Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Emporium Strikes Back

Hochgeladen von

GuenazOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Emporium Strikes Back

Hochgeladen von

GuenazCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The emporium strikes back https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21581755-retailers-ri...

Shopping

The emporium strikes back

Retailers in the rich world are suffering as people buy more things online. But they are

finding ways to adapt

Print edition | Brieng Jul 13th 2013

THE staff at Jessops would like to thank you for shopping with Amazon. With that

parting shot plastered to the front door of one of its shops, a company that had

been selling cameras in Britain for 78 years shut down in January. The bitter note

sums up the mood of many who work on high streets and in shopping centres

(malls) across Europe and America. As sales migrate to Amazon and other online

vendors, shop after shop is closing down, chain after chain is cutting back. Borders,

a chain of American bookshops, is gone. So is Comet, a British white-goods and

electronics retailer. Virgin Megastores have vanished from France, Tower Records

1 von 10 10.09.17, 18:50

The emporium strikes back https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21581755-retailers-ri...

from America. In just two weeks in June and July, five retail chains with a total

turnover of 600m ($900m) failed in Britain.

Watching the destruction, it is tempting to conclude that shops are to shopping

what typewriters are to writing: an old technology doomed by a better successor.

Seattle-based Amazon, nearing its 19th birthday, has lower costs than the vast

majority of bricks-and-mortar retailers. However many shops, of whatever

remarkable hypersize, a company builds in the attempt to offer vast choice at low

prices, the internet is vaster and cheaper. Prosperous Londoners and New Yorkers

ask themselves when was the last time they went shopping; their shopping comes

to them. Retail guys are going to go out of business and e-commerce will become

the place everyone buys, pronounces Marc Andreessen, a celebrity venture

capitalist. You are not going to have a choice.

Online

Latest updates

commerce

Will credit cause a slowdown?

BUTTONWOODS NOTEBOOK has grown

Abraham's story shows the similarities and the at different

dierences between faiths

rates in

ERASMUS

different

Russia votes, but will the Kremlin notice?

EUROPE countries,

but

See all updates

everywhere

it is gaining fast (see chart 1). In Britain, Germany

and France 90% of the rather modest growth in

retail sales expected between now and 2016 will be online, predicts AXA Real Estate,

a property-management company.

Old dog, meet new tricks

This would hurt less if shoppers were spending more; smaller slices are more

acceptable when they come from bigger pies. But in many rich countries, especially

in Europe, consumers are still smarting from the bursting of the credit bubble and

high unemployment. American consumers are perkier, but seem to be clinging to

the bargain-hunting habits of the recession. Services have been consuming a bigger

2 von 10 10.09.17, 18:50

The emporium strikes back https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21581755-retailers-ri...

share of their wallets for decades, leaving less to

spend on things (see chart 2). Ageing populations

could shrink the pie further. Old people shop less.

When shoppers both know what they want and are

willing to wait for it they will go online. And retails

simple moneymaking ways of yesteryearfind a

catchy concept, fuel growth by opening new shops

and attracting more shoppers to existing ones, use

your growing size to squeeze suppliers for better

marginshave run out of steam. But that does not

mean that there are no new options for bricks and mortar.

Shopping is about entertainment as well as acquisition. It allows people to build

desires as well as fulfil themif it did not, no one would ever window-shop. It

encompasses exploration and frivolity, not just necessity. It can be immersive, too.

While computer screens can bewitch the eye, a good shop has four more senses to

ensorcell. No one makes the point better than Apple; in terms of sales per unit area

its showrooms-slash-playrooms best all other American retailers.

And shops make money. Bricks-and-mortar retail may be losing ground to online

shopping, but it remains more profitable. The physical world is also increasingly

capable of taking the fight to its online competitors. Last year online sales of shop-

based American retailers grew by 29%; those of online-only merchants grew by just

21%. Apart from Amazonwhich has long spurned profits in favour of growth

most pure-play online retailers are losing market share, says Sucharita Mulpuru of

Forrester Research. The bricks-and-mortar retrenchment will be painful, but the

survivors may make shopping a less formulaic, more satisfying and possibly even

more profitable experience, both offline and on.

Many brands still think shops are the best way to attract customers. Inditex of

Spain, owner of the ubiquitous Zara fashion brand, opened 482 stores in 2012,

bringing its total to 6,009 in 86 countries. Primark, a fast-growing vendor of nearly

disposable clothing, sells nothing on its website, relying on its 242 shops for

almost all its sales. The same can hold at the luxury end, toofew will buy a

3 von 10 10.09.17, 18:50

The emporium strikes back https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21581755-retailers-ri...

$10,000 necklace online, or entrust it to the post. Space on the snazziest streets in

London, Paris and New York is in such demand that luxury retailers pay millions in

key money to secure it, says Mark Burlton of Cushman & Wakefield, a property

company.

Offline-only, though, is a shrinking category. Now that the initial shock of the

online onslaught has worn off, most big retailers have joined it. They proclaim

themselves to be omnichannel merchants, as adept as Amazon online but with

the added excitement and convenience that comes with physical shops. Philip

Clarke, chief executive of Tesco, Britains largest retailer, says that app development

will come to be as important to his company as property development. Walmart,

the worlds biggest retailer, has 1,500 employees in Silicon Valley trying to out-

Amazon Amazon in areas such as logistics and making the most of social media.

Some online natives are going omnichannel, too. Pace Mr Andreessen, New York-

based Warby Parker, which sells trendy spectacles at prices lower than those

charged by famous brands, has opened 14 shops, one of them a school bus that

tours the country. Some potential customers were wary of buying spectacles from

an online-only merchant. We thought bricks and mortar would bring gravitas to

the brand, says Neil Blumenthal, a co-founder. Its SoHo flagship resembles a

library. Appointments with the in-store optometrist are displayed on a railway-

station-style time board.

Currying favour

Britain may be one of the places where the future of retail is most easily seen.

Online shopping has advanced further there than in other developed economies.

The population is quite tightly packed, which makes delivery relatively cheap, and

70% have broadband internet access. It is one of the few places where online

grocery shopping has taken off. Eventually, predicts Panmure Gordon, an

investment bank, 20% of the food business will be online. For non-food items it

will average 40%, but there will be a large range. For entertainment it may be 90%;

for DIY supplies as little as 15%.

Footfall on British high streets has declined for seven years running. Citi Research,

part of Citigroup, a bank, calculates that comparable sales at a representative

4 von 10 10.09.17, 18:50

The emporium strikes back https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21581755-retailers-ri...

selection of Britains clothing chains fell by 3-5% a year between 2009 and 2012.

Shop rents are high and leases are long, which piles on the pressure. Vacancy rates

have risen fivefold to 14% since 2008. A report by the Centre for Retail Research

predicts that a fifth of Britains high-street shops will close over the next five years,

eliminating more than 300,000 jobs.

Britains brick-burdened retailers may be heartened, though, by the example of

Dixons Retail, owner of Britains biggest electronics and computer retailers, Currys

and PC World, and of similar chains in other countries. Between 15% and 20% of

sales at Dixons are online, depending on the season, and the proportion is rising.

But Dixons thinks the advantages which online-only merchants get by doing away

with shops and sales staff are undercut by the need to pay more than high-street

shops do to acquire customers (largely by paying Google for clicks on adverts) and

to spend a lot on shipping. So instead of doing away with shops and sales staff,

Dixons is trying to get more out of them.

Shoppers may be tempted to treat electronics stores as showrooms for Amazon and

its like, but at least they cross a retailers threshold at some point during their quest

90% of the time, notes Dixons boss, Sebastian Jamesand with rivals like Comet

having closed down, that threshold is ever more likely to be Dixons. This gives the

company the means to procure better terms than online rivals do from its

suppliers, which like the idea of customers actually seeing their wares in the flesh,

shown off by flesh-and-blood people. Sometimes, as with a recent AEG washing

machine and Samsung camera, Dixons enjoys a period of exclusivity.

Thus peoples tendency to use the shops as showrooms is turned, at least in part, to

the companys advantage. Other retailers are seeking to embrace the practice too.

Best Buy, Americas biggest electronics retailer, used to cover up barcodes to stop

shoppers from using their phones to compare prices. Today the retailers new boss,

Hubert Joly, professes to love showrooming because it means that a prospective

customer is on the premises.

Having people on the premises also helps Dixons to bundle salesin particular, to

sell high-margin accessories and services along with low-margin devices. Mr James

says that computers in Dixons were 26% more expensive than on Amazon three

5 von 10 10.09.17, 18:50

The emporium strikes back https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21581755-retailers-ri...

years ago. Now the difference is pretty much zero. So the shops must make money

by selling the world that goes around the productlike a computer bag or high

quality cables.

These stratagems depend on having attractive stores and able shop assistants.

Dixons has retrained its staff and changed their incentives. Individual sales

commissions have been scrapped in favour of store-wide schemes linked to

measures of customer satisfaction. To overcome managers reluctance to refer

customers to the website, stores are now credited with all sales in their catchment

area, regardless of whether a buyer entered the premises.

The omnichannellers dilemma

But though owning shops is basic to Dixons strategy, the number of shops is

dropping, and will drop further. Dixons has cut its British network from 780 to 486;

it aims to end up with just under 400. Jessops, which has been reopened after

shedding more than 80% of its stores by Peter Jones, a flamboyant reality-television

entrepreneur, is making a similar bet.

For many retailers, such reductions are an inescapable part of going omnichannel.

Youre putting in more capital to keep the sales you have, says Colin McGranahan

of Sanford C. Bernstein, a research firm. Investment which used to go mainly into

new stores must now in part be redirected towards the technology and distribution

that online sales require. And sales through new channels come in part at the

expense of existing shops, the costs of which are largely fixed. That depresses the

retailers profits and forces it to close shops.

Other sectors have some advantages over electronics and camera sales. It is not so

easy for shoppers to use food and clothing shopsboth of which are big parts of

retailas showrooms for online sales. You cannot squeeze a melon with a tablet

computer; phones make poor fitting rooms.

For online-only retailers such products cause extra headaches. Clothes shoppers

return a quarter or more of the garments they buy. Selling groceries online is

laborious, with lots of low-value items stored at different temperatures that have to

be assembled into all manner of unique orders and then delivered rapidly.

6 von 10 10.09.17, 18:50

The emporium strikes back https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21581755-retailers-ri...

But online-only retailers keep inventing clever ways to overcome such disabilities.

Amazons subscribe and save service delivers at regular intervals staple products

like nappies and coffee. Fits.me sets up virtual fitting rooms for online clothiers,

which let shoppers enter their measurements to see how garments would look on

them. Citi Research expects British online clothing sales to double in the next six

years. There are no glass ceilings on any particular category, says Robin Terrell,

head of Tescos online business.

For Tesco, the worlds third-biggest retailer, the challenge of mastering online

grocery while shoring up its traditional business is acute. The company outsells all

other British grocers on the internet; but its market share has been slipping both

online and off and a recent poll rated its shops lower in quality than those of any

other British grocer. Like Carrefour, the French firm that is retails global number

two, Tesco has pulled back from some attempts to expand internationally in order

to win back lost ground at home.

Change in store

Around 40% of Tescos British floorspace is in hypermarkets which seem ill suited

to new trends, based as they partly are on the idea of selling things that people

would rather buy online, such as televisions, alongside food. The Institute of

Grocery Distribution, an industry think-tank, sees sales in Britains big shops

growing by just 6.4% between 2012 and 2017. The growth that is not found online is

going to come from neighbourhood convenience shops, which the institute sees as

growing by 28.5% over the same time. So that is where Tesco, like Carrefour and

Walmart elsewhere, is heading. In April Tesco took an 804m write down on the

value of its British property as it scaled back plans for future big supermarkets.

After a decade spent bringing its shops online Tesco now sees it as time to bring

the internet into stores, says Mike McNamara, the companys technology chief.

The idea is that this will make shops both more productive and more popular.

Tescos in-store cafs could have interactive tabletops, which, prompted by a

customers cellphone, would suggest recipes based on his shopping list. Similar

wizardry could tell staff which fruit and vegetables need replenishment. The

hypermarkets will also sell more clothing and cosmetics, which have higher

margins than electronics and seem a more natural fit with food.

7 von 10 10.09.17, 18:50

The emporium strikes back https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21581755-retailers-ri...

Online sales are the fastest-growing part of Tescos

business, but analysts doubt they bring much

profit. On a fully costed basis no one makes

money in online grocery, says Andrew Gwynn of

Exane, an investment company. But online offers a

real advantage in serving Tescos most loyal and

profitable customers. Tesco has been hoovering up

information through its Clubcard loyalty scheme

for years; computers can take that further. We are

teetering on the brink of an era of mass

personalisation, says the retailers boss, Mr Clarke.

Loyal customers are worth far more to Tesco than

footloose ones.

Deep personalisation could have disruptive consequences. Retailers are beginning

to see profit per household, rather than per square metre, as the thing they should

target, according to the Boston Consulting Group. Safeway, an American

supermarket, offers individualised pricing through its just for u loyalty scheme.

Mr Clarke seems wary. Tesco should be classless, he says, meaning it should not

discriminate among its customers. But the temptation will be there. Tesco still uses

traditional yardsticks but customer-level metrics will challenge the way the

company thinks, says Mr Terrell.

Many chains are going through similar change, looking again at every aspect of

their logistics (a 95% accuracy rate is acceptable for shipments to grocery shops but

anything short of 100% risks turning off a customer), their staff training, the

number, size and location of their shops and what they offer the customer. Asda, a

competitor to Tesco in Britain that is owned by Walmart, is transforming big

supermarkets into mini high streets, bringing in Disney shops and shoe repairs

(Tesco has bought Giraffe, a restaurant chain, for similar purposes). John Lewis, a

British omnichannel role model, takes the view that targeting individual shoppers

rather than single channels is the way to profitability. Click and collect services

let shoppers pick up online purchases at a convenient store where they might also

buy something else.

8 von 10 10.09.17, 18:50

The emporium strikes back https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21581755-retailers-ri...

The future shopscape will be emptier, but more attractive. Shoppers can expect new

rewards for simply showing up. Shopkick, a mobile-phone app, gives American

shoppers points that earn them goodies like iTunes songs just for stepping across

the threshold of a participating store. Inspired by Apple, shops promise

experience and hope that sales will follow. Germanys Kochhaus claims to be the

first food store organised around recipes rather than grocery categories. The

ingredients are strewn across tables, not stacked on shelves. Some shops will opt to

sell nothing at all on the premises. Desigual, a Spanish fashion merchant, has

shops in Barcelona and Paris that carry only samples. Shoppers are helped to

assemble them into outfits that they then buy online.

Shopping centres are reallocating space from the classic form of retailing to leisure

and entertainment. In Britain the non-retail share of shopping-centre revenue has

risen from the 5% once seen as standard to 10-15% and could rise to 20% over the

next five years, says the British Council of Shopping Centres. The same trend holds

across much of Europe. In America nearly a quarter of the space in shopping

centres is occupied by businesses other than shops and restaurants. Medical

services may become principal attractions, says Michael Niemira of the

International Council of Shopping Centres. Health care accounts for just 1% of

space now but Mr Niemira and others expect it to explode.

Room for improvement

Nothing is settled. The bundles assembled by Dixons and its kind may be brutally

unpicked by online competitors. A logistical arms race is heating up. Amazon,

having given up its resistance to collecting state sales tax in America, is building

fulfilment centres near cities to speed delivery. Bricks-and-mortar shops are

striking back with services such as Shutl, which arranges fast home deliveries from

store networks. And all retailers are competing increasingly with suppliers seeking

new direct routes to market. Last year online sales by companies that make their

own products grew faster than those of both shops and online-only retailers in

America.

And new hybrids are emerging. Yihaodian, a Chinese company owned by Walmart,

has used an app to let phone users visit 1,000 virtual stores accessible only at

specific sitesmany of which, rather cheekily, were on the doorsteps of rival

9 von 10 10.09.17, 18:50

The emporium strikes back https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21581755-retailers-ri...

retailers. Tescos Korean subsidiary, Homeplus, puts up images of products on

posters in the subway; commuters can scan them to get the products delivered.

Tangible and virtual retailing may meld in all sorts of unaccustomed ways. Even

Amazon has flirted with the idea of opening physical stores. Consumers have

reason to cheer the survival of the sexiest.

Youve seen the news,

now discover the story

Get incisive analysis on the issues that

matter. Whether you read each issue cover

to cover, listen to the audio edition, or scan

the headlines on your phone, time with

The Economist is always well spent.

Enjoy 12 weeks access for 20

10 von 10 10.09.17, 18:50

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Retail Recovery: How Creative Retailers Are Winning in their Post-Apocalyptic WorldVon EverandRetail Recovery: How Creative Retailers Are Winning in their Post-Apocalyptic WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emporium Strikes Back - Economist 2013Dokument8 SeitenThe Emporium Strikes Back - Economist 2013Jorge Humberto Chambi VillarroelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shopping: The Emporium Strikes Back - The EconomistDokument12 SeitenShopping: The Emporium Strikes Back - The EconomistmottebossNoch keine Bewertungen

- The E-Commerce Book: About a channel that became an industryVon EverandThe E-Commerce Book: About a channel that became an industryNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Rise of The Rebel BrandsDokument4 SeitenThe Rise of The Rebel BrandsNoa GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- e-Commerce: An e-Book Special ReportVon Everande-Commerce: An e-Book Special ReportBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- E-Commerce Takes Off - The New BazaarDokument5 SeitenE-Commerce Takes Off - The New BazaarTon ToniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Retail Therapy: Why The Retail Industry Is Broken – And What Can Be Done To Fix ItVon EverandRetail Therapy: Why The Retail Industry Is Broken – And What Can Be Done To Fix ItNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Great Retail Apocalypse of 2017 - The Atlantic PDFDokument9 SeitenThe Great Retail Apocalypse of 2017 - The Atlantic PDFlimyisyuenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resurrecting Retail: The Future of Business in a Post-Pandemic WorldVon EverandResurrecting Retail: The Future of Business in a Post-Pandemic WorldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Innovation in Retail 2019Dokument30 SeitenInnovation in Retail 2019mystratexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is It The End of The Physical Stores 1663160910Dokument10 SeitenIs It The End of The Physical Stores 1663160910Ashick AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Can CRM Save The Brick-and-Mortar Folks?: Sno Abo S C o o H D P Duc SDokument11 SeitenCan CRM Save The Brick-and-Mortar Folks?: Sno Abo S C o o H D P Duc SkhairinafitriiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commercial DarwinismDokument13 SeitenCommercial DarwinismSteven BudzinskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Retail - A Tale As Old As Time: Looking Back, But Moving ForwardDokument5 SeitenRetail - A Tale As Old As Time: Looking Back, But Moving ForwardCatalinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2015 OliverWyman Online Retail Report PDFDokument43 Seiten2015 OliverWyman Online Retail Report PDFNishith NegandhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Decline of SupermarketsDokument2 SeitenThe Decline of SupermarketsLucas BettonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Future of Grocery in Digital WorldDokument70 SeitenFuture of Grocery in Digital WorldgeniusMAHINoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To E-Commerce: 1 A Perfect MarketDokument20 SeitenIntroduction To E-Commerce: 1 A Perfect MarketTudorNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIS16 CH10 Case1 Walmart-v-AmazonDokument3 SeitenMIS16 CH10 Case1 Walmart-v-AmazonMuhammad Ali Hassan BhattiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amazon Fresh - Shoppers Give Verdict On Futuristic Till-Free Supermarket - The IndependentDokument11 SeitenAmazon Fresh - Shoppers Give Verdict On Futuristic Till-Free Supermarket - The IndependentIan SecretariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brand Loyalty Is Not Dead, Brand Loyalty Is All About The Customers' Emotions andDokument6 SeitenBrand Loyalty Is Not Dead, Brand Loyalty Is All About The Customers' Emotions andLorraine CalvoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Watch The You Tube The Link Given To YouDokument2 SeitenWatch The You Tube The Link Given To YouKho, JasminNoch keine Bewertungen

- 中-英 电商Dokument4 Seiten中-英 电商414131221Noch keine Bewertungen

- Omnichannel Supply Chain in FocusDokument17 SeitenOmnichannel Supply Chain in FocusalejandrosantizoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Future of Retailing - ReportDokument45 SeitenThe Future of Retailing - ReportcyrutNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amazon Has Just Shown Off The Most Advanced Technology StoreDokument3 SeitenAmazon Has Just Shown Off The Most Advanced Technology StoreEmanuel VasconcelosNoch keine Bewertungen

- NH English Reading For Understanding Analysis and Evaluation Text 2021Dokument6 SeitenNH English Reading For Understanding Analysis and Evaluation Text 2021sh5d6xqxhhNoch keine Bewertungen

- BUSM1100 Major Team Assignment Rough Draft - Group 1Dokument8 SeitenBUSM1100 Major Team Assignment Rough Draft - Group 1Rupinder jeet kaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amazon & WalmartDokument27 SeitenAmazon & WalmartJesus Andrade100% (1)

- Retail Supply Chains Have Been Disrupted by The Rise of New Distribution and Fulfillment ChannelsDokument32 SeitenRetail Supply Chains Have Been Disrupted by The Rise of New Distribution and Fulfillment ChannelsPeter MulwaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rukmini Devi Institute of Advanced StudiesDokument50 SeitenRukmini Devi Institute of Advanced StudiesMicky GautamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Walmart and Amazon Duke It Out For E-Commerce Supremacy Case StudyDokument7 SeitenWalmart and Amazon Duke It Out For E-Commerce Supremacy Case StudyJozetta Amaril Avenia RosavenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How The Internet Impacts On Brand ManagementDokument3 SeitenHow The Internet Impacts On Brand Managementalberto.toppinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- TP03. Amazon Go - U6Dokument3 SeitenTP03. Amazon Go - U6Mademoiselle HugNoch keine Bewertungen

- Retail Reinvention Day 1 Recap: Consumer Experience Takes Centre StageDokument3 SeitenRetail Reinvention Day 1 Recap: Consumer Experience Takes Centre StageaNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Case 10) Walmart and AmazonDokument7 Seiten(Case 10) Walmart and Amazonberliana setyawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Case 10) Walmart and AmazonDokument7 Seiten(Case 10) Walmart and Amazonberliana setyawatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Walmart - Amazon - E-CommerceDokument3 SeitenCase Walmart - Amazon - E-Commerceken_mjzzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Top 10 E-Commerce Sites in The UK 2020 - DisfoldDokument10 SeitenTop 10 E-Commerce Sites in The UK 2020 - DisfoldFranck MauryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion Retail: New Measures of Success: Getting It Right With Young ConsumersDokument37 SeitenFashion Retail: New Measures of Success: Getting It Right With Young ConsumersAmanda FerreiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ocado CaseDokument18 SeitenOcado CasePedro Surish Zepeda0% (1)

- Amazon SWOTDokument2 SeitenAmazon SWOTLily ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wufc Issue 8 Final 2Dokument6 SeitenWufc Issue 8 Final 2whartonfinanceclubNoch keine Bewertungen

- Walmart An E-Commerce Sleeping Giant Is Waking Up ThehillDokument3 SeitenWalmart An E-Commerce Sleeping Giant Is Waking Up Thehillapi-527494300Noch keine Bewertungen

- Why Retailers Everywhere Should Look To ChinaDokument3 SeitenWhy Retailers Everywhere Should Look To ChinaMaggie PonceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tesco Opens New Dotcom Centre in South East LondonDokument7 SeitenTesco Opens New Dotcom Centre in South East LondonPrashanth RameshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 10 IT Project ReportDokument24 SeitenGroup 10 IT Project Reportabhisht89Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jacob Lucco Synthesis FinDokument5 SeitenJacob Lucco Synthesis Finapi-613055730Noch keine Bewertungen

- Virtually Taking OverDokument3 SeitenVirtually Taking OverAltin KulliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Retail Management JournalDokument86 SeitenRetail Management JournalvanshikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Walmart and Amazon Duke It Out For E-Commerce SupremacyDokument4 SeitenWalmart and Amazon Duke It Out For E-Commerce SupremacyJayson TasarraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manager's Journal: Big Profits Are in Store From The Online RevolutionDokument3 SeitenManager's Journal: Big Profits Are in Store From The Online RevolutionSai PrashantNoch keine Bewertungen

- In This Deep DiveDokument5 SeitenIn This Deep DiveKishan Nagesh ShanbhagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qu NH Cute Phô Mai QueDokument5 SeitenQu NH Cute Phô Mai QueNguyễn QuỳnhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Synthesis Essay Final DraftDokument6 SeitenSynthesis Essay Final Draftapi-575341156Noch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation 1Dokument23 SeitenPresentation 1Mahak SarawagiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment Task 2Dokument7 SeitenAssessment Task 2Lovejinder Singh VirkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engineering Change Notice (Engineering Change Request)Dokument1 SeiteEngineering Change Notice (Engineering Change Request)GuenazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Integrated Marketing Communications: PromotionDokument52 SeitenIntroduction To Integrated Marketing Communications: PromotionGuenazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disney Company AnalysisDokument29 SeitenDisney Company AnalysisGuenazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture Slides Chapter 11Dokument22 SeitenLecture Slides Chapter 11GuenazNoch keine Bewertungen

- 49 - NBM - Freemium ModelDokument16 Seiten49 - NBM - Freemium ModelGuenazNoch keine Bewertungen

- KIT Skript-IntMarketing PDFDokument191 SeitenKIT Skript-IntMarketing PDFGuenazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Marketing Comes of Age A Comprehensive Review of The LiteratureDokument179 SeitenBusiness Marketing Comes of Age A Comprehensive Review of The LiteratureGuenazNoch keine Bewertungen

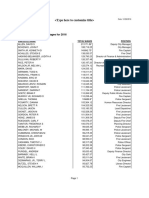

- 2016 W-2 Gross Wages CityDokument16 Seiten2016 W-2 Gross Wages CityportsmouthheraldNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Medium-Rise Residential Building: A B C E D F G HDokument3 SeitenA Medium-Rise Residential Building: A B C E D F G HBabyjhaneTanItmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Union Test Prep Nclex Study GuideDokument115 SeitenUnion Test Prep Nclex Study GuideBradburn Nursing100% (2)

- ResumeDokument3 SeitenResumeapi-280300136Noch keine Bewertungen

- General Chemistry 2 Q1 Lesson 5 Endothermic and Exotheric Reaction and Heating and Cooling CurveDokument19 SeitenGeneral Chemistry 2 Q1 Lesson 5 Endothermic and Exotheric Reaction and Heating and Cooling CurveJolo Allexice R. PinedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HRMDokument118 SeitenHRMKarthic KasiliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Facebook: Daisy BuchananDokument5 SeitenFacebook: Daisy BuchananbelenrichardiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phylogeny Practice ProblemsDokument3 SeitenPhylogeny Practice ProblemsSusan Johnson100% (1)

- Maritta Koch-Weser, Scott Guggenheim - Social Development in The World Bank - Essays in Honor of Michael M. Cernea-Springer (2021)Dokument374 SeitenMaritta Koch-Weser, Scott Guggenheim - Social Development in The World Bank - Essays in Honor of Michael M. Cernea-Springer (2021)IacobNoch keine Bewertungen

- LspciDokument4 SeitenLspciregistroosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Binary OptionsDokument24 SeitenBinary Optionssamsa7Noch keine Bewertungen

- EdisDokument227 SeitenEdisThong Chan100% (1)

- in 30 MinutesDokument5 Seitenin 30 MinutesCésar DiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Hybrid Genetic-Neural Architecture For Stock Indexes ForecastingDokument31 SeitenA Hybrid Genetic-Neural Architecture For Stock Indexes ForecastingMaurizio IdiniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Open Letter To Hon. Nitin Gadkari On Pothole Problem On National and Other Highways in IndiaDokument3 SeitenOpen Letter To Hon. Nitin Gadkari On Pothole Problem On National and Other Highways in IndiaProf. Prithvi Singh KandhalNoch keine Bewertungen

- PP Master Data Version 002Dokument34 SeitenPP Master Data Version 002pranitNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Killer Tips For Transcribing Jazz Solos - Jazz AdviceDokument21 Seiten10 Killer Tips For Transcribing Jazz Solos - Jazz Advicecdmb100% (2)

- Semi Detailed Lesson PlanDokument2 SeitenSemi Detailed Lesson PlanJean-jean Dela Cruz CamatNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 To 20 Years - Girls Stature-For-Age and Weight-For-Age PercentilesDokument1 Seite2 To 20 Years - Girls Stature-For-Age and Weight-For-Age PercentilesRajalakshmi Vengadasamy0% (1)

- Product Manual 26086 (Revision E) : EGCP-2 Engine Generator Control PackageDokument152 SeitenProduct Manual 26086 (Revision E) : EGCP-2 Engine Generator Control PackageErick KurodaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Channels: A Strategic Tool of Growing Importance For The Next MillenniumDokument59 SeitenMarketing Channels: A Strategic Tool of Growing Importance For The Next MillenniumAnonymous ibmeej9Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mathematics Mock Exam 2015Dokument4 SeitenMathematics Mock Exam 2015Ian BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faa Data On B 777 PDFDokument104 SeitenFaa Data On B 777 PDFGurudutt PaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pantalla MTA 100Dokument84 SeitenPantalla MTA 100dariocontrolNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Mane Reason - UNDERSTANDING CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR TOWARDS NATURAL HAIR PRODUCTS IN GHANADokument68 SeitenThe Mane Reason - UNDERSTANDING CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR TOWARDS NATURAL HAIR PRODUCTS IN GHANAYehowadah OddoyeNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Campus of Open Learning) University of Delhi Delhi-110007Dokument1 Seite(Campus of Open Learning) University of Delhi Delhi-110007Sahil Singh RanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Espree I Class Korr3Dokument22 SeitenEspree I Class Korr3hgaucherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pipe Cleaner Lesson PlanDokument2 SeitenPipe Cleaner Lesson PlanTaylor FranklinNoch keine Bewertungen

- AssignmentDokument47 SeitenAssignmentHarrison sajorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bandhan Neft Rtgs FormDokument2 SeitenBandhan Neft Rtgs FormMohit Goyal50% (4)

- The Rape of the Mind: The Psychology of Thought Control, Menticide, and BrainwashingVon EverandThe Rape of the Mind: The Psychology of Thought Control, Menticide, and BrainwashingBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (23)

- The Existential Literature CollectionVon EverandThe Existential Literature CollectionBewertung: 2.5 von 5 Sternen2.5/5 (2)

- $100M Leads: How to Get Strangers to Want to Buy Your StuffVon Everand$100M Leads: How to Get Strangers to Want to Buy Your StuffBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (19)

- The Ultimate Cigar Book: 4th EditionVon EverandThe Ultimate Cigar Book: 4th EditionBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (2)

- SuppressorsVon EverandSuppressorsEditors of RECOIL MagazineNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Wire-Wrapped Jewelry Bible: Artistry Unveiled: Create Stunning Pieces, Master Techniques, and Ignite Your Passion | Include 30+ Wire-Wrapped Jewelry DIY ProjectsVon EverandThe Wire-Wrapped Jewelry Bible: Artistry Unveiled: Create Stunning Pieces, Master Techniques, and Ignite Your Passion | Include 30+ Wire-Wrapped Jewelry DIY ProjectsNoch keine Bewertungen

- How to Trade Gold: Gold Trading Strategies That WorkVon EverandHow to Trade Gold: Gold Trading Strategies That WorkBewertung: 1 von 5 Sternen1/5 (1)

- Amigurumi Made Simple: A Step-By-Step Guide for Trendy Crochet CreationsVon EverandAmigurumi Made Simple: A Step-By-Step Guide for Trendy Crochet CreationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Mary Brooks Picken Method of Modern DressmakingVon EverandThe Mary Brooks Picken Method of Modern DressmakingBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Extreme Bricks: Spectacular, Record-Breaking, and Astounding LEGO Projects from around the WorldVon EverandExtreme Bricks: Spectacular, Record-Breaking, and Astounding LEGO Projects from around the WorldBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (9)

- Advanced Gunsmithing: A Manual of Instruction in the Manufacture, Alteration, and Repair of Firearms (75th Anniversary Edition)Von EverandAdvanced Gunsmithing: A Manual of Instruction in the Manufacture, Alteration, and Repair of Firearms (75th Anniversary Edition)Bewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- Masterpieces of Women's Costume of the 18th and 19th CenturiesVon EverandMasterpieces of Women's Costume of the 18th and 19th CenturiesBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (5)

- Tactical Gun Digest: The World's Greatest Tactical Firearm and Gear BookVon EverandTactical Gun Digest: The World's Greatest Tactical Firearm and Gear BookBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- The Woodcut Artist's Handbook: Techniques and Tools for Relief PrintmakingVon EverandThe Woodcut Artist's Handbook: Techniques and Tools for Relief PrintmakingBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (6)

- I'd Rather Be Reading: A Library of Art for Book LoversVon EverandI'd Rather Be Reading: A Library of Art for Book LoversBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (57)

- A Man and His Mountain: The Everyman Who Created Kendall-Jackson and Became America's Greatest Wine EntrepreneurVon EverandA Man and His Mountain: The Everyman Who Created Kendall-Jackson and Became America's Greatest Wine EntrepreneurBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (10)

- Wrist Watches Explained: How to fully appreciate one of the most complex machine ever inventedVon EverandWrist Watches Explained: How to fully appreciate one of the most complex machine ever inventedBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (3)

- Classic Car Museum Guide: Motor Cars, Motorcycles & MachineryVon EverandClassic Car Museum Guide: Motor Cars, Motorcycles & MachineryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gem Identification Made Easy (4th Edition): A Hands-On Guide to More Confident Buying & SellingVon EverandGem Identification Made Easy (4th Edition): A Hands-On Guide to More Confident Buying & SellingBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- World of Geekcraft: Step-by-Step Instructions for 25 Super-Cool Craft ProjectsVon EverandWorld of Geekcraft: Step-by-Step Instructions for 25 Super-Cool Craft ProjectsBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (13)

- The LEGO Story: How a Little Toy Sparked the World's ImaginationVon EverandThe LEGO Story: How a Little Toy Sparked the World's ImaginationBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (14)

- Book of Glock: A Comprehensive Guide to America's Most Popular HandgunVon EverandBook of Glock: A Comprehensive Guide to America's Most Popular HandgunBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Gunsmithing Modern Firearms: A Gun Guy's Guide to Making Good Guns Even BetterVon EverandGunsmithing Modern Firearms: A Gun Guy's Guide to Making Good Guns Even BetterBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- A No Fluff Beginners Guide to Coin Collecting 2023 - 2024: A Simplified Guide to Identify and invest in Rare and Error CoinsVon EverandA No Fluff Beginners Guide to Coin Collecting 2023 - 2024: A Simplified Guide to Identify and invest in Rare and Error CoinsNoch keine Bewertungen