M. W., & Seltzer, M. M. (1995). Long- general population. Applied Psychological Mea-

term caring: Family experiences over the life surement, 1, 385401.

course. In L. Nadel & D. Rosenthal (Eds.), Roach, M. A., Orsmond, G., I, & Barratt, M. S.

Down syndrome: Living and learning in the (1999). Mothers and fathers of children with

community (pp. 9198). New York: Wiley- Down syndrome: Parental stress and involve-

Liss. ment in childcare. American Journal on Mental

Krauss, M. W., & Seltzer, M. M. (1999). An Retardation, 104, 422436.

unanticipated life: The impact of lifelong Ryff, C. D., Singer, B., Love, G. D., & Essex, M. J.

caregiving. In H. Bersani, Jr. (Ed.), Responding (1998). Resilience in adulthood and later life:

to the challenge: Current trends and international Defining features and dynamic process. In J.

issues in developmental disabilities (pp. 173187). Lomranz (Ed.), Handbook of aging and mental

Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books. health: An integrative approach (pp. 6996)..

Krauss, M. W., & Seltzer, M. M. (2000). An New York: Plenum.

unanticipated life: The impact of lifelong Sanders, J. L., & Morgan, S. B. (1997). Family

caregiving. In H. Bersani, Jr. (Ed.), Responding stress and adjustment as perceived by children

to the challenge: International trends and current with autism or Down syndrome: Implications

issues in developmental disabilities (pp. 173188). for intervention. Child and Family Behavior

Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books. Therapy, 19, 1532.

Lawton, M. P. (1972). The dimensions of morale. Seltzer, M. M., Abbeduto, L., Greenberg, J. S.,

In D. Kent, R. Kastenbaum, & S. Sherwood Almeida, D., Hong, J., & Witt, W. (2009).

(Eds.), Research, planning, and action for the Biomarkers in the study of families of

elderly (pp. 144165). New York: Behavioral children with developmental disabilities. In

Publications. L. M. Glidden & M. M. Seltzer (Eds.),

Loveland, K. A., & Kelley, M. L. (1988). International review of research on mental

Development of adaptive behavior in adoles- retardation (Vol. 37, pp. 213250). New York:

cents and young adults with autism and Academic Press.

Down syndrome. American Journal on Mental Seltzer, M. M., Ivry, J., & Litchfield, L. C. (1987).

Retardation, 93, 8492. Family members as case managers: Partner-

Marcovitch, S., Goldberg, S., MacGregor, D., & ship between the formal and informal support

Lojkasek, M. (1986). Patterns of temperament networks. The Gerontologist, 27, 722728.

in three groups of developmentally delayed Seltzer, M. M., & Krauss, M. W. (1998). Families

preschool children: Mother and father rat- of adults with Down syndrome. In J. F.

ings. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 7, Miller, M. Leddy, & L. A. Leavitt (Eds.),

247252. Improving the communication of people with

Mahoney, F. E., & Barthel, D. W. (1965). Down syndrome (pp. 217240). Baltimore:

Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. Brookes.

Maryland State Medical Journal, 14, 6165. Seltzer, M. M., Krauss, M. W., Orsmond, G. I., &

Mink, I. T., Nihira, E., & Meyers, C. E. (1983). Vestal, C. (2001). Families of adolescents and

Taxonomy of family life styles: In homes with adults with autism: Uncharted territory. In L.

14 E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

VOLUME 116, NUMBER 1: 315 | JANUARY 2011 AJIDD

Down syndrome advantage A. J. Esbensen and M. M. Seltzer

M. Glidden (Ed.), International review of 1987 to 2004. Retrieved December 15, 2009,

research in mental retardation (Vol. 23, pp. from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/

267294). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. histinc/h10w.html

Seltzer, M. M., Krauss, M. W., & Tsunematsu, N. Zarit, S. H., Reever, K. E., & Bach-Peterson, J.

(1993). Adults with Down syndrome and their (1980). Relatives of the impaired elderly:

aging mothers: Diagnostic group differences. Correlates of feelings of burden. The Geron-

American Journal on Mental Retardation, 97, tologist, 20, 649655.

464508. Zigman, W. B., Schupf, N., Lubin, R. A., &

Shonkoff, J. P., Hauser-Cram, P., Krauss, M. W., Silverman, W. P. (1987). Premature regression

& Upshur, C. (1992). Development of infants of adults with Down syndrome. American

with disabilities and their families: Implica- Journal of Mental Deficiency, 92, 161168.

tions for theory and service delivery. Mono-

graphs of the Society for Research in Child Received 3/27/2009, accepted 11/24/2009.

Development, 57, Serial No. 6. Chicago: Editor-in-Charge: Marc Tasse

University of Chicago Press.

Stoneman, Z. (2007). Examining the Down Correspondence regarding this article should be

syndrome advantage: Mothers and fathers of sent to Anna Esbensen, Cincinnati Childrens

young children with disabilities. Journal of Hospital Medical Center, Division of Develop-

Intellectual Disability Research, 51, 10061017. mental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 3430 Burnet

U.S. Census Bureau. (2005). Age of head of Ave., MLC 4002, Cincinnati, OH 45229. E-mail:

household: White by median and mean income: anna.esbensen@cchmc.org

E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 15

Erratum

In the article Accounting for the Down Syndrome Advantage (A. J. Esbensen & M. M. Seltzer.

(2011). American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, Vol. 116, Issue 1, pp. 315; doi:

10.1352/1944-7558-116.1.3), the following acknowledgment was omitted:

This manuscript was prepared with support from the National Institute on Aging (Grant R01

AG08768, M. M. Seltzer, principal investigator) and the National Institute on Child Health &

Human Development (Grants R03 HD59848, A. J. Esbensen, principal investigator, and P30

HD03352, M. M. Seltzer, principal investigator). We also thank the families who participated in this

research.

ii E American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersVon EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Psychological Well-Being and Coping in Mothers of Youths With Autism, Down Syndrome, or Fragile X SyndromeDokument18 SeitenPsychological Well-Being and Coping in Mothers of Youths With Autism, Down Syndrome, or Fragile X SyndromeAncuța IfteneNoch keine Bewertungen

- O'Brien 2007 (1) - 1Dokument22 SeitenO'Brien 2007 (1) - 1Bro BroNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 O Neill Anxiety and Depression Symptomatology in Adult Siblings of Individuals With Different Developmental Disability DiagnosesDokument10 Seiten2016 O Neill Anxiety and Depression Symptomatology in Adult Siblings of Individuals With Different Developmental Disability Diagnosesnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- Meta-Analysis of Comparative Studies of Depression in Mothers of Children With and Without Developmental DisabilitiesDokument15 SeitenMeta-Analysis of Comparative Studies of Depression in Mothers of Children With and Without Developmental DisabilitiesLudmila MenezesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sibling Influences On Theory of Mind Development For Children With ASDDokument7 SeitenSibling Influences On Theory of Mind Development For Children With ASDAnonymous 75M6uB3Ow100% (1)

- Adjustment, Sibling Problems and Coping Strategies of Brothers and Sisters of Children With Autistic Spectrum DisorderDokument11 SeitenAdjustment, Sibling Problems and Coping Strategies of Brothers and Sisters of Children With Autistic Spectrum DisorderkatanitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Content ServerDokument13 SeitenContent ServerMelindaDuciagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parents of Adults With An Intellectual Disability: Monica CuskellyDokument6 SeitenParents of Adults With An Intellectual Disability: Monica CuskellyShirley ChavarríaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0 RIA Parents and Professional ViewsDokument11 Seiten0 RIA Parents and Professional ViewsAncuța IfteneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Template - Artikel 1 - No Absen 1 S.D 8Dokument12 SeitenTemplate - Artikel 1 - No Absen 1 S.D 8Angelica EarlyanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adams - 2018 - Well-Being in Mothers of Children With Rare Genetic SyndromesDokument13 SeitenAdams - 2018 - Well-Being in Mothers of Children With Rare Genetic SyndromesPetrutaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Conflict Impacts Autism SymptomsDokument14 SeitenFamily Conflict Impacts Autism SymptomslboninsouzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Down Syndrome Research Paper ThesisDokument4 SeitenDown Syndrome Research Paper Thesisfvg4mn01100% (1)

- Selective Mutism in Children: Comparison To Youths With and Without Anxiety DisordersDokument8 SeitenSelective Mutism in Children: Comparison To Youths With and Without Anxiety DisorderspaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Experiencesof African American Mothers AutismDokument18 SeitenExperiencesof African American Mothers AutismKhafifah MadiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Optimism, Social Support, and Well-Being in Mothers of Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDokument11 SeitenOptimism, Social Support, and Well-Being in Mothers of Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderTThay BBrandNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0891422219300691 MainDokument9 Seiten1 s2.0 S0891422219300691 MainMudassar AzizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Anxiety Disorders: Ann E. Layne, Debra H. Bernat, Andrea M. Victor, Gail A. BernsteinDokument7 SeitenJournal of Anxiety Disorders: Ann E. Layne, Debra H. Bernat, Andrea M. Victor, Gail A. BernsteinMelina Defita SariNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI)Dokument19 SeitenInternational Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI)inventionjournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bartov 2018Dokument12 SeitenBartov 2018Thaís Spall ChaximNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parenting Children with Down Syndrome: Understanding Societal InfluencesDokument10 SeitenParenting Children with Down Syndrome: Understanding Societal InfluencesYulia AfresilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hill 2009Dokument12 SeitenHill 2009Frontier JuniorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mental DisabilitiesDokument11 SeitenMental DisabilitiesKaren IrasemaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GROWING UP WITH GRIEFDokument20 SeitenGROWING UP WITH GRIEFfernandamancilhapsiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ASD Parent Stress Article 2004Dokument12 SeitenASD Parent Stress Article 2004DhEg LieShh WowhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emotion Knowledge in Young Neglected Children: Margaret W. SullivanDokument6 SeitenEmotion Knowledge in Young Neglected Children: Margaret W. SullivanditeABCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Issues in The Social and Emotional Adjustment of Gifted ChildrenDokument12 SeitenIssues in The Social and Emotional Adjustment of Gifted Childrenapi-301904910Noch keine Bewertungen

- Annotated BibliographyDokument3 SeitenAnnotated Bibliographyapi-469841810Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1.parental DepressionDokument17 Seiten1.parental DepressionSeby NurakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attachment Theory in Adolescence and AdulthoodDokument6 SeitenAttachment Theory in Adolescence and AdulthoodsimuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Những tác động trong cuộc sống của việc nuôi dạy con cái khuyết tậtDokument22 SeitenNhững tác động trong cuộc sống của việc nuôi dạy con cái khuyết tậtDo ThuyNoch keine Bewertungen

- PocinhoDokument10 SeitenPocinhoriris nurhanifiyantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wiley Society For Research in Child DevelopmentDokument17 SeitenWiley Society For Research in Child DevelopmentXiao CiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MulliganDokument21 SeitenMulliganJG Du PlessisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Representations of The Caregiver-Child Relationship and of The Self, and Emotion Regulation in The Narratives of Young Children Whose Mothers Have BPDDokument20 SeitenRepresentations of The Caregiver-Child Relationship and of The Self, and Emotion Regulation in The Narratives of Young Children Whose Mothers Have BPDme13Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hope and Worry AutismDokument7 SeitenHope and Worry Autismapi-87092797Noch keine Bewertungen

- Maladaptive Behavior Down Syndrome PDFDokument10 SeitenMaladaptive Behavior Down Syndrome PDFsimplerain17893Noch keine Bewertungen

- Resilience in Family Members of Persons With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review of The LiteratureDokument8 SeitenResilience in Family Members of Persons With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review of The Literatureana lara SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mother-Child Relationships, Family Context, and Child Characteristics As Predictors of Anxiety Symptoms in Middle ChildhoodDokument13 SeitenMother-Child Relationships, Family Context, and Child Characteristics As Predictors of Anxiety Symptoms in Middle ChildhoodNina GarfoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CORSANO-Typically Developing Adolescents' Experience of Growing Up With A Brother With An Autism Spectrum DisorderDokument12 SeitenCORSANO-Typically Developing Adolescents' Experience of Growing Up With A Brother With An Autism Spectrum DisorderwNoch keine Bewertungen

- Articole Stiintifice PsihologieDokument10 SeitenArticole Stiintifice PsihologieMircea RaduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Predictors of Parental Stress in Mothers of Young Children With Hearing LossDokument17 SeitenPredictors of Parental Stress in Mothers of Young Children With Hearing LossPija RamliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Families of Children With Down Syndrome What We KNDokument10 SeitenFamilies of Children With Down Syndrome What We KNroneldayo62Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mental Health of Transgender ChildrenDokument10 SeitenMental Health of Transgender ChildrenMarian Mario SpagnuoloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rogers 2003Dokument12 SeitenRogers 2003dimasprastiiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poverty and BrainDokument24 SeitenPoverty and BrainManuel Guerrero GómezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Falsas DenunciasDokument22 SeitenFalsas DenunciasmayeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Children in Foster Care: A Vulnerable Population at Risk: Delilah Bruskas, RN, MNDokument8 SeitenChildren in Foster Care: A Vulnerable Population at Risk: Delilah Bruskas, RN, MNMohamed AbdulqadirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anxiety Levels in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder A Meta AnalysisDokument15 SeitenAnxiety Levels in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder A Meta AnalysisvaishnaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Content ServerDokument18 SeitenContent ServerMelindaDuciagNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Adjustment of Nondisabled Adolescent Siblings of Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorder in The HomeDokument18 SeitenThe Adjustment of Nondisabled Adolescent Siblings of Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorder in The HomeAutism Society Philippines100% (4)

- Families of Children With Rett Syndrome PDFDokument17 SeitenFamilies of Children With Rett Syndrome PDFOtono ExtranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2004 Psychosocial Determinants of Behaviour ProblemsDokument10 Seiten2004 Psychosocial Determinants of Behaviour ProblemsMariajosé CaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joint Attention and Disorganized Attachment Status in Infants at RiskDokument14 SeitenJoint Attention and Disorganized Attachment Status in Infants at RiskCarolina Saavedra MellaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Workings of The Lit ReviewDokument24 SeitenWorkings of The Lit Reviewapi-299743021Noch keine Bewertungen

- Responses To The Negative Emotions of Others by Autistic, Mentally Retarded, and Normal ChildrenDokument13 SeitenResponses To The Negative Emotions of Others by Autistic, Mentally Retarded, and Normal ChildrenBIANA-MARIA MACOVEINoch keine Bewertungen

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDokument9 SeitenNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDanielaLealNoch keine Bewertungen

- nuttall2018Dokument11 Seitennuttall2018Réka SnakóczkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Support, Communication, and Hardiness in Families With Children With DisabilitiesDokument17 SeitenSupport, Communication, and Hardiness in Families With Children With DisabilitiesAnnisa Dwi NoviantyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edtpa 2nd Lesson PlanDokument5 SeitenEdtpa 2nd Lesson Planapi-297045693Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ward Security Application Form Nov 2011Dokument14 SeitenWard Security Application Form Nov 2011Wajid Iqbal100% (1)

- Educating Learners Chapter 9Dokument50 SeitenEducating Learners Chapter 9Allyssa Lorraine PrudencioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roles Functions Advice NoteDokument27 SeitenRoles Functions Advice NoteCristina Lorena Grasu100% (1)

- Cesc 12 - Q1 - M17Dokument14 SeitenCesc 12 - Q1 - M17jayson babaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- M30 Reinforced Concrete Column Design DetailsDokument1 SeiteM30 Reinforced Concrete Column Design DetailsCMM INFRAPROJECTS LTDNoch keine Bewertungen

- GESP FORMS With Suggested Movs For DRRMDokument64 SeitenGESP FORMS With Suggested Movs For DRRMEnen DagumampanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mental Health Care and Human Rights - NHRC IndiaDokument472 SeitenMental Health Care and Human Rights - NHRC IndiaVaishnavi JayakumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sexuality Re MasturbationDokument17 SeitenSexuality Re MasturbationMaria AlvanouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demons of The Body and MindDokument245 SeitenDemons of The Body and MindPerekatypole100% (5)

- Final ProjectDokument27 SeitenFinal Projectapi-284802869Noch keine Bewertungen

- PTSDDokument30 SeitenPTSDVohn Andrae SarmientoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Work History Report SSA-3369-BKDokument10 SeitenWork History Report SSA-3369-BKLevine BenjaminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Task 3 - Special EducationDokument3 SeitenTask 3 - Special EducationShainna BaloteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment - Inclusive EducationDokument13 SeitenAssignment - Inclusive Educationapi-357686594Noch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis ReportDokument11 SeitenThesis ReportPooja Sharma100% (2)

- Physical Disabilities Reflection No. 8Dokument3 SeitenPhysical Disabilities Reflection No. 8Carlo TunongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Efficacy Managing Preschool Behavior ChallengesDokument12 SeitenTeacher Efficacy Managing Preschool Behavior ChallengesAnonymous TLQn9SoRRbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bipolar Disorder: Causes, Symptoms and Famous FiguresDokument54 SeitenBipolar Disorder: Causes, Symptoms and Famous Figuresleanne yangNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Schizophrenia AssessmentDokument36 Seiten3 Schizophrenia AssessmentArvindhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Studies in Social Enterprise: Counterpart International's ExperienceDokument59 SeitenCase Studies in Social Enterprise: Counterpart International's ExperienceRozina ImtiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 - 50 Ways Bias Fundamentals - English - v1 CompressedDokument67 Seiten1 - 50 Ways Bias Fundamentals - English - v1 CompressedMaryReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accessibility For Disabled in Public TransportatioDokument9 SeitenAccessibility For Disabled in Public TransportatioIrfan Nurfauzan IskandarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crtique On Finland SPEDDokument10 SeitenCrtique On Finland SPEDErvin SalupareNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developmental Disabilities and Their Management / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental AcademyDokument71 SeitenDevelopmental Disabilities and Their Management / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental Academyindian dental academyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Brain: Understanding Psychological Disorders Through NeuroimagingDokument14 SeitenThe Brain: Understanding Psychological Disorders Through NeuroimagingSiti SarahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disability World 25Dokument264 SeitenDisability World 25Ezekiel T. MostieroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schizophrenia in Old AgeDokument21 SeitenSchizophrenia in Old AgeAyedh TalhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICF-Curriculum Modules v1 Approved FINAL 1Dokument12 SeitenICF-Curriculum Modules v1 Approved FINAL 1HariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fabric Cutter Amh q1510 v1.0Dokument31 SeitenFabric Cutter Amh q1510 v1.0Puneet KaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesVon EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (70)

- The Somatic Psychotherapy Toolbox: A Comprehensive Guide to Healing Trauma and StressVon EverandThe Somatic Psychotherapy Toolbox: A Comprehensive Guide to Healing Trauma and StressNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryVon EverandRewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (157)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingVon EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Feel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LoveVon EverandFeel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LoveBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (249)

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsVon EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (38)

- The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandThe Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (2)

- The Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeVon EverandThe Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (140)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyVon EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Summary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDVon EverandSummary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (167)

- Rapid Weight Loss Hypnosis: How to Lose Weight with Self-Hypnosis, Positive Affirmations, Guided Meditations, and Hypnotherapy to Stop Emotional Eating, Food Addiction, Binge Eating and MoreVon EverandRapid Weight Loss Hypnosis: How to Lose Weight with Self-Hypnosis, Positive Affirmations, Guided Meditations, and Hypnotherapy to Stop Emotional Eating, Food Addiction, Binge Eating and MoreBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (17)

- Fighting Words Devotional: 100 Days of Speaking Truth into the DarknessVon EverandFighting Words Devotional: 100 Days of Speaking Truth into the DarknessBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (6)

- BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER: Help Yourself and Help Others. Articulate Guide to BPD. Tools and Techniques to Control Emotions, Anger, and Mood Swings. Save All Your Relationships and Yourself. NEW VERSIONVon EverandBORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER: Help Yourself and Help Others. Articulate Guide to BPD. Tools and Techniques to Control Emotions, Anger, and Mood Swings. Save All Your Relationships and Yourself. NEW VERSIONBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (24)

- Winning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeVon EverandWinning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (553)

- Heal the Body, Heal the Mind: A Somatic Approach to Moving Beyond TraumaVon EverandHeal the Body, Heal the Mind: A Somatic Approach to Moving Beyond TraumaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (56)

- Overcoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts: A CBT-Based Guide to Getting Over Frightening, Obsessive, or Disturbing ThoughtsVon EverandOvercoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts: A CBT-Based Guide to Getting Over Frightening, Obsessive, or Disturbing ThoughtsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (48)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (9)

- Somatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionVon EverandSomatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Autoimmune Cure: Healing the Trauma and Other Triggers That Have Turned Your Body Against YouVon EverandThe Autoimmune Cure: Healing the Trauma and Other Triggers That Have Turned Your Body Against YouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Insecure in Love: How Anxious Attachment Can Make You Feel Jealous, Needy, and Worried and What You Can Do About ItVon EverandInsecure in Love: How Anxious Attachment Can Make You Feel Jealous, Needy, and Worried and What You Can Do About ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (84)

- Emotional Detox for Anxiety: 7 Steps to Release Anxiety and Energize JoyVon EverandEmotional Detox for Anxiety: 7 Steps to Release Anxiety and Energize JoyBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (6)

- Smart Phone Dumb Phone: Free Yourself from Digital AddictionVon EverandSmart Phone Dumb Phone: Free Yourself from Digital AddictionBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (11)

- Triggers: How We Can Stop Reacting and Start HealingVon EverandTriggers: How We Can Stop Reacting and Start HealingBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (57)

- The Anxiety Healer's Guide: Coping Strategies and Mindfulness Techniques to Calm the Mind and BodyVon EverandThe Anxiety Healer's Guide: Coping Strategies and Mindfulness Techniques to Calm the Mind and BodyNoch keine Bewertungen